Abstract

To evaluate whether differences in early nutritional support provided to extremely premature infants mediate the effect of critical illness on later outcomes, we examined whether nutritional support provided to “more critically ill” infants differs from that provided to “less critically ill” infants during the initial weeks of life, and if, after controlling for critical illness, that difference is associated with growth and rates of adverse outcomes. One thousand three hundred sixty-six participants in the NICHD Neonatal Research Network parenteral glutamine supplementation randomized controlled trial who were alive on day of life 7 were stratified by whether they received mechanical ventilation for the first 7 d of life. Compared with more critically ill infants, less critically ill infants received significantly more total nutritional support during each of the first 3 wk of life, had significantly faster growth velocities, less moderate/severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia, less late-onset sepsis, less death, shorter hospital stays, and better neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18–22 mo corrected age. Rates of necrotizing enterocolitis were similar. Adjusted analyses using general linear and logistic regression modeling and a formal mediation framework demonstrated that the influence of critical illness on the risk of adverse outcomes was mediated by total daily energy intake during the first week of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Recent reviews describing the growth of hospitalized neonates have demonstrated that nutritional practices are a strong influence and that there is marked practice variation within and between centers (1,2). However, because these reviews were mostly based on retrospective and prospective observational studies rather than from randomized controlled trials, the findings are subject to several limitations. For example, each infant's nutritional management was most likely influenced by the clinical team's impression of the infant's health. It is common practice for infants thought to be healthier, that is more stable or without significant metabolic imbalances or stresses, to be managed differently than infants thought to be less healthy, that is unstable or experiencing metabolic imbalances or stresses. For example, enteral feedings might be initiated earlier or advanced more rapidly from parenteral nutrition to full enteral nutrition in neonates thought to be healthier.

This project was developed as an effort to improve our understanding of factors influencing decisions about nutritional support in extremely LBW (ELBW) infants. We hypothesized that early nutritional support provided to “more critically ill” ELBW infants differed from that provided to “less critically ill” ELBW infants during the first several weeks of life. We further hypothesized that the magnitude of early nutritional support provided to ELBW infants plays a role in mediating the effects of critical illness on later outcomes such as growth, age at which nutritional milestones were achieved, and likelihood of death, short-term morbidities, and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18–22 mo corrected age.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

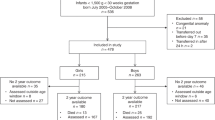

This study is a secondary analysis of data collected in the NICHD Neonatal Research Network (NRN) parenteral glutamine supplementation randomized controlled trial (3) performed between October 1999 and August 2001. The institutional review boards of all 15 participating centers approved the trial protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian of each infant. Of the 1433 ELBW infants enrolled into the glutamine trial, 1366 infants alive on day of life (DOL) 7 comprised the study population. Those infants were stratified by whether they received mechanical ventilation (MV) for the first 7 d of life or not; specifically, more critically ill infants were defined as receiving MV for the first 7 d of life, whereas less critically ill infants were defined as receiving MV for less than the first 7 d of life. This criterion was selected after the data elements available in the study dataset that would adequately reflect severity of illness and that would permit an evaluation of whether the perception of severity of illness influenced early nutritional practices were considered. Because duration of MV was collected, while other measures of illness severity, including the need for inotropic support, were not available in the dataset, MV during the first 7 d of life was chosen to define the degree of critical illness. Appropriate-for-GA (AGA) and small-for-GA (SGA) infants were evaluated separately (Fig. 1).

Neonatal information collected as part of the glutamine trial (3) included birth weight, GA at birth, gender, race, maternal information, data on nutritional support and growth, respiratory support, clinical outcomes, and treatment. Trained research nurses collected all study data using previously described definitions for clinical conditions, including selected morbidities, until discharge, transfer, death, or 120 d after birth (3). For this report, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) was defined using the NICHD/NHLBI consensus definition at 36 wk postmenstrual age (PMA) (4). Growth velocity (g/kg/d) was calculated from the date of regaining birth weight to 36 wk PMA (5). Growth measures at 36 wk PMA, including growth velocity, are presented for the subset of infants who remained hospitalized at 36 wk PMA. Early nutritional support was characterized using energy measures (kcal/kg/d) that were calculated, as previously described (6), for parenteral (total, nonprotein, and protein), enteral, and total intake, over three intervals: days 1–7, days 8–14, and days 15–21. Each of the measures was calculated as the total kcal/kg over the interval divided by the number of days the infant was hospitalized during the interval. Total fluid intake (cm3/kg/d) included parenteral and enteral intakes plus all other dextrose containing i.v. fluids and was calculated similarly (7). Although the initiation of 1.5 g/kg/d of amino acids within the first 24 h of life was encouraged by the glutamine trial (3) procedures, the trial did not specify nutritional practices, and management of nutritional support was left to the discretion of the medical staff at each participating center; large practice variations were observed between, and within, centers.

