Abstract

We have shown that cerebellar injury in the premature infant is followed by significant growth impairment of the contralateral cerebral hemisphere evident as early as term adjusted age. In this study, we hypothesize that this remote growth restriction is region specific in the cerebrum. In a prospectively enrolled cohort of 38 expreterm infants with isolated cerebellar injury by neonatal MRI, we performed follow-up volumetric MRI studies at a mean postnatal age of 35.5 ± 13.8 mo. We measured volumes of cortical and subcortical gray matter, and cerebral white matter within eight parcellated regions for each cerebral hemisphere. Unilateral cerebellar injury (n = 24) was associated with significantly smaller volumes of cortical gray and cerebral white matter in the following regions of the contralateral (versus ipsilateral) cerebral hemisphere: dorsolateral prefrontal, premotor (PM), sensorimotor, and midtemporal regions (p < 0.001 for all except midtemporal cortical gray, p = 0.01), as well as subcortical gray matter in the PM region (p < 0.001). Conversely, in cases of bilateral cerebellar injury (n = 14), there was no significant interhemispheric difference in tissue volumes for any of the cerebral regions studied. These findings suggest that regional cerebral growth impairment results from interruption of cerebellocerebral connectivity and loss of neuronal activation critical for development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Brain injury in the extremely premature infant occurs most frequently within the first days after birth (1), preceding major developmental events in the cerebral hemispheres that normally occur during the third trimester of gestation. It is increasingly clear that long-term neurodevelopmental consequences of extreme prematurity are mediated not only by acute destructive events but also by disruptive effects on subsequent brain development in regions adjacent to and remote from the original injury (2). Normal brain development proceeds along a sequence of precisely programmed events. Normal structural and functional development of the cerebral cortex and its connectivity are critically dependent on appropriate neuroaxonal activation. In the normal mature brain, numerous neural circuits, mostly closed loop, connect a spectrum of motor and nonmotor regions of the cerebral cortex with the cerebellum. Development and consolidation of infrastructure critical for these circuits begin during late fetal and early postnatal life.

Cerebellar injury is a previously under-recognized form of prematurity-related brain injury (3–5) occurring most commonly among extremely premature infants born before 28-wk gestation, thus before the onset of the third trimester (3). Cerebellar injury in the premature infant is associated with impaired growth of the uninjured contralateral cerebral hemisphere, with significant impairment evident as early as the end of the third trimester, i.e. at term equivalent age (6). The regional specificity of such crossed cerebellocerebral diaschisis has not been studied in the immature developing brain, and the regional specificity of these remote growth effects in the cerebrum after prematurity-related cerebellar injury remains unknown.

In this study of a cohort of children with prematurity-related brain injury confined to one or both cerebellar hemispheres, we used a quantitative, three-dimensional volumetric MRI technique, with regional parcellation and tissue segmentation, to test several hypotheses: that unilateral cerebellar injury in the premature infant would be associated with decreased volumetric growth in specific cerebellar projection areas of the contralateral cerebral hemisphere; that both cerebral gray and white matter volumes would be reduced in these regions; and that bilateral cerebellar injury would be associated with symmetric volume reduction in these same supratentorial regions.

METHODS

This prospective study identified all preterm infants born before 32-wk gestation between January 1998 and December 2005 diagnosed with isolated cerebellar injury by cranial ultrasound studies in the newborn period. We confirmed the presence and extent of cerebellar parenchymal injury, as well as the absence of supratentorial parenchymal abnormalities by cranial ultrasound and early postnatal MRI studies performed on all infants at a mean age of 44.2 ± 5.2-wk postconceptional age (early MRI). The cerebellar lesions were all encephaloclastic; no dysgenetic lesions were identified. The susceptibility-weighted MRI studies in all cases showed blood products in/around the cerebellar lesions. We excluded all infants with supratentorial parenchymal injury, grade III intraventricular hemorrhage, or posthemorrhagic ventriculomegaly. Sixteen children were excluded for these reasons.

We also excluded preterm infants with dysmorphic features or chromosomal anomalies suggestive of a genetic syndrome, metabolic disorders, or central nervous system infections. The study was approved by the Children's Hospital Boston Committee on Clinical Investigation. After obtaining written informed consent, follow-up quantitative brain MRI studies were performed.

