Abstract

The bulk photovoltaic effect (BPVE) refers to the generation of a steady photocurrent and above-bandgap photovoltage in a single-phase homogeneous material lacking inversion symmetry. The mechanism of BPVE is decidedly different from the typical p–n junction-based photovoltaic mechanism in heterogeneous materials. Recently, there has been renewed interest in ferroelectric materials for solar energy conversion, inspired by the discovery of above-bandgap photovoltages in ferroelectrics, the invention of low bandgap ferroelectric materials and the rapidly improving power conversion efficiency of metal halide perovskites. However, as long as the nature of the BPVE and its dependence on composition and structure remain poorly understood, materials engineering and the realisation of its true potential will be hampered. In this review article, we survey the history, development and recent progress in understanding the mechanisms of BPVE, with a focus on the shift current mechanism, an intrinsic BPVE that is universal to all materials lacking inversion symmetry. In addition to explaining the theory of shift current, materials design opportunities and challenges will be discussed for future applications of the BPVE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The photovoltaic (PV) effect, which is the direct conversion of light to electricity, is regarded as one of the most reliable and abundant sources of renewable and clean energy. The power conversion efficiency (PCE, η) of a solar cell depends on a number of factors:

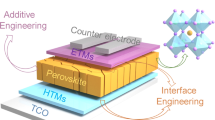

Here Voc is the open-circuit voltage, Jsc is the short-circuit current, FF is the fill factor and Pin is the power of the incident radiation on the solar cell. These quantities can be measured from the current–voltage (I–V) curve, as shown in Figure 1. In traditional solar cells, the mechanism for separation of the photoexcited carriers (electrons and holes) is the built-in electric field inside p–n junctions. Hot carriers typically relax to the bandedges via inelastic scattering events before being collected at the electrodes. These energy losses hamper the improvement of the PCE and limit the Voc to the bandgap of light-absorbing semiconductors. In addition, the requirement of p–n junctions for carrier separation demands careful interface engineering and sophisticated fabrication techniques.

(a) Schematic of solar cell output current as a function of voltage, for a shift current solar cell, displaying the linear relationship between current and voltage. Also shown are short-circuit current Jsc and open-circuit voltage Voc points, and maximum power point, Pmax. (b, c) Schematics of device geometry, for current flow along (b) and perpendicular (c) to the illumination direction. The green bar indicates the position of the electrodes.

In this review article, we discuss the bulk photovoltaic effect (BPVE), in particular, the shift current mechanism, which has a number of advantages over traditional p–n junction-based solar cells. In the shift current mechanism, the driving force for carrier separation is not the built-in electric field, but the coherent evolution of electron and hole wavefunctions. Although the carriers in p–n junctions travel to the electrodes via drift-diffusive transport, shift current carriers instead rapidly propagate to the electrodes, minimising the opportunity for energy losses. Because this is a hot carrier effect, carrier separation does not depend on any internal electric fields (see the ‘Polarisation’ section), above-bandgap photovoltages can be generated, and the Shockley–Queisser limit could be surpassed. Because the shift current mechanism relies only on bulk inversion asymmetry, it can be realized in single-phase materials. The lack of p–n interface ensures that the entire PV material is active for current generation and allows for a simple and robust fabrication process.

In general, the symmetry requirement to produce a current from unpolarised light is to have a structure that allows for the definition of a unique spatial vector (i.e., a polar material). Therefore, materials with bulk inversion symmetry cannot generate photocurrents in the bulk. Materials that have broken bulk inversion symmetry but are non-polar (e.g., GaAs) can generate bulk photocurrents, but only in response to polarised light.1 Ferroelectric materials, which have a switchable polarisation direction, satisfy the symmetry requirements for the generation of bulk photocurrents, and have historically been among the most studied BPVE materials.2–4 However, the switchable aspect is not a necessity for the observation of BPVE. In addition, we will show below (see the section ‘Polarisation’) that the BPVE response is not simply a measure of the strength of this polarisation field.

