Abstract

Recent advances in the understating of tumor immunology suggest that cancer immunotherapy is an effective treatment against various types of cancer. In particular, the remarkable successes of immune checkpoint-blocking antibodies in clinical settings have encouraged researchers to focus on developing other various immunologic strategies to combat cancer. However, such immunotherapies still face difficulties in controlling malignancy in many patients due to the heterogeneity of both tumors and individual patients. Here, we discuss how tumor-intrinsic cues, tumor environmental metabolites, and host-derived immune cells might impact the efficacy and resistance often seen during immune checkpoint blockade treatment. Furthermore, we introduce biomarkers identified from human and mouse models that predict clinical benefits for immune checkpoint blockers in cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historical records suggest that scientists have sought for over a century to activate and harness the body’s immune response in order to eradicate cancerous cells. It was first attempted in 1891, based on observations regarding the remissions of tumors after surgery in patients with infections1. To reproduce this phenomenon, William Coley attempted to inject inactivated or live Streptococcus pyogenes organisms into a patient with neck and tonsil cancer. Due to bacterial-induced inflammation, the patient developed a high fever; however, the tumor burden regressed. Oncologists at the time assumed that the bystander killing effect of inflammation reduced tumor size but disregarded Coley’s approach due to the lack of exact scientific proof and risks concerning the inoculation of infectious organisms. By the 1990s, however, the development of mouse systems of pure genetic background enabled researchers to revisit the cancer immune-surveillance theory and to elucidate how the tumor environment is sculpted by the immune system to eventually either be eliminated or ignored2,3,4.

Despite decades of bench-side research, it has only been several years since immunotherapy was allowed to move into the mainstream of cancer therapeutics in the clinic. Recent approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of ipilimumab, a cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) blocking antibody, for the treatment of melanoma5 has encouraged the placement of immunotherapy at the forefront of cancer treatment. CTLA-4 was first known as a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily induced by activated T cells to transmit self-inhibitory signals6. Subsequently, antibodies blocking the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1):PD-L1 pathway, now referred to as an immune checkpoint, along with CTLA-4, have demonstrated promising effects in patients for treating more than ten types of cancers, including non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) and renal cell carcinoma (RCC)7,8,9. Soon after, additional immune checkpoints were discovered, leading researchers to focus on the development of new-generations of immune checkpoint blockers. However, numerous populations of cancer patients remain uncured by these treatments, necessitating novel therapeutic solutions for non-responders.

In this review, we summarize the current status of immune checkpoint blockers in clinical settings and discuss the efficacy of applying several immune checkpoint-blocking antibodies in combination. We also introduce comprehensive clinical studies that identify biomarkers for distinguishing responsive from non-responsive or resistant cancers in patients treated with immune checkpoint blockers. We also discuss how regulating tumor-autonomous factors is critical for immuno-resistance and how using agents that control tumor-extrinsic factors influence anti-tumor immunity.

Immune checkpoint blockers (ICBs)

Immune checkpoints consist of various inhibitory pathways that act as homeostatic regulators of the immune system and are crucial for maintaining central/peripheral tolerance as well as reducing excessive systemic inflammation in the body10. In the tumor environment, however, tumors hijack these inhibitory mechanisms to avoid anti-tumor immune responses.

CTLA-4

The first clinical development of a CTLA-4-blocking antibody, ipilimumab, proved that immune checkpoints would be attractive targets for cancer therapy. CTLA-4 is known to be expressed by activated T cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs). Together with TCR-mediated signal 1, CD28 ligation with CD80/86 on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) delivers signal 2 to trigger T-cell survival and expansion by inducing interleukin (IL)-2 production11. CTLA-4 binds CD80 and CD86 with a far higher affinity than CD28, thereby outcompeting for the same ligands and inhibiting TCR signaling6,12. As a result, CTLA-4-blocking antibodies augment the binding of CD80/86 to CD28 rather than to CTLA-4 and also deplete Tregs in the tumor environment that consistently express CTLA-4 (Fig. 1a)13,14.

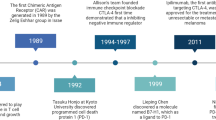

a Schematic of the mechanism of action of ICB agents. b Timeline highlights of ICB therapy development from its inspection of T-cell activation mechanisms, including the discovery of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1, to recent clinical trials that are either already approved or are expected to be approved by the FDA

Once the CTLA-4 signal was shown to restrict the activity of T cells, agents that shut down this signaling molecule became candidates for combination treatment with existing cancer therapeutics15,16. In 2010, a surprising result came from a phase III clinical study of the GP100 peptide vaccine with an anti-CTLA-4 mAb, ipilimumab (MDX-010, Bristol-Myers Squibb). Unexpectedly, only ipilimumab-treated patients showed prolonged survival compared with patients treated with the peptide vaccine alone or with the vaccine combined with ipilimumab17. These clinical outcomes allowed the FDA to approve ipilimumab for the treatment of melanoma in humans and led to additional approvals for the treatment of RCC18. Additionally, phase II and III studies showed that anti-CTLA-4 blockade treatment in advanced-melanoma patients resulted in a 22% 3-year survival rate and durable responses extending beyond 10 years19.

PD-1 and PD-L1

PD-1, another member of the inhibitory receptor family, is also expressed on T cells during TCR stimulation. The expression of its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, is regulated by inflammatory cytokines. While PD-L2 is exclusively induced on APCs, PD-L1 is expressed on tumor cells, epithelial cells, and immune cells. These molecules inhibit TCR downstream signaling when ligated with PD-120,21 (Fig. 1a). Two different PD-1-blocking antibodies, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, are currently the most promising qualifiers expected to provide significant clinical benefit. Several publications showed that patients with advanced melanoma, NSCLC and RCC experienced objective responses following PD-1 blockade22,23,24. These results encouraged the FDA to approve those antibodies for such indications. The success of PD-1-blocking antibodies in clinical settings promoted the development of PD-L1 blockers, such as atezolizumab, for the treatment of bladder cancer patients25. Together with PD-1, PD-L1 binds to CD80 expressed on T-cell surfaces26. Due to the complicated interaction, PD-L1 still can inhibit T-cell responses during PD-1 blockade. Furthermore, PD-L1 expression has been shown to increase when tumor cells are exposed to interferon (IFN)-γ during therapy, indicating that PD-L1 blockade might have an advantage over the PD-1-blocking antibody in some cases27,28.