Follow-up assessments, previously described in detail (8), were performed at 18–22 mo corrected age by certified examiners and included a standardized neurological examination, Bayley Scales of Infant Development II-R [mental developmental index (MDI), psychomotor developmental index (PDI)], the Palisano Gross Motor Function examination, structured interviews, and anthropometric measurements. Neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) was defined as at least one of the following: MDI or PDI score <70, moderate or severe CP, bilateral blindness, or deafness.

Statistical analysis.

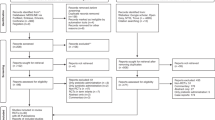

A formal mediation framework using the methods developed by Baron and Kenny (9) was used to determine whether early nutritional support mediated the association between critical illness during the first weeks of life and later growth and other outcomes (Fig. 2).

The advantage of this approach over traditional regression-based statistics is more conceptual than technical, because it allows for testing the plausibility of a presumed causal model using traditional statistical methods. We tested for mediation in this analysis to try to understand the mechanism through which critical illness in the first weeks of life may affect later growth and other outcomes. The following formal steps were used to test for mediation in our presumed mediation model:

Step 1. Establish that critical illness in the first weeks of life is associated with later growth and other outcomes.

Step 2. Establish that critical illness in the first weeks of life is associated with early nutritional support.

Step 3. Establish that early nutritional support is associated with later growth and other outcomes after controlling for critical illness in the first weeks of life.

Separate analyses were performed for AGA and SGA infants. Unadjusted analyses examining bivariate associations for steps 1 and 2 were conducted using the Wilcoxon test for continuous variables and χ2, or Fisher's exact test, where appropriate, for categorical variables. Adjusted analyses for steps 1–3 controlled for potential confounders and covariates, including birth weight, gender, race, antenatal steroids, intrapartum antibiotics, and center, using general linear models (GLMs) for continuous outcomes and logistic regression for binary outcomes (Table 1). These covariates were chosen because they were available at birth and might have contributed to the clinician's assessment of illness severity.

To assess step 1, we examined the unadjusted and adjusted association between critical illness during the first weeks of life and a host of later outcomes. Both continuous outcomes (such as growth velocity) and categorical outcomes [such as occurrence of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), NEC or death, late-onset sepsis, late-onset sepsis or death, BPD, BPD or death, NDI, and NDI or death] were examined. Next, to evaluate step 2, we examined total energy and fluid intake by degree of critical illness.

Finally, step 3 was assessed with the addition of total daily energy intake during days 1–7 of life to the adjusted models in step 1. The models in step 3 were then rerun including an interaction term between the critical illness and energy intake variables. Such a model would allow for the effect of critical illness during the first weeks of life on growth and on other outcomes to be different, depending on early nutritional practices that the infant was exposed to in hospital. For this analysis, growth velocity was analyzed as an outcome for all infants and for the subset of infants reaching 36 wk PMA, including infants transferred/discharged before 36 wk PMA, and BPD levels were collapsed for adjusted analyses into the binary categories of moderate/severe BPD versus none/mild.

All statistical analyses were conducted by the NRN Data Coordinating Center at RTI International (Research Triangle Park, NC) using SAS software (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC.). Statistical significance was indicated by a p-value <0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population separated by critical illness and appropriateness for GA are presented in Table 1. More critically ill AGA infants (MV days 1–7) weighed less at birth, had a lower GA, were more likely to be male and nonwhite, and were less likely to have received antenatal steroids than less critically ill AGA infants (MV <7 d). There were no differences between the groups in the proportion of intrapartum antibiotics given. Results were similar for SGA infants, except that there were no differences in gender or in the proportion who received antenatal steroids.