MRI data acquisition methods.

All studies were performed on a 1.5 Tesla General Electric Signa System MR scanner (Milwaukee, WI), using an eight-channel phased array head coil. MRI sequences included conventional, spin echo T1-weighted, fast spin echo T2-weighted images, multiplanar gradient recalled echo susceptibility sensitive sequence, three-dimensional Fourier-transform spoiled gradient recalled (SPGR) sequence (1.5-mm coronal slices; flip angle: 45 degrees; repetition time: 35 ms; echo time: 3 ms; field of view: 20 cm; matrix: 256 × 256; 116 slices), and double-echo (proton density and T2-weighted) spin-echo sequence (3-mm axial slices; repetition time: 5000 ms; echo times: 50 ms; field of view: 20 cm; matrix: 256 × 256, interleaved acquisition; 58 slices).

MRI Data Analysis Methods

Qualitative MRI analyses.

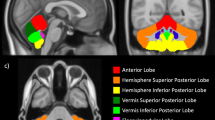

The MRI findings were analyzed qualitatively by an experienced neuroradiologist (R.L.R.) blinded to the infants' perinatal history, previous MRI findings, and outcome data, using conventional, spin echo T1-weighted, and fast spin echo T2-weighted MRI scans. Cerebellar parenchymal lesions were categorized as unilateral or bilateral (Fig. 1).

Quantitative volumetric MRI analysis.

Postimage analysis was undertaken on Linux Workstations. A six-parameter linear transformation algorithm was applied to align the T2-weighted images to the SPGR images for tissue classification. Each MRI study was first registered to Talairach space (7); the brain was then automatically segmented into three tissue classes: gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid, using a previously validated probabilistic classification method (8). Subcortical gray matter was delineated manually using similar procedures described by Srinivasan et al. (9) (Fig. 2). To obtain separate measurements for cerebral volumes [i.e. cerebral gray matter, cerebral white matter, and total cerebral volume (cerebral gray matter volume + cerebral white matter volume)], cerebellar volumes [i.e. cerebellar gray matter volumes, cerebellar white matter volumes, and total cerebellar volume (cerebellar gray matter volume + cerebellar white matter volume)] were subtracted from total brain volume by manually outlining the cerebellum onto the ICBM-152 template (10) (using in-house developed Display software); the invert of the nonlinear registration was then applied to transform the cerebellar mask onto the subject's native space. Tissue segmentation was performed by a single operator (N.G.). Intrarater reliability for tissue segmentation, evaluated in a blinded manner using 10 segmentations each from five subjects, showed the following intraclass coefficients for segmentation of different tissue types: cerebrospinal fluid 0.95; cerebral gray matter 0.97; cerebral white matter 0.93; subcortical gray matter 0.96; total cerebellar volume 0.96; cerebellar gray matter 0.95; and cerebellar white matter 0.93.

Each brain image was registered into Talairach space by interactive rotation and translation in the left/right, anterior/posterior, and inferior/superior directions. The cerebellum was divided into right and left hemispheres by selecting the midsagittal plane to ensure that the vermis was divided with a consistent approach for all MRI studies (6). Regional comparisons in the cerebrum were made using a previously described and validated Talairach scheme (11). Each cerebral hemisphere was further divided into eight anatomical regions (Fig. 3): dorsolateral prefrontal (DLPF), orbitofrontal (OF), premotor (PM), subgenual (SG), sensorimotor (SM), midtemporal (MT), parietooccipital (PO), and inferior occipital (IO) using the axial plane passing through the anterior commissure and posterior commissure (AC-PC) line and three limiting coronal planes. The parcellation scheme was performed four times on the MRI data of seven individual subjects by a single operator (N.G.). Intrarater reliability for regional volumes calculated using intraclass correlations averaged 0.94 and ranged between 0.89 and 0.98.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software. Descriptive statistics were performed to characterize the clinical features of the population and to describe their cerebellar, brainstem, and cerebral growth. Subjects were categorized into two groups, unilateral cerebellar injury and bilateral cerebellar injury, based on clinical interpretation of the MRI studies. To assess the difference between unilateral and contralateral cerebral volumes, a cerebellar volume difference score was obtained as the difference between total left (cerebellar gray matter volume + cerebellar white matter volume) and total right (cerebellar gray matter volume + cerebellar white matter volume) cerebellar hemisphere volumes. A three-way ANOVA model with repeated measures on two factors was carried out to analyze the data. The ANOVA models were analyzed using SAS repeated measures mixed modeling procedure and included two within-subject effects region (eight levels), cerebral growth side (ipsilateral versus contralateral), and between-subject factor cerebellar growth impairment group (unilateral versus bilateral). Variance Components covariance structure was defined allowing covariances to vary due to the subject (cerebellar group), region, and cerebral growth side.

