Abstract

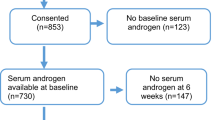

The relationships between serum level of testosterone (T) and prostate cancer (PCa) are complex. The present study evaluated whether presence of PCa alters serum T levels. Subjects were 125 patients with clinically localized PCa treated using radical prostatectomy (RP), for whom pretreatment T levels were recorded. We investigated clinical and pathological factors such as pretreatment serum T level, age, pretreatment prostate-specific antigen, Gleason score and pathological stage. Serum T and human luteinizing hormone (LH) levels before and after RP were then compared in 118 of the 125 patients. Mean pretreatment T level was significantly higher in patients with organ-confined PCa (pT2; 4.03±1.50 ng ml−1) than in patients with nonorgan-confined cancer (pT3; 3.42±1.06 ng ml−1; P=0.0438). No association existed between pretreatment serum T level and pathological Gleason score. After RP, serum T level (5.60±1.90 ng ml−1) was significantly elevated compared to preoperative level (3.89±1.43 ng ml−1; P<0.0001). In parallel, significant increases were seen in postoperative serum LH level (6.86±3.64 ng ml−1) compared to preoperative level (5.11±2.47 ng ml−1; P=0.0001). In contrast, differences in serum T levels according to pathological stage disappeared postoperatively (P=0.5513). Significant increases in serum T and LH levels were seen after RP, compared to preoperative levels in parallel. This study suggests that serum T levels are altered by the presence of PCa, supporting the possibility that PCa may inhibit serum T levels with negative feedback in the hypothalamic–pituitary axis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 4 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $64.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Chan JM, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL . What causes prostate cancer? A brief summary of the epidemiology. Semin Cancer Biol 1998; 8: 263–273.

Ekman P . Genetic and environmental factors in prostate cancer genesis: identifying high-risk cohorts. Eur Urol 1999; 35: 362–369.

Freedland SJ, Isaacs WB, Platz EA, Terris MK, Aronson WJ, Amling CL et al. Prostate size and risk of high-grade, advanced prostate cancer and biochemical progression after radical prostatectomy: a search database study. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 7546–7554.

Chen SS, Chen KK, Lin AT, Chang YH, Wu HH, Chang LS . The correlation between pretreatment serum hormone levels and treatment outcome for patients with prostatic cancer and bony metastasis. BJU Int 2002; 89: 710.

Morgentaler A . Testosterone deficiency and prostate cancer: emerging recognition of an important and troubling relationship. Eur Urol 2007; 52: 623–625.

Stattin P, Lumme S, Tenkanen L, Alfthan H, Jellum E, Hallmans G et al. High levels of circulating testosterone are not associated with increased prostate cancer risk: a pooled prospective study. Int J Cancer 2004; 108: 418–424.

Huggins C, Stevens RE, Hodges CV . Studies on prostatic cancer: II. The effect of castration on advanced carcinoma of the prostate gland. Arch Surg 1941; 43: 209–212.

Nishiyama T, Ikarashi T, Hashimoto Y, Suzuki K, Takahashi K . Association between the dihydrotestosterone level in the prostate and prostate cancer aggressiveness using the Gleason score. J Urol 2006; 176: 1387–1391.

Platz EA, Leitzmann MF, Rifai N, Kantoff PW, Chen YC, Stampfer MJ et al. Sex steroid hormones and the androgen receptor gene CAG repeat and subsequent risk of prostate cancer in the prostate-specific antigen era. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005; 14: 1262–1269.

Zhang PL, Rosen S, Veeramachaneni R, Kao J, DeWolf WC, Bubley G . Association between prostate cancer and serum testosterone levels. Prostate 2002; 53: 179–182.

Hoffman MA, DeWolf WC, Morgentaler A . Is low serum free testosterone a marker for high grade prostate cancer? J Urol 2000; 163: 824–827.

Schatzl G, Madersbacher S, Thurridl T, Waldmüller J, Kramer G, Haitel A et al. High-grade prostate cancer is associated with low serum testosterone levels. Prostate 2001; 47: 52–58.

Yano M, Imamoto T, Suzuki H, Fukasawa S, Kojima S, Komiya A et al. The clinical potential of pretreatment serum testosterone level to improve the efficiency of prostate cancer screening. Eur Urol 2007; 51: 293–295.

Ribeiro M, Ruff P, Falkson G . Low serum testosterone and a younger age predict for a poor outcome in metastatic prostate cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 1997; 20: 605–608.

Imamoto T, Suzuki H, Fukasawa S, Shimbo M, Inahara M, Komiya A et al. Pretreatment serum testosterone level as a predictive factor of pathological stage in localized prostate cancer patients treated with radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 2005; 47: 308–312.

Massengill JC, Sun L, Moul JW, Wu H, McLeod DG, Amling C et al. Pretreatment total testosterone level predicts pathological stage in patients with localized prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2003; 169: 1670–1675.

Isom-Batz G, Bianco Jr FJ, Kattan MW, Mulhall JP, Lilja H, Eastham JA . Testosterone as a predictor of pathological stage in clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol 2005; 173: 1935–1937.

Imamoto T, Suzuki H, Akakura K, Komiya A, Nakamachi H, Ichikawa T et al. Pretreatment serum level of testosterone as a prognostic factor in Japanese men with hormonally treated stage D2 prostate cancer. Endocr J 2001; 48: 573–578.

Chodak GW, Vogelzang NJ, Caplan RJ, Soloway MS, Smith JA . Independent prognostic factors in patients with metastatic (stage D2) prostate cancer. JAMA 1991; 265: 618–621.

Teloken C, Da Ros CT, Caraver F, Weber FA, Cavalheiro AP, Graziottin TM . Low serum testosterone levels are associated with positive surgical margins in radical retropubic prostatectomy: hypogonadism represents bad prognosis in prostate cancer. J Urol 2005; 174: 2178–2180.

Partin AW, Pound CR, Clemens JQ, Epstein JI, Walsh PC . Serum PSA after anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. The Johns Hopkins experience after 10 years. Urol Clin North Am 1993; 20: 713–725.

Han M, Partin AW, Pound CR, Epstein JI, Walsh PC . Long-term biochemical disease-free and cancer specific survival following anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. The 15-year Johns Hopkins experience. Urol Clin North Am 2001; 28: 555–565.

Iversen P, Rasmussen F, Christensen IJ . Serum testosterone as a prognostic factor in patients with advanced prostatic carcinoma. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 1994; 157: 41.

Miller LR, Partin AW, Chan DW, Bruzek DJ, Dobs AS, Epstein JI et al. Influence of radical prostatectomy on serum hormone levels. J Urol 1998; 160: 449–453.

Prehn RT . On the prevention and therapy of prostate cancer by androgen administration. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 4161.

Lukkarinen O, Hammond GL, Kontturi M, Vihko R . Peripheral and prostatic vein steroid concentrations in benign prostatic hypertrophy patients before and after removal of the adenoma. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1980; 14: 225–227.

Madersbacher S, Schatzl G, Bieglmayer C, Reiter WJ, Gassner C, Berger P et al. Impact of radical prostatectomy and TURP on the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal hormone axis. Urology 2002; 60: 869–874.

Phadke MA, Vanage GR, Sheth AR . Circulating levels of inhibin, prolactin, TSH, LH, and FSH in benign prostatic hypertrophy before and after tumor resection. Prostate 1987; 10: 115–122.

Lokeshwar BL, Hurkadli KS, Sheth AR, Block NL . Human prostatic inhibin suppresses tumor growth and inhibits clonogenic cell survival of a model prostatic adenocarcinoma, the Dunning R3327G rat tumor. Cancer Res 1993; 53: 4855–4859.

Sheth AR, Garde SV, Mehta MK, Shah MG . Hormonal modulation of biosynthesis of prostatic specific antigen, prostate specific acid phosphatase and prostatic inhibin peptide. Indian J Exp Biol 1992; 30: 157–161.

Ghosh PK, Ghosh D, Ghosh P, Chaudhuri A . Effects of prostatectomy on testicular androgenesis and serum levels of gonadotropins in mature albino rats. Prostate 1995; 26: 19–22.

Risbridger GP, Shibata A, Ferguson KL, Stamey TA, McNeal JE, Peehl DM . Elevated expression of inhibin a in prostate cancer. J Urol 2004; 171: 192–196.

Yamamoto S, Yonese J, Kawakami S, Ohkubo Y, Tatokoro M, Komai Y et al. Preoperative serum testosterone level as an independent predictor of treatment failure following radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 2007; 52: 696–701.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (Contract grant numbers: 14207061, 17791066, 19591834 and 19791101), the Japanese Foundation for Prostate Research (2004), the Japanese Urological Association (2006) and the Yamaguchi Endocrine Research Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Compared with preoperative levels, serum testosterone and human luteinizing hormone levels were significantly elevated in parallel after radical prostatectomy, supporting the possibility that prostate cancer may inhibit serum testosterone levels by negative feedback of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Imamoto, T., Suzuki, H., Yano, M. et al. Does presence of prostate cancer affect serum testosterone levels in clinically localized prostate cancer patients?. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 12, 78–82 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2008.35

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2008.35