Abstract

Poor behavioral inhibition is a common feature of neurological and psychiatric disorders. Successful inhibition of a prepotent response in ‘NoGo’ paradigms requires the integrity of both the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and the serotonergic system. We investigated individual differences in serotonergic regulation of response inhibition. In 24 healthy adults, we used 18F-altanserin positron emission tomography to assess cerebral 5-HT2A receptors, which have been related to impulsivity. We then investigated the impact of two acute manipulations of brain serotonin levels on behavioral and neural correlates of inhibition using intravenous citalopram and acute tryptophan depletion during functional magnetic resonance imaging. We adapted the NoGo paradigm to isolate effects on inhibition per se as opposed to other aspects of the NoGo paradigm. Successful NoGo inhibition was associated with greater activation of the right IFG compared to control trials with alternative responses, indicating that the IFG is activated with inhibition in NoGo trials rather than other aspects of invoked cognitive control. Activation of the left IFG during NoGo trials was greater with citalopram than acute tryptophan depletion. Moreover, with the NoGo-type of response inhibition, the right IFG displayed an interaction between the type of serotonergic challenge and neocortical 5-HT2A receptor binding. Specifically, acute tryptophan depletion (ATD) produced a relatively larger NoGo response in the right IFG in subjects with low 5-HT2A BPP but reduced the NoGo response in those with high 5-HT2A BPP. These links between serotonergic function and response inhibition in healthy subjects may help to interpret serotonergic abnormalities underlying impulsivity in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Impaired response inhibition is common in neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. One of the most studied forms of inhibition is restraint of a prepotent response exemplified by ‘NoGo’ tasks (Iversen and Mishkin, 1970; Konishi et al, 1999). Specific anatomical structures are implicated in response inhibition including inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) (Wager et al, 2005; Levy and Wagner, 2011), evidenced by IFG lesions (Aron et al, 2003; Swick et al, 2008), neuroimaging (Konishi et al, 1998; Konishi et al, 1999; Asahi et al, 2004; Del-Ben et al, 2005; Rubia et al, 2005; Chikazoe et al, 2007; Langenecker et al, 2007; Simmonds et al, 2008; Zheng et al, 2008; Chikazoe et al, 2009), and electrophysiology (Swann et al, 2009). Many studies emphasize right IFG, but left IFG is also involved (Rubia et al, 2001; Swick et al, 2008).

Response inhibition also shows neurochemical specificity. NoGo inhibition is strongly associated with integrity of serotonergic system in humans and animals (Eagle et al, 2008). This contrasts with noradrenergic modulation of the stop response required by stop-signal tasks (Chamberlain et al, 2009). Global depletion of serotonin (5-HT) leads to impulsivity in rats (Harrison et al, 1999; Masaki et al, 2006) and humans (Walderhaug et al, 2002). Although behavioral NoGo effects of serotonergic interventions are often mild or absent in humans, neuroimaging has revealed altered activity of underlying fronto-striatal circuits (Rubia et al, 2005; Evers et al, 2006). For example, acute tryptophan depletion (ATD) reduces frontal cortical activations (Rubia et al, 2005; Lamar et al, 2009), whereas the selective serotonin uptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram enhances them (Del-Ben et al, 2005).

There are marked individual differences in both impulsivity and serotonin. Impulsive clinical populations with serotonergic deficits include ADHD (Zepf et al, 2008), borderline personality disorder (Leyton et al, 2001), and frontotemporal dementia (Huey et al, 2006), whereas 5-HT2A receptor abnormalities have been linked to Tourette’s syndrome (Haugbol et al, 2007) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (Adams et al, 2005). Within the healthy population, variation in cerebral 5-HT2A receptor binding is partly genetically determined (Pinborg et al, 2008) with an influence on behavioral impulsivity (Nomura and Nomura, 2006) if not self-report impulsivity (Frokjaer et al, 2008). Individual differences may not be marked under normal testing conditions, but chronic serotonergic status (whether a genetically determined trait or a result of chronic environmental influences) may influence the change of impulsivity in response to acute challenges, such as stress, depression, or medication. This requires analysis of interactions between acute and chronic serotonergic states (including state–trait interactions) that we investigated in this study.

This study addressed two issues. The first aim was to better understand the functional, anatomical, and pharmacological basis of response inhibition. Our principal hypothesis was that chronic 5-HT2A receptor availability, inferred from 18F-altanserin steady-state binding measurements (BPP), influences the effect of acute state manipulations on response inhibition. Such an interaction would explain some of the behavioral and imaging differences between healthy individuals (Del-Ben et al, 2005; Rubia et al, 2005; Evers et al, 2006; Lamar et al, 2009) and patients (LeMarquand et al, 1998; Zepf et al, 2008). We studied healthy subjects with 18F-altanserin positron emission tomography (PET) and functional MRI sessions that differed only in 5-HT levels by (a) increased 5-HT neurotransmission by intravenous administration of the SSRI citalopram; (b) reduced brain 5-HT synthesis via acute dietary depletion of the 5-HT precursor tryptophan (ATD); (c) a control state without drug intervention. We were primarily interested in interactions between acute changes in serotonergic transmission, 5-HT2A BPp, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) correlates of response inhibition.