There are a number of BPVEs closely related to the shift current. Photocurrents can be generated in the bulk when scattering sites or absorption centres possess some amount of asymmetry.4–6 Such processes rely on the generation of an asymmetric distribution of nonthermalised carriers, in contrast to the coherent evolution in the shift current mechanism. These ballistic photocurrents have been discussed in ref. 7. In gyrotropic crystals, the switching of photocurrent directions with the helicity of circularly polarised light is known as the circular photogalvanic effect. In metals and semiconductors, under the assumptions of low frequencies and short relaxation times, this effect is controlled by the anomalous velocity that arises from orbital Berry phases.8–10 The circular photogalvanic effect has been experimentally observed in quantum wells.11–14 It has also been observed in tellurium crystals with significant spin–orbit valence band splittings.4,15

The shift current BPVE has been observed in many materials systems, including ferroelectrics,2,3,16 quantum wells,17 organic crystals18 and two-dimensional interfaces.19 The shift current theory was proposed as an explanation for the BPVE in BaTiO3 by von Baltz and Kraut,1 and was later derived within the framework of Green’s functions20 and nonlinear optics.21 Young and Rappe reformulated the shift current theory to enable efficient calculation from first-principles,22 and provided the first comparison of experimental BPVE data with shift current theory.22 In subsequent first-principles studies of the shift current in ferroelectric materials, it was shown that the shift current is the main contributor to the BPVE.23–30 As such, we will focus on the shift current.

In this review article, we provide an introduction to the basic theory and phenomenology of the shift current BPVE, with the aim of reviewing recent major developments in the field. In particular, there have been many recent efforts to increase shift current densities and efficiencies, and this will be the main focus of this review. We begin with a theoretical review of the shift current response, developed within the framework of a time-dependent perturbation theory, in the section ‘Theory of the shift current response’. In the section ‘Material properties conducive to shift current response’, we will discuss intrinsic material properties conducive to shift current response with a tight-binding model. After a review of recent experimental studies of ferroelectric and polar materials for solar energy conversion in the section ‘Review of experiments’, we present first-principles studies of the shift current response in various real materials, with an emphasis on oxide and halide perovskites, in the section ‘Modern materials design for shift current’. The review concludes with a consideration of new directions for realising BPVE-based solar cells.

Theory of the shift current response

In the shift current mechanism, the behaviour of carriers immediately after excitation by light is governed by coherent excitation instead of inelastic scattering. The time-dependent perturbation theory should therefore provide a good description of the electronic behaviour at these timescales. We first present a simplified derivation of the shift current in a three-level system: the energy level n=0 is initially occupied, whereas the levels n=1 and n=2 are initially unoccupied. In the presence of an electric field E oscillating at frequency ω, the electron at n=0 evolves into a linear combination of n=0, 1 and 2. Within a first-order time-dependent perturbation theory, this state is

with the coefficients

Here Vn0 and ωn0 are the dipole matrix element and energy difference between the levels n and 0. The current carried by the state ψ(t) is given by , where P is the momentum operator and contains both oscillatory and constant components. The contribution to the constant current from the first-order wavefunction is

where are phases derived from equation (3). The constant component of the current depends quadratically on the optical field and is a nonlinear optical effect. We note that the shift current also contains contributions from the momentum matrix elements between zeroth- and second-order wavefunctions in a time-dependent perturbation theory (SMY and AMR, unpublished data).

Equations (2, 3, 4) describe the picture of electrons in a coherent, current-carrying excited state ψ(t) that arises in an oscillating light field. Equivalently, these equations imply that an electron can be excited from the ground state 0 to a higher state n by a photon of frequency +ω, or it can be excited to a higher state by a photon of frequency −ω. These two different excitation amplitudes interfere, giving a d.c. response, provided that the amplitudes interfere asymmetrically. That is, the matrix element describing the interference, in equation (4), does not vanish by symmetry. In real materials, this asymmetry is manifested in the different spatial character of conduction and valence bands.31 Heuristically, this causes the electrons (and holes) to ‘shift’ on excitation by light.

