Abstract

Background:

Ethnic minorities/immigrants have differential health as compared with natives. The epidemic in child overweight/obesity (OW/OB) in Sweden is leveling off, but lower socioeconomic groups and immigrants/ethnic minorities may not have benefited equally from this trend. We investigated whether nonethnic Swedish children are at increased risk for being OW/OB and whether these associations are mediated by parental socioeconomic position (SEP) and/or early-life factors such as birth weight, maternal smoking, BMI, and breastfeeding.

Methods:

Data on 10,628 singleton children (51% boys, mean age: 4.8 y, born during the period 2000–2004) residing in Uppsala were analyzed. OW/OB was computed using the International Obesity Task Force’s sex- and age-specific cutoffs. The mother’s nativity was used as proxy for ethnicity. Logistic regression was used to analyze ethnicity–OW/OB associations.

Results:

Children of North African, Iranian, South American, and Turkish ethnicity had increased odds for being overweight/obese as compared with children of Swedish ethnicity (adjusted odds ratio (OR): 2.60 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.57–4.27), 1.67 (1.03–2.72), 3.00 (1.86–4.80), and 2.90 (1.73–4.88), respectively). Finnish children had decreased odds for being overweight/obese (adjusted OR: 0.53 (0.32–0.90)).

Conclusion:

Ethnic differences in a child’s risk for OW/OB exist in Sweden that cannot be explained by SEP or maternal or birth factors. As OW/OB often tracks into adulthood, more effective public health policies that intervene at an early age are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Immigrants and ethnic minorities in high-income countries often belong to lower socioeconomic groups and have higher rates of chronic diseases, worse self-reported health, and higher infant mortality (1,2,3). Poor health in immigrants and ethnic minorities is reported in adults and children and their descendants; however, differences in health vary considerably by country of origin, destination, time of immigration, acculturation, and disease (4). Immigrants of lower socioeconomic position (SEP) may be predisposed to certain negative health outcomes by virtue of their position in society as well as by ethnic susceptibility resulting from genetic differences and/or mechanisms related to developmental origins of disease (4).

Ethnic differences in levels of child overweight and obesity (OW/OB) and its risk factors, such as unhealthy diet, genetic predisposition, breastfeeding, and maternal smoking, have been substantial enough in some countries to warrant concern (5,6). Becoming overweight/obese may start in childhood and track into adulthood, posing health risks (7). In 2010, nearly 43 million children younger than 5 y of age were overweight worldwide (8). The recent decades have witnessed a significant rise in obesity levels in children across the world with children of lower SEP and ethnic minorities being the worst affected in industrialized nations (5,9,10,11,12,13). Some studies have reported a “leveling off” in the obesity epidemic, which might be country and region specific, but it is generally the more affluent that have benefited from this trend (14,15). In Sweden, nationally representative data for trends in OW/OB in children are lacking. Studies are conducted on regionally representative data often with small sample sizes, and results indicate that OW/OB levels in children are falling, but socioeconomic differences still exist, at least in urban areas (16,17,18,19,20).

In the adult Swedish population, there has been an overall increase in the prevalence of being overweight/obese. The prevalence of OW/OB increased from 35% in 1980 to 53% in 2009 among men, and from 26 to 37% among women for the same years (21).

The role of socioeconomic factors (education, family income, and occupation, among others) in the health of immigrants and ethnic minorities is debated. Some, but not all, studies have found that these factors partly explain ethnic differences in certain health outcomes (22,23,24). The role of parental socioeconomic factors in creating differences in the proportions of children who are overweight/obese between immigrant groups needs further investigation.

The number of “foreign-born” residents in Sweden has doubled over the past four decades and the number of residents with “both parents born abroad” has been increasing continuously (13.4 and 17.34%, respectively, in 2007) (21).

We investigated (i) if ethnicity by mother’s country of birth was associated with the odds of being overweight/obese in children born in Sweden aged 4–5 y, (ii) if this association could be explained by differences in parental SEP and/or health behaviors and early-life factors (breastfeeding, maternal smoking, maternal BMI, and birth weight), and (iii) if the association differed by gender. Identification of immigrant groups at increased risk for being overweight/obese can help in designing public health interventions that target high-risk children at an early age, preferably before the onset of OW/OB.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Characteristics of the children and their parents (n = 10,628) are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 . Mean BMI of all children was 16.11 kg/m2 (56th percentile). Boys had slightly higher mean BMI than girls. A higher percentage of girls (19%) than boys (14%) were overweight/obese, with the overall prevalence being 16.5%. The distribution of number of children per mother was as follows: 7,618 mothers (84%) had 1 child each, 1,448 mothers (16%) had 2 children, and 38 mothers (0.5%) had 3 children.

