Key Points

-

CKD is an inherently systemic disease

-

Energy balance, innate immunity and neuroendocrine control of organ function are highly integrated biological processes; such integration is disrupted by loss of kidney function, which generates a high risk clinical phenotype

-

The clinical profile of chronic kidney disease (CKD) includes inflammation, malnutrition, altered activity of the autonomic and central nervous systems, and cardiopulmonary, vascular and bone disease

-

The gut and the lung are emerging as critical mediators of the interaction between the kidney and the environment, and are involved in cardiovascular disease and other systemic complications of CKD

-

Alterations in macrovascular and microvascular function induced by sleep apnoea, inflammation and oxidative stress increase the risk of brain disease in CKD

-

The application of omics sciences will enable in-depth studies of the pathophysiology and treatment of CKD

Abstract

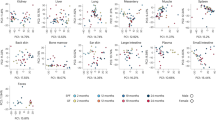

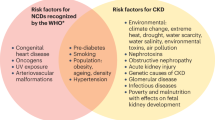

The accurate definition and staging of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is one of the major achievements of modern nephrology. Intensive research is now being undertaken to unravel the risk factors and pathophysiologic underpinnings of this disease. In particular, the relationships between the kidney and other organs have been comprehensively investigated in experimental and clinical studies in the last two decades. Owing to technological and analytical limitations, these links have been studied with a reductionist approach focusing on two organs at a time, such as the heart and the kidney or the bone and the kidney. Here, we discuss studies that highlight the complex and systemic nature of CKD. Energy balance, innate immunity and neuroendocrine signalling are highly integrated biological phenomena. The diseased kidney disrupts such integration and generates a high-risk phenotype with a clinical profile encompassing inflammation, protein–energy wasting, altered function of the autonomic and central nervous systems and cardiopulmonary, vascular and bone diseases. A systems biology approach to CKD using omics techniques will hopefully enable in-depth study of the pathophysiology of this systemic disease, and has the potential to unravel critical pathways that can be targeted for CKD prevention and therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The definition, classification and evaluation of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major achievement of modern clinical nephrology1. The widely accepted description of the disease and the staging system based on measurements of kidney function that can be reliably applied on a vast scale at reasonable cost, has been a formidable stimulus for clinical research2. This standardized way of looking at renal diseases has provided a common vocabulary and a shared approach to these diseases in clinical practice2,3. The natural history of the complications of CKD is, however, still being established in detail, and the prevalence and severity of the main metabolic and endocrine alterations associated with precise stages of CKD are currently being investigated4.

CKD has repercussions for other organs. For example, reduced renal function leads to hypertension, which when combined with other conditions can cause left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction, and eventually heart failure5. The term crosstalk has become fashionable to describe the relationships between the kidney and other organs. On close scrutiny, however, crosstalk is loosely used in clinical and biological contexts that might not be linked to one another. For example, in cross-sectional studies, the presence of renal biomarkers or histopathological changes in the kidney6 has been associated with the presence of endocrine factors or markers of distant organ dysfunction or damage (such as troponin7, B natriuretic peptides8 or other cardiac biomarkers9). In most clinical studies, crosstalk is used to highlight bivariate associations such as bone–kidney crosstalk10, rather than to describe complex multiorgan relationships. The lax use of this term has facilitated the emergence of new syndromic constructs such as cardiorenal syndrome and CKD–mineral and bone disorder (CKD–MBD), which has now gained the status of a syndrome11. In addition, the studies that described kidney–heart or kidney–bone relationships have questionable methodological underpinnings and largely fail to meet formal criteria for the definition of syndromes12,13.

The human body is a single biological entity. A reductionist approach can be valuable for the initial evaluation of phenomena that seem to be linked14, but reductionist constructs that evolve into criteria to identify new syndromes are problematic. Focusing on the relationship between the kidney and one or, at most, two distant organs15 does not take the unity of organisms into account and eclipses the systemic nature of chronic diseases16. The systemic complications of renal diseases were recognized at the beginning of the nineteenth century17 and the detrimental systemic consequences of renal function loss were described in thorough detail 45 years ago18.

In this Review, we describe the profound effect of renal function loss on several systems: energy metabolism, inflammation, neuroendocrine signalling, bone homeostasis, and the gastrointestinal, pulmonary and nervous systems. We provide examples of high-level integration of organ function that include the kidney and discuss how such integration is disrupted in CKD.

CKD disrupts the energy–immunity link

The regulation of energy balance is a fundamental homeostatic function of the human body that is orchestrated by diverse neuroendocrine pathways19. This function evolved, in part, to provide adequate energy levels to sustain short-lived inflammatory episodes, such as responses to infections or immune surveillance at the tissue level. Hence, immunity and metabolism are functionally coupled. The link between energy regulation and the immune system is also evident in daily life processes, such as the postprandial cytokine response to meal consumption20 or the effects of caloric and fat restriction on total leukocyte count21, and such coupling has an approximate circadian periodicity (Box 1; Fig. 1). Metabolic alterations (such as diabetes and bone mineral disorders (hyperparathyroidism) and immune dysfunction (autoimmune diseases such as lupus) profoundly affect the kidney and can even cause renal function loss. Vice versa, renal dysfunction can affect metabolic and immune balances. Examples of the influence of the kidney on metabolism include the increase in frequency of insulin resistance that is associated with deterioration of renal function, and the high levels of innate immunity biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6, that are present in patients with advanced stages of CKD.

Metabolic and endocrine responses can be promoted or inhibited in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). During the circadian cycle in these patients sympathetic activity is markedly increased, whereas the hypothalamic–pituitary axis is dysfunctional. Cortisol and glucagon levels are elevated mainly as a consequence of reduced renal clearance of these hormones and circadian changes in cortisol levels are abolished in this disease. Insulin levels are also high and insulin resistance is a hallmark of CKD. Similarly levels of growth hormone are substantially raised and this change is accompanied by marked resistance to its metabolic effects. Melatonin levels are depressed, particularly during the night, prolactin levels are elevated and the 24 h rhythmicity of these hormones is disrupted in advanced CKD. Gluconeogenesis is enhanced, whereas glycogenolysis shows an opposite response and these alterations in glucose metabolism are accompanied by reduced β-fatty acid oxidation and increased lipogenesis and lipolysis. Figure adapted with permission from John Wiley and Sons © Straub, R. H. et al., J. Intern. Med. 267, 543–560, (2010).

Energy storage and immunity

Energy-rich fuels are required to mount and sustain short-term inflammatory responses to environmental threats19. Glucose, glutamine and other glucogenic amino acids, free fatty acids and ketones are indispensable for the adequate functioning of the immune system. Cytokines such as IL-7 and IL-4, and hormones such as insulin and leptin, stimulate the uptake of glucose in immune cells via upregulation of glucose transporters22,23. When the immune system is activated, muscle proteins are degraded to supply amino acids for gluconeogenesis, a process that is fundamental to guarantee adequate provision of glucose to the brain.

Several neuroendocrine and inflammatory pathways control energy balance. The parasympathetic nervous system and pathways triggered by insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1 (Ref. 15), androgens, estrogens24 and osteocalcin25, facilitate the storage of energy-rich substrates. The parasympathetic system amplifies insulin sensitivity and secretion and promotes glycogen storage in the liver26. By contrast, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, the sympathetic system, thyroid hormones (such as cortisol27), glucagon28 and growth hormone trigger energy mobilization, that is lipolysis, glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis19.

In addition to promoting energy storage, the parasympathetic system has an important anti-inflammatory effect29, which is central to survival as uncontrolled inflammation can be life-threatening. The neuronal acetylcholine receptor subunit α-7, which is expressed in the nervous and immune systems, is a key regulator of the inflammatory response29 and triggers the cholinergic anti-inflammatory reflex (Ref. 30).

The sympathetic system, which is coupled to metabolism by insulin, a well-recognized sympathoexcitatory stimulus31, also contributes to the immune response. In stressful conditions, activation of the sympathetic system, which promotes glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis and lipolysis via its peripheral nervous fibres and the adrenal medulla32, helps to fuel the immune system in order to mount an adequate inflammatory response15. Conversely, sympathetic denervation ablated the early inflammatory response in an experimental model of arthritis33.

Stimulation of the two arms of the autonomic system produces opposite effects on energy balance and activation of the immune system. The parasympathetic system is geared towards facilitating energy storage and restraining inflammation, whereas the sympathetic system facilitates energy mobilization and consumption and potentiates inflammation. Overall, the autonomic system, the immune system and metabolism are tightly linked to ensure perfect integration of these systems in homeostasis and life-threatening situations15.