Separate multiple regression analyses of clinical and demographic factors potentially associated with cerebral volume were carried out for gray matter, subcortical gray matter, and white matter volumes for right and left cerebral hemispheres, and for total brain volume. Residual plots were inspected to verify linearity, normality, and homoscedasticity assumptions. Collinearity was assessed based on tolerance, variation of inflation, and Eigen values. In addition, Jackknife residuals and Cook's D statistics were used to identify potential outliers and influential observations. Model diagnostic (adjusted R2 and Mallow's Cp), heuristic (stepwise selection), information criteria (Akaike Information Criterion), and Schwarz Bayesian Criteria statistical techniques were compared with select final regression models.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics.

Forty-five expreterm children born 1998–2005 met our inclusion criteria. Four subjects died in the early postnatal period and three were lost to follow-up. The remaining 38 subjects (93% recruitment) underwent follow-up MRI studies. The study cohort consisted of 26 boys and 12 girls born at mean gestational age 26.3 ± 1.9 wk. Follow-up MRI studies were performed at mean postnatal age 35.5 ± 13.8 mo. On the basis of MRI findings, subjects were categorized into unilateral (n = 24) and bilateral (n = 14) cerebellar injury groups. Table 1 summarizes the descriptive characteristics of the cohort.

Relationship between cerebellar injury groups (unilateral versus bilateral) and regional cerebral volumes.

Mixed models of repeated measures for cerebral gray matter and white matter volumes demonstrated similar results. For all models, a three-way interaction (group-by-region-by-side) was statistically significant along with the main effects (p < 0.001). Further, Tukey-Kramer's post hoc analysis of simple effects of the interaction term revealed a consistent trend of the results for cortical gray matter and white matter volumes (Fig. 4). In the unilateral cerebellar injury group, cortical gray matter volumes were significantly smaller in the contralateral DLPF, PM, SM (p < 0.001 for each), and MT (p = 0.01) regions compared with volumes in these regions of the ipsilateral cerebral hemisphere; there were no significant differences in the volumes of OF, SG, IO, and PO regions between the cerebral hemispheres (Fig. 4). The effects of unilateral cerebellar injury on regional cerebral white matter volumes were similar, with significantly lower white matter volumes in the contralateral DLPF, PM, SM, and MT regions (p < 0.001 for each). Conversely, after bilateral cerebellar injury, there was no significant difference between the ipsilateral and contralateral gray matter or white matter volumes in any of these cerebral hemispheric regions.

Cerebellar injury groups and ipsilateral vs. contralateral regional cerebral gray and white matter volumes in eight regions. A, Unilateral cerebellar injury, gray matter regions. B, Unilateral cerebellar injury, white matter regions. C, Bilateral cerebellar injury, gray matter regions. D, Bilateral cerebellar injury, white matter regions. Dark boxes indicate ipsilateral volumes, white boxes indicate contralateral volumes. *indicate findings that were statistically significant. The p values are based on the Tukey-Kramer's post hoc analysis of simple effects of the interaction term (cerebellar growth impairment group-by-region-by-cerebral growth side).

Subcortical gray matter volume mixed model showed statistically significant two-way interactions (group-by-region, group-by-side, and region-by-side). Tukey-Kramer's post hoc analysis showed statistically significant lower contralateral subcortical gray matter volumes compared with the ipsilateral volumes after unilateral cerebellar injury (p = 0.001). Similarly, contralateral cerebral volumes were statistically significantly lower compared with the ipsilateral volumes in the PM region (p < 0.001). Table 2 summarizes the results of the least square means difference estimates with corresponding Tukey-Kramer adjusted 95% CI for all three ANOVA models described earlier.