Differences between maternal and paternal characteristics are presented in Table 2 .

Unadjusted Associations Between Parental Characteristics and Odds of Being OW/OB

Increasing levels of parental education were associated with lower risk of being overweight/obese in children (those with research degree had the lowest proportions of overweight/obese children relative to the least educated parents (≤9 y of education)—13 vs. 20% and 13 vs. 19% for fathers and mothers, respectively, P < 0.001 for either parent) (Supplementary Table S1 online). Statistically significant differences were found in proportions for OW/OB by family status, breastfeeding, and maternal smoking. Single parents had higher proportions of overweight/obese children than married parents. Mothers who exclusively breastfed for 6 mo had the lowest proportion of overweight/obese children as compared with those who partly breastfed/did not breastfeed. Mothers who reported smoking had a greater proportion of overweight/obese children as compared with nonsmokers. Detailed results on unadjusted analyses can be seen in the Supplementary Table S1 online.

Associations Between Socioeconomic Characteristics and Odds of Being OW/OB

Children of parents with ≥3 y of college and research degree had decreased odds for being overweight/obese as compared with children of parents with ≤9 y of education (odds ratio (OR): 0.72, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.59–0.88, 0.63, 0.44–0.89, respectively, for mothers and OR: 0.63, 95% CI: 0.52–0.77, 0.58, 0.44–0.77, respectively, for fathers, adjusted for the child’s age and gender). However, after adjustment for maternal BMI, there was no evidence of an association between education and odds of being overweight/obese. Parental income was not significantly associated with the odds of a child being overweight/obese (data not shown).

Associations Between Nativity and Odds of Being OW/OB

Prevalence of OW/OB in children varied statistically significantly according to maternal nativity, with North African, South American, and Turkish mothers having the highest proportions of overweight/obese children (28, 32, and 31%, respectively). The Finns had the lowest proportion of overweight/obese children (11%), whereas Swedish and Western European mothers had 16 and 19%, respectively, of their children classified as overweight/obese (Supplementary Table S1 online).

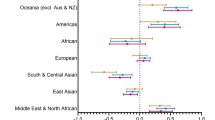

In all logistic regression models we found statistically significant differences in odds for children being overweight/obese between Swedish born mothers and those born in other countries: North Africa, Finland, South America, and Turkey (unadjusted OR: 1.96 (95% CI: 1.20–3.17), 0.60 (0.37–0.98), 2.53 (1.60–4.02), and 2.31 (1.41–3.80), respectively). These were statistically significant in models 1–4, and the strength of the associations increased marginally on adjustment for covariates ( Table 3 ).

Addition of socioeconomic covariates (model 2) did not change the OR materially for any of the four groups. Additional adjustment for breastfeeding, maternal smoking, and birth weight (early-life factors) led to an increase in the OR by 20–40% in those groups that already had significantly increased odds for OW/OB. Additional adjustment for maternal BMI (model 4) slightly increased the strength of the associations, with stronger effects in the North African and Turkish groups. Children of Iranian mothers also had increased odds of being overweight/obese but only in models adjusted for early-life factors and maternal BMI (models 3 and 4).

When father’s nativity was instead the principle exposure, children of North African–, Middle Eastern–, South American–, and Turkish-born fathers had increased odds for being overweight/obese after adjusting for all covariates ( Table 4 ). The increased odds for being overweight/obese previously observed for Iranian children (according to mother’s country of birth) lost their statistical significance. When both maternal and paternal nativity were included as covariates, there was statistically significant evidence of an independent association with OW/OB for maternal (P < 0.0001), but not for paternal (P = 0.70), nativity.

In analyses stratified by sex, the significantly increased ORs for being overweight/obese in North African and Turkish children were observed only in boys (Supplementary Table S2 online). However, both South American boys and girls had significantly increased ORs for OW/OB, although the ORs were consistently higher for boys. Finnish girls but not boys had a significantly decreased OR for OW/OB. However, formal tests for interaction were nonsignificant.