Outcome data by severity of critical illness (unadjusted analyses for step 1 in the mediation framework) are presented in Table 2. More critically ill AGA infants started enteral feedings later, and reached full feeds later, than less critically ill infants. A higher proportion of more critically ill infants had feeding interruptions for at least 24 h, but there was no difference in the incidence of NEC. More critically ill infants also experienced a higher incidence of moderate and severe BPD, intraventricular hemorrhage, and late-onset sepsis; were more likely to be treated with postnatal steroids for pulmonary disease; and were hospitalized longer than less critically ill infants. Furthermore, they grew more slowly and were smaller at 36 wk PMA when compared with less critically ill infants. Among survivors to follow-up, more critically ill AGA infants were more likely to have Bayley MDI and PDI scores <70, moderate to severe CP, and to be classified as NDI. Results were similar for SGA infants, although follow-up outcomes were not significantly different.

Results of adjusted analyses for step 1 in the mediation framework from the GLM and logistic regression model series for various outcomes are summarized in Table 3. Among AGA infants, critical illness was independently and significantly associated with slower growth velocity and with significantly increased ORs for all the tested adverse outcomes, except for NEC; late-onset sepsis was of borderline significance (p = 0.075). Thus, growth velocity in the more critically ill cohort was, on average, ∼2 g/kg/d slower compared with those in the less critically ill cohort. More critically ill infants also had almost 2.5 times higher odds for NDI or death at follow-up. Results were similar for SGA infants, except for growth velocity for survivors at 36 wk PMA, late-onset sepsis, late-onset sepsis or death, and NDI.

Step 2 in the mediation framework is established in Table 4, in which weekly energy and total fluid intakes for the first 3 wk of life are presented by severity of critical illness. Medians are included for enteral energy measures because of skewness of these data. For AGA infants, all energy measures, with the exception of parenteral protein energy over days 1–7, were significantly different by critical illness status. Specifically, compared with more critically ill AGA infants, less critically ill AGA infants received significantly more nutritional support during the first 3 wk of life. Furthermore, the transition from parenteral to enteral nutritional support was clearly evident among the less critically ill infants. Results were similar for SGA infants. Results from covariate-adjusted analyses using GLMs indicate that critical illness status remained an independent and statistically significant predictor of total energy intake even after accounting for birth weight, gender, race, antenatal steroids, intrapartum antibiotics, and center. Measures for total fluid intake variables were significantly different by severity of critical illness for DOL 1–7 for both AGA and SGA infants and for DOL 15–21 for SGA infants. Adjusted results for total fluid intake were statistically significant only for SGA infants for DOL 15–21.

Results from testing step 3 in the mediation framework, for models containing both the critical illness and energy intake variables, are summarized for AGA infants in Table 5. The effect of critical illness on the magnitude of the ORs for the tested adverse outcomes was significantly decreased once the total daily energy intake (kcal/kg/d) variable was included in the model (Table 5). These analyses indicate that critical illness during the first weeks of life and early nutritional practices are both independently associated with most of the outcomes examined, even after adjustment for several relevant covariates. For example, while the odds in favor of BPD or death increase >3-fold for more critically ill babies even after adjusting for total energy intake, an increase in total daily energy intake of only 1 kcal/kg/d was associated with a 2% decrease in the odds for BPD or death upon adjustment for critical illness and other baseline factors. Early nutrition practice as characterized by total daily energy intake was thus found to be a significant mediator of the association between critical illness during the first weeks of life and later outcomes.

In addition, although the interaction term for critical illness and total daily energy during days 1–7 of life was not significant for growth velocity, there was significant interaction between critical illness and total daily energy intake during days 1–7 of life for NDI and NDI or death. Thus, the effect of severity of critical illness on neurodevelopmental outcomes depends on the level of total daily energy during days 1–7 of life, with the effect of total daily energy on these outcomes significant for more critically ill infants only (Table 5). To illustrate the significant interaction between critical illness and total energy intake, ORs for critical illness (more versus less) are shown for varying levels of total daily energy intake, and ORs for total energy are shown separately for more and less critically ill infants.

Results from testing step 3 in the mediation framework, for models containing both the critically ill and energy intake variables, are shown for SGA infants in Table 6. Unfortunately, the sample size was not large enough to include center in the models, and no interaction terms were significant.

DISCUSSION

This retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data confirmed our hypothesis that early nutritional support provided to ELBW infants acts as a mediator of the relationship between critical illness in the first several weeks of life and later growth and other outcomes. Formal mediation steps were used to demonstrate this association. First, we established that critical illness in the first weeks of life was associated with later growth and other outcomes. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, the severity of critical illness was associated with growth, the age at which selected nutritional milestones were achieved, and rates of death, morbidities, and neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18–22 mo corrected age.

Second, we established that the degree of critical illness in the first weeks of life was associated with the amount of early nutritional support provided. Specifically, as shown in Table 4, early nutritional support provided to more critically ill ELBW infants differed from that provided to less critically ELBW infants during the first several weeks of life. Our observation is consistent with reports by other investigators who analyzed early nutritional intake data collected retrospectively in ELBW infants and described that infants, who were later to develop BPD (defined as a “requirement” for oxygen at 36 wk PMA), received significantly fewer calories and less protein in the first week of life compared with infants who did not develop BPD (10). In fact, that trend was found to have persisted for the first 5 wk of life. Furthermore, because the more critically ill infants received more fluid and less energy than the less critically ill infants during the first 7 d of life (Table 4), it is possible that the higher fluid intake contributed to the increased incidence of BPD in the more critically ill infants (7,11–13).

Third, we established that the amount of early nutritional support provided during the first weeks of life was associated with later growth and outcomes even after controlling for critical illness during the same time period. Adjusted analyses of growth and other outcomes (Tables 3, 5, and 6) demonstrated that the effect of critical illness on the risk of adverse outcomes was mediated by early energy intake. Specifically, as total daily energy intake during the first 7 d of life increased in critically ill infants, the OR of such adverse outcomes as NEC, late-onset sepsis, BPD, and NDI decreased by ∼ 2% for each 1 kcal/kg/d of total energy intake. In fact, a significant interaction term for critical illness and total daily energy was noted for NDI and NDI or death. Therefore, we believe that these results provide further evidence of the benefits derived from the practice of providing a combination of early parenteral and enteral nutritional support to critically ill infants and that these analyses demonstrate that management decisions made within the first several days of life may have long-lasting effects.

Our finding that early nutritional management mediates the influence of critical illness on the risk of adverse outcomes is consistent with a number of previous reports (6,14–22) that have demonstrated that aggressive nutritional regimes of early parenteral and enteral nutritional support can be safely provided to critically ill VLBW infants and are associated with improved growth, without increased risks adverse clinical outcomes, specifically NEC. Interestingly, a recent prospective, observational study demonstrated that a risk factor for progression from medical NEC to severe (surgical) NEC was never having received any enteral feedings (23). Inadequate energy intake has been shown to adversely affect head growth and developmental outcomes (19,20,24,25), and inadequate nutritional support has been correlated with the accumulation of significant calorie and protein deficits, which persist and are associated with poor somatic (26) and head growth (19,20). Furthermore, a recent study (22) evaluating the association of intrauterine, early neonatal, and postdischarge growth with neurodevelopmental outcomes at 5.4 y of age in 219 surviving VLBW children reported that overall, only ∼3% of the variability of the mental processing composite score was explained by growth and that contribution to neurodevelopmental outcome was only exceeded by severe intraventricular hemorrhage and prolonged MV, which accounted for 21% and 13%, respectively.

The strengths of these analyses derive from the large sample size and from the fact that all data, including those describing energy, protein, and fluid intakes, were collected prospectively. Although the age of these data may be a limitation, results from a 2006 neonatal nutrition survey (27) suggest that they are still relevant. The assignment of severity of illness based on the need for MV during the first week of life rather than a validated neonatal severity of illness score, such as the score for neonatal acute physiology (SNAP) (28), the clinical risk index for babies (CRIB) score (29), or the NEOCOSUR score (30), is a limitation. However, we believe that continuation of MV for the entire first week of life reflects the clinician's perception of an infant's severity of illness. In addition, although this project was an exploratory, secondary study of randomized, controlled trial data in which many analyses were performed, we chose not to make the level of statistical significance more stringent, but to provide the reader with p-values, which could be used to judge clinical significance.

In summary, practice decisions about early nutritional support provided to ELBW infants seem to be related to perceived severity of illness, as reflected by ventilation status at DOL 7. Significant differences in nutritional support were documented during the first week of life and persisted during the next 2 wk, even after adjusting for birth weight and other potential covariates and confounders. Early, aggressive parenteral and enteral nutritional support was associated with lower rates of death and short-term morbidities and improved growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Earlier initiation of enteral nutrition was well tolerated and was associated with an earlier achievement of full enteral nutrition, without affecting the rate of NEC. A formal mediation framework demonstrated that the influence of critical illness on the risk of adverse outcomes was mediated by total daily energy intake during the first 7 d of life.

Abbreviations

- AGA:

-

appropriate-for-GA

- BPD:

-

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- DOL:

-

day of life

- ELBW:

-

extremely LBW

- GLM:

-

general linear model

- MDI:

-

mental developmental index

- MV:

-

mechanical ventilation

- NDI:

-

neurodevelopmental impairment

- NEC:

-

necrotizing enterocolitis

- NRN:

-

Neonatal Research Network

- PDI:

-

psychomotor developmental index

- PMA:

-

postmenstrual age

- SGA:

-

small-for-GA

REFERENCES

Ehrenkranz RA 2007 Early, aggressive nutritional management for very low birth weight infants: What is the evidence?. Semin Perinatol 31: 48–55

Uhing MR, Das UG 2009 Optimizing growth in the preterm infant. Clin Perinatol 36: 165–176

Poindexter BB, Ehrenkranz RA, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, Poole WK, Oh W, Bauer CR, Papile LA, Tyson JE, Carlo WA, Laptook AR, Narendran V, Stevenson DK, Fanaroff AA, Korones SB, Shankaran S, Finer NN, Lemons JA, for the NICHD Neonatal Research Network 2004 Parenteral glutamine supplementation does not reduce the risk of mortality or late-onset sepsis in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 113: 1209–1215

Jobe AH, Bancalari E 2001 Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163: 1723–1729

Patel AL, Engstrom JL, Meier PP, Kimura RE 2005 Accuracy of methods for calculating postnatal growth velocity for extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 116: 1466–1473

Poindexter BB, Langer JC, Dusick AM, Ehrenkranz RA, for the NICHD Neonatal Research Network 2006 Early provision of parenteral amino acids in extremely low birth weight infants: relation to growth and neurodevelopmental outcome. J Pediatr 148: 300–305

Oh W, Poindexter BB, Perrits R, Lemons JA, Bauer CR, Ehrenkranz RA, Papile LA, Stoll BJ, Poole WK, Wright LL 2005 Association between fluid intake and weight loss during the first ten days of life and risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 147: 786–790

Vohr BR, Wright LL, Dusick AM, Mele L, Verter J, Steichen JJ, Simon NP, Wilson DC, Broyles S, Bauer CR, Delaney-Black V, Yolton KA, Fleisher BE, Papile L, Kaplan MD 2000 Neurodevelopmental and functional outcome of extremely-low-birth-weight (ELBW) infants. The NICHD Neonatal Research Network Follow-up Study. Pediatrics 105: 1216–1226

Baron RM, Kenny DA 1986 The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51: 1173–1182

Radmacher PG, Rafail ST, Adamkin DH 2004 Nutrition and growth in VVLBW infants with and without bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Neonatal Intensive Care 16: 22–26

Van Marter LJ, Leviton A, Allred EN, Pagano M, Kuban KC 1990 Hydration during the first days of life and the risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 116: 942–949

Marshall DD, Kotelchuck M, Young TE, Bose CL, Kruyer L, O'Shea TM, the North Carolina Neonatology Association 1999 Risk factors for chronic lung disease in the surfactant era: a North Carolina population-based study of very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 104: 1345–1350

Bell EF, Acarregui MJ 2008 Restricted versus liberal water intake for preventing morbidity and mortality in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Issue 1: CD000503

Wilson DC, Cairns P, Halliday HL, Reid M, McClure G, Dodge JA 1997 Randomised controlled trial of an aggressive nutritional regimen in sick very low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 77: F4–F11

Pauls J, Bauer K, Versmold H 1998 Postnatal body weight curves for infants below 1000 g birth weight receiving early enteral and parenteral nutrition. Eur J Pediatr 157: 416–421

Rønnestad A, Abrahamsen TG, Medbø S, Reigstad H, Lossius K, Kaaresen PI, Egeland T, Engelund IE, Irgens LM, Markestad T 2005 Late-onset septicemia in Norwegian national cohort of extremely premature infants receiving very early full human milk feeding. Pediatrics 115: e269–e276

Dinerstein A, Neito RM, Solana CL, Perez GP, Otheguy LE, Larguia AM 2006 Early and aggressive nutritional strategy (parenteral and enteral) decreases postnatal growth failure in very low birth weight infants. J Perinatol 26: 436–442

Maggio L, Cota F, Gallini F, Lauriola V, Zecca C, Romagnoli C 2007 Effects of high versus standard early protein intake on growth of extremely low birth weight infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 44: 124–129

Tan MJ, Cooke RW 2008 Improving head growth in very preterm infants-a randomized controlled trial I: neonatal outcomes. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 93: F337–F341

Tan M, Abernethy L, Cooke R 2008 Improving head growth in very preterm infants-a randomized controlled trial II: MRI and developmental outcomes in the first year. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 93: F342–F346

Stephens BE, Walden RV, Gargus RA, Tucker R, McKinley L, Mance M, Nye J, Vohr BR 2009 First-week of protein and energy intakes are associated with 18-month developmental outcomes in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 123: 1337–1343

Franz AR, Pohlandt F, Bode H, Mihatsch WA, Sander S, Kron M, Steinmacher J 2009 Intrauterine, early neonatal, and postdischarge growth and neurodevelopmental outcome at 5.4 years in extremely preterm infants after intensive neonatal nutritional support. Pediatrics 123: e101–e109

Moss RL, Kalish LA, Duggan C, Johnston P, Brandt ML, Dunn JC, Ehrenkranz RA, Jaksic T, Nobuhara K, Simpson BJ, McCarthy MC, Sylvester KG 2008 Clinical parameters do not adequately predict outcome in necrotizing enterocolitis: a multi-institutional study. J Perinatol 28: 665–674

Georgieff MK, Hoffman JS, Pereira GR, Bernbaum J, Hoffman-Williamson M 1985 Effect of neonatal caloric deprivation on head growth and 1-year developmental status in preterm infants. J Pediatr 107: 581–587

Brandt I, Sticker EJ, Lentze MJ 2003 Catch-up growth of head circumference of very low birth weight, small for gestational age preterm infants and mental development to adulthood. J Pediatr 142: 463–468

Embleton NE, Pang N, Cooke RJ 2001 Postnatal malnutrition and growth retardation: An inevitable consequence of current recommendations in preterm infants?. Pediatrics 107: 270–273

Hans DM, Pylipow M, Long JD, Thureen PJ, Georgieff MK 2006 Nutritional practices in the neonatal intensive care unit: analysis of aneonatal nutrition survey. Pediatrics 123: 51–57, 2009

Richardson DK, Gray JE, McCormick MC, Workman K, Goldmann DA 1993 Score for neonatal acute physiology: a physiologic severity index for neonatal intensive care. Pediatrics 91: 617–623

The International Neonatal Network 1993 The CRIB (clinical risk index for babies) score: a tool for assessing initial neonatal risk and comparing performance of neonatal intensive care units. Lancet 342: 193–198

Marshall G, Tapia JL, D'Apremont I, Grandi C, Barros C, Alegria A, Standen J, Panizza R, Roldan L, Musante G, Bancalari A, Bambaren E, Lacarruba J, Hubner ME, Fabres J, Decaro M, Mariani G, Kurlat I, Gonzalez A, for the Grupo Colaborativo NEOCOSUR 2005 A new score for predicting neonatal very low birth weight mortality risk in the NEOCOSUR South American Network. J Perinatol 25: 577–582

Acknowledgements

A list of investigators, who participated in the NICHD NRNs Glutamine Trial is available online as supplemental digital content for this article (http://links.lww.com/PDR/A70). We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study. Data collected at participating sites of the NICHD NRN were transmitted to RTI International, the data coordinating center for the network, which stored, managed, and analyzed the data for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development by grant support provided to the cooperating centers of the Neonatal Research Network (NRN).

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.pedresearch.org).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ehrenkranz, R., Das, A., Wrage, L. et al. Early Nutrition Mediates the Influence of Severity of Illness on Extremely LBW Infants. Pediatr Res 69, 522–529 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e318217f4f1

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e318217f4f1

This article is cited by

-

A review and guide to nutritional care of the infant with established bronchopulmonary dysplasia

Journal of Perinatology (2023)

-

The influence of nutrition on white matter development in preterm infants: a scoping review

Pediatric Research (2023)

-

Energy expenditure and body composition in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia at term age

European Journal of Pediatrics (2022)

-

NutriBrain: protocol for a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial to evaluate the effects of a nutritional product on brain integrity in preterm infants

BMC Pediatrics (2021)

-

Human induced pluripotent stem cell derived hepatocytes provide insights on parenteral nutrition associated cholestasis in the immature liver

Scientific Reports (2021)