As to the novel mechanistic explanation for the immune responses that lead to anti-PD-1 blockade-mediated tumor rejection, recent studies have shown that anti-PD-1 therapy leads to a dynamic expansion and proliferation of PD-1+ (exhausted-like) CD8 T cells in the PBMCs of melanoma and lung cancer patients29,30. Despite such clinical data, it is still yet unknown whether the expansion of ICB-responsive exhausted-like CD8 T cells is driven by the direct therapeutic engagement of peripheral or tumor-infiltrating populations or what functionally distinguishes the ICB-responsive from the non-responsive exhausted-like CD8 T cells. However, chronic viral infection models suggest that it is possible that expansion of specific tumor-infiltrating PD-1+ CD8 T-cell subsets in response to ICB results from the selective expansion of a distinct progenitor CD8 T-cell population in the secondary lymphoid organs31.

Other inhibitory receptors or combination therapy

Recent studies have suggested that several proteins expressed on T cells regulate exhaustion. Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) induced on activated T cells and Tregs binds to MHC class II or galectin-3, which transduces an inhibitory signal in T cells or enhances the suppressive activity of Tregs32,33. Agents blocking LAG-3 are being tested in clinical trials against multiple cancers.

T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing 3 (TIM-3; HAVCR2) is another cell surface molecule involved in T-cell exhaustion34. It was first demonstrated that TIM-3 controls T-cell unresponsiveness in chronic inflammation. Upon interaction with galectin-9 or other undefined ligands, TIM-3-expressing T cells undergo apoptosis and lose effector functions35. Further analysis showed that TIM-3 expression was upregulated in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in melanoma and NSCLC patients36,37.

T-cell immune receptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT) is also implicated in the inhibition of T-cell activation. TIGIT expression is tightly regulated in lymphocytes, especially in Tregs and CD8 T cells38, and is a phenotypic marker of inert CD8 T cells or mediates Treg suppression of other effector cells39,40. As such, blockade of TIGIT might be considered as an attractive target in conjunction with the CTLA-4/PD-1 pathways. The current status of the development and approval of immunotherapeutic agents is listed in Table 1.

To improve therapeutic efficacy, a number of preclinical and clinical studies have been conducted to examine if combination treatment of immune checkpoint blockers with conventional treatments, such as chemotherapies, targeted therapies, radiation therapies, and other immunotherapeutic agents, could improve outcomes. So far, the most favorable prognosis has been the combination of CTLA-4 and PD-1-blocking antibodies. In the first clinical study performed to determine the antibody combination dose, objective response rates were exhibited in over 40% of patients across all doses41. Notably, this study demonstrated that 28% of patients with clinical benefits showed 80% or greater tumor regression24. In a sequential phase II study, 61% of the patients who received the combination therapy exhibited objective responses compared to the 11% of those treated with ipilimumab alone42. Although not statically significant in comparison with the PD-1 single blockade group (nivolumab), the progression-free survival (PFS) rate was clearly prolonged in the combination group compared to that of either monotherapy group (2.9%, 6.9%, and 11.5% for ipilimumab, nivolumab, and combination therapy, respectively)43,44. Up-to-date clinically tested combination therapies and ICB development time-lines are summarized in Table 2 and Fig. 1b, respectively17,42,45,46,47.

Clinical prognosis indicators for immune checkpoint blockers: responder or non-responder?

Despite the remarkable success of ICBs in improving objective response rates in a subset of patients, it has been demonstrated that only ≤ 20–30% of tumor patients with NSCLC, RCC, and melanoma benefited from CTLA-4 or PD-1 blockade17,23,48,49,50. This unresponsiveness to ICBs can be identified in two types of patients: patients who did not respond at all (primary resistance), and patients who relapsed after a partial response to ICBs (acquired resistance)51. These non-responder patients endure high treatment costs and toxicities with little benefit from the treatments. To sustain the success that ICBs have achieved in the treatment of various tumors in clinical settings, specific prognostic indicators should be identified to predict whether a patient would be rescued by ICB treatment (Fig. 2).

Several longitudinal analyses on genomic and immunologic signatures in biopsies (tissue or blood) of tumor patients pre- or post-ICB treatment suggest novel biomarkers for discriminating responders and non-responders. If patients are predicted to be a non-responder before or after ICB treatment, clinicians can, on an individual basis, determine whether additional therapeutic medications should be applied to resolve resistance associated with poor prognosis

Cellular composition/characteristics of the tumor environment

Initially, PD-L1 expression in the tumor environment seemed to be positively correlated with response to PD-1/PD-L1-blocking antibodies, but several exceptions have led to the recognition of PD-L1 as an imperfect marker. However, several groups have endeavored to identify robust biomarkers for the purpose of discriminating responders from non-responders through genomic and immunologic analyses from biopsies before or after treatment. In a study for pembrolizumab in patients with advanced melanoma, CD8 T-cell density was analyzed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in some tumor compartments52. When analyzing pre-treatment samples, patients with a good response had higher CD8 T-cell density in the invasive tumor margin compared with specimens from patients with progressive disease. Moreover, there was a significant correlation between the proximity of PD-1/PD-L1 expressing cells and favorable prognosis after therapy, indicating that physical accessibility between PD-1+, possibly CD8 T cells, and PD-L1+ cells would be the pre-requisite for an effective PD-1 blockade. Based on these observations, a predictive model for a clinical response was established. To test this model, pre-treatment specimens from 15 patients treated with pembrolizumab were blindly examined. Consequently, 9 out of 9 patients who experienced a favorable response and 4 out of 5 patients with progressive disease were accurately predicted, while one patient with stable disease was predicted to show a response to the therapy52. To identify robust predictors further, an in-depth longitudinal analysis for tumor samples was performed53. This study cohort consisted of 53 metastatic melanoma patients initially treated with ipilimumab, followed by a treatment of pembrolizumab for non-responders. Specimens were obtained before ipilimumab treatment, while on-treatment, and after a clinical response was evaluated (response vs. progression). Non-responders were treated with pembrolizumab, and biopsies were obtained at early and late stages of treatment. Among those samples, analysis of biopsies collected immediately after CTLA-4 or PD-1 blockade treatment provided highly correlated predictors for response rates. In an immunological assay, the density of CD8+, CD4+, CD3+CD45RO+ PD-1+ or PD-L1+ cells was higher in responders compared to non-responders. The proximity between CD68+ myeloid cells and CD8+ T cells was also higher in responders, though not significantly. In addition, a recent study has demonstrated that peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) immuno-profiling could predict response rates in melanoma patients treated with nivolumab or pembrolizumab. Using high-dimensional single-cell mass cytometry, the authors searched for differential signatures in PBMCs from responders vs. non-responders54. Among alterations, the increase in classical monocyte (CD14+CD16−CD33+HLA-DR+) frequency was the most prominent in responders, indicating that biomarkers from blood sample collections, rather than those from invasive tumor samples, can be used in clinical practice (Fig. 2).