Discussion

Main Findings of the Study

Our study reveals that Swedish children aged 4–5 y belonging to certain maternal nativity groups—North African, Iranian, South American, and Turkish—have increased risk for being overweight/obese that cannot be explained by parental SEP or by early-life factors. Our results suggest that the mother’s nativity, used as a proxy for ethnicity, may be more strongly associated with a child’s OW/OB than the father’s nativity.

Comparison With Similar Studies

As this is the first study in Sweden to investigate ethnicity and OW/OB in childhood in detail (using regional/country-specific categorization of parental nativity, and accounting for early-life factors), we cannot make any direct comparisons to other studies. One Swedish study that investigated ethnic differences in OW/OB in children used a smaller study sample (n = 2,306) and classified subjects only into “Nordic” and “non-Nordic” origin (25). The authors found a higher proportion of overweight among non-Nordic children.

Several studies have investigated the association of ethnicity and OW/OB in children in high-income countries with large populations of immigrants and ethnic minorities. Almost all showed increased risks for certain ethnic groups. In studies conducted in the United States, Hispanic and African-American children generally have increased risks for being overweight/obese (23,26). Similarly, studies from the United Kingdom, Holland, Germany, and Norway also showed increased risks for being overweight/obese or higher mean BMI in ethnic minority children (11,27,28).

An interesting finding from our study was that key socioeconomic indicators could not explain the association between nativity and OW/OB (additional adjustment for parental SEP did not change the odds for OW/OB in nativity groups in this study sample). Other studies show inconsistent results in this regard. Studies from the United States and United Kingdom—one using a cruder indicator of SEP (eligibility for free lunch in schools) and the others using several indicators including free lunch eligibility, crowding index, and parental employment—found that SEP did not explain the association between ethnicity and BMI or OW/OB in children (26,29). By contrast, German and other American studies found that parental SEP partly explained the crude association between ethnicity and OW/OB in children (5,12).

As in other similar studies, we also observed clearly different effect sizes by gender, but interaction tests were statistically nonsignificant, possibly due to small numbers in some of the strata.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

The study subjects were born recently (2000–2004), making this is a “contemporary” cohort, and results are applicable for future public health interventions. The large sample size included a large proportion of children aged 4–5 living in Uppsala, making the study sample representative of this county.

Results from our study may apply to other regions in Sweden because community services including health care are relatively similar across the country.

The proportion of foreign-born parents included in our study population of 10,628 is 13%, similar to the 14.3% proportion of foreign-born residents in Sweden in 2009. Uppsala has a large university and levels of education are probably higher than the national average. Immigrant/ethnic minority groups residing in Uppsala are likely to have higher educational levels than immigrant/ethnic groups in other parts of the country. This could be why socioeconomic indicators used in this study did not explain the ethnicity–OW/OB associations. The associations between nativity/ethnicity and OW/OB in other regions of the country are more likely to be stronger and explained by socioeconomic indicators where immigrant/ethnic groups have lower SEP.

BMI is only a crude measure of body fat, but it is argued to be one of the best single measures for use in large-scale epidemiological studies and is more acceptable than skin-fold measures in children. The widely used International Obesity Task Force’s cutoffs for OW/OB in children are based on internationally pooled data from six countries, none of which are well represented in our study sample (30). Nonetheless, the International Obesity Task Force’s cutoffs are based on sex-specific growth curves and account appropriately for both age and sex. Our estimates for obesity should not be biased in this regard.

Height and weight used to calculate BMI could be misclassified because they are measured by different nurses at various clinics as part of routine examinations. However, we do not believe this will bias our results, as we do not believe that this misclassification is differentially based on a child belonging to an ethnic/immigrant minority or being ethnic Swedish.

The loss of study participants due to missing data, primarily in childhood OW/OB, maternal breastfeeding, and maternal BMI, is a weakness. Our complete case (CC) results for each model are valid provided missingness is independent of the outcome (OW/OB) after adjusting for the model’s covariates. This assumption cannot be verified from the data, but we believe it is plausible, particularly for the models that—in addition to ethnicity, age, and sex—also adjust for socioeconomic factors: income, education, and father’s family status.

Educational levels of immigrants are systematically underestimated and significant associations seen between parents’ education and OW/OB in children could be slightly overestimated (31).