Inflammation

The level of inflammatory mediators increases progressively as renal function declines34. Among 3,939 patients enrolled in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort study, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), albuminuria and the levels of cystatin C strongly correlated with the levels of IL-6, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), inverse acute phase reactants such as albumin, and fibrinogen, which mediates the effect of inflammation on the coagulation system35. The levels of serum fetuin-A, which is another major inverse acute phase reactant, the most potent circulating inhibitor of calcium phosphorus precipitation and an inhibitor of insulin sensitivity, decline as renal function deteriorates36. Inflammation is multifactorial in CKD and this disease is considered to be a prototypical example of inflammatory disease and premature ageing37 (Fig. 2). Proinflammatory factors in CKD include reduced cytokine clearance38; infections39 such as periodontal disease40; oxidative stress41; senescence-associated muscle cell phenotype42; hypogonadism43; accumulation of advanced glycation end-products44 and toxins absorbed in the gut45; sodium overload46; metabolic acidosis47; bone mineral disorders48; accumulation of calciprotein particles49; autonomic imbalance50; insulin resistance51; intradialytic hypoxaemia52; and genetic53 and epigenetic54 factors. Thyroid hormone, which regulates thermogenesis by potentiating adrenergic stimulation at the receptor level55, is downregulated in advanced CKD. This alteration is considered to be a protective mechanism that limits the energy expenditure of the inflammatory response56,57.

High levels of cytokines, metabolic acidosis, volume and sodium expansion, the presence of uraemic toxins and sleep apnoea (owing to sympathetic overactivity) contribute to insulin resistance in chronic kidney disease (CKD). Proinflammatory mechanisms activated by renal dysfunction might accelerate progression of CKD. Insulin resistance triggers inflammation and vice versa. Genetic and epigenetic factors act as modifiers of endogenous and environmental factors responsible for inflammation in CKD.

The inflammation–autonomic system interface. High sympathetic activity can trigger and/or modulate inflammation in CKD through multiple pathways such as interferon-γ, IL-6 and IL-10 (Ref. 58). Dysfunction of the intestinal barrier in CKD can promote the absorption of inflammatory toxins from the gut59,60 and can lead to the release of the sympathetic neurotransmitter, neuropeptide Y, a fundamental orchestrator of the link between the gut and the autonomic and central nervous systems61. The contribution of the gut to the systemic effects of CKD is discussed further below. High levels of proinflammatory cytokines including TNF62, IL-6 (Ref. 63), leptin64, and fairly low levels of adiponectin65, regulate insulin sensitivity and energy balance in patients with CKD.

The autonomic system acts as a powerful orchestrator of inflammation and a modulator of energy balance66. CKD and high CRP levels are independently associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular events, whereas CKD and high levels of the sympathetic neurotransmitter noradrenaline have a synergistic effect on the risk of stroke67. Chronic inflammation in CKD maintains a catabolic state that leads to sarcopenia and protein-energy wasting12,68,69. Common complications of CKD, such as anorexia, cachexia, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, anaemia and high sympathetic activity, can be considered to be consequences of disturbed energy regulation as a result of chronic inflammation19. A parasympathetic anti-inflammatory reflex is generated by cytokines in inflamed organs29,30, whereas sympathetic activation has a proinflammatory effect33. Persistent sympathetic activation can trigger cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis through activation of the immune system58. Accordingly, in patients with stage 3–5 CKD, concentric left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with inflammation70,71 and with high levels of noradrenaline72 and neuropeptide Y73. High levels of these biomarkers underlie high cardiovascular risk in CKD74,75.

Hypoxia. The inflammatory milieu in CKD and other chronic diseases is characterized by tissue hypoxia76. Inflammatory stimuli impair nitric oxide synthesis and lead to endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, which is a key step in capillary rarefaction and ensuing tissue hypoxia in the kidney77. The rarefaction of peritubular capillaries is a hallmark of tubulointerstitial alterations, including macrophage infiltration and fibrosis, that accompany the decline in GFR in CKD78. Tubulointerstitial hypoxia and the ensuing activation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors occurs in the advanced stages of the disease79. An imbalance between hypoxia-inducible pro-angiogenic compounds (such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and angiopoietins) and angiogenesis inhibitors (such as angiostatin and thrombospondin-1) underlies capillary rarefaction in CKD79. The importance of maintaining a tight balance between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors is highlighted by the observation that use of angiogenic factors, such as VEGF, to increase oxygenation of the tubule interstitium results in inflammation and in an increase in vascular permeability and proteinuria, whereas VEGF blockade causes hypertension80 and thrombotic microangiopathy81.

Oxidative stress and accumulation of advanced glycation end-products can lead to inflammation in CKD and might contribute to adverse renal and cardiovascular outcomes44. High levels of reactive oxygen species owing to inflammation have a primary role in the development and/or aggravation of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidities in CKD82 and in kidney failure41. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) (Box 2) protects the kidney from renal ischaemia and acute kidney injury83, but HIF function might be inhibited by oxidative stress and uraemic toxins84. Indoxyl sulfate accumulates in CKD and dose-dependently suppresses the transcriptional activity of HIF85 and the expression of Klotho86, a crucial anti-inflammatory and anti-ageing factor37. Ongoing studies are testing whether activation of HIF might have a beneficial effect on maintenance of renal function in models of CKD, such as the remnant kidney model87. HIF stabilizers such as prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors improve anaemia in CKD88. Inflammation and oxidative stress could be seen as a trade-off of the hormonal response aimed at countering phosphate accumulation in CKD89. The link between bone mineral disorders and the systemic effects of CKD is discussed below.

Insulin resistance. Insulin resistance occurs in the early stages of CKD90,91 and is present in almost every patient with end-stage renal disease (ESRD)92. The mobilization of energy-rich fuels through activation of neuroendocrine pathways results in high levels of free fatty acids, which lead to insulin resistance in the liver, muscle cells and adipocytes in chronic inflammatory conditions93. Insulin resistance is also common in other chronic conditions, such as cancer94 and rheumatoid arthritis95, and is promoted by altered levels of cytokines, particularly TNF96, IL-6 (Ref. 97), leptin, adiponectin98 and resistin99, which are typically seen in chronic inflammation.

In contrast to other cell types, immune cells do not develop insulin resistance. Fairly brief energy-demanding inflammatory responses are protective, but in persistent inflammatory states a sustained energy flow to the immune system disrupts the balanced distribution of fuels to various stores and organs19 and can result in organ damage, protein depletion, negative caloric balance and metabolic adaptations (such as insulin resistance), disease and disability100,101.

Sodium, hypertension and inflammation. The risks of CKD progression102 and cardiovascular events103 in patients with stage 3–5 CKD are linearly associated with high levels of sodium, the most abundant electrolyte in extracellular fluids. Sodium is involved in inflammation in hypertension and because sodium levels are in part regulated by the kidney, sodium links the kidney104 to other systems including the integumentary system105. For example, a high-salt diet causes interstitial hypertonic accumulation of sodium in the skin and VEGF-C secretion by macrophages. Inhibition of VEGF-C or mononuclear phagocyte system cell depletion increased interstitial hypertonic volume retention, reduced expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and caused hypertension in response to high-salt intake106.

Metabolism, the bone, the heart and CKD

Bone mass increases dramatically during growth and preserving skeletal mass during adult life is an absolute functional priority for vertebrates. Phosphate is an anion that is mainly stored in the bone. Given the key role of phosphate in energy metabolism and the structural importance of inorganic phosphate salts in bone, a complex biological system has evolved to link bone to other organs and to adjust phosphate balance to changing physiological requirements and to the availability of nutrients and energy107. Phosphate is a fundamental compound for the myocardium and both low108 and high phosphate levels109 have detrimental effects on the heart. Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23), the main bone-derived hormone that regulates phosphate excretion by the kidney, is involved in myocardial cell growth and in left ventricular hypertrophy110.

