Abstract

We conducted meta-analyses of findings from randomized, placebo-controlled, short-term trials for acute mania in manic or mixed states of DSM (III–IV) bipolar I disorder in 56 drug–placebo comparisons of 17 agents from 38 studies involving 10 800 patients. Of drugs tested, 13 (76%) were more effective than placebo: aripiprazole, asenapine, carbamazepine, cariprazine, haloperidol, lithium, olanzapine, paliperdone, quetiapine, risperidone, tamoxifen, valproate, and ziprasidone. Their pooled effect size for mania improvement (Hedges’ g in 48 trials) was 0.42 (confidence interval (CI): 0.36–0.48); pooled responder risk ratio (46 trials) was 1.52 (CI: 1.42–1.62); responder rate difference (RD) was 17% (drug: 48%, placebo: 31%), yielding an estimated number-needed-to-treat of 6 (all p<0.0001). In several direct comparisons, responses to various antipsychotics were somewhat greater or more rapid than lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine; lithium did not differ from valproate, nor did second generation antipsychotics differ from haloperidol. Meta-regression associated higher study site counts, as well as subject number with greater placebo (not drug) response; and higher baseline mania score with greater drug (not placebo) response. Most effective agents had moderate effect-sizes (Hedges’ g=0.26–0.46); limited data indicated large effect sizes (Hedges’ g=0.51–2.32) for: carbamazepine, cariprazine, haloperidol, risperidone, and tamoxifen. The findings support the efficacy of most clinically used antimanic treatments, but encourage more head-to-head studies and development of agents with even greater efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

For decades, lithium and chlorpromazine were the only medicines with regulatory approval for acute mania, although many others were used empirically (Baldessarini and Tarazi, 2005). These included many neuroleptics (first generation antipsychotics (FGAs)) and potent benzodiazepines, used empirically with very limited support from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Anticonvulsants, including carbamazepine and valproate, have been widely used since the 1980s. Growing numbers of novel antimanic agents have emerged in recent years, including second generation antipsychotics (SGAs), several anticonvulsants, and the antiestrogenic, central protein kinase-C (PKC) inhibitor tamoxifen. Currently, all SGAs (except clozapine), as well as lithium and the anticonvulsants valproate and carbamazepine are FDA approved for treatment of acute bipolar mania.

Placebo-controlled RCTs for newer antimanic drugs have increased greatly in the past decade, but relatively little information is available about how these compounds or pharmacologically similar groups of them compare in efficacy, or about types of patients most likely to benefit from particular treatments. Recently, the efficacy of some psychotropic agents for treating some mental disorders has been questioned. For example, in their evaluation of antidepressants for major depressive disorder (MDD), Moncrieff and Kirsch (2005) found only a two point difference between drug and placebo on the Hamilton rating scale for depression. Leucht et al (2009) in a meta-analytic review of 38 studies reported a difference of only nine points on the brief psychiatric rating scale between SGAs and placebo in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. The few previous meta-analytic assessments of relative efficacy of treatments for mania usually involved selective consideration of agents of particular interest, and none has considered outcomes of all available RCTs, as identified through clinical trial registries (Emilien et al, 1996; Perlis et al, 2006b; Scherk et al, 2007; Smith et al, 2007; Tohen et al, 2001). Indeed, bias toward reporting favorable trials, as well as alleged delays or failure to report details of trials not showing separation of a novel treatment from placebo, probably have limited or biased information available (Vieta and Cruz, 2008). As pharmaceutical companies are now expected to post the design of trials before they are conducted, and to publish results promptly, it has become more feasible to attempt comprehensive meta-analyses.

To evaluate efficacy of available drugs compared with placebo for treating acute mania we now present results of primary meta-analyses of 38 monotherapy studies that included 56 drug–placebo comparisons involving 10 800 manic patient subjects. We tested for possible effects of study site counts, sample sizes, and initial illness severity on trial outcomes. We also secondarily considered available direct (head-to-head) comparisons of similar groups of agents.

METHODS

Data Sources

We performed comprehensive searches of the literature, using PubMed/Medline; ClinicalTrials.gov; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; Controlled-trials.com; and EMBASE/Excerpta Medica databases for RCTs for acute mania in bipolar disorder (last search: 12 January 2010). Search terms were: ‘bipolar, mania, trial’, and names of individual antipsychotic, anticonvulsant, or other drugs. We also reviewed reports in proceedings of meetings of the American and European Colleges of Neuropsychopharmacology, American Psychiatric Association, American College of Psychiatry, and International Conference on Bipolar Disorder since 1990, as well as references from all sources. We also consulted investigators identified as having studied antimania agents, as well as representatives of pharmaceutical companies that market such drugs to identify reports of additional trials, or for information missing from identified reports.

Study Selection

Among initially identified potential studies, we selected monotherapy trials with random assignment to treatment arms that prospectively compared a test agent with placebo or a standard comparator. Therapeutic targets were manic symptoms of acute mania or mixed manic depressive states of adult bipolar I disorder as defined by DSM-IIIR, -IV, or -IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association (APA), (2000)), or research diagnostic criteria (RDC; Spitzer et al, 1978). Manic symptoms were rated at baseline and during treatment with a standard rating scale (usually the Young mania rating scale (11-item YMRS, scoring range: 0–60; Young et al, 1978) or mania rating scale (11-item MRS, range: 0–52; Endicott and Spitzer, 1978), which are similar in scoring and apparent responsiveness to treatment effects (Perlis et al, 2006b). Trials using other symptom rating methods, or participants diagnosed with bipolar II, unspecified (NOS), or schizoaffective disorders were excluded, as were studies without a placebo or standard comparator, or permitting psychotropic agents other than moderate doses of benzodiazepines or chloral hydrate. Double-blind design was required for placebo-controlled studies. However, as omparison trials are uncommon, we included several randomized but unblinded head-to-head trials in secondary analyses. We included data from all registered and completed placebo-controlled trials of acute mania, except two recent studies involving calcium channel blocker MEM-1003 and clozapine, considered by the investigators as not yet ready for public disclosure.