The second issue was to dissect cognitive components of the NoGo task and identify whether 5-HT specifically modulates the response inhibition component separable from other aspects of the task. For example, NoGo trials include low frequency events that trigger reflexive reorienting to task relevant stimuli, require greater cognitive control, and lead to response adjustment (Ridderinkhof et al, 2004; Kenner et al, 2010; Levy and Wagner, 2011). The response adjustment in classical NoGo trials is to withhold action, but the subjects might alternatively be asked to shift to a different response (Mostofsky and Simmonds, 2008). We therefore included a low frequency of trials in which subjects update to a different motor response (‘alternative go’, AltGo). We predicted that serotonergic manipulations would mainly influence the inhibitory component of the NoGo paradigm, revealed by differential activations between NoGo and AltGo trials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants, Task, and Pharmacological Challenges

Twenty-four right-handed adults (age 20–40 years) were recruited from a cohort of volunteers with 18F-altanserin PET brain imaging. Subjects were part of the Center for Integrated Molecular Brain Imaging (CIMBI) database that includes extensive enquiries into the participants’ past and present diagnosis or treatment of psychiatric illness. Based on these entry records, which were reconfirmed at study recruitment, we excluded subjects with a history of stimulant abuse, neurological disorder, or a psychiatric disorder requiring specialist referral or treatment. Written informed consent was obtained and the study approved by the Copenhagen Ethics Committee (KF01-2006–20). One subject was excluded due to an outlier 5-HT2A BPp value (>2.5 SD) identified on re-estimation of PET data following recruitment. This subject also had outlying error rates on the behavioral task (2.5–4 SD from the group mean). A second subject withdrew from the study before completion. Thus complete data sets from 22 participants (eight female participants, mean age±SD of 31.5±6.2) were included in further analyses.

Participants performed a modified NoGo task with three trial types: (a) ‘Go’ trials, pressing a button to a visual cue (yellow square); (b) AltGo, pressing a different button to a different visual cue (yellow circle); (c) ‘NoGo’, requiring no response (yellow triangle). Trial frequencies were 70, 15, and 15%, respectively. Stimuli were presented for 1000 ms with 500 ms intervals in a pseudorandom order during two blocks of 5 min.

Error rates and reaction times were entered into repeated measures analyses of variance (PASW-SPSS17 software, Chicago). Drug session and trial-type were within-subjects factors with three and two levels, respectively. 5-HT2A BPp was a between-subjects covariate. Huynh–Feldt correction for non-sphericity was used where appropriate and p<0.05 considered significant.

Subjects underwent three sessions of pharmacological fMRI, at least 1 week apart, and a fully counterbalanced order by pseudorandom permutation. The pharmacological conditions were: (a) Control session, without intervention; (b) SSRI session; and (c) ATD session. For SSRI sessions, citalopram was administered intravenously at 20 mg/h starting 2 h before scanning, with maintenance dose during the fMRI session at 8 mg/h (∼50 mg in total). For the ATD session, participants were asked to follow a low-protein diet on the day before scanning. On the test day, they ingested 75 g tryptophan-free powdered mixture of amino acids dissolved in water (XLYS, TRY Glutaridon, SHS International) and performed the fMRI session 5 h later. Blood samples were taken upon arrival and immediately before the fMRI to determine plasma amino acids and prolactin. The blood sample acted both as a control on our pharmacological treatments, and as a biochemical index of the serotonergic basis of imaging effects in the absence of marked behavioral change. Prolactin levels may be increased by acute tryptophan depletion in susceptible individuals (Wingrove et al, 1999) as they can by citalopram (Attenburrow et al, 2001; Del-Ben et al, 2005; McKie et al, 2005). In many previous studies, the behavioral and cognitive changes induced by ATD have been attributed to specific effects on the serotonergic system (Ardis et al, 2009). This view has been challenged recently (van Donkelaar et al, 2011), but we correlated the changes in tryptophan and prolactin with 5-HT2A BPp in support of the hypothesis that the ATD effect is at least partly due to effects on the serotonergic systems. On each of the fMRI sessions, participants completed a modified Danish version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire (McNair et al, 1971) thrice to assess current mood upon arrival immediately before fMRI and after completion of the tests.

18F-altanserin PET

18F-altanserin PET was used to estimate the subject-specific neocortical 5-HT2A receptor binding relative to plasma (BPp) using standardized published protocols (Pinborg et al, 2003; Adams et al, 2004; Svarer et al, 2005) and a maximum dose of 3.7 MBq/kg bodyweight. Reconstruction, attenuation, and scatter correction procedures were conducted according to this published protocol using cerebellum as a reference region (Pinborg et al, 2003). The outcome parameter for regional 5-HT2A receptor binding was the binding potential relative to plasma (BPp). To estimate regional BPp, PET images and structural T1-weighted MR images were co-registered (Adams et al, 2004) and normalized. We applied automatic parcelation of PET images using standardized volumes of interest delineated on transaxial MRI slices (Svarer et al, 2005) and derived neocortical estimates using the volume-weighted average of eight regions (orbitofrontal, medial inferior frontal, superior frontal, superior temporal, medial inferior temporal, sensory motor, parietal, and occipital cortex). As in a larger sample (Erritzoe et al, 2010), there were high correlations of BPP among cortical regions of interest (ROIs) (all r>0.8). We therefore used an average neocortical gray matter BPP for subsequent correlations with the functional MRI data (this correlated with BPP in the IFG, r>0.95).

MRI Acquisition and Analysis

We used a Siemens 3T Trio scanner with eight-channel head array coil for functional MRI with whole-brain coverage, high-resolution structural MRI, and arterial spin labeling (ASL) perfusion-weighted images. fMRI used BOLD-sensitive T2*-weighted echo-planar images (repetition time 2.5 s, echo time 26 ms, flip angle 90°) with 41 × 3 mm slices (25% gaps), 192 × 192 mm field-of-view. High-resolution 3D structural T1-weighted spin-echo images used an Magnetization-Prepared Rapid Acquisition Gradient Echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TI/TE/TR=800/3.93/1540 ms, flip angle 9°, 256 × 256 × 192 isotropic voxels). ASL perfusion-weighted images (TR=3.4 s, TE=19.3 ms, TI=200–3000, 200 ms intervals, 26 slices, voxel size=5.0 × 5.0 × 4.0 mm, 320 × 160 × 104 mm field-of-view) used vessel suppression with bipolar gradients (b=6 s/mm2). ASL images were calculated using FABBER with spatial priors (www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fabber) and permutations testing for differences between drug conditions.

