Abstract

Background

The Brief Intervention for Weight Loss Trial enrolled 1882 consecutively attending primary care patients who were obese and participants were randomised to physicians opportunistically endorsing, offering, and facilitating a referral to a weight loss programme (support) or recommending weight loss (advice). After one year, the support group lost 1.4 kg more (95%CI 0.9 to 2.0): 2.4 kg versus 1.0 kg. We use a cohort simulation to predict effects on disease incidence, quality of life, and healthcare costs over 20 years.

Methods

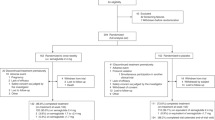

Randomly sampling from the trial population, we created a virtual cohort of 20 million adults and assigned baseline morbidity. We applied the weight loss observed in the trial and assumed weight regain over four years. Using epidemiological data, we assigned the incidence of 12 weight-related diseases depending on baseline disease status, age, gender, body mass index. From a healthcare perspective, we calculated the quality adjusted life years (QALYs) accruing and calculated the incremental difference between trial arms in costs expended in delivering the intervention and healthcare costs accruing. We discounted future costs and benefits at 1.5% over 20 years.

Results

Compared with advice, the support intervention reduced the cumulative incidence of weight-related disease by 722/100,000 people, 0.33% of all weight-related disease. The incremental cost of support over advice was £2.01million/100,000. However, the support intervention reduced health service costs by £5.86 million/100,000 leading to a net saving of £3.85 million/100,000. The support intervention produced 992 QALYs/100,000 people relative to advice.

Conclusions

A brief intervention in which physicians opportunistically endorse, offer, and facilitate a referral to a behavioural weight management service to patients with a BMI of at least 30 kg/m2 reduces healthcare costs and improves health more than advising weight loss.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aveyard P, Lewis A, Tearne S, Hood K, Christian-Brown A, Adab P, et al. Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2492–500.

Lewis A, Jolly K, Adab P, Daley A, Farley A, Jebb S, et al. A brief intervention for weight management in primary care: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:393.

Zomer E, Gurusamy K, Leach R, Trimmer C, Lobstein T, Morris S, et al. Interventions that cause weight loss and the impact on cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17:1001–11.

Dansinger ML, Tatsioni A, Wong JB, Chung M, Balk EM. Meta-analysis: the effect of dietary counseling for weight loss. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:41–50.

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinol. 2015;3:866–75.

McPherson K, Marsh T, Brown M. Foresight tackling obesities: Future choices – modelling future trends in obesity and the impact on health. Foresight tackling obesities future choices. 2007. Government Office for Science. Department of Innovation Universities and Skills. https://www.dius.gov.ukDIUS/PUB8603/2K/10/17/NP.

Webber L, Divajeva D, Marsh T, McPherson K, Brown M, Galea G, et al. The future burden of obesity-related diseases in the 53 WHO European-Region countries and the impact of effective interventions: a modelling study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004787.

Hollingworth W, Hawkins J, Lawlor DA, Brown M, Marsh T, Kipping RR. Economic evaluation of lifestyle interventions to treat overweight or obesity in children. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012;36:559–66.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Weight management: lifestyle services for overweight or obese adults, 2014. Public health guideline (PH53) https://www.nice.org.ukguidance/ph53.

Ahern AL, Wheeler GM, Aveyard P, Boyland EJ, Halford JC, Mander AP, et al. Extended and standard duration weight-loss programme referrals for adults in primary care (WRAP): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2214–25.

Sullivan PW, Slejko JF, Sculpher MJ, Ghushchyan V. Catalogue of EQ-5D scores for the United Kingdom. Med Decis Mak. 2011;31:800–4.

National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance. 3rd ed. London: NICE; 2012.

National Health Service. 2012-13 programme budgeting PCT benchmarking tool, 2013. https://www.networks.nhs.uk/nhs-networks/health-investment-network/news/2012-13-programme-budgeting-data-is-now-available.

Kanavos P, van der Aardweg S, Schurer W. Diabetes expenditure, burden of disease and management in 5 EU countries. London: LSE; 2012.

