Abstract

Permanent closure of the newborn ductus arteriosus requires the development of neointimal mounds to completely occlude its lumen. VEGF is required for neointimal mound formation. The size of the neointimal mounds (composed of proliferating endothelial and migrating smooth muscle cells) is directly related to the number of VLA4+ mononuclear cells that adhere to the ductus lumen after birth. We hypothesized that VEGF plays a crucial role in attracting CD14+/CD163+ mononuclear cells (expressing VLA4+) to the ductus lumen and that CD14+/CD163+ cell adhesion to the ductus lumen is important for neointimal growth. We used neutralizing antibodies against VEGF and VLA-4+ to determine their respective roles in remodeling the ductus of premature newborn baboons. Anti-VEGF treatment blocked CD14+/CD163+ cell adhesion to the ductus lumen and prevented neointimal growth. Anti-VLA-4 treatment blocked CD14+/CD163+ cell adhesion to the ductus lumen, decreased the expression of PDGF-B (which promotes smooth muscle migration), and blocked smooth muscle influx into the neointimal subendothelial space (despite the presence of increased VEGF in the ductus wall). We conclude that VEGF is necessary for CD14+/CD163+ cell adhesion to the ductus lumen and that CD14+/CD163+ cell adhesion is essential for VEGF-induced expansion of the neointimal subendothelial zone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Closure of the full-term ductus arteriosus after birth occurs in two phases. First, smooth muscle constriction narrows the ductus lumen. Then, anatomic remodeling permanently occludes the lumen. In contrast with the full-term ductus, the preterm ductus frequently fails to narrow its lumen or undergo anatomic remodeling. Remodeling of the preterm ductus will occur if it can be made to constrict tightly and obstruct luminal blood flow (1).

Several of the steps involved with ductus remodeling have been elucidated. The initial constriction creates a zone of ischemic hypoxia within the ductus muscle media that seems to be the required stimulus for the following anatomic changes: 1) formation of neointimal mounds (composed of proliferating luminal endothelial cells and migrating medial smooth muscle cells expanding the intima's subendothelial space), 2) vasa vasorum proliferation within the muscle media, and 3) smooth muscle cell death (2). Although the cell death and penetration of vasa vasorum into the ductus wall seem to be due to profound ATP depletion (3,4) and VEGF induction (5), respectively, the mechanism(s) responsible for the neointimal changes are still unknown.

In mice, platelets and platelet thrombi seem to be essential for permanent closure of the ductus lumen (6). In contrast, in human and nonhuman primates, recent studies suggest that platelets are not required for permanent ductus closure (7).

Inflammatory processes play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of several vascular disorders (8,9). During atherogenesis, direct interactions between circulating monocytes and luminal endothelial cells increase the synthesis of factors, such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9, that facilitate the migration of smooth muscle cells into the expanding neointima (10,11). We previously hypothesized that the attachment of circulating mononuclear cells to the ductus luminal endothelium may also be essential for ductus neointima formation (12). This hypothesis is supported by several observations: following ductus constriction, endothelial cells lining the lumen increase their expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), an important ligand for the mononuclear cell adhesion receptor, VLA-4 (also known as integrin α4β1 or CD49d) (12,13); paralleling the increase in VCAM-1, VLA-4+ mononuclear cells increase their adherence to the ductus lumen (12); and, finally, the degree of VLA-4+ mononuclear cell adherence to the ductus lumen is associated with the extent of neointimal remodeling of the ductus (12).

The factors responsible for attracting circulating mononuclear cells to the ductus wall are still unknown. The hypoxia-inducible growth factor, VEGF, seems to play an important role in ductus neointimal mound formation and vasa vasorum ingrowth (1,5,12). VEGF promotes the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells (14,15). VEGF is also a direct chemoattractant for monocytes (16,17).

In the experiments described below, we used neutralizing antibodies against VEGF and VLA-4+ to determine their roles in mononuclear cell adhesion and ductus neointima formation in preterm baboons.

METHODS

VLA-4 inhibition—in vivo.

Animal experiments were approved (by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee) and performed at the Southwest National Primate Research Center in San Antonio, TX. Complete descriptions of the animal care and surgical procedures have been published elsewhere (5,12). Briefly, timed pregnant baboon (Papio papio) dams were delivered by C-section at 125 + 1 d gestation (full term = 185 d); their fetuses were either a) euthanized before breathing (Fetal Controls) or b) mechanically ventilated for 6 d (Newborn groups) at which point the animals were euthanized. Preterm newborn baboons usually fail to constrict and obstruct their ductus luminal blood flow unless they are treated with inhibitors of both prostaglandin and NO production (1). Therefore, all preterm newborn baboons were treated with a combination of indomethacin (Indocin, 0.1 mg/kg/dose, given i.v. at 24, 48, 72, 84, 96, 108, 120, and 132 h after delivery) and N-nitro-l-arginine (a NOS inhibitor: 6 mg/kg/h as a continuous infusion, starting at 50 h after delivery and continuing until necropsy). Preterm newborn baboons were randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups: 1) Controls (no antibody treatment), 2) anti-VLA-4-treated newborns, and 3) anti-VEGF-treated newborns. Because of the expense and need to restrict the use of this precious animal model, we were limited in the number of animals we could study. As a result, we were not able to have a Control group that received an isotype control antibody. The anti-VLA-4 newborns (group 2) received two i.v. doses (5 mg/kg) of HP1/2 (a humanized anti-VLA-4 MAb; Biogen Idec, Cambridge, MA) (18) at 24 and 72 h after delivery. Similar doses of HP1/2 have been shown to reduce mononuclear cell adhesion to arterial walls in mice (19), rabbits (20), pigs (21), and baboons (18). The anti-VEGF newborns (group 3) received a single i.v. dose (10 mg/kg) of a neutralizing MAb made against VEGF (MAb A.4.6.1; Genentech, San Francisco, CA) (22,23) 24 h after delivery (5). The animals in the anti-VEGF group (group 3) have been previously reported (5); however, the findings presented below were not included in the original report.

A complete echocardiographic examination including assessment of ductal patency was performed daily (1). At necropsy, the ductus was dissected in 4°C PBS solution and a) embedded and frozen in Tissuetek (American Master Tech, Merced, CA) for immunohistochemistry (newborn baboon groups 1, 2, and 3), and/or b) frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA analysis (newborn baboon groups 1 and 2). Tissue was not available for RNA analysis from the group 3 animals.

Flow cytometry.

To identify the cell populations most likely to be affected by the anti-VLA-4 antibody, HP1/2, we used multicolor direct immunofluorescence, as previously described (24,25). The antibodies used were anti-human CD3 (clone SP34–2; BD Biosciences), CD8 (clone SK1; BD Biosciences), CD14 (clone 322A-1; Beckman-Coulter), CD31 (clone WM59; Biolegend), CD45 (clone DO58–1283; Biolegend), and CD49d (clone AF10; Biolegend).

Quantitative PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from each individual ductus (26). Gene expression was quantified using TaqMan Universal PCR master mix, Taqman probes, and ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence detection system as previously described (3,26). The degree of expression of the gene of interest was determined using the relative gene expression method. Malate dehydrogenase (MDH) was used as an internal control to normalize the data (12,27). ΔCT represents the difference in cycle threshold between the expression of the housekeeping gene, MDH, and the gene of interest. Each unit of ΔCT represents a 2-fold change in a gene's mRNA. The more negative the ΔCT, the fewer the number of starting copies of a gene (mRNA).

We have previously shown that the expression of HIF1α mRNA in the ductus arteriosus correlates with the degree of smooth muscle hypoxia (3). In our real-time PCR experiments, we used HIF1α as a surrogate marker for hypoxia.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry protocols were similar to those reported previously (1,12,28). Endothelial cells were detected with anti-eNOS (Clone 3; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and anti-VE cadherin (F-8; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Both antibodies showed identical findings. Monocytes/macrophages were detected with anti-CD163 (GHI/61; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-CD14 (TUKU; Dako, Carpenteria, CA). Both antibodies showed identical findings. Antibodies against the following antigens were used to identify T-lymphocytes [CD3 (rabbit polyclonal); Dako], T cells/NK cells [CD8 (UCH-T4); Santa Cruz Biotechnology], dendritic cells [CD83 (HB15a); Santa Cruz Biotechnology], and granulocytes [neutrophil elastase (NP57); Dako]. Antibodies against GP1bα (AN51; Dako) were used to identify platelets. Antibodies against VCAM-1 (1G11; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used to identify adhesion molecules expressed by activated endothelial cells. The number of positively stained cells lining the ductus lumen was expressed per 100 luminal-lining cells.

Histologic measurements in the newborn ductus were made at the level of minimal luminal area, which was determined from 6 μm serial cross-sections. The neointimal zone was defined as the region between the lumen and the internal elastic lamina (identified by phase contrast microscopy). The endothelial zone of the neointima was the luminal cell layer(s) that stained positive for eNOS (endothelial NO synthase) and VE-cadherin (vascular endothelial cell cadherin). The subendothelial zone was defined as the region between the luminal endothelial cells and the internal elastic lamina. Neointimal dimensions were determined by averaging measurements made from eight predetermined regions of the section, using an overlay template and NIH ImageJ software.

Mononuclear cells and vasa vasorum invade the ductus muscle media from the surrounding adventitia (see below). To determine the extent of muscle media invasion by mononuclear cells and vasa vasorum, we used an overlay template, containing a grid, and NIH ImageJ software to divide the muscle media into eight clock-hours sections. In each section of the wall, we measured the maximal distance that the cells migrated from the adventitia into the media (expressed as a percent of the distance from the adventitia to the internal elastic lamina in that section of the wall). The maximal distances from each of the eight sections of the ductus wall were averaged and reported as “% muscle media thickness” for that vessel.

Statistics.

Results are presented as means ± SD and percentages. Intergroup differences were evaluated with either a Chi-square analysis, or unpaired t test. When more than one comparison was made, Bonferroni's correction was used.

RESULTS

Combined treatment with indomethacin and N-nitro-l-arginine produced constriction of the ductus arteriosus and complete loss of Doppler-demonstrable luminal blood flow in all of the preterm newborn baboons. Neither the anti-VLA-4 MAb nor the anti-VEGF MAb affected the rate of ductus constriction measured by daily pulsed-Doppler examinations [age of Doppler-demonstrable ductus closure: group 1 (Control newborns, n = 18) = 79 ± 31 h; group 2 (anti-VLA-4, n = 8) = 91 ± 28 h; group 3 (anti-VEGF, n = 6) = 88 ± 24 h].

We used HIF1α mRNA expression as a surrogate marker for ductus hypoxia. There was a significant increase in HIF1α expression between fetus and newborns after postnatal closure (Table 1) (3); however, there was no difference in HIF1α expression between newborns in the Control group (group 1) and those treated with anti-VLA-4 MAb (group 2; Table 1). Nor were there differences in the degree of hypoxia between the Control (group 1) and the anti-VEGF-treated newborns (group 3), previously reported in Ref. 5.

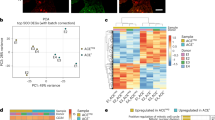

Distribution of VLA-4 (CD49d) on baboon leukocytes.

To identify the cell populations most likely to be affected by the anti-VLA-4 antibody, HP1/2, we used flow cytometry to determine the distribution of expression of VLA-4 on umbilical cord blood leukocytes obtained from four fetal baboons. VLA-4 was expressed on the surface of 64 ± 17% (mean ± SD) of baboon monocytes (defined as CD45+ CD14+ or CD45+ CD163+ cells), and 0 ± 0% of baboon granulocytes (large cells that were CD45+ and CD14− CD163−). This distribution is similar to what we observed in human cord blood monocytes (80 ± 18% expressed VLA-4) and granulocytes (0 ± 0%). On the other hand, the percentage of baboon T cells that expressed VLA-4 was significantly less than the percentage of human T cells that expressed VLA-4: CD4+ T cells (defined as CD45+ CD3+ CD14− CD8−) cells: baboon = 8 ± 2%, human = 84 ± 7% expressed VLA-4; CD8+ T cells (defined as CD45+ CD3+ CD14− CD8+) cells: baboon = 18 ± 5%, human = 97 ± 3% expressed VLA-4. Therefore, we anticipated that, in the baboon, the anti-VLA-4 MAb, HP1/2, would primarily affect CD14+/CD163+ cells (monocytes) from adhering to the luminal endothelium.

Anti-VLA-4 experiments.

After delivery of the Control newborns, there was an increase in expression of VCAM-1 [the ligand for the monocyte VLA-4 receptor (13)] on ductus luminal endothelial cells (Fig. 1; Tables 1 and 2), as well as an increase in the number of CD14+ and CD163+ cells (monocytes; Fig. 2; Table 2), CD3+ cells (data not shown), and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2; Table 2) adhering to the ductus luminal endothelium. We found no evidence of platelets (GP1bα+ cells), neutrophils (neutrophil elastase+ cells), or dendritic (CD83+) cells adhering to the fetal or neonatal ductus lumen (data not shown).

VCAM-1 (A–D) and eNOS (E–H) expression in cells lining the ductus lumen. Endothelial cells were detected by eNOS expression. Ductus come from fetuses (A, E) and neonates exposed to Control conditions (B, F), anti-VLA-4 (C, G), or anti-VEGF (D, H) antibodies. Small arrows (A–D) indicate brown immunostained cells. Nuclei counterstained with hematoxylin (blue). Dashed black line = internal elastic lamina (identified by phase-contrast microscopy). Horizontal bar = 50 μm.

Adherence of CD14+ (A–D) and CD8+ (E–H) cells to the ductus luminal surface. Small arrows indicate brown immunostained cells. See legend Fig. 1.

Treatment with the anti-VLA-4 MAb did not alter the expression of VCAM-1 on the luminal endothelium (Fig. 1; Tables 1 and 2) but inhibited CD14+ cells and CD163+ cells (monocytes; Fig. 2; Tables 1 and 2) from adhering to the ductus lumen. CD8+ T cells did not seem to be affected by the anti-VLA-4 MAb treatment (Fig. 2; Table 2).

Many of the genes that are essential for vascular remodeling are expressed by the ductus after postnatal constriction (Table 1) (12). Treatment with the anti-VLA-4 MAb decreased the expression of cyclooxygenase-1, IFNγ, MMP-9, PDGF-B chain, and TGFβ1 in the ductus wall (Table 1), which suggests that VLA4+/CD14+/CD163+ cell adhesion to the ductus lumen may be responsible, in part, for their expression.

The ductus of the Control newborn animals (group 1) developed the same anatomic changes that have previously been observed when postnatal constriction produces profound ductus wall hypoxia (1,2,5,12). The Control newborn ductus developed a significantly thicker neointima than the fetal ductus (Fig. 1; Table 3). The neointima was composed of an endothelial zone (filled with multiple layers of endothelial cells) and an expanding subendothelial zone (Fig. 1; Table 3) [filled with nonendothelial cells that expressed α-smooth muscle actin (data not shown)].

Treatment with the anti-VLA-4 MAb inhibited neointimal expansion (Fig. 1; Table 3). The anti-VLA-4 MAb had no effect on the postnatal increase in the number of endothelial cell layers but blocked the influx of nonendothelial cells into the subendothelial zone (Fig. 1; Table 3).

After birth, vasa vasorum invade the muscle media from the adventitia of the preterm ductus (1,5,12). Previous studies have shown that resident CD14+ and CD68+ mononuclear cells are present in the adventitia and outer muscle media of the fetal ductus (12). These mononuclear cells invade the muscle media after birth and the extent of their invasion correlates with the extent of vasa vasorum penetration into the muscle media (12). We found that treatment with the anti-VLA-4 MAb had no effect on either the postnatal invasion of CD14+, CD163+, or CD8+ cells (Fig. 3; Table 4) or the penetration of vasa vasorum into the muscle media (Table 3).

Anti-VEGF experiments.

Treatment with the neutralizing anti-VEGF MAb did not alter the expression of VCAM-1 on the luminal endothelium (Fig. 1; Table 2) but inhibited CD14+ and CD163+ cells (Fig. 2; Table 2) from adhering to the ductus lumen. CD8+ T cells did not seem to be affected by the anti-VEGF MAb treatment (Fig. 2; Table 2).

Treatment with the anti-VEGF MAb decreased the postnatal neointimal expansion by reducing the number of endothelial cell layers and by completely blocking the influx of nonendothelial cells into the subendothelial zone of the neointima (Fig. 1; Table 3).

The anti-VEGF MAb also blocked VLA-4+, CD14+, and CD163+ mononuclear cells from migrating into the outer muscle media (Fig. 3; Table 4) and inhibited vasa vasorum penetration into the muscle media (Table 3) (5). The anti-VEGF MAb did not seem to affect migration of CD8+ cells into the outer muscle media (Fig. 3; Table 4).

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms responsible for leukocyte attachment, during ductus arteriosus remodeling, differ significantly from those involved in other “injury-induced” models of vascular remodeling. In most vascular injury models, leukocyte recruitment depends on the induced expression on the endothelial cell surface of P-selectin, E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 (29–31). Leukocyte interactions with both P-selectin and ICAM-1 seem to be necessary for recruitment to occur when physiologic shear forces are present (30,32). Interactions between VCAM-1 and VLA-4 (the integrin receptor for VCAM-1) are capable of mediating leukocyte rolling and adhesion, without the need for selectins or β2 integrin/ICAM-1 interactions, but only when very low flow conditions exist (33–35).

During ductus closure, the ductus luminal endothelial cells have a very limited pattern of adhesion molecule expression (E-selectin and VCAM-1 are the only ones expressed) (12). As a result, leukocytes fail to attach in the presence of physiologic shear forces (12). VLA-4+ leukocytes can adhere to the ductus wall but only after tight constriction and loss of luminal flow have occurred (12).

We found that VLA-4 was most frequently expressed by baboon CD14+ and CD163+ cells (monocytes), less frequently by T-lymphocytes, and not at all by neutrophils. These findings help to explain why neutrophils, which normally contribute to most inflammatory conditions, are notably absent during ductus closure (see Results and Ref. 12). They also explain why the anti-VLA-4 MAb primarily blocked CD14+ and CD163+ mononuclear cells from attaching to the ductus luminal endothelium (Fig. 2; Tables 1 and 2). The VLA-4 MAb also seemed to have little effect on the postnatal migration of CD14+, CD163+, or CD8+ cells from the adventitia into the muscle media (Fig. 3; Table 4).

The present experiments demonstrate that after birth, there is increased synthesis of PDGF-B chain, MMP-9, COX-1, TGFβ, and IFNγ (Table 1) as well as smooth muscle migration into the neointima of the tightly constricted ductus arteriosus (Fig. 1; Table 3). The anti-VLA-4 MAb inhibited these events from occurring (Fig. 1; Tables 1 and 3). VLA4+/CD14+/CD163+ monocytes are the likely candidates for promoting smooth muscle cell migration into the neointima. They have the capacity to secrete proteolytic enzymes [e.g. MMP-9 (Table 1)], which are capable of degrading the extracellular matrix surrounding smooth muscle cells (9), and chemotactic substances for smooth muscle cell migration (e.g. PDGF; Table 1) (36). We hypothesize that during ductus closure, monocyte-stimulated PDGF-B production may be one of the mediators of smooth muscle cell migration, as it is in other experimental models of neointimal thickening (37).

It is possible that the anti-VLA-4 MAb could have effects on cells other than monocytes that would affect ductus arteriosus cells and gene expression; however, it is unlikely that the anti-VLA-4 MAb exerted a direct suppressive effect on smooth muscle cell migration because VLA-4 is not detected on ductus smooth muscle cells (12).

Although the expansion of the subendothelial zone of the neointima seems to depend on VLA4+/CD14+/CD163+ monocytes adhering to the ductus lumen, the proliferation and layering of endothelial cells within the neointima seem to be independent of VLA4+/CD14+/CD163+ cell attachment (Fig. 1; Table 3). Other mechanisms (e.g. VEGF) must be responsible for regulating ductus endothelial proliferation. Although VEGF is essential for luminal endothelial cell layering (Fig. 1; Table 3) (5), additional factors must contribute to the luminal endothelial cell proliferation because ductus treated with the anti-VEGF MAb still had a thicker luminal endothelial zone than fetal ductus (Table 3).

In addition to its effects on luminal endothelial cell proliferation, VEGF plays an essential role in smooth muscle cell expansion of the ductus neointima and vasa vasorum ingrowth (5). Our current studies demonstrate that VEGF is necessary for the adherence of VLA4+/CD14+/CD163+ cells (monocytes) to the ductus lumen (Fig. 2; Table 2). The VLA-4 dependent, CD14+/CD163+ cell adhesion to the ductus lumen seems to be essential for the VEGF-induced subendothelial expansion of the neointima; when VLA4+/CD14+/CD163+ cells are prevented from adhering to the ductus lumen by the MAb against VEGF, smooth muscle cell expansion of the neointima fails to occur (Fig. 1; Table 3) despite the presence of increased VEGF in the ductus wall (Table 1).

It is also intriguing to speculate that CD14+/CD163+ cell migration may play a significant role in the VEGF-induced vasa vasorum ingrowth, as vasa vasorum ingrowth was only observed in association with CD14+ and CD163+ cell (macrophage) invasion (Tables 3 and 4).

Our current findings are consistent with the hypothetical model depicted in Fig. 4. If VEGF and VLA4+/CD14+/CD163+ monocyte recruitment are central to ductus remodeling, then the current studies help to explain why tight ductus constriction and loss of luminal flow are essential for remodeling and permanent closure after birth (1,2). Decreased luminal flow has a direct effect on VEGF and VCAM-1 expression (38). Decreased flow also enables the VLA4+/CD14+/CD163+ monocytes to adhere to the ductus wall through VCAM-1/VLA-4 interactions. Once the VLA4+/CD14+/CD163+ monocytes adhere to the ductus wall, the subsequent neointimal expansion helps to permanently plug the residual lumen.

Abbreviations

- COX:

-

cyclooxygenase

- ΔCT:

-

the difference in cycle threshold between the expression of the housekeeping gene MDH and the gene of interest

- eNOS:

-

endothelial NOS

- HP1/2:

-

monoclonal antibody against VLA-4

- MDH:

-

malate dehydrogenase

- MMP-9:

-

matrix metalloproteinase-9

- VCAM-1:

-

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- VE:

-

vascular endothelial cell

- VLA-4 or CD49d:

-

α4β1 integrin mononuclear cell adhesion receptor

References

Seidner SR, Chen Y-Q, Oprysko PR, Mauray F, Tse MM, Lin E, Koch C, Clyman RI 2001 Combined prostaglandin and nitric oxide inhibition produces anatomic remodeling and closure of the ductus arteriosus in the premature newborn baboon. Pediatr Res 50: 365–373

Clyman RI, Chan CY, Mauray F, Chen YQ, Cox W, Seidner SR, Lord EM, Weiss H, Wale N, Evan SM, Koch CJ 1999 Permanent anatomic closure of the ductus arteriosus in newborn baboons: the roles of postnatal constriction, hypoxia, and gestation. Pediatr Res 45: 19–29

Levin M, McCurnin D, Seidner SR, Yoder B, Waleh N, Goldbarg S, Roman C, Liu BM, Boren J, Clyman RI 2006 Postnatal constriction, ATP depletion, and cell death in the mature and immature ductus arteriosus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R359–R364

Goldbarg S, Quinn T, Waleh N, Roman C, Liu BM, Mauray F, Clyman RI 2003 Effects of hypoxia, hypoglycemia, and muscle shortening on cell death in the sheep ductus arteriosus. Pediatr Res 54: 204–211

Clyman RI, Seidner SR, Kajino H, Roman C, Koch CJ, Ferrara N, Waleh N, Mauray F, Chen YQ, Perkett EA, Quinn T 2002 VEGF regulates remodeling during permanent anatomic closure of the ductus arteriosus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R199–R206

Echtler K, Stark K, Lorenz M, Kerstan S, Walch A, Jennen L, Rudelius M, Seidl S, Kremmer E, Emambokus NR, von Bruehl ML, Frampton J, Isermann B, Genzel-Boroviczeny O, Schreiber C, Mehilli J, Kastrati A, Schwaiger M, Shivdasani RA, Massberg S 2010 Platelets contribute to postnatal occlusion of the ductus arteriosus. Nat Med 16: 75–82

Shah NA, Hills NK, Waleh N, McCurnin D, Seidner S, Chemtob S, Clyman R 2011 Relationship between circulating platelet counts and ductus arteriosus patency after indomethacin treatment. J Pediatr 158: 919.e2–923.e2

Kevil CG, Bullard DC 1999 Roles of leukocyte/endothelial cell adhesion molecules in the pathogenesis of vasculitis. Am J Med 106: 677–687

Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A 2002 Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation 105: 1135–1143

Funayama H, Ikeda U, Takahashi M, Sakata Y, Kitagawa S, Takahashi Y, Masuyama J, Furukawa Y, Miura Y, Kano S, Matsuda M, Shimada K 1998 Human monocyte-endothelial cell interaction induces platelet-derived growth factor expression. Cardiovasc Res 37: 216–224

Abedi H, Zachary I 1995 Signalling mechanisms in the regulation of vascular cell migration. Cardiovasc Res 30: 544–556

Waleh N, Seidner S, McCurnin D, Yoder B, Liu BM, Roman C, Mauray F, Clyman RI 2005 The role of monocyte-derived cells and inflammation in baboon ductus arteriosus remodeling. Pediatr Res 57: 254–262

Springer TA 1990 Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature 346: 425–434

Keck PJ, Hauser SD, Krivi G, Sanzo K, Warren T, Feder J, Connolly DT 1989 Vascular permeability factor, an endothelial cell mitogen related to PDGF. Science 246: 1309–1312

Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ, Goeddel DV, Ferrara N 1989 Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science 246: 1306–1309

Barleon B, Sozzani S, Zhou D, Weich HA, Mantovani A, Marme D 1996 Migration of human monocytes in response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is mediated via the VEGF receptor flt-1. Blood 87: 3336–3343

Hiratsuka S, Minowa O, Kuno J, Noda T, Shibuya M 1998 Flt-1 lacking the tyrosine kinase domain is sufficient for normal development and angiogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 9349–9354

Lumsden AB, Chen C, Hughes JD, Kelly AB, Hanson SR, Harker LA 1997 Anti-VLA-4 antibody reduces intimal hyperplasia in the endarterectomized carotid artery in nonhuman primates. J Vasc Surg 26: 87–93

Huo Y, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Ley K 2000 Role of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and fibronectin connecting segment-1 in monocyte rolling and adhesion on early atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res 87: 153–159

Kling D, Fingerle J, Harlan JM, Lobb RR, Lang F 1995 Mononuclear leukocytes invade rabbit arterial intima during thickening formation via CD18-and VLA-4-dependent mechanisms and stimulate smooth muscle migration. Circ Res 77: 1121–1128

Labinaz M, Hoffert C, Pels K, Aggarwal S, Pepinsky RB, Leone D, Koteliansky V, Lobb RR, O'Brien ER 2000 Infusion of an antialpha4 integrin antibody is associated with less neoadventitial formation after balloon injury of porcine coronary arteries. Can J Cardiol 16: 187–196

Borgström P, Bourdon MA, Hillan KJ, Sriramarao P, Ferrara N 1998 Neutralizing anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody completely inhibits angiogenesis and growth of human prostate carcinoma micro tumors in vivo. Prostate 35: 1–10

Kim KJ, Li B, Winer J, Armanini M, Gillett N, Phillips HS, Ferrara N 1993 Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis suppresses tumour growth in vivo. Nature 362: 841–844

Hodara VL, Velasquillo MC, Parodi LM, Giavedoni LD 2005 Expression of CD154 by a simian immunodeficiency virus vector induces only transitory changes in rhesus macaques. J Virol 79: 4679–4690

Giavedoni LD, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N, Hodara VL, Parodi LM, Hubbard GB, Dudley DJ, McDonald TJ, Nathanielsz PW 2004 Phenotypic changes associated with advancing gestation in maternal and fetal baboon lymphocytes. J Reprod Immunol 64: 121–132

Bouayad A, Kajino H, Waleh N, Fouron JC, Andelfinger G, Varma DR, Skoll A, Vazquez A, Gobeil FJ, Clyman RI, Chemtob S 2001 Characterization of PGE2 receptors in fetal and newborn lamb ductus arteriosus. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2342–H2349

Waleh N, Kajino H, Marrache AM, Ginzinger D, Roman C, Seidner SR, Moss TJ, Fouron JC, Vazquez-Tello A, Chemtob S, Clyman RI 2004 Prostaglandin E2-mediated relaxation of the ductus arteriosus: effects of gestational age on g protein-coupled receptor expression, signaling, and vasomotor control. Circulation 110: 2326–2332

Clyman RI, Goetzman BW, Chen YQ, Mauray F, Kramer RH, Pytela R, Schnapp LM 1996 Changes in endothelial cell and smooth muscle cell integrin expression during closure of the ductus arteriosus: an immunohistochemical comparison of the fetal, preterm newborn, and full-term newborn rhesus monkey ductus. Pediatr Res 40: 198–208

Davies MJ, Gordon JL, Gearing AJ, Pigott R, Woolf N, Katz D, Kyriakopoulos A 1993 The expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, PECAM, and E-selectin in human atherosclerosis. J Pathol 171: 223–229

Dong ZM, Chapman SM, Brown AA, Frenette PS, Hynes RO, Wagner DD 1998 The combined role of P- and E-selectins in atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest 102: 145–152

Collins RG, Velji R, Guevara NV, Hicks MJ, Chan L, Beaudet AL 2000 P-Selectin or intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 deficiency substantially protects against atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Exp Med 191: 189–194

Kunkel EJ, Ley K 1996 Distinct phenotype of E-selectin-deficient mice. E-selectin is required for slow leukocyte rolling in vivo. Circ Res 79: 1196–1204

Johnston B, Issekutz TB, Kubes P 1996 The alpha 4-integrin supports leukocyte rolling and adhesion in chronically inflamed postcapillary venules in vivo. J Exp Med 183: 1995–2006

Gaboury JP, Kubes P 1994 Reductions in physiologic shear rates lead to CD11/CD18-dependent, selectin-independent leukocyte rolling in vivo. Blood 83: 345–350

Alon R, Kassner PD, Carr MW, Finger EB, Hemler ME, Springer TA 1995 The integrin VLA-4 supports tethering and rolling in flow on VCAM-1. J Cell Biol 128: 1243–1253

Martinet Y, Bitterman PB, Mornex JF, Grotendorst GR, Martin GR, Crystal RG 1986 Activated human monocytes express the c-sis proto-oncogene and release a mediator showing PDGF-like activity. Nature 319: 158–160

Jackson CL, Raines EW, Ross R, Reidy MA 1993 Role of endogenous platelet-derived growth factor in arterial smooth muscle cell migration after balloon catheter injury. Arterioscler Thromb 13: 1218–1226

Walpola PL, Gotlieb AI, Cybulsky MI, Langille BL 1995 Expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 and monocyte adherence in arteries exposed to altered shear stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 15: 2–10

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Napoleone Ferrara (Genentech) for providing us with MAb A.4.6.1. We also thank Ms. Vickie Winter, Dr. Jackie Coalson, and all the personnel at the BPD Resource Center and the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Pathology Division.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported by grants from U.S. Public Health Service [NIH grants HL46691, HL56061, HL52636 BPD Resource Center, and P51RR13986 (NCRR)] and by a gift from the Jamie and Bobby Gates Foundation. This investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant number C06 RR12087 (NCRR).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Waleh, N., Seidner, S., McCurnin, D. et al. Anatomic Closure of the Premature Patent Ductus Arteriosus: The Role of CD14+/CD163+ Mononuclear Cells and VEGF in Neointimal Mound Formation. Pediatr Res 70, 332–338 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182294471

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182294471

This article is cited by

-

Exploration of potential biochemical markers for persistence of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants at 22–27 weeks’ gestation

Pediatric Research (2019)

-

Genetic variants associated with patent ductus arteriosus in extremely preterm infants

Journal of Perinatology (2019)

-

Microarray gene expression analysis in ovine ductus arteriosus during fetal development and birth transition

Pediatric Research (2016)

-

Predictors of successful closure of patent ductus arteriosus with indomethacin

Journal of Perinatology (2015)

-

Isoprostanes as physiological mediators of transition to newborn life: novel mechanisms regulating patency of the term and preterm ductus arteriosus

Pediatric Research (2012)