Preprocessing and statistical analysis used SPM5 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm5). Functional images were realigned to the first volume and co-registered to the structural MPRAGE brain scan. The MPRAGE scan was normalized to a T1 template in standard space (MNI template) using linear and non-linear transformations. Normalization parameters were applied to functional volumes before smoothing with an isometric Gaussian kernel with full width half maximum 8 mm.

Subject-specific first-level general linear models of fMRI included four separate regressors for ‘Go’, ‘AltGo’, ‘NoGo’, and ‘NoGo commission errors’, and 40 nuisance regressors to correct for physiological noise related to pulse ( × 10), respiration ( × 6), and movement ( × 24) (Lund et al, 2005). Contrasts of interest were entered into group level random effects analyses using repeated measures ANOVA.

Two second-level flexible factorial models were used to examine main effects of trial-type and drug as well as interactions between individual differences and experimental conditions. The first model included regressors expressing ‘NoGo vs Go’ and ‘AltGo vs Go’ contrasts in each of three drug session (six total). This model also included mean corrected linear and quadratic functions of the average neocortical 5-HT2A BPP (12 total). These functions were separate for each drug condition (enabling the exploration of interactions between acute and chronic serotonergic functions). This model explains individual differences in terms of prior 5-HT2A BPp.

A second model included ‘subject’ as an additional factor with 22 subject-specifying regressors. This adjusts for individual subject differences that may or may not be related to trait serotonergic function, but prevents interpretation of the main effects of BPP (a between subjects factor). Both of the second-level ANOVAs were corrected for non-sphericity using pooled estimates of non-independent unequal variance over suprathreshold voxels.

For whole-brain comparisons, we applied family-wise error correction p<0.05. For hypotheses regarding the IFG, we defined a bilateral ROI that included the operculum and pars triangularis of the IFG (Automatic Anatomical Labeling and WFU-Pickatlas (Lancaster et al, 2000), and used ‘small volume correction’ family-wise error p<0.05. Owing to likely functional and anatomical heterogeneity within this IFG region, we report voxel-wise results and do not average responses across this region.

RESULTS

Behavior, Biochemistry, and Perfusion

Commission errors differed between NoGo and AltGo trials (Figure 1a; effect of trial-type F1, 20=5.0, p<0.05), but errors were similar across all three acute drug states (effect of drug F2, 40=2.5, ns). There was neither an interaction between trial-type and drug effects on error rates (F2, 40=2.3, ns) nor a higher order interaction between drug, trial-type, and 5-HT2A BPP (F2, 40=2.0, ns). Although there was no main effect of 5-HT2A BPP on error rate (F<1), there was an interaction between trial-type and 5-HT2A BPP (F1, 20=5.2, p<0.05) in their effect on error rates: 5-HT2A BPP correlated weakly positive with error rates in the NoGo trials (r(22)=0.26, ns) without a significant correlation on the AltGo trials (r(22)=−0.1, ns).

(a) Commission error rates (group mean and SD) on the NoGo and AltGo trials, under control condition (no drug) and after citalopram or ATD. (b) Reaction times (group mean and SD) for AltGo and Go trials, in the three drug sessions (Statistical analysis in results section: Behavior, biochemistry, and perfusion).

The reaction time was longer for AltGo than Go trials (F1, 20=6.7, p<0.05, Figure 1b). There was no main effect of drug (F<1, Figure 1b) or 5-HT2A BPP (F<1). There were no interactions between 5-HT2A BPP and trial-type or drug, and no high order interaction between all three factors (all F<1).

Baseline prolactin levels correlated highly between sessions (r=0.80, n=19, p<0.001). ANOVA of prolactin levels revealed no main effect of drug (F<1) or time within session from baseline to scanning (F1, 17=2.86, ns). There was however a trend of interaction between drug session and the change in prolactin from session baseline to onset of scanning (F1, 17=3.0, p<0.1, Figure 2a), such that prolactin only increased following citalopram. The 5-HT2A BPP did not correlate with prolactin levels (F<1) but did tend to influence the effect of drug on the change in prolactin between baseline and pre-scanning (F1, 17=3.3, p<0.1). Post hoc tests confirmed that higher 5-HT2A BPP was associated with a smaller change in prolactin after ATD (r=−0.39, n=21, p<0.05) but not after citalopram (r=0.0, ns). The ATD protocol reduced serum tryptophan levels by 75% (paired t-test, t=11.2, df=21, p<0.001, Figure 2b), suggesting reductions in central tryptophan bioavailability (Williams et al, 1999; Blokland et al, 2002).

(a) The difference in prolactin levels between baseline (T0) before administration of citalopram (Cit) or ATD and immediately prior to MRI scanning (T1). Group mean values with SEM. (b) ATD reduced serum tryptophan by 75%, comparable with previous studies of this method. Group mean values with SEM (Statistical analysis in results section: Behavior, biochemistry, and perfusion).

ASL showed no significant differences in cerebral perfusion during drug vs no-drug sessions, either with whole-brain analysis (FWE p<0.05 corrected) or within the IFG-ROI (FWE p<0.05 corrected or uncorrected threshold p<0.001).

An rmANOVA of the POMS questionnaire was conducted with two factors: 5-HT intervention (ATD, citalopram, and control) and time (at session baseline and after fMRI session). There was an effect of time for anger/hostility with lower scores after scanning compared to pre-scanning baseline (F(12)=6.98, p=0.02). There was no significant interaction between intervention and time in any of the reported mood states.

fMRI Results

Inhibiting vs updating a motor response

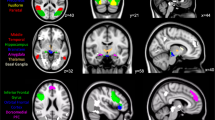

We first examined the low frequency events in which visual cues trigger reorientation to task relevant stimuli, invoke cognitive control, and a response adjustment, including (on NoGo trials) the inhibition of the prepotent response. Averaging ‘NoGo and AltGo vs Go’ trials across the three pharmacological sessions (Figure 3a) identified transient activations of prefrontal, premotor, parietal, and inferior occipitotemporal cortex, and extensive activation in the IFG bilaterally (Table 1, Figure 3a).

(a) SPM(t) map thresholded at FWE p<0.05 for the contrast of (NoGo and AltGo) trials vs Go trials. Further activations in IFG were seen within the predefined ROI (see text). Activations are rendered onto a representative brain in MNI space, in lateral views, and confirm the widespread differential activation following low frequency stimuli and resulting cognitive processes of control, updating, or inhibiting a response. (b) Activations of the IFG related to response inhibition, especially on the right, are revealed by the contrast of NoGo vs AltGo trials, here illustrated at p<0.001 (peaks are p<0.05 FWE corrected within the IFG region of interest). The inset slice shows right IFG at y=26. (c) Parameter estimates for voxel 40, 26, 4 in the right IFG (contrast of NoGo vs AltGo by drug session) under control (no drug), citalopram (cit) and ATD. (d) Parameter estimates for voxel 40, 26, 4 in right IFG for NoGo and AltGo trials (averaging over drug session). (e) Parameter estimates for voxel 40, 26, 4 in right IFG shown separately for each combination of drug and trial-type (NG=NoGo, Alt=AltGo, N=no drug, C=citalopram, A=ATD). Relative activation was greater for NoGo trials vs AltGo trials under control and citalopram sessions. Parameter estimates shown in C–E sum to zero across the group, from the flexible factorial design, and are scaled in arbitrary units. Pink error bars indicate 90% confidence intervals of the means.

Next, to identify activations related to inhibition, we compared regional activity between the NoGo and AltGo trials (‘NoGo vs AltGo’, averaging across all drug sessions, ROI analysis, Table 2, Figure 3b). There was differential activation of the right IFG (activations for each drug condition are shown in Figure 3c and for each trial-type in Figure 3d). In the right IFG, ATD abolished the differences between NoGo and AltGo trials (see below and Figure 3e).

The reverse contrast between AltGo and NoGo trials revealed activations associated with updating or switching a response in a broad ‘motor network’ of left motor and premotor cortex, right cerebellum, putamen, thalamus, and smaller clusters of activation in the left cingulate cortex, bilateral insula, and left cerebellum. Bilateral activations were also seen posterolaterally in the IFG bilaterally at the junctions between areas 6 and 44 (Table 3).

We looked for regions in which the effects of response inhibition and response updating were modulated by 5-HT2A BPP. For NoGo (vs Go) and for AltGo (vs Go) trials; no significant interactions were found. When examined separately for NoGo and AltGo trials (vs Go); there were no linear or quadratic effects of 5-HT2A BPP. The difference between NoGo and AltGo trials did not depend on 5-HT2A BPP when averaged across drug sessions.

Serotonergic challenges

Based on previous studies (Del-Ben et al, 2005; Rubia et al, 2005), we predicted that citalopram and ATD would have differential effects on activations associated with response inhibition. For the NoGo (vs Go) trials, there was greater activation in left IFG with citalopram than ATD (−48, 10, 12, t=3.97, 33 voxels, FWE p=0.05). For AltGo trials (vs Go), there were no significant interactions between response updating and citalopram vs ATD. However, the difference between NoGo and AltGo trials did not itself differ between citalopram and ATD sessions. In other words, for the inhibition of a response, but not the updating of a response, there were voxels in the left IFG that were differentially sensitive to citalopram and ATD. This was corroborated by an F-contrast testing the effect of either serotonergic challenge (vs no-drug or the other challenge) within either AltGo–Go or NoGo–Go contrast: identifying the left IFG at—48, 8, 12 (trend p<0.1 corrected, F4, 114=6.8).

We tested for interactions between the effects of serotonergic challenges and the 5-HT2A BPP, on activations associated with response inhibition and updating. SPM(t) contrasts were used to identify voxels in which BPP modulated the differential effect of citalopram or ATD (vs no-drug), for NoGo (vs Go), and for AltGo (vs Go). No significant voxels were identified by these contrasts using either whole-brain correction or just within the IFG ROI.

However, a higher order interaction was observed: the effect of ATD (ATD vs no-drug or ATD vs citalopram) on activations related to specific response inhibition (NoGo vs AltGo) depended on the 5-HT2A receptor BPP (Figure 4a) in the right IFG at 38, 14, 28 (F2, 114=13.18, p<0.05 FWE corrected within the ROI). Figure 4b shows parameter estimates for the relationship between 5-HT2A BPP and IFG activation as function of drug and trial-type. This means that the BPP level determined the effect of ATD on activations associated with inhibition in the NoGo trials (Figure 4c).

The inhibition of responses (NoGo vs AltGo) was associated with a variable degree of activation in the right IFG (peak voxel 38, 14, 28) according to the serotonergic challenge and the 5-HT2A BPP. Although citalopram did not differ from control sessions, the effect of ATD was reduced with increasing 5-HT2A BPP. (a) Surface rendered SPM(t) map (thresholded p<0.05 FWE within IFG) indicating the significant cluster in right IFG. (b) The parameter estimates for the two trial types at the peak right IFG voxel: NG=NoGo and Alt=AltGo, for each of the three drug sessions, N=No drug, C=citalopram, A=ATD. (c) The difference in bold response at the peak IFG voxel according to 5-HT2A BPP (normalized volume weighted mean neocortical 5-HT2A BPP from altanserin PET data) for each drug session. Linear regression lines are shown separately for each drug session, with post hoc correlations shown separately for each pharmacological challenge as R2. ATD differed significantly in slope from citalopram (p<0.05, corrected statistical inference from the SPM contrast).

DISCUSSION

We have shown that individual differences in neocortical 5-HT2A receptor binding are related to the subsequent effect of acute 5-HT manipulations on the neural correlates of the successful response inhibition in human IFG. We confirmed the association of NoGo inhibition with the IFG, and found that citalopram and ATD differentially modulated IFG activation for NoGo inhibition. In relation to our principal hypothesis, the novel finding was that the NoGo response in IFG under the different pharmacological challenges was differentially related to the neocortical 5-HT2A receptor binding. Critically, the interaction between 5-HT2A receptor binding and drug effects was confined to the difference in regional activity between the NoGo and AltGo trials, providing evidence for serotonergic modulation of the inhibitory component within the NoGo trials.