In general, the shift current J is related to the electric field via the frequency- and material-dependent response function σ. In components:

Equation (5) shows that σrsq is a second-order response function. The direction of the shift current is not necessarily the same as the applied electric field, as can be seen from the tensorial property of σrsq. The second-order nature of the shift current response already imposes certain symmetry constraints on the classes of materials that can exhibit nonzero shift current response. In a material with inversion symmetry, the response function σ is left unchanged by an inversion operation, whereas the current and electric field, being vector quantities, each pick up a negative sign.

Using equation (6) in the constitutive equation (equation (5)) then implies that Jq=0 in such an inversion symmetric system. The shift current response can only be observed in materials with broken inversion symmetry. In the following sections, we will elaborate on the microscopic interpretation of this observation.

In crystalline materials, the response function can be written as an integral over the Brillouin zone.24

where c and v are conduction and valence bands, respectively. The derivation of this integral is provided in ref. 21 using nonlinear susceptibilities and in ref. 20 using Green’s functions. Like linear absorption, the shift current response depends on the momentum matrix elements on a constant energy difference manifold given by ωc−ωv=ω. There is an additional factor Rq(c, v, k) that has dimensions of length and is known as the shift vector.20,21 In terms of the conduction and valence band wavefunction,

Here φvc(k) is the phase of the transition dipole, and is the Berry connection for band c, in terms of the Bloch functions uc(k). Although each of the individual terms in equation (8) depends on the arbitrary gauge of the wavefunctions, their sum is gauge-independent and is a well-defined physical quantity.22 Furthermore, by expressing the electric field in terms of the light intensity, the shift current response susceptibility can be shown to be proportional to light intensity. Although the shift current expression in equation (7) is appropriate for thin samples without significant attenuation of the incident light, corrections have to be made for bulk crystals where the light intensity is inhomogeneous. In the latter, where the light intensity is fully attenuated by the sample, the shift current is related to the incident light intensity by the Glass coefficient3

where w is the width of the crystal surface exposed to illumination and αrr is the absorption coefficient and Ir the light intensity along the direction of incident light polarisation. We will study both the shift current response function and the Glass coefficient in the following sections.

The PCE of the shift current mechanism we have described in this section is not the subject to the same limitations as ordinary photocurrent.32 As the shift current is generated by the incident illumination and does not depend on an external voltage, the photovoltage is not limited by the bandgap. In addition, the shift current is generally found to be insensitive to photovoltage, so that that total current is

where V is the photovoltage, JSC is the short-circuit shift current density, L is the distance between electrodes, and σd and σph are the dark and photoconductivities, respecitively. Thus, the relationship between photovoltage and photocurrent is linear,33 implying a maximum fill factor of 0.25 (Figure 1a). The open-circuit photovoltage VOC is then achieved when the shift current is fully cancelled by the backflow of conventional current that occurs due to thermalised carriers driven by the photovoltage. Thus, in the limit of a thin sample, and assuming that dark conductivity is negligible,

The maximum power that may be drawn is where AJ is the area through which JSC flows. The total power absorbed by the sample is IAIαd, where I is the intensity, AI is the area illuminated, α is the absorption coefficient and d is the sample depth. The efficiency is then . At this point, we must recognise that there are at least two possible cell geometries. In the first, the electrode faces are normal to the illumination direction (Figure 1b), whereas in the second the electrode normal is perpendicular to the illumination direction (Figure 1c). In the former case, AI=AJ and d=L, so that

If we assume that the photoconductivity is proportional to the number of carriers excited, then we may take it to be σph=cμαI, where μ is the mobility, and we have

The same result may be obtained in the thin-film limit for the second geometry. From this, it is clear that high efficiency requires maximising the Glass coefficient and minimising the mobility. The latter may be accomplished by creating heterostructures that feature regions with low mobility that the shift current is nonetheless able to flow through. An example of such a strategy was presented in ref. 34, where the authors show that domain walls of BFO possess very low photoconductivity, preventing carriers leaking back through the sample.