Genomic/transcriptomic analysis reveals the difference in responder vs. non-responder patients

Given that the magnificent efficacy of immunotherapy was demonstrated in human studies, cytotoxic T cells work properly when they recognize antigen loaded onto MHC molecules on the surface of tumor cells. Because T cells are selected to maintain central tolerance in the thymus, these antigens would be the mutated forms of self-antigens, so-called neoantigens, created by tumor-specific chromosomal alterations and viral genomic substances. In this context, the efficacy of ICBs has been markedly outstanding in patients with highly mutated tumor burdens55. In 2014, whole-exome sequencing analysis on tumor samples from ipilimumab or tremelimumab-treated patients identified that the mutational load was directly correlated with a clinical benefit in advanced-melanoma patients56. Of note, the neoantigen landscape was also elucidated in patients with a strong response, and the peptides derived from these neoantigens activated T cells from patients ex vivo. Furthermore, a similar tendency in the circumstances of PD-1 blockade was identified. NSCLC patients treated with pembrolizumab were analyzed for tumor DNA sequencing57. The patients with significantly enhanced clinical efficacy were imprinted with an elevated nonsynonymous mutation load. Among them, the signatures related to smoking-induced mutation, neoantigen burdens, and DNA repair mutation were linked to a favorable clinical efficacy.

The genetic alteration in tumor cells has been attributed to defects in the DNA-related machinery. In particular, mutations in mismatch repair (MMR) proteins significantly enhanced the error rate in tumor cells, which can result in abnormal DNA microsatellites58. This microsatellite instability (MSI) is associated with the response of ICBs. In a phase 2 clinical study for pembrolizumab-treated patients with progressive metastatic colorectal carcinoma, the rate of the objective response was higher in patients with mismatch repair-deficient tumors than in patients with mismatch repair-proficient tumors59. A total of 1782 somatic mutations were detected in tumors with a mismatch repair deficiency, while only 73 mutations were identified in mismatch repair-proficient tumors, and higher mutation loads were associated with longer progression-free survival. Furthermore, a study indicated that not only colorectal cancer but also 12 different types of tumors harboring MMR deficiency were sensitive to PD-1 blockade60. Interestingly, there are several patients with high mutation loads who do not respond to ICBs61,62. This might be the consequence of intratumor heterogeneity, as multiregional genetic analysis of tumors from metastatic RCC patients revealed that spatially separated tumors exhibited discordant somatic mutation patterns63. In NSCLC and melanoma patients, sensitivity to pembrolizumab and ipilimumab was apparent in patients with high neoantigen loads and low heterogeneity in their tumor64, indicating that tumor clonal variability should be considered as a biomarker for the ICBs-responder prediction (Fig. 2).

In addition, genes for T-cell activation, antigen presentation, IFN-γ-related subunits, cytolytic markers, among others, were upregulated in samples collected from responders while on-treatment65,66, suggesting that these characteristics could be utilized as indicators to predict response rates. In contrast, the expression of a few genes, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), was lower in responders in comparison with non-responders, arguing that the resistance mechanism could be a target for combination therapy, as other have suggested67,68. In a consecutive study, whole-exome sequencing was performed on the biopsies from the same cohort of metastatic melanoma patients treated with sequential ICBs to complement the previous study69. In patients resistant to single or double ICBs, there was a high burden of copy number loss in chromosomes in which various tumor suppressor genes (FOXO3, PRDM1, PTEN, FAS, etc.) were located. Although more efforts are needed to expand the cohort size and to broaden these criteria, this study provides an important guide on how to manage the ICB regimen. The inspection of biopsies obtained at each time point provides several mechanisms by which the efficacy of ICBs is restricted (Fig. 2). Regulating those inhibitory circuits with serial ICB treatment could relieve patients of clinical resistance, which we discuss below.

The intestinal microbiome composition

Several studies from independent groups have shown that gut microbiota is required for the therapeutic effects of ICBs. These experiments conducted in mice have shown that the intestinal microbial composition determines how they respond to chemotherapy and ICBs, presumably mediated by the induction of DC maturation and Th1 responses in the tumor environment70,71. Experimental data supporting the hypothesis on the correlation between the colon microbiome and the clinical response to ICBs have been recently reported by multiple investigators72,73,74. For instance, three studies comparatively analyzed the bacterial families, species or diversity in stool by a metagenomic approach using whole-genome sequencing of 16S ribosomal RNA to investigate the microbiome of NSCLC, RCC72, and metastatic melanoma patients73,74 treated with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. These studies showed that patients with a high diversity of microorganisms and with specific species (e.g., Ruminococci, Bifidobacteria, and Enterococci) exhibited a favorable response to PD-1 blockade. To clarify the causality between ICBs efficacy and specific commensal species, germ-free mice were recolonized with the bacteria isolated from patient stool using fecal microbiota transplantation (FMS). Mice transplanted with stool from responders exhibited significant regression of tumor growth compared to those receiving stool from non-responders. In addition, microbiota composition in melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab was analyzed to distinguish specific bacteria associated with the efficacy and adverse effects, such as colitis75. This study revealed that the Faecalibacterium genus and other Firmicutes were responsible for the prolonged survival of patients and the occurrence of ICB-mediated-colitis. Although more investigations should be performed to confirm the relation between the microbiota and the clinical response, oncologists may need to consider the proper use of anti- or probiotics before and during ICB treatments to maximize the therapeutic effect (Fig. 2).

Resistance mechanisms to ICBs: future targets for combinatorial therapy

Many efforts have been made to gain mechanistic insights into the wide spectrum of patients who exhibit primary and/or acquired resistance to ICB and to find ways to maximize efficacy/coverage via combinational strategies. The approximately 430 and 390 on-going clinical studies investigating combination therapies with pembrolizumab and nivolumab, respectively, exemplify the sheer volume of efforts and resources invested in finding a more personalized, combinatory regimen. The reasons as to why some patients do not benefit from ICBs are largely associated with the defects in the context of T-cell behavior within the tumor environment. As such, many combination strategies target other biological pathways to better induce longer-lasting T-cell activity within the tumor environment. To properly induce tumor-specific T-cell responses, tumor antigens should be engulfed by professional antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells (DCs). Then, inflammatory stimuli activate DCs to migrate into adjacent lymph nodes in which T cells are educated by DCs presenting tumor antigens. The differentiation of tumor-specific T cells into effector T cells crucially contributes to tumor immunosurveillance. The interaction between CD28 and CD80/86 is indispensable for fully activating T-cell functions, while PD-1 and CTLA-4 blunt their ligation. Activated tumor-specific T cells differentiate into effector cells and then home to the tumor tissues attracted by chemokines and attack tumor cells expressing antigens loaded onto MHC molecules. Though ICBs potentiate T-cell activation, the other steps of immune-induced tumor-killing should be operated precisely to control tumor growth. In the following sections, we introduce the mechanisms of how both tumor-intrinsic and -extrinsic factors regulate immune activation cycles to restrict ICB efficacy.

Insights into primary resistance and non-responders to ICBs

Approximately 40 to 60% of melanoma patients treated with nivolumab, as well as over 70% of patients treated with ipilimumab, show primary resistance9,17,44,76,77. IPRES (Innate anti-PD-1 Resistance Signatures) describe a set of genes inherent to the patient that have been attributed to the primary mechanism of resistance to PD-1 blockade66. Comparative transcriptome analysis between melanoma and pancreatic patients who do and do not respond to PD-1 blockade revealed that non-responders showed an enrichment of genes associated with mesenchymal transition, wound healing, and angiogenesis66. In another aspect, other genomic indicators of poor immunogenicity, such as epigenetic downregulation of chemokines (lower T-cell recruitment), upregulation of endothelin receptors (higher tumor angiogenesis and survival), MHC downregulation and low neoantigen load (lower antigen exposure), and impaired DC function (lower antigen presentation), have been described and attributed to what is popularly termed “cold” tumor types78,79. Therapeutic interventions to improve the responsiveness of these “cold tumors” to ICB are being investigated with various combinational therapies in clinical trials.

Tumor-intrinsic factors related to resistance

As mentioned above, tumors with higher initial mutational burdens appeared to be positively correlated with therapeutic outcomes. However, the mutations in tumor cells do not always guarantee a favorable response to ICBs, as intratumoral heterogeneity and mutations that might be advantageous for immune-escape and survival can be another manifestation of the high mutational burden80. Loss of function mutations in Janus kinases JAK1 and JAK2 were observed in patients who exhibited no-response to pembrolizumab81 (Fig. 3). IFN-γ released by T cells post ICB was shown to sensitize tumor cells to activate these tyrosine kinases, after which tumor cells secrete T-cell-attracting chemokines and upregulate PD-L1 expression82. Similarly, melanoma patients with defects in the IFN-γ signaling pathway were resistant to ipilimumab treatment83. Tumor growth was also uncontrolled in mice bearing tumors with low IFNGR1 expression. Interestingly, chronic IFN-γ exposure rendered tumor cells resistant to ICBs through epigenome/transcriptome changes driven by JAK/STAT1, which is independent of PD-L1 expression84. CDK5, a cell-cycle regulator, has been shown to modulate and enhance PD-L1 expression in brain cancers in response to IFN-γ exposure85. Furthermore, CDK5 disruption resulted in enhanced expression of interferon response factors, indicating the tight epigenetic regulation that exists between the components of the cell-cycle and IFN signaling pathways. In this regard, IFN-γ release can be seen as a ‘‘double-edged sword’’, where acute IFN-γ is beneficial to the initial T-cell-mediated anti-tumor efforts (immune cell recruitment and activation) as well as in inducing MHC expression on tumor cells, whereas chronic IFN-γ exposure induces further mutations in tumor cells and leads to PD-L1 upregulation84.

Tumor-intrinsic resistance mainly originates from gain- and loss-of-mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, respectively. Mutations resulting in JAK1/2 malfunction break IFN-γ signaling pathways important for chemokine production and MHC I expression. PTEN loss mediates constitutive activation of PI3K to produce VEGF. The expression of MHC I and β2-microbulin (B2M) is also downregulated in patients with no-response to ICBs. Gain-of-function of β-catenin inhibits chemokine expression. In T cells, on the other hand, PD-1-blockade induces alternative TIM-3 (not significantly LAG-3 and CTLA-4) expression to limit activation. ATP metabolites participate in raising the tumor suppressive environment. Tumor suppressive myeloid cells and Treg cells express high levels of CD39 and CD73, degrading ATP and AMP into AMP and adenosine, respectively. Adenosine inhibits effector cell activation while promoting tumor cell proliferation. Adenosine deaminase (ADA) expressed on tumor cells degrades adenosine into inosine. Tumor-associated neutrophils promote tumor metastasis via VEGF/MMPs secretion while anti-tumor effector cells are subverted by IL-10/TGF-β. In addition, tumor-associated fibroblasts also secrete various metastatic/immunosuppressive mediators, which can exacerbate tumor progression

Oncogenic signals are also responsible for resistance to ICBs. In a subset of melanoma patients, active β-catenin levels were detected, along with the absence of T cells and CD103+ DCs in tumor tissues. β-catenin suppressed CCL4 secretion, which is important for the recruitment of T cells/DCs into the tumor bed (Fig. 3). The same molecular phenomenon has also resulted in resistance to PD-L1/CTLA-4 blocking antibodies in mouse experimental models86.

Gain-of-function mutations in BRAF, which drive MAPK pathway activation, have been demonstrated to potentially regulate the efficacy of immunotherapies. BRAF promoted immunosuppressive IL-1 secretion in the stromal cells of melanoma patients87. In addition, BRAF inhibited the expression of melanoma antigen, such as MART-1. BRAF or BRAF/MAPK inhibitor therapy enhanced anti-tumor immune responses in melanoma patients. However, an increase in PD-1 or PD-L1 was observed in patients with resistance to those inhibitors. In this case, additional ICB treatment may improve the therapeutic effect of BRAF/MAPK inhibitors88. Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) tumor suppressor loss has also been attributed to the resistance to PD-1 blockade in a mouse tumor model. The PI3K pathway was activated in the absence of PTEN, promoting immunosuppressive CCL2 and VEGF secretion. Tumor growth significantly regressed in the ICBs and PI3K inhibitor co-treatment group89 (Fig. 3). Concurrently, PTEN loss in a human melanoma dataset correlated with lower gene expression of IFN and reduced CD8+ T-cell infiltration89. In metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma, biallelic PTEN loss and changes in neoantigen expressions were correlated with resistance to pembrolizumab monotherapy90.