Response inhibition and switching to an alternative response did not elicit activations that correlated with 5-HT2A receptor binding. However, when contrasting these two trial types, the difference in error rates and the drug interaction with NoGo-specific activations both correlated with 5-HT2A receptor binding. Why were the effects of 5-HT2A BPP not more prominent, given the previous evidence for serotonergic modulation of inhibition? We suggest that long-term autoregulation of post-synaptic efficacy may reduce the baseline effects of 5-HT2A BPp on inhibitory control, at least within the normal range, and in contrast to the neuropsychiatric populations (Leyton et al, 2001; Huey et al, 2006; Zepf et al, 2008).

Although ATD did not result in a change in response times or accuracy, ATD produced a relatively larger response in the right IFG of subjects with low 5-HT2A BPP. Conversely, ATD reduced activation in right IFG in those with high 5-HT2A BPP. This differential response to ATD suggests a non-linear relationship between neocortical 5-HT and the efficiency of right IFG in response inhibition, with opposite effects of ATD in subjects with low vs high levels of 5-HT2A BPP. One implication is that drug effects may be exaggerated in some patients. For ATD, this appears to be the case for disorders of impulsivity (Leyton et al, 2001; Huey et al, 2006; Zepf et al, 2008) and mood (Ruhe et al, 2007). A corollary is that for subjects with very high 5-HT2A BPP, ATD might actually enhance the inhibition efficiency (LeMarquand et al, 1998).

How might such a non-linear response arise? In principle, it requires opposing downstream mechanisms driven by differential rates of 5-HT neurotransmission, for example, from two receptor subtypes with different affinity for an inhibitory autoreceptor. If the 5-HT2A BPP reflects the average serotonin level as determined by the raphe nucleus output (Erritzoe et al, 2010) then other receptor subtypes, most notably the inhibitory 5-HT1A receptor, may contribute to the interaction between ATD, IFG, and 5-HT2A BPP (Hannon and Hoyer, 2008).

The interactions between the acute serotonergic status (as induced by the drug interventions) and chronic serotonergic status (as indexed by neocortical 5-HT2A BPP) were localized to the IFG. To facilitate the interpretation of these effects, we identified the neural processes that are specifically related to withholding a prepotent response by comparing NoGo and AltGo trials. The restraint from a prepotent response (NoGo) was associated with activation of the right IFG, even after controlling for other factors including the presentation of low-frequency stimuli, processing of these task relevant stimulus attributes, engagement of additional cognitive control, and a change (update) of response.

The right IFG has been previously associated with switching to alternative responses and withholding responses (Kenner et al, 2010; Dodds et al, 2011). One interpretation is that updating to an alternate response utilizes the same neural systems as inhibition, but the critical process may instead be detection of behaviorally relevant cues (Hampshire et al, 2010) or increased response control demands (Dodds et al, 2011; Levy and Wagner, 2011). However, the IFG areas which were reported in previous studies include sites in the lateral prefrontal convexity and frontal operculum extending onto anterior insula. In this extended region we observed anatomical and pharmacological differences between AltGo and NoGo, although both trial-types require detection of salient cues. Interestingly, there were no main effects of drug on performance, but 5-HT2A levels affected error rates differentially between NoGo and AltGo trials. Although there was no effect of 5-HT2A on the AltGo condition, individuals with higher 5-HT2A levels showed increased error rates during NoGo trials.

AltGo cues prompted a switch of behavioral response. In prefrontal cortex, 5-HT is central to switching responses with feedback (Clarke et al, 2004) and response set shifting. However, an important distinction is that the NoGo/AltGo paradigm did not require a shift between attentional set or task set between trials. Both AltGo and NoGo trials were associated with activations in parietal, occipitotemporal, and supplementary motor area (SMA). AltGo was associated with greater activation in the motor network: motor, premotor, parietal cortex, striatum, and cerebellum. This is not simply due to the execution of movement in AltGo trials, as this network was more active for AltGo than Go trials. We suggest instead that late updating of a motor response is associated with either increased attention to action (Rowe et al, 2002) or co-activation of both standard and alternative motor programs. This latter interpretation is compatible with the hypothesis that AltGo trials induced a ‘race’ in the motor system between alternative responses (Logan et al, 1984).

The effects of citalopram on IFG activation were minimal in contrast with two previous studies (Del-Ben et al, 2005; Langenecker et al, 2007) and the effects of the 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist, mCPP (Anderson et al, 2002). The difference may be a type II error, despite a powerful repeated measures design, or differences in study populations. However, differences in drug regime must also be considered. For example, Del-Ben et al (2005) used a smaller total dose (7.5 mg during 7.5 min) than our infusion (∼50 mg during the entire session ∼3 h). The effects of high and low dose citalopram are not necessarily comparable. For example, in humans, low dose citalopram 5–10 mg increases prolactin levels from baseline and compared to placebo (Attenburrow et al, 2001; Del-Ben et al, 2005; McKie et al, 2005). However, the effects of 20 mg citalopram vary across studies (Henning and Netter, 2002; Pinborg et al, 2004) perhaps due to high variability of absolute increases and time to peak (Pinborg et al, 2004). Prolactin levels were only measured twice in our study, preventing us from capturing smaller or transient increases. The complex pharmacology of 5-HT and acute SSRIs may also explain the null result for citalopram: although acute citalopram increases cortical extracellular 5-HT at high doses (Moret and Briley, 1996), it may not translate into enhanced cortical post-synaptic stimulation with intermediate or low doses. This uncertainty is partly due to acute stimulation of somatodendritic 5-HT1A inhibitory autoreceptors in the raphe nucleus.