In this discussion of shift current efficiency, we have neglected the recombination current. In principle, geminate recombination of an electron–hole pair, which occurs before the electron and hole have separated, can result in a recombination current opposing the shift current, reducing the magnitude of the total photocurrent. However, in the usual setting of the BPVE, where the photocurrent arises primarily in the bulk of a strongly bonded material, the recombination current is likely to be negligible. This is because momentum scattering rates are many orders of magnitude faster than recombination rates in most semiconductors and insulators,20 and the momenta of electrons and holes are likely to be randomised before recombination occurs. In isolated or weakly bonded systems far from the bulk limit, this assumption may not apply. For instance, in an isolated polar diatomic molecule, only geminate recombination is present. However, as we show below (see the section ‘Delocalised electronic states’), we are often interested in the opposite limit of strongly delocalised electronic states, as these tend to give the largest shift current density. We note that momentum relaxation has the effect of homogeneous broadening; δ-functions are replaced by Lorentzians in equation (7), but the shift current magnitude is not expected to change.

Material properties conducive to shift current response

Polarisation

As we have seen above, the breaking of inversion symmetry is necessary for the shift current response. Materials with broken inversion symmetry can either be polar or non-polar, and this has implications for the type of shift current response in these materials. As an example, consider the non-polar non-centrosymmetric material hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN). Unpolarised light with wavevector incident normal to the h-BN plane does not break the threefold symmetry of the h-BN lattice. In this situation, there is zero net shift current in the h-BN plane.35 Therefore, to exhibit shift current under unpolarised light, polar non-centrosymmetric materials are required. Král has proposed removing the threefold symmetry of h-BN by rolling a flat h-BN sheet into a cylindrical nanotube.35 Such a structure can host a nonzero shift current in the presence of unpolarised light. Depending on the chirality of the nanotube, the shift current can have components along the length of the nanotube, as well as around the circumference of the nanotube. It is possible to study the relationship between the magnitude of the polarisation and the strength of the shift current response in this system by tuning the on-site potential difference between the boron and nitrogen sites in a tight-binding model. At small values of polarisation, the magnitude of the shift vector scales linearly with the polarisation, but the dependence becomes sublinear at higher values of polarisation.

The relationship between shift current response and polarisation is less straightforward in more complex materials. The shift current response of PbTiO3 was calculated using first-principles methods in ref. 22. The polarisation can be changed in the calculation by rigidly displacing the oxygen ions along a single Cartesian axis. The results reveal a complex relationship between the oxygen ion displacement and the shift current (Figure 2). At certain frequencies, an increase of the polarisation causes the shift current to first decrease in the magnitude and then reverse in the direction, whereas at other frequencies, the shift current response is relatively insensitive to the polarisation. Furthermore, a comparison with a related oxide perovskite BaTiO3 shows that despite PbTiO3 having more than twice the polarisation of BaTiO3, both materials exhibit a similar shift current response.22 Therefore, although polarisation is necessary for the shift current response under unpolarised light, a larger polarisation does not always imply a larger shift current response. In equation (7), there is not an explicit dependence of the shift current on material polarisation. Rather, the correlations between shift current and material polarisation arise from how each depends on the breaking of inversion symmetry.

(a) The k-integrated shift vector for PbTiO3 with different polarisation obtained by displacing all oxygen ions along a single axis by 0.01–0.09 of the lattice constant. (b) For oxygen sublattice displacements of 0.01 and 0.09 in PbTiO3, the electronic band structure is shown with one band-to-band transition highlighted that has a large shift vector. Valence and conduction band Bloch wavefunctions for this transition are inset, showing delocalised orbital character along the direction of current flow. Reproduced with permission from ref. 22.

