Abstract

Antipsychotic medications can induce cardiovascular and metabolic abnormalities (such as obesity, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia and the metabolic syndrome) that are associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Controversy remains about the contribution of individual antipsychotic drugs to this increased risk and whether they cause sudden cardiac death through prolongation of the corrected QT interval. Although some drug receptor-binding affinities correlate with specific cardiovascular and metabolic abnormalities, the exact pharmacological mechanisms underlying these associations remain unclear. Antipsychotic agents with prominent metabolic adverse effects might cause abnormalities in glucose and lipid metabolism via both obesity-related and obesity-unrelated molecular mechanisms. Despite existing guidelines and recommendations, many antipsychotic-drug-treated patients are not assessed for even the most easily measurable metabolic and cardiac risk factors, such as obesity and blood pressure. Subsequently, concerns have been raised over the use of these medications, especially pronounced in vulnerable pediatric patients, among whom their use has increased markedly in the past decade and seems to have especially orexigenic effects. This Review outlines the metabolic and cardiovascular risks of various antipsychotic medications in adults and children, defines the disparities in health care and finally makes recommendations for screening and monitoring of patients taking these agents.

Key Points

-

Although all antipsychotic drugs can induce cardiovascular and metabolic dysfunction (especially in drug-naive, first-episode and pediatric populations), olanzapine and clozapine are most likely to cause such adverse effects

-

Drug affinities for histamine, dopamine, serotonin and muscarinic receptors are closely linked to cardiovascular risk accumulation and metabolic dysfunction, but the exact underlying pharmacological mechanisms remain to be elucidated

-

Abnormalities in glucose and lipid metabolism often occur via increased abdominal adiposity; however, antipsychotic drugs associated with pronounced metabolic adverse effects can also have a direct molecular effect

-

Patients with a history of heart disease, arrhythmia, or syncope, or a family history of prolonged QT syndrome or early sudden cardiac death should not receive QT-prolonging antipsychotic drugs

-

Monitoring cardiovascular risk is insufficient; patients' weight, blood pressure and fasting glucose and lipids should be assessed routinely, and, if possible, every patient should undergo electrocardiography before initiation of antipsychotic treatment

-

Healthy diet, regular exercise and smoking cessation reduce patients' cardiovascular and metabolic risk; low-risk antipsychotic agents, adding weight-lowering medications and/or treating significant cardiovascular and metabolic abnormalities might also help

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Tandon, R., Nasrallah, H. A. & Keshavan, M. S. Schizophrenia, “just the facts” 5. Treatment and prevention. Past, present, and future. Schizophr. Res. 122, 1–23 (2010).

Comer, J. S., Olfson, M. & Mojtabai, R. National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996–2007. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 49, 1001–1010 (2010).

De Hert, M., Dobbelaere, M., Sheridan, E. M., Cohen, D. & Correll, C. U. Metabolic and endocrine adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized, placebo controlled trials and guidelines for clinical practice. Eur. Psychiatry 26, 144–158 (2011).

Mojtabai, R. & Olfson, M. National trends in psychotropic medication polypharmacy in office-based psychiatry. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 26–36 (2010).

Kane, J. M. & Correll, C. U. Past and present progress in the pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 79, 1115–1124 (2010).

Leucht, S., Arbter, D., Engel, R. R., Kissling, W. & Davis, J. M. How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Mol. Psychiatry 14, 429–447 (2009).

Leucht, S. et al. A meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 166, 152–163 (2009).

Leucht, S. et al. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet 373, 31–41 (2009).

Rummel-Kluge, C. et al. Second-generation antipsychotic drugs and extrapyramidal side effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons. Schizophr. Bull. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbq042.

Maayan, L., Vakhrusheva, J. & Correll, C. U. Effectiveness of medications used to attenuate antipsychotic-related weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 1520–1530 (2010).

Correll, C. U., Lencz, T. & Malhotra, A. K. Antipsychotic drugs and obesity. Trends Mol. Med. 17, 97–107 (2011).

Morrato, E. H. et al. Metabolic testing rates in 3 state Medicaid programs after FDA warnings and ADA/APA recommendations for second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 17–24 (2010).

Morrato, E. H. et al. Metabolic screening in children receiving antipsychotic drug treatment. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 164, 344–351 (2010).

Mitchell, A. J., Delaffon, V., Vancampfort, D., Correll, C. U. & De Hert, M. Guideline concordant monitoring of metabolic risk in people treated with antipsychotic medication: systematic review and meta-analysis of screening practices. Psychol. Med. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S003329171100105X.

