Abstract

Hybridizing collective spin excitations and a cavity with high cooperativity provides a new research subject in the field of cavity quantum electrodynamics and can also have potential applications to quantum information. Here we report an experimental study of cavity quantum electrodynamics with ferromagnetic magnons in a small yttrium-iron-garnet (YIG) sphere at both cryogenic and room temperatures. We observe for the first time a strong coupling of the same cavity mode to both a ferromagnetic-resonance (FMR) mode and a magnetostatic (MS) mode near FMR in the quantum limit. This is achieved at a temperature ~22 mK, where the average microwave photon number in the cavity is less than one. At room temperature, we also observe strong coupling of the cavity mode to the FMR mode in the same YIG sphere and find a slight increase of the damping rate of the FMR mode. These observations reveal the extraordinary robustness of the FMR mode against temperature. However, the MS mode becomes unobservable at room temperature in the measured transmission spectrum of the microwave cavity containing the YIG sphere. Our numerical simulations show that this is due to a drastic increase of the damping rate of the MS mode.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hybrid quantum circuits combining two or more physical systems can harness the distinct advantages of different physical systems to better explore new phenomena and potentially bring about novel quantum technologies (for a review, see ref. 1). Among them, a hybrid system consisting of a coplanar waveguide resonator and a spin ensemble was proposed2 and experimentally utilized3–8 to implement both on-chip cavity quantum electrodynamics and quantum information processing. This spin ensemble is usually based on dilute paramagnetic impurities, such as nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond9,10 and rare-earth ions doped in a crystal.11 By increasing the density of the paramagnetic impurities, strong and even ultrastrong couplings between the cavity and the spin ensemble can be achieved, but the coherence time of the spin excitations is drastically shortened. Indeed, it is a challenging task to realize both good quantum coherence of the spin ensemble and its strong coupling to a cavity.

Very recently, collective spins in a yttrium-iron-garnet (YIG) ferromagnetic material were explored to achieve their strong12–14 and even ultrastrong couplings15 to a microwave cavity. In contrast to spin ensembles based on dilute paramagnetic impurities, these spins12 are strongly exchange-coupled and have a much higher density (~4.2×1021 cm−3). Because of this high spin density, a strong coupling of the spin excitations to the cavity can be easily realized using a YIG sample as small as sub-milimeter in size. Also, the ultrastrong coupling regime becomes readily reachable by either increasing the size of the YIG sample or using a specially designed microwave cavity.15 Moreover, the contribution of magnetic dipole interactions to the linewidth of spin excitations, which can have a dominant role among paramagnetic impurities, is suppressed by the strong exchange coupling between the ferromagnetic electrons.16 Thus, when the same spin density is involved, the spin excitations in YIG can exhibit much better quantum coherence than those of the paramagnetic impurities.

The YIG material is ferromagnetic at both cryogenic and room temperatures because its Curie temperature is as high as 559 K. Indeed, a strong coupling between a microwave cavity and the collective spin excitations related to the ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) was observed in different YIG samples at either cryogenic12,13,15 or room temperature.14 Here we report a direct observation of the strong coupling between FMR magnons and microwave photons at both cryogenic and room temperatures by using the same small YIG sphere in a three-dimensional (3D) cavity. This allows us to directly compare the quantum coherence of the same FMR mode at both cryogenic and room temperatures. We explain why the FMR spin excitations can be described as non-interacting magnons even at room temperature and its extraordinary robustness against temperature. Moreover, at cryogenic temperatures, we have also observed a strong coupling of the microwave photons to another collective spin mode, i.e., a magnetostatic (MS) mode, near the FMR. We find that this newly observed collective mode of spins exhibits quantum coherence nearly as good as the FMR mode. In addition, this collective spin mode can also be described as non-interacting magnons at room temperature, but becomes unobservable due to the drastic decrease of its quantum coherence. In short, compared to very recent studies,12–15 our experiment demonstrates for the first time the experimentally achieved strong coupling of both FMR and MS modes to the same cavity mode and unveils quantum-coherence properties of the ferromagnetic magnons at both cryogenic and room temperatures.