CKD uncouples mineral and glucose metabolism

Osteocalcin links bone, the sympathetic system and energy metabolism. Osteoblasts secrete osteocalcin, one of the most abundant non-collagen bone proteins. Osteocalcin regulates bone mineralization and modulates osteoblast and osteoclast function. γ-Carboxylation is essential for osteocalcin biological function and depends on vitamin K levels. Osteocalcin is also a key mediator of the coupling between bone and energy metabolism as it regulates insulin synthesis at the transcriptional level and potently stimulates insulin secretion111. Osteocalcin-knockout mice have decreased glucose tolerance, insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity112. In humans, the concentration of circulating uncarboxylated forms of osteocalcin depends on vitamin K status and bone turnover, and vitamin K levels inversely correlate with GFR113. Of note, in osteoblasts, sympathetic activation enhances the expression of Esp (also known as Ptprv), which encodes osteotesticular protein tyrosine phosphatase, an osteocalcin inhibitor and an insulin secretagogue111. These findings highlight the tight relationship between glucose homeostasis and the bone114.

In epidemiological and clinical studies, circulating levels of osteocalcin inversely correlated with those of insulin resistance markers (defined according to the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance criteria) in most, but not all, surveys111. Changes in circulating levels of osteocalcin triggered by treatment with risedronate in 87 patients with osteoporosis were not associated with changes in glucose or insulin levels115. In three large trials that tested the effects of antiresorptive therapy with alendronate, zeledronic acid or denusomab in postmenopausal women, the treatment, which also reduces osteocalcin levels, did not alter insulin and glucose levels116. Thus, whether osteocalcin has a meaningful effect on glucose metabolism in humans remains unresolved. Differences in osteocalcin genetics, levels, and metabolism between humans and mice could all account for this discrepancy117.

In patients with moderate to severe CKD, ostecalcin carboxylation is disrupted owing to vitamin K deficiency118 (Fig. 3). This metabolic alteration can be corrected by vitamin K1 administration119. High levels of uncarboxylated osteocalcin are associated with low levels of plasma glucose, haemoglobin A1C, and glycated albuminin in patients with CKD120, suggesting that the lack of carboxylated forms of osteocalcin might contribute to the alteration of glucose metabolism in these patients.

Altered levels of several molecules such as bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone (PTH), fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23), insulin, uraemic toxins and cardiac natriuretic peptides, as well as dysfunctional processes such as altered energy balance, adipocyte function, blood pressure and volume control are key risk factors for chronic kidney disease (CKD), bone disease and cardiovascular disease.

FGF-23 bridges multiple organs and systems. In addition to modulating osteocalcin levels121, the sympathetic nervous system regulates the expression of FGF-23 in the bone122. FGF-23 regulates energy metabolism (Fig. 3), induces left ventricular hypertrophy123,124, and mediates the relationship between the bone and the vascular system. Moreover, FGF-23 is functionally linked to the renin–angiotensin system (RAS); high levels of FGF-23 inhibit the expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2125 and induce low levels of calcitriol, which can promote renin production.

High circulating levels of FGF-23 are associated with insulin resistance in adolescents with obesity126 and correlate with various measures of adiposity including BMI, waist circumference and fat mass in elderly individuals127. High levels of this hormone and/or low levels of its co-receptor Klotho are likely causative factors of cardiovascular disease128,129 and of progressive loss of renal function in CKD130,131,132.

FGF-23 (Ref. 89) and Klotho133 are highly responsive to inflammation19. In mouse models of chronic inflammation, the c-terminal portion of FGF-23 is overexpressed, leading to elevated circulating levels of the peptide134. Accordingly, the levels of inflammation markers and of C-terminal FGF-23 in the circulation correlate directly in patients with CKD89. In wild-type mice, acute inflammation induced by a single injection of heat-killed Brucella abortus or IL-1β led to increased FGF-23 cleavage, but the levels of full-length FGF-23, the biologically active form of the hormone, were almost unaltered, presumably owing to FGF-23 overexpression134. By contrast, in patients with CKD, the levels of full-length FGF-23 were 50% lower during acute inflammation secondary to sepsis than after the resolution of this condition, whereas the levels of C-terminal FGF-23 remained unaltered during and after sepsis, potentially owing to suppression of endogenous inhibitors of proteolytic enzymes such as furin pro-pro convertase, which cleave full-length FGF-23 during acute sepsis135. High levels of FGF-23 irreversibly compromise neutrophil function and recruitment to inflamed tissues136.

FGF-23 is also a powerful inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis137. The downregulation of FGF-23 expression in acute inflammatory processes might be an ancestral, life-saving response to acute sepsis. This hypothesis is supported by the simultaneous declines in the levels of FGF-23 and asymmetric dimethyl arginine (ADMA), another potent inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, that occur during sepsis138. These declines result in increased synthesis of nitric oxide, which has a strong bactericidal action. The observation that inhibition of nitric oxide synthase increases mortality in patients with sepsis further supports the hypothesis that unabated nitric oxide production is fundamental for survival in acute sepsis139.

Inflammation is profoundly integrated with systems that control energy balance and is a strong modifier of bone resistance to parathyroid hormone140, which is a hallmark of ESRD. The inflammatory adipokine leptin and the anti-inflammatory adipokine adiponectin have a major influence on bone mass in experimental models141 and leptin is associated with low bone-turnover in kidney failure142.

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs). BMPs are members of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily that regulate glucose homeostasis and energy metabolism in the adipose tissue and in the setting of inflammation143. BMPs are required for the formation of brown adipocytes and for the browning of white adipose tissue and the related beneficial effects on energy expenditure and adiposity143. Polymorphisms in BMP2 seem to have a critical role in inflammation in patients with CKD144. BMP2 stimulates MS X2, which encodes a protein with a role in regulation of bone mass, and enhances phosphate uptake in vascular smooth muscle cells so promotes calcification145. BMP2 levels are elevated and might contribute to arterial stiffness in patients with CKD146 (Fig. 3). Some BMPs (such as BMP1 or BMP3) induce kidney fibrosis by binding to TGF-β superfamily type II receptors, whereas others (such as BMP7) prevent fibrosis147,148. The effects of BMP on these receptors are modulated by several pathways, including the activin pathway148. The novel activin antagonist RAP-011 is currently being explored as a new therapeutic strategy to counter vascular calcification and kidney fibrosis in CKD, as well as to modulate glucose homeostasis and energy metabolism of adipose tissue148.

Cardiac natriuretic peptides. Cardiac natriuretic peptides have a fundamental role in the cardiovascular and renal response to volume expansion, they participate in the regulation of energy metabolism149,150, they have anti-inflammatory151 and sympatholytic effects152, and they regulate bone homeostasis. For example, c-type natriuretic peptide regulates osteoblast autocrin and paracrine signalling, osteoclast bone resoprtion and chondrocyte proliferation in vitro153,154,155 and transgenic mice that overexpress brain natriuretic peptide (BNP, also known as natriuretic peptide B) are characterized by skeletal overgrowth156. Patients with stage 5D CKD have very elevated levels of BNP157, which are strongly associated with left ventricular mass index and predict mortality in a dose-dependent manner157. No evidence has been yet provided that the plasma levels of this peptide have an effect on bone mineral disorder in CKD. The effects of altered levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D or parathyroid hormone on cardiovascular158 and bone disease159, and on impairment of energy metabolism in CKD160 are extensively reviewed elsewhere.

Overall, these findings highlight the systemic nature of CKD as this condition affects bone and the vascular system through inflammation and hormones that regulate energy balance. In turn, these systems contribute to CKD comorbidities and disease progression.

CKD alters the gut-kidney link

In CKD the gut and the kidney influence each other in a dual way (Fig. 4). Several uraemic toxins that enter the body via the intestine, depend on the kidney for their excretion so accumulate with loss of renal function161. Conversely, the uraemic status affects the intestinal microbiome and the integrity of the intestinal wall, which in turn influences toxin generation and inflammatory status, increasing toxicity and hence, systemic complications and mortality in CKD162,163. The potential importance of the gut–kidney link is highlighted by the association between constipation and excess risk of CKD observed in a large cohort of US veterans164. Dimethylarginines (ADMA and symmetric dimethylarginine)165 and advanced glycation end-products166 originate at least in part from food components in the intestine and have been linked to inflammation44,167, CKD progression44,168 and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality169,170,171.

Aswell as causing the retention of uraemic toxins (including toxins generated in the intestinal system), chronic kidney disease (CKD) alters the integrity of the intestinal barrier, which leads to translocation of intestinal microbiota into the blood, systemic inflammation, increased absorption of uraemic toxins from the intestine and cardiovascular disease. Uraemic toxins are strong proinflammatory stimuli. Cardiovascular disease also contributes to alter the intestinal barrier via venous intestinal congestion secondary to heart failure.