Supplemental statistical analysis was carried out for the cerebrospinal fluid volumes. Again the three-way interaction (group by region by side) was shown to be statistically significant (p < 0.001). Additional Tukey-Kramer's post hoc analysis of simple effects of the interaction term revealed that within the unilateral cerebellar injury group, average contralateral cerebrospinal fluid volumes were significantly larger (p < 0.0001) compared with ipsilateral volumes in the DLPF, PM, SM, and MT regions. For children with bilateral cerebellar injury, there was no statistical difference in any of parcellated region between ipsilateral and contralateral sides.

Multivariate analyses.

Predictor variables assessed in the initial model were gestational age at birth, gender, chronological age at MRI, and cerebellar left and right hemisphere volumes. Results of the multivariate analysis are summarized in Table 3. Predictors included in the final models explained 52–87% of the variation in total cortical gray matter (left and right), total white matter (left and right), total subcortical gray matter (left and right), and total cerebral volumes. In all 7 final models presented in Table 3, age at MRI and cerebellar volumes were found to be key indicator variables. All selected independent variables were positively associated with the corresponding contralateral cerebral volume outcome measure.

DISCUSSION

Our earlier studies in premature infants focused on third trimester brain development using quantitative MRI at term-adjusted age (6,12). These studies showed that prematurity was associated with impaired cerebellar volumetric growth, even in the absence of obvious brain injury (12), and that direct injury to the cerebellum impaired cerebellar growth and also growth of the uninjured contralateral cerebral hemisphere (6). This study extends our observations of the developmental effects of prematurity-related cerebellar injury to a mean age of 3 y and measures contralateral regional cerebral tissue volumes using advanced MRI parcellation and tissue segmentation techniques. Gray and white matter volumes of the contralateral cerebral hemisphere were significantly decreased in specific target regions for cerebellar projection pathways, supporting the notion that regional cerebral growth impairment is due to interruption of cerebellocerebral pathways with loss of neuronal activation critical for development in these cerebral regions. There were only two independent predictors of regional cerebral hemispheric volume. First, the volume of the contralateral cerebellar hemisphere, presumably reflecting the degree of initial injury, independently predicted cerebral volume in the affected regions. Second, the significant association between age at follow-up quantitative MRI suggests that the growth-restricting impact of cerebellar injury in these regions persisted over the age range studied, with neither catch-up nor parallel growth; this notion must, however, be qualified by the cross-sectional nature of the study.

Transtentorial diaschisis occurs when primary injury to the cerebrum or cerebellum results in secondary functional impairment in contralateral transtentorial projection targets of the primary region of injury (13–16). This phenomenon is best described after primary cerebral injury (usually stroke) in the adult (17), although a number of reports have described cerebral effects after primary cerebellar injury (18–20). Perfusion studies after cerebellar stroke in adults have shown decreased regional activation in contralateral frontal (predominantly PM) (21) and parietal cortices (20,22,23). Functional MRI studies in normal subjects have shown connectivity between the cerebellum and the prefrontal and parietal lobes of the cerebrum (24). Transneuronal viral vectors in nonhuman primates have delineated projection pathways of the cerebellum to the cerebral cortex (25,26). Pathways from the dentate pass through the contralateral thalamus to the frontal cortex (prefrontal, PM, and primary motor) and to the posterior parietal cortex (25,26), whereas a pathway from the vermis and fastigial nuclei (the limbic cerebellum) passes via the hypothalamus to the cerebral limbic centers (27). The topography of these normal cerebral target regions of cerebellar projection pathways underlies the distribution of decreased cerebral activation after cerebellar injury. In the mature brain, such functional deactivation may evolve to structural changes, presumably due to synaptic, dendritic, or neuronal loss after withdrawal of neurotrophic stimuli normally maintained by afferent input from the contralateral cerebellum. Understanding of the cerebral effects of prematurity-related cerebellar injury remains limited (6,28). Over the third trimester, increase in functional neural activation is a fundamental stimulus for the normal development of brain connectivity. It is reasonable to assume that cerebellar injury occurring during this critical development period, and resulting deafferentation to specific regions of the cerebral cortex, would result in atrophy of existing structures and in impaired subsequent cortical development in these regions.

