Abstract

Fifty years have passed since the description of juvenile selective malabsorption of cobalamin (Cbl). Quality of life improvements have dramatically reduced the incidence of parasite-induced or nutritional Cbl deficiency. Consequently, inherited defects have become a leading cause of Cbl deficiency in children, which is not always expressed as anemia. Unfortunately, the gold standard for clinical diagnosis, the Schilling test, has increasingly become unavailable, and replacement tests are only in their infancy. Genetic testing is complicated by genetic heterogeneity and differential diagnosis. This review documents the history, research, and advances in genetics that have elucidated the causes of juvenile Cbl malabsorption. Genetic research has unearthed many cases in the past decade, mostly in Europe and North America, often among immigrants from the Middle East or North Africa. Lack of suitable clinical testing potentially leaves many patients inadequately diagnosed. The consequences of suboptimal Cbl levels for neurological development are well documented. By raising awareness, we wish to push for fast track development of better clinical tools and suitable genetic testing. Clinical awareness must include attention to ethnicity, a sensitive topic but effective for fast diagnosis. The treatment with monthly parenteral Cbl for life offers a simple and cost-effective solution once proper diagnosis is made.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin) Deficiency

In the Western world, lack of vitamin B12 alias cobalamin (Cbl) is usually because of malabsorption of this nutrient. In the following we focus on selective malabsorption, where the malabsorption affects in principle only one nutrient, Cbl. At least two such hereditary conditions are known. Recessive mutations in the gene GIF (OMIM#609342), coding for the synthesis of gastric intrinsic factor (IF), cause IF deficiency (IFD; OMIM#261000). Biallelic mutations in CUBN (OMIM#602997) or AMN (OMIM#605779), encoding the receptor for the Cbl-IF complex in the ileum, cause Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome (IGS; OMIM#261100).

Sometimes Cbl malabsorption is more-or-less selective, e.g. in general malabsorption because of gluten intolerance or tropical sprue (1), intestinal blind loops and diverticulitis with a Cbl-consuming bacterial flora (2), in pancreatic insufficiency and in poor gastric function. Inability to liberate Cbl from food is common in older adults (3). Finally, the fish tapeworm inhibits Cbl absorption by competing for the vitamin (4).

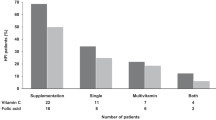

The classical manifestation of Cbl deficiency is macrocytic-megaloblastic anemia and combined degeneration of the spinal cord, but often the neurological symptoms are not observed until sought for (2,5,6). Absence of blood abnormalities may be due to high intake of folate but treatment of Cbl deficiency with folate may mask and worsen the neurological manifestations (2,5). During recent years, infertility, cardiovascular disease (homocysteine induced), and osteoporosis have been advanced as new and often the only clinical long-term signs of mild deficiency (7,8). In persons elder than 65 y, about 12% have Cbl deficiency defined with biochemical parameters (9). One cause may be failure to release food-bound Cbl with increasing age (10).

Long ago, the vitamin A or fat load test (11) revealed that Cbl deficiency in itself induces general malabsorption which also includes Cbl (Ref. 12; Fig. 1) and other nutrients (5). Apparently, the enterocytes suffer from the deficiency. The misleading failure in IF deficiency (pernicious anemia or IFD) to respond to the administration of IF in the Schilling absorption test (13) is probably also a manifestation of enterocytic malfunction. The realization that Cbl deficiency caused general malabsorption led to the finding of several new cases of IGS (14). Thus, Cbl deficiency (e.g. because of poor diet) causes reduced Cbl absorption, thereby producing a vicious circle.

Vitamin A load test during parenteral treatment with Cbl. Gradual increase in the vitamin A (fat) load test values over time in 3 patients with pernicious anemia, after parenteral treatment with Cbl. A = basal value and B = value after oral loading dose. Adapted from Gräsbeck R, Nord Med 68:1232–1234. Copyright © 1962 Nordisk Medicin, with permission.

Discovery and History of Imerslund-Gräsbeck Syndrome

This condition was described simultaneously in Norway by the pediatrician Imerslund (15) and in Finland (16). Many names have been used for the condition. The most commonly used name is Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome (IGS) (17).

The first case was an 11-y-old boy. Since the age of 2 y, he had been investigated and treated for megaloblastic anemia and proteinuria at irregular intervals. R.G. was consulted to elucidate the condition. It was found to be due to poor absorption of practically only Cbl. The case was reported at a pediatric congress in 1958 (18). At this early stage, it was already assumed that the error was located in the ileal acceptor (receptor) for vitamin B12 and that something similar affected the kidney tubules known to have many properties in common with the intestine (18,19).

The next Finnish case was found under circumstances that could be called serendipity: a student nurse in the ward where R.G. was a resident presented with identical symptoms. This strongly suggested that the two patients had the same disease or syndrome. That the condition was hereditary was suggested by the fact that the parents of the female patient were double cousins.