Bonding character

In addition to polarisation, the type of bonding in a system can also affect the magnitude of the shift current response. To understand these effects, we construct a simple one-dimensional tight-binding model36 based on the Su–Shrieffer–Heeger model used in the study of conducting polymers.37 The tight-binding Hamiltonian is

This Hamiltonian describes a one-dimensional chain of orbitals (Figure 3) with alternating on-site energies +Δ and −Δ. In addition, the bonds between the two inequivalent orbitals are alternating with strengths t+δ and t−δ. The parameter Δ controls the site asymmetry of the model, whereas the parameter δ controls the bonding character.

(a) Tight-binding model used in the text, consisting of two inequivalent sites A and B, with on-site energies ±Δ and hopping parameters ±δ. (b) The shift current response of the tight-binding model used in the text. The shift current is shown as a function of the hopping asymmetry and the on-site energy asymmetry. Negative values of shift current (red) correspond to a current flowing to the left in a, and positive values of shift current (blue) correspond to a current flowing to the right in a.

We have calculated the shift current response of this tight-binding model, and the results are displayed in Figure 3b. In the (δ, Δ) parameter space, the lines δ=0 and Δ=0 describe systems with no bond asymmetry and with no on-site energy asymmetry, respectively. The model has inversion symmetry in either of these cases, and the shift current vanishes at these lines. Away from these lines of high symmetry, a change in the sign of either Δ or δ changes the direction of the shift current. This is because changing the sign of Δ applies a bond-centred inversion operation to the system, while changing the sign of δ applies a site-centred inversion operation. At a given value of Δ and δ, the direction of the shift current is dictated by the movement of electrons between sites A and B upon excitation. In ref. 38, explicit formulas are given for the bandedge shift current response of this one-dimensional inversion-breaking model.

When t is set to 0, adjacent bonds have hopping integrals of different sign. In the context of the Slater–Koster tight-binding scheme, this can be interpreted as the orbitals A and B having different orbital characters. For example, if the A and B sites were s and p orbitals respectively, the spσ bonds between them would have hopping integrals of alternating sign. An increase in the magnitude of δ increases the magnitude of the shift current (Figure 3). This suggests that larger bond asymmetries tend to result in higher shift current responses. On the other hand, the site asymmetry parameter Δ is not well correlated with the shift current magnitude (Figure 3b). This is consistent with the general observation made in the previous section that there does not seem to be a simple relationship between polarisation and shift current.

Delocalised electronic states

In this section, and in ref. 36 (SMY and AMR, unpublished data), the tight-binding model of the section ‘Bonding character’ is extended by introducing hopping beyond nearest neighbours. We let the higher-order hopping amplitudes decay exponentially with distance by parameterising them as , with ξ>0 and Rl a lattice vector. We have found that the magnitude of the shift vector is enhanced significantly by the presence of higher-order hopping, particularly near the Γ point of the Brillouin zone (Figure 4). As the higher-order hopping increases, the bandwidth and band dispersion increase also, particularly at the Γ point. As the wavefunctions therefore become more delocalised with higher-order hopping, this implies a correlation between delocalised electronic states and large shift current. Away from Γ, the wavefunctions pick up a phase that varies rapidly in space, resulting in destructive interference and diminishing the effects of higher-order hopping.

These observations are supported by our density functional theory (DFT) calculation of shift current in PbTiO3.22 We find that large shift current occurs when the states involved in the transition have a strong bonding or anti-bonding character along the Ti–O chains collinear with the direction of polarisation. On the other hand, non-bonding states, such as those comprising only oxygen or titanium orbitals, have a weaker shift current response. Heuristically, current-carrying excited states are more likely to be constructed from a superposition of delocalised orbitals rather than heavily localised orbitals.

We have therefore identified two factors that contribute to large shift current response. Promising candidate materials are those with strong covalent bonds that imply highly delocalised states. Wavefunction asymmetry, due either to large atomic displacements from high-symmetry structures or to atomic species with varied orbital characters, will generally increase the shift current response.