In this cohort of children with prematurity-related cerebellar injury, volumetric MRI showed significantly reduced cerebral gray matter and white matter volumes in the DLPF, PM, MT, and SM regions of the cerebral hemisphere contralateral to the primary cerebellar injury. These regions are known projection areas of the contralateral cerebellar hemisphere. Bilateral cerebellar injury was not associated with significant asymmetry in the regional volumes of the cerebral hemispheres. A major cerebellocerebral pathway passes through the contralateral thalamus en route to the cerebral cortex. It is therefore of interest that our measures of subcortical gray matter volume in the contralateral PM region were also significantly reduced. Conversely, in our subjects there was no significant volume difference between the OF, SG, IO, and PO regions of the cerebral hemispheres. Of these areas, the posterior parietal region is a major projection area of the cerebellum. The reason for the lack of asymmetry between the PO regions following unilateral cerebellar injury is not clear. One possible explanation is that the large size of the PO parcel makes it insensitive to smaller regions of growth restriction. This study used an established parcellation technique previously used by Peterson et al. (11) in expremature children to compare regional cerebral development between children born prematurely or at term. Ex-premature subjects demonstrated region specific but symmetric volume reductions in the SM, MT, PM, and PO regions of premature infants compared with term-born infants (11).

We postulate that the region-specific growth impairment in the contralateral cerebral hemispheres after prematurity-related cerebellar injury results from disruption of transtentorial neural systems with failure of activation-dependent trophic stimulation. An important difference in crossed cerebellocerebral diaschisis between the adult brain and that of the expremature infants described here is that the cerebellar injury and loss of remote activation in the contralateral cerebral hemisphere occurs during a period of cerebral cortical development before critical reciprocal pathways for normal motor and nonmotor learning are firmly established. We propose that these mechanisms form the basis for the striking long-term motor, social, behavioral, cognitive, and language impairments described in survivors of extreme prematurity and cerebellar injury (4,5,29). Specific relationships between regional cerebral growth impairment and the spectrum of neurodevelopmental disabilities (4,29) after prematurity-related cerebellar injury remain poorly understood and are the focus of ongoing studies.

This study has several potential limitations. Although we selected subjects with injury isolated to the cerebellum on the basis of early life conventional MRI studies, it is possible that subtle supratentorial parenchymal injury below the resolution of current clinical MRI went undetected. Although our study is unable to prove a causal relationship, several features are supportive of such a relationship. First, the cerebral growth impairment is regionally specific in projection areas of the contralateral injured cerebellar hemisphere. Second, early life MRI studies in all cases showed no evidence of injury in these (or any other) cerebral parenchymal regions. Several potential limitations regarding the parcellation technique warrant mention. First, operator inconsistency is possible when placing images into standard Talairach orientation; however, our intraobserver reliability measures were all consistently >0.89. Second, the subcortical gray matter volume parcel used in our study does not differentiate between the basal ganglia and thalamic nuclei. Third, in this study, we did not parcellate the cerebellum; future studies will explore the more specific functional topography of the developing cerebellum (30). Certain regions of the parcellation scheme used in this study, such as the PO region, are large and may lack sensitivity for isolating regional cerebral effects of cerebellar injury. Future studies may overcome this limitation by using newer techniques such as voxel-based morphometry. Finally, the functional significance of our structural measurements remains to be determined. Follow-up studies are currently underway to examine the impact of impaired regional cerebral growth on neurodevelopmental outcome.

In conclusion, this study of the developmental consequences of prematurity-related cerebellar injury provides the first in vivo evidence of region-specific growth impairment in known target projection areas of the normal cerebellum on the contralateral cerebral hemisphere. These findings support the important role of disturbed development following injury to the premature brain, a notion that is increasingly recognized as an important determinant of neurodevelopmental outcome. The role of this regional cerebral growth impairment in the high prevalence of pervasive neurodevelopmental dysfunction (4,29) experienced by these children is currently under investigation.