Data Extraction and Outcome Measures

Information collected included study site counts; proportions of women and men randomized as well as with at least one assessment during treatment (intent-to-treat (ITT) samples); type of presentation (mania or mixed manic depressive states, with or without psychotic features); baseline mania severity (total score and percentage of maximum possible scale score) and mean doses (mg/day) of experimental agents; measures of initial and final group mean mania ratings; nominal study duration; and completion rates for each trial arm. Data were extracted by two reviewers (AY and SÖ) to meet consensus.

The primary outcome of interest was the Hedges’ adjusted g, based on the standardized mean difference between changes in mania ratings with test drug vs placebo or a standard comparator (Borenstein et al, 2009). A secondary outcome measure was the rate of attaining response (defined in nearly all studies as ⩾50% reduction of initial mania scores from baseline to end point).

Meta-Analytic Calculations

We combined outcome data across trials with standard meta-analytic methods. For continuous data (changes in mean mania scores from individual trials), we employed the standardized mean difference: Hedges’ adjusted g (a slightly modified version of Cohen’ D, also generally used by the Cochrane collaboration), as it transforms all effect sizes from individual studies to a common metric and enables inclusion of different outcome measures in the same synthesis (Borenstein et al, 2009). When standard deviations (SD) for change in mean mania scores were not reported, we estimated pooled SD by using standard statistical procedures (Whitley and Ball, 2002). For categorical responder rates, we used risk ratio (RR: response with drug treatment vs placebo or a standard comparator) and absolute difference in responder rates (rate difference (RD)), with the associated number-needed-to-treat (NNT (1/RD): the estimated number of patients to be treated with a drug versus a placebo or standard comparator for one additional patient to benefit (NNTbenefit) or be harmed (NNTharm); Altman, 1988; Borenstein et al, 2009). Numerical results are presented with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). As the true effects in the trials analyzed were assumed to have been sampled from a distribution of true effects we used random effects meta-analyses, with or without evidence of heterogeneity based on Q and I2 statistics (Borenstein et al, 2009; Der Simonian and Laird, 1986).

We also used meta-regression (with unrestricted maximum likelihood, mixed effects modeling) to evaluate impact on Hedges’ g for drug–placebo comparisons (outcome) of pre-selected factors: study site count, sample size, and baseline mania severity. This variant of multiple regression modeling weights for subject number/arm and variance measures to compute regression equations. The slope (β-coefficient: direct (+) or inverse (−)) of the regression line indicates the strength of a relationship between moderator and outcome. To limit risk of false-positive (type I) errors arising from multiple comparisons we adjusted p<0.05 by dividing α with the number of meta-regressions.

Studies with relatively large drug–placebo differences may be more likely to be reported, resulting in publication-bias that typically overestimates effect size (Borenstein et al, 2009). We examined potential publication bias with funnel plot of pooled effect size vs its standard error (Sterne and Egger, 2001). We also estimated fail safe N values (number of additional hypothetical studies with zero effect that would make summary effect in meta-analysis trivial, defined as Hedges’ g<0.10; Orwin, 1983). Finally, we used Duval and Tweedie's (2000) trim and fill approach to provide best estimate of unbiased effect size by removing the smallest studies sequentially until funnel plots became symmetrical about adjusted effect size. For data analyses, we used Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, version 2.2 (BioStat, Englewood, NJ). Statistical significance required two-tailed p<0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Trials and Subjects

Primary meta-analyses included 56 randomized, double-blind comparisons (13 with negative results) of 17 drugs versus placebo from 38 studies involving a total of 13 093 randomized and 12 920 ITT manic patient subjects (Table 1). Corrected for duplicate counting of placebo arm patients who appear more than once in multiarm trials, 6988 manic patients were randomized to active agents and 3812 to placebo, with at least one follow-up assessment (total n=10 800 ITT patients). Mania symptom ratings used YMRS in 45/56 trials (80.4%), and MRS in 11/56 (19.6%). Most studies (34/38: 89.5%) involved multiple collaborating sites (mean: 29.7±18.9 sites/study; range: 1–70). Manufacturers of tested agents sponsored 89.5% of studies. Placebo-associated improvement in mean mania ratings relative to baseline varied greatly, from −19% (Zarate et al, 2007) or +0.63% (Pope et al, 1991) to +38% (McIntyre et al, 2009a). Likewise, study drop-out rates ranged from 13–15% (Kushner et al, 2006; Smulevich et al, 2005, respectively) to 82% (Hirschfeld et al, 2010) with placebo, and from 11–14% (Bowden et al, 2005; Khanna et al, 2005; Smulevich et al, 2005) to 83% (Hirschfeld et al, 2010) with drug. The impact of these sources of variance lie beyond this study and are reported separately (Yildiz et al, 2010). Of the 11 072 randomized subjects (corrected for duplicate counting in placebo arms), 5603 (50.6%) were men, and age averaged 39.1±11.7 years. Diagnostic criteria followed DSM-IV or -IV-TR in 92.1% of 38 studies, and less often, DSM-IIIR (5.3%) or RDC criteria (2.6%). Most subjects (73.1%) were diagnosed with mania, whereas 26.5% randomized to drugs and 27.1% given placebo were considered to be in a mixed manic depressive state. However, responses of men vs women, specific age groups, those diagnosed with mania vs mixed states, or outcomes at specific sites were rarely reported separately, precluding direct comparisons. Psychotic features at intake were noted in 29.3% of subjects (28.0% given drugs and 31.8% given placebo). Nominal trial duration was 3 weeks in 97.4% of studies (considered sufficient for regulatory approval; Table 1). However, rates of protocol completion averaged 65.8% with active agents (34.2% dropout) and 57.4% with placebo (42.6% dropout), in 36/38 studies providing such data, indicating that actual treatment exposure was close to 2 weeks.

