Abstract

Maternal deprivation in rats specifically leads to a vulnerability to opiate dependence. However, the impact of cannabis exposure during adolescence on this opiate vulnerability has not been investigated. Chronic dronabinol (natural delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol, THC) exposure during postnatal days 35–49 was made in maternal deprived (D) or non-deprived (animal facility rearing, AFR) rats. The effects of dronabinol exposure were studied after 2 weeks of washout on the rewarding effects of morphine measured in the place preference and oral self-administration tests. The preproenkephalin (PPE) mRNA levels and the relative density and functionality of CB1, and μ-opioid receptors were quantified in the striatum and the mesencephalon. Chronic dronabinol exposure in AFR rats induced an increase in sensitivity to morphine conditioning in the place preference paradigm together with a decrease of PPE mRNA levels in the nucleus accumbens and the caudate–putamen nucleus, without any modification for preference to oral morphine consumption. In contrast, dronabinol treatment on D-rats normalized PPE decrease in the striatum, morphine consumption, and suppressed sensitivity to morphine conditioning. CB1 and μ-opioid receptor density and functionality were not changed in the striatum and mesencephalon of all groups of rats. These results indicate THC potency to act as a homeostatic modifier that would worsen the reward effects of morphine on naive animals, but ameliorate the deficits in maternally D-rats. These findings point to the self-medication use of cannabis in subgroups of individuals subjected to adverse postnatal environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

It has been well established that endogenous cannabinoid and opioid systems of the brain functionally interact to mediate the rewarding and reinforcing effects of cannabinoids and opioids, but their specific role is actually much debated. In particular, controversial results have been reported regarding their possible additive effects and the fact that cannabis intake facilitates progression to consumption of opioids (for review, see in Gardner and Vorel, 1998). A wide distribution of opioid and cannabinoid receptors exists in the different brain structures of the reward circuitry (Herkenham et al, 1991; Mansour et al, 1995; Mason et al, 1999). In the striatum, CB1 receptors are synthesized in striatopallidal neurons that contain GABA and enkephalins (Hohmann and Herkenham, 2000, Rodriguez et al, 2001). CB1 and μ-opioid receptors (MORs) are also present within some of the same, as well as synaptically linked neurons in the striatum (Pickel et al, 2004). Opioid and cannabinoid receptors are members of the G-protein-coupled family of receptors (Matsuda et al, 1990; Kieffer, 1999), and they modulate similar transduction systems, including the cAMP-protein kinase A cascade (Howlett, 1995). Converging research findings have shown the existence of a functional cross-interaction between opioid and cannabinoid receptors in motor behavior and reward (Ledent et al, 1999; Navarro et al, 2001; Tanda and Goldberg, 2003). Experimental studies show that cannabinoid pre-exposure enhances opiate-induced locomotor activity, behavioral sensitization to morphine (Rubino et al, 2000; Cadoni et al, 2001; Lamarque et al, 2001; Cadoni et al, 2001; Norwood et al, 2003; Singh et al, 2005), and conditioned morphine place preference (CPP) in rodents (Manzanedo et al, 2004). Contradictory data have also been published showing tolerance to the rewarding effects of morphine in chronically treated mice with delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), one of the main psychoactive compounds of marijuana (Valverde et al, 2001; Jardinaud et al, 2006). A reduction of heroin-induced Fos immunoreactivity in the brain structures involved in the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse has been found after chronic THC treatment, suggesting that pre-exposure to THC may lead to permanent changes in the opioid system (Singh et al, 2005). Most of the studies were performed after chronic cannabinoid treatment in adult animals and very little data were reported after chronic cannabinoid exposure during adolescence, which is an important neurodevelopmental period. Adolescence may be a stage of particular vulnerability to the effects of THC, as cannabinoid receptors have been shown to mature slowly with maximal levels during adolescence and may undergo post-adolescent pruning (Rodriguez de Fonseca et al, 1993; Belue et al, 1995). Rat adolescent exposure to WIN55212.2 has been shown to induce tolerance to the cannabinoid agonist and cross-tolerance to other drugs such as morphine in adult midbrain dopamine neurons (Pistis et al, 2004), whereas an increase of heroin intake (Ellgren et al, 2007) and heroin-induced CPP (Singh et al, 2006) has been described after THC pre-exposure of rat during adolescence and of heroin-induced CPP after THC postnatal exposure (Biscaia et al, 2008). It has been speculated that these apparently opposite results could be because of the different biochemical properties of the CB1 compounds used, and the period of abstinence before testing. Another approach to reveal the influence of cannabis on opiate reward is to examine the effects of cannabis on animals known to present a vulnerability to opiate dependence. We have shown that deprivation of infant-mother-litter (maternal deprivation) relationship leads to a hypersensitivity to the rewarding effect of morphine, to morphine dependence, and to modifications in the balance of opioidergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission (Vazquez et al, 2005, 2007). Enduring neurobiological changes have been described with basal hypoactivity of the enkephalinergic system in deprived (D) rats, which could explain their sensitivity to opiate dependence (Vazquez et al, 2005). Maternal deprivation specifically enhances vulnerability to opiate dependence (Vazquez et al, 2006), representing a highly valuable model to study the hypothesis that cannabis intake during adolescence may enhance or not the addictive effect of opiates and facilitate or not the progression to their consumption.

