Abstract

Values of IGF-I after extraction, its binding proteins, and the high affinity GH-binding protein (BP) are not well established in pediatric patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM). We report data for IGF-I, IGFBP-1 and -3, and GHBP in 92 Spanish children with IDDM, separated according to pubertal stage: prepubertal (n = 49); pubertal onset(n = 17); mid-puberty (n = 17), and complete puberty(n = 9), as well as to metabolic control (HbA1 <9% or≥9%). IGF-I levels in IDDM patients increased throughout development(p < 0.001), but were diminished at every developmental stage when compared with matched control subjects. IGF-I concentrations showed a negative correlation with the degree of metabolic control, in particular during the prepubertal stage of development. A negative correlation(r = -0.22; p < 0.005) between IGF-I concentrations and HbA1 was found. Serum IGFBP-1 levels diminish during maturation in diabetic patients (p < 0.001). However, IDDM patients have significantly higher levels of IGFBP-1 than control subjects at every stage of development, and IDDM patients with inadequate metabolic control exhibit even greater differences when compared with matched control subjects. A positive correlation (r = 0.22; p < 0.005) between IGFBP-1 concentrations and HbA1 was found. IGFBP-3 serum levels were similar to those observed in normal subjects, and no correlation was observed in relation to the metabolic control. In IDDM patients, GHBP levels change significantly during maturation, as they do in normal control subjects; however, significantly lower GHBP levels were found in prepubertal and pubertal IDDM patients. GHBP levels were independent of metabolic control, although a tendency toward lower levels of GHBP was seen when HbA1 levels increased. We suggest that a partial GH resistance syndrome exists in IDDM patients, and this may be related to the metabolic control. Hence, the biochemical markers measured here may be of value in evaluating the smaller pubertal growth spurt in diabetic patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

IDDM is the most frequent chronic disease of childhood. The incidence in Spain has been recently evaluated to be 11.3 per 100,000 children below 15 y of age(1). Although during the early years of experience with insulin therapy severe abnormalities in growth were common in children with IDDM, probably due to low levels of insulin and poor metabolic control of the disease, the introduction of new therapeutic procedures and more intensive control of the diabetes has resulted in better metabolic control(2), and, consequently, lower incidences of growth abnormalities have been described.

The augmentation in knowledge about IGF-I and IGFBP, as well as the identification and characterization of the GHBP of high affinity and low capacity, has improved the clinical approach to the analysis of growth in patients with IDDM. The IGF, and in particular IGF-I, play an important role in the regulation, differentiation, and proliferation of a number of cell types, acting as a major growth regulator in humans, as well as in the regulation of the carbohydrate metabolism(3). Although IGF-I has been shown to be a good biochemical parameter for the evaluation of normal growth and growth disorders, the precise physiologic function of IGF-II remains unclear. The IGF circulate in serum bound to IGFBP. During the last few years, new biochemical parameters, including the IGFBP(4) and the GHBP(5), have become available to the clinician to better evaluate normal growth and growth disorders during childhood.

Although its physiologic role remains unclear, IGFBP-1 is suggested to be the endocrine element secreted by the liver under insulin regulation to modulate IGF-I activity in humans(6). IGFBP-1 levels vary markedly during the day, and this variation is related to the metabolic status, with an inverse relationship existing between IGFBP-1 and insulin levels(7). The identification and characterization of the GHBP(8–10) have provided additional biochemical markers to better understand the physiology of GH and growth disorders.

The information available regarding IGF-I, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-3, and GHBP plasma levels in patients with IDDM is scarce and confusing. Hence, we still ignore whether IGFBP and GHBP levels can be of interest as biologic markers of growth abnormalities in IDDM. Furthermore, how the metabolic control of the disease can influence these biologic markers remains to be clarified.

The present report examines in detail the IGF-I, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-3, and GHBP plasma levels in Spanish children and adolescents with IDDM. In addition, this study provides information regarding possible modifications in these parameters according to the metabolic control of the disease and furnishes relevant information about the growth patterns of these patients during the evolution of the disease.

METHODS

Subjects. The study population included 92 Spanish children and adolescents (1-18 y old) with a mean disease evolution of 3 ± 0.4 y and 600 matched control subjects divided into four groups according to the Tanner stages(11): 1) prepubertal (Tanner I), 49 patients with IDDM and 252 control subjects; 2) puberty onset(Tanner II), 17 patients with IDDM and 82 control subjects; 3) mid-puberty (Tanner III + IV), 17 patients with IDDM and 187 control subjects; and 4) complete puberty (Tanner V), 9 patients with IDDM and 79 control subjects. The characteristics of the control group have been previously reported(12). The Tanner stages were evaluated by at least two investigators according to breast development in girls and to genital development in boys (a volume greater than 4 mL was considered as onset of puberty). Every control subject consulted the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at the Hospital Niño Jesús for presumed endocrinopathies and were found to be normal. The height of all control subjects was ±1 SD according to the Spanish standards(13). The growth velocity was evaluated in all control subjects for a period of 6 mo and was found to be ±1 SD by using the Spanish standards. All of the control subjects showed a bone age similar to their chronologic age. All of the diabetic patients were diagnosed in our hospital after first consulting for symptoms of IDDM (polydipsia, polyuria, astenia, anorexia, and hyperglycemia with or without ketosis). Blood samples for the present study were obtained from these subjects during one of their regular biochemical follow-ups. At this time, the patients had been treated for IDDM for a period of at least 1 y. All of the samples for IGF-I, IGFBP-1, IFGBP-3, and GHBP were extracted between 0800 and 0900 h with the patient fasting.

The BMI was calculated as weight [(kg)/height (m)2]. The BMI SD scores were based upon normative data from Spanish children(13). All subjects were informed of the purpose of the study. They gave consent as prescribed by the local human ethics committee.

Serum measurements. Fasting blood samples were taken in all of the patients between 0800 and 0900 h. Serum IGF-I was performed by RIA(Nichols Laboratories, San Juan Capistrano, CA), after acid ethanol extraction. IGFBP-3 was performed by RIA (Mediagnost GmbH, Germany) directly on serum. IGFBP-1 was determined by ELISA (Medix Biochemica, Finland) on nonextracted serum. Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 4.9 and 8.9% for IGF-I, 3.56 and 6.05% for IGFBP-3, and 4.6 and 9.8% for IGFBP-1, respectively.

GHBP determinations were performed (Endocrine Sciences, Calabasas Hill, CA) with a RIA by incubating patient serum with radiolabeled human GH and the MAb 263 in the presence or absence of GH. The GH receptor is bound to this antibody and to labeled human GH to form a trimolecular complex (anti-GH receptor GHBP-125I-human GH). The intraassay and the interassay coefficients of variations were 5.6 and 9.5%, respectively.

HbA1 concentrations were measured by HPLC. HbA1 plasma levels up to 9% were arbitrarily considered as acceptable metabolic control. In contrast, HbA1 plasma levels >9% were considered as poor metabolic control. The proportion of IDDM patients with HbA1 values less than 9% and greater than or equal to 9% is reflected in Table 1.

Statistics. Differences between the experimental groups were determined by performing a one-way ANOVA, followed by Scheffé'sF test. Significance was chosen as p < 0.05. Correlations between different parameters were determined by linear regression analyses.

RESULTS

Height and growth velocity. The mean height and growth velocity of patients with IDDM was found to be in the normal range for their stage of development (Table 2).

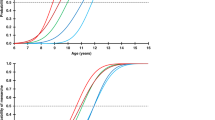

IGF-I serum levels. As shown in Figure 1A, serum IGF-I levels change significantly throughout maturation in normal boys and girls (p < 0.001, by ANOVA)(12). Serum IGF-I levels in patients with IDDM were significantly lower during the prepubertal, mid-pubertal, and pubertal stages when compared with stage-matched control subjects (Table 3). Although there was a tendency for IGF-I to be lower at the beginning of puberty, it was not significant. When data were analyzed according to metabolic control, the diabetic patients with inadequate metabolic control showed a tendency toward lower IGF-I levels than the diabetic patients with adequate metabolic control (Fig. 1A). This tendency was only statistically significant (p < 0.001) in the prepubertal period. Furthermore, IGF-I levels showed a negative correlation (r = -0.22) with HbA1 plasma levels (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). Although IGF-I plasma levels in patients with IDDM increased throughout development, a significant increase was found only between prepubertal subjects and patients starting puberty (p < 0.001). The same difference was demonstrated in control subjects.

IGFBP-1 serum levels. Serum IGFBP-1 levels in normal boys and girls decline significantly with maturation (p < 0.001, by ANOVA)(12). Although in IDDM patients serum IGFBP-1 tended to diminish with maturation, a significant difference was seen only between the prepubertal stage and the beginning of puberty (p < 0.001). Serum IGFBP-1 levels in patients with IDDM were significantly higher when compared with control subjects at every stage of development (Table 3).

When data were analyzed according to the degree of metabolic control (Fig. 1B), we observed that diabetic patients with inadequate control (HbA1 ≥9%) exhibited significantly higher serum IGFBP-1 levels than control subjects at every stage of development. In contrast, this phenomenon was not observed in IDDM patients with acceptable metabolic control (HbA1 <9%), with the exception of patients who had completed puberty. When comparing serum IGFBP-1 levels in patients with IDDM, only prepubertal patients with inadequate metabolic control exhibited significantly higher levels than IDDM subjects with adequate control. In addition, when the data were analyzed according to the metabolic control, a positive correlation was found (r = 0.22) between HbA1 and IGFBP-1 plasma levels (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2B).

IGFBP-3 serum levels. Patients with IDDM, both male and female, exhibit a similar pattern of serum IGFBP-3 levels at every stage of development (Table 3) to that seen in normal subjects. In addition, these values were completely independent of the degree of metabolic control (Fig. 1C). In patients with IDDM, no correlation was found between HbA1 and IGFBP-3 plasma levels (Fig. 2C). A significant linear relationship between IGFBP-3 and IGF-I plasma levels has been observed in normal children(12). This relationship is maintained in IDDM patients (Fig. 3).

Serum IGFBP-3 levels in both normal and IDDM boys follows a pattern similar to that of serum IGF-I levels. A significant increase is observed between Tanner stages I-III, no significant differences are seen between Tanner stages III and IV, and a significant decline ocurrs between Tanner stages IV and V(ANOVA, p < 0.001). In contrast, serum IGFBP-3 levels in normal and IDDM girls shows a significant increase between Tanner stages I and II; no significant differences are seen between Tanner stages II and III, but there is a significant increase between Tanner stages III and IV and a significant decline between Tanner stages IV and V (ANOVA, p < 0.001).

GHBP serum levels. Serum GHBP levels in normal boys and girls show a significant decline (ANOVA, p < 0.001) between prepubertal and pubertal subjects and no significant differences between pubertal and adult subjects(12). In contrast, no significant maturational changes were seen among patients with IDDM. Interestingly, serum GHBP levels were significantly lower in IDDM patients, not only prepubertal, but also at the beginning of puberty (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, when serum GHBP values were analyzed according to the degree of metabolic control among patients with IDDM, there were no significant differences found between patients with inadequate or adequate metabolic control (Fig. 4B). However, upon regression analysis a nonsignificant tendency to exhibit lower GHBP levels was observed among the diabetic patients with higher HbA1 plasma levels (Fig. 2D).

BMI and serum IGF-I, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-3, and GHBP. Although in normal subjects there are significant positive correlations between BMI(expressed as the SD) and serum IGF-I, IGFBP-3, and GHBP and a negative correlation between BMI and serum IGFBP-1(12), in diabetic subjects no significant correlations, positive or negative, were found when comparing BMI with any of the values studied (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we provide data for IGF-I, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-3, and GHBP in Spanish children and adolescents with IDDM, separated according to appropriate or inadequate metabolic control, as well as to pubertal stage. Because we have previously shown that these parameters are good biochemical markers for growth and nutrition(12), and it is known that growth and final height can be altered in these patients with chronic disease, we sought to determine whether these biochemical markers are modified in patients with IDDM. As opposed to other studies, these biochemical parameters were measured simultaneously, as well as the mean height and growth velocity of these diabetic patients. We have found changes in IGF-I, IGFBP-1, and GHBP serum concentrations in diabetic patients, and some of these factors are dependent on the state of metabolic control.

Although at the moment of diagnosis of the disease IDDM patients often exhibit normal height, and some authors have reported that they may even be relatively taller than control subjects(14), growth impairment may occur right after the beginning of the disease. However, growth abnormalities often become more apparent during puberty due, at least in part, to a reduced growth spurt(14). In our study, the mean height and growth velocity of patients with IDDM was found to be in the normal range during all stages of development, although growth velocity in pubertal patients was slightly below the average when compared with our nondiabetic population. This suggests that patients with IDDM may lose some centimeters off of their final height. In our study, as in others, the final height in IDDM patients is in the normal range, but slightly below the mean for control subjects and the genetic target of these subjects(15). Abnormal growth hormone activity, with regard to its ability to normally produce IGF-I, has been suggested. This alteration, still not properly understood, is not linked to a diminution in GH secretion, because a number of studies have shown the presence of increased serum GH levels in patients with IDDM(16). Spontaneous GH secretion is generally increased, with modulation occurring in the amplitude of the secretory bursts and sometimes also in the number of peaks(17). Therefore, we hypothesize, as discussed below, that a type of GH insensitivity syndrome may occur in diabetic patients which leads to a slightly reduced final height.

Serum concentrations of IGF-I in the diabetic population have been reported previously. Results are contradictory, because IGF-I has been shown to be in the normal range, diminished, or elevated(18). Nevertheless, although high IGF-I serum concentrations have been described in diabetic patients with advanced retinopathy(19), most of the authors have shown a diminution in IGF-I serum levels in 50-90% of diabetic patients. In our study, IGF-I serum levels are diminished in patients with IDDM at every stage of development. As in nondiabetic subjects, IGF-I serum levels increase when puberty starts(20); however, they remain significantly lower when compared with control subjects. These data further emphasize the hypothesis that diabetic patients exhibit a type of GH insensitivity syndrome. Furthermore, the relationship between IGF-I serum levels and glycemic control is also controversial. Indeed, although some authors suggest that there is no relationship between these parameters(21), others, in contrast, show data with an inverse relationship between these parameters(22). Our data suggest that IGF-I serum levels are related to the degree of metabolic control, as shown in Figure 2A, in particular during the prepubertal period when significantly lower levels of IGF-I serum concentrations can be seen in IDDM patients with inadequate metabolic control(HbA1 ≥9%) when compared with those IDDM patients with acceptable metabolic control (Fig. 1A). The explanation of this phenomenon remains unknown.

Serum concentrations of IGFBP-1 are significantly higher in IDDM patients at every stage of development. This abnormal elevation, plus the correlation with HbA1 levels observed in our patients (Fig. 2B), as well as by others(23), suggests that these patients have insufficient insulin levels and, therefore, inadequate metabolic control. Indeed, insulin inhibits IGFBP-1 gene expression(24). As in control subjects, IGFBP-1 levels diminish with maturation, although they remain significantly higher than in control subjects at every stage of development. Although we do not know the biologic significance of these abnormal IGFBP-1 levels, we can speculate that high concentrations of IGFBP-1 could contribute to diminishing the biologic activity of IGF-I(25) and increase the biologic repercussions of the GH insensitivity syndrome. Hence, it could be hypothesized that low levels of IGF-I and diminished IGF-I activity could be the principal elements contributing to the GH hypersecretion in patients with IDDM. This hypothesis is in agreement with that proposed by Dunger(15) and is supported by recent data from Cheethamet al.(26) showing that restoration of normal concentrations of IGF-I by using recombinant IGF-I has led to consistent reductions in GH secretion.

It has been demonstrated that puberty influences insulin resistance(27), both in normal subjects and in diabetic patients, with increased GH levels being implicated in this phenomenon. In effect, during the night, maximal secretion of GH and relatively low levels of insulin, particularly during the second half of the night(28), can contribute to the inadequate control of IDDM generating the “down phenomenon” that is most common during mid-puberty(29). It is possible that the nocturnal increase of IGFBP-1 levels in normal subjects plays a role in preventing nocturnal hypoglycemia(30); however, in diabetic patients, very high IGFBP-1 levels would further inhibit the already low IGF-I levels, increasing the hyperglycemia and contributing to the inadequate control of the disease(31).

Normal serum concentrations of IGFBP-3 follow the same pattern as IGF-I serum concentrations with a significant increase in IGFBP-3 serum levels at puberty(12, 32). Bach et al.(23) have previously reported low IGFBP-3 levels in pubertal patients with IDDM, as well as the lack of the typical increase in IGFBP-3 levels during puberty. In contrast, our data showed no differences in IGFBP-3 between diabetic patients and control subjects (Fig. 1C). These results are in agreement with those of Brismar et al.(33). Hence, we cannot speculate about the possible biologic value of IGFBP-3 serum levels in diabetic patients because we found normal values at every stage of development. The fact that IGFBP-3 levels are normal in diabetic patients suggests that, if a resistance to GH exists, it is only partial because IGFBP-3 is under GH control, either directly or indirectly.

Little information is available in the literature regarding GHBP serum levels in patients with IDDM, but most reports have shown low GHBP levels(34–37). In our study, diabetic patients exhibited significantly lower GHBP serum levels than control subjects, particularly during the prepubertal period and at the start of pubertal development. We did not find any significant relationship between GHBP serum levels and the degree of metabolic control in diabetic patients; however, patients with inappropriate metabolic control showed a tendency toward lower GHBP plasma levels. In addition, we did not find any correlation between GHBP serum levels and BMI among diabetic patients, which is in agreement with data previously reported by Clayton et al.(37). Although we do not have a clear explanation, it is possible that either the disease modifies this relationship or that most of our patients show a BMI very near to the mean. In addition, it is interesting to note that diabetic patients do not exhibit a significant decline in GHBP serum levels during mid-puberty (Tanner stages II-III) as we demonstrated in control subjects(12). The effects of puberty on GHBP serum levels are controversial, but our data and that of others(38) suggest that GHBP levels in diabetic subjects do not have the modifications during development that are seen in the control population.

The pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in the alterations observed in the GH axis of diabetic patients remain unknown. Low GHBP serum levels in diabetic patients, in addition to the presence of elevated GH levels and low IGF-I serum concentrations, is in agreement with the existence of a certain degree of GH resistance(38). Low IGF-I levels could explain the hypersecretion of GH and the observed abnormal responses to pharmacologic stimuli(39), although another pathophysiologic IDDM-specific mechanism could be involved. Indeed, antibodies toγ-aminobutyric acid are frequently present in diabetic patients which may suggest that hypothalamic abnormalities in the regulation of neurotransmitters could modify the balance between GH-releasing hormone and somatostatin(39). In conclusion, this study provides data for IGF-I, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-3, and GHBP in Spanish children and adolescents with IDDM. These patients exhibit significantly low IGF-I serum concentrations, significantly high IGFBP-1 levels, normal IGFBP-3 concentrations, and significantly lower GHBP serum levels. The hypothesis that a partial GH resistance syndrome is present in patients with IDDM is considered. The modifications in these parameters could be related, at least in part, to the degree of metabolic control of the disease and are probably implicated in the growth abnormalities, in particular the diminution in the growth spurt during puberty, that these patients suffer, as well as in the development of micro- and macrovascular complications. Hence, these results further emphasize the necessity of better control of this disease to permit normal growth in these patients, as well as to possibly delay the chronic complications seen in IDDM.

Abbreviations

- IDDM:

-

insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

- BP:

-

binding protein

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

References

Serrano Rios M, Moy CS, Martin Serrano R, Minuesa A, Tomas ME, Zarandieta G, Herrera J 1990 Incidence of type I diabetes mellitus in subjects 0:14 years of age in the Comunidad of Madrid, Spain. Diabetologia 33: 422–425.

Amiel SA, Sherwin RS, Simonson DC, Lauritano AA, Tamborlane WV 1986 Impaired insulin action in puberty: a contributing factor to poor glycaemic control in adolescents with diabetes. N Engl J Med 315: 215–219.

Baxter RC, Martin JL 1989 Binding proteins for the insulin-like growth factors: structure, regulation and function. Prog Growth Factor Res 1: 49–68.

Cohen P, Fielder PJ, Hasegawa Y, Frish H, Giudice LC, Rosenfeld RG 1991 Clinical aspects of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins. Acta Endocrinol 124: 74–85.

Daughaday WH, Trivedi B 1991 Clinical aspects of growth hormone binding proteins. Acta Endocrinol 124: 27–32.

Holly JMP 1991 The physiological role of IGFBP-1. Acta Endocrinol 124: 55–62.

Holly JMP, Biddlecombe RA, Dunger DB 1988 Circadian variation of GH-independent IGF-binding protein in diabetes mellitus and its relationship to insulin. A new role for insulin?. Clin Endocrinol 29: 667–675.

Baumann G, Stolar MW, Amburn K, Barsano CP, DeVries BC 1986 A specific growth hormone-binding protein in human plasma: initial characterization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 62: 134–141.

Herington AC, Ymer S, Stevenson J 1986 Identification and characterization of specific binding proteins for growth hormone in normal human sera. J Clin Invest 77: 1817–1823.

Baumann G, Shaw MA 1990 A second, lower affinity growth hormone binding protein in human plasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 70: 680–686.

Tanner JM 1962 Growth and Adolescence, 2nd Ed. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford

Argente J, Barrios V, Pozo J, Muñoz MT, Hervás F, Stene M, Hernández M 1993 Normative data for insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), IGF-binding proteins, and growth hormone-binding protein in a healthy Spanish pediatric population: age and sex related changes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 77: 1522–1528.

Hernández M, Castellet J, Narvaíza JL, Rincón JM, Ruiz I, Sanchez E, Sobradillo B, Zurimendi A 1988 In: Hernández M, Fundación F. Orbegozo (eds) Curvas y tablas de crecimiento. Editorial Garsi, Madrid

Vanelli M, Fanti A, Adinolfi B, Ghizzoni L 1992 Clinical data regarding the growth of diabetic children. Horm Res 37( suppl): 65:669.

Dunger DB 1992 Diabetes in puberty. Arch Dis Child 67: 569–573.

Edge JA, Dunger DB, Matthews DR, Gilbert JP, Smith CP 1990 Increased overnight growth hormone concentrations in diabetes compared with normal adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 71: 1356–1362.

Nieves-Ribera F, Rogol A, Veldhuis JD, Branscon DK, Martha PM, Clarke WL 1993 Alterations in growth hormone secretion and clearance in adolescent boys with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 77: 638–643.

Amiel SA, Sherwin RS, Hintz RL, Gertner JM, Press CM, Tamborlane WV 1984 Effect of diabetes and its control on insulin-like factors in the young subject with type I diabetes. Diabetes 33: 1175–1179.

Merimee TJ, Zapf J, Froesch ER 1983 Insulin-like growth factors. Studies in diabetics with and without retinopathy. N Engl J Med 309: 527–530.

Juul A, Bang P, Hertel NT, Main K, Dalgaard P, Jorgensen K, Muller J, Hall K, Skakkebaek NE 1994 Serum insulin-like growth factor-I in 1030 healthy children, adolescents, and adults: relation to age, sex, stage of puberty, testicular size, and body mass index. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78: 744:75752

Taylor AM, Dunger DB, Grant DB, Preece MA 1988 Somatomedin-C/IGF-I measured by RIA and somatomedin bioactivity in adolescents with insulin dependent diabetes compared with puberty matched controls. Diabetes Res 9: 177–181.

Blethen SL, Sargeant DT, Whitlow MG, Santiago JV 1981 Effect of pubertal stage and recent blood glucose control on plasma somatomedin C in children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 30: 868–872.

Bach JA, Baxter RC, Werther G 1991 Abnormal regulation of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 73: 964–968.

Baxter RC 1993 Circulating binding proteins for the insulin like growth factors. Trends Endocrinol Metab 4: 91–96.

Taylor AM, Dunger DB, Preece MA, Holly JMP, Smith CP, Waas JAH, Patel S, Tate VE 1990 The growth hormone independent insulin-like growth factor-I binding protein BP-28 is associated with serum insulin-like growth factor-1 inhibitory bioactivity in adolescent insulin-dependent diabetics. Clin Endocrinol 32: 229–239.

Cheetham TD, Jones J, Taylor AM, Holly JP, Matthews DR, Dunger DB 1993 The effects of recombinant insulin-like growth factor-I administration on growth hormone levels and insulin requirements in adolescents with type I (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 36: 678–681.

Amiel SA, Caprio S, Sherwin RS, Pleeve G, Haymond MW, Tamborlane WV 1991 Insulin resistance of puberty: a defect restricted to peripheral glucose metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72: 277–282.

Edge JA, Matthews DR, Dunger DB 1990 Failure of current insulin-regimens to meet the overnight requirements of adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes Res 15: 109:11112

Beaufrere B, Beylot M, Metz C, Ruitton A, Francois R, Riou JP, Mornex R . 1988 Down phenomenon in type I (insulin dependent) diabetic adolescents: influence of nocturnal growth hormone secretion. Diabetologia 31 607: 611

Lee PD, Conover CA, Powell DR 1993 Regulation and function of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 204: 4–29.

Rieu M, Binoux M 1985 Serum levels of insulin-like growth factors (IGF) and IGF binding protein in insulin-dependent diabetes during an episode of severe metabolic descompensation and the recovery phase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 60: 781–785.

Barrios V, Argente J 1993 Aspectos metodológicos y utilidad diagnóstica de la proteina transportadora de los factores de crecimiento similares a la insulina-3 (IGFBP-3). Endocrinologia 40: 133–136.

Brismar K, Fernquist-Forbes E, Wahen J, Hall K 1994 Effect of insulin on the hepatic production of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), IGFBP-3 and IGF-I in insulin-dependent diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 79: 872–878.

Menon RK, Arslanian S, May B, Cutfield WS, Sperling MA 1992 Diminished growth hormone-binding protein in children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 74: 934–938.

Massa G, Dooms L, Bouillon R, Vanderschueren-Lodewey CKX M 1993 Serum levels of growth hormone binding-protein and insulin like growth factor I in children. Diabetologia 36: 239:243

Holl RW, Setgler B, Scherbaum WA, Heinze E 1993 The serum growth hormone-binding protein is reduced in young patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 76: 165–167.

Clayton KL, Holly JM, Carlsson LMS, Jones J, Cheetham TD, Taylor AM, Dunger DB 1994 Loss of the normal relationships between growth hormone, growth hormone-binding protein and insulin-like growth factor-I in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Clin Endocrinol 41: 517–524.

Baumann G, Shaw MA, Amburn K 1989 Regulation of plasma growth hormone-binding proteins in health and disease. Metabolism 38: 683–689.

Giustina A, Wehrenberg WB 1994 Growth hormone neuroregulation in diabetes mellitus. Trends Endocrinol Metab 5: 73–78.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Julie A. Chowen for the critical review of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Supported by Fundación Endocrinología y Nutrición.

This work was presented in part at the 36th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology in Sevilla, Spain, and reported in abstract from (Endocrinología 1993;40:26).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muñoz, M., Barrios, V., Pozo, J. et al. Insulin-Like Growth Factor I, Its Binding Proteins 1 and 3, and Growth Hormone-Binding Protein in Children and Adolescents with Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus: Clinical Implications. Pediatr Res 39, 992–998 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199606000-00011

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199606000-00011

This article is cited by

-

Growth Hormone and Counterregulation in the Pathogenesis of Diabetes

Current Diabetes Reports (2022)

-

Renal effects of growth hormone in health and in kidney disease

Pediatric Nephrology (2021)

-

Insulin does not rescue cortical and trabecular bone loss in type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats

The Journal of Physiological Sciences (2018)

-

Derangement of calcium metabolism in diabetes mellitus: negative outcome from the synergy between impaired bone turnover and intestinal calcium absorption

The Journal of Physiological Sciences (2017)