Perhaps the most important role of the intestine in the generation of toxic compounds that affect the gut–kidney axis (Fig. 4) can be attributed to the breakdown of digestive products such as amino acids by the microbiota into precursors of uraemic retention products, especially indoles and phenyl derivatives172. Bacteria that form indole and cresol are predominant in the intestinal microbiome of patients with ESRD162, which explains the progressive increase in p-cresol levels that occurs in the late stages of CKD173,174. Thus, the intestine produces uraemic toxins and this generation increases as kidney disease progresses. High levels of p-cresol and indoxyl sulfate have well-recognized effects on several organs, such as osteoblast dysfunction and low turnover in the bone175,176 and proinflammatory effects in the vascular system as a result of increased leucocyte adhesion and rolling177. Furthermore, both molecules have been linked to cardiovascular diseases and death in ESRD178.

CKD can damage the intestinal wall barrier179, increasing endotoxin leakage and translocation of intestinal bacteria, which enhance inflammation and cause cardiovascular and renal damage180. Heart failure also increases intestinal leakiness independently of CKD181. Among patients with CKD, intestinal p-cresol uptake is higher in those with cardiovascular disease, independent of kidney function182. Moreover, the composition of the intestinal microbiome influences the severity of experimental myocardial infarction183. Cardiovascular disease might, therefore, impair the function of the intestinal microbiome irrespective of CKD, suggesting that microbial products might have toxic effects in clinical conditions other than CKD.

The intestinal microbiome also generates trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), a metabolite of dietary phosphatidylcholine and choline184. Plasma levels of TMAO increase exponentially with decreasing kidney function185 and are associated with mortality and cardiovascular events in CKD186. TMAO could therefore be an intestinally generated cardiotoxic agent that is present at high concentrations in patients with kidney disease. The effects of TMAO might even go beyond the cardiovascular system and extend to bone growth in children187, the brain188, the endocrine system189 and thrombosis190.

A 2014 systematic review identified numerous studies that reported deleterious effects of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate, such as cardiovascular disease, inflammation and progression of kidney failure178. These toxins also mediate the crosstalk between leukocytes and the vascular wall, a process that is considered to be essential for the initiation of atherogenesis177. In a model of acute kidney injury, indoxyl sulfate rapidly accumulated in the nervous system, suggesting that this toxin might be involved in the neural dysregulation that is triggered by kidney dysfunction191. Furthermore, accumulating evidence indicates that the gut microbiome might exert important effects on the nervous system through multiple pathways including bacterial metabolites, inflammatory cytokines, and neurotransmitters192. Indole acetic acid, which has proinflammatory and pro-coagulatory properties193,194, and phenyl acetic acid, an inhibitor of inducible nitric oxide synthase195, are also generated in the intestine and have toxic potential.

Symbiotic therapy196 (oral intake of a combination of high–molecular weight inulin, fructo-oligosaccharides, galacto-oligosaccharides and a probiotic component including nine different strains across the Lactobacillus, Bifidobacteria and Streptococcus genera) or a reduction in protein intake combined with ketoanalogue administration197 (a dietary intervention that can have beneficial effects on renal disease progression and systemic complications of uraemia179) can be used to mitigate the intestinal generation and uptake of toxic compounds. However, the use of intestinal sorbents to adsorb uraemic toxins did not improve hard outcomes such as progression of kidney failure in patients with CKD stage 3 or 4180,181. These findings need to be confirmed because toxin concentration was not assessed in one study180 and the other could not demonstrate the expected decrease in indoxyl sulfate levels with adsorbent administration181.

Overall, the generation and retention of toxic compounds of intestinal origin and the structural changes associated with uraemic and cardiovascular diseases can jeopardize renal, intestinal and cardiovascular integrity by similar pathophysiologic mechanisms (Fig. 4), resulting in a vicious circle that can lead to complications, hospitalization, and death. As kidney disease progresses, multiorgan damage worsens exponentially and could at least partly explain the exponential increase in mortality that is associated with progression of kidney failure.

Kidney and lung dysfunction

The lung is constantly exposed to a myriad of changing environmental stimuli and to toxins such as air pollutants, which are risk factors for both lung and kidney disease. For example, ultrafine particles can not only cause lung disease, but also cardiovascular198 and renal diseases199.

Neuroendocrine cells — an evolutionarily conserved, sparse population of innervated epithelial cells — are essential mediators of the pulmonary response to environmental stimuli181. They induce a neural reflex in the lung that regulates cytokine release and modulates inflammation and immune cells function200. The contribution of innervation density and neural reflexes to pulmonary inflammatory and immune responses is highlighted by the aggressive alloimmune reaction that follows lung transplantation201. In addition, neuroendocrine lung cells are key players in common lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease202. Of note, the number of neuroendocrine (calcitonin+) cells was considerably increased in the lungs of subtotally nephrectomized rats, compared with control animals203. Neuroendocrine cell overpopulation in the lung in patients with advanced CKD might be a compensatory phenomenon to mitigate local inflammation.

The effects of CKD on the risk of obstructive and restrictive lung diseases have received scarce attention to date. In a representative sample of US adults, GFR <60 mm/min/1.73 m2 was associated with an increased risk of obstructive lung disease, whereas albuminuria was associated with obstructive and restrictive lung diseases; these relationships were independent of other risk factors204. The link between albuminuria and pulmonary disease is most likely multifactorial. Hypoxia might be a major driver of this association as it is a potent activator of the sympathetic system and high sympathetic activity is associated with proteinuria and reduced GFR in patients with CKD205. Proteinuria is more common in people who live at altitudes >2,400 m than in those who live at sea level206, potentially owing to constant hypoxia. Similarly, in patients with pulmonary disease, hypoxia might cause inflammation and oxidative stress207 and thus trigger albuminuria.

In the early stages of acute kidney injury, the lung undergoes inflammation independent of infection, and lung dysfunction is detectable within hours after kidney injury208. In patients with ESRD, chronic inflammation and elevated levels of several cytokines exist209, and levels of IL-6 and CRP are very powerful predictors of the risk of death210. Patients with ESRD maintained on dialysis have a high risk of emergency hospitalization for pulmonary oedema, and lung congestion in this population is incompletely accounted for by heart failure211. This increased risk might be in part due to chronic inflammation. Indeed, interstitial accumulation of water in the lung in patients with ESRD is associated with systemic inflammation as reflected by high serum levels of CRP212. Notably, pulmonary hypertension, another potential consequence of chronic lung inflammation213, is much more frequent in patients with stage 3–5 CKD214,215 and in patients undergoing dialysis216 than in the general population. As mentioned below, hypoxic episodes during sleep apnoea — a disease characterized by chronic inflammation217, persisting sympathetic overactivity218 and pulmonary hypertension219 — are increasingly common as renal function deteriorates220 and evolve to become almost universal in patients maintained on chronic dialysis221. Thus, ample evidence demonstrates that the lung and the kidney are linked through neuroendocrine-mediated inflammation and that this relationship is bidirectional.

Neuropathology in CKD

The kidney and the nervous system are linked by multiple inter-related pathways. For example, a close relationship exists between the sympathetic system, critical renal systems such as the RAS, and the brain222. The physiological and behavioural adaptations that have evolved to minimize changes in osmolality also exemplify the interactions between the kidney and the nervous system223. Renal excretion of sodium and water counterbalances alterations in the circulating volume, and blood tonicity is maintained in a narrow range by vasopressin (also known as antidiuretic hormone), which is secreted by the nervous system and acts on the kidney224. Sensors of blood osmolality (osmoreceptors) are not restricted to the brain; they are also present in the liver portal vein (peripheral osmoreceptors) where they detect the osmotic effect of foods and fluids entering the gastrointestinal system225. Systemic changes in osmolality are detected in critical areas of the central nervous system, including the supraoptic and preoptic nuclei, the subfornical organ, and the organum vasculosum lamina terminalis226. Neuronal activity in these areas of the nervous system modifies vasopressin secretion and hence free water clearance, and stimulates or inhibits thirst and sodium appetite226.