Maternal deprivation model was used in this study to evaluate the impact of chronic and irregular exposure with dronabinol (natural THC) during adolescence on the rewarding effects of morphine and on the enkephalinergic and cannabinoid systems in the striatum and the mesencephalon, regions of the brain involved in opiate reward (Shippenberg et al, 1993; van Ree et al, 2000) in D and non-deprived (animal facility rearing, AFR) rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Five series of 20 Long–Evans rats (Janvier, Le Genest St Isle, France) on day 14 of gestation were used. The dams gave birth 1 week after inclusion. Litters were housed in plastic cages in a well-ventilated, temperature controlled (22±1°C) environment on a 12 h light–dark cycle (lights on from 0800 hours to 2000 hours). Dams received rat chow and water ad libitum. The experimental procedure and care of the animals were in accordance with local committee guidelines and the European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC).

Drugs

Dronabinol (97–98% natural stereo isomer of THC) purchased from THC Pharm (Frankfurt, Germany) was dissolved in ethanol, cremophore, and sterile water (1 : 1 : 18). Morphine HCl was purchased from Francopia (France) and dissolved in 0.9% saline for the place preference experiments. Dronabinol, morphine, and vehicle were i.p. administered in a volume of 1 ml/kg. Morphine (25 mg/l) was dissolved in tap water for the oral self-administration test.

Maternal Deprivation Procedure

Maternal deprivation was performed as described previously (Vazquez et al, 2005). On postnatal day 1, litters were cross-fostered and culled to eight male pups. Neonates belonging to the maternal deprivation group were individually placed in temperature (30–34°C) and humidity-controlled cages divided into compartments. Pups were isolated for 3 h daily from days 1–14 (1300–1600 hours). D pups received no other handling except that required to change the bedding in their cages once a week. Rat pups not subjected to maternal deprivation (AFR) remained with their mothers during this period and received no specific handling other than changing the bedding in their cages once a week.

From days 15–22, all pups remained with their mothers. On day 22, pups were weaned from their mothers and housed in groups of 3–4. One or two rats from each litter within the group were used in individual experiments to avoid any litter effect.

Chronic Dronabinol Treatment

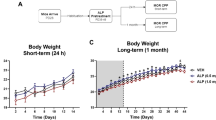

The rats were injected with dronabinol (5 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle during postnatal days 35–48 to extend beyond the prototypic adolescent period (Andersen, 2003). To mimic the intermittent and escalating use seen in teenagers, the administration was performed with days of abstention and increased doses (Figure 1). Behavioral experiments were processed between 2 and 4 weeks after the last injection.

Experimental procedure for chronic dronabinol exposure. Maternal deprivation started one day after birth (D1) 3 h daily for 14 days. Weaning occurred at days 21–22. The chronic i.p. injection of dronabinol started at day 35. The administration was performed with days of abstention and increased doses (5 or 10 mg/kg) until D48. Behavioral studies were performed 2 or 4 weeks after the last dronabinol injection.

Place Preference Paradigm

The CPP was performed using a nonbiased procedure as described previously (Vazquez et al, 2005). During the conditioning phase, rats were pretreated with morphine 1, 2, or 5 mg/kg i.p. on days 1, 3, and 5, and with saline (1 ml/kg) on days 2, 4, and 6 immediately before being confined in the conditioning compartment for 25 min. Control rats received saline every day. The preference score is the difference between the post-conditioning and pre-conditioning times spent in the compartment associated with drug.

Morphine Oral Self-Administration

The measurement of morphine solution consumption was performed during 12 weeks using a two-bottle choice paradigm as described (Vazquez et al, 2005, 2006). The rats were first trained to consume water for 5 days to habituate the rats to the free choice. One of the bottles of water was then replaced by a bottle of morphine solution (25 mg/l) during 12 weeks. No sucrose was added to the morphine solution. The consumption in ml was measured twice a week.