Despite the lack of effect of citalopram (vs no-drug), citalopram and ATD exerted significantly different effects on the inhibition signal expressed in left IFG, mirroring the IFG response reported previously (Del-Ben et al, 2005). This apparent laterality difference in thresholded activations across studies should not be interpreted as evidence of significant laterality effects in cognitive or neuronal functions (Henson, 2006). Indeed, lesion studies indicate bilateral IFG contributions to inhibition (Aron et al, 2003; Swick et al, 2008).

There are some limitations to our study. We did not use full placebo control of intravenous and oral challenges. Placebo effects, differential expectations, and non-specific drug induced changes in mood, nausea, or anxiety might contribute to the effects seen. In order to minimize the non-specific drug effects, we did not give subjects prior information about differences in side effects of the interventions. We also focus our interpretation on the contrast between the two interventions. The behavioral differences were found to be minimal and there were no differences in side effects (eg, nausea), and no differences between drug conditions in terms of self-rated mood. It is unlikely, therefore, that placebo effects can account for the functionally specific and anatomically specific effects observed. The correlations with serotonergic markers also confirm the serotonergic role in NoGo-type inhibition, over and above potential placebo effects. These factors together suggest that observed effects of ATD and citalopram are less likely to be due to differences in anxiety, discomfort, or nausea, even where these might theoretically be 5-HT-mediated. Although 5-HT2A receptor binding estimated from 18F-altanserin PET is stable over 2 years (Marner et al, 2009), the interval between PET and MRI in our subjects introduces additional variance. Moreover, despite clear heritability of 5-HT2A receptor binding (Pinborg et al, 2008), environmental factors may contribute to adult variance, and we cannot infer that the interactions between acute and chronic serotonergic factors are necessarily state–trait interactions. In addition, it may also be that citalopram’s behavioral effects are not mediated by 5-HT2A receptors, and therefore do not correlate with 5-HT2A receptor binding. As such, citalopram and ATD cannot be considered as simple opposite interventions. Finally, one must consider the potential confounds in pharmacological fMRI studies. By seeking ‘trial-type by drug’ interactions and regionally specific effects together with quantitative arterial spin labeling perfusion studies to exclude non-specific perfusion effects, we aimed to minimize such confounds.

Conclusions

The IFG was associated with response inhibition, and this effect was not fully attributable to the engagement of cognitive control and updating of a motor response following a low frequency stimulus. The activity of IFG that was associated with NoGo inhibition was itself modulated by the interaction between acute and chronic serotonergic factors. Specifically, the neural response to ATD depended on individual differences in 5-HT2A receptor binding, with implications for studies of clinical populations with abnormal 5-HT levels.

References

Adams KH, Hansen ES, Pinborg LH, Hasselbalch SG, Svarer C, Holm S et al (2005). Patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder have increased 5-HT2A receptor binding in the caudate nuclei. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 8: 391–401.

Adams KH, Pinborg LH, Svarer C, Hasselbalch SG, Holm S, Haugbol S et al (2004). A database of [(18)F]-altanserin binding to 5-HT(2A) receptors in normal volunteers: normative data and relationship to physiological and demographic variables. Neuroimage 21: 1105–1113.

Anderson IM, Clark L, Elliott R, Kulkarni B, Williams SR, Deakin JF (2002). 5-HT(2C) receptor activation by m-chlorophenylpiperazine detected in humans with fMRI. Neuroreport 13: 1547–1551.

Ardis TC, Cahir M, Elliott JJ, Bell R, Reynolds GP, Cooper SJ (2009). Effect of acute tryptophan depletion on noradrenaline and dopamine in the rat brain. J Psychopharmacol 23: 51–55.

Aron AR, Fletcher PC, Bullmore ET, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW (2003). Stop-signal inhibition disrupted by damage to right inferior frontal gyrus in humans. Nat Neurosci 6: 115–116.

Asahi S, Okamoto Y, Okada G, Yamawaki S, Yokota N (2004). Negative correlation between right prefrontal activity during response inhibition and impulsiveness: a fMRI study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 254: 245–251.

Attenburrow MJ, Mitter PR, Whale R, Terao T, Cowen PJ (2001). Low-dose citalopram as a 5-HT neuroendocrine probe. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 155: 323–326.

Blokland A, Lieben C, Deutz NE (2002). Anxiogenic and depressive-like effects, but no cognitive deficits, after repeated moderate tryptophan depletion in the rat. J Psychopharmacol 16: 39–49.

Chamberlain SR, Hampshire A, Muller U, Rubia K, Del Campo N, Craig K et al (2009). Atomoxetine modulates right inferior frontal activation during inhibitory control: a pharmacological functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry 65: 550–555.

Chikazoe J, Jimura K, Asari T, Yamashita K, Morimoto H, Hirose S et al (2009). Functional dissociation in right inferior frontal cortex during performance of go/no-go task. Cereb Cortex 19: 146–152.

Chikazoe J, Konishi S, Asari T, Jimura K, Miyashita Y (2007). Activation of right inferior frontal gyrus during response inhibition across response modalities. J Cogn Neurosci 19: 69–80.

Clarke HF, Dalley JW, Crofts HS, Robbins TW, Roberts AC (2004). Cognitive inflexibility after prefrontal serotonin depletion. Science 304: 878–880.

Del-Ben CM, Deakin JF, McKie S, Delvai NA, Williams SR, Elliott R et al (2005). The effect of citalopram pretreatment on neuronal responses to neuropsychological tasks in normal volunteers: an FMRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology 30: 1724–1734.

Dodds CM, Morein-Zamir S, Robbins TW (2011). Dissociating inhibition, attention, and response control in the frontoparietal network using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb Cortex 21: 1155–1165.

Eagle DM, Bari A, Robbins TW (2008). The neuropsychopharmacology of action inhibition: cross-species translation of the stop-signal and go/no-go tasks. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 199: 439–456.

Erritzoe D, Holst K, Frokjaer VG, Licht CL, Kalbitzer J, Nielsen FA et al (2010). A nonlinear relationship between cerebral serotonin transporter and 5-HT(2A) receptor binding: an in vivo molecular imaging study in humans. J Neurosci 30: 3391–3397.

Evers EA, van der Veen FM, van Deursen JA, Schmitt JA, Deutz NE, Jolles J (2006). The effect of acute tryptophan depletion on the BOLD response during performance monitoring and response inhibition in healthy male volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 187: 200–208.

Frokjaer VG, Mortensen EL, Nielsen FA, Haugbol S, Pinborg LH, Adams KH et al (2008). Frontolimbic serotonin 2A receptor binding in healthy subjects is associated with personality risk factors for affective disorder. Biol Psychiatry 63: 569–576.

Hampshire A, Chamberlain SR, Monti MM, Duncan J, Owen AM (2010). The role of the right inferior frontal gyrus: inhibition and attentional control. Neuroimage 50: 1313–1319.

Hannon J, Hoyer D (2008). Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors. Behav Brain Res 195: 198–213.

Harrison AA, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW (1999). Central serotonin depletion impairs both the acquisition and performance of a symmetrically reinforced go/no-go conditional visual discrimination. Behav Brain Res 100: 99–112.

Haugbol S, Pinborg LH, Regeur L, Hansen ES, Bolwig TG, Nielsen FA et al (2007). Cerebral 5-HT2A receptor binding is increased in patients with Tourette’s syndrome. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 10: 245–252.

Henning J, Netter P (2002). Oral application of citalopram (20 mg) and its usefulness for neuroendocrine challenge tests. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 5: 67–71.

Henson R (2006). Forward inference using functional neuroimaging: dissociations versus associations. Trends Cogn Sci 10: 64–69.

Huey ED, Putnam KT, Grafman J (2006). A systematic review of neurotransmitter deficits and treatments in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 66: 17–22.

Iversen SD, Mishkin M (1970). Perseverative interference in monkeys following selective lesions of the inferior prefrontal convexity. Exp Brain Res 11: 376–386.

Kenner NM, Mumford JA, Hommer RE, Skup M, Leibenluft E, Poldrack RA (2010). Inhibitory motor control in response stopping and response switching. J Neurosci 30: 8512–8518.

Konishi S, Nakajima K, Uchida I, Kikyo H, Kameyama M, Miyashita Y (1999). Common inhibitory mechanism in human inferior prefrontal cortex revealed by event-related functional MRI. Brain 122: 981–991.

Konishi S, Nakajima K, Uchida I, Sekihara K, Miyashita Y (1998). No-go dominant brain activity in human inferior prefrontal cortex revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Neurosci 10: 1209–1213.

Lamar M, Cutter WJ, Rubia K, Brammer M, Daly EM, Craig MC et al (2009). 5-HT, prefrontal function and aging: fMRI of inhibition and acute tryptophan depletion. Neurobiol Aging 30: 1135–1146.

Lancaster J, Woldorff M, Parsons L, Liotti M, Freitas C, Rainey L et al (2000). Automated Talairach atlas labels for functional brain mapping. Hum Brain Mapp 10: 120–131.

Langenecker SA, Kennedy SE, Guidotti LM, Briceno EM, Own LS, Hooven T et al (2007). Frontal and limbic activation during inhibitory control predicts treatment response in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 62: 1272–1280.

LeMarquand DG, Pihl RO, Young SN, Tremblay RE, Seguin JR, Palmour RM et al (1998). Tryptophan depletion, executive functions, and disinhibition in aggressive, adolescent males. Neuropsychopharmacology 19: 333–341.

Levy BJ, Wagner AD (2011). Cognitive control and right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex: reflexive reorienting, motor inhibition, and action updating. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1224: 40–62.

Leyton M, Okazawa H, Diksic M, Paris J, Rosa P, Mzengeza S et al (2001). Brain regional alpha-[11C]methyl-L-tryptophan trapping in impulsive subjects with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 158: 775–782.

Logan GD, Cowan WB, Davis KA (1984). On the ability to inhibit simple and choice reaction time responses: a model and a method. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 10: 276–291.

Lund TE, Norgaard MD, Rostrup E, Rowe JB, Paulson OB (2005). Motion or activity: their role in intra- and inter-subject variation in fMRI. Neuroimage 26: 960–964.

Marner L, Knudsen GM, Haugbol S, Holm S, Baare W, Hasselbalch SG (2009). Longitudinal assessment of cerebral 5-HT2A receptors in healthy elderly volunteers: an (18F)-altanserin PET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 36: 287–293.

Masaki D, Yokoyama C, Kinoshita S, Tsuchida H, Nakatomi Y, Yoshimoto K et al (2006). Relationship between limbic and cortical 5-HT neurotransmission and acquisition and reversal learning in a go/no-go task in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 189: 249–258.

McKie S, Del-Ben C, Elliott R, Williams S, del Vai N, Anderson I et al (2005). Neuronal effects of acute citalopram detected by pharmacoMRI. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 180: 680–686.

McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman L (1971) Manual for the Profile of Mood States. Educational and Industrial Testing Services: San Diego, CA.

Moret C, Briley M (1996). Effects of acute and repeated administration of citalopram on extracellular levels of serotonin in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol 295: 189–197.

Mostofsky SH, Simmonds DJ (2008). Response inhibition and response selection: two sides of the same coin. J Cogn Neurosci 20: 751–761.

Nomura M, Nomura Y (2006). Psychological, neuroimaging, and biochemical studies on functional association between impulsive behavior and the 5-HT2A receptor gene polymorphism in humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1086: 134–143.

Pinborg LH, Adams KH, Svarer C, Holm S, Hasselbalch SG, Haugbol S et al (2003). Quantification of 5-HT2A receptors in the human brain using [18F]altanserin-PET and the bolus/infusion approach. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 23: 985–996.

Pinborg LH, Adams KH, Yndgaard S, Hasselbalch SG, Holm S, Kristiansen H et al (2004). (18F)altanserin binding to human 5HT2A receptors is unaltered after citalopram and pindolol challenge. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 24: 1037–1045.

Pinborg LH, Arfan H, Haugbol S, Kyvik KO, Hjelmborg JV, Svarer C et al (2008). The 5-HT2A receptor binding pattern in the human brain is strongly genetically determined. Neuroimage 40: 1175–1180.

Ridderinkhof KR, van den Wildenberg WP, Segalowitz SJ, Carter CS (2004). Neurocognitive mechanisms of cognitive control: the role of prefrontal cortex in action selection, response inhibition, performance monitoring, and reward-based learning. Brain Cogn 56: 129–140.

Rowe J, Friston K, Frackowiak R, Passingham R (2002). Attention to action: specific modulation of corticocortical interactions in humans. Neuroimage 17: 988–998.

Rubia K, Lee F, Cleare AJ, Tunstall N, Fu CH, Brammer M et al (2005). Tryptophan depletion reduces right inferior prefrontal activation during response inhibition in fast, event-related fMRI. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 179: 791–803.

Rubia K, Russell T, Overmeyer S, Brammer MJ, Bullmore ET, Sharma T et al (2001). Mapping motor inhibition: conjunctive brain activations across different versions of go/no-go and stop tasks. Neuroimage 13: 250–261.

Ruhe HG, Mason NS, Schene AH (2007). Mood is indirectly related to serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine levels in humans: a meta-analysis of monoamine depletion studies. Mol Psychiatry 12: 331–359.

Simmonds DJ, Pekar JJ, Mostofsky SH (2008). Meta-analysis of Go/No-go tasks demonstrating that fMRI activation associated with response inhibition is task-dependent. Neuropsychologia 46: 224–232.

Svarer C, Madsen K, Hasselbalch SG, Pinborg LH, Haugbol S, Frokjaer VG et al (2005). MR-based automatic delineation of volumes of interest in human brain PET images using probability maps. Neuroimage 24: 969–979.

Swann N, Tandon N, Canolty R, Ellmore TM, McEvoy LK, Dreyer S et al (2009). Intracranial EEG reveals a time- and frequency-specific role for the right inferior frontal gyrus and primary motor cortex in stopping initiated responses. J Neurosci 29: 12675–12685.

Swick D, Ashley V, Turken AU (2008). Left inferior frontal gyrus is critical for response inhibition. BMC Neurosci 9: 102.

van Donkelaar EL, Blokland A, Ferrington L, Kelly PA, Steinbusch HW, Prickaerts J (2011). Mechanism of acute tryptophan depletion: is it only serotonin? Mol Psychiatry 16: 695–713.

Wager TD, Sylvester CY, Lacey SC, Nee DE, Franklin M, Jonides J (2005). Common and unique components of response inhibition revealed by fMRI. Neuroimage 27: 323–340.

Walderhaug E, Lunde H, Nordvik JE, Landro NI, Refsum H, Magnusson A (2002). Lowering of serotonin by rapid tryptophan depletion increases impulsiveness in normal individuals. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 164: 385–391.

Williams WA, Shoaf SE, Hommer D, Rawlings R, Linnoila M (1999). Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on plasma and cerebrospinal fluid tryptophan and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in normal volunteers. J Neurochem 72: 1641–1647.

Wingrove J, Bond AJ, Cleare AJ, Sherwood R (1999). Trait hostility and prolactin response to tryptophan enhancement/depletion. Neuropsychobiology 40: 202–206.

Zepf FD, Holtmann M, Stadler C, Demisch L, Schmitt M, Wockel L et al (2008). Diminished serotonergic functioning in hostile children with ADHD: tryptophan depletion increases behavioural inhibition. Pharmacopsychiatry 41: 60–65.

Zheng D, Oka T, Bokura H, Yamaguchi S (2008). The key locus of common response inhibition network for no-go and stop signals. J Cogn Neurosci 20: 1434–1442.

Acknowledgements

The Lundbeck Foundation is gratefully acknowledged for their financial support of the study. Dr Fin S Larsen, Department of Hepatology, Rigshospitalet, is thanked for providing measurements of serum tryptophan. SHS International Ltd, Liverpool, UK is acknowledged for providing the tryptophan-free amino acid mixture. JBR is supported by the Wellcome Trust (088324).Financial support was provided primarily from the Lundbeck Foundation to the Center for Integrated Molecular Brain Imaging (Cimbi). The John and Birthe Meyer Foundation donated funding for PET-scanner and cyclotron. The Copenhagen University Hospitals Rigshospitalet and Hvidovre also supported the study. The Spies foundation donated funding to the 3 T Trio MRI scanner. HRS was supported by a grant of excellence by the Lundbeck Foundation on the Control of Action (ContAct, Grant no. R59 A5399).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

HRS has received honoraria as reviewing editor for Neuroimage, as speaker for Biogen Idec Denmark A/S, and scientific Advisor from Lundbeck A/S, Valby, Denmark. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Macoveanu, J., Hornboll, B., Elliott, R. et al. Serotonin 2A Receptors, Citalopram and Tryptophan-Depletion: a Multimodal Imaging Study of their Interactions During Response Inhibition. Neuropsychopharmacol 38, 996–1005 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2012.264

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2012.264

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Mapping neuromodulatory systems in Parkinson’s disease: lessons learned beyond dopamine

Current Medicine (2022)

-

Dissociable effects of acute SSRI (escitalopram) on executive, learning and emotional functions in healthy humans

Neuropsychopharmacology (2018)

-

The neurobiology of impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: from neurotransmitters to neural networks

Cell and Tissue Research (2018)

-

Auditory evoked potential could reflect emotional sensitivity and impulsivity

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Amino acid challenge and depletion techniques in human functional neuroimaging studies: an overview

Amino Acids (2015)