Vemer P, Mölken Rutten-van. MPMH. Largely ignored: the impact of the threshold value for a QALY on the importance of a transferability factor. Eur J Health Econ. 2011;12:397.

Brown M, Marsh T, Retat L, Fordham R, Suhrcke M, Turner D, et al. Managing overweight and obesity among adults. report on economic modelling and cost consequence analysis. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2013.

Hinde S, Bojke L, Richardson G, Retat L, Webber L. The cost-effectiveness of population Health Checks: have the NHS Health Checks been unfairly maligned? J Public Health. 2017;25:425–31.

Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet. 2011;378:815–25.

Booth HP, Prevost AT, Gulliford MC. Access to weight reduction interventions for overweight and obese patients in UK primary care: population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006642.

Noordman J, Verhaak P, van Dulmen S. Discussing patient’s lifestyle choices in the consulting room: analysis of GP-patient consultations between 1975 and 2008. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:87.

Prospective Studies C, Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1083–96.

Ramsay SE, Arianayagam DS, Whincup PH, Lennon LT, Cryer J, Papacosta AO, et al. Cardiovascular risk profile and frailty in a population-based study of older British men. Heart. 2015;101:616–22.

Ma C, Avenell A, Bolland M, Hudson J, Stewart F, Robertson C, et al. Effects of weight loss interventions for adults who are obese on mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2017;359:j4849.

Lee RH. Future costs in cost effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ. 2008;27:809–18.

Garber AM, Phelps CE. Economic foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis. J Health Econ. 1997;16:1–31.

Lindström J, Peltonen M, Eriksson JG, Ilanne-Parikka P, Aunola S, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, et al. Improved lifestyle and decreased diabetes risk over 13 years: long-term follow-up of the randomised Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS). Diabetologia. 2013;56:284–93.

Jolly K, Lewis A, Beach J, Denley J, Adab P, Deeks JJ, et al. Comparison of range of commercial or primary care led weight reduction programmes with minimal intervention control for weight loss in obesity: Lighten Up randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2011;343:d6500.

Hartmann-Boyce J, Johns DJ, Jebb SA, Summerbell C, Aveyard P. Behavioural Weight Management Review G. Behavioural weight management programmes for adults assessed by trials conducted in everyday contexts: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2014;15:920–32.

Hartmann-Boyce J, Jebb SA, Fletcher BR, Aveyard P. Self-help for weight loss in overweight and obese adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e43–e57.

Fleming DM. Morbidity registration and the fourth general practice morbidity survey in England and Wales. Scand J Prim Health Care Suppl. 1993;2:37–41.

Hobbs FD, Bankhead C, Mukhtar T, Stevens S, Perera-Salazar R, Holt T, et al. Clinical workload in UK primary care: a retrospective analysis of 100 million consultations in England, 2007-14. Lancet. 2016;387:2323–30.

Smolina K, Wright FL, Rayner M, Goldacre MJ. Determinants of the decline in mortality from acute myocardial infarction in England between 2002 and 2010: linked national database study. Corrected data on incidence and mortality in 2013. BMJ. 2012;344:d8059.

British Heart Foundation. Cardiovascular disease statistics 2014 2015. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/publications/statistics/cardiovascular-disease-statistics-2014 & https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/publications/statistics/cvd-stats-2015.

Office for National Statistics. Deaths registrations summary statistics, England and Wales. 2014. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/deathregistrationssummarytablesenglandandwalesreferencetables.

World Obesity Federation. Relative risk assessments IASO; prepared for DYNAMO-HIA project. In. https://www.dynamo-hia.eu/sites/default/files/2018-04/BMI_WP7-datareport_20100317.pdf.

Laires PA, Ejzykowicz F, Hsu TY, Ambegaonkar B, Davies G. Cost-effectiveness of adding ezetimibe to atorvastatin vs switching to rosuvastatin therapy in Portugal. J Med Econ. 2015;18:565–72.

British Heart Foundation. Stroke statistics 2009. 2009. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/publications/statistics/stroke-statistics-2009.

Rivero-Arias O, Ouellet M, Gray A, Wolstenholme J, Rothwell PM, Luengo-Fernandez R. Mapping the modified Rankin scale (mRS) measurement into the generic EuroQol (EQ-5D) health outcome. Med Decis Mak. 2010;30:341–54.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Health survey for England 2012. 2012.

Polder JJ, Bonneux L, Meerding WJ, van der Maas PJ. Age-specific increases in health care costs. Eur J Public Health. 2002;12:57–62.

International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes atlas, 2014.

Arthritis Research UK. Musculoskeletal calculator. 2016.

Zheng H, Chen C. Body mass index and risk of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007568.

Conner-Spady BL, Marshall DA, Bohm E, Dunbar MJ, Loucks L, Al Khudairy A, et al. Reliability and validity of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L in patients with osteoarthritis referred for hip and knee replacement. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:1775–84.

Oxford Economics. The economic cost of arthritis for the UK economy - Final report. 2010. https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/my-oxford/projects/128882.

Cancer Research UK. Statistics by cancer type - average number of new cases per year and age-specific incidence rates per 100,000 Population, UK 2011–3. 2016. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/incidence/age.

Cancer Research UK. Statistics by cancer type - average number of deaths per year and age-specific mortality rates, UK, 2010-2. In, 2016. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/mortality/age.

Office for National Statistics. Cancer survival in England- adults diagnosed: 2009 to 2013, followed up to 2014. 2015. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/cancersurvivalinenglandadultsdiagnosed/2009to2013followedupto2014.

Office for National Statistics. Cancer Survival in England: 10 year survival rates adults diagnosed between 2010-1 and followed up to 2012, 2013. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/datasets/cancersurvivalratescancersurvivalinenglandadultsdiagnosed.

Aune D, Navarro Rosenblatt DA, Chan DSM, Abar L, Vingeliene S, Vieira AR, et al. Anthropometric factors and ovarian cancer risk: A systematic review and nonlinear dose‐response meta‐analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1888–98.

World Cancer Research Fund. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. 2007. https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer.

Romanus D, Kindler HL, Archer L, Basch E, Niedzwiecki D, Weeks J, et al. Does health-related quality of life improve for advanced pancreatic cancer patients who respond to gemcitabine? Analysis of a randomized phase III trial of the cancer and leukemia group B (CALGB 80303). J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;43:205–17.

Curtis L, Burns A. Unit costs of health and social care 2015. personal social services research unit, Canterbury: University of Kent; 2015.

Acknowledgements

The trial was funded by the National Prevention Research Initiative of the UK, administered by the MRC. The funding partners are Alzheimer’s Research UK, Alzheimer’s Society, Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health Directorate, Department of Health, Diabetes UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Health and Social Care Research Division, Public Health Agency, Northern Ireland, Medical Research Council, Stroke Association, Wellcome Trust, Welsh Government, and World Cancer Research Fund. The weight loss programmes we used were provided by Slimming World and Rosemary Conley Health and Fitness Clubs. These are widely available through the English NHS at no cost to the patient and for which these organisations receive a fee. In this trial these 12-week programs were donated to the NHS by both these organisations and we are very grateful to them for this. Neither organisation had input into the protocol, the data analysis, or were involved in the decision to publish the findings. The investigators have no financial relationships with these companies. KJ is part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC). Paul Aveyard and Susan Jebb are NIHR senior investigators and funded by the Oxford NIHR Biomedical Research Centre and CLAHRC. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health. SJ and PA are investigators on an investigator-initiated randomised trial of Cambridge Weight Plan and funded by a research grant to the University of Oxford. None of the investigators have received personal financial payments from any of these research relationships.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Retat, L., Pimpin, L., Webber, L. et al. Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: cost-effectiveness analysis in the BWeL trial. Int J Obes 43, 2066–2075 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0295-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0295-7

This article is cited by

-

Cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgery and non-surgical weight management programmes for adults with severe obesity: a decision analysis model

International Journal of Obesity (2021)

-

Weight assessment and the provision of weight management advice in primary care: a cross-sectional survey of self-reported practice among general practitioners and practice nurses in the United Kingdom

BMC Family Practice (2020)