Alternatively, cancer cells may have defective β-2-microglobulin and HLA class I functions, leading to abnormal tumor antigen processing and presentation, respectively, facilitating escape from immune-surveillance91,92,93. Tumor cells also repressed the expression of Th1-type chemokines by epigenetic regulation, resulting in tumor cells restricting T cells from entering the tumor environment via negative regulation of proliferation, viability, and migration of tumor-specific T cells94,95.

Tumor-extrinsic factors related to resistance

It is now commonly accepted that cancer cells constitute suppressive networks with surrounding stromal cells and immune cells96. Typically, the tumor environment evades immune-mediated eradication through depleting essential nutrition or producing deleterious materials for immune cells. Cancer cells and myeloid cells express indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) to catalyze tryptophan into kynurenine, which induces T-cell dysfunction due to the deficiency of essential amino acid97. Furthermore, IDO enhances MDSCs and Treg cell recruitment into the tumor microenvironment98,99. IDO inhibitors have been shown to potentiate anti-tumor effects in combination with immune checkpoint blockers98,100 and are on the brink of being approved in clinical trials. Adenosine, also abundant in the tumor environment, inhibits effector functions of NK cells/CD8 T cells and induces suppressive M2 macrophage differentiation and myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) accumulation.

Adenosine also promotes the proliferation of cancer/blood vessel endothelial cells to broaden the tumoral niche101,102,103. Two ectonucleotidases, CD39 and CD73, have critical roles in generating adenosine. In inflammation, ATP released from cancer or immune cells is converted by CD39 into AMP, which CD73 then metabolizes into adenosine104 (Fig. 3). A recent study has demonstrated that a CD73-blocking antibody increases the anti-tumor effect of CTLA-4/PD-1 inhibition, suggesting that the combination of such treatments could be beneficial in clinical settings105.

Accumulating evidence indicates that MDSC infiltration in tumor tissues is strongly attributed to poor prognosis in ICB-treated patients due to the suppressive activity of the tumor-specific T-cell response106. In an analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of metastatic melanoma patients, MDSCs were higher in non-responders compared with responders during ipilimumab therapy, indicating discriminative biomarkers for the ICB response107. Recently, an attempt to overcome MDSC suppression by targeting the gamma isoform of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3Kγ) has been introduced108. A PI3Kγ inhibitor converted MDSCs into immunogenic myeloid cells, and subsequent tumor-specific CTL responses were enhanced in combination with ICBs. Other myeloid compartments, such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and neutrophils (TANs), have been shown to contribute to ICB resistance in distinct ways. TAMs have been primarily known to induce angiogenesis and enhance tumor survival via immunosuppressive factors and degradative proteins, thus facilitating therapeutic resistance109. Furthermore, recent in vivo imaging analysis revealed that PD-1- macrophages engulf anti-PD-1 antibodies that bind to PD-1+ CD8+ T cells in a FcγR-dependent manner to disrupt PD-1 efficacy110.

TANs are known to also release secretory factors, such as MMP2 and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), to induce ECM remodeling and recruit other immunosuppressive immune cells that aid in cancer immune-escape111. In a mouse model of KRAS-mutant lung tumor, pro-inflammatory IL-17A cytokine secretion has been shown to recruit neutrophils to the tumor sites, and anti-Ly6G depletion of neutrophils was found to be more effective than PD-1 blockade in treatment of the tumor112. Positive correlation between KRAS mutation and IL-17 levels was also found in lung cancer patients112. In an analysis of 720 advanced-melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab, a higher neutrophil baseline and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in the blood were found to be significantly associated with lower survival rates113. Taken together, TANs seem to contribute to resistance against ICBs.

TGF-β is another powerful negative regulator of effector T cells that is actively exploited by various compartments of the TME. A recent study of patients with metastatic bladder cancer who did not respond to atezolizumab therapy has shown that tumor-associated fibroblast- and collagen-rich extracellular matrices upregulate TGF-β expression, which could inhibit CD8+ T-cell infiltration into the tumor environment114. Combination of ICBs with TGF-β blockers proved to be synergistic in tumor mouse models

PD-1-blocking antibody therapy itself also induces the expression of inhibitory molecules in CD4/CD8 T cells to evade attack from immune cells. An increase in TIM-3 was found in T cells from patients with non-small cell lung cancer not responding to PD-1 blockade115. In a mouse model, therapeutic sensitivity to PD-1 blockade was restored in combination with a TIM-3-blocking antibody injection (Fig. 3). In addition, Treg infiltration into tumor tissues reduces the effector T-cell/Treg ratio, which is a negative indicator in tumor patients116. Treg depletion using Fc-optimized anti-CD25 antibody induced a synergistic and therapeutic effect with either nivolumab or pembrolizumab in an established tumor model117.

On the other hand, epigenetic studies have revealed that although ICBs do lead to transcriptional reprogramming within the exhausted T-cell pool, they induce minimal development in genes associated with memory T-cell generation118. Moreover, exhausted T cells displayed extensive changes in accessible chromatin, changes that were dissimilar to those of their effector T-cell counterparts119. Exhaustion-specific enhancers in exhausted T cells showed distinct motifs at RAR, T-bet, and Sox3 signature transcription factor binding sites119. The magnitude difference in the profile of regulatory regions between exhausted and functional CD8 T cells (44.48% of all chromatin-accessible regions differentially present) were greater than those observed in gene expression (only 9.75% differentially expressed genes), suggestive of a large rewiring of accessible chromatin networks associated with the exhaustion state. Thus, co-treatment with epigenetic and/or metabolic modulators has been proposed to overcome the inherent limitations of ICBs120.

Conclusion

The cancer field in the past few years has witnessed a great advancement in the comprehension of immune-surveillance in the tumor environment. Along the way, researchers have assumed that the regulation of immune checkpoint pathways might have an impact on anti-tumor immunity, thereby leading to the successful administration of CTLA-4/PD-1-blocking antibodies to treat many types of cancers. However, only a minority of patients’ tumors were reduced by this treatment due to tumor-intrinsic or -extrinsic resistance mechanisms, necessitating a clarification of genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, as well as cellular features linked with tumor response and resistance. Using novel molecular and diagnostic technologies, the resistance mechanisms should be fully addressed to offer custom-made therapies or optimal therapeutic combination to potentiate clinical responses for patients with a variety of tumors.

In other aspects, several attempts have been made to stimulate anti-tumor activity and/or to eliminate immune-threatening suppressors: the development of agonistic antibodies against costimulatory receptors (ICOS, GITR, 4-1BB, etc.)121,122, therapeutic vaccines that induce immune responses to tumor-specific antigen123,124, and agents that remove suppressive myeloid cells (MDSC, M2 macrophage, tolerogenic DC, etc.)125,126.

Importantly, recent breakthrough discoveries have demonstrated that some species of microbiota could manipulate anti-tumor immune responses to give rise to favorable clinical responses through the induction of DC maturation and a Th1 response, indicating that probiotics or antibiotics-mediated microbial rearrangement perhaps stimulate effective immune responses70,71. Considering the conditions of cellular, genomic, and microbial status within individual patients, strategies mentioned above will be integrated optimally to augment the therapeutic effect, which could, in the near future, save the lives of patients suffering from uncontrolled malignancies.

References

Coley, W. B. The treatment of malignant tumors by repeated inoculations of erysipelas. With a report of ten original cases. 1893. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 262, 3–11 (1991).

Little, C. C. A possible Mendelian explanation for a type of inheritance apparently non-Mendelian in nature. Science 40, 904–906 (1914).

Prehn, R. T. & Main, J. M. Immunity to methylcholanthrene-induced sarcomas. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 18, 769–778 (1957).

Schreiber, R. D., Old, L. J. & Smyth, M. J. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 331, 1565–1570 (2011).

Zhou, G. & Levitsky, H. Towards curative cancer immunotherapy: overcoming posttherapy tumor escape. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 124187 (2012).

Krummel, M. F. & Allison, J. P. CD28 and CTLA-4 have opposing effects on the response of T cells to stimulation. J. Exp. Med. 182, 459–465 (1995).

Rizvi, N. A. et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 16, 257–265 (2015).

Robert, C. et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 320–330 (2015).

Robert, C. et al. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2521–2532 (2015).

Dustin, M. L. The immunological synapse. Cancer Immunol. Res 2, 1023–1033 (2014).

Kapsenberg, M. L. Dendritic-cell control of pathogen-driven T-cell polarization. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 984–993 (2003).

Walunas, T. L. et al. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity 1, 405–413 (1994).

Selby, M. J. et al. Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies of IgG2a isotype enhance antitumor activity through reduction of intratumoral regulatory T cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 1, 32–42 (2013).

Simpson, T. R. et al. Fc-dependent depletion of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells co-defines the efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 therapy against melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 210, 1695–1710 (2013).

Gregor, P. D. et al. CTLA-4 blockade in combination with xenogeneic DNA vaccines enhances T-cell responses, tumor immunity and autoimmunity to self antigens in animal and cellular model systems. Vaccine 22, 1700–1708 (2004).

Quezada, S. A., Peggs, K. S., Curran, M. A. & Allison, J. P. CTLA4 blockade and GM-CSF combination immunotherapy alters the intratumor balance of effector and regulatory T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1935–1945 (2006).

Hodi, F. S. et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 711–723 (2010).

Royal, R. E. et al. Phase 2 trial of single agent Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Immunother. 33, 828–833 (2010).

Schadendorf, D. et al. Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 1889–1894 (2015).

Chemnitz, J. M., Parry, R. V., Nichols, K. E., June, C. H. & Riley, J. L. SHP-1 and SHP-2 associate with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif of programmed death 1 upon primary human T cell stimulation, but only receptor ligation prevents T cell activation. J. Immunol. 173, 945–954 (2004).

Parry, R. V. et al. CTLA-4 and PD-1 receptors inhibit T-cell activation by distinct mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9543–9553 (2005).

Garon, E. B. et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2018–2028 (2015).

Motzer, R. J. et al. Nivolumab for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results of a randomized phase II trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 1430–1437 (2015).

Topalian, S. L. et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 1020–1030 (2014).

Rosenberg, J. E. et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 387, 1909–1920 (2016).

Zou, W., Wolchok, J. D. & Chen, L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 328rv324 (2016).

Dong, H. et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat. Med. 8, 793–800 (2002).

Gao, Q. et al. Overexpression of PD-L1 significantly associates with tumor aggressiveness and postoperative recurrence in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 971–979 (2009).

Huang, A. C. et al. T-cell invigoration to tumour burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature 545, 60–65 (2017).

Kamphorst, A. O. et al. Proliferation of PD-1+CD8 T cells in peripheral blood after PD-1-targeted therapy in lung cancer patients. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 4993–4998 (2017).

Im, S. J. et al. Defining CD8+T cells that provide the proliferative burst after PD-1 therapy. Nature 537, 417–421 (2016).

Kouo, T. et al. Galectin-3 shapes antitumor immune responses by suppressing CD8+T cells via LAG-3 and inhibiting expansion of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol. Res 3, 412–423 (2015).

Wherry, E. J. et al. Molecular signature of CD8+T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity 27, 670–684 (2007).

Jin, H. T. et al. Cooperation of Tim-3 and PD-1 in CD8 T-cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14733–14738 (2010).

Sakuishi, K. et al. Targeting Tim-3 and PD-1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti-tumor immunity. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2187–2194 (2010).

Fourcade, J. et al. Upregulation of Tim-3 and PD-1 expression is associated with tumor antigen-specific CD8+T cell dysfunction in melanoma patients. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2175–2186 (2010).

Gao, X. et al. TIM-3 expression characterizes regulatory T cells in tumor tissues and is associated with lung cancer progression. PLoS ONE 7, e30676 (2012).

Yu, X. et al. The surface protein TIGIT suppresses T cell activation by promoting the generation of mature immunoregulatory dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 10, 48–57 (2009).

Johnston, R. J. et al. The immunoreceptor TIGIT regulates antitumor and antiviral CD8(+) T cell effector function. Cancer Cell 26, 923–937 (2014).

Lozano, E., Dominguez-Villar, M., Kuchroo, V. & Hafler, D. A. The TIGIT/CD226 axis regulates human T cell function. J. Immunol. 188, 3869–3875 (2012).