Another major function of the nervous system in mammals is control of the circadian clock227. The suprachiasmatic nucleus in the hypothalamus is the central system that synchronizes peripheral systems227. Central and peripheral synchronizers share a common molecular clock that consists of self–sustained transcriptional and translational feedback loops228. The circadian regulation of a variety of processes such as sodium excretion, blood pressure control, and circadian neuro-endocrine rhythmicity are notoriously altered in CKD229. The permeability of the blood–brain barrier to small solutes such as sucrose and inulin is enhanced in the advanced stages of CKD and is associated with increased potassium transport and disturbed sodium transport230. The relationship between these dysfunctions and altered mental function in CKD remains elusive231.

Patients with CKD can have neurological complications such as cognitive disorders232, dementia233, cerebrovascular diseases234 and peripheral neuropathy. Conventional risk factors for cardiovascular disease (such as old age, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia and atrial fibrillation) might induce neurological disorders in CKD, mainly through microvascular disease. Risk factors associated with low eGFR, including albuminuria235, altered NF-κB–TNF and Klotho signalling236 and increased levels of β2-microglobulin237, are independently associated with structural and functional cerebral changes. In the systemic scenario of CKD, which is characterized by renal and cerebrovascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, excess RAS activation and oxidative stress234, the levels of a substantial number of neuromediators and endocrine factors (such as β-endorphin, methionine-enkephalin, adrenomedullin and neuropeptide Y) are temporally (circadian rhythms) and quantitatively altered229,238. These changes are thought to have a role in the high incidence of neurological complications in CKD, but this hypothesis remains to be tested.

Sleep apnoea is one of the most common complications in patients with advanced CKD (Fig. 5). Conversely, sleep apnoea can cause CKD, as clearly shown by large two community-based studies239,240. In the first study, which included 4,674 patients with and 23,370 individuals without sleep apnoea, this condition was associated with a 94% excess risk of CKD (HR 1.94; 95% CI, 1.52–2.46) and a 120% excess risk of ESRD (HR 2.2; 95% CI, 1.31–3.69; P < 0.01)239. In the second study, which included >3 million US veterans, patients with untreated sleep apnoea had a 127% (HR 2.27; 95% CI 2.19–2.36) excess risk of ESRD, whereas the same risk was 179% higher (HR 2.79, 95% CI 2.48–3.13) in patients receiving treatment for sleep apnoea than in patients without sleep apnoea240.

In chronic kidney disease (CKD), sleep apnoea is triggered by mechanisms initiated in the central nervous system and by fluid retention leading to pharyngeal narrowing and airway obstruction. Conversely, sleep apnoea can cause CKD via hypoxia and inflammation. Sleep apnoea has major detrimental effects on the cardiovascular system via the development of hypertension, high sympathetic activity, activation of the RAS and aldosterone, insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction and inflammation. RAS, renin–angiotensin system; SNS, sympathetic nervous system.

Sleep apnoea has a wide-range of systemic effects including inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, pulmonary hypertension, left ventricular dysfunction and hypertension, which are typically associated with CKD241. The circadian pattern of the blood pressure profile is often inverted in patients with kidney failure and nocturnal hypoxaemia242. Studies in animal models and clinical studies show that sleep apnoea causes neurodegeneration via hypoxia, hypertension, vascular dysfunction, inflammation, and oxidative stress243. Moreover, serum amyloid levels are more than doubled in patients with moderate to severe sleep apnoea compared with those with mild sleep apnoea or healthy controls244. Well before the appearance of any neuropsychological symptoms, patients with sleep apnoea have grey matter loss in the frontal and temporo-parieto-occipital cortices, the thalamus, the hippocampal region, some basal ganglia and cerebellar regions245. Brain alterations and grey matter loss are commonly seen in CKD, particularly in patients with ESRD246. These alterations are clinically relevant as they are associated with cognitive impairment and with a high risk of death in CKD247.

Overall, the kidney has an important influence on the complex neural network that regulates essential functions such as thirst and water balance, sodium appetite and excretion, and circadian rhythms. CKD alters sodium and water metabolism, cerebrovascular function and several neurohormonal signalling mechanisms, which eventually lead to and/or aggravate various neurological complications of CKD spanning from sleep apnoea to peripheral neuropathy and dementia.

Next steps: a systems biology approach

A whole body perspective

From a whole-body perspective, the multiple links between the kidney and other organs generate a complex set of physiological and pathological interactions that are difficult to understand through the study of bilateral interactions between two organs. For example, the links between the kidney and the lungs in sleep apnoea are insufficient to explain the multifaceted pathophysiology of this syndrome, which is characterized by systemic inflammation, nocturnal hypertension, cardiovascular dysfunction and brain dysfunction. Systems biology approaches can provide further insights into the systemic nature of diseases248. Unraveling multiple pathophysiologic associations between organs in CKD is now a concrete possibility (Table 1). However, integrating the large quantity of information that will be generated by the systems biology approach will require technical advances such as those seen in imaging and network analysis. These tools could be generated with research efforts such as those deployed by the United States Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies Initiative249.

A systems biology approach

In the current post-genomic era, systems biology has the potential to enable in-depth investigation of the nexus between molecular function at the cellular and subcellular levels and whole-body integration. Understanding of how the function of a myriad of proteins translates into the complex and integrated activity of cells, tissues and organs systems, and how altered molecular regulation of these activities by CKD might lead to organ dysfunction, is now possible.

A systems biology approach enables simultaneous analysis of the full set of molecular changes occurring at different levels and in different organs. The epigenome can provide insights into the effects of uraemia and the resulting inflammation on heritable modifications of DNA, histones and microRNAs that modulate gene expression without modifying the DNA sequence250. For example, kidney-injury-associated inflammation decreases Klotho expression in part through epigenetic modulation251. Analyses of the transcriptome enable the detection of detailed changes in gene expression in CKD to refine the molecular definition of CKD-associated inflammation and organ dysfunction252.

Our understanding of uraemic toxicity can also be furthered by a systems biology approach. At the proteomic level, differential levels of protein expression253 and post-translational protein modifications resulting from altered gene expression or uraemic toxicity can be precisely defined, setting the stage for novel therapeutic approaches. For example, post-translational modifications that change protein half-life or function, such as carbamylation, or high levels of methylglyoxal-derived advanced glycation end-products have been identified in patients with uraemia254.

Metabolomics and metagenomics

Changes in the levels of metabolites, such as asymmetric dimethyl arginine255 or long-chain acylcarnitine256, that contribute to complications in CKD and are involved in cardiovascular complications in patients undergoing dialysis169,256 can be reliably measured and are providing new insights into the pathogenesis of complications associated with uraemia255,256,257. Studies at the metagenomic level, that is on genetic material from bacterial communities such as the gut microbiota, provide insights into the effects of CKD on the microbiome and, conversely, on the effects of changes in the microbiome on the manifestations of CKD. Metagenomic studies in mice have shown that the metabolism of dietary l-carnitine (which is abundant in red meat) by certain taxa of the intestinal microbiota generates trimethylamine, which is processed by the liver into pro-atherogenic and prothrombotic trimethylamine-N-oxide190,258. Changes in the gut flora induced by diet and uraemia-associated trimethylamine-N-oxide accumulation259 modify the manifestations of CKD and might underlie the clinical variability and discrepancy seen in the results of different studies260.

Integration of omic sciences

The possibility that the complexity of renal diseases could be unraveled by studies based on new systems biology technologies is tantalizing because full understanding of pathophysiological processes requires the integration of several omics datasets (from biological fluids or tissues) into a dynamic model of the molecular changes in CKD through 'trans-omic' analyses261. In this regard, the process has started with the application of systems biology tools to simple sets of samples (which can be obtained from plasma, urine, faeces or circulating leukocytes). For example, one study performed metabolomics analyses in a group of 41 patients with stage 3–4 CKD255, whereas another analysed metabolic signatures in urine samples of a small series of 13 patients with stage 4–5 CKD257.

In the future, the complexity of the samples can be expected to increase. Indeed, understanding of the effects of CKD and uraemia on the epigenome, transcriptome, proteome and metabolome of individual organs such as the heart will require additional tissue analyses with techniques such as imaging, which enables visualization of the heart structure. These analyses will also have to be integrated with the genetic background of the individual, which can be studied by exome or whole genome sequencing. Progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis and the manifestations of CKD and the uraemic syndrome is likely to be a slow, decades-long process. The full development of new informatic and biostatistical tools to integrate the large amount of biological data generated by the various omics sciences, from genomics262 to metabolomics263, will be central for the advancement of knowledge on CKD.

Personalized renal care

To achieve the ambition of personalized care for patients with renal diseases, understanding of not only how renal diseases arise, but also how they affect all organs at the molecular and individual level would be useful. Developing such a comprehensive view of renal diseases and generating practical clinical applications of this knowledge might take at least 10–15 years264. Such an undertaking seems worthwhile if one considers the uraemic syndrome and CKD with a holistic perspective and recognizes that many systems are intertwined; unravelling all the links in the network will, therefore, likely lead to improvements in patient outcomes.

Treatments that target critical integrative pathways such as inflammation and the autonomic system might mitigate the systemic effects and progression of CKD. To date attempts to interfere with these systems have been disappointing265, but thorough proteomic and metabolomic analyses might lead to the discovery of novel critical biological targets for therapy and the development of innovative drugs with increased efficacy and reduced adverse effects.

Systems biology tools such as proteomics evolve rapidly and can be applied to the investigation of the biology of chronic diseases. Proteomics has proven to be an effective tool to identify drug targets in cancer, a chronic condition that involves extensive protein networks266, much like CKD267. In the specific context of CKD, rich databases that combine findings at various biological levels have already been created268. These databases, which will potentially be fuelled by future discoveries, will soon provide critical information for our understanding of the complexity of CKD and its systemic complications, thereby enabling the discovery of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets268.

Conclusions

Traditionally, medicine aims to isolate the most relevant single factor responsible for a disease: a bacterium or a virus in an infectious process, a gastroduodenal ulcer in anaemia due to blood loss, the tumour mass in cancer248. Such an approach has been and remains crucial but, in the context of multifactorial, complex diseases, failing to capture critical multiorgan information is inherently inadequate. Until recently, the analytical tools available for medical research were not adapted to addressing complex questions. In kidney diseases, we define syndromes such as the cardiorenal syndrome, cardiorenal anaemia, and CKD–MBD12,13, but CKD269 and uraemia270 are systemic diseases. With emerging omic sciences and personalized medicine, CKD syndromes built on uncertain grounds might soon be considered just as descriptive expressions of this multifaceted disease.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

17 May 2017

In the html and pdf versions of this article originally published online the permissions line for Figure 1 was not included. This error has now been corrected online and in print.

References

KDIGO. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 3, 19–62 (2013).

Eckardt, K.-U. et al. Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet 382, 158–169 (2013).

MacCluer, J. W. et al. Heritability of measures of kidney disease among Zuni Indians: the Zuni Kidney Project. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 56, 289–302 (2010).

Barrett Bowling, C. et al. Age-specific associations of reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate with concurrent chronic kidney disease complications. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 6, 2822–2828 (2011).

Zoccali, C., Bolignano, D. & Mallamaci, F. in Oxord Textbook of Clinical Nephrology 4th edn Ch. 107 (eds Turner, N. N. et al.) 837–852 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2015).

Maarouf, O. H. et al. Paracrine Wnt1 drives interstitial fibrosis without inflammation by tubulointerstitial cross-talk. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 781–790 (2015).

Abbas, N. A. et al. Cardiac troponins and renal function in nondialysis patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin. Chem. 51, 2059–2066 (2005).

Vickery, S. et al. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and amino-terminal proBNP in patients with CKD: relationship to renal function and left ventricular hypertrophy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 46, 610–620 (2005).

Tang, W. H. W. et al. Usefulness of plasma galectin-3 levels in systolic heart failure to predict renal insufficiency and survival. Am. J. Cardiol. 108, 385–390 (2011).

Evenepoel, P., D'Haese, P. & Brandenburg, V. Sclerostin and DKK1: new players in renal bone and vascular disease. Kidney Int. 88, 235–240 (2015).

Ketteler, M. et al. Revisiting KDIGO clinical practice guideline on chronic kidney disease — mineral and bone disorder: a commentary from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes controversies conference. Kidney Int. 87, 502–528 (2015).

Zoccali, C. et al. The complexity of the cardio–renal link: taxonomy, syndromes, and diseases. Kidney Int. Suppl. 1, 2–5 (2011).

Cozzolino, M. et al. Is chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD) really a syndrome? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 29, 1815–1820 (2014).

Brigandt, I. & Love, A. in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (ed. Zalta, E. N.) (Stanford Univ., 2017).

Macdougall, I. C. et al. Beyond the cardiorenal anaemia syndrome: recognizing the role of iron deficiency. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 14, 882–886 (2012).

Beresford, M. J. Medical reductionism: lessons from the great philosophers. QJM 103, 721–724 (2010).

Hektoen International. Richard Bright, the father of nephrology. HekInt.orghttp://www.hektoeninternational.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=705 (2013).

Seldin, D. W., Carter, N. W. & Rector, F. C. in Strauss and Welt's Diseases of the Kidney Vol. 2 (eds Strauss, M. B. & Welt, L. G.) 211–272 (Little Brown Co.,1971).

Straub, R. H., Cutolo, M., Buttgereit, F. & Pongratz, G. Energy regulation and neuroendocrine-immune control in chronic inflammatory diseases. J. Intern. Med. 267, 543–560 (2010).

Manning, P. J. et al. Postprandial cytokine concentrations and meal composition in obese and lean women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16, 2046–2052 (2008).

Walford, R. L., Harris, S. B. & Gunion, M. W. The calorically restricted low-fat nutrient-dense diet in Biosphere 2 significantly lowers blood glucose, total leukocyte count, cholesterol, and blood pressure in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 11533–11537 (1992).

Maciver, N. J. et al. Glucose metabolism in lymphocytes is a regulated process with significant effects on immune cell function and survival. J. Leukoc. Biol. 84, 949–957 (2008).

Frauwirth, K. A. & Thompson, C. B. Regulation of T lymphocyte metabolism. J. Immunol. 172, 4661–4665 (2004).

Mauvais-Jarvis, F. Estrogen and androgen receptors: regulators of fuel homeostasis and emerging targets for diabetes and obesity. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 22, 24–33 (2011).

Ducy, P. The role of osteocalcin in the endocrine cross-talk between bone remodelling and energy metabolism. Diabetologia 54, 1291–1297 (2011).

Moore, M. C. et al. Effect of hepatic denervation on peripheral insulin sensitivity in conscious dogs. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 282, E286–E296 (2002).

Christiansen, J. J. et al. Effects of cortisol on carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism: studies of acute cortisol withdrawal in adrenocortical failure. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 3553–3559 (2009).

Jones, B. J., Tan, T. & Bloom, S. R. Minireview: glucagon in stress and energy homeostasis. Endocrinology 153, 1049–1054 (2012).

Báez-Pagán, C. A., Delgado-Vélez, M. & Lasalde-Dominicci, J. A. Activation of the macrophage α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and control of inflammation. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 10, 468–476 (2015).

Andersson, U. & Tracey, K. J. Neural reflexes in inflammation and immunity. J. Exp. Med. 209, 1057–1068 (2012).

Scherrer, U. & Sartori, C. Insulin as a vascular and sympathoexcitatory hormone: implications for blood pressure regulation, insulin sensitivity, and cardiovascular morbidity. Circulation 96, 4104–4113 (1997).

Rui, L. Energy metabolism in the liver. Compr. Physiol. 4, 177–197 (2014).

Härle, P., Möbius, D., Carr, D. J. J., Schölmerich, J. & Straub, R. H. An opposing time-dependent immune-modulating effect of the sympathetic nervous system conferred by altering the cytokine profile in the local lymph nodes and spleen of mice with type II collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 52, 1305–1313 (2005).

Mehrotra, R. et al. Serum fetuin-A in nondialyzed patients with diabetic nephropathy: relationship with coronary artery calcification. Kidney Int. 67, 1070–1077 (2005).

Gupta, J. et al. Association between albuminuria, kidney function, and inflammatory biomarker profile in CKD in CRIC. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 7, 1938–1946 (2012).

Cottone, S. et al. Relationship of fetuin-A with glomerular filtration rate and endothelial dysfunction in moderate–severe chronic kidney disease. J. Nephrol. 23, 62–69 (2010).

Stenvinkel, P. & Larsson, T. E. Chronic kidney disease: a clinical model of premature aging. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 62, 339–351 (2013).

Schindler, R. Causes and therapy of microinflammation in renal failure. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 19, 34–40 (2004).

Levey, A. S. et al. Chronic kidney disease as a global public health problem: approaches and initiatives — a position statement from Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. Kidney Int. 72, 247–259 (2007).

Akar, H., Akar, G. C., Carrero, J. J., Stenvinkel, P. & Lindholm, B. Systemic consequences of poor oral health in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 6, 218–226 (2011).

Locatelli, F. et al. Oxidative stress in end-stage renal disease: an emerging threat to patient outcome. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 18, 1272–1280 (2003).

Gardner, S. E., Humphry, M., Bennett, M. R. & Clarke, M. C. H. Senescent vascular smooth muscle cells drive inflammation through an interleukin-1α-dependent senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35, 1963–1974 (2015).

Carrero, J. J. et al. Low serum testosterone increases mortality risk among male dialysis patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 613–620 (2009).

Vlassara, H. et al. Role of oxidants/inflammation in declining renal function in chronic kidney disease and normal aging. Kidney Int. Suppl. 76, S3–S11 (2009).

Sun, C.-Y., Hsu, H.-H. & Wu, M.-S. p-Cresol sulfate and indoxyl sulfate induce similar cellular inflammatory gene expressions in cultured proximal renal tubular cells. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 28, 70–78 (2013).

Rao, A. K. et al. Left atrial volume is associated with inflammation and atherosclerosis in patients with kidney disease. Echocardiography 25, 264–269 (2008).

de Nadai, T. R. et al. Metabolic acidosis treatment as part of a strategy to curb inflammation. Int. J. Inflam. 2013, 601424 (2013).

Viaene, L. et al. Inflammation and the bone–vascular axis in end-stage renal disease. Osteoporos. Int. 27, 489–497 (2016).

Aghagolzadeh, P. et al. Calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells is induced by secondary calciprotein particles and enhanced by tumor necrosis factor-α. Atherosclerosis 251, 404–414 (2016).

Underwood, C. F. et al. Uraemia: an unrecognized driver of central neurohumoral dysfunction in chronic kidney disease? Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 219, 305–323 (2016).

Thomas, S. S., Zhang, L. & Mitch, W. E. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 88, 1233–1239 (2015).

Meyring-Wösten, A. et al. Intradialytic hypoxemia and clinical outcomes in patients on hemodialysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11, 616–625 (2016).

Spoto, B. et al. Association of IL-6 and a functional polymorphism in the IL-6 gene with cardiovascular events in patients with CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 232–240 (2015).

Stenvinkel, P. et al. Impact of inflammation on epigenetic DNA methylation — a novel risk factor for cardiovascular disease? J. Intern. Med. 261, 488–499 (2007).

Silva, J. E. Thyroid hormone control of thermogenesis and energy balance. Thyroid 5, 481–492 (1995).

Zoccali, C., Tripepi, G., Cutrupi, S., Pizzini, P. & Mallamaci, F. Low triiodothyronine: a new facet of inflammation in end-stage renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 2789–2795 (2005).

Meuwese, C. L., Dekkers, O. M., Stenvinkel, P., Dekker, F. W. & Carrero, J. J. Nonthyroidal illness and the cardiorenal syndrome. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 9, 599–609 (2013).

Levick, S. P., Murray, D. B., Janicki, J. S. & Brower, G. L. Sympathetic nervous system modulation of inflammation and remodeling in the hypertensive heart. Hypertension 55, 270–276 (2010).

Mafra, D. et al. Role of altered intestinal microbiota in systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. Future Microbiol. 9, 399–410 (2014).

Koppe, L., Mafra, D. & Fouque, D. Probiotics and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 88, 1–9 (2015).

Holzer, P. & Farzi, A. Neuropeptides and the microbiota–gut–brain axis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 817, 195–219 (2014).

Lai, H. L., Kartal, J. & Mitsnefes, M. Hyperinsulinemia in pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease: the role of tumor necrosis factor-α. Pediatr. Nephrol. 22, 1751–1756 (2007).

Landau, M. et al. Correlates of insulin resistance in older individuals with and without kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 26, 2814–2819 (2011).

Mallamaci, F., Tripepi, G. & Zoccali, C. Leptin in end stage renal disease (ESRD): a link between fat mass, bone and the cardiovascular system. J. Nephrol. 18, 464–468 (2005).

Yoo, D. E. et al. Low circulating adiponectin levels are associated with insulin resistance in non-obese peritoneal dialysis patients. Endocr. J. 59, 685–695 (2012).

Landsberg, L. & Young, J. B. Fasting, feeding and regulation of the sympathetic nervous system. N. Engl. J. Med. 298, 1295–1301 (1978).

Yano, Y. et al. Synergistic effect of chronic kidney disease and high circulatory norepinephrine level on stroke risk in Japanese hypertensive patients. Atherosclerosis 219, 273–279 (2011).

Fouque, D. et al. A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein-energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 73, 391–398 (2008).

Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Ikizler, T. A., Block, G., Avram, M. M. & Kopple, J. D. Malnutrition–inflammation complex syndrome in dialysis patients: causes and consequences. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 42, 864–881 (2003).

Gupta, J. et al. Association between inflammation and cardiac geometry in chronic kidney disease: findings from the CRIC study. PLoS ONE 10, e0124772 (2015).

Zoccali, C. et al. Fibrinogen, inflammation and concentric left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic renal failure. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 33, 561–566 (2003).

Zoccali, C. et al. Norepinephrine and concentric hypertrophy in patients with end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 40, 41–46 (2002).

Zoccali, C. et al. Neuropeptide Y, left ventricular mass and function in patients with end stage renal disease. J. Hypertens. 21, 1355–1362 (2003).

Zoccali, C. et al. Plasma norepinephrine predicts survival and incident cardiovascular events in patients with end-stage renal disease. Circulation 105, 1354–1359 (2002).

Zoccali, C. et al. Prospective study of neuropeptide Y as an adverse cardiovascular risk factor in end-stage renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 2611–2617 (2003).

Eltzschig, H. K. & Carmeliet, P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 656–665 (2011).

O'Riordan, E. et al. Chronic NOS inhibition actuates endothelial–mesenchymal transformation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292, H285–H294 (2007).

Kang, D.-H. et al. Role of the microvascular endothelium in progressive renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 806–816 (2002).

Tanaka, T. & Nangaku, M. Angiogenesis and hypoxia in the kidney. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 9, 211–222 (2013).

Hussain, S. et al. Outcome among patients with acute renal failure needing continuous renal replacement therapy: a single center study. Hemodial. Int. 13, 205–214 (2009).

Bollée, G. et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy secondary to VEGF pathway inhibition by sunitinib. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 24, 682–685 (2009).

Massy, Z. A., Stenvinkel, P. & Drueke, T. B. The role of oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Semin. Dial. 22, 405–408 (2009).

Kapitsinou, P. P. & Haase, V. H. Molecular mechanisms of ischemic preconditioning in the kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 309, F821–F834 (2015).

Tanaka, T. Expanding roles of the hypoxia-response network in chronic kidney disease. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 20, 835–844 (2016).

Tanaka, T., Yamaguchi, J., Higashijima, Y. & Nangaku, M. Indoxyl sulfate signals for rapid mRNA stabilization of Cbp/p300-interacting transactivator with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain 2 (CITED2) and suppresses the expression of hypoxia-inducible genes in experimental CKD and uremia. FASEB J. 27, 4059–4075 (2013).

Sun, C.-Y., Chang, S.-C. & Wu, M.-S. Suppression of Klotho expression by protein-bound uremic toxins is associated with increased DNA methyltransferase expression and DNA hypermethylation. Kidney Int. 81, 640–650 (2012).

Deng, A. et al. Renal protection in chronic kidney disease: hypoxia-inducible factor activation versus angiotensin II blockade. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 299, F1365–F1373 (2010).

Maxwell, P. H. & Eckardt, K.-U. HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors for the treatment of renal anaemia and beyond. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 12, 157–168 (2015).

Munoz Mendoza, J. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and Inflammation in CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 7, 1155–1162 (2012).

Fliser, D. et al. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are already present in patients with incipient renal disease. Kidney Int. 53, 1343–1347 (1998).

de Boer, I. H. et al. Impaired glucose and insulin homeostasis in moderate–severe CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 2861–2871 (2016).

DeFronzo, R. A. et al. Insulin resistance in uremia. J. Clin. Invest. 67, 563–568 (1981).

Schenk, S., Saberi, M. & Olefsky, J. M. Insulin sensitivity: modulation by nutrients and inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 2992–3002 (2008).

Djiogue, S. et al. Insulin resistance and cancer: the role of insulin and IGFs. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 20, R1–R17 (2013).

Giles, J. T. et al. Insulin resistance in rheumatoid arthritis: disease-related indicators and associations with the presence and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 626–636 (2015).

Hotamisligil, G. S. et al. IRS-1-mediated inhibition of insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity in TNF-alpha- and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Science 271, 665–668 (1996).

Senn, J. J., Klover, P. J., Nowak, I. A. & Mooney, R. A. Interleukin-6 induces cellular insulin resistance in hepatocytes. Diabetes 51, 3391–3399 (2002).

Yadav, A., Kataria, M. A., Saini, V. & Yadav, A. Role of leptin and adiponectin in insulin resistance. Clin. Chim. Acta 417, 80–84 (2013).

Muse, E. D. et al. Role of resistin in diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 232–239 (2004).

Straub, R. H. & Besedovsky, H. O. Integrated evolutionary, immunological, and neuroendocrine framework for the pathogenesis of chronic disabling inflammatory diseases. FASEB J. 17, 2176–2183 (2003).

Straub, R. H. & Schradin, C. Chronic inflammatory systemic diseases: an evolutionary trade-off between acutely beneficial but chronically harmful programs. Evol. Med. Public Health 2016, 37–51 (2016).

He, J. et al. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion and CKD progression. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 1202–1212 (2015).

Mills, K. T. et al. Sodium excretion and the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA 315, 2200–2210 (2016).

Rodríguez-Iturbe, B., Vaziri, N. D., Herrera-Acosta, J. & Johnson, R. J. Oxidative stress, renal infiltration of immune cells, and salt-sensitive hypertension: all for one and one for all. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 286, F606–F616 (2004).

Schatz, V. et al. Elementary immunology: Na+ as a regulator of immunity. Pediatr. Nephrol. 32, 201–210 (2016).

Machnik, A. et al. Macrophages regulate salt-dependent volume and blood pressure by a vascular endothelial growth factor-C-dependent buffering mechanism. Nat. Med. 15, 545–552 (2009).

Lee, N. K. An evolving integrative physiology: skeleton and energy metabolism. BMB Rep. 43, 579–583 (2010).

Amanzadeh, J. & Reilly, R. F. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based approach to its clinical consequences and management. Nat. Clin. Pract. Nephrol. 2, 136–148 (2006).

Tonelli, M. et al. Relation between serum phosphate level and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation 112, 2627–2633 (2005).

Faul, C. et al. FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4393–4408 (2011).

Ferron, M. & Lacombe, J. Regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton: osteocalcin and beyond. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 561, 137–146 (2014).

Lee, N. K. et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell 130, 456–469 (2007).

Rix, M., Andreassen, H., Eskildsen, P., Langdahl, B. & Olgaard, K. Bone mineral density and biochemical markers of bone turnover in patients with predialysis chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 56, 1084–1093 (1999).

Hinoi, E. et al. The sympathetic tone mediates leptin's inhibition of insulin secretion by modulating osteocalcin bioactivity. J. Cell Biol. 183, 1235–1242 (2008).

Hong, S.-H. et al. Changes in serum osteocalcin are not associated with changes in glucose or insulin for osteoporotic patients treated with bisphosphonate. J. Bone Metab. 20, 37–41 (2013).

Schwartz, A. V. et al. Effects of antiresorptive therapies on glucose metabolism: results from the FIT, HORIZON-PFT, and FREEDOM trials. J. Bone Miner. Res. 28, 1348–1354 (2013).

Vervloet, M. G. et al. Bone: a new endocrine organ at the heart of chronic kidney disease and mineral and bone disorders. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2, 427–436 (2014).

Holden, R. M. et al. Vitamins K and D status in stages 3–5 chronic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 5, 590–597 (2010).

McCabe, K. M. et al. Dietary vitamin K and therapeutic warfarin alter the susceptibility to vascular calcification in experimental chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 83, 835–844 (2013).

Okuno, S. et al. Significant inverse relationship between serum undercarboxylated osteocalcin and glycemic control in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Osteoporos. Int. 24, 605–612 (2013).

Patterson-Buckendahl, P. Osteocalcin is a stress-responsive neuropeptide. Endocr. Regul. 45, 99–110 (2011).

Kawai, M., Kinoshita, S., Shimba, S., Ozono, K. & Michigami, T. Sympathetic activation induces skeletal Fgf23 expression in a circadian rhythm-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 1457–1466 (2014).

Grabner, A. et al. Activation of cardiac fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 causes left ventricular hypertrophy. Cell Metab. 22, 1020–1032 (2015).

Gutiérrez, O. M. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Circulation 119, 2545–2552 (2009).

Dai, B. et al. A comparative transcriptome analysis identifying FGF23 regulated genes in the kidney of a mouse CKD model. PLoS ONE 7, e44161 (2012).

Wojcik, M. et al. The association of FGF23 levels in obese adolescents with insulin sensitivity. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 25, 687–690 (2012).

Mirza, M. A. I. et al. Circulating fibroblast growth factor-23 is associated with fat mass and dyslipidemia in two independent cohorts of elderly individuals. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31, 219–227 (2011).

Scialla, J. J. et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and cardiovascular events in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 25, 349–360 (2014).

Xie, J., Yoon, J., An, S.-W., Kuro-o, M. & Huang, C.-L. Soluble klotho protects against uremic cardiomyopathy independently of fibroblast growth factor 23 and phosphate. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 1150–1160 (2015).

Fliser, D. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) predicts progression of chronic kidney disease: the Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease (MMKD) Study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 2600–2608 (2007).

Scialla, J. J. et al. Mineral metabolites and CKD progression in African Americans. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24, 125–135 (2013).

Tripepi, G. et al. Competitive interaction between fibroblast growth factor 23 and asymmetric dimethylarginine in patients with CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 1–10 (2014).

Sanz, A. B. et al. TWEAK and the progression of renal disease: clinical translation. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 29 (Suppl. 1), i54–i62 (2014).

David, V. et al. Inflammation and functional iron deficiency regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 production. Kidney Int. 89, 135–146 (2015).

Dounousi, E. et al. Intact FGF23 and αklotho during acute inflammation/sepsis in CKD patients. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 46, 234–241 (2016).

Rossaint, J. et al. FGF23 signaling impairs neutrophil recruitment and host defense during CKD. 126, 962–974 (2016).

Silswal, N. et al. FGF23 directly impairs endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation by increasing superoxide levels and reducing nitric oxide bioavailability. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 307, E426–E436 (2014).

Dounousi, E. et al. Effect of inflammation by acute sepsis on intact fibroblast growth factor 23 (iFGF23) and asymmetric dimethyl arginine (ADMA) in ckd patients. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 26, 80–83 (2015).

Lopez, A. et al. Multiple-center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor 546C88: effect on survival in patients with septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 32, 21–30 (2004).

London, G. M., Marchais, S. J., Guérin, A. P. & de Vernejoul, M.-C. Ankle–brachial index and bone turnover in patients on dialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 1–8 (2014).

Ng, K. W. Regulation of glucose metabolism and the skeleton. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 75, 147–155 (2011).

Zoccali, C. et al. Leptin and biochemical markers of bone turnover in dialysis patients. J. Nephrol. 17, 253–260 (2004).

Grgurevic, L., Christensen, G. L., Schulz, T. J. & Vukicevic, S. Bone morphogenetic proteins in inflammation, glucose homeostasis and adipose tissue energy metabolism. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 27, 105–118 (2016).

Luttropp, K. et al. Genotypic and phenotypic predictors of inflammation in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 31, 2033–2040 (2016).

Li, X., Yang, H.-Y. & Giachelli, C. M. BMP-2 promotes phosphate uptake, phenotypic modulation, and calcification of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis 199, 271–277 (2008).

Smith, E. R. et al. Phosphorylated fetuin-A-containing calciprotein particles are associated with aortic stiffness and a procalcific milieu in patients with pre-dialysis CKD. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 27, 1957–1966 (2012).

Muñoz-Félix, J. M., González-Núñez, M., Martínez-Salgado, C. & López-Novoa, J. M. TGF-β/BMP proteins as therapeutic targets in renal fibrosis. Where have we arrived after 25 years of trials and tribulations? Pharmacol. Ther. 156, 44–58 (2015).

Massy, Z. A. & Drueke, T. B. Activin receptor IIA ligand trap in chronic kidney disease: 1 drug to prevent 2 complications-or even more? Kidney Int. 89, 1180–1182 (2016).