Few studies have addressed groups of mixed ethnicities. Children of mixed ethnic heritage may have different risks for OW/OB as compared with single-ethnicity groups. In our study sample, 13% of subjects are of mixed nativity, which was not similar across the different nativity groups, indicating that people of certain nativities are more likely to marry Swedes or people belonging to their own/similar nativity groups and backgrounds. For example, more Finns and immigrants from other Western European countries were likely to be married to Swedes as compared with immigrants from the Middle Eastern countries and Iran, who were likely to be married to people from their regions of origin. We were unable to examine this group of mixed nativity separately due to insufficient numbers.

Given the young age of children in the study, we speculate that mothers play a greater role in determining their children’s diet (which is closely tied to ethnic traditions and perceptions (6)) than fathers. Therefore, we focused on the mother’s nativity (the proxy for her ethnicity) instead of the father’s. In the additional regression model 5, adjustment for paternal nativity only marginally reduced the statistically significant associations between maternal nativity and odds of being overweight/obese, indicating that maternal nativity had an effect largely independent of paternal nativity.

Another strength is inclusion of two well-established indicators of SEP, previously shown to partly explain the crude influence in the association between ethnicity and childhood risk of being overweight/obese.

Using country of birth/nativity as a proxy for ethnicity has limitations. Not all people born in a country necessarily have the ethnicity associated with it. However, we believe that only a minority of people born in a particular country would have an ethnicity associated with another. Those who do are more likely to be from neighboring countries with similar cultural and ethnic origins. Nonetheless, we did not have sufficient numbers to categorize subjects solely by country of origin, and in most instances we had to use regional groupings of countries based on geographical locations widely used in similar studies on ethnicity and health. Ethnicity is not recorded in any of the routine registers, and country of birth is the only available variable for identifying ethnicity. Another weakness is exclusion of nativity groups with small numbers (South Asians and Africans).

It is possible that the association between nativity and OW/OB in childhood is mediated by factors not measured in this study, such as genetic predisposition or diet, which significantly affects body fat composition and BMI. Other early-life factors previously shown to vary by ethnicity and to increase risk for childhood obesity include maternal depression, infant sleep, television watching, physical activity, and weight gain during infancy, for which we lacked data (32,33).

Interpretation

We speculate that the increased risk for OW/OB in certain maternal nativity groups of children is primarily due to differences in genetics and culture (which in part constitute ethnicity). The importance of genetic susceptibility to becoming overweight was highlighted in a Swedish study that showed adoptees from South America, specifically Chile, had increased OR for being overweight as compared with native Swedish children. These children grew up in Swedish households with a Swedish lifestyle including diet (34). Our results also indicate that children of South American descent are more vulnerable because they had the highest OR for OW/OB, consistent across all models regardless of adjustments, and in sex-stratified analysis. A substantial proportion of children in our study classified as South American had parents born in Chile (n = 37 or 40% of all South Americans). The observed estimated OR marginally increased on adjustment for early-life factors including birth weight, maternal BMI, and breastfeeding, which capture maternal nutrition and genetics to some extent.

SEP varies by ethnicity (in this study sample it varied by both parental income and education). However, after adjustment for nativity, SEP had no independent association with the odds of being overweight/obese. The relationship between ethnicity and SEP is complex. Socioeconomic gradients in OW/OB probably evolve over time with dynamic interactions between acculturation and socioeconomic advancement, which also depend on other factors including gender, age, religious and traditional beliefs, and country of origin, and it is still possible that parental SEP in ethnic minorities becomes more important at a later stage when the children are older (4). It is also likely that we lack statistical power to detect any possible mediating role of parental SEP within ethnic minority groups. The finding that children of Finnish mothers had a decreased risk for OW/OB is partly explained by nonrandom missingness in maternal BMI: in contrast to the children of Swedish maternal nativity, the risk of being overweight/obese for children of Finnish maternal nativity with maternal BMI available was lower than the risk for those with missing maternal BMI, such that in the CCs, children of Finnish maternal nativity had lower risk of OW/OB.

Conclusion

Obesity in childhood may have significant long-term physical and psychosocial consequences. Although there is no immediate risk for any major illness, studies have documented early development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in overweight/obese children. Ethnic differences in the proportions of overweight/obese children are contextual. The same ethnic groups in different countries may not necessarily have the same risk of being overweight/obese. From our results, it is apparent that further studies are needed using larger nationally representative study populations. How ethnic differences in OW/OB change across the life-course as children develop into adults needs to be studied. Such investigations could help in understanding mechanisms underlying OW/OB and framing health interventions that may target modifiable risk factors such as lifestyle (unhealthy diet or lack of physical activity), ensuring equitable health care access including screening of risk factors, and early intervention can save children from becoming overweight/obese.