Wolchok, J. D. et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 122–133 (2013).

Postow, M. A. et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2006–2017 (2015).

Larkin, J., Hodi, F. S. & Wolchok, J. D. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1270–1271 (2015).

Larkin, J. et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 23–34 (2015).

Sznol, M. et al. Survival, response duration, and activity by BRAF mutation (MT) status of nivolumab (NIVO, anti-PD-1, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) and ipilimumab (IPI) concurrent therapy in advanced melanoma (MEL). J. Clin. Oncol. 32, LBA9003–LBA9003 (2014).

Hodi, F. S. et al. Ipilimumab plus sargramostim vs ipilimumab alone for treatment of metastatic melanoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 312, 1744–1753 (2014).

Melero, I. et al. Evolving synergistic combinations of targeted immunotherapies to combat cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 457–472 (2015).

Hamid, O. et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 134–144 (2013).

Gettinger, S. N. et al. Overall survival and long-term safety of nivolumab (anti-programmed death 1 antibody, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 2004–2012 (2015).

McDermott, D. F. et al. Atezolizumab, an anti-programmed death-ligand 1 antibody, in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Long-term safety, clinical activity, and immune correlates from a phase Ia study. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 833–842 (2016).

Sharma, P., Hu-Lieskovan, S., Wargo, J. A. & Ribas, A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell 168, 707–723 (2017).

Tumeh, P. C. et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515, 568–571 (2014).

Chen, P. L. et al. Analysis of immune signatures in longitudinal tumor samples yields insight into biomarkers of response and mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Discov. 6, 827–837 (2016).

Krieg, C. et al. High-dimensional single-cell analysis predicts response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 24, 144–153 (2018).

Schumacher, T. N. & Schreiber, R. D. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 348, 69–74 (2015).

Snyder, A. et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 2189–2199 (2014).

Rizvi, N. A. et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 348, 124–128 (2015).

Mandal, R. & Chan, T. A. Personalized oncology meets immunology: The path toward precision immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 6, 703–713 (2016).

Le, D. T. et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2509–2520 (2015).

Le, D. T. et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 357, 409–413 (2017).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500, 415–421 (2013).

Braun, D. A., Burke, K. P. & Van Allen, E. M. Genomic Approaches to understanding response and resistance to immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 5642–5650 (2016).

Gerlinger, M. et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 883–892 (2012).

McGranahan, N. et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 351, 1463–1469 (2016).

Van Allen, E. M. et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science 350, 207–211 (2015).

Hugo, W. et al. Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell 165, 35–44 (2016).

Voron, T. et al. VEGF-A modulates expression of inhibitory checkpoints on CD8+T cells in tumors. J. Exp. Med. 212, 139–148 (2015).

Ott, P. A., Hodi, F. S. & Buchbinder, E. I. Inhibition of immune checkpoints and vascular endothelial growth factor as combination therapy for metastatic melanoma: An overview of rationale, preclinical evidence, and initial clinical data. Front. Oncol. 5, 202 (2015).

Roh, W. et al. Integrated molecular analysis of tumor biopsies on sequential CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade reveals markers of response and resistance. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaah3560 (2017).

Sivan, A. et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science 350, 1084–1089 (2015).

Vetizou, M. et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science 350, 1079–1084 (2015).

Routy, B. et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 359, 91–97 (2018).

Gopalakrishnan, V. et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 359, 97–103 (2018).

Matson, V. et al. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science 359, 104–108 (2018).

Chaput, N. et al. Baseline gut microbiota predicts clinical response and colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Ann. Oncol. 28, 1368–1379 (2017).

Gide, T. N., Wilmott, J. S., Scolyer, R. A. & Long, G. V. Primary and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 1260–1270 (2018).

Robert, C. et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2517–2526 (2011).

Buckanovich, R. J. et al. Endothelin B receptor mediates the endothelial barrier to T cell homing to tumors and disables immune therapy. Nat. Med. 14, 28–36 (2008).

Lahav, R., Suva, M. L., Rimoldi, D., Patterson, P. H. & Stamenkovic, I. Endothelin receptor B inhibition triggers apoptosis and enhances angiogenesis in melanomas. Cancer Res. 64, 8945–8953 (2004).

Greaves, M. Evolutionary determinants of cancer. Cancer Discov. 5, 806–820 (2015).

Shin, D. S. et al. Primary resistance to PD-1 blockade mediated by JAK1/2 mutations. Cancer Discov. 7, 188–201 (2017).

Baumeister, S. H., Freeman, G. J., Dranoff, G. & Sharpe, A. H. Coinhibitory pathways in immunotherapy for cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 34, 539–573 (2016).

Gao, J. et al. Loss of IFN-gamma pathway genes in tumor cells as a mechanism of resistance to Anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Cell 167, 397–404 e399 (2016).

Benci, J. L. et al. Tumor interferon signaling regulates a multigenic resistance program to immune checkpoint blockade. Cell 167, 1540–1554 e1512 (2016).

Dorand, R. D. et al. Cdk5 disruption attenuates tumor PD-L1 expression and promotes antitumor immunity. Science 353, 399–403 (2016).

Spranger, S., Bao, R. & Gajewski, T. F. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature 523, 231–235 (2015).

Khalili, J. S. et al. Oncogenic BRAF(V600E) promotes stromal cell-mediated immunosuppression via induction of interleukin-1 in melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 5329–5340 (2012).

Frederick, D. T. et al. BRAF inhibition is associated with enhanced melanoma antigen expression and a more favorable tumor microenvironment in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 1225–1231 (2013).

Peng, W. et al. Loss of PTEN promotes resistance to T cell-mediated immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 6, 202–216 (2016).

George, S. et al. Loss of PTEN is associated with resistance to anti-PD-1 checkpoint blockade therapy in metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma. Immunity 46, 197–204 (2017).

Marincola, F. M., Jaffee, E. M., Hicklin, D. J. & Ferrone, S. Escape of human solid tumors from T-cell recognition: molecular mechanisms and functional significance. Adv. Immunol. 74, 181–273 (2000).

Sucker, A. et al. Genetic evolution of T-cell resistance in the course of melanoma progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 6593–6604 (2014).

Zaretsky, J. M. et al. Mutations associated with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 819–829 (2016).

Joyce, J. A. & Fearon, D. T. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science 348, 74–80 (2015).

Nagarsheth, N. et al. PRC2 epigenetically silences Th1-type chemokines to suppress effector T-cell trafficking in colon cancer. Cancer Res. 76, 275–282 (2016).

Hanahan, D. & Coussens, L. M. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 21, 309–322 (2012).

Platten, M., Wick, W. & Van den Eynde, B. J. Tryptophan catabolism in cancer: beyond IDO and tryptophan depletion. Cancer Res. 72, 5435–5440 (2012).

Holmgaard, R. B., Zamarin, D., Munn, D. H., Wolchok, J. D. & Allison, J. P. Indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase is a critical resistance mechanism in antitumor T cell immunotherapy targeting CTLA-4. J. Exp. Med. 210, 1389–1402 (2013).

Holmgaard, R. B. et al. Tumor-expressed IDO recruits and activates MDSCs in a treg-dependent manner. Cell Rep. 13, 412–424 (2015).

Spranger, S. et al. Mechanism of tumor rejection with doublets of CTLA-4, PD-1/PD-L1, or IDO blockade involves restored IL-2 production and proliferation of CD8(+) T cells directly within the tumor microenvironment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2, 3 (2014).

Young, A., Mittal, D., Stagg, J. & Smyth, M. J. Targeting cancer-derived adenosine: new therapeutic approaches. Cancer Discov. 4, 879–888 (2014).

Ma, D. F. et al. Hypoxia-inducible adenosine A2B receptor modulates proliferation of colon carcinoma cells. Hum. Pathol. 41, 1550–1557 (2010).

Weber, J. et al. Phase I/II study of metastatic melanoma patients treated with nivolumab who had progressed after ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol. Res 4, 345–353 (2016).

Yegutkin, G. G. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: Important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 673–694 (2008).

Allard, B., Pommey, S., Smyth, M. J. & Stagg, J. Targeting CD73 enhances the antitumor activity of anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 mAbs. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 5626–5635 (2013).

Diaz-Montero, C. M., Finke, J. & Montero, A. J. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer: therapeutic, predictive, and prognostic implications. Semin. Oncol. 41, 174–184 (2014).

Gebhardt, C. et al. Myeloid cells and related chronic inflammatory factors as novel predictive markers in melanoma treatment with ipilimumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 5453–5459 (2015).

De Henau, O. et al. Overcoming resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy by targeting PI3Kgamma in myeloid cells. Nature 539, 443–447 (2016).

Ruffell, B. & Coussens, L. M. Macrophages and therapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer Cell 27, 462–472 (2015).

Arlauckas, S. P. et al. In vivo imaging reveals a tumor-associated macrophage-mediated resistance pathway in anti-PD-1 therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaal3604 (2017).

Gregory, A. D. & Houghton, A. M. Tumor-associated neutrophils: new targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 71, 2411–2416 (2011).

Akbay, E. A. et al. Interleukin-17A promotes lung tumor progression through neutrophil attraction to tumor sites and mediating resistance to PD-1 blockade. J. Thorac. Oncol. 12, 1268–1279 (2017).

Ferrucci, P. F. et al. Baseline neutrophils and derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: prognostic relevance in metastatic melanoma patients receiving ipilimumab. Ann. Oncol. 27, 732–738 (2016).

Mariathasan, S. et al. TGFbeta attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature 554, 544–548 (2018).

Koyama, S. et al. Adaptive resistance to therapeutic PD-1 blockade is associated with upregulation of alternative immune checkpoints. Nat. Commun. 7, 10501 (2016).

Shang, B., Liu, Y., Jiang, S. J. & Liu, Y. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating FoxP3+regulatory T cells in cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 5, 15179 (2015).

Arce Vargas, F. et al. Fc-optimized anti-CD25 depletes tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells and synergizes with PD-1 blockade to eradicate established tumors. Immunity 46, 577–586 (2017).

Pauken, K. E. et al. Epigenetic stability of exhausted T cells limits durability of reinvigoration by PD-1 blockade. Science 354, 1160–1165 (2016).

Sen, D. R. et al. The epigenetic landscape of T cell exhaustion. Science 354, 1165–1169 (2016).

Ghoneim, H. E., Zamora, A. E., Thomas, P. G. & Youngblood, B. A. Cell-intrinsic barriers of T cell-based immunotherapy. Trends Mol. Med. 22, 1000–1011 (2016).

Khalil, D. N. et al. The new era of cancer immunotherapy: Manipulating T-cell activity to overcome malignancy. Adv. Cancer Res. 128, 1–68 (2015).

Kim, I. K. et al. Glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor-related protein co-stimulation facilitates tumor regression by inducing IL-9-producing helper T cells. Nat. Med. 21, 1010–1017 (2015).

Chung, Y. et al. CD1d-restricted T cells license B cells to generate long-lasting cytotoxic antitumor immunity in vivo. Cancer Res. 66, 6843–6850 (2006).

Lipson, E. J. et al. Safety and immunologic correlates of Melanoma GVAX, a GM-CSF secreting allogeneic melanoma cell vaccine administered in the adjuvant setting. J. Transl. Med. 13, 214 (2015).

Gabrilovich, D. I., Ostrand-Rosenberg, S. & Bronte, V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 253–268 (2012).

Park, Y. J. et al. Tumor microenvironmental conversion of natural killer cells into myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 73, 5669–5681 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by a research grant (2017K1A1A2004511; to Y.C.) from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education of Korea. D.S.K. is a recipient of the Global Ph.D. Fellowship Program through the NRF (2017H1A2A1042662).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, YJ., Kuen, DS. & Chung, Y. Future prospects of immune checkpoint blockade in cancer: from response prediction to overcoming resistance. Exp Mol Med 50, 1–13 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-018-0130-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-018-0130-1

This article is cited by

-

The prognostic impact of mild and severe immune-related adverse events in non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a multicenter retrospective study

Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy (2022)

-

The role of ERBB4 mutations in the prognosis of advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors

Molecular Medicine (2021)

-

Tumor-immune profiling of CT-26 and Colon 26 syngeneic mouse models reveals mechanism of anti-PD-1 response

BMC Cancer (2021)

-

Generation of T-cell-redirecting bispecific antibodies with differentiated profiles of cytokine release and biodistribution by CD3 affinity tuning

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Safety and efficacy of sintilimab combined with oxaliplatin/capecitabine as first-line treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric/gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma in a phase Ib clinical trial

BMC Cancer (2020)