Maina, G., Salvi, V., Vitalucci, A., D'Ambrosio, V. & Bogetto, F. Prevalence and correlates of overweight in drug-naïve patients with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 110, 149–155 (2008).

De Hert, M. et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry 10, 52–77 (2011).

van Winkel, R. et al. Psychiatric diagnosis as an independent risk factor for metabolic disturbances: results from a comprehensive, naturalistic screening program. J. Clin. Psychiatry 69, 1319–1327 (2008).

van Winkel, R. et al. Prevalence of diabetes and the metabolic syndrome in a sample of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 10, 342–348 (2008).

Parsons, B. et al. Weight effects associated with antipsychotics: a comprehensive database analysis. Schizophr. Res. 110, 103–110 (2009).

Coccurello, R. & Moles, A. Potential mechanisms of atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic derangement: clues for understanding obesity and novel drug design. Pharmacol. Ther. 127, 210–251 (2010).

Kahn, R. S. et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet 371, 1085–1097 (2008).

Newcomer, J. W. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs 19 (Suppl. 1), 1–93 (2005).

Lieberman, J. A. et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1209–1223 (2005).

Citrome, L. Risk–benefit analysis of available treatments for schizophrenia. Psychiatric Times 1, 27–30 (2007).

Tarricone, I., Ferrari Gozzi, B., Serretti, A., Grieco, D. & Berardi, D. Weight gain in antipsychotic-naive patients: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 40, 187–200 (2010).

Alvarez-Jiménez, M. et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain in chronic and first-episode psychotic disorders: a systematic critical reappraisal. CNS Drugs 22, 547–562 (2008).

Strassnig, M., Miewald, J., Keshavan, M. & Ganguli, R. Weight gain in newly diagnosed first-episode psychosis patients and healthy comparisons: one-year analysis. Schizophr. Res. 93, 90–98 (2007).

Correll, C. U. et al. Recognizing and monitoring adverse events of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 15, 177–206 (2006).

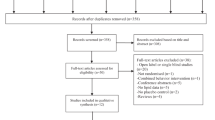

Mitchell, A. J., Vancampfort, D., Sweers, K., van Winkel, R. & De Hert, M. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders—a PRISMA meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. (in press).

Correll, C. U. et al. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA 302, 1765–1773 (2009).

Correll, C. U., Sheridan, E. M. & DelBello, M. P. Antipsychotic and mood stabilizer efficacy and tolerability in pediatric and adult patients with bipolar I mania: a comparative analysis of acute, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord. 12, 116–141 (2010).

Fraguas, D. et al. Efficacy and safety of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents with psychotic and bipolar spectrum disorders: Comprehensive review of prospective head-to-head and placebo-controlled comparisons. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21, 621–645 (2011).

McIntyre, R. S. & Jerrell, J. M. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse events associated with antipsychotic treatment in children and adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 162, 929–935 (2008).

Jerrell, J. M. & McIntyre, R. S. Adverse events in children and adolescents treated with antipsychotic medications. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 23, 283–290 (2008).

Reynolds, G. P. & Kirk, S. L. Metabolic side effects of antipsychotic drug treatment—pharmacological mechanisms. Pharmacol. Ther. 125, 169–179 (2010).

Zyprexa® (olanzapine) prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company [online], (2011).

Bhargava, A. A longitudinal analysis of the risk factors for diabetes and coronary heart disease in the Framingham Offspring Study. Popul. Health. Metr. 1, 3 (2003).

Grundy, S. M. Metabolic syndrome: connecting and reconciling cardiovascular and diabetes worlds. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 1093–1100 (2006).

Arango, C. et al. A comparison of schizophrenia outpatients treated with antipsychotics with and without metabolic syndrome: Findings from the CLAMORS study. Schizophr. Res. 104, 1–12 (2008).

Foley, D. L. & Morley, K. I. Systematic review of early cardiometabolic outcomes of the first treated episode of psychosis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 609–616 (2011).

De Hert, M. et al. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Psychiatry 24, 412–424 (2009).

Nielsen, J., Skadhede, S. & Correll, C. U. Antipsychotics associated with the development of type 2 diabetes in antipsychotic-naive schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 1997–2004 (2010).

American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. J. Clin. Psychiatry 65, 267–272 (2004).

Kessing, L. V., Thomsen, A. F., Mogensen, U. B. & Andersen, P. K. Treatment with antipsychotics and the risk of diabetes in clinical practice. Br. J. Psychiatry 197, 266–271 (2010).

Simon, V., van Winkel, R. & De Hert, M. Are weight gain and metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics dose dependent? A literature review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70, 1041–1050 (2009).

Rummel-Kluge, C. et al. Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 123, 225–233 (2010).

De Hert, M., Schreurs, V., Vancampfort, D. & Van Winkel, R. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: a review. World Psychiatry 8, 15–22 (2009).

Vancampfort, D. et al. Relationships between obesity, functional exercise capacity, physical activity participation and physical self-perception in people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 123, 423–430 (2011).

Vancampfort, D. et al. Considering a frame of reference for physical activity research related to the cardiometabolic risk profile in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 177, 271–279 (2010).

Qin, L., Knol, M. J., Corpeleijn, E. & Stolk, R. P. Does physical activity modify the risk of obesity for type 2 diabetes: a review of epidemiological data. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 5–12 (2010).

Hartemink, N., Boshuizen, H. C., Nagelkerke, N. J., Jacobs, M. A. & van Houwelingen, H. C. Combining risk estimates from observational studies with different exposure cutpoints: a meta-analysis on body mass index and diabetes type 2. Am. J. Epidemiol. 163, 1042–1052 (2006).

Alberti, K. G., Zimmet, P. & Shaw, J. International Diabetes Federation: a consensus on type 2 diabetes prevention. Diabet. Med. 24, 451–463 (2007).

Smith, M. et al. First- versus second-generation antipsychotics and risk for diabetes in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 192, 406–411 (2008).

Liao, C. H. et al. Schizophrenia patients at higher risk of diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia: a population-based study. Schizophr. Res. 126, 110–116 (2011).

Ramaswamy, K., Masand, P. S. & Nasrallah, H. A. Do certain atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of diabetes? A critical review of 17 pharmacoepidemiologic studies. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 18, 183–194 (2006).

Yood, M. U. et al. The incidence of diabetes in atypical antipsychotic users differs according to agent—results from a multisite epidemiologic study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 18, 791–799 (2009).

Starrenburg, F. C. & Bogers, J. P. How can antipsychotics cause diabetes mellitus? Insights based on receptor-binding profiles, humoral factors and transporter proteins. Eur. Psychiatry 24, 164–170 (2009).

Baker, R. A. et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and diabetes mellitus in the US Food and Drug Administration adverse event database: a systematic Bayesian signal detection analysis. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 42, 11–31 (2009).

Bushe, C. J. & Leonard, B. E. Blood glucose and schizophrenia: a systematic review of prospective randomized clinical trials. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68, 1682–1690 (2007).

Hammerman, A. et al. Antipsychotics and diabetes: an age-related association. Ann. Pharmacother. 42, 1316–1322 (2008).

Panagiotopoulos, C., Ronsley, R. & Davidson, J. Increased prevalence of obesity and glucose intolerance in youth treated with second-generation antipsychotic medications. Can. J. Psychiatry 54, 743–749 (2009).

Kim, S. F., Huang, A. S., Snowman, A. M., Teuscher, C. & Snyder, S. H. From the cover: Antipsychotic drug-induced weight gain mediated by histamine H1 receptor-linked activation of hypothalamic AMP-kinase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3456–3459 (2007).

Kroeze, W. K. et al. H1-histamine receptor affinity predicts short-term weight gain for typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs. Neuropsychopharmacology 28, 519–526 (2003).

Correll, C. U. From receptor pharmacology to improved outcomes: individualizing the selection, dosing, and switching of antipsychotics. Eur. Psychiatry 25 (Suppl. 2), S12–S21 (2010).

Johnson, D. E. et al. The role of muscarinic receptor antagonism in antipsychotic-induced hippocampal acetylcholine release. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 506, 209–219 (2005).

Silvestre, J. S. & Prous, J. Research on adverse drug events. I. Muscarinic M3 receptor binding affinity could predict the risk of antipsychotics to induce type 2 diabetes. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 27, 289–304 (2005).

Bishara, D. & Taylor, D. Asenapine monotherapy in the acute treatment of both schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 5, 483–490 (2009).

Moons, T. et al. Clock genes and body composition in patients with schizophrenia under treatment with antipsychotic drugs. Schizophr. Res. 125, 187–193 (2011).

van Winkel, R. et al. MTHFR and risk of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 121, 193–198 (2010).

van Winkel, R. et al. MTHFR genotype and differential evolution of metabolic parameters after initiation of a second generation antipsychotic: an observational study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 25, 270–276 (2010).

Balt, S. L., Galloway, G. P., Baggott, M. J., Schwartz, Z. & Mendelson, J. Mechanisms and genetics of antipsychotic-associated weight gain. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 90, 179–183 (2011).

Nasrallah, H. A. Atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: insights from receptor-binding profiles. Mol. Psychiatry 13, 27–35 (2008).

Oh, K. J. et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs perturb AMPK-dependent regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 300, E624–E632 (2011).

Hennessy, S. et al. Cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia in patients taking antipsychotic drugs: cohort study using administrative data. BMJ 325, 1070 (2002).

Straus, S. M. et al. Antipsychotics and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Arch. Intern. Med. 164, 1293–1297 (2004).

Ray, W. A., Chung, C. P., Murray, K. T., Hall, K. & Stein, C. M. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 225–235 (2009).

Manu, P., Kane, J. M. & Correll, C. U. Sudden deaths in psychiatric patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry 72, 936–941 (2011).

Haddad, P. M. & Sharma, S. G. Adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics; differential risk and clinical implications. CNS Drugs 21, 911–936 (2007).

Elbe, D. & Savage, R. How does this happen? Part I: mechanisms of adverse drug reactions associated with psychotropic medications. J. Can. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 19, 40–45 (2010).

Reilly, J. G., Ayis, S. A., Ferrier, I. N., Jones, S. J. & Thomas, S. H. Thioridazine and sudden unexplained death in psychiatric in-patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 180, 515–522 (2002).

Thomas, S. H. et al. Safety of sertindole versus risperidone in schizophrenia: principal results of the sertindole cohort prospective study (SCoP). Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 122, 345–355 (2010).

Strom, B. L. et al. Comparative mortality associated with ziprasidone and olanzapine in real-world use among 18,154 patients with schizophrenia: The Ziprasidone Observational Study of Cardiac Outcomes (ZODIAC). Am. J. Psychiatry 168, 193–201 (2011).

Correll, C. U. & Nielsen, J. Antipsychotic-associated all-cause and cardiac mortality: what should we worry about and how should the risk be assessed? Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 122, 341–344 (2010).

Barnes, T. R. et al. A UK audit of screening for the metabolic side effects of antipsychotics in community patients. Schizophr. Bull. 33, 1397–1403 (2007).

Lambert, T. J. & Newcomer, J. W. Are the cardiometabolic complications of schizophrenia still neglected? Barriers to care. Med. J. Aust. 190, S39–S42 (2009).

Hasnain, M., Fredrickson, S. K., Vieweg, W. V. & Pandurangi, A. K. Metabolic syndrome associated with schizophrenia and atypical antipsychotics. Curr. Diab. Rep. 10, 209–216 (2010).

Haupt, D. W. et al. Prevalence and predictors of lipid and glucose monitoring in commercially insured patients treated with second-generation antipsychotic agents. Am. J. Psychiatry 166, 345–353 (2009).

Kisely, S., Campbell, L. A. & Wang, Y. Treatment of ischaemic heart disease and stroke in individuals with psychosis under universal healthcare. Br. J. Psychiatry 195, 545–550 (2009).

Kisely, S. et al. Inequitable access for mentally ill patients to some medically necessary procedures. CMAJ 176, 779–784 (2007).

Laursen, T. M., Munk-Olsen, T., Agerbo, E., Gasse, C. & Mortensen, P. B. Somatic hospital contacts, invasive cardiac procedures, and mortality from heart disease in patients with severe mental disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 713–720 (2009).

Wheeler, A. J. et al. Cardiovascular risk assessment and management in mental health clients: whose role is it anyway? Community Ment. Health J. 46, 531–539 (2010).

Nasrallah, H. A. et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr. Res. 86, 15–22 (2006).

De Hert, M. et al. The METEOR study of diabetes and other metabolic disorders in patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotic drugs. I. Methodology. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 19, 195–210 (2010).

Kilbourne, A. M., Welsh, D., McCarthy, J. F., Post, E. P. & Blow, F. C. Quality of care for cardiovascular disease-related conditions in patients with and without mental disorders. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 23, 1628–1633 (2008).

Raedler, T. J. Cardiovascular aspects of antipsychotics. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 23, 574–581 (2010).

Hippisley-Cox, J., Parker, C., Coupland, C. & Vinogradova, Y. Inequalities in the primary care of patients with coronary heart disease and serious mental health problems: a cross-sectional study. Heart 93, 1256–1262 (2007).

Hennekens, C. H., Hennekens, A. R., Hollar, D. & Casey, D. E. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am. Heart J. 150, 1115–1121 (2005).

Fagiolini, A. & Goracci, A. The effects of undertreated chronic medical illnesses in patients with severe mental disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70, 22–29 (2009).

Wahrenberg, H. et al. Use of waist circumference to predict insulin resistance: retrospective study. BMJ 330, 1363–1364 (2005).

Straker, D. et al. Cost-effective screening for the metabolic syndrome in patients treated with second-generation antipsychotic medications. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 1217–1221 (2005).

Ness-Abramof, R. & Apovian, C. M. Waist circumference measurement in clinical practice. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 23, 397–404 (2008).

Alberti, K. G. et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 120, 1640–1645 (2009).

Chobanian, A. V. et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 289, 2560–2572 (2003).

International Expert Committee. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 32, 1327–1334 (2009).

Manu, P., Correll, C. U., van Winkel, R., Wampers, M. & De Hert, M. Prediabetes in patients treated with antipsychotic drugs. J. Clin. Psychiatry (in press).

Fan, X. et al. Triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio: a surrogate to predict insulin resistance and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol particle size in nondiabetic patients with schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 72, 806–812 (2011).

De Hert, M. et al. Treatment with rosuvastatin for severe dyslipidemia in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 67, 1889–1896 (2006).

Hanssens, L. et al. Pharmacological treatment of severe dyslipidaemia in patients with schizophrenia. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 22, 43–49 (2007).

Perrin, J. M., Friedman, R. A., Knilans, T. K., Black Box Working Group & Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery. Cardiovascular monitoring and stimulant drugs for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 22, 451–453 (2008).

Vetter, V. L. et al. Cardiovascular monitoring of children and adolescents with heart disease receiving medications for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a scientific statement form the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee and the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. Circulation 117, 2407–2423 (2008).

Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and treatment of High Blood Cholesterol (Adult Treatment Part III). JAMA 285, 2486–2497 (2001).

De Hert, M. et al. Guidelines for screening and monitoring of cardiometabolic risk in schizophrenia: systematic evaluation. Brit. J. Psychiatry 199, 99–105 (2011).

Correll, C. U. et al. QT interval duration and dispersion in children and adolescents treated with ziprasidone. J. Clin. Psychiatry 72, 854–860 (2011).

Lehman, A. F. et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am. J. Psychiatry 161 (Suppl. 2), S1–S56 (2004).

Marder, S. R. et al. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 161, 1334–1349 (2004).

European Heart Rhythm Association. et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing committee to develop guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48, e247–e346 (2006).

Maayan, L. & Correll, C. U. Management of antipsychotic-related weight gain. Expert Rev. Neurother. 10, 1175–1200 (2010).

Vreeland, B. Treatment decisions in major mental illness: weighing the outcomes. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68 (Suppl. 12), 5–11 (2007).

Rossi, A. et al. Switching among antipsychotics in everyday clinical practice: focus on ziprasidone. Postgrad. Med. 123, 135–159 (2011).

Hermes, E. et al. The association between weight change and symptom reduction in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr. Res. 128, 166–170 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. De Hert and J. Detraux researched the data for the article and contributed equally to writing the article. R. van Winkel, W. Yu and C. U. Correll made substantial contribution to discussion of content and to reviewing and editing the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M. De Hert declares that he has been a consultant for, received grant and/or research support and honoraria from, and been on the speakers' bureaus and/or advisory boards of the following companies: Astra Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Sanofi Aventis. R. van Winkel declares that he has been a consultant for Eli Lilly and received honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly and Janssen-Cilag. C. U. Correll declares that he has been a consultant and/or advisor for or has received honoraria and/or grants from the following companies: Actelion, AstraZeneca, Biotis, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann-La Roche, IntraCellular Therapies, Lundbeck, Medicure, Merck, Novartis, Otsuka, Ortho-McNeill-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Schering-Plough, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, Vanda. He also has received grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression. J. Detraux and W. Yu declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Hert, M., Detraux, J., van Winkel, R. et al. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat Rev Endocrinol 8, 114–126 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2011.156

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2011.156

This article is cited by

-

Are probiotics effective in reducing the metabolic side effects of psychiatric medication? A scoping review of evidence from clinical studies

Translational Psychiatry (2024)

-

Sex differences in autonomic adverse effects related to antipsychotic treatment and associated hormone profiles

Schizophrenia (2024)

-

Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Schizophrenic Patients Treated with Paliperidone Palmitate Once-Monthly Injection (PP1M): A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study in Taiwan

Clinical Drug Investigation (2024)

-

Evaluating Monitoring Guidelines of Clozapine-Induced Adverse Effects: a Systematic Review

CNS Drugs (2024)

-

Relationship between efficacy and common metabolic parameters in first-treatment drug-naïve patients with early non-response schizophrenia: a retrospective study

Annals of General Psychiatry (2023)