Tissue Section Preparation

At 2 weeks after CPP experiments, five rats from the vehicle and dronabinol groups were killed by decapitation and their brains were frozen in isopentane at −20°C and then stored at –80°C. Coronal sections (10 μm) were cut in a cryostat (Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany) at the level of the striatum and the mesencephalon (four adjacent sections per slide) according to the frontal plan of the stereotaxis atlas of Paxinos and Watson 1997). Slices were thaw-mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Menzel-Glass, Braunschweig, Germany).

In Situ Hybridization Experiment

The preproenkephalin (PPE) probe was a synthetic DNA 30-mer complementary to nucleotides 978–1007 of the rat PPE mRNA. No homology (>72%) was found to any gene presently cloned (EMBL version 35: 119 518 sequence) in mammals. The probe was labeled at the 3′-terminal with [35S]dATP (Amersham Biosciences, Les Ulis, France) by terminal deoxynucleotide transferase to a specific activity of 5 × 108 dpm/μg. The slices were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS. Sections were then covered with 140 μl of a hybridization medium (Helios Bioscience, Créteil, France) containing the labeled oligonucleotide and incubated overnight at 42°C. The slices were rinsed with an SDS buffer at 55°C. Tissue sections and slice-mounted [14C] microscale standards were exposed to a BAS-SR Fujifilm Imaging Plate (Fuji Film Photo Co., Tokyo, Japan) for 5 days.

Autoradiographical Experiments

For the MOR receptors, labeling was performed as described in Vazquez et al, (2005). Slices were incubated in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 3.4 nM [3H]-DAMGO (Amersham Biosciences) for 1 h. Non-specific binding was determined with 10 mM naloxone (Sigma, Evry, France). Tissue sections and slice-mounted [3H] microscale standards were exposed to BAS-TR Fuji Imaging Plate for 15 days.

For the CB1 receptors, [3H](−)-CP-55 940 binding autoradiography was performed as described previously in Herkenham et al, 1991. Slices were incubated at 37°C for 2 h 30 min in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 5% BSA and 10 nM of [3H]CP-55 940 (Amersham). Non-specific binding was determined with 10 μM unlabeled CP-55 940. Tissue sections and slice-mounted [3H] microscale standards were exposed to BAS-TR Fuji Imaging screens for 7 days.

Agonist-Stimulated [35S]GTPγS Autoradiography

Brain sections were rinsed in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 with 5% BSA for the WIN55212–2 incubation, at 25°C for 10 min, pretreated for 15 min with 2 mM of GDP (McKinney et al, 2008). Sections were incubated in buffer (0.04 nM [35S]GTPγS (Amersham Biosciences), 2 mM GDP, 100 mM DTT, and 3 μM DAMGO or 10 μM WIN55212–2) at 25°C for 2 h. Basal activity was assessed by incubation without ligand. Tissue sections and slice-mounted [14C] microscale standards were exposed to a BAS-SR Fujifilm Imaging Plate for 24 h.

Quantification of Relative Density of PPE, MOR, CB1 Receptors, and G-Protein Coupling

Standard radioactive microscales (GE Healthcare Europe GMBH) were exposed on each autoradiographic film to ensure that densities of the labeling were in linear range. After autoradiogram scanning, densities were measured using MCID analysis software (Imaging Research, St Catharines, ON, Canada). Structures were identified with reference to the brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson 1997. The relative density (nCi/mg) was quantified in both hemispheres after subtraction of non-specific labeling. The values obtained in both hemispheres were then averaged. For each region, the relative density of four sections per slide were meant to give one value per animal. The mean of relative density±SEM was calculated in AFR and D rats treated or not with dronabinol.

Statistical Analysis

A non-parametric statistical test was used to analyze the biochemical and CPP experiments because the results did not fit with a Gaussian repartition (StatEL, ad Science, France). The results of autoradiographical, in situ hybridization, and place preference experiments were analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis test and post hoc analysis was performed with Mann–Whitney test. The oral self-administration behavior was analyzed using two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA: between-subject for deprivation and treatment and within subject for time) followed by Newman–Keuls for multiple comparisons. All data were analyzed with Statview software (SAS, Cary, NC, USA) for Macintosh. The level chosen for statistical significance was 5%.

RESULTS

Place Preference Paradigm

The AFR rats only showed a preference for the associated compartment at the dose of 5 mg/kg of morphine (p<0.05) as expected from the previous study (Vazquez et al, 2005). AFR-dronabinol rats showed a place preference at 1, 2, and 5 mg/kg of morphine (p<0.05) indicating that AFR-dronabinol rats were hypersensitive to the reward effect of morphine. D rats showed a preference for the associated compartment at the three doses of morphine (p<0.01) as expected (Vazquez et al, 2005), whereas D-dronabinol rats did not, indicating that D-dronabinol rats were no longer sensitive to the reward effect of morphine (Figure 2). (Kruskal–Wallis test: (H=37.67, p<0.001)).

Effects of morphine (1, 2, and 5 mg/kg i.p.) on the expression of the place preference paradigm in non-deprived (AFR, n=37), non-deprived dronabinol (AFR-Dr, n=40), deprived (D, n=38), deprived dronabinol (D-Dr, n=47) rats. Rats were tested at 2.5–3 months of age. The results are expressed as a score, calculated as the difference between the post-conditioning and pre-conditioning times spent in the compartment associated with morphine. Error bars represent SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs the respective saline group.

Measurement of Morphine Solution Consumption

There was no difference in total fluid intake between the four groups (data not shown).

A significant difference was observed in morphine consumption between AFR and D rats. ANOVA: deprivation: (F(1,19)=9.89, p<0.01), treatment: (F(1,19)=6.82, p<0.01), week: (F(11,209)=5.37, p<0.0001), deprivation × treatment: (F(1,209)=5.00, p<0.05), deprivation × week: (F(11,209)=1.02, NS), deprivation × treatment × week: (F(11,209)=4.60, p<0.0001). The four groups of rats started with a consumption of around 0.4 mg/kg/24 h. Only D rats progressively increased their morphine consumption to 1.5 mg/kg/24 h. Morphine consumption in D-dronabinol and AFR-dronabinol rats was not significantly different when compared with the AFR group (Figure 3b).

Oral morphine (25 mg/l) self-administration behavior using the two-bottle-choice paradigm in non-deprived (AFR, n=6), non-deprived dronabinol (AFR-Dr, n=5), deprived (D, n=6), deprived dronabinol (D-Dr, n=6) rats for 12 weeks. (a) Morphine preference. (b) Morphine solution consumption. The results are expressed as the mean±SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs AFR, AFR-dronabinol, and D-dronabinol groups.

A significant difference was found in morphine preference between AFR and D rats. ANOVA: deprivation: (F(1,19)=10.81, p<0.01), treatment: (F(1,19)=8.38, p<0.01), week: (F(11,209)=16.19, p<0.0001, deprivation × treatment: (F(1,209)=4.46, p<0.05), week × deprivation: (F(11,209)=2.40, p<0.01), week × treatment: (F(11,209)=2.38, p<0.01), week × treatment × deprivation: (F(11,209)=2.64, p<0.01). The four groups of rats started with a preference of about 30%, indicating an obvious aversion for morphine solution. Only D rats progressively increased their preference for morphine to 65%. Morphine preference in D-dronabinol and AFR-dronabinol rats was not significantly different when compared with the AFR group (Figure 3a).

Preproenkephalin mRNA Expression in the Brain

A significant decrease in PPE mRNA levels was observed in the cone (or medial shell) of the nucleus accumbens (N.Acc.) and in the caudate–putamen nucleus (CPu) of the AFR-dronabinol group compared with AFR rats. A significant decrease in PPE mRNA levels was observed in the cone and the core of the N.Acc and in the CPu of D rats compared with AFR rats. A significant increase in PPE mRNA levels was observed in the core of the N.Acc. and in the CPu of D-dronabinol rats compared with D animals but not when compared with the AFR control group (Figure 4e,f). Kruskal–Wallis test: CPu (H=13.13, p<0.01), core (H=9.79, p<0.01), cone (H=7.67, p<0.05) of the N.Acc.

CB1 and MOR opioid receptor density and functionality in the nucleus accumbens (N.Acc.), the caudate–putamen nucleus (CPu), the substantia nigra (SN), and the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of non-deprived (AFR) and deprived (D) rats treated or not with chronic dronabinol (Dr) exposure. (a) CB1 binding: [3H]CP-55940 (nCi/mg), (b) WIN552122 stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding (nCi/mg), (c) MOR opioid binding: [3H]DAMGO (nCi/mg), (d) DAMGO stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding (nCi/mg) (n=4–6 for each group). (e) PPE mRNA hybridization signals (nCi/mg) in the cone, core of the N.Acc., and in the CPu of AFR (n=4), AFR-Dr (n=5), D (n=4), and D-Dr (n=4) rats. **p<0.01 vs respective control, °°p<0.01 vs AFR saline group. (f) Representative autoradiograms of the distribution of PPE mRNA levels in the CPu and in the N.Acc. of AFR and D rats treated or not with Dr.

CB1 Receptor Density and Function

No significant change between the four groups in CB1 receptor binding was observed in the CPu (H=5.1), the N.Acc. (H=0.9), the SN (H=1.4), and in WIN55212–2 stimulated ([35S]GTPγS) binding in the CPu (H=4.2), the N.Acc. (H=1.2), the SN (H=3.0), and the VTA (H=0.4) (Figure 4a,b).

MOR Receptor Density and Function

No significant change between the four groups in MOR receptor binding was observed in the CPu (H=2.3), the N.Acc. (H=0.5), the SN (H=0.2), and in DAMGO-stimulated ([35S]GTPγS) binding in the CPu (H=2.3), the N.Acc.(H=3.2), the SN (H=1.6), and the VTA (H=0.9), (Figure 4c,d).

DISCUSSION

This study showed that repeated and irregular exposure to escalating doses of THC during adolescence led to changes in the enkephalinergic system of adult rats. This is revealed by modifications of the sensitivity to the rewarding and reinforcing effects of morphine and in the PPE mRNA levels. However, opposite results were found after maternal deprivation.

The AFR-dronabinol rats showed a potentiation to morphine conditioning compared with control animals, but their morphine consumption and preference were similar to the one of AFR control rats, as expected from our previous data with control animals (Vazquez et al, 2005). An analysis of morphine intake across 12 weeks showed that both groups initially presented an avoidance for morphine solution (30%) compared with water. This is in agreement with other studies in which sucrose was not added to the solution and is substantiated by the aversive taste of morphine (Wolffgramm and Heyne 1995). This indicates that dronabinol treatment did not affect the ability to sense the aversive taste of morphine. There is not always a concordance in the ability of opioids to produce CPP and engender self-administration in rats (for review, see Bardo and Bevins, 2000; Vazquez et al, 2006). Context-drug associative learning (CPP) is likely fundamentally distinct from the acquisition of a drug-reward or -reinforced response at least in part because they are subserved by distinct neuropharmacological circuitry (for review, see Bardo and Bevins, 2000). The discordance observed in this study may be in favor of a specific molecular impact of chronic THC exposure during adolescence in the brain structures, which have a role in mediating a context-opioid associative learning in our experimental conditions. We studied the state of the endocannabinoid and enkephalinergic neurotransmissions at the transcriptional and translational levels. A significant decrease of PPE mRNA expression in the N.Acc. and in the CPu of AFR-dronabinol rats was observed without change in the density of CB1 and MOR receptors neither in WIN55212–2- or DAMGO-mediated protein G activation in the striatum nor in the mesencephalon of AFR-dronabinol animals. Repeated THC treatment has been shown to produce receptor downregulation and desensitization of CB1 receptor-mediated G protein activation with less cannabinoid receptor adaptation in striatal circuits (for review, see Sim-Selley, 2003; Romero et al, 1998; McKinney et al, 2008). The most simple explanation to the lack of change in CB1 receptor levels and WIN55212–2 mediated protein G activation observed in this study (see also Ellgren et al, 2007) could be the long period of THC abstinence in contrast to those cited above in which the studies were performed about 24 h after the last THC injection.

The relative decrease of PPE mRNA levels in the striatum of AFR-dronabinol rats compared with AFR-vehicle rats suggests a persistent disturbance of the enkephalinergic reward system in agreement with the increase in PPE mNRA level observed in CB1 knockout mice (Steiner et al, 1999). A similar relationship between a decrease in PPE mRNAs and the development of morphine-inducing reward hypersensibility was described (Corchero et al, 1998; Vazquez et al, 2005). However, pretreatment with THC at the adolescent period has been shown to enhance i.v. heroin self-administration, to increase PPE mRNA expression in the N.Acc. and MOR receptor GTP-coupling in the mesencephalon, which could reflect an allostatic compensatory response during the drug-free period to reduce transcription during the active exposure to THC (Ellgren et al, 2007). These discrepancies could be because of differences in the protocol of self-administration (i.v. heroin self-administration), the experimental procedure of THC treatment (drug was given once every third day from PNDs 28–49), the dose (1.5 mg/kg), and the time of THC washout (1 week).

D-control rats showed a hypersensitivity to the rewarding effect of morphine and a strong increase in oral morphine self-administration behavior and preference associated with a decrease in PPE mRNA level in the striatum compared with AFR control rats, as expected from our previous data (Vazquez et al, 2005). In contrast to the relative stable morphine consumption in AFR rats and despite the aversive taste of the morphine (initial preference 30%), D rats developed a preference for morphine. This evolutive pattern of morphine daily consumption refutes a possibility that maternal deprivation could change the biological circuitry of taste sensing in D rats rendering morphine taste less aversive.

In contrast to AFR-dronabinol rats, adult D-dronabinol animals showed a tolerance to morphine conditioning in CPP, a suppression of escalation behavior in oral morphine self-administration test. D control and D-dronabinol rats initially presented an avoidance for morphine solution compared with water indicating that maternal deprivation and dronabinol treatment did not affect the ability to sense the aversive taste of morphine. Adolescent chronic WIN55212–2 exposure has been shown to induce a long-lasting tolerance to the effect of morphine on the activity of dopamine neurons in the VTA (Pistis et al, 2004). In addition, adolescent chronic THC exposure blocked synaptic plasticity in the N.Acc. and reduces the sensitivity of GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses to both THC and opioids (Hoffman et al, 2003). The lack of morphine rewarding effect in D-dronabinol rats does not seem to be because of an alteration of CB1 and MOR opioid receptors, as no modification was observed in the CB1 and MOR receptor density and functionality in the striatum and the mesencephalon of D-dronabinol animals. Interestingly, dronabinol exposure in D rats led to an increase in PPE mRNA expression in the N.Acc. and in the CPu. As the PPE mRNA levels returned to the AFR control value, this may not totally explain the morphine tolerance occurrence. Other neurotransmitter systems and molecular mechanisms such as downstream effectors in the intracellular cascade common to CB1 and MOR receptors, internalization, or heterodimerization mechanisms could be involved (Yao et al, 2006; Schoffelmeer et al, 2006; Rios et al, 2006).

Although AFR- and D-dronabinol rats received the same dronabinol treatment and washout period, opposite behavioral and neuroanatomical results were observed. THC inducing opposite behavioral responses has also been described in models of epilepsy and anxiety-like behavior in rodents (for review, see Pertwee, 2008). A possible explanation for these opposite data is to consider the now well-established characteristic of THC, a cannabinoid CB1 receptor partial agonist. The coupling efficiency of CB1 receptors, the firing rate of the synapse, and/or the endocannabinoid release have been recently proved to be involved in this pharmacological property. For example, THC may antagonize responses to endogenously released endocannabinoids by targeting CB1 receptors in a far less selective manner than endocannabinoids (for review, see Pertwee, 2008; Roloff and Thayer, 2009). Additional studies are now in progress in the laboratory to elucidate this hypothesis with special attention to the basal endocannabinoid levels in AFR and D rats.

These results reinforce the idea that the cannabinoid system has an important homeostatic control of enkephalinergic system activity and that the THC effect may differ according to the imbalance status of the system. Together, our data raise the question of its beneficial effect in an opiate dependence vulnerability context, particularly in subgroups of individuals subjected to adverse postnatal environments.

References

Andersen SL (2003). Trajectories of brain development: point of vulnerability or window of opportunity? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 27: 3–18.

Bardo MT, Bevins RA (2000). Conditioned place preference: what does it add to our preclinical understanding of drug reward? Psychopharmacology 153: 31–43.

Belue RC, Howlett AC, Westlake TM, Hutchings DE (1995). The ontogeny of cannabinoid receptors in the brain of postnatal and aging rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol 17: 25–30.

Biscaia M, Fernàndez B, Higuera-Matas A, Miguèns M, Viveros M-P, Garcìa-Lecumberri C et al (2008). Sex-dependent effects of periadolescent exposure to the cannabinoid agonist CP-55 940 on morphine self-administration behaviour and the endogenous opioid system. Neuropharmacology 54: 863–873.

Cadoni C, Pisanu A, Solinas M, Acquas E, Di Chiara G (2001). Behavioural sensitization after repeated exposure to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cross-sensitization with morphine. Psychopharmacology 158: 259–266.

Corchero J, Garcia-Gil L, Manzanares J, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ, Fuentes JA, Ramos JA (1998). Perinatal delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol exposure reduces proenkephalin gene expression in the caudate–putamen of adult female rats. Life Sci 63: 843–850.

Ellgren M, Spano SM, Hurd YL (2007). Adolescent cannabis exposure alters opiate intake and opioid limbic neuronal populations in adult rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 32: 607–615.

Gardner EL, Vorel SR (1998). Cannabinoid transmission and reward-related events. Neurobiol Disease 5: 502–533.

Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, De Costa BR, Rice KC (1991). Characterization and localization of cannabinoid receptors in rat brain: a quantitative in vitro autoradiographic study. J Neurosci 11: 563–583.

Howlett AC (1995). Pharmacology of cannabinoid receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 35: 607–634.

Hohmann AF, Herkenham H (2000). Localization of cannabinoid CB(1) receptor mRNA in neuronal subpopulations of rat striatum: a double-label in situ hybridization study. Synapse 37: 71–80.

Hoffman AF, Oz M, Caulder T, Lupica CR (2003). Functional tolerance and blockade of long-term depression at synapses in the nucleus accumbens after chronic cannabinoid exposure. J Neurosci 23: 4815–4820.

Jardinaud F, Roques BP, Noble F (2006). Tolerance to the reinforcing effects of morphine in delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol treated mice. Behav Brain Res 173: 255–261.

Kieffer BL (1999). Opioids: first lessons from knockout mice. Trends Pharmacol Sci 20: 19–26.

Lamarque S, Taghzouti K, Simon H (2001). Chronic treatment with delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol enhances the locomotor response to amphetamine and heroine. Implications for vulnerability to drug addiction. Neuropharmacology 41: 118–129.

Ledent C, Valverde O, Cossu G, Petitet F, Aubert JF, Beslot F et al (1999). Unresponsiveness to cannabinoids and reduced addictive effects of opiates in CB1, receptor knockout mice. Science 228: 401–404.

McKinney DL, Cassidy MP, Collier LM, Martin BR, Wiley JL, Selley DE et al (2008). Dose-related differences in the regional pattern of cannabinoid receptor adaptation and in vivo tolerance development to delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 324: 664–673.

Mansour A, Fox CA, Akil H, Watson SJ (1995). Opioid-receptor mRNA expression in the rat CNS: anatomical and functional implications. Trends Neurosci 18: 22–29.

Manzanedo C, Aguilar MA, Rodriguez-Arias M, Navarro M, Minarro J (2004). Cannabinoid agonist-induced sensitization to morphine place preference in mice. NeuroReport 15: 1373–1376.

Mason Jr DJ, Lowe J, Welch SP (1999). A diminution of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol modulation of dynorphin A(1–17) in conjunction with tolerance development. Eur J Pharmacol 381: 105–111.

Matsuda L, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI (1990). Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 346: 561–564.

Navarro M, Carrera MRA, Fratta W, Valverde O, Cossu G, Fattore L et al (2001). Functional interaction between opioid and cannabinoid receptors in drug self-administration. J Neurosci 15: 5344–5350.

Norwood CS, Cornish JL, Mallet PE, McGregor IS (2003). Pre-exposure to the cannabinoid receptor agonist CP 55940 enhances morphine behavioral sensitization and alters morphine self-administration in Lewis rats. Eur J Pharmacol 28: 105–114.

Paxinos G, Watson C (1997). The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press: New York.

Pertwee RG (2008). The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of the three plant cannabinoids: Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br J Pharmacol 153: 199–215.

Pickel VM, Chan J, Kash TL, Rodriguez JJ, Mackie K (2004). Compartment-specific localization of cannabinoid 1 (CB1) and μ opioid receptors in rat nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience 127: 101–112.

Pistis M, Perra S, Pillolla G, Melis M, Muntoni A-L, Gessa GL (2004). Adolescent exposure to cannabinoids induces long-lasting changes in the response to drugs of abuse of rat midbrain dopamine neurons. Biol Psychiatry 56: 86–94.

Rios C, Gomes I, Devi LA (2006). μ opioid and CB1 cannabinoid receptors interactions: reciprocal inhibition of receptor signaling and neuritogenesis. Br J Pharmacol 148: 387–395.

Rodriguez JJ, Mackie K, Pickel VM (2001). Ultrastructural localization of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor in mu-opioid receptor patches of the rat caudate putamen nucleus. J Neurosci 24: 1673–1679.

Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Ramos JA, Bonnin A, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ (1993). Presence of cannabinoid binding sites in the brain from early postnatal ages. Neuroreport 4: 135–138.

Roloff AM, Thayer SA (2009). Modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission by Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol switches from agonist to antagonist depending on firing rate. Mol Pharmacol 75: 892–900.

Romero J, Berrendero F, Manzanares J, Pérez A, Corchero J, Fuentes JA et al (1998). Time-course of the cannabinoid receptor down-regulation in the adult rat brain caused by repeated exposure to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Synapse 30: 298–308.