Results

Experimental setup and model Hamiltonian

We illustrate the experimental setup in Figure 1. A small YIG sphere with a diameter of 0.32 mm is mounted in a 3D rectangular microwave cavity with dimensions 50×18×3 mm3 (Figure 1a). The frequency of the fundamental cavity mode TE101 is measured to be ωc,1/2π=8.855 GHz and the frequency of the second cavity mode TE102 is ωc,2/2π=10.306 GHz (Supplementary Material). By adjusting the lengths of the pins inside the input and output ports, the coupling rates related to these ports are tuned to κi,1/2π=0.19 MHz and κo,1/2π=0.20 MHz for mode TE101, and κi,2/2π=0.85 MHz and κo,2/2π=0.99 MHz for mode TE102. To achieve strong couplings between the YIG sample and these two cavity modes, we place the YIG sphere at the center of one short edge of the rectangular cavity where both cavity modes, TE101 and TE102, have stronger magnetic fields parallel to the short edge (Figure 1b,c). In our experiment, the YIG sphere is mounted, so that the microwave magnetic fields of the cavity modes TE101 and TE102 at the YIG sphere are nearly parallel to the crystalline axis 〈110〉. Also, a static magnetic field perpendicular to the microwave magnetic field and parallel to the crystalline axis 〈100〉 of the YIG sphere is applied. This static magnetic field can be tuned to drive the magnons in resonance with the cavity modes TE101 and TE102, respectively.

A high-finesse 3D microwave cavity containing a small YIG sphere. (a) The experimentally used rectangular 3D cavity is made of oxygen-free copper and has dimensions 50×18×3 mm3. The upper panel shows the top cover of the cavity, where two connectors are attached for microwave transmission. In the lower panel, a small YIG sphere with a diameter of 0.32 mm is mounted at the center of one short edge of the rectangular cavity. The inset at the left is a magnified picture of the YIG sphere. (b) Simulated magnetic-field distribution of the fundamental cavity mode TE101. (c) Simulated magnetic-field distribution of the second cavity mode TE102. A static magnetic field B0 is applied parallel to the long edge of the cavity, and the microwave magnetic field at the YIG sphere is perpendicular to the static magnetic field.

For a small YIG sample embedded in a microwave cavity, we observed a strong coupling between the fundamental cavity mode and the FMR mode, i.e., the Kittel mode (see Figure 2a), as also reported in refs 12–15. This FMR corresponds to a collective mode of spins with zero wavevector (i.e., in the long-wavelength limit) at which all exchange-coupled spins uniformly precess in phase together. In addition to this FMR, there are other long-wavelength collective modes of spins called the magnetostatic (MS) modes.17,18 These MS modes are also called dipolar spin waves under magnetostatic approximation, where the magnetic dipolar interactions dominate both the electric and exchange interactions.19 In this condition, the wave number kMS of a MS mode satisfies , where is the wave number of the microwave field propagating in the YIG material and the exchange constant is Λex=3×10−16 m2. Meanwhile, the microwave magnetic field h related to a MS mode of the YIG sphere satisfies the magnetostatic equation19

where D is the microwave electric displacement vector and the magnetization m is excited by h. The right side of equation (1) is approximately zero because kMS>>k0, and the equation ∂D/∂t≈0 implies that the MS modes are essentially static. Also, like the FMR mode, the MS modes are discrete modes constrained by the boundary condition of the YIG sphere. Because the magnetic dipolar interactions dominate the exchange interactions, these modes are also called rigid discrete modes. However, unlike the FMR mode with uniform precession, the MS modes are non-uniform precession modes holding inhomogeneous magnetization and have a spatial variation comparable to the sample dimensions.17–19