Methods

The study sample was drawn from a population of children born during the period 2000–2004, registered as residents in Uppsala county, Sweden (n = 20,520) when they were aged 4–5 y ( Figure 1 ) (35). Of these, 19,123 were born in Sweden and had data on birth weight. The study sample was first restricted to singletons (n = 18,555) and then to children who attended annual routine examinations at child health care centers when anthropometric measurements (height and weight—used to compute BMI) were recorded and whose valid BMI at the age of 4 or 5 y was available. For children who had not yet completed the examination at the age of 5, measurements from the examination at the age of 4 y were included. Therefore, the BMI of 10,509 children aged 5 y (born during the years 2000–2003) and 4,331 children aged 4 y (born 2000–2004 and with BMI at age 5 missing) were included. Children were classified as being overweight or obese using age- and sex-specific cutoffs proposed by the International Obesity Task Force (30). Of the 14,840 children with valid BMI data, 10,628 had complete data on parental socioeconomic variables, maternal BMI, smoking during pregnancy, and breastfeeding.

Flowchart explaining how the study sample for this investigation was conceived. SEP, socioeconomic position.

Data on the child’s birth weight, date of birth, sex, mother’s BMI before pregnancy, multiple births, and mother’s smoking habits were accessed through linkage (using personal identity numbers) with the Medical Birth Registry. Mothers were classified as overweight (25–29.99 kg/m2) or obese (≥30 kg/m2) using World Health Organization criteria. Smoking at time of registration at maternal health clinics (generally reflecting smoking habits during the first trimester of pregnancy) was used in the analysis. Mothers were grouped into nonsmokers and smokers.

Information on breastfeeding was collected retrospectively by questioning mothers on feeding habits when the child was aged 6 mo and was available from the database of the Child Health Care Unit, Uppsala County, consisting of child health records reported by nurses in Child Health Centres. In our analyses, breastfeeding was treated as a binary variable (exclusive breastfeeding for 6 mo and partly breastfed/no breastfeeding).

Parental education, disposable income, country of birth, and family status (married, partnership/cohabitation, or single) were obtained from Statistics Sweden. Parental education was based on the highest level achieved and recorded in the Education Registry until 2001. It was categorized as follows: ≤9 y of school, 2 y of high school, 3 y of high school, <3 y of university/college, and ≥3 y of university/college and research education.

Parental disposable income was based on income data collected at the year of examination, i.e., when the child was aged 4 or 5 y and was divided into quartiles for analyses. It is an aggregate variable that takes into account all incomes earned in a household after taxes, as well as any monetary social benefits that may have been received, and is adjusted for family size. Ethnicity is not recorded as a variable in Swedish routine registers and mother’s country of birth/nativity was used as the main exposure variable in our analysis and as a proxy for ethnicity. Countries were first grouped into the following regions: (i) Sweden (reference), (ii) Western Europe and North America, (iii) South America, (iv) Eastern Europe, (v) North Africa, (vi) East Asia, and (vii) Middle East. Those countries that had sufficient numbers (a minimum of n = 80) were excluded from the above regional groupings and classified as separate categories. These included Iran, Finland, and Turkey. A total of 138 children whose parents were born in South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka) and Africa (except Northern Africa) were excluded due to insufficient numbers.

Statistical Analysis

Children with a BMI <9.24 kg/m2 (i.e., 4 SD below the mean) were excluded from analyses. The child’s maternal nativity was the principle exposure variable. Children with mothers of Swedish nativity were the reference group in all analyses.

Associations between the child’s overweight/obese status and parental characteristics (nativity group, maternal smoking, breastfeeding, family status, and education) were first analyzed by χ2-square tests. Logistic regression was then used to analyze associations between children’s OW/OB (binary) and the above parental exposures (adjusted for child’s age and sex).

Multivariable logistic regression models were fitted with the child’s overweight/obese status as outcome and the child’s maternal nativity as the primary exposure. Model 1, in addition, included child’s age and sex as covariates. Subsequent models were fitted by grouping covariates into socioeconomic factors and lifestyle/early-life factors. Four models with additional covariates were fitted—model 2: model 1 covariates + adjustment for socioeconomic factors such as income and education of both parents and father’s family status; model 3: model 2 covariates + adjustment for breastfeeding, maternal smoking, and birth weight; model 4: model 3 covariates + adjustment for maternal BMI; and in a separate analysis (model 5), model 4 was run with the addition of father’s nativity (categorized in the same way as mother’s nativity variable). We ran the same logistic regression models stratified by sex of the child. Differences in the nativity–OW/OB associations between males and females were formally tested using interactions.

Robust standard errors allowing for clustering of children within families were used for all logistic regression models.

Missing Data

Mother’s BMI, her smoking status, and breastfeeding habits were missing for 17, 3, and 9% of children, respectively, who had complete data on valid BMI, parental nativity, and SEP (n = 14,296, Figure 1 ). This left 10,628 children available for CC analyses.

CC analysis gives valid results if the probability of being a CC is independent of the outcome (OW/OB), given the model covariates (36). Missingness occurred primarily in child OW/OB, maternal breastfeeding, and maternal BMI ( Figure 1 ). It is plausible that missingness in each of these variables is independent of the child’s overweight/obese status, given the logistic regression covariates, implying validity of the CC analysis, although this assumption cannot be verified from the observed data. Because we fitted a series of logistic regression models with increasing levels of adjustment for potential confounders, the assumption of conditional independence is more plausible for the more complex models (i.e., model 4). Multiple imputation was not implemented due to the clustered nature of the data, which cannot be accommodated by standard imputation routines. Our results are, thus, based on the 10,628 CCs.

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 11 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

The study sample was drawn from the register of statistics of the Child Health Care Unit in Uppsala County. The data were collected with parental consent and linked to national registers (Statistics Sweden and the National Board of Health and Welfare) using personal identity numbers of the child. Permission to conduct the study was granted by the regional ethics committee in Uppsala, Sweden.

Statement of Financial Support

J.W.B. was supported by UK Medical Research Council grant G0900724. A.R.K. and I.K. were funded by Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research project no. 2006-1518.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Kington RS, Smith JP . Socioeconomic status and racial and ethnic differences in functional status associated with chronic diseases. Am J Public Health 1997;87:805–10.

Mutchler JE, Burr JA . Racial differences in health and health care service utilization in later life: the effect of socioeconomic status. J Health Soc Behav 1991;32:342–56.

Williams DR . Race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status: measurement and methodological issues. Int J Health Serv 1996;26:483–505.

Bhopal R . Ethnicity, Race, and Health in Multicultural Societies. Foundations for better epidemiology, public health, and health care, 1st edn. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Orsi CM, Hale DE, Lynch JL . Pediatric obesity epidemiology. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2011;18:14–22.

Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman K, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL . Racial/ethnic differences in early-life risk factors for childhood obesity. Pediatrics 2010;125:686–95.

Eriksson J, Forsén T, Osmond C, Barker D . Obesity from cradle to grave. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003;27:722–7.

Obesity and Overweight, Factsheet. World Health Organization technical report series. (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/.) Accessed November 2011.

Due P, Damsgaard MT, Rasmussen M, et al.; HBSC obesity writing group. Socioeconomic position, macroeconomic environment and overweight among adolescents in 35 countries. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33:1084–93.

Singh GK, Kogan MD, Van Dyck PC, Siahpush M . Racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and behavioral determinants of childhood and adolescent obesity in the United States: analyzing independent and joint associations. Ann Epidemiol 2008;18:682–95.

Balakrishnan R, Webster P, Sinclair D . Trends in overweight and obesity among 5-7-year-old White and South Asian children born between 1991 and 1999. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008;30:139–44.

Will B, Zeeb H, Baune BT . Overweight and obesity at school entry among migrant and German children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2005;5:45.

Baruffi G, Hardy CJ, Waslien CI, Uyehara SJ, Krupitsky D . Ethnic differences in the prevalence of overweight among young children in Hawaii. J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104:1701–7.

Wardle J, Brodersen NH, Cole TJ, Jarvis MJ, Boniface DR . Development of adiposity in adolescence: five year longitudinal study of an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample of young people in Britain. BMJ 2006;332:1130–5.

Stamatakis E, Wardle J, Cole TJ . Childhood obesity and overweight prevalence trends in England: evidence for growing socioeconomic disparities. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:41–7.

Blomquist HK, Bergström E . Obesity in 4-year-old children more prevalent in girls and in municipalities with a low socioeconomic level. Acta Paediatr 2007;96:113–6.

Sjöberg A, Lissner L, Albertsson-Wikland K, Mårild S . Recent anthropometric trends among Swedish school children: evidence for decreasing prevalence of overweight in girls. Acta Paediatr 2008;97:118–23.

Sundblom E, Petzold M, Rasmussen F, Callmer E, Lissner L . Childhood overweight and obesity prevalences levelling off in Stockholm but socioeconomic differences persist. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1525–30.

Ekblom OB, Bak EA, Ekblom BT . Trends in body mass in Swedish adolescents between 2001 and 2007. Acta Paediatr 2009;98:519–22.

Bergström E, Blomquist HK . Is the prevalence of overweight and obesity declining among 4-year-old Swedish children? Acta Paediatr 2009;98:1956–8.

Statistical Yearbook of Sweden 2009. Stockholm, Sweden: Statistics Sweden, 2009.

Nicklett EJ . Socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity independently predict health decline among older diabetics. BMC Public Health 2011;11:684.

Wang Y, Beydoun MA . The obesity epidemic in the United States–gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev 2007;29:6–28.

Wang Y, Zhang Q . Are American children and adolescents of low socioeconomic status at increased risk of obesity? Changes in the association between overweight and family income between 1971 and 2002. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:707–16.

Sjöberg A, Hulthén L . Anthropometric changes in Sweden during the obesity epidemic–increased overweight among adolescents of non-Nordic origin. Acta Paediatr 2011;100:1119–26.

Johnson SB, Pilkington LL, Deeb LC, Jeffers S, He J, Lamp C . Prevalence of overweight in north Florida elementary and middle school children: effects of age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. J Sch Health 2007;77:630–6.

Kumar BN, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Lien N, Wandel M . Ethnic differences in body mass index and associated factors of adolescents from minorities in Oslo, Norway: a cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr 2004;7:999–1008.

de Wilde JA, van Dommelen P, Middelkoop BJ, Verkerk PH . Trends in overweight and obesity prevalence in Dutch, Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese South Asian children in the Netherlands. Arch Dis Child 2009;94:795–800.

Taylor SJ, Viner R, Booy R, et al. Ethnicity, socio-economic status, overweight and underweight in East London adolescents. Ethn Health 2005;10:113–28.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH . Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240–3.

Statistics Sweden. Background facts, evaluation of the Swedish Register of Education. (http://www.scb.se/statistik/_publikationer/BE9999_2006A01_BR_BE96ST0604.pdf.) Accessed 2 January 2013.

Stettler N, Zemel BS, Kumanyika S, Stallings VA . Infant weight gain and childhood overweight status in a multicenter, cohort study. Pediatrics 2002;109:194–9.

Dubois L, Girard M . Early determinants of overweight at 4.5 years in a population-based longitudinal study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:610–7.

Johansson-Kark M, Rasmussen F, Hjern A . Overweight among international adoptees in Sweden: a population-based study. Acta Paediatr 2002;91:827–32.

Wallby T, Hjern A . Region of birth, income and breastfeeding in a Swedish county. Acta Paediatr 2009;98:1799–804.

Seaman SR, White IR . Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res 2013;22:278–95.

Acknowledgements

We thank Anders Hjern, Centre for Health Equity Studies, Karolinska Institutet/Stockholm University, for access to data and comments on previous versions of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table S1.

(DOC 69 kb)

Supplementary Table S2.

(DOC 78 kb)

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khanolkar, A., Sovio, U., Bartlett, J. et al. Socioeconomic and early-life factors and risk of being overweight or obese in children of Swedish- and foreign-born parents. Pediatr Res 74, 356–363 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2013.108

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2013.108

This article is cited by

-

The influence of immigrant background and parental education on overweight and obesity in 8-year-old children in Norway

BMC Public Health (2023)

-

Cardiometabolic risk profile among children with migrant parents and role of parental education: the IDEFICS/I.Family cohort

International Journal of Obesity (2023)

-

Adapting a South African social innovation for maternal peer support to migrant communities in Sweden: a qualitative study

International Journal for Equity in Health (2022)

-

Does eating behaviour among adolescents and young adults seeking obesity treatment differ depending on sex, body composition, and parental country of birth?

BMC Public Health (2022)

-

Prevalence of obesity in Italian adolescents: does the use of different growth charts make the difference?

World Journal of Pediatrics (2018)