The two cases were thoroughly examined using up-to-date methods available to investigate Cbl deficiency because of the current research on tapeworm anemia in the department. Kidney biopsies were also performed. Suspecting that the condition represented a hitherto unknown disease entity a manuscript was drawn up. Just before its submission, it was discovered that Imerslund in Norway had collected similar cases and was preparing her dissertation. This confirmed that the syndrome existed, and we published the article (16) where the title indicated the pathogenesis “selective vitamin B12 malabsorption.” The possible common origin of the intestinal and renal tubular conditions was also pointed out.

Imerslund's (15) dissertation describing 10 cases in 6 families demonstrated that the syndrome existed; that the condition was hereditary, autosomal, and recessive; that functioning IF was secreted; and that the patients did not respond to IF (gastric juice) given together with Cbl by mouth. Despite proteinuria, kidney function was and remained good. In addition, Imerslund found anomalies in the urinary tract (double ureters and horseshoe kidney). Such findings have not been made by others. Broch, who has continued Imerslund's work in Norway, has not found such new cases either (Ref. 20 and personal communication). Combinations with other anomalies seem to be fortuitous (21).

Imerslund's dissertation did not pass “probably because too few laboratory investigations had been made” (Seip letter to Gräsbeck in 1994), which apparently means that few attempts at elucidating the pathogenetic mechanism had been made. Thus, it was not certain that the Finnish and Norwegian patients suffered from the same condition. However, using radioactive Cbl and other techniques, Imerslund and Bjørnstad (22) later made the same observations that had been made on the Finnish patients.

These first concrete observations were preceded by reports which may represent the same disease, but at the time of their publication radioactive Cbl absorption and other tests did not exist. The case reported by Najman and Brausil (23) is usually quoted. These authors suggested that their case was because of low secretion of IF. Moreover, until recently there was little awareness that an absent or inactive IF could imitate IGS (24).

Following the first reports, Lamy et al. (25) quickly reported four similar cases from France. In 1967, we were aware of 47 cases (14). At present, >300 have been published worldwide, but in many cases the diagnosis may be uncertain and some represent cases of IFD (24). In 2006, there were 27 cases from 19 families in Finland and 19 cases from 15 families in Norway (17). Today, most new cases have appeared in the Middle East, and in Europe and North America about 50% of newly diagnosed cases are detected among recent immigrants from North Africa and the Middle East (Tanner, unpublished results). In Finland and Norway, the estimated prevalence is 1:200,000 (17) but worldwide prevalence is hard to estimate. Most recently, a case from Thailand was confirmed genetically (Tanner, unpublished results).

Patient age at diagnosis varies from a few months to puberty. The patients present with diffuse symptoms such as failure to grow and thrive, pallor and fatigue, and recurrent respiratory and gastrointestinal infections. Laboratory investigations usually reveal anemia, low serum Cbl and/or proteinuria. In most cases, the neurological signs appear mild, but exceptions exist. An IGS case compound-heterozygous for two AMN mutations showed severe psychiatric instability (26). Only high-dose parenteral Cbl of 1 mg biweekly prevented behavioral relapses, whereas hematological symptoms were cured by a standard dose of 1 mg/mo. The conclusion was that the Cbl receptor may play a role at the blood-brain barrier (26). Nevertheless, Cbl deficiency may express itself only in the results of laboratory tests or after a meticulous search for clinical symptoms. Especially when the relatives of confirmed cases are examined, new cases may be discovered. Interesting possibilities are that children with monosymptomatic “benign” proteinuria or behavioral disturbances may suffer from undiagnosed IGS; therefore assay of serum Cbl of such patients seems advisable.

The combination of megaloblastic anemia and proteinuria attracted both discoverers of the syndrome. However, two of Imerslund's original cases lacked proteinuria and in 1967 two of our 19 patients lacked proteinuria (14). In a study of 13 Finnish patients (27), only 3 clearly excreted increased amounts of total protein, including albumin and smaller amounts of transferrin, light immunoglobulin chains, and alpha1 and beta2 microglobulins. Three cases excreted only modest amounts of protein and the rest had barely increased excretion levels. One explanation for the finding of more nonproteinuric patients may be that the diagnosis was based on mutational analysis, which may reveal clinically less conspicuous patients among relatives of typical patients.

Imerslund died in 1987 and her patients have been supervised since then by Broch (20). He and others, including ourselves have performed kidney biopsies on untreated and treated patients (14,28–30). In untreated patients, weak signs of membranous glomerulonephritis were observed in light microscopy. In electron microscopy, mild signs of glomerulopathy of mesangioproliferative type, increased mesangial matrix, thickening of the basal membrane, and mesangial deposits were detected. Some patients have been biopsied before and after the correction of the deficiency state, and after treatment the pathological kidney findings have usually disappeared (14). Broch recently reported to R.G. that the oldest Norwegian patient died in an accident. He had been biopsied before treatment and electron microscopic changes had been observed, but they were absent in the specimens taken at autopsy. Evidently, the changes have been because of the Cbl deficiency, which affects all cells in the body, enterocytes included. But the proteinuria persists after Cbl treatment and is probably because of the malfunction of the receptor in the kidney (31). There is general agreement that kidney function does not worsen in treated patients, some of which have been observed for more than 50 y.