Secondary meta-analyses involved comparison of a test agent with an established comparison-control drug (with or without a placebo arm), assigned randomly in 31 studies with 33 comparisons (31 (93.9%) double-blind) involving 13 drugs and a total of 6710 manic patients as the ITT sample corrected for duplicate counting of placebo arms (Table 2). These trials rated mania with the YMRS in 77.4%, and MRS in 22.6% of the 31 studies. Multiple sites were involved in 80.6% of these 31 trials (averaging 30.4±23.8 (1–76) sites/study), and drug manufacturers sponsored 77.4% of them. Nominal trial duration was 3 weeks in 21 studies (67.7%) and protocol completion averaged 73.4% (26.6% drop out; Table 2).

Comparisons of Individual Drugs vs Placebo

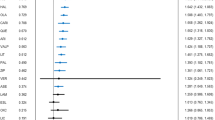

Meta-analysis indicated statistical superiority over placebo for 13/17 agents tested: aripiprazole (n=1662 subjects), asenapine (n=569), carbamazepine (n=427), cariprazine (n=235), haloperidol (n=1051), lithium (n=1199), olanzapine (n=1335), paliperdone (n=1001), quetiapine (n=1007), risperidone (n=823), tamoxifen (n=74), valproate (n=1046), and ziprasidone (n=663); and lack of efficacy in four others: lamotrigine (n=179), licarbazepine (n=313), topiramate (n=1074), and verapamil (n=20; Table 1; Figure 1). For the 13 effective drugs, the pooled effect size was moderate (in 48 trials involving 11 092 patients, Hedges’ g=0.42, 95% CI: 0.36–0.48; p<0.0001). On contrast, four agents with non-significant summary effects yielded a pooled effect size of <0.10 in seven trials with 1586 subjects (Hedges’ g= −0.03, CI: −0.13 to +0.08; p=0.62). For categorical responder rates, pooled RR for the 13 effective drugs was 1.52 (CI: 1.42–1.62) in 46 trials with 10 669 subjects (p<0.0001), and only 0.98 (CI: 0.82–1.19) in 7 trials of the 4 apparently ineffective agents with 1586 subjects (p=0.87; Table 3).

Forest plot of Hedges’ g with its 95% upper and lower limits (confidence interval (CI)), based on mania score changes in 55 drug/placebo comparisons, based on random effects meta-analysis. Filled squares indicate pooled results of individual drugs (and their CI). Drugs are listed according to the magnitude of the pooled effect sizes (Hedges’ g).

Comparisons of Drug Classes vs Placebo

On the basis of primary outcome measure Hedges’ g, as a measure of improvement of mania ratings between drugs and placebo, SGAs as a group yielded an overall effect size of 0.40 (CI: 0.32–0.47 in 29 trials involving 7295 patients; p<0.0001). For mood stabilizers (MSs, including carbamazepine, lithium, and valproate), pooled effect size was 0.38 (CI: 0.26–0.50 in 13 trials involving 2672 patients; p<0.0001). The unique central PKC-inhibiting drug tamoxifen yielded an unusually large Hedges’ g of 2.32 (CI: 1.66–2.99; p<0.0001) in two small trials involving a total of 74 patients. Studies involving haloperidol as a standard active comparator (FGA), in its direct comparisons with placebo, yielded a pooled Hedges’ g of 0.54 (CI: 0.34–0.74; p<0.0001) in four trials with 1051 subjects.

With respect to categorical responder rates (Table 3), SGAs vs placebo yielded a pooled RR of 1.47 (CI: 1.36–1.59; 28 trials, 7094 patients, p<0.0001); MSs, as a group yielded pooled RR of 1.59 (CI: 1.39–1.82; 12 trials, 2450 patients, p<0.0001), again indicating similar summary effects and CIs. Tamoxifen yielded an unusually high RR of 7.46 (CI: 1.88–29.7; 2 trials, 74 patients, p=0.004). For haloperidol, RR was 1.58 (CI: 1.29–1.94; 4 trials, 1051 patients, p<0.0001). Estimates of NNTbenefit values (smaller NNT with greater efficacy) ranked: tamoxifen <haloperidol <MSs <SGAs (Table 3).

Direct Comparisons

On the basis of the improvement in mania ratings (Hedges’ g; Table 4), SGAs as a group yielded greater effect size than MSs (in eight trials with 1464 patients, Hedges’ g=0.17, CI: 0.07–0.28, p=0.001). Similarly, comparison of MSs vs all antipsychotics tested (SGAs or haloperidol) also favored the antipsychotics (Hedges’ g=0.18, CI: 0.08–0.28 in 10 trials with 1530 subjects, p<0.0001), and SGAs did not differ from haloperidol (Hedges’ g= −0.001, CI: −0.24 to +0.24 in six trials with 1536 subjects, p=0.99). Similarly, valproate and lithium did not differ significantly (Hedges’ g=0.11, CI: −0.04 to +0.26 in four trials with 679 subjects, p=0.16).

On the basis of categorical responder rates in direct comparisons (Table 4), SGAs again appeared to be somewhat more effective than MSs (RR=0.88, CI: 0.80–0.96, in six trials with 1443 subjects, p=0.006). Antipsychotics (SGAs or haloperidol) were similarly superior to, or faster acting than, MSs (RR=0.88, CI: 0.80–0.97, in seven trials with 1479, p=0.01). Direct comparisons of haloperidol (the only FGA tested) with SGAs indicated little or no difference (RR=0.93, CI: 0.79–1.10, in seven trials with 2166 patients, p=0.40), as did lithium vs valproate (RR=1.00, CI: 0.81–1.24, in four trials with 679 patients, p=1.00).