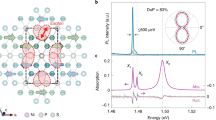

Strong magnon–photon coupling achieved at cryogenic temperature. In (a–d), the transmission spectrum of the rectangular 3D cavity with a small YIG sphere is measured as a function of the static magnetic field at 22 mK in a dilution refrigerator. The input microwave power is (a) −130 dBm with different frequencies around TE101, (b) −130 dBm with different frequencies around TE102, (c) −100 dBm with different frequencies around TE101, and (d) −100 dBm with different frequencies around TE102. The horizontal dashed lines denote the resonant frequencies of the cavity and the tilted dashed lines show the magnetic-field dependence of the frequencies of the FMR (left) and MS (right) modes. The green solid curves correspond to the energy levels of the magnon–polariton obtained by diagonalizing the Hamiltonian in equation (3).

Here we utilize the transmission spectrum of the microwave cavity to demonstrate for the first time the experimentally-achieved strong coupling of both FMR and MS collective modes to the same mode (either the fundamental or second mode) of the 3D rectangular cavity. Because the FMR and MS modes are long-wavelength rigid discrete modes of spins in the YIG sphere, the exchange interactions between electron spins can be neglected.18,20 Thus, similar to the model Hamiltonian in refs 21,22, when the FMR and a MS mode are both involved, the YIG-cavity Hamiltonian can be written as (setting ħ=1)

where ωc is the angular frequency of the cavity mode considered (either TE101 or TE102), g the electron g-factor, and μB the Bohr magneton; and are the effective magnetic fields experienced, respectively, by the FMR and MS modes of the YIG sphere; while a† (a) is the photon creation (annihilation) operator and gFMR(MS) is the coupling strength of the cavity mode to a single spin in the FMR (MS) mode. Because the frequencies of different cavity modes are away from each other, we can then write a separate Hamiltonian for each cavity mode. The collective spin operators are given by , where , and m=FMR (MS) denotes the FMR (MS) mode. These collective spin operators are related to the magnon operators via the Holstein–Primakoff transformation: , , and , where S(m) is the total spin number of the corresponding collective spin operator. For the low-lying excitations with , one has , and , i.e., the collective spin excitations can be described as non-interacting magnons. Then, the Hamiltonian (2) is reduced to

where is the angular frequency of the magnon mode (either FMR or MS mode) and is the corresponding magnon–photon coupling strength. By diagonalizing the Hamiltonian in equation (3), we obtain the energy levels of the magnon–polariton (see the green curves in Figure 2).

Experimental measurements at cryogenic temperature

An avoided crossing occurs around ωc=ωFMR (ωMS) because of the strong coupling between the cavity mode and the FMR (MS) mode. Thus, three magnon–polariton branches appear (see the green curves in Figure 2a). By fitting the experimental results in Figure 2a with equation (3), we find that , for the case of the fundamental cavity mode TE101 coupled to the FMR and MS modes, respectively. However, when the second cavity mode TE102 interacts with the FMR and MS modes, the corresponding coupling strengths increase to and (Figure 2b). It can be seen that the coupling strength between the cavity mode and the FMR mode does not change much when shifting the cavity mode from TE101 to TE102, but the coupling strength between the cavity mode and the MS mode changes drastically from TE101 to TE102. Surprisingly, when the cavity mode is TE102. This is because of a better overlap between the MS mode and the second cavity mode. In YIG, the only magnetic ions are the ferric ions with spin number s=5/2. Since the FMR mode involves uniform, in-phase precession of all spins in the YIG sphere, one has S(FMR)=Ns, where N is the total number of spins. Therefore, it is natural to obtain . The coupling strength of a single spin to the cavity mode can be calculated by14 , where Vc is the volume of the cavity mode with frequency ωc, γe=2π×28.0 GHz/T is the gyromagnetic ratio, and the overlap coefficient η describes the spatial overlap and polarization-matching conditions between the cavity and magnon modes. With our experimental parameters, the calculated gFMR/2π is 15.8 mHz for the cavity mode TE101. Thus, from the experimentally obtained , the total number of spins is estimated to be N~2.3×1016.

To obtain damping rates of the FMR and MS modes, we further fit our experimental results with the calculated transmission coefficient of the microwave cavity containing a YIG sphere. In a standard input-output theory (see, e.g., ref. 23), this transmission coefficient can be written as

where κi (κo) is the corresponding input (output) dissipation rate due to the coupling between the feed line and the cavity. The total cavity decay rate is given by κtot=κi+κo+κint, with κint being the intrinsic loss rate of the cavity. The self-energy , where ωFMR is the angular frequency of the FMR mode, which has a damping rate γFMR, and ωMS is the angular frequency of the MS mode with a damping rate γMS. Using S21 in equation (4) to fit the experimental results (see Supplementary Material for the simulated transmission spectra), we can evaluate the damping rates γFMS and γMS as well as the total decay rate κtot of the cavity. These evaluated parameters and the calculated cooperativity are summarized in Table 1. The experimental parameters show that , with a cooperativity in most cases, indicating that the strong coupling regime is reached when both FMR and MS modes in the YIG sphere interact with the same cavity mode. In the experiment of Figure 2, the measurements were implemented at 22 mK using a dilution refrigerator. This very low temperature corresponds to a negligible average thermal photon number in the 3D cavity (e.g., ~1×10−2 for the fundamental cavity mode). Accordingly, for the probe microwave tone in the measurements, we used a very weak input power of −130 dBm in Figure 2a,b and a weak input power of −100 dBm in Figure 2c,d, which correspond to average microwave photon numbers ~0.8 and 800, respectively, for the fundamental cavity mode. Note that the measured transmission spectra in Figure 2c, d are very close to those in Figure 2a, b, even though the average microwave photon number in the cavity has increased from ~0.8 to 800. Owing to the small number of photons in the cavity, especially in the case of −130 dBm, the measured results clearly show that a strong magnon–photon coupling has been experimentally achieved in the quantum regime for both the FMR and MS modes coupled to the same cavity mode. Moreover, because γMS~2γFMR at 22 mK (Table 1), the experimental results reveal that the newly observed MS mode exhibits quantum coherence nearly as good as the FMR mode at cryogenic temperature.

Experimental measurements at room temperature

As an explicit comparison, we also measured, at room temperature, the transmission spectrum of the 3D microwave cavity containing the same YIG sphere (Figure 3). Now the average number of thermal photons becomes larger (e.g., ~1×103 at 300 K for the fundamental cavity mode), so one has to use a probe microwave tone with higher power. In Figure 3, the input microwave power is −20 dBm, which corresponds to an average microwave photon number ~1.8×1010 for the fundamental cavity mode. Similar to the experimental observations in ref. 14, at room temperature, an avoided crossing also occurs when the applied static magnetic field is tuned to make the FMR mode in resonance with the cavity mode TE101 or TE102. This reveals that the low-lying excitation condition is satisfied for the FMR mode even at room temperature, because the FMR-cavity Hamiltonian can be reduced to a form similar to equation (3), where the FMR mode is described by non-interacting magnons. This is due to the fact that the FMR mode involves the uniform precession of all spins, such that S(FMR)=Ns, where the total number N of spins in the YIG sphere is many orders of magnitude greater than unity. Moreover, based on the fitting results for the same YIG sphere, the damping rate of the FMR mode is found to slightly increase from 1.2 MHz (1.3 MHz), at ~22 mK, to 1.3 MHz (1.5 MHz) at room temperature, when the frequency of the FMR mode is close to the fundamental (second) cavity mode (Table 1). These results reveal that the FMR mode is robust against temperature. The damping rate of the FMR mode obtained here is comparable to that in ref. 14, where cavity quantum electrodynamics with a YIG sphere of 0.36 mm in diameter was investigated only at room temperature. Note that the only magnetic ions in YIG are the ferric ions. Because these ions are in an L=0 state with a spherical charge distribution, their interaction with lattice deformations and phonons is weak16. As a result, the FMR mode which involves the uniform precession of all spins is only weakly affected by phonons. This explains why the obtained damping rate of the FMR mode does not change much from cryogenic to room temperatures.

Strong coupling of the FMR mode to two cavity modes at room temperature. The transmission spectrum of the rectangular 3D cavity containing the same YIG sphere is measured at room temperature as a function of the static magnetic field. The input microwave power is −20 dBm with different frequencies around (a) TE101 and (b) TE102, respectively.

For the MS mode, the avoided crossing observed at cryogenic temperatures disappears at room temperature (comparing Figure 3 with Figure 2). This disappearance of the MS mode may be due to (i) the low-lying excitation condition for the MS mode is not satisfied at room temperature, and (ii) the strong magnon–photon coupling regime was not reached. When the frequency of the MS mode is close to the cavity mode, at room temperature. The low-lying excitation condition is not followed if . However, at cryogenic temperatures, the observed transmission spectrum shows that is comparable to (Table 1). Thus, S(MS)~S(FMR), implying that for the MS mode, the low-lying excitation condition is still satisfied even at room temperature. Therefore, the first possibility is ruled out for the disappearance of the MS mode at room temperature. In Figure 4, we present numerical simulations of the transmission spectrum around the frequency of the cavity mode TE102, by increasing the damping rate of the MS mode. It can be seen that when the damping rate γMS is increased by two orders of magnitude, the simulated transmission spectrum agrees well with the experimental result obtained at room temperature (comparing Figure 4c with Figure 3b). This damping rate is much larger than the coupling strength , corresponding to a weak-coupling regime between the MS mode and the cavity mode. Therefore, in the transmission spectrum, the disappearance of the MS mode at room temperature can be attributed to the drastic increase of the MS-mode damping rate with temperature.

Impact of the MS-mode damping rate on the transmission spectrum. In (a–c), numerical simulations of the transmission spectrum are performed using equation (4) by choosing different input microwave frequencies around TE102. The parameters for both the cavity and FMR modes are the same as the measured values in Figure 3b. For the MS mode, the parameters are the same as the measured value in Figure 2b, but its damping rate increases from (a) γMS=3.3 MHz, to (b) 10γMS, and then to (c) 100γMS.

Discussion

Note that the experimental results in ref. 13 show that the linewidth of the FMR mode increased more than three times when the temperature was raised from ~10 mK to ~10 K. This observed linewidth increase of the FMR mode with the temperature was ascribed to the slow-relaxation process due to the impurity ions and magnon–phonon scattering13. In contrast, the damping rate (i.e., the linewidth) of the FMR mode in our YIG sphere does not show an appreciable contribution from this slow-relaxation process, because γFMR slightly increases when raising the temperature from 22 mK to room temperature (Table 1). Thus, our YIG sample is of a better quality than that in ref. 13, regarding the quantum coherence of the FMR mode. In ref. 14, cavity quantum electrodynamics with a YIG sphere of 0.36 mm in diameter was studied at room temperature. The obtained damping rate of the FMR mode is ~1.1 MHz, which is also comparable to our result at room temperature. Moreover, for YIG doped with gallium, it was reported24 that the linewidth of the FMR mode decreases from 1 mT at 4.2 K to 0.1 mT at room temperature, corresponding to 28 and 2.8 MHz, respectively. This counter-intuitive observation of the linewidth narrowing for increasing temperature is different from both our results and those in ref. 13. Therefore, the linewidth of the FMR mode in the YIG material and the corresponding quantum-coherence behavior raise interesting open questions for further investigations. In our experiment, only measurements at cryogenic and room temperatures were implemented due to limitations in the experimental facility, so it is desirable (though challenging) to perform measurements at the wide-range intermediate temperatures, so as to provide more insights into the damping mechanism of the magnons.

In ref. 15, the ultrastrong coupling between the FMR mode and the bright mode of a reentrant cavity was observed at 20 mK by using a larger YIG sphere (~0.8 mm in diameter) attached to the reentrant cavity. In addition, a strong coupling between a MS mode and the dark mode of the reentrant cavity was also observed. In sharp contrast to our observations, the cavity mode coupled to the FMR mode and the cavity mode coupled to the MS mode were not the same mode of the reentrant cavity. Moreover, in ref. 15, the cavity-MS mode coupling was much weaker than the cavity-FMR mode coupling. This is also very different from our results and might be due to the different symmetries of the relevant magnon modes or the material properties of the YIG sphere.

In conclusion, we have experimentally studied cavity quantum electrodynamics with ferromagnetic magnons in a small YIG sphere at both cryogenic and room temperatures. We observed strong coupling of the same cavity mode to both FMR and MS modes in the quantum limit at ~22 mK. Also, we observed strong coupling of the cavity mode to the FMR mode at room temperature, with the damping rate of the FMR mode only slightly increased. This reveals the robustness of the FMR mode against temperature. Moreover, we find that the MS mode disappears at room temperature in the measured transmission spectrum and also numerically show that this is due to a drastic increase of the damping rate of the MS mode. Our work unveils quantum-coherence properties of the ferromagnetic magnons in a YIG sphere at both cryogenic and room temperatures, especially the extraordinary robustness of the FMR mode against temperature.

Methods

Sample preparation

The rectangular 3D cavity was produced using oxygen-free high-conductivity copper and its inner faces were highly polished. Also, this cavity was designed to have two connector ports for measuring microwave transmission. A commercially sold YIG sphere with a diameter of 0.32 mm was made by China Electronics Technology Group Corporation 9th Research Institute. This YIG sphere was mounted in the rectangular 3D cavity and the measurement of the microwave transmission through the cavity was implemented at both cryogenic and room temperatures.

Measurement

An Oxford Triton 400-10 cryofree dilution refrigerator (DR) was employed for the cryogenic measurement and a temperature as low as 22 mK was achieved at the mixing chamber stage of the DR. The cavity was placed in the mixing chamber stage and applied a static magnetic field using a superconducting magnet. In order to prevent the room-temperature thermal noise from the input lines, we used a series of attenuators to reach a total attenuation of 100 dB. For the output line, a circulator was attached to achieve an isolation ratio of 30 dB. Then, the transmitted signal from the cavity was amplified via a series of amplifiers both at the 4 K stage and outside of the DR. The microwave transmission measurement was performed using a vector network analyzer (VNA; Agilent N5030A, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). To adjust the average photon number in the cavity, the input microwave power was tuned to be either −30 dBm or 0 dBm. Because of the total attenuation of 100 dB on the input lines, the final input power in the cavity becomes −130 dBm or −100 dBm.

For the room-temperature measurement, the same cavity with the YIG sphere was placed in a static magnetic field generated by an electromagnet (made by Beijing Cuihaijiacheng Magnetic Technology, Beijing, China). The transmission spectrum of the hybrid system was measured using a VNA (Agilent N5232A) directly connected to two ports of the cavity with an input power of −20 dBm.

References

Xiang, Z. L., Ashhab, S., You, J. Q. & Nori, F. Hybrid quantum circuits: Superconducting circuits interacting with other quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 623–653 (2013).

Imamoğlu, A. Cavity QED based on collective magnetic dipole coupling: Spin ensembles as hybrid two-level systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 083602 (2009).

Kubo, Y. et al. Strong coupling of a spin ensemble to a superconducting resonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 140502 (2010).

Amsüss, R. et al. Cavity QED with magnetically coupled collective spin states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 060502 (2011).

Schuster, D. I. et al. High-cooperativity coupling of electron-spin ensembles to superconducting cavities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 140501 (2010).

Bushev, P. et al. Ultralow-power spectroscopy of a rare-earth spin ensemble using a superconducting resonator. Phys. Rev. B. 84, 060501 (2011).

Probst, S. et al. Anisotropic rare-earth spin ensemble strongly coupled to a superconducting resonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 157001 (2013).

Ranjan, V. et al. Probing dynamics of an electron-spin ensemble via a superconducting resonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 067004 (2013).

Wrachtrup, J. & Jelezko, F. Processing quantum information in diamond. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 18, S807–S824 (2006).

Doherty, M. W. et al. Theory of the ground-state spin of the NV− center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B. 85, 205203 (2012).

Guillot-Noël, O. et al. Hyperfine interaction of Er3+ ions in Y2SiO5: an electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Phys. Rev. B. 74, 214409 (2006).

Huebl, H. et al. High cooperativity in coupled microwave resonator ferrimagnetic insulator hybrids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 127003 (2013).

Tabuchi, Y. et al. Hybridizing ferromagnetic magnons and microwave photons in the quantum limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 083603 (2014).

Zhang, X., Zou, C.-L., Jiang, L. & Tang, H. X. Strongly coupled magnons and cavity microwave photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 156401 (2014).

Goryachev, M. et al. High-cooperativity cavity QED with magnons at microwave frequencies. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2, 054002 (2014).

Kittel, C . Introduction to Solid State Physics. 8th edn (John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

Walker, L. R. Resonant modes of ferromagnetic spheroids. J. Appl. Phys. 29, 318–323 (1958).

Fletcher, P. C. & Bell, R. O. Ferrimagnetic resonance modes in spheres. J. Appl. Phys. (1959); 30, 687–698 (1959).

Stancil, D. D. & Prabhakar, A . Spin Waves (Springer, 2009).

White, R. M . Quantum Theory of Magnetism. 3rd edn (Springer, 2007).

Soykal, Ö. O. & Flatté, M. E. Strong field interactions between a nanomagnet and a photonic cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 077202 (2010).

Soykal, Ö. O. & Flatté, M. E. Size dependence of strong coupling between nanomagnets and photonic cavities. Phys. Rev. B. 82, 104413 (2010).

Walls, D. F. & Milburn, G. J . Quantum Optics. (Springer, 1994).

Rachford, F. J., Levy, M., Osgood, R. M., Kumar, A. & Bakhru, H. Magnetization and FMR studies of crystal-ion-sliced narrow linewidth gallium-doped yttrium iron garnet. J. Appl. Phys. 87, 6253–6255 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the NSAF Grant No. U1330201, the NSFC Grant No. 91421102, and the MOST 973 Program Grant Nos. 2014CB848700 and 2014CB921401. FN is partially supported by the RIKEN iTHES Project, the MURI Center for Dynamic Magneto-Optics, the impact program of JST, and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JQY and TFL designed the experiments. DZ, XMW and TFL performed the experiments. JQY, FN, DZ and TFL wrote the paper with contributions from all authors. The interpretation of the results was contributed by all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the npj Quantum Information website (http://www.nature.com/npjqi)

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, D., Wang, XM., Li, TF. et al. Cavity quantum electrodynamics with ferromagnetic magnons in a small yttrium-iron-garnet sphere. npj Quantum Inf 1, 15014 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/npjqi.2015.14

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npjqi.2015.14

This article is cited by

-

Quantifying Entanglement by Purity in a Cavity-Magnon System

Brazilian Journal of Physics (2024)

-

Dissipative dynamics of optomagnonic nonclassical features via anti-Stokes optical pulses: squeezing, blockade, anti-correlation, and entanglement

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Nonreciprocal microwave transmission under the joint mechanism of phase modulation and magnon Kerr nonlinearity effect

Frontiers of Physics (2023)

-

Recent progress on optomagnetic coupling and optical manipulation based on cavity-optomagnonics

Frontiers of Physics (2022)

-

Steady-state entanglement in a mechanically coupled double cavity containing magnetic spheres

Quantum Information Processing (2022)