Abbreviations

- DLPF:

-

dorsolateral prefrontal

- IO:

-

inferior occipital

- OF:

-

orbitofrontal

- PM:

-

premotor

- SG:

-

subgenual

- SM:

-

sensorimotor

- MT:

-

midtemporal

- PO:

-

parietooccipital

References

Volpe JJ 2008 Intracranial hemorrhage: Germinal matrix-intraventricular hemorrhage of the premature infant. Neurology of the Newborn. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 517–588

Volpe JJ 2009 Brain injury in premature infants: a complex amalgam of destructive and developmental disturbances. Lancet Neurol 8: 110–124

Limperopoulos C, Benson CB, Bassan H, Disalvo DN, Kinnamon DD, Moore M, Ringer SA, Volpe JJ, du Plessis AJ 2005 Cerebellar hemorrhage in the preterm infant: ultrasonographic findings and risk factors. Pediatrics 116: 717–724

Messerschmidt A, Fuiko R, Prayer D, Brugger PC, Boltshauser E, Zoder G, Sterniste W, Weber M, Birnbacher R 2008 Disrupted cerebellar development in preterm infants is associated with impaired neurodevelopmental outcome. Eur J Pediatr 167: 1141–1147

Bodensteiner JB, Johnsen SD 2005 Cerebellar injury in the extremely premature infant: newly recognized but relatively common outcome. J Child Neurol 20: 139–142

Limperopoulos C, Soul JS, Haidar H, Huppi PS, Bassan H, Warfield SK, Robertson RL, Moore M, Akins P, Volpe JJ, du Plessis AJ 2005 Impaired trophic interactions between the cerebellum and the cerebrum among preterm infants. Pediatrics 116: 844–850

Collins DL, Neelin P, Peters TM, Evans AC 1994 Automatic 3D intersubject registration of MR volumetric data in standardized Talairach space. J Comput Assist Tomogr 18: 192–205

Zijdenbos AP, Dawant BM 1994 Brain segmentation and white matter lesion detection in MR images. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 22: 401–465

Srinivasan L, Dutta R, Counsell SJ, Allsop JM, Boardman JP, Rutherford MA, Edwards AD 2007 Quantification of deep gray matter in preterm infants at term-equivalent age using manual volumetry of 3-tesla magnetic resonance images. Pediatrics 119: 759–765

Evans AC, Collins DL, Mills SR, Brown ED, Kelly RL, Peters TM 1993 3D statistical neuroanatomical models from 305 MRI volumes. Proc IEEE Nucl Sci Symp Med Imaging Conf 3: 1813–1817

Peterson BS, Vohr B, Staib LH, Cannistraci CJ, Dolberg A, Schneider KC, Katz KH, Westerveld M, Sparrow S, Anderson AW, Duncan CC, Makuch RW, Gore JC, Ment LR 2000 Regional brain volume abnormalities and long-term cognitive outcome in preterm infants. JAMA 284: 1939–1947

Limperopoulos C, Soul JS, Gauvreau K, Huppi PS, Warfield SK, Bassan H, Robertson RL, Volpe JJ, du Plessis AJ 2005 Late gestation cerebellar growth is rapid and impeded by premature birth. Pediatrics 115: 688–695

Pantano P, Baron JC, Samson Y, Bousser MG, Derouesne C, Comar D 1986 Crossed cerebellar diaschisis. Further studies. Brain 109: 677–694

Niimura K, Chugani DC, Muzik O, Chugani HT 1999 Cerebellar reorganization following cortical injury in humans: effects of lesion size and age. Neurology 52: 792–797

Miyazawa N, Toyama K, Arbab AS, Koizumi K, Arai T, Nukui H 2001 Evaluation of crossed cerebellar diaschisis in 30 patients with major cerebral artery occlusion by means of quantitative I-123 IMP SPECT. Ann Nucl Med 15: 513–519

Komaba Y, Mishina M, Utsumi K, Katayama Y, Kobayashi S, Mori O 2004 Crossed cerebellar diaschisis in patients with cortical infarction: logistic regression analysis to control for confounding effects. Stroke 35: 472–476

Yamauchi H, Fukuyama H, Nagahama Y, Nishizawa S, Konishi J 1999 Uncoupling of oxygen and glucose metabolism in persistent crossed cerebellar diaschisis. Stroke 30: 1424–1428

Sonmezoglu K, Sperling B, Henriksen T, Tfelt-Hansen P, Lassen NA 1993 Reduced contralateral hemispheric flow measured by SPECT in cerebellar lesions: crossed cerebral diaschisis. Acta Neurol Scand 87: 275–280

Gomez Beldarrain M, Garcia-Monco JC, Quintana JM, Llorens V, Rodeno E 1997 Diaschisis and neuropsychological performance after cerebellar stroke. Eur Neurol 37: 82–89

Komaba Y, Osono E, Kitamura S, Katayama Y 2000 Crossed cerebellocerebral diaschisis in patients with cerebellar stroke. Acta Neurol Scand 101: 8–12

Broich K, Hartmann A, Biersack HJ, Horn R 1987 Crossed cerebello-cerebral diaschisis in a patient with cerebellar infarction. Neurosci Lett 83: 7–12

Hausen HS, Lachmann EA, Nagler W 1997 Cerebral diaschisis following cerebellar hemorrhage. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 78: 546–549

Sagiuchi T, Ishii K, Aoki Y, Kan S, Utsuki S, Tanaka R, Fujii K, Hayakawa K 2001 Bilateral crossed cerebello-cerebral diaschisis and mutism after surgery for cerebellar medulloblastoma. Ann Nucl Med 15: 157–160

Allen G, McColl R, Barnard H, Ringe WK, Fleckenstein J, Cullum CM 2005 Magnetic resonance imaging of cerebellar-prefrontal and cerebellar-parietal functional connectivity. Neuroimage 28: 39–48

Middleton FA, Strick PL 2001 Cerebellar projections to the prefrontal cortex of the primate. J Neurosci 21: 700–712

Kelly RM, Strick PL 2003 Cerebellar loops with motor cortex and prefrontal cortex of a nonhuman primate. J Neurosci 23: 8432–8444

Stoodley CJ, Schmahmann JD 2009 Functional topography in the human cerebellum: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage 44: 489–501

Rollins NK, Wen TS, Dominguez R 1995 Crossed cerebellar atrophy in children: a neurologic sequela of extreme prematurity. Pediatr Radiol 25: S20–S25

Limperopoulos C, Bassan H, Gauvreau K, Robertson RL Jr, Sullivan NR, Benson CB, Avery L, Stewart J, Soul JS, Ringer SA, Volpe JJ, duPlessis AJ 2007 Does cerebellar injury in premature infants contribute to the high prevalence of long-term cognitive, learning, and behavioral disability in survivors?. Pediatrics 120: 584–593

Schmahmann JD 2004 Disorders of the cerebellum: ataxia, dysmetria of thought, and the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 16: 367–378

Acknowledgements

We thank Shaye Moore for assistance with manuscript preparation and the children and families for their participation in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported by the Hearst Foundation, the LifeBridge Fund, the Caroline Levine Foundation, the Trust Family Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (NINDS K24NS057568, A.J.P.), and the Canada Research Chairs Program, Canada Research Chair in Brain and Development Tier 2 (C.L.).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Limperopoulos, C., Chilingaryan, G., Guizard, N. et al. Cerebellar Injury in the Premature Infant Is Associated With Impaired Growth of Specific Cerebral Regions. Pediatr Res 68, 145–150 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181e1d032

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181e1d032

This article is cited by

-

Cerebellar contributions to a brainwide network for flexible behavior in mice

Communications Biology (2023)

-

Glutamatergic cerebellar neurons differentially contribute to the acquisition of motor and social behaviors

Nature Communications (2023)

-

The cerebellum is causally involved in episodic memory under aging

GeroScience (2023)

-

The shifting role of the cerebellum in executive, emotional and social processing across the lifespan

Behavioral and Brain Functions (2022)

-

Cerebellar volumes and language functions in school-aged children born very preterm

Pediatric Research (2021)