Factors Associated with Drug–Placebo Contrasts

Overall inter-study variance in effect sizes of drug–placebo contrasts was substantial (Q=47.6, df=12, p<0.0001; I2=70.4), encouraging consideration of possible explanatory factors. In regression models involving drug arms, we considered only the 13 agents found more effective than placebo, so as to avoid potential confounding by drug inefficacy, which itself would influence treatment effects (drug–placebo contrasts). We tested pre-selected covariates (study site counts, sample size, and initial manic symptom severity) for possible association with observed effect size (Hedges’ g) as a measure of treatment effect (difference in improvements in mania ratings between drug versus placebo), and mean difference (change in mania scores between baseline and final rating) to indicate drug or placebo effects. With these three covariates, statistical significance set at two-tailed α=0.016 (0.05/3).

We found significant associations between higher number of collaborating study sites and smaller treatment effects (drug versus placebo: 48 trials; slope (β)=–0.007, CI: −0.01 to −0.003, z= −3.79, p=0.00015), as well as larger placebo effects (38 trials; β=+0.11, CI: 0.06–0.15, z=4.67, p<0.0001), but not drug effects (48 trials; β= −0.02, CI: −0.06 to +0.03, z= −0.80, p=0.43). As more study sites corresponds with larger patient samples, we found similar associations between larger sample sizes and smaller treatment effects (48 trials; slope (β)= −0.001, CI: −0.003 to −0.0004, z= −2.63, p=0.008), and larger placebo effects (38 trials; β=+0.06, CI: 0.04–0.08, z=6.47, p<0.0001), but not drug effects (48 trials; β= −0.003, CI: −0.02 to +0.01, z= −0.30, p=0.77).

Treatment effects were unrelated to baseline symptom ratings (as the percentage-of-maximum attainable mania scores: 100%=60 for YMRS; 100%=52 for MRS, to avoid confounding by scaling differences) across 47 trials (β=0.43, CI: −0.57 to +0.65, z=0.14, p=0.89). However, higher baseline mania ratings predicted greater improvement with drug (46 trials; β=+0.26, CI: 0.13–0.40, z=3.80, p=0.0002), but not with placebo (36 trials; β=0.02, CI: −0.18 to +0.22, z=0.18, p=0.86).

Publication Bias

As studies with larger than average effects are more likely to be published, it is possible that the studies in a meta-analysis may overestimate the true effect size because they are based on a biased sample of target population of studies. As a first step in exploring any evidence of such bias in the present meta-analysis, the funnel plot of the effect size (Hedges’ g) vs its standard error was plotted, which numerically (not visually) indicated some sort of asymmetry in distribution of the studies (Kendall's tau (τ)=0.19, z=2.02, p=0.04). As a next step for assessment of publication bias we evaluated the possibility that the entire effect is an artifact of bias by calculating Orwin's Fail-safe N value, which was 140, suggesting that a large number of trials with zero effect would need to be added to the analysis to make cumulative effect trivial (defined in this study as Hedges’ g<0.10). We made a concerted effort to include all available completed trials in mania, regardless of publication status; and could only include 38 studies with 56 comparisons (13 being trials with negative findings). Thus, it is very unlikely that we failed to identify such a large of number of studies, and the entire effect is an artifact of bias. For the primary meta-analyses including 56 placebo-controlled comparisons, trim and fill analysis identified and trimmed only one aberrant small study (of tamoxifen with 16 subjects; Zarate et al, 2007), before the funnel plot became symmetric about the adjusted effect size (Hedges’ g) of 0.37 (CI: 0.29–0.45), indicating only a trivial change on the observed overall effect-size (Hedges’ g=0.37, CI: 0.31–0.42). When we considered only the trials for effective agents however, trim and fill analysis did not identify any aberrant studies; and the summary effect remained unchanged at the Hedges’ g of 0.42 (CI: 0.36–0.48). Overall, these considerations indicate that the effect of publication bias in this meta-analysis was negligible.

DISCUSSION

Efficacy of Agents and Groups of Agents

The primary meta-analysis based on 10 800 ITT patients from 38 studies with 56 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparisons of 17 investigated drugs found that 13 agents (76.5%) were more effective than placebo for acute symptoms of mania. These included all eight SGAs tested, as well as haloperidol as the only FGA tested (widely used but never licensed for mania), tamoxifen (a central PKC inhibitor), and two mood-stabilizing anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, valproate), and lithium. Agents that appeared to be most effective compared to placebo (based on effect size as Hedges’ g>0.50) were: tamoxifen (2.32, in two small, single-site trials), risperidone (0.66), carbamazepine (0.61, two trials), haloperidol (0.54), cariprazine (0.51, one trial), whereas eight other agents had smaller effect sizes: olanzapine (Hedges’ g=0.46), ziprasidone (0.42), asenapine (0.40, two trials), quetiapine (0.40), lithium (0.39), paliperidone (0.30), valproate (0.28), and aripiprazole (0.26; Figure 1). To avoid bias we included all available data in all analyses. Pooled effect size estimates for aripiprazole and paliperidone involved trials with various doses of test drugs, only some of which were effective. When only highest doses were considered, the effect size for aripiprazole (at 30 mg/day) increased only slightly, from Hedges’ g of 0.26 to 0.31 (CI: 0.16–0.46 in five trials with 1405 subjects, p<0.0001) and its dose effects were very limited. Pooled effect size for paliperidone for the highest dose (12 mg/day) vs all doses increased substantially, from Hedges’ g of 0.30 to 0.51 (CI: 0.27–0.76 in two trials with 529 subjects, p<0.0001), and its dose effects were correspondingly robust. Four agents: lamotrigine, S-licarbazepine (principal active metabolite of oxcarbazepine, in one comparison with placebo), topiramate, and verapamil were apparently ineffective in mania: (all Hedges’s g=−0.06 to +0.09; Figure 1). Of note proposed mechanism of action of effective and ineffective agents did not appear to account for efficacy. For example, some effective and ineffective anticonvulsant–antimanics shared ability to block sodium channels or to potentiate the inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitter GABA.

Agents found to be more effective than placebo demonstrated moderate absolute differences in responder rates (RDs=0.17), medium overall effect size (Hedges’ g=0.42), and NNT (6; Table 3). Exclusion of two small studies of tamoxifen with large drug–placebo differences did not change these results (RD=0.17, Hedges’ g=0.41, NNT=6). The close similarity of these computed measures of drug-over-placebo efficacy to the meta-analytically pooled efficacy of SGAs in schizophrenia is noteworthy (Leucht et al, 2009).

We also identified 32 direct, head-to-head drug comparisons, but they were limited in the range of drugs studied, and not all were double-blind or placebo controlled (Table 2). Various types of antipsychotic drugs appeared to be somewhat more effective than MSs; and SGAs did not differ appreciably from haloperidol (the only FGA tested; Table 4). Despite compelling evidence of antimanic efficacy for haloperidol (Hedges’ g=0.54), FGAs are no longer commonly used to treat acute mania, owing mainly to their unfavorable risks of short- and long-term adverse effects that need to be balanced against considerable long-term adverse metabolic effects of some SGAs (Baldessarini and Tarazi, 2005). Although relatively few direct comparisons seemed to favor SGAs over MSs for acute mania (Table 4), these groups of drugs showed similar pooled effect sizes when compared with placebo (Table 3). Moreover, all of the trials considered were very short (approximately only 2 weeks, when drop-out rates are considered), raising the possibility that speed-of-clinical action may favor the antipsychotics, especially through their almost immediate nonspecific or sedating actions (Baldessarini and Tarazi, 2005). As full clinical recovery from acute mania typically requires many weeks, the effects of SGAs versus MSs should be followed for longer times (Bowden et al, 2008; Tohen et al, 2008; Vieta et al, 2010b). In the absence of such long term, direct comparisons, one can consider the similar effect sizes of MSs and SGAs, the established neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects of MSs (Chang et al, 2009; Manji et al, 2000), and the long-term adverse metabolic effects of some SGAs (Baldessarini and Tarazi, 2005) in attempting to compare these classes of effective antimanic agents for clinical selection in the treatment of acute mania. Whereas the findings of the trials reviewed above strongly indicate that many candidate antimanic agents are significantly more effective than placebo, their similar effect sizes and overlapping CIs make it hard to conclude that one type is superior to another. Moreover, current clinical practice, driven largely by pressures of time and cost, often use more than one treatment to bring mania under control as quickly as possible—often combinations of MSs (carbamazepine, lithium, valproate), antipsychotics, and potent sedatives, at least temporarily (Baldessarini and Tarazi, 2005; Centorrino et al, 2010). A further question that clinicians may take into account when prescribing antimanic drugs, which goes beyond the scope of this meta-analysis, is their capacity to protect against switch into depression. Thus, the possibility that the most effective antimanic agents might not necessarily be the best to prevent depression may count against their use in clinical practice and might also explain why some combinations are more widely used than others (Vieta et al, 2009).

Factors Associated with Treatment Effects

This large database yielded evidence for smaller drug–placebo contrasts, and greater placebo-associated benefits in trials of acute mania involving larger number of collaborating sites, as well as patient samples. Two small, single-site studies of tamoxifen yielded remarkably large apparent therapeutic effects with particularly small placebo effects (Table 3). Post-hoc meta-regression after exclusion of these two tamoxifen trials confirmed the observed associations between higher number of collaborating study sites and smaller drug–placebo contrasts (46 trials; β= −0.05, CI: −0.009 to −0.002, z= −2.86, p=0.004), as well as greater placebo-induced improvement in mania ratings (36 trials; β=+0.06, CI: 0.03–0.10, z=3.66, p=0.00025). Regarding sample sizes, although the association between larger sample sizes and smaller treatment effects was no longer observed, greater placebo-associated benefit in larger trials of acute mania (36 trials; β=+0.04, CI: 0.02–0.05, z=4.17, p=0.00003) was supported after exclusion of two tamoxifen trials, indicating that small studies are likely to encounter lesser placebo effects. Sterne et al (2001) stated that the effect size may be larger in small studies because of retrieval of a biased sample of the smaller studies, but it is also possible the effect size really is larger in smaller studies for entirely unrelated reasons; such that the small studies may have been performed using patients who were quite ill (therefore more likely to benefit from drugs as indicated in this report; β=+0.26, p=0.0002), or the small studies may have been performed with better (or worse) quality control than the large ones.

Meta-regression modeling found that drug-associated benefit increased with initial symptom severity (based on mania ratings at intake). In a meta-analysis based on individual responses, Fournier et al (2010) reported that drug–placebo differences, and clinical change in symptoms of MDD during treatment with placebo or antidepressants, all tended to increase as initial severity of depression increased. However, in acute bipolar mania initial manic symptom severity did not appear to enhance observed drug–placebo contrasts, but amplified benefit from the drugs selectively. This may relate with the view that more severely ill patients better represent a target phonotype, or that initially high scores have more room for improvement. These observations suggest that the law of initial values (more deviant initial assessments tend to yield greater change with interventions) may well apply to experimental therapeutics, perhaps with different patterns for different disorders (Benjamin, 1963).

Study Limitations

Despite vigorous efforts to gain access to data from all available relevant trials, it is possible that some, especially negative, findings were not accessed. For some treatments, available numbers of trials and subjects were small, and most trials did not provide sufficient data to evaluate effects of treatment exposure time, or of other demographic or clinical factors that might suggest subgroups of particular interest. Also, some subgroup analyses involved particularly a few trials or subjects, or involved substantial inter-study variance (eg, effects of verapamil, or of lithium versus anticonvulsants), and their results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

The present comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of treatments for acute bipolar mania indicates at least moderate effect sizes, with statistical superiority over placebo found with 13/17 drugs, most of which are in common clinical use. In trials of individual drugs vs placebo, efficacy measures (differences in improvement of mania ratings or rates of response (achieving ⩾50% improvement) in 2–3 weeks) and their 95% CIs were similar among most of the effective agents identified, and so do not indicate clear superiority of one agent or drug class over others. Nevertheless, a limited number of direct comparisons indicated that antipsychotic agents (SGAs or haloperidol) may have had somewhat superior apparent efficacy or more rapid action than the group of mood stabilizers tested (carbamazepine, lithium, valproate). Further development of improved antimanic drugs calls for agents with even better efficacy through clinical remission with better short- and long-term tolerability, as well as further testing of relative efficacy of existing compounds in more head-to-head, randomized comparisons.

References

Altman DG (1988). Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ 317: 1309–1312.

American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th edn, text revision. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC.

AstraZeneca (2010). Multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo controlled, phase III study of the efficacy and safety of quetiapine fumarate (Seroquel®) sustained-release as monotherapy in adult patients with acute bipolar mania. Study ID Number: D144CC00004. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00422123 AstraZeneca (Data on file).

Baldessarini RJ, Tarazi FI (2005). Pharmacotherapy of psychosis and mania. In: Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL (eds). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 11th edn. McGraw-Hill Press: New York, pp 461–500.

Benjamin LS (1963). Statistical treatment of the law of initial values (LIV) in autonomic research: a review and recommendation. Psychosom Med 25: 556–566.

Berk M, Ichim L, Brook S (1999). Olanzapine compared to lithium in mania: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 14: 339–343.

Berwaerts J, Xu H, Nuamah I, Lim P, Hough D (2009). Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study of paliperidone ER for acute manic and mixed episodes in bipolar I disorder. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00299715. American Psychiatric Association 162nd Annual Meeting. San Francisco, CA.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis, 1st edn. John Wiley & Sons Ltd: West Sussex, UK.

Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F et al, Depakote Mania Study Group (1994). Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. JAMA 271: 918–924.

Bowden CL, Göğüş A, Grunze H, Häggström L, Rybakowski J, Vieta E (2008). A 12-week, open, randomized trial comparing sodium valproate to lithium in patients with bipolar I disorder suffering from a manic episode. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 23: 254–262.

Bowden CL, Grunze H, Mullen J, Brecher M, Paulsson B, Jones M et al (2005). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety study of quetiapine or lithium as monotherapy for mania in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 66: 111–121.

Bowden CL, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Rubenfaer LM, Wozniak PJ, Collins MA et al, Depakote ER Mania Study Group (2006). Randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of divalproex sodium extended release in the treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychiatry 67: 1501–1510.

Centorrino F, Ventriglio A, Vincenti A, Talamo A, Baldessarini RJ (2010). Changes in medication practices for hospitalized psychiatric patients: 2009 versus 2004. Hum Psychopharmacol 25: 179–186.

Chang YC, Rapoport SI, Rao JS (2009). Chronic administration of mood stabilizers upregulates BDNF and Bcl-2 expression levels in rat frontal cortex. Neurochem Res 34: 536–541.

Der Simonian R, Laird N (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7: 177–188.

Duval S, Tweedie's R (2000). Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based methof of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56: 455–463.

El Mallakh RS, Vieta E, Rollin L, Marcus R, Carson WH, McQuade R (2010). A comparison of two fixed doses of aripiprazole with placebo in acutely relapsed, hospitalized patients with bipolar disorder I (manic or mixed) in subpopulations. Study ID Number: CN138–007. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 20: 776–783.

Emilien G, Maloteaux JM, Seghers A, Charles G (1996). Lithium compared to valproic acid and carbamazepine in the treatment of mania: a statistical meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 6: 245–252.

Endicott J, Spitzer RL (1978). A diagnostic interview: the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 35: 837–844.

Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC et al (2010). Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: A patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA 303: 47–53.

Freeman TW, Clothier JL, Pazzaglia P, Lesem MD, Swann AC (1992). A double-blind comparison of valproate and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 149: 108–111.

Goldsmith DR, Wagstaff AJ, Ibbotson T, Perry CM (2003). Lamotrigine: a review of its use in bipolar disorder. Drugs 63: 2029–2050.

Hirschfeld RM, Bowden CL, Vigna NV, Wozniak P, Collins M (2010). A randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of divalproex sodium extended release in the acute treatment of mania. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00060905. J Clin Psychiatry 71: 426–432.

Hirschfeld RM, Keck Jr PE, Kramer M, Karcher K, Canuso C, Eerdekens M et al (2004). Rapid antimanic effect of risperidone monotherapy: 3-week multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 161: 1057–1065.

Ichim L, Berk M, Brook S (2000). Lamotrigine compared with lithium in mania: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Ann Clin Psychiatry 12: 5–10.

Janicak PG, Sharma RP, Pandey G, Davis JM (1998). Verapamil for the treatment of acute mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 155: 972–973.

Kakkar AK, Rehan HS, Unni KES, Gupta NK, Chopra D, Kataria D (2009). Comparative efficacy and safety of oxcarbazepine versus divalproex sodium in the treatment of acute mania: a pilot study. Eur Psychiatry 24: 178–182.

Katagiri H, Takita Y, Tohen M, Takahashi M (2010). Efficacy and safety of olanzapine in the treatment of Japanese patients with manic or mixed episode of bipolar I disorder: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel, placebo- and haloperidol-controlled study. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00129220. International College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 27th Annual Congress Hong Kong, China.

Keck Jr PE, Marcus R, Tourkodimitris S, Ali M, Liebeskind A, Saha A et al, Aripiprazole Study Group (2003a). A placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in patients with acute bipolar mania. Am J Psychiatry 160: 1651–1658.

Keck PE, Orsulak PJ, Cutler AJ, Sanchez R, Torbeyns A, Marcus RN et al, CN138–135 Study Group (2009). Aripiprazole monotherapy in the treatment of acute bipolar I mania: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and lithium-controlled study. J Affect Disord 112: 36–49.

Keck Jr PE, Versiani M, Potkin S, West SA, Giller E, Ice K, Ziprasidone in Mania Study Group (2003b). Ziprasidone in the treatment of acute bipolar mania: a three-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry 160: 741–748.

Khanna S, Vieta E, Lyons B, Grossman F, Eerdekens M, Kramer M (2005). Risperidone in the treatment of acute mania: double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 187: 229–234.

Knesevich MA, Wang O, Papadakis K, Korotzer A, Bose A, Laszlovszky I (2009). The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00488618. American Psychiatric Association, 162nd Annual Meeting. San Francisco, CA.

Kushner SF, Khan A, Lane R, Olson WH (2006). Topiramate monotherapy in the management of acute mania: results of four double-blind placebo-controlled trials. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00037674; NCT00240721; NCT00035230. Bipolar Disord 8: 15–27.

Leucht S, Arbter D, Engel RR, Kissling W, Davis JM (2009). How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry 14: 429–447.

Li H, Ma C, Wang G, Zhu X, Peng M, Gu N (2008). Response and remission rates in Chinese patients with bipolar mania treated for 4 weeks with either quetiapine or lithium: a randomized and double-blind study. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00448578. Curr Med Res Opin 24: 1–10.

Manji HK, Moore GJ, Chen G (2000). Clinical and preclinical evidence for the neurotrophic effects of mood stabilizers: implications for the pathophysiology and treatment of manic-depressive illness. Biol Psychiatry 48: 740–754.

McElroy SL, Keck PE, Stanton SP, Tugrul KC, Bennett JA, Strakowski SM (1996). A randomized comparison of divalproex oral loading versus haloperidol in the initial treatment of acute psychotic mania. J Clin Psychiatry 57: 142–146.

McIntyre RS, Brecher M, Paulsson B, Huizar K, Mullen J (2005). Quetiapine or haloperidol as monotherapy for bipolar mania: 12-week, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15: 573–585.

McIntyre RS, Cohen M, Zhao J, Alphs L, Macek TA, Panagides J (2009a). Asenapine versus olanzapine in acute mania: a double-blind extension study. Bipolar Disord 11: 815–826.

McIntyre RS, Cohen M, Zhao J, Alphs L, Macek TA, Panagides J (2009b). A 3-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of asenapine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar mania and mixed states. Bipolar Disord 11: 673–686.

Moncrieff J, Kirsch I (2005). Efficacy of antidepressants in adults. BMJ 331: 155–157.

Niufan G, Tohen M, Qiuqing A, Fude Y, Pope E, McElroy H et al (2008). Olanzapine versus lithium in the acute treatment of bipolar mania: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00485680. J Affect Disord 105: 101–108. (Originally published as e-pub ahead of print May 24, 2007).

Novartis Clinical Trial Results Database (2007). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study to evaluate efficacy and tolerability of licabazepine 1000–2000 mg/d in the treatment of manic episodes of bipolar I disorder over 3 weeks. Study ID Number: CLIC477D2301. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00099229. Novartis (Data on file).

Orwin RG (1983). A fail-safe N for effect-size in meta-analysis. J Ed Stat 8: 157–159.

Perlis RH, Baker RW, Zarate Jr CA, Brown EB, Schuh LM, Jamal HH et al (2006a). Olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of manic or mixed States in bipolar I disorder: a randomized, double-blind trial. J Clin Psychiatry 67: 1747–1753.

Perlis RH, Welge JA, Vornik LA, Hirschfeld RM, Keck Jr PE (2006b). Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of mania: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 67: 509–516.

Pope Jr HG, McElroy SL, Keck Jr PE, Hudson JI (1991). Valproate in the treatment of acute mania. A placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48: 62–68.

Potkin SG, Keck Jr PE, Segal S, Ice K, English P (2005). Ziprasidone in acute bipolar mania: a 21-day randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled replication trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 25: 301–310.

Sachs G, Sanchez R, Marcus R, Stock E, McQuade R, Carson W et al, Aripiprazole Study Group (2006). Aripiprazole in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder: a 3-week placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol 20: 536–546.

Sanofi-Aventis (2007). A twelve-week, open, randomized trial comparing valproate to lithium in Bipolar I patients suffering from a manic episode. Study ID Numbers: R_8740. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00264173. Sanofi-C (Data on file).

Scherk H, Pajonk FG, Leucht S Second-generation antipsychotic agents in the treatment of acute mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2007 4: 442–455.

Segal J, Berk M, Brook S (1998). Risperidone compared with both lithium and haloperidol in mania: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Clin Neuropharmacol 21: 176–180.

Small JG, Klapper MH, Milstein V, Kellams JJ, Miller MJ, Marhenke JD et al (1991). Carbamazepine compared with lithium in the treatment of mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48: 915–921.

Smith LA, Cornelius V, Warnock A, Tacchi MJ, Taylor D (2007). Pharmacological interventions for acute bipolar mania: systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord 9: 551–560.

Smulevich AB, Khanna S, Eerdekens M, Karcher K, Kramer M, Grossman F (2005). Acute and continuation risperidone monotherapy in bipolar mania: a 3-week placebo-controlled trial followed by a 9-week double-blind trial of risperidone and haloperidol. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15: 75–84.

Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E (1978). Research diagnostic criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 35: 773–882.

Sterne JAC, Egger M (2001). Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: Guidelines on choice of axis. J Clinical Epidemiology 54: 1046–1055.

Sterne JAC, Egger M, Smith GD (2001). Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ 323: 101–105.

Tohen M, Baker RW, Altshuler LL, Zarate CA, Suppes T, Ketter TA et al (2002). Olanzapine versus divalproex in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 159: 1011–1017.

Tohen M, Goldberg JF, Gonzalez-Pinto Arrillaga AM, Azorin JM, Vieta E, Hardy-Bayle MC et al (2003). A 12-week, double-blind comparison of olanzapine vs haloperidol in the treatment of acute mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60: 1218–1226.

Tohen M, Jacobs TG, Grundy SL, McElroy SL, Banov MC, Janicak PG et al, Olanzipine HGGW Study Group (2000). Efficacy of olanzapine in acute bipolar mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57: 841–849.

Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KN, Daniel DG et al, Olanzapine HGEH Study Group (1999). Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 156: 702–709.

Tohen M, Vieta E, Goodwin G, Sun B, Amsterdam J, Banov M et al (2008). Olanzapine versus divalproex versus placebo in the treatment of mild to moderate mania: randomized, 12-week, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry 69: 1776–1789.

Tohen M, Zhang F, Taylor CC, Burns P, Zarate C, Sanger T et al (2001). A meta-analysis of the use of typical antipsychotic agents in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 65: 85–93.

Vieta E, Angst J, Reed C, Bertsch J, Haro JM, EMBLEM advisory board (2009). Predictors of switching from mania to depression in a large observational study across Europe (EMBLEM). J Affect Disord 118: 118–123.

Vieta E, Bourin M, Sanchez R, Marcus R, Stock E, McQuade R et al, Aripoprazole Study Group (2005). Effectiveness of aripiprazole v. haloperidol in acute bipolar mania: double-blind, randomised, comparative 12-week trial. Br J Psychiatry 187: 235–242.

Vieta E, Cruz N (2008). Increasing rates of placebo response over time in mania studies. J Clin Psychiatry 69: 681–682.

Vieta E, Nuamah IF, Lim P, Yuen EC, Palumbo JM, Hough DW et al (2010a). A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled study of paliperidone extended release for the treatment of acute manic and mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00309699. Bipolar Disord 12: 230–243.

Vieta E, Ramey T, Keller D, English PA, Loebel AD, Miceli J (2010b). Ziprasidone in the treatment of acute mania: 12- week placebo-controlled, haloperidol-referenced study. J Psychopharmacol 24: 547–558. (Originally published as e-pub ahead of print December 12, 2008).

Weisler RH, Kalali AH, Ketter TA, SPD417 Study Group (2004). A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of extended-release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy for bipolar disorder patients with manic or mixed episodes. J Clin Psychiatry 65: 478–484.

Weisler RH, Keck Jr PE, Swann AC, Cutler AJ, Ketter TA, Kalali AH, SPD417 Study Group (2005). Extended-release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy for acute mania in bipolar disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 66: 323–330.

Whitley E, Ball J (2002). Statistics review 5: Comparison of means. Crit Care 6: 424–428.

Yildiz A, Guleryuz S, Ankerst DP, Ongür D, Renshaw PF (2008). Protein kinase C inhibition in the treatment of mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tamoxifen. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65: 255–263.

Yildiz A, Vieta E, Tohen M, Baldessarini RJ (2010). Placebo-related response in clinical trials for bipolar mania: what is driving this phenomenon and what can be done to minimize it? European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 23rd Annual Congress Breaking News Symposia: Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Young AH, Oren DA, Lowy A, McQuade RD, Marcus RN, Carson WH et al (2009). Aripiprazole monotherapy in acute mania: a 12-week, randomized placebo- and haloperidol-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 194: 40–48.

Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA (1978). A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 133: 429–435.

Zajecka JM, Weisler R, Sachs G, Swann AC, Wozniak P, Sommerville KW (2002). A comparison of the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of divalproex sodium and olanzapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 63: 1148–1155.

Zarate Jr CA, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Quiroz J, Jolkovsky L, Luckenbaugh DA et al (2007). Efficacy of a protein kinase C inhibitor (tamoxifen) in the treatment of acute mania: a pilot study. Bipolar Disord 9: 561–570.

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by educational grants from the Actavis-Turkey (to AY); by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PR 2007–0358), Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM) (to EV); by a grant from the Bruce J Anderson Foundation and the McLean Private Donors’ Research Fund (to RJB). Sponsors had no influence on the conduct, analysis, or reporting of this study. We thank Seren Özer for contributing to study identification and data extraction. Unpublished information was generously provided by Dr Charles Bowden, Dr Paul Keck Jr, Dr Roger McIntyre, Dr Harrison G Pope Jr, Dr Steven Potkin, Dr Richard Weisler, and their colleagues, as well as representatives of Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, and Pfizer Corporations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr Yildiz has received research grants from and/or served as a consultant or speaker for Actavis, Ali Raif, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Servier Corporations. Dr Vieta has served as a consultant or speaker for Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forest Research Institute, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Jazz, Lundbeck, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Servier Corporations. Dr Leucht has received research grants from and/or served as a consultant or speaker for Actelion, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Essex, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis Corporations. Dr Baldessarini has no current sources of potential conflicts of interest to report, and neither he nor any family member has equity relationships with pharmaceutical or biomedical corporations.

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yildiz, A., Vieta, E., Leucht, S. et al. Efficacy of Antimanic Treatments: Meta-analysis of Randomized, Controlled Trials. Neuropsychopharmacol 36, 375–389 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2010.192

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2010.192

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Efficacy and safety of scopolamine compared to placebo in individuals with bipolar disorder who are experiencing a depressive episode (SCOPE-BD): study protocol for a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial

Trials (2022)

-

Normalization of impaired emotion inhibition in bipolar disorder mediated by cholinergic neurotransmission in the cingulate cortex

Neuropsychopharmacology (2022)

-

Combining schizophrenia and depression polygenic risk scores improves the genetic prediction of lithium response in bipolar disorder patients

Translational Psychiatry (2021)

-

HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQB1 genetic diversity modulates response to lithium in bipolar affective disorders

Scientific Reports (2021)