Abstract

Objective

We hypothesized second trimester serum cortisol would be higher in spontaneous preterm births compared to provider-initiated (previously termed ‘medically indicated’) preterm births.

Study design

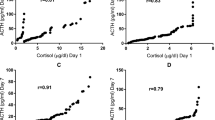

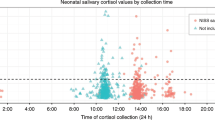

We used a nested case-control design with a sample of 993 women with live births. Cortisol was measured from serum samples collected as part of routine prenatal screening. We tested whether mean-adjusted cortisol fold-change differed by gestational age at delivery or preterm birth subtype using multivariable linear regression.

Result

An inverse association between cortisol and gestational age category (trend p = 0.09) was observed. Among deliveries prior to 37 weeks, the mean-adjusted cortisol fold-change values were highest for preterm premature rupture of the membranes (1.10), followed by premature labor (1.03) and provider-initiated preterm birth (1.01), although they did not differ statistically.

Conclusion

Cortisol continues to be of interest as a marker of future preterm birth. Augmentation with additional biomarkers should be explored.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Howson CP, Kinney MV, McDougall L, Lawn JE. Born toon soon: preterm birth matters. Reprod Health. 2013;10:S1–S1.

Kapoor A, Dunn E, Kostaki A, Andrews MH, Matthews SG. Fetal programming of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal function: prenatal stress and glucocorticoids. J Physiol. 2006;572:31–44.

Himes KP, Simhan HN. Plasma corticotropin-releasing hormone and cortisol concentrations and perceived stress among pregnant women with preterm and term birth. Am J Perinatol. 2011;28:443–8.

Hoffman MC, Mazzoni SE, Wagner BD, Laudenslager ML, Ross RG. Measures of maternal stress and mood in relation to preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:545–52.

Kramer MS, Lydon J, Goulet L, Kahn S, Dahhou M, Platt RW, et al. Maternal stress/distress, hormonal pathways and spontaneous preterm birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27:237–46.

Kramer MS, Lydon J, Seguin L, Goulet L, Kahn SR, McNamara H, et al. Stress pathways to spontaneous preterm birth: the role of stressors, psychological distress, and stress hormones. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1319–26.

Giurgescu C. Are maternal cortisol levels related to preterm birth? J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38:377–90.

Sandman CA, Glynn L, Schetter CD, Wadhwa P, Garite T,Chicz-DeMet A, et al. Elevated maternal cortisol early in pregnancy predicts third trimester levels of placental corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH): priming the placental clock. Peptides. 2006;27:1457–63.

Burton GJ, Jaunaiux E. Maternal vascularisation of the human placenta: does the embryo develop in a hypoxic environment? Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2001;29:503–8.

Schulte HM, Weisner D, Allolio B. The Corticotrophin releasing hormone test in late pregnancy: lack of adrenocorticotrophin and cortisol response. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1990;33:99–106.

Glover V. Maternal depression, anxiety and stress during pregnancy and child outcome; what needs to be done. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:25–35.

O’Donnell K, O’Connor TG, Glover V. Prenatal stress and neurodevelopment of the child: Focus on the HPA axis and role of the placenta. Dev Neurosci. 2009;31:285–92.

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84.

Reddy UM, Ko C-W, Raju TNK, Willinger M. Delivery indications at late-preterm gestations and infant mortality rates in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:234–40.

Xu Y, Romero R, Miller D, Silva P, Panaitescu B, Theis KR et al. Innate lymphoid cells at the human maternal-fetal interface in spontaneous preterm labor. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2018; e12820.

Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science. 2014;345:760–5.

Keelan JA. Intrauterine inflammatory activation, functional progesterone withdrawal, and the timing of term and preterm birth. J Reprod Immunol. 2018;125:89–99.

Wadhwa PD, Culhane JF, Rauh V, Barve SS, Hogan V, Sandman CA, et al. Stress, infection and preterm birth: a biobehavioural perspective. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:17–29.

Coussons-Read ME, Okun ML, Nettles CD. Psychosocial stress increases inflammatory markers and alters cytokine production across pregnancy. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:343–50.

Vrachnis N, Karavolos S, Iliodromiti Z, Sifakis S, Siristatidis C, Mastorakos G, et al. Impact of mediators present in amniotic fluid on preterm labour. Vivo (Brooklyn). 2012;26:799–812.

DeSantis AS, DiezRoux AV, Hajat A, Aiello AE, Golden SH, Jenny NS, et al. Associations of salivary cortisol levels with inflammatory markers: The multi-ethnic study of Atherosclerosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:1009–18.

Yeager MP, Pioli PA, Guyre PM. Cortisol exerts bi-phasic regulation of inflammation in humans. Dose-Response. 2011;9:332–47.

Menon R, Dunlop AL, Kramer MR, Fortunato SJ, Hogue CJ. An overview of racial disparities in preterm birth rates: caused by infection or inflammatory response? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:1325–31.

Sanchez-Vaznaugh EV, Braveman PA, Egerter S, Marchi KS, Heck K, Curtis M. Latina birth outcomes in California: not so paradoxical. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:1849–60.

Simon CD, Adam EK, Holl JL, Wolfe KA, Grobman WA, Borders AEB. Prenatal stress and the cortisol awakening response in African-American and Caucasian women in the third trimester of pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:2142–9.

Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL, Baer RJ, Blumenfeld YJ, Ryckman KK, O’Brodovich HM, Gould JB, et al. Maternal characteristics and mid-pregnancy serum biomarkers as risk factors for subtypes of preterm birth. BJOG. 2015;122:1484–93.

Wallenstein M, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL, Yang W, Carmichael S, Stevenson D, Ryckman K, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers and spontaneous preterm birth among obese women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:3317–22.

Califonia Biobank Program. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CFH/DGDS/Pages/cbp/default.aspx. accessed December 5, 2017

Ryckman KK, Jelliffe-pawlowski L, Bedell B, Holt T, Bell LN, Shaw GM et al. Global metabolic profiling implicates altered fatty acid and amino acid metabolism in preterm birth. unpublished. 2017.

Spong C. Defining ‘term’ pregnancy: recommendations from the defining ‘term’ pregnancy workgroup. JAMA. 2013;309:2445–6.

Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Lackritz EM. Epidemiology of late and moderate preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17:120–5.

Behrman R, Butler A, (Eds.) Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington (DC): National Academic Press; 2007 https://doi.org/10.17226/11622.

Chaim W, Mazor M. The relationship between hormones and human parturition. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1998;262:43–51.

Fowden AL, Forhead aJ, Coan PM, Burton GJ. The placenta and intrauterine programming. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:439–50.

Clarke Ka, Ward JW, Forhead aJ, Giussani Da, Fowden aL. Regulation of 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 activity in ovine placenta by fetal cortisol. J Endocrinol. 2002;172:527–34.

Seth S, Lewis AJ, Saffery R, Lappas M, Galbally M. Maternal prenatal mental health and placental 11β-HSD2 gene expression: initial findings from the mercy pregnancy and emotional wellbeing study. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:27482–96.

Shang Y, Jia Y, Sun Q, Shi W, Li R, Wang S, et al. Sexually dimorphic effects of maternal dietary protein restriction on fetal growth and placental expression of 11β-HSD2 in the pig. Anim Reprod Sci. 2015;160:40–8.

Mikelson C, Kovach MJ, Troisi J, Symes S, Adair D, Miller RK, et al. Placental 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 expression: correlations with birth weight and placental metal concentrations. Placenta. 2015;36:1212–7.

Staneva A, Bogossian F, Pritchard M, Wittkowski A. The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: a systematic review. Women Birth. 2015;28:179–93.

Feller S, Vigl M, Bergmann MM, Boeing H, Kirschbaum C, Stalder T. Predictors of hair cortisol concentrations in older adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;39:132–40.

Melin EO,Thunander M,Landin-Olsson M,Hillman M,Thulesius HO, Depression, smoking, physical inactivity and season independently associated with midnight salivary cortisol in type 1 diabetes. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:75.

Incollingo Rodriguez AC, Epel ES, White ML, Standen EC, Seckl JR, Tomiyama AJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation and cortisol activity in obesity: a systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:301–18.

2017 Premature Birth Report Cards. March of Dimes. 2017: 1–4. https://www.marchofdimes.org/mission/prematurity-reportcard.aspx, accessed November 8, 2017

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH/NHLBI grants (RC2 HL101748, RO1 HD-57192, and R01 HD-52953), the Bill and Melinda Gates Millennium grants (OPP52256 and RSDP 5K12 HD-00849-23), March of Dimes grants (6-FY11-261 and FY10-180), and the California Preterm Birth Initiative at the UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital funded by Marc and Lynne Benioff. Data from the California Prenatal Screening Program were obtained through the California Biobank Program (Screening Information System request no. 476). Data were obtained with an agreement that the California Department of Public Health is not responsible for the results or conclusions drawn by the authors of this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bandoli, G., Jelliffe-Pawlowski, L.L., Feuer, S.K. et al. Second trimester serum cortisol and preterm birth: an analysis by timing and subtype. J Perinatol 38, 973–981 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-018-0128-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-018-0128-5

This article is cited by

-

Associations between maternal awakening salivary cortisol levels in mid-pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2022)

-

Paternal violent criminality and preterm birth: a Swedish national cohort study

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2020)