Review of experiments

The BPVE in ferroelectric materials has been explored experimentally for >50 years. In many of the older papers on BPVE (e.g., refs 39–41), the measured photocurrents were given different names (optical damage, anomalous PV effect, photogalvanic effect, above-bandgap optical rectification and resonant nonlinear susceptibility), and were only re-interpreted as the shift current42 and referred to as such after the development of the shift current theory. In ferroelectrics, the application of an external electric field is not necessary for the generation of photocurrent, as demonstrated in early work on the prototypical ferroelectric BaTiO3,43 where the photocurrent was attributed to surface space-charge layers. This was followed by studies3,44–47 showing the presence of photocurrents and photovoltages in many other ferroelectrics. The authors of refs 3,47 were the first to propose that the generation of photocarriers in the bulk of a ferroelectric was the direct consequence of the unique axis of polarisation. Further developments include the strong dependence of photocurrent on light polarisation direction in BaTiO3,39 and a giant BPVE in LiNbO3 (ref. 48) scaling linearly with light intensity.

Following the development of the shift current theory,1,21,35 there appeared experiments that discussed the shift current, and in particular, its relation to other nonlinear optical effects. Above-bandgap optical rectification, which was later understood to be dominated by the shift current,42 was measured in GaAs40 and modelled from the perspective of the nonlinear optical susceptibility.41 Experiments on semiconductor quantum wells have distinguished between shift currents and circular photogalvanic currents.49,50 An estimate of the shift vector was extracted by comparing a phenomenological model for shift currents with the experiments on wurtzite semiconductors,51 while a shift current model was used to understand the ultrafast optical response of GaAs.52 In ferroelectrics, a direct comparison of ab initio shift current calculations with experiment has provided support for the shift current theory.22,53 Recently, shift current effects have been studied in the high-field, low-frequency regime,16 whereas the effect of Coulombic interactions on the shift current have also been studied experimentally.17

Shift currents have also been measured in systems other than bulk ferroelectrics, such as GaAs quantum wells and surfaces. Due to the Td symmetry of GaAs, only xyz, zxy, yzx, yxz, zyx and yzx tensor elements are nonzero. Bieler et al.17,54 reported additional nonzero tensor elements of the shift current in semiconductor quantum wells because of symmetry reduction of the quantum well structure. Furthermore, this quantum confinement-induced BPVE is also observed recently in ferroelectric heterojunctions. Nakamura et al.19 have measured the photocurrent in LaFeO3/SrTiO3 heterojunctions with varying LaFeO3 thickness. This work illustrates the co-existence of the shift current and the drift current (induced by internal electric field) with opposite directions. By manipulating the LaFeO3 layer thickness, the polarisation magnitude can be changed, introducing sign change of the total photocurrent due to the competing contributions of the shift current and the drift current. With the decrease of the system dimensions, the BPVE is also observed in one-dimensional molecules and organic crystals. Ogden and Gookin18 measured the BPVE in a prototypical organic polymer with net electric dipole moment >30 years ago. Recently, Vijayaraghavan et al.55 observed the BPVE of 1,4-diphenylbutadiene crystal with π-conjugated molecules, providing experimental evidence for the BPVE in polar organic crystals.

It was found that BPVE is enhanced in nanostructures.56 For example, (Pb,La)(Zr,Ti)O3 (PLZT) and its solid solutions in a thin-film form can have high photocurrent magnitude. Ichiki et al.57 observed higher BPVE in a crystallographically oriented PZT film than in a randomly oriented film. Qin et al.58 reported that decreasing film thickness is an effective way to engineer BPVE and increase the efficiency markedly, which is further supported by the giant BPVE observed in BaTiO3 thin films.56 Pintilie et al. have measured the short-circuit photocurrent of Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 (PZT) polycrystalline layers and epitaxial films under different light frequencies. The direction of the photocurrent flips when the polarisation of the film is reversed by applying voltage.59,60

Materials with low bandgaps and high polarisations have attracted considerable attention in PV material design. There have been many studies on understanding and optimising the BPVE in BiFeO3 (BFO)34,61–65, because of its relatively low bandgap (2.3–2.8 eV), high polarisation (90 μC/cm2)66 and functional optical properties.67 In particular, the observed large open-circuit voltage34,61,62 suggests its use as a potential PV material. Choi et al.68 reported a diode-like effect in a single-domain BFO crystal, and the direction of the diode is determined by the polarisation of the crystal and can be switched by larger external fields. This ability to switch the BPVE direction in BFO is also supported by measurements of Ji et al.69 on an epitaxial BFO thin film. The photocurrent was observed to flow in the opposite direction of the BFO polarisation, and the current is switchable by switching the polarisation direction. Recently, [KNbO3]1−x [BaNi1/2Nb1/2O3−δ]x (KBNNO) with large bandgap tunability (Eg=1.1–3.8 eV) and spontaneous polarisation was found to generate BPVE photocurrent ~50 times larger than that of the ferroelectric PLZT, suggesting potential applications in PV solar cells.70

As mentioned above, the excellent PV properties of BFO are likely related to its large polarisation and low bandgap compared with other ferroelectrics. However, there are many other factors that affect the BPVE in BFO. Seidel et al.62 observed that domain walls have a critical role in carrier generation and recombination. Including more domain walls gives rise to higher open-circuit photovoltage61 and enhances the photoconductivity of BFO.35 On the other hand, Alexe et al.71 suggested that shallow defect levels in the bandgap of BFO are important. Interestingly, in ref. 69, nonzero BPVE was observed in single-domain BFO perpendicular to the polarisation direction, showing that for various space groups, BPVE need not be along the ferroelectric polarisation direction.68,72,73

The role of defects in the BPVE is also emphasised, showing that oxygen vacancies are important for the electric-field-induced switching PV diode effect74,75 and the photoconductivity.76–78 Furthermore, the BPVE and photo-refractive effect in iron-doped LiNbO3 have been studied for a long time,79–83 demonstrating the significant role of Fe in enhancing the performance. The photo-refractive effect, or ‘optical damage’, is caused by the BPVE without electrodes, leading to a space-charge field that changes the refractive index via the electro-optic effect.80 Recently, Cr-doped BFO (including BFO and BiCrO3 solid solutions) has attracted great interest. Nechache et al.84 have observed 6% PCE in Bi2FeCrO6 epitaxial thin films. Moreover, this material shows strong bandgap tunability (as high as 1 eV) by varying the B-site cation ordering and ordered domain size, and ≈8% PCE was reported in a multilayer configuration of this material.85 In these complex materials with dopants and defects, inelastic scattering may have a role in PV response, and other theories besides the shift current may be necessary in these cases.7

Modern materials design for shift current

In this section, we apply shift current design principles to a wide variety of real materials, and study their shift current responses, calculated within the first-principles formalism introduced in the section ‘Theory of the shift current response’.

Polar order engineering

The starting point of shift current materials design is the breaking of inversion symmetry, which is essential for the shift current response. The ferroelectric oxides, with their switchable polar order, are a natural class of materials to consider.

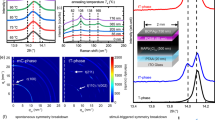

First, we consider the well-known room temperature multiferroic material BFO. In the following, the polarisation direction is taken to be the z direction. The R3c space group of BFO only allows a few nonzero tensor elements for its BPVE responses, which can be computed from first principles using the shift current theory outlined in the section ‘Theory of the shift current response’. To calculate the shift current response, the electronic structure of BFO must first be computed. Young et al. used the DFT+U method along with a semi-core pseudopotential for Fe to improve the description of the 3d electrons and correctly describe the antiferromagnetic physics in this material, giving Eg=2.58 eV. Shown in Figure 5c,b are the yyY components of the Glass coefficient and shift current response tensor σ as a function of light frequency.24 The response occurs at photon energies higher than the bandgap of the bulk. As shown in the spectra, the experimentally measured shift current and Glass coefficient perpendicular to the polarisation63 are in good agreement with calculations. Current in directions perpendicular to the polarisation should not contain contributions directly generated by the polarisation, such as the depolarisation field photocurrent. Therefore, these results establish that the shift current mechanism has a significant role in the BPVE of BFO.

(a) The structure of BFO. The arrow indicates the spontaneous polarisation direction. The cube with cyan dashed lines in the inset graph shows the pseudo cubic unit cell of BFO. (b) Calculated shift current responses (σ) along the Z direction (polarisation direction). Both xxZ and zzZ components of the shift current tensor are shown. (c) Glass coefficient and (d) shift current response (σ) along yyY direction. The dashed lines indicate the experimental measured Glass coefficient and BPVE response. Reproduced with permission from ref. 24.

Besides explaining the BPVE in BFO, the first-principles approach to computing shift current has also successfully explained the BPVE in the prototypical ferroelectrics BaTiO3 (BTO) and PbTiO3 (PTO), and provides further guidelines for designing materials with large BPVE. Shown in Figure 6 is the comparison between experimentally measured I(ω)39 and computed shift current response spectrum for BTO.22 The shaded region indicates the experimental error bars using parameters from the original experiment. The calculated short-circuit photocurrents agree with the measurements very well in terms of both direction and magnitude.

Although materials that are almost non-polar tend to have small shift current responses (see the discussion of hybrid perovskites in the section ‘Wavefunction engineering’), a larger polarisation does not always lead to larger shift currents. To understand the relationship of shift vector and shift current to polarisation, these quantities are calculated while manually moving the atoms to vary the polarisation magnitude. As illustrated in Figure 2a, the dependence of shift vectors on polarisation can be nonlinear. Even the direction of the shift current may not be related to the direction of the bulk polarisation, and the current direction can change as a function of light frequency (Figure 6).

These observations suggest that the material polarisation does not determine the shift current magnitude and direction. Instead, there are other factors related to the electronic structure of the materials which strongly affect shift current magnitudes. These will be analysed in the following sections.

Electronic structure engineering

In this section, we examine electronic structure design principles for high shift current responses: (1) engineering delocalised orbital characters using s and p orbitals; (2) the need for an appropriate bandgap in the visible light region; (3) attaining high density of states using materials with low-dimensional components.

Wavefunction engineering

The tight-binding results of the section ‘Delocalised electronic states’ suggest that delocalised electronic states are beneficial for large shift currents, as they are more likely to support current-carrying excited states. In PTO, DFT calculations22 show that states with delocalised character tend to give high shift current responses (Figure 2b), whereas non-bonding or strongly localised states tend to give low shift current. Transitions involving bands with strong contributions from transition metals with localised d orbitals tend to have small shift vectors.

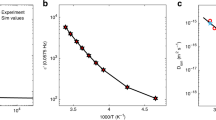

A family of materials with strong s and p orbital characters in the valence and conduction bands is the organometal-halide perovskites (OMHPs). They have attracted huge interest due to their rapidly increasing PCE. Appropriate bandgaps within the visible light range,86 long carrier lifetime,87 and strong light absorption88 make these materials promising for PV solar cells. To illustrate the above ideas about wavefunction delocalisation, we consider the most studied OMHP—CH3NH3PbI3 (MAPbI3), which has a dipolar molecular cation at each A-site.89 We consider configurations of MAPbI3 that break inversion symmetry and thereby allow BPVE.

The valence bands MAPbI3 are primarily of Pb 6s and I 5p characters,90 which is reminiscent of the simplified tight-binding model introduced in the section ‘Bonding character’. The shift current response in MAPbI3 has been computed,27 including spin–orbit coupling,90–92 in two types of structures: one with all the molecular dipole moments aligned (M1) and another in which all the molecular dipole moments nearly cancel with neighboruