Abstract

Deficits in the generation of auditory mismatch negativity (MMN) generation are among the most widely replicated neurophysiological abnormalities in schizophrenia and are linked to underlying dysfunction of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)-mediated neurotransmission. Here, we evaluate physiological properties of rodent MMN, along with sensitivity to NMDAR agonist and antagonist treatments, relative to known patterns of dysfunction in schizophrenia. Epidural neurophysiological responses to frequency and duration deviants, along with responses to standard stimuli, were obtained at baseline and following 2 and 4 weeks’ treatment in rats treated with saline, phencyclidine (PCP, 15 mg/kg/d by osmotic minipump), or PCP+glycine (16% by weight diet) interventions. Responses were analyzed using both event-related potential (ERP) and neuro-oscillatory (evoked power) approaches. At baseline, rodent duration MMN was associated with increased theta (θ)-frequency response similar to that observed in humans. PCP significantly reduced rodent duration MMN (p<0.001) and θ-band (p<0.01) response. PCP effects were prevented by concurrent glycine treatment (p<0.01 vs PCP alone). Effects related to stimulus-specific adaptation (SSA) were observed primarily in the alpha (α) and beta (β) frequency ranges. PCP treatment also significantly reduced α-frequency response to standard stimuli while increasing θ-band response, reproducing the pattern of deficit observed in schizophrenia. Overall, we demonstrate that rodent duration MMN shows neuro-oscillatory signature similar to human MMN, along with sensitivity to the NMDAR antagonist and agonist administration. These findings reinforce recent human studies linking MMN deficits to θ-band neuro-oscillatory dysfunction and support utility of rodent duration MMN as a translational biomarker for investigation of mechanisms underlying impaired local circuit function in schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a major mental disorder associated with deficits in neurophysiological function that represent a core feature of the disorder. Traditional models of schizophrenia focus on disturbances in dopaminergic function, particularly at D2-type dopamine receptors. By contrast, more recent models focus on disturbances in neurotransmission mediated at N-methyl-D-aspartate-type glutamate receptors (NMDAR). NMDAR models are supported by the ability of NMDAR antagonists such as phencyclidine (PCP) or ketamine to induce symptoms closely resembling those of schizophrenia (Javitt, 2015a; Kantrowitz and Javitt, 2012). Nevertheless, to date, relatively few animal models are available that capture the neurophysiological consequences of NMDAR dysfunction. The present study evaluates mismatch negativity (MMN) as a potential translatable biomarker for etiological investigation of schizophrenia and NMDAR-based new treatment development.

MMN is elicited most commonly in an auditory ‘oddball’ paradigm in which a sequence of repetitive auditory stimuli (‘standards’) is interrupted infrequently by physically deviant ‘oddballs’. Deficits in MMN generation in schizophrenia were first reported over ~20 years ago (Javitt et al, 1993; Shelley et al, 1991) and have been extensively replicated since then (rev. in Javitt and Sweet, 2015). Moreover, MMN deficits correlate highly with functional status in both established (Friedman et al, 2012; Thomas et al, 2017) and prodromal (Bodatsch et al, 2015; Carrion et al, 2015; Perez et al, 2014) schizophrenia, and persist despite treatment with either typical or atypical antipsychotics (Light et al, 2015; Rissling et al, 2012; Umbricht and Krljes, 2005).

At the physiological level, MMN is thought to reflect current flow through open, unblocked NMDAR channels located on supragranular pyramidal neurons within the primary auditory cortex (Javitt et al, 1996; Javitt et al, 1994a). Thus, generation of MMN is reliably blocked in non-human primates by intracortically (Javitt et al, 1996) or systemically (Gil-da-Costa et al, 2013) administered NMDAR antagonists, as well as by subanesthetic doses of ketamine in healthy human volunteers (Rosburg and Kreitschmann-Andermahr, 2016; Umbricht et al, 2000).

Although rodents possess a less complex auditory system than primates, they may nevertheless generate neurophysiological activity analogous to human MMN (Bickel and Javitt, 2009). In particular, rodent MMN activity, like human MMN, survives both ‘flip flop’ and ‘multistandard’ control approaches, and thus appears to represent true deviance-related activity rather than stimulus-specific adaptation (SSA; Chen et al, 2015; Harms et al, 2014; Harms et al, 2016; Jung et al, 2013; Roger et al, 2009). Moreover, as in humans, rodent MMN is inhibited by NMDAR antagonists (Chen et al, 2015; Ehrlichman et al, 2008; Sivarao et al, 2014; Tikhonravov et al, 2008, 2010) suggesting pharmacological homology. To date, studies of NMDAR in rodent MMN generation have utilized only acute manipulations, and have studied only antagonists. Here, we utilize subchronically administered PCP to better reproduce the persistent impairments in NMDAR function that accompany schizophrenia (Javitt et al, 2012) and additionally evaluate sensitivity of MMN to both antagonist (PCP) and agonist (glycine) treatments.

We have previously shown that glycine, administered by dietary supplementation in rodents, produces plasma levels similar to those observed during effective clinical studies with glycine (Heresco-Levy et al, 2004; Heresco-Levy et al, 1999; Javitt et al, 2001; Javitt et al, 1994b), and prevents PCP-induced dopaminergic dysfunction (Javitt et al, 2004). Here, we evaluate the ability of glycine supplementation to prevent PCP-induced neurophysiological impairments during subchronic administration.

Finally, although rodent MMN has mostly been investigated using standard ‘time domain’ event-related potential (ERP) approaches, more recent human studies have utilized ‘time frequency’, neuro-oscillatory approaches in which neurophysiological responses are analyzed as a function of underlying spectral frequency (Javitt et al, 2000; Javitt et al, 2008; Lee et al, 2017). The best studied neuro-oscillatory deficits in schizophrenia occur in the gamma (γ, >24 Hz) frequency band and are thought to reflect downregulation of rapidly firing cortical parvalbumin (PV)-expressing interneurons (Gonzalez-Burgos and Lewis, 2012; Javitt et al, 2008).

By contrast, human MMN occurs primarily in the θ (4–7 Hz) range (Hong et al, 2012; Javitt et al, 2000; Lee et al, 2017), and may depend primarily upon interactions involving more slowly firing somatostatin interneurons (Womelsdorf et al, 2014). In humans, frequency and duration MMNs appear to have different developmental trajectories (Friedman et al, 2012; Todd et al, 2008), and to be differentially dependent upon specific (‘lemniscal’) vs nonspecific (‘non-lemniscal’) thalamic projections to the auditory cortex (Lee et al, 2017). In human studies, we have also recently observed reduced alpha (α, 8–12 Hz) response to standards (Lee et al, 2017). The present study, in addition to being the first to investigate potential NMDAR agonist (glycine) effects on MMN generation in rodents, is also the first to evaluate the time–frequency signature of rodent MMN-like (ie, deviance-related) and N1-like (ie, interstimulus interval (ISI)-related) responses relative to recently described neuro-oscillatory patterns in humans (Lee et al, 2017).

Materials and methods

Surgery and Recording

Sprague–Dawley rats weighing ~300 g were used for stereotaxic implantation of tripolar electrode assemblies (Plastics One, Wallingford, CT). Six electrodes with mounting screws were implanted under chloral hydrate anesthesia to support epidural recording: four at frontal and central midline sites and two above the left and right auditory cortex (Supplementary Figure 1). Following surgery, animals were individually housed and were allowed to recover for at least 7 days before the recording of brain activity.

Neurophysiological Data Acquisition

All ERPs were recorded after 2 h of acclimation in a sound-controlled chamber. Rats were placed in a plastic bowl and connected to a 12-channel commutator (Plastic One) with free access to food. Stimuli were administered free-field using a speaker located above the recording chamber, calibrated to 80 dB. Four separate sessions, involving two recording blocks each separated by 1–2 days, were conducted within each treatment period and averaged to obtain the baseline, 2-week, and 4-week time points. The EEG signal was obtained from epidural electrodes (bone screws) overlying left and right auditory cortex (anterior/posterior −4.30 mm±lateral 3.6 mm from bregma) relative to midline posterior electrode (~1 mm posterior to Lambda) using a Neuroscan SCAN system (Compumedics USA, Charlotte, NC).

In the MMN paradigm, stimuli were presented with fixed 300 ms interval in blocks of 1600 tones. Standard tones (80% sequential probability) were 1000 Hz with 60 ms duration. Duration- (150 ms) and frequency (1500 Hz)-deviant tones were presented with sequential probability of 10% in a pseudorandom order. In the N1 paradigm, repetitive standard tones (1000 Hz, 60 ms, 5 ms rise/fall) were presented with ISI of 1, 3, or 6 s in separate blocks.

Neurophysiological signals were impedance-matched with unity gain pre-amplifiers located near the electrode, and further differentially amplified with bandpass of 0.3 Hz to 3 kHz. Data were acquired continuously along with digital stimulus identification tags at a digitization rate of 10 kHz. Epoching, sorting, artifact rejection, and averaging are then conducted at off-line. Primary analyses focused on neurophysiological responses recorded from bone screws over the left and right auditory cortex.

For both MMN and N1, analysis epochs were 0– 300 ms, relative to a 300-ms prestimulus baseline. Accepted trials were not different among treatment groups with the mean number of sweeps included in the averages as follows: standard: 10 600±936; duration deviant: 1323±117; frequency deviant: 1324±116; 1 s ISI 1: 1847±422; 3 s ISI: 1691±209; 6 s ISI: 1654±182. MMN peaks (80–130 ms window) were derived from deviant-minus-standard difference waveforms. N1 peaks were analyzed with a 70– 120 ms window. No significant treatment effects were observed for latencies of either MMN or N1.

Evoked power (‘power of the average’) time–frequency decomposition was performed using a multitaper method (Hanning window) implemented in Fieldtrip Open toolbox (Oostenveld et al, 2011) with 10 ms time resolution and 1 Hz step of frequency resolution. Integration windows for bands of interest were δ: 3 Hz, 0–300 ms; θ: 6 Hz, 0–220 ms; α: 10 Hz, 50–150 ms; β: 20 Hz, 0–100 ms; γ (early): 34 Hz, 40–70 ms; γ (late): 38 Hz, 80–120 ms.

Drug Administration

Following baseline recordings, rats (n=21) were randomly divided into three groups: control, PCP alone, and PCP+glycine. As in prior studies (Javitt et al, 2004), either saline (vehicle control) or PCP (obtained from NIDA) was administered by Alzet 2ML4 (Alza Corporation) osmotic minipumps implanted under the skin under 3% isoflurane (Henry Schein) anesthesia in a separate surgery from the original electrode implantation. The pumps were filled based on the animal weight at the start of the experiment to deliver 15 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks in both the PCP and PCP+glycine groups. This dose produces sustained plasma PCP levels (~70 ng/ml) that are known to be associated with psychotomimetic effects in humans (Javitt et al, 2004).

Animals assigned to PCP+glycine received a 16% by weight glycine diet (Dyets, Bethlehem, PA) in parallel with PCP. This diet produces plasma levels >1000 μM corresponding to those observed during effective clinical trials with glycine in schizophrenia (Javitt et al, 2004). All other animals received standard laboratory diet.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline analyses across stimulus type were performed using one-way analysis of variance. Longitudinal treatment effects were assessed using linear mixed model regression (MMRM) testing. Post hoc Sidak tests were used to control for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics v. 23 with a preset alpha level for significance of p<0.05 (two-tailed). In initial analyses, no laterality effects were observed for either MMN or N1 measures. Data were therefore averaged across left and right hemispheres.

Results

An initial set of analyses characterized the rodent neurophysiological response at baseline (pre-treatment) using both ERP (‘time domain’) and evoked power, ‘time frequency domain’ neuro-oscillatory approaches (Figure 1). Subsequent analyses characterized the effects of subchronic PCP and PCP+glycine on responses to deviant (Figure 2) and standard (Figure 3) stimuli. A final set of analyses (Figure 4) assessed neuro-oscillatory patterns associated with the rodent analog of the human N1 response, both before and during PCP and PCP+glycine administration.

Mismatch negativity (MMN) responses under baseline (pretreatment) conditions. (a) Event-related potential (ERP) responses to duration- (green shaded region) and frequency-deviant stimuli (blue shaded region) vs standards, and deviant minus standard difference waves. (b) Evoked power (‘frequency domain’) analyses showing responses to standard and deviant stimuli and difference waves. Right: evoked power by frequency. (c) Mean±SEM values by indicated frequency band. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 by paired t-test.

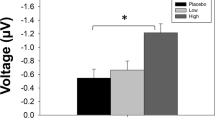

Duration mismatch negativity (MMN) before and during treatment with vehicle alone (Control), phencyclidine (PCP, 15 mg/kg/d by minipump), or PCP+glycine (PCP/gly), administered as 16% by weight diet. (a) Difference waves before and during treatment with indicated agents. MMN was defined as the peak negative amplitude within the shaded region. (b) Mean amplitude across groups. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 by post hoc Sidak. (c) Evoked power plots before and during treatment, and change during vs pretreatment. Open arrows show changes in θ-band response. Closed arrows show changes in late γ-band response. (d) Mean±SEM change by treatment and frequency band. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 by post hoc Sidak test between groups.

Response to standard stimulus during the mismatch negativity (MMN) paradigm before and during treatment with vehicle alone (Control), phencyclidine (PCP, 15 mg/kg/d by minipump), or PCP+glycine administered as 16% by weight diet. (a) Event-related potential (ERP) waves to standard stimuli before and during treatment with indicated agents. (b) The mean amplitude across groups. (c) Evoked power plots before and during treatment, and change during vs pretreatment. Open arrows show changes in α-band response. (d) The mean change by treatment and frequency band. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 by post hoc Sidak test between groups.

Response to repetitive standard stimuli as a function of interstimulus interval (ISI, N1 experiment). (a) Event-related potential (ERP) waves as a function of ISI. (b) Mean±SEM amplitude by ISI. (c) Evoked power plots by ISI. (d) Mean±SEM amplitude by frequency band and ISI. **denotes time interval of significant ISI effect.

Mismatch Negativity

Baseline MMN

At baseline, standard stimuli elicited a negative deflection over the bilateral auditory cortex, relative to a posterior midline reference (Figure 1a). In ERP, duration-deviant stimuli elicited a significantly enhanced response relative to standards (t20=5.89, p<0.0001, d=1.90). By contrast, the responses to frequency deviants did not differ significantly from the response to standards alone (t20=1.53, p=0.14, d=0.68).

In evoked power analyses, activity elicited in response to the standard stimuli was confined primarily to the β-frequency band during the 0–50 ms latency range, with small additional γ-band response and δ-power centered at the 3.3 Hz (300 ms ISI) overall stimulation rate (Figure 1b). Both θ- (F2,19=19.2, p<0.0001) and δ- (F2,19=11.4, p<0.01) band activities were significantly modulated by stimulus type. In the case of θ-band activity, evoked amplitude was markedly larger to duration deviants than either frequency deviants (F1,20=19.92, p<0.0001) or standards (F1,20=31.5, p<0.0001), although θ-frequency responses were larger to frequency deviants than to standards as well. In the case of δ-band activity, both duration (F1,20=10.5, p<0.01) and frequency (F1,20=13.3, p<0.01) deviants elicited greater response than standards.

By contrast, β-band activity, although modulated by stimulus type (F2,19=10.3, p<0.01), only differed significantly in response to frequency deviants vs standards (F1,20=21.7, p<0.0001), whereas β-band response to duration deviants vs standards was nonsignificant (F1,20=2.0, p=0.17). Both γ- (F2,19=7.2, p<0.01) and α- (F2,19=35.2, p<0.0001) band activity also differed significantly across stimulus type, with larger values for deviant vs standard stimuli (Figure 1). Differences in θ-band response to duration deviants vs standards remained significant even following control for the difference in β-response (F1,20=43.8, p<0.0001).

In the ERP waves, a small off-response was seen to the duration-deviant stimulus, peaking at ~250 ms, but was without a prominent neuro-oscillatory correlate.

Treatment effects

A second set of analyses (Figure 2) evaluated the effect of PCP alone and combined PCP+glycine treatment on duration and frequency MMN activity across the 2- and 4-week assessment periods, relative to baseline. An initial evaluation of the data showed no significant difference in response at 2 vs 4 weeks for ERP (duration MMN: F1,36=0.11, p=0.74; frequency MMN: F1,36=1.17, p=0.29). Post-treatment data were therefore collapsed across these two time points to assess treatment effects.

For duration-deviant stimuli, the overall MMN waveform morphology and latency remained similar pre- vs post treatment (Figure 2a). An MMRM analysis focusing on change in MMN amplitude with treatment showed a significant main effect of treatment type (F2,36=9.03, p<0.001), reflecting reduced MMN generation during treatment in the PCP alone group (F1,14=5.24, p<0.05), but not in either the control (F1,12=1.3, p=0.31) or combined PCP+glycine (F1,10=0.01, p=0.97) groups. Differences between the control and PCP-alone groups (Sidak p<0.01) and between PCP-alone and PCP+glycine groups (Sidak p<0.05) were statistically reliable (Figure 2b and Supplementary Table 1).

Evoked power

When similar analyses were conducted in the time–frequency domain (Figure 2c), significant variations were observed for θ-band activity across treatment groups (F2,36=5.15, p<0.01), with significant reduction during treatment in the PCP group vs control (Sidak p<0.05) and significant prevention of the effect by concurrent glycine treatment (Sidak p<0.05 PCP+glycine vs PCP alone; Figure 2d, open arrow). PCP treatment also led to a significant increase in δ-band activity (F2,36=4.62, p<0.05; PCP group vs control: Sidak p<0.05). No corresponding change occurred in the combined PCP+glycine group, although the difference vs PCP alone was nonsignificant (Sidak p=0.31).

The initial γ-band response (0–50 ms) was not significantly affected by either PCP or combined PCP+glycine treatment (F2,36=2.21, p=0.12). However, a significant reduction in late (~100 ms) activity was observed in the PCP-alone group across the β/γ-frequency bands (Figure 2c, closed arrow). This reduction was prevented by simultaneous glycine treatment, as reflected in a significant reduction in the late γ-band in the PCP group vs both the control (Sidak p<0.001) and combined PCP+glycine (Sidak p<0.001) groups.

By contrast to duration-induced ERP and neuro-oscillatory effects, no significant effects were observed on responses to frequency-deviant stimuli by either PCP or combined PCP+glycine treatment (Supplementary Table 1).

Response to Standards

ERP

In ERP analyses, the most prominent response was an N1-like negative deflection peaking at ~100 ms. As opposed to deviance-related activity, no significant change occurred over time to the N1 response to standards in any treatment group, nor were significant between-group effects observed when analyses were restricted to time-domain (ERP) analyses (Figures 3a and b).

Evoked power

In neuro-oscillatory analyses, the response to standards occurred primarily in the β- and α-bands, with smaller activity in the δ- and θ-bands. No significant PCP effect was observed on initial β-activity. By contrast, both α- (F2,36=14.02, p<0.0001) and θ- (F2,36=4.90, p<0.05) activities were significantly affected by treatment type. Specifically during treatment, a significant reduction in α-band activity was observed in the PCP group (F2,36=14.02, p<0.0001), leading to a significant difference in change score vs controls (Sidak p<0.01). This reduction was prevented by concurrent glycine treatment (Sidak p<0.01 vs PCP alone; Figure 3c and Supplementary Table 2).

By contrast to its effect on α-band activity, PCP treatment significantly increased θ-band activity (F2,36=4.90, p<0.05), leading to significant differences vs both control (Sidak p<0.05) and combined PCP+glycine (Sidak p<0.05) treatment.

As with deviants, late γ-band activity was also modulated by treatment (F2,36=6.74, p<0.01), with reductions in the PCP group relative to both control and combined PCP+glycine treatments (Sidak p<0.01 for both). As with deviants, β-activity was increased during PCP+glycine treatment levels over levels observed in either controls (Sidak p<0.05) or PCP conditions (Sidak p<0.05).

Refractoriness Function

In order to address relative effects of SSA vs deviance, ERP to repetitive standards were also evaluated as a function of ISI both at baseline and during treatment. As expected, the amplitude of the N1 response increased significantly as ISI increased from 300 ms to 6 s (F3,18=25.53, p<0.0001; Figure 4). As opposed to MMN, where the greatest difference between deviants and standards was observed in θ, ISI effects were observed primarily as an enhancement of β (F3,18=27.2, p<0.0001) and α- (F3,18=11.72, p<0.001) band response (Figure 4). A smaller, but significant, increase in δ-band response was observed as well (F3,18=12.0, p<0.001). Although θ-band activity increased along with β- and α-band activity (F3,18=12.2, p<0.001), there was no clear peak in the θ-band, and the change in θ-response was no longer significant following covariation for changes in β- (F3,18=0.67, p=0.6) activity.

As with MMN, N1 amplitude was significantly modulated by treatment type (F2,108=18.57, p<0.0001), with significant differences between PCP and control conditions (Sidak p<0.001) and combined PCP+glycine vs PCP alone (Sidak p<0.05) across levels of ISI. Nevertheless, N1 remained significantly reduced in combined PCP+glycine vs control treatment (p<0.05; Supplementary Figure 2).

In neuro-oscillatory analyses, significant PCP-induced reductions were observed primarily in the β-frequency band (F2,108=30.0, p<0.0001), with reduced β-amplitude across ISIs in the PCP group vs controls (Sidak p<0.001). The group × ISI effect was significant as well (F4,108=2.54, p<0.05), reflecting somewhat greater effect at long vs short ISI. Simultaneous glycine treatment led to a significant (Sidak p<0.01) but partial prevention of the effect, which was independently significant at the 3- s ISI only (p<0.05; Supplementary Table 3).

Effects on baseline amplitude

Effects on ongoing EEG amplitude were assessed during the pre-stimulus interval in the long ISI conditions. Neither PCP nor PCP+glycine treatment affected baseline activity in the δ-, θ-, or γbands (all p>0.1). Significant effects of PCP+glycine treatment were observed on β- (F2,108=7.76, p<0.01) and α- (F2,108=5.99, p<0.01) band activities vs control (Supplementary Table 4).

Control analysis

Because of potential concerns, a control study was performed in a set of naive rats to insure that differential θ-generation to deviants vs standards was not due to the differential physical properties of the stimuli (ie, 150 vs 60 ms duration). Six experiments were conducted across three rats (Supplementary Table 5), in which 150 ms duration stimuli were presented both as deviants vs 60 ms standards, and as standards in a separate run.

As expected, significant but small differences were observed in the sensory responses to the two stimuli, reflecting potentially the differential timing of the off-responses, as well as a potential small sustained potential (SP; Figure 5a). When the response to the 150 ms (Figure 5b) and 60 ms (Figure 5c) standards was evaluated in the time–frequency domain, the differential power mapped primarily to the α- and β-frequency ranges (Figure 5d), with no significant difference in θ-power difference during the MMN interval (p=0.21; Supplementary Table 5). Our finding of limited stimulus duration-related effects relative to MMN effects is consistent with prior duration MMN literature (eg, Jaramillo et al, 2000), and suggests that a similar relationship holds for rodent MMN as well.

Results of a control analysis evaluating the sensory response to 150 vs 60 ms standards (Std) and the potential relationship to mismatch negativity (MMN). For these experiments, complementary runs were collected with 150 ms deviants presented vs 60 ms standards in one run (10% sequential probability), and 60 ms deviants presented against 150 ms standards in a separate run. Comparisons were conducted both within and across runs. (a) Differential time-domain response, showing a longer sustained potential (SP) to the 150 vs 60 ms std. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 for sequential significance (Guthrie and Buchwald, 1991). (b) Time–frequency plot of response to 150 ms standard stimulus, showing primary activity in the β- and α-frequency ranges. (c) Time–frequency plot of response to 60 ms standard, showing predominant activity in the β-range (compare to Figure 1b). (d) Difference (Diff) in time–frequency response to 150 vs 60 ms standards reflecting the SP. Note predominant differential activity in the β and α with limited differential activity in the θ-frequency band. (e) Differential time-domain response showing a significantly larger response to the 150 ms deviant vs standard in the 80–120 ms latency range. (f) Time–frequency response to 150 ms duration stimuli presented as deviants against 60 ms standards. (g) Diff in time–frequency response to 150 ms deviants minus 150 ms standards, showing prominent difference in the θ-frequency band. No different scales for responses to standard and deviant stimuli (b, c, f) vs difference panels (d, g).

In this updated data set, a significant MMN was observed to 150 ms duration deviants (vs 60 ms standards) even when the deviants’ response was compared with the 150 ms standard stimulus from a separate run (‘like from like’ comparison), with significantly different peak amplitudes during the 80–120 ms latency range (−13.1±7.9 vs −4.1±2.3 μV, t=2.65, df=12, p=0.02). A sustained difference was also observed throughout the 80–120 ms interval (Figure 5e). In time–frequency analyses, the θ-power difference between the 150 ms deviants and 60 ms standards within the MMN run was significant even within this limited sample size (p=0.003; Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

Although MMN deficits in schizophrenia have been replicated extensively, use of MMN in etiological investigations and translational treatment development programs remains severely limited. Results of the present study are threefold.

First, we provide the first demonstration that in rodents, as in our recent clinical study (Lee et al, 2017), the brain response to deviant, MMN-eliciting stimuli is differentiated from the response to repetitive standards based upon neuro-oscillatory characteristics. This finding not only helps resolve specific scientific issues regarding the degree to which rodent MMN is an appropriate analog of human MMN, but also the degree to which MMN in general reflects stimulus-specific adaptation vs de novo activity elicited by deviant stimuli against a backdrop of prior standards (ie, deviance-related activity). In addition, it links MMN dysfunction to emerging literature regarding somatostatin interneuron, along with PV interneuron, dysfunction in schizophrenia (Hamm and Yuste, 2016; Smiley et al, 2000; Volk et al, 2016).

Second, we provide the first demonstration that rodent MMN is reduced during subchronic treatment with the NMDAR antagonist PCP. This amplifies findings from prior acute studies in rodents (Chen et al, 2015; Ehrlichman et al, 2008; Sivarao et al, 2014; Tikhonravov et al, 2008, 2010), primates (Gil-da-Costa et al, 2013; Javitt et al, 1996), and humans (Rosburg and Kreitschmann-Andermahr, 2016; Umbricht et al, 2000), and provides a platform to assess the effects of subchronic treatment with putative NMDAR agonists.

Third, we provide the first demonstration that subchronic administration of the NMDAR agonist glycine, at doses relevant to its clinical effects (Heresco-Levy et al, 2004; Heresco-Levy et al, 1999; Javitt et al, 2004; Javitt et al, 2001; Javitt et al, 1994b), significantly prevents PCP-induced abnormalities in response to both the standard and deviant stimuli.

Deviance-Related Activity vs SSA

MMN was first demonstrated in the late 1970s using an auditory oddball paradigm (Naatanen et al, 1978), and its reduction in schizophrenia was first demonstrated in the early 1990s (Javitt et al, 1993; Shelley et al, 1991). Despite the well-replicated nature of both the MMN phenomenon and its deficits in schizophrenia, the degree to which MMN reflects de novo activity generated by deviants (often termed ‘prediction error’, Friston, 2005)) vs SSA of the sensory N1 potential remains a topic of ongoing discussion (eg, Harms et al, 2016)).

Here, we demonstrate that in rodents MMN responses to deviants differ in spectral content from N1 responses to standards, suggesting different underlying generator mechanisms. These findings also support our recent clinical study showing primarily a θ-frequency response to deviants vs a mixed α-/θ-frequency response to standards. Consistent with present PCP results, both deviant- and standard-related activities were significantly reduced in schizophrenia (Lee et al, 2017), suggested dysfunction of both corticocortical and thalamocortical circuits (Haegens et al, 2015; Potes et al, 2014).

In humans, as in the present study, in addition to evoking α-frequency responses, repetitive standard stimuli actively suppress θ-band activity. In schizophrenia patients, as in PCP-treated rats, θ-band elicited by standard stimuli was significantly increased even while α-band response was decreased. As with PCP-induced decreases in θ-band to duration-deviant stimuli (Figure 2), θ-band increases to standard stimuli were prevented by concurrent glycine treatment (Figure 1), suggesting that NMDAR dysfunction may contribute to both sets of dysfunction in schizophrenia.

PCP Effects on MMN and N1 Activity

A second finding is that subchronic administration of the NMDAR antagonist PCP led to a persistent reduction in both MMN generation and in N1 refractoriness functions during the administration period. Prior studies in rodents, primates, and humans have extensively documented the effects of acute NMDAR antagonists (Umbricht et al, 2000), but subchronic effects have been less well studied.

Here, we treated rodents for 4 weeks using an administration routine that produces PCP blood levels highly similar to those observed during PCP-induced psychosis in humans (~70 ng/ml; Balla et al, 2003). As with acute treatment, subchronic PCP significantly reduced MMN generation. No significant differences in the response pattern were observed at 2 vs 4 weeks, suggesting that 2-week treatment is sufficient to obtain a stable reduction in MMN and N1 response.

Although the primary focus of this study was on MMN response, we also evaluated effects of PCP on response to repetitive standards. Similar to its effects on MMN, PCP reduced the ISI-related increase in rodent N1 amplitude, with most prominent effects in the β- and α-frequency bands.

Glycine Effects

Third, we evaluated the ability of glycine to prevent PCP-induced MMN abnormalities. In clinical studies, glycine induces significant improvement in persistent negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia when used clinically at doses (eg, >60 g/d) that result in plasma levels in excess of 1000 μM (Heresco-Levy et al, 2004; Heresco-Levy et al, 1999; Javitt et al, 2001). By contrast, studies with lower achieved glycine levels (eg, 500 μM, Buchanan et al, 2007) have generally not observed significant effects.

The dose of glycine used for this study (16% by weight diet) produces sustained glycine levels in rodents in excess of 1000 μM, along with an ~2 × increase in brain glycine levels (Javitt et al, 2004). We have previously shown that this dose significantly prevents PCP-induced dopaminergic hyper-reactivity, consistent with its beneficial clinical effects (Javitt et al, 2004). Here, as predicted, concurrent glycine significantly prevented the PCP-induced reductions in MMN generation both in time (ERP; Figure 1) and time–frequency (neuro-oscillatory) domain (Figure 2) analyses, suggesting that both sets of measures may serve as effective translational measures.

We also observed that PCP treatment did not modulate the initial (0–50 ms) γ-band response induced by either standard or deviant stimuli, but did significantly reduce later-stage activity in the 50–150 ms latency range. This effect, like the effect on concurrent θ-activity, was significantly prevented by concurrent glycine treatment. γ-band deficits have been extensively reported in schizophrenia to rapidly presented (eg, 40 Hz) stimuli (rev. in McNally and McCarley, 2016). However, consistent with results of the present study, γ-band responses to stimuli presented at lower stimulation frequencies (eg, 3 Hz, as in the present study) may be intact. Deficits in γ-generation in schizophrenia, in general, are thought to represent long-term adaptation to NMDAR blockade, mediated through downregulation of GAD67 and PV levels, rather than NMDAR dysfunction itself (Jadi et al, 2016; Rotaru et al, 2012). Nevertheless, the present study suggests a late phase of γ-band activity that may be NMDAR-sensitive, and may represent an additional target for new treatment development (Javitt et al, 2008; Light et al, 2017).

Limitations

A limitation of the present study is that no control conditions were incorporated to demonstrate that the additional response to duration deviants reflected specifically deviance-related activity (ie, ‘true’ MMN) rather than differential sensory-driven activity elicited by the longer duration-deviant stimulus. Nevertheless, this issue has been extensively evaluated in prior literature. The initial demonstration of MMN to duration-deviant stimuli in awake, freely moving rats was shown by Roger et al (2009), who used a shorter-duration deviant to elicit the MMN.

Subsequently, Nakamura et al (2011) replicated these findings using both ‘flip-flop’ and ‘multistandard’ control conditions using 50 and 150 ms stimuli. Similar to the present study, these authors observed a late-difference wave to long-duration deviants during the 100–160 ms latency range that was significant relative to both a short- or long-duration standard, using comprehensive criteria for differentiation of SSA- from deviance-related activity (Harms et al, 2016).

The use of neuro-oscillatory analysis further differentiates deviance- from standard-related activity. In humans, neuro-oscillatory responses to standards occur in the α-/θ-frequency ranges and thus partially overlap the deviance-related response, which occurs primarily within the θ-frequency range (Lakatos et al, 2013; Lee et al, 2017). By contrast, in the present study standard-induced activity occurred primarily in the β-frequency range (Figure 1b, left-most panel), with limited θ-activity even at long ISI (eg, >3 s, Figure 4c), potentially consistent with the shorter thalamocortical projections in rodents vs humans.

By contrast, deviance-related activity remained in the θ-frequency range, similar to that observed in humans. The differential spectral profile in response to deviant vs standard stimuli in rodents thus further supports the involvement of differential cortical circuits in the generation of N1-like vs MMN-like activity (further discussed in Javitt (2015b)), and further argues against SSA as a basis for the present deviance-related findings.

Notably, PCP treatment increased θ-responses to standards even while decreasing θ-responses to deviants, similar to the impairment pattern observed in schizophrenia (Lee et al, 2017). Both sets of effects were prevented by concurrent glycine treatment. In a control analysis, we evaluated the degree to which the differential θ-activity to longer-duration deviants vs shorter standards might reflect a SP, rather than a true MMN. However, no significant differential θ-activity was observed in 150 vs 60 ms standards (Figure 5d), while large differential θ-activity was observed to the 150 ms deviant vs the 150 ms standard (Figure 5g), arguing against this possibility, consistent with prior human studies (Jaramillo et al, 2000).

A second limitation of the present study is that tones were presented at the lower end of the hearing range, and thus may not have been ideal for eliciting frequency MMN (Harms et al, 2016). Other studies with rodents have observed MMN-like activity to frequency, as well as duration, deviants (rev. in Harms et al, 2016). To the extent that differences in generation of duration- vs frequency MMN is observed in rodents, differential engagement of lemniscal vs non-lemniscal components of the subcortical auditory system (Lee et al, 2017), as well as different neurodevelopmental characteristics of the duration- vs frequency MMN generators (Friedman et al, 2012; Todd et al, 2008).

Consistent with the present results, several studies have shown inhibition of late deviance-related (ie, MMN) activity in rodents by acute administration of NMDAR antagonists (Harms et al, 2017; Sivarao et al, 2014; Tikhonravov et al, 2008). Here we provide the first evidence that such deficits are maintained during subchronic (2–4 week) treatment, providing a platform to assess effects of subchronically administered medication (Nakamura et al, 2011).

The use of 16% (by weight) diet is also different from the usual method for giving glycine in humans (oral supplementation). Nevertheless, this approach produces glycine levels very similar to those observed in human clinical trials (Javitt et al, 2004) and is easy to administer and well-tolerated in rodents. In prior studies, we have shown that subchronic PCP treatment produces increased behavioral and in vivo dopaminergic response to amphetamine, similar to that observed in schizophrenia, and that such effects are reversed by 16% glycine diet (Javitt et al, 2004), supporting relevance of this model to schizophrenia.

Summary

Overall, our findings strongly support rodent duration MMN as an appropriate translational model for NMDAR-based treatment development. The neurophysiological homology between rodent and human MMN, moreover, suggests that rodent neuro-oscillatory models may be useful for exploring mechanisms underlying impaired MMN generation in schizophrenia.

Funding and disclosure

This study was funded by NIMH grants P50 MH086385 and R01 MH49334 to DCJ. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Balla A, Sershen H, Serra M, Koneru R, Javitt DC (2003). Subchronic continuous phencyclidine administration potentiates amphetamine-induced frontal cortex dopamine release. Neuropsychopharmacology 28: 34–44.

Bickel S, Javitt DC (2009). Neurophysiological and neurochemical animal models of schizophrenia: focus on glutamate. Behav Brain Res 204: 352–362.

Bodatsch M, Brockhaus-Dumke A, Klosterkotter J, Ruhrmann S (2015). Forecasting psychosis by event-related potentials-systematic review and specific meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry 77: 951–958.

Buchanan RW, Javitt DC, Marder SR, Schooler NR, Gold JM, McMahon RP et al (2007). The Cognitive and Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia Trial (CONSIST): the efficacy of glutamatergic agents for negative symptoms and cognitive impairments. Am J Psychiatry 164: 1593–1602.

Carrion RE, Cornblatt BA, McLaughlin D, Chang J, Auther AM, Olsen RH et al (2015). Contributions of early cortical processing and reading ability to functional status in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res 164: 1–7.

Chen IW, Helmchen F, Lutcke H (2015). Specific early and late oddball-evoked responses in excitatory and inhibitory neurons of mouse auditory cortex. J Neurosci 35: 12560–12573.

Ehrlichman RS, Maxwell CR, Majumdar S, Siegel SJ (2008). Deviance-elicited changes in event-related potentials are attenuated by ketamine in mice. J Cogn Neurosci 20: 1403–1414.

Friedman T, Sehatpour P, Dias E, Perrin M, Javitt DC (2012). Differential relationships of mismatch negativity and visual p1 deficits to premorbid characteristics and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 71: 521–529.

Friston K (2005). A theory of cortical responses. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 360: 815–836.

Gil-da-Costa R, Stoner GR, Fung R, Albright TD (2013). Nonhuman primate model of schizophrenia using a noninvasive EEG method. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 15425–15430.

Gonzalez-Burgos G, Lewis DA (2012). NMDA receptor hypofunction, parvalbumin-positive neurons, and cortical gamma oscillations in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 38: 950–957.

Guthrie D, Buchwald JS (1991). Significance testing of difference potentials. Psychophysiology 28: 240–244.

Haegens S, Barczak A, Musacchia G, Lipton ML, Mehta AD, Lakatos P et al (2015). Laminar profile and physiology of the alpha rhythm in primary visual, auditory, and somatosensory regions of neocortex. J Neurosci 35: 14341–14352.

Hamm JP, Yuste R (2016). Somatostatin interneurons control a key component of mismatch negativity in mouse visual cortex. Cell Rep 16: 597–604.

Harms L, Fulham WR, Todd J, Budd TW, Hunter M, Meehan C et al (2014). Mismatch negativity (MMN) in freely-moving rats with several experimental controls. PLoS ONE 9: e110892.

Harms L, Fulham WR, Todd J, Meehan C, Schall U, Hodgson DM et al (2017). Late deviance detection in rats is reduced, while early deviance detection is augmented by the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801. Schizophr Res (in press).

Harms L, Michie PT, Naatanen R (2016). Criteria for determining whether mismatch responses exist in animal models: focus on rodents. Biol Psychol 116: 28–35.

Heresco-Levy U, Ermilov M, Lichtenberg P, Bar G, Javitt DC (2004). High-dose glycine added to olanzapine and risperidone for the treatment of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 55: 165–171.

Heresco-Levy U, Javitt DC, Ermilov M, Mordel C, Silipo G, Lichtenstein M (1999). Efficacy of high-dose glycine in the treatment of enduring negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56: 29–36.

Hong LE, Moran LV, Du X, O'Donnell P, Summerfelt A (2012). Mismatch negativity and low frequency oscillations in schizophrenia families. Clin Neurophysiol 123: 1980–1988.

Jadi MP, Behrens MM, Sejnowski TJ (2016). Abnormal gamma oscillations in n-methyl-D-aspartate receptor hypofunction models of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 79: 716–726.

Jaramillo M, Paavilainen P, Naatanen R (2000). Mismatch negativity and behavioural discrimination in humans as a function of the magnitude of change in sound duration. Neurosci Lett 290: 101–104.

Javitt DC (2015a). Current and emergent treatments for symptoms and neurocognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Curr Treat Opt Psychiatry 1: 107–120.

Javitt DC (2015b). Neurophysiological models for new treatment development in schizophrenia: early sensory approaches. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1344: 92–104.

Javitt DC, Balla A, Burch S, Suckow R, Xie S, Sershen H (2004). Reversal of phencyclidine-induced dopaminergic dysregulation by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor/glycine-site agonists. Neuropsychopharmacology 29: 300–307.

Javitt DC, Doneshka P, Zylberman I, Ritter W, Vaughan HG Jr (1993). Impairment of early cortical processing in schizophrenia: an event-related potential confirmation study. Biol Psychiatry 33: 513–519.

Javitt DC, Shelley A, Ritter W (2000). Associated deficits in mismatch negativity generation and tone matching in schizophrenia. Clin Neurophysiol 111: 1733–1737.

Javitt DC, Silipo G, Cienfuegos A, Shelley AM, Bark N, Park M et al (2001). Adjunctive high-dose glycine in the treatment of schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 4: 385–391.

Javitt DC, Spencer KM, Thaker GK, Winterer G, Hajos M (2008). Neurophysiological biomarkers for drug development in schizophrenia. Nat Rev 7: 68–83.

Javitt DC, Steinschneider M, Schroeder CE, Arezzo JC (1996). Role of cortical N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in auditory sensory memory and mismatch negativity generation: implications for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 11962–11967.

Javitt DC, Steinschneider M, Schroeder CE, Vaughan HG Jr, Arezzo JC (1994a). Detection of stimulus deviance within primate primary auditory cortex: intracortical mechanisms of mismatch negativity (MMN) generation. Brain Res 667: 192–200.

Javitt DC, Sweet RA (2015). Auditory dysfunction in schizophrenia: integrating clinical and basic features. Nat Rev Neurosci 16: 535–550.

Javitt DC, Zukin SR, Heresco-Levy U, Umbricht D (2012). Has an angel shown the way? Etiological and therapeutic implications of the PCP/NMDA model of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 38: 958–966.

Javitt DC, Zylberman I, Zukin SR, Heresco-Levy U, Lindenmayer JP (1994b). Amelioration of negative symptoms in schizophrenia by glycine. Am J Psychiatry 151: 1234–1236.

Jung F, Stephan KE, Backes H, Moran R, Gramer M, Kumagai T et al (2013). Mismatch responses in the awake rat: evidence from epidural recordings of auditory cortical fields. PLoS ONE 8: e63203.

Kantrowitz J, Javitt DC (2012). Glutamatergic transmission in schizophrenia: from basic research to clinical practice. Curr Opin Psychiatry 25: 96–102.

Lakatos P, Schroeder CE, Leitman DI, Javitt DC (2013). Predictive suppression of cortical excitability and its deficit in schizophrenia. J Neurosci 33: 11692–11702.

Lee M, Sehatpour P, Hoptman MJ, Lakatos P, Dias EC, Kantrowitz JT et al (2017). Neural mechanisms of mismatch negativity dysfunction in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry (in press).

Light GA, Swerdlow NR, Thomas ML, Calkins ME, Green MF, Greenwood TA et al (2015). Validation of mismatch negativity and P3a for use in multi-site studies of schizophrenia: characterization of demographic, clinical, cognitive, and functional correlates in COGS-2. Schizophr Res 163: 63–72.

Light GA, Zhang W, Joshi YB, Bhakta S, Talledo JA, Swerdlow NR (2017). Single-dose memantine improves cortical oscillatory response dynamics in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology (in press).

McNally JM, McCarley RW (2016). Gamma band oscillations: a key to understanding schizophrenia symptoms and neural circuit abnormalities. Curr Opin Psychiatry 29: 202–210.

Naatanen R, Gaillard AW, Mantysalo S (1978). Early selective-attention effect on evoked potential reinterpreted. Acta Psychol 42: 313–329.

Nakamura T, Michie PT, Fulham WR, Todd J, Budd TW, Schall U et al (2011). Epidural auditory event-related potentials in the rat to frequency and duration deviants: evidence of mismatch negativity? Front Psychol 2: 367.

Oostenveld R, Fries P, Maris E, Schoffelen JM (2011). FieldTrip: open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput Intel Neurosci 2011: 156869.

Perez VB, Woods SW, Roach BJ, Ford JM, McGlashan TH, Srihari VH et al (2014). Automatic auditory processing deficits in schizophrenia and clinical high-risk patients: forecasting psychosis risk with mismatch negativity. Biol Psychiatry 75: 459–469.

Potes C, Brunner P, Gunduz A, Knight RT, Schalk G (2014). Spatial and temporal relationships of electrocorticographic alpha and gamma activity during auditory processing. Neuroimage 97: 188–195.

Rissling AJ, Braff DL, Swerdlow NR, Hellemann G, Rassovsky Y, Sprock J et al (2012). Disentangling early sensory information processing deficits in schizophrenia. Clin Neurophysiol 123: 1942–1949.

Roger C, Hasbroucq T, Rabat A, Vidal F, Burle B (2009). Neurophysics of temporal discrimination in the rat: a mismatch negativity study. Psychophysiology 46: 1028–1032.

Rosburg T, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I (2016). The effects of ketamine on the mismatch negativity (MMN) in humans - a meta-analysis. Clin Neurophysiol 127: 1387–1394.

Rotaru DC, Lewis DA, Gonzalez-Burgos G (2012). The role of glutamatergic inputs onto parvalbumin-positive interneurons: relevance for schizophrenia. Rev Neurosci 23: 97–109.

Shelley AM, Ward PB, Catts SV, Michie PT, Andrews S, McConaghy N (1991). Mismatch negativity: an index of a preattentive processing deficit in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 30: 1059–1062.

Sivarao DV, Chen P, Yang Y, Li YW, Pieschl R, Ahlijanian MK (2014). NR2B antagonist CP-101,606 abolishes pitch-mediated deviance detection in awake rats. Front Psychiatry 5: 96.

Smiley JF, McGinnis JP, Javitt DC (2000). Nitric oxide synthase interneurons in the monkey cerebral cortex are subsets of the somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, and calbindin cells. Brain Res 863: 205–212.

Thomas ML, Green MF, Hellemann G, Sugar CA, Tarasenko M, Calkins ME et al (2017). Modeling deficits from early auditory information processing to psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 74: 37–46.

Tikhonravov D, Neuvonen T, Pertovaara A, Savioja K, Ruusuvirta T, Naatanen R et al (2008). Effects of an NMDA-receptor antagonist MK-801 on an MMN-like response recorded in anesthetized rats. Brain Res 1203: 97–102.

Tikhonravov D, Neuvonen T, Pertovaara A, Savioja K, Ruusuvirta T, Naatanen R et al (2010). Dose-related effects of memantine on a mismatch negativity-like response in anesthetized rats. Neuroscience 167: 1175–1182.

Todd J, Michie PT, Schall U, Karayanidis F, Yabe H, Naatanen R (2008). Deviant matters: duration, frequency, and intensity deviants reveal different patterns of mismatch negativity reduction in early and late schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 63: 58–64.

Umbricht D, Krljes S (2005). Mismatch negativity in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 76: 1–23.

Umbricht D, Schmid L, Koller R, Vollenweider FX, Hell D, Javitt DC (2000). Ketamine-induced deficits in auditory and visual context-dependent processing in healthy volunteers: implications for models of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57: 1139–1147.

Volk DW, Edelson JR, Lewis DA (2016). Altered expression of developmental regulators of parvalbumin and somatostatin neurons in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 177: 3–9.

Womelsdorf T, Valiante TA, Sahin NT, Miller KJ, Tiesinga P (2014). Dynamic circuit motifs underlying rhythmic gain control, gating and integration. Nat Neurosci 17: 1031–1039.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, M., Balla, A., Sershen, H. et al. Rodent Mismatch Negativity/theta Neuro-Oscillatory Response as a Translational Neurophysiological Biomarker for N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor-Based New Treatment Development in Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol. 43, 571–582 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.176

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.176

This article is cited by

-

Neurexin1α knockout rats display oscillatory abnormalities and sensory processing deficits back-translating key endophenotypes of psychiatric disorders

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

Mismatch negativity as EEG biomarker supporting CNS drug development: a transnosographic and translational study

Translational Psychiatry (2021)

-

A roadmap for development of neuro-oscillations as translational biomarkers for treatment development in neuropsychopharmacology

Neuropsychopharmacology (2020)