Rubino T, Vigano D, Massi P, Spinello M, Zagato E, Giagnoni G (2000). Chronic delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol treatment increases cAMP levels and cAMP-dependent protein kinase activity in some rat brain regions. Neuropharmacology 39: 1331–1336.

Schoffelmeer ANM, Hogenboom F, Wardeh G, De Vries TJ (2006). Interactions between CB1 cannabinoid and μ opioid receptors mediating inhibition of neurotransmitter release in rat nucleus accumbens core. Neuropharmacology 51: 773–781.

Shippenberg TS, Bals-Kubik R, Herz A (1993). of the neurochemical substrates mediating the motivational effects of opioids: role of the mesolimbic dopamine system and D-1 vs D-2 dopamine receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 265: 53–59.

Sim-Selley LJ (2003). Regulation of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the central nervous system by chronic cannabinoids. Crit Rev Neurobiol 15: 91–119.

Singh ME, McGregor IS, Mallet PE (2005). Repeated exposure to delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol alters heroin-induced locomotor sensitisation and Fos-immunoreactivity. Neuropharmacology 49: 1189–1200.

Singh ME, McGregor IS, Mallet PE (2006). Perinatal exposure to delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol alters heroin-induced place conditioning and Fos-immunoreactivity. Neuropsychopharmacology 31: 58–69.

Steiner H, Bonner TI, Zimmer AM, Kitai ST, Zimmer A (1999). Altered gene expression in striatal projection neurons in CB1 cannabinoid receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 5786–5790.

Tanda G, Goldberg SR (2003). Cannabinoids: reward, dependence, and underlying neurochemical mechanisms- a review of recent preclinical data. Psychopharmacology 169: 115–134.

Valverde O, Noble F, Beslot F, Daugé V, Fournié-Zaluski M-C, Roques BP (2001). Δ9—tetrahydrocannabinol releases and facilitates the effects of endogenous enkephalins: reduction in morphine withdrawal syndrome without change in rewarding effect. Eur J Neurosci 13: 1816–1824.

Van Ree JM, Niesink RJ, Van Wolfswinkel L, Ramsey NF, Kornet MM, Van Furth WR et al (2000). Endogenous opioids and reward. Eur J Pharmacol 405: 89–101.

Vazquez V, Weiss S, Giros B, Martres M-P, Daugé V (2007). Maternal deprivation and handling modify the effect of the dopamine D3 receptor agonist, BP 897 on morphine-conditioned place preference in rats. Psychopharmacology 193: 475–486.

Vazquez V, Penit-Soria J, Durand C, Besson MJ, Giros B, Daugé V (2005). Maternal deprivation increases vulnerability to morphine dependence and disturbs the enkephalinergic system in adulthood. J Neurosci 25: 4453–4462.

Vazquez V, Giros B, Daugé V (2006). Maternal deprivation specifically enhances vulnerability for opiate dependence. Behav Pharmacol 17: 715–724.

Yao L, McFarland K, Fan P, Jiang Z, Ueda T, Diamond I (2006). Adenosine A2a blockade prevents synergy between μ-opiate and cannabinoid CB1 receptors and eliminates heroin-seeking behavior in addicted rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 7877–7882.

Wolffgramm J, Heyne A (1995). From controlled drug intake to loss of control: the irreversible development of drug addiction in the rat. Behav Brain Res 70: 77–94.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the French Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique et Médicale (INSERM). LM has a fellowship supported by the French Mission Interministérielle de la Lutte contre la Drogue et la Toxicomanie (MILDT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

DISCLOSURE/CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morel, L., Giros, B. & Daugé, V. Adolescent Exposure to Chronic Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Blocks Opiate Dependence in Maternally Deprived Rats. Neuropsychopharmacol 34, 2469–2476 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.70

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.70

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Does cannabis use substitute for opioids? A preliminary exploratory survey in opioid maintenance patients

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2024)

-

Deconstructing the neurobiology of cannabis use disorder

Nature Neuroscience (2020)

-

Preclinical Studies of Cannabinoid Reward, Treatments for Cannabis Use Disorder, and Addiction-Related Effects of Cannabinoid Exposure

Neuropsychopharmacology (2018)

-

Intra-accumbal Cannabinoid Agonist Attenuated Reinstatement but not Extinction Period of Morphine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference; Evidence for Different Characteristics of Extinction Period and Reinstatement

Neurochemical Research (2017)

-

Keep off the grass? Cannabis, cognition and addiction

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2016)