Intestinal biopsies were performed at an early date and showed no pathology (14,32). Considerable efforts were expended to elucidate the structure of the Cbl-IF receptor in the ileum and its defect in IGS. For instance, it was demonstrated that the binding to the receptor required calcium ions (33,34) and later that the receptor contained two subunits (31,35). The receptor has therefore been called cubam (cubilin and amnionless) (31). Decreased urinary excretion of the receptor was found in the Finnish patients, whereas some Arab patients could even excrete increased amounts (36,37). Those patients were probably incorrectly diagnosed and suffered from lack of IF. The overall conclusion was that the disease had subsets, apparently because of different genetic errors (37). Then it was reported that the kidney receptor was identical with the intestinal one and also bound ligands other than Cbl-IF (38,39). That the receptor had several ligands was philosophically satisfying, because it seemed “luxurious” that evolution has produced one special membrane receptor for each substrate. It seems more likely that membrane transport mechanisms are variants on the same theme (40). The detailed structure of the receptor was recently described and excellently illustrated by Nielsen and Christensen (41) and Andersen et al. (42). The similarity of the kidney and ileal receptors is striking, but the two may not be completely identical. The kidney receptor mediates the reabsorption of many proteins. Uptake of nonhuman proteins in the intestine would probably elicit an immune response and be an undesirable property perhaps removed during evolution. Incidentally, porcine IF causes an immune response when given by mouth to patients (43).

The Genetic Errors

In the early 1990s, at the instigation of Albert de la Chapelle a search began to reveal the genetic error causing IGS. The error in Finnish patients was localized by linkage analysis to the short arm of chromosome 10 (44). However, attempts to identify the responsible gene failed at first. Instead, Moestrup et al. (45) cloned the gene for the intestinal Cbl receptor. They also demonstrated that the gene was localized to the locus in chromosome 10 affected by IGS (46) and the following year, mutations in the CUBN gene in the affected Finnish families were published (47).

The CUBN encoded protein named cubilin was found in membrane transport systems in the intestine, kidney, and yolk sack. It is a multiligand receptor with a molecular weight of about 460 kD when glycosylated, and it was found to be identical to the intestinal and kidney Cbl receptors. Cubilin has a peculiar structure with three domains: a 110 amino acid N-terminal stretch, followed by a cluster of 8 epidermal growth factor (EGF) regions followed by 27 CUB domains, CUB being an abbreviation for three proteins: complement components C1r/C1s, Uegf, and Bone morphogenic protein-1. The name cubilin is because of its high content of CUB domains. Although lacking a membrane anchor, cubilin adheres to the cell membrane by being bound to several transmembrane partners (41).

Linkage analysis of Imerslund's cases indicated that the affected locus mapped to chromosome 14 and not 10 (as first thought), but the critical interval did not contain any obvious candidate gene. Assuming that the affected gene was expressed in the same tissues as CUBN, the tissue expression patterns of all genes were compared with CUBN. Amnionless (AMN), essential for gastrulation in mice (48), was the top ranking candidate (49). However, previous reports showed that biallelic inactivation of AMN was lethal in mice (48) and that posed conceptual problems. Nevertheless, several different recessive mutations and functional assays ultimately demonstrated that AMN was indeed the sought after second gene causing IGS (49,50). Consequently, the Finnish and Imerslund's Norwegian cases were because of the mutations in different genes, an example of genetic heterogeneity: one phenotype—several genes.

So far, most Norwegian patients had mutations in the AMN gene and most Finnish patients had mutations in the CUBN gene but exceptions occur (Tanner, unpublished results). Cases reported from the rest of the world have had mutations in either gene (Ref. 50 and Tanner, unpublished results). The Scandinavian cases are apparently typical instances of enrichment by founder effects. In the Mediterranean region, where numerous cases have been found, rare mutations in both the CUBN and AMN genes are exposed by a high degree of consanguinity (50). However, in some cases no errors in either gene were detected. These cases were finally found to be due to mutations in the gene GIF, coding for the gastric IF after a third linkage study pinpointed its locus (24). Some of those cases had been considered to suffer from IGS because of the failure of IF to increase the absorption of radioactive Cbl in the Schilling test; this failure was apparently caused by the deficiency state of the enterocytes, leading to a mistaken diagnosis.

IGS has also been observed in dogs, first in giant schnauzers (51,52). The observed cases were mapped to a region orthologous to human chromosome 14 (53). So far, two different mutations were described in the canine AMN gene, and the phenotype is similar to that observed in humans (54). That outcome is in contrast to defects in the mouse. One of us has created Amn knock-in mice with three human IGS mutations (Tanner, unpublished results). The highly conserved sequences of human and mouse permitted the identical recreation of the human IGS mutations in the mouse. Two of these mutations (AMN c.14delG; G5fs and AMN c.683_730del48; Q228_L243del16; 50) are apparently lethal—analogous to the knock-out mouse (48)—because we have never observed any homozygous pups among over 100 offspring. Conversely, the Norwegian missense mutation AMN c.122C>T; T41I (49) is clearly viable in the homozygous mouse (Tanner, unpublished observations).

Congenital IFD

Lack of IF may be either acquired or congenital. The classic acquired case is pernicious anemia, which is caused by atrophy of the gastric mucosa with loss of secretory function (2,5). This has long been considered to be due to autoimmune destruction of the mucosa, but today it is known that Helicobacter infection may be involved (55). Many cases have antibodies against IF, thus removing the last traces of IF secreted and their presence strongly supports the diagnosis of pernicious anemia. The disease is essentially one of old people, but it occurs occasionally in children. We have ourselves described a 10-y-old girl with this disease (14) and Chanarin (2) mentions several pediatric cases.

Congenital IF deficiency (IFD) has been known since at least 1937 (56). The gastric IF gene GIF had long been postulated to be implicated in IFD (57), and the defect was expected “to reflect the usual spectrum of nonsense and missense changes” (58). In 2004, the first GIF mutation was described (59), and a larger series of cases was identified by linkage analysis (24). The clinical picture and laboratory findings do not differ from that of other juvenile Cbl deficiencies, with one exception: If the Schilling test result is low, there may be an increase if the oral radio-Cbl dose is accompanied by IF. Moreover, the patient's gastric juice may lack IF activity. Patients with IGS do not respond to IF in the Schilling test and their gastric juice contains IF. Such tests are therefore able to distinguish between the two conditions, however, a recent problem is the unavailability of radio-Cbl needed for the Schilling test (10). Immunoassay of IF is less reliable as biologically inactive (mutant) IF may still be immunoreactive. Finally, the patient may fail to respond to IF owing to the deficiency state of the enterocyte. This is probably why we detected several cases of mutations in the GIF gene among patients initially thought to suffer from IGS (24). It might be noteworthy that patients suffering from juvenile Cbl malabsorption with roots in Western Sub-Saharan Africa thus far carried a single founder mutation in GIF that may simplify diagnostic testing (60).

Practical Suggestions

Clinical picture and laboratory tests.

IGS, IFD, and other conditions are subgroups of Cbl deficiency. Therefore, before performing the tests discussed below, the presence of Cbl deficiency must be established or strongly suspected. In adults, the classical clinical symptoms are typical macrocytic anemia and neuropsychiatric signs. The tongue is often sore, and lack of gastric secretion is observed. In babies, the first signs are failure to thrive and respiratory and gastrointestinal infections but the symptoms seen in adults may also be observed when sought for. The bone marrow is typical for megaloblastic anemia. The anemia is strongly responsive to Cbl injections; there is reticulocytosis and rise in the concentration of blood cells and Hb. Such a reaction strongly indicates that Cbl deficiency was present, thus allowing diagnosis ex juvantibus. This is still a useful procedure, especially as absorption tests may suggest general malabsorption during the deficiency state. Preferably, such tests should be performed after abolishment of the deficiency. However, many adults with Cbl deficiency do not exhibit a classical clinical picture, and indications of Cbl deficiency are found only by laboratory tests, such as observing low concentrations of Cbl and high concentrations of methylmalonate or homocysteine in the serum. None of these tests have turned out to be the “gold standard,” although sensitive, they are not specific for any particular type of Cbl deficiency. At present, measuring transcobalamin (TC)-bound (active) Cbl in serum (holo-TC) seems to be accepted as the best indictor of Cbl deficiency (61,62). The finding of proteinuria should steer the thoughts to IGS. As discussed, one may also suspect that cases of monosymptomatic benign proteinuria might be due to IGS.

Nutritional lack of Cbl is frequent in developing countries. In some Western countries, Cbl deficiency is common in Vegans and abusers of nitrous oxide (which destroys the Cbl coenzymes) and especially in their nursing babies. However, most cases of Cbl deficiency are caused by poor absorption from the gastrointestinal tract, and in Europe and North America IGS and IFD today seem to be the most common causes of juvenile Cbl deficiency. Radioactive Cbl absorption tests therefore have played an important role in the diagnosis of Cbl deficiency diseases. Unfortunately, the Schilling test has almost disappeared (10).

A new nonradioactive Cbl absorption test may replace the Schilling test (63). It is based on the observation that cyano-Cbl (CNCbl) passes the intestine and enters the blood unchanged where it appears bound to TC. The patient is given three doses of CNCbl for 1 d and the TC-bound vitamin is measured. The TC-bound CNCbl then reflects Cbl absorption. At present, there is little experience of using this test. However, nonradioactive tests should be the future, for example by modernizing the assay for the Cbl-IF receptor in the urine (36,37) for diagnosis of IGS. It was shown long ago that there is IF in the urine (64), so IFD might also be diagnosed by a urinary assay.

Family History

As in other hereditary conditions, the appearance of similar cases in relatives strongly suggests that the patient has a familial condition. This is also the case if the parents are closely related. An ethnic background with roots in the Mediterranean region should also lead to the suspicion of IGS (50).

Mutational Analysis

Definite diagnosis of IGS and IFD are achieved by demonstrating biallelic mutations in one of the genes coding for the two subcomponents of the Cbl-IF receptor, CUBN or AMN (47,49,50), or the gene coding for gastric IF, GIF (24,60). Unfortunately, there is currently no single genetic test that distinguishes IGS and IFD from other Cbl deficiencies. Genetic testing is certainly the “gold standard” for clinical confirmation but genetic heterogeneity combined with the low frequency have kept commercial providers from offering genetic testing services. The screening task is daunting, as the three genes contain 87 exons covering >320 kb of genomic sequence. The coding sequences exceed 10 kb and there are >100 polymorphisms that complicate the analysis. One of us (S.M.T.) recently completed the accrual of 150 cases or sibships with suspected IGS or IFD for genetic research. However, our experience is that genetic testing is warranted only after careful clinical workup has excluded other, mostly acquired causes of deficiency (see below). Once alternative diagnoses are excluded, genetic testing is advisable because it might clarify the cause of the deficiency and demonstrate that life-long parenteral Cbl treatment is required. In addition, diagnostic results permit family counseling to prevent yet undiagnosed cases to go unnoticed. Until the lack of commercial genetic testing is resolved, we recommend that DNA samples of affected and unaffected family members are banked, so that genetic testing may resume quickly when the testing situation changes.

Diagnosis by Exclusion

This is the way the original cases of Gräsbeck et al. (16) were diagnosed. Actually, Table 1 in that article can still serve as a check list of tests to be performed. After the establishment of Cbl deficiency, Cbl absorption should be studied, traditionally with the Schilling test or possibly with the new CNCbl test (63). If the result is low, indicating poor Cbl absorption, the test is repeated by adding IF to the oral Cbl dose. If the absorption clearly increases, IF deficiency is most likely present. Whether this is because of classical pernicious anemia or IFD must then be elucidated, e.g. by testing for antibodies against IF or parietal cells, measuring hydrochloric acid, pepsin, and IF in gastric juice, or examining the gastric mucosa by gastroscopy. If the patient does not respond to IF, receptor malabsorption must be suspected, whether general or selective can be elucidated using a variety of absorption tests, blood tests indicating celiac disease, endoscopy, and examining biopsy specimens.

As stated above, the absorptive capacity of the enterocytes suffers from Cbl deficiency and the recovery may take a long time. However, after the establishment of the Cbl deficiency and replenishment of the Cbl stores by several Cbl injections, there is no hurry in establishing the exact cause of poor Cbl absorption, perhaps with the exception of intestinal blind loops, strictures and other conditions which need surgical treatment, or the presence of tapeworm and exclusion of Veganism and abuse of laughing gas in nursing mothers. As the performance of numerous tests is both expensive and time-consuming, and some informative tests are nowadays unavailable, it is advisable to keep treating the patients, especially babies, as long as health is achieved and maintained. Attempts to establish a final diagnosis can be postponed until the necessary tests become available or the patient wishes to get a more definite diagnosis.

Treatment

After reports that CNCbl may have side effects such as muscular pains following injection, worsening of tobacco amblyopia and possibly neurological conditions (65,66), hydroxocobalamin has partially replaced CNCbl in the therapy of Cbl deficiency in Europe, at least in parenteral treatment. CNCbl remains in use in the United States. (67). Oral treatment with milligram tablets has been satisfactory in pernicious anemia, but it was observed that IGS patients absorbed less of such megadoses than pernicious anemia patients (14). In adolescents and adults, we therefore suggest monthly intramuscular injections of 1 mg of hydroxocobalamin as maintenance treatment. To abolish the deficiency state, daily injections may be given for 7–10 d. Less may be given to babies, but large doses seem to have no negative side effects. One of the two original patients of R.G. reported that he had received 1 mg injections every 3 wk for over 50 y without any side effects. This routine results in fairly high serum concentrations of Cbl. Because the patients feel well long after cessation of therapy, they are tempted to stop therapy altogether. This should be strongly discouraged, especially as brain damage may ensue, notably in children (26).

Final Remarks

The clarification of the two hereditary conditions IGS and IFD has provided novel insight into cellular transport systems. The once surprising fact that the small Cbl molecule needs to attach to a big molecule (IF) to be absorbed has led to a greater understanding of intestinal absorption mechanisms. The detection of the underlying genes, whose products transport not only Cbl but many different substrates, have shed light on both intestinal and kidney function and pathology. Unfortunately, practical clinical diagnosis of these conditions has not kept pace with the corresponding development in the basic sciences. This problem is shared with other rare hereditary conditions. However, efficient maintenance treatment of both IGS and IFD results in perfect health, a gratifying result for the doctor, the patient, and the family.

Abbreviations

- Cbl:

-

cobalamin (vitamin B12)

- CNCbl:

-

cyanocobalamin

- CUB:

-

complement C1r/C1s, Uegf, Bmp1

- IF:

-

intrinsic factor

- IFD:

-

intrinsic factor deficiency

- IGS:

-

Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome

- TC:

-

transcobalamin (also called transcobalamin 2)

References

Ammoury RF, Croffie JM 2010 Malabsorptive disorders of childhood. Pediatr Rev 31: 407–415

Chanarin I 1969 The Megaloblastic Anaemias. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford,

Dali-Youcef N, Andres E 2009 An update on cobalamin deficiency in adults. QJM 102: 17–28

von Bonsdorff B 1977 Diphyllobothriasis in Man. Academic Press, London, pp 189

Chanarin I 1979 The Megaloblastic Anaemias. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford,

Chalouhi C, Faesch S, Anthoine-Milhomme MC, Fulla Y, Dulac O, Cheron G 2008 Neurological consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency and its treatment. Pediatr Emerg Care 24: 538–541

Gräsbeck R 2002 Infertility—folate, cobalamin and other micronutrients [evaluation]. Rondel. Available at http://www.rondellen.net/evaluation10_eng.htm. Accessed May 12, 2011

Herrmann W, Obeid R, Schorr H, Hubner U, Geisel J, Sand-Hill M, Ali N, Herrmann M 2009 Enhanced bone metabolism in vegetarians–the role of vitamin B12 deficiency. Clin Chem Lab Med 47: 1381–1387

Loikas S, Koskinen P, Irjala K, Lopponen M, Isoaho R, Kivela SL, Pelliniemi TT 2007 Vitamin B12 deficiency in the aged: a population-based study. Age Ageing 36: 177–183

Carmel R 2007 The disappearance of cobalamin absorption testing: a critical diagnostic loss. J Nutr 137: 2481–2484

Paterson JC, Wiggins HS 1954 An estimation of plasma vitamin A and the vitamin A absorption test. J Clin Pathol 7: 56–60

Gräsbeck R 1962 [Laboratory diagnosis of malabsorption: the vitamins.]. Nord Med 68: 1232–1234

Schilling RF 1953 Intrinsic factor studies II. The effect of gastric juice on the urinary excretion of radioactivity after oral administration of radioactive vitamin B12. J Lab Clin Med 42: 860–866

Gräsbeck R, Kvist G 1967 [Congenital and selective malabsorption of vitamin B12 with proteinuria]. Cah Coll Med Hop Paris 8: 935–944

Imerslund O 1960 Idiopathic chronic megaloblastic anemia in children. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 49: 1–115

Gräsbeck R, Gordin R, Kantero I, Kuhlbäck B 1960 Selective vitamin B12 malabsorption and proteinuria in young people. Acta Med Scand 167: 289–296

Gräsbeck R 2006 Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome (selective vitamin B12 malabsorption with proteinuria). Orphanet J Rare Dis 1: 17

Gräsbeck R, Kantero I 1958 [A case of juvenile vitamin B12 deficiency]. XII Nordiska barnläkarkongressen, Helsingfors, pp 77

Gräsbeck R, Kantero I 1959 A case of juvenile vitamin B12 deficiency. Acta Paediatr Suppl 48: 140–141

Broch H, Imerslund O, Monn E, Hovig T, Seip M 1984 Imerslund-Gräsbeck anemia. A long-term follow-up study. Acta Paediatr Scand 73: 248–253

Gräsbeck R 1997 Selective cobalamin malabsorption and the cobalamin-intrinsic factor receptor. Acta Biochim Pol 44: 725–733

Imerslund O, Bjørnstad P 1963 Familial vitamin B12 malabsorption. Acta Haematol 30: 1–7

Najman E, Brausil B 1952 [Megaloblastic anemia with relapse without gastric achylia in childhood.]. Ann Paediatr 178: 47–59

Tanner SM, Li Z, Perko JD, Oner C, Cetin M, Altay C, Yurtsever Z, David KL, Faivre L, Ismail EA, Gräsbeck R, de la Chapelle A 2005 Hereditary juvenile cobalamin deficiency caused by mutations in the intrinsic factor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 4130–4133

Lamy M, Besancon F, Loverdo A, Afifi F 1961 [Specific malabsorption of vitamin B12 proteinuria. Megaloblastic anemia of Imerslund-Najman-Gräsbeck. Study of 4 cases.]. Arch Fr Pediatr 18: 1109–1120

Luder AS, Tanner SM, de la Chapelle A, Walter JH . Amnionless (AMN) mutations in Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome may be associated with disturbed vitamin B(12) transport into the CNS. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008 Jan 7 [Epub ahead of print]

Wahlstedt-Fröberg V, Pettersson T, Aminoff M, Dugué B, Gräsbeck R 2003 Proteinuria in cubilin-deficient patients with selective vitamin B(12) malabsorption. Pediatr Nephrol 18: 417–421

Gräsbeck R, Kvist G 1967 [Congenital and selective malabsorption of vitamin B12 with proteinuria]. Munch Med Wochenschr 109: 1936–1944

Becker M, Rotthauwe HW, Weber HP, Fischbach H 1977 Selective vitamin B12 malabsorption (Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome). Studies on gastroenterological and nephrological problems. Eur J Pediatr 124: 139–153

Collan Y, Lahdevirta J, Jokinen EJ 1979 Selective vitamin B12 malabsorption with proteinuria. Renal biopsy study. Nephron 23: 297–303

Fyfe JC, Madsen M, Hojrup P, Christensen EI, Tanner SM, de la Chapelle A, He Q, Moestrup SK 2004 The functional cobalamin (vitamin B12)-intrinsic factor receptor is a novel complex of cubilin and amnionless. Blood 103: 1573–1579

Gräsbeck R 1972 Familial selective vitamin B 12 malabsorption. N Engl J Med 287: 358

Gräsbeck R, Nyberg W 1958 Inhibition of radiovitamin B12 absorption by ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) and its reversal by calcium ions. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 10: 448

Kouvonen I, Gräsbeck R 1984 The role of sialic acid in the binding of calcium ions to intrinsic factor and its intestinal receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta 797: 163–170

Kouvonen I, Gräsbeck R 1979 A simplified technique to isolate the porcine and human ileal intrinsic factor receptors and studies on their subunit structures. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 86: 358–364

Dugué B, Aminoff M, Aimone-Gastin I, Leppanen E, Gräsbeck R, Gueant JL 1998 A urinary radioisotope-binding assay to diagnose Gräsbeck-Imerslund disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 26: 21–25

Dugué B, Ismail E, Sequeira F, Thakkar J, Gräsbeck R 1999 Urinary excretion of intrinsic factor and the receptor for its cobalamin complex in Gräsbeck-Imerslund patients: the disease may have subsets. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 29: 227–230

Kozyraki R, Fyfe J, Kristiansen M, Gerdes C, Jacobsen C, Cui S, Christensen EI, Aminoff M, de la Chapelle A, Krahe R, Verroust PJ, Moestrup SK 1999 The intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 receptor, cubilin, is a high-affinity apolipoprotein A-I receptor facilitating endocytosis of high-density lipoprotein. Nat Med 5: 656–661

Kristiansen M, Kozyraki R, Jacobsen C, Nexø E, Verroust PJ, Moestrup SK 1999 Molecular dissection of the intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 receptor, cubilin, discloses regions important for membrane association and ligand binding. J Biol Chem 274: 20540–20544

Gräsbeck R, Kouvonen I 1983 The intrinsic factor and its receptor—are all membrane transport systems related?. Trends Biochem Sci 8: 203–205

Nielsen R, Christensen EI 2010 Proteinuria and events beyond the slit. Pediatr Nephrol 25: 813–822

Andersen CB, Madsen M, Storm T, Moestrup SK, Andersen GR 2010 Structural basis for receptor recognition of vitamin-B(12)-intrinsic factor complexes. Nature 464: 445–448

Lowenstein L, Cooper BA, Brunton L, Gartha S 1961 An immunologic basis for acquired resistance to oral administration of hog intrinsic factor and vitamin B12 in pernicious anemia. J Clin Invest 40: 1656–1662

Aminoff M, Tahvanainen E, Gräsbeck R, Weissenbach J, Broch H, de la Chapelle A 1995 Selective intestinal malabsorption of vitamin B12 displays recessive mendelian inheritance: assignment of a locus to chromosome 10 by linkage. Am J Hum Genet 57: 824–831

Moestrup SK, Kozyraki R, Kristiansen M, Kaysen JH, Rasmussen HH, Brault D, Pontillon F, Goda FO, Christensen EI, Hammond TG, Verroust PJ 1998 The intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 receptor and target of teratogenic antibodies is a megalin-binding peripheral membrane protein with homology to developmental proteins. J Biol Chem 273: 5235–5242

Kozyraki R, Kristiansen M, Silahtaroglu A, Hansen C, Jacobsen C, Tommerup N, Verroust PJ, Moestrup SK 1998 The human intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 receptor, cubilin: molecular characterization and chromosomal mapping of the gene to 10p within the autosomal recessive megaloblastic anemia (MGA1) region. Blood 91: 3593–3600

Aminoff M, Carter JE, Chadwick RB, Johnson C, Gräsbeck R, Abdelaal MA, Broch H, Jenner LB, Verroust PJ, Moestrup SK, de la Chapelle A, Krahe R 1999 Mutations in CUBN, encoding the intrinsic factor-vitamin B12 receptor, cubilin, cause hereditary megaloblastic anaemia 1. Nat Genet 21: 309–313

Kalantry S, Manning S, Haub O, Tomihara-Newberger C, Lee HG, Fangman J, Disteche CM, Manova K, Lacy E 2001 The amnionless gene, essential for mouse gastrulation, encodes a visceral-endoderm-specific protein with an extracellular cysteine-rich domain. Nat Genet 27: 412–416

Tanner SM, Aminoff M, Wright FA, Liyanarachchi S, Kuronen M, Saarinen A, Massika O, Mandel H, Broch H, de la Chapelle A 2003 Amnionless, essential for mouse gastrulation, is mutated in recessive hereditary megaloblastic anemia. Nat Genet 33: 426–429

Tanner SM, Li Z, Bisson R, Acar C, Oner C, Oner R, Cetin M, Abdelaal MA, Ismail EA, Lissens W, Krahe R, Broch H, Gräsbeck R, de la Chapelle A 2004 Genetically heterogeneous selective intestinal malabsorption of vitamin B12: founder effects, consanguinity, and high clinical awareness explain aggregations in Scandinavia and the Middle East. Hum Mutat 23: 327–333

Fyfe JC, Jezyk PF, Giger U, Patterson DF 1989 Inherited selective malabsorption of vitamin B12 in giant schnauzers. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 25: 533–539

Fyfe JC, Giger U, Hall CA, Jezyk PF, Klumpp SA, Levine JS, Patterson DF 1991 Inherited selective intestinal cobalamin malabsorption and cobalamin deficiency in dogs. Pediatr Res 29: 24–31

He Q, Fyfe JC, Schaffer AA, Kilkenney A, Werner P, Kirkness EF, Henthorn PS 2003 Canine Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome maps to a region orthologous to HSA14q. Mamm Genome 14: 758–764

He Q, Madsen M, Kilkenney A, Gregory B, Christensen EI, Vorum H, Hojrup P, Schaffer AA, Kirkness EF, Tanner SM, de la Chapelle A, Giger U, Moestrup SK, Fyfe JC 2005 Amnionless function is required for cubilin brush-border expression and intrinsic factor-cobalamin (vitamin B12) absorption in vivo. Blood 106: 1447–1453

Stopeck A 2000 Links between Helicobacter pylori infection, cobalamin deficiency, and pernicious anemia. Arch Intern Med 160: 1229–1230

Langmead JS, Doniach D 1937 Pernicious anaemia in an infant. Lancet 229: 1048–1049

Katz M, Lee SK, Cooper BA 1972 Vitamin B 12 malabsorption due to a biologically inert intrinsic factor. N Engl J Med 287: 425–429

Rosenblatt DS, Fenton WA 1999 Inborn errors of cobalamin metabolism. In: Banerjee R (eds) Chemistry and Biochemistry of B12. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York, pp 367–384

Yassin F, Rothenberg SP, Rao S, Gordon MM, Alpers DH, Quadros EV 2004 Identification of a 4-base deletion in the gene in inherited intrinsic factor deficiency. Blood 103: 1515–1517

Ament AE, Li Z, Sturm AC, Perko JD, Lawson S, Masterson M, Quadros EV, Tanner SM 2009 Juvenile cobalamin deficiency in individuals of African ancestry is caused by a founder mutation in the intrinsic factor gene GIF. Br J Haematol 144: 622–624

Carmel R, Green R, Rosenblatt DS, Watkins D 2003 Update on cobalamin, folate, and homocysteine. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 62–81.

Obeid R, Herrmann W 2007 Holotranscobalamin in laboratory diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency compared to total cobalamin and methylmalonic acid. Clin Chem Lab Med 45: 1746–1750

Hardlei TF, Morkbak AL, Bor MV, Bailey LB, Hvas AM, Nexø E 2010 Assessment of vitamin B(12) absorption based on the accumulation of orally administered cyanocobalamin on transcobalamin. Clin Chem 56: 432–436

Gräsbeck R, Wahlstedt V, Kouvonen I 1982 Radioimmunoassay of urinary intrinsic factor. A promising test for pernicious anaemia and gastric function. Lancet 319: 1330–1332

Freeman AG 1992 Cyanocobalamin—a case for withdrawal: discussion paper. J R Soc Med 85: 686–687

Gräsbeck R 2010 Correspondence on “Involuntary movements during vitamin B12 treatment”: was cyanocobalamin perhaps responsible?. J Child Neurol 25: 794–795

Hvas AM, Nexø E 2006 Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency—an update. Haematologica 91: 1506–1512

Acknowledgements

We thank the families and their compassionate clinicians for supporting our research over many years.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported, in part, by Grant CA16058 from the National Cancer Institute, USA, and the Magnus Ehrnrooth Foundation, Finland.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gräsbeck, R., Tanner, S. Juvenile Selective Vitamin B12 Malabsorption: 50 Years After Its Description—10 Years of Genetic Testing. Pediatr Res 70, 222–228 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182242124

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182242124

This article is cited by

-

Hereditary intrinsic factor deficiency in China caused by a novel mutation in the intrinsic factor gene—a case report

BMC Medical Genetics (2020)

-

Novel compound heterozygous mutations in AMN cause Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome in two half-sisters: a case report

BMC Medical Genetics (2015)

-

Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome in a 25-month-old Italian girl caused by a homozygous mutation in AMN

Italian Journal of Pediatrics (2013)

-

Detailed investigations of proximal tubular function in Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome

BMC Medical Genetics (2013)

-

Reversible skin hyperpigmentation in imerslund-grasbeck syndrome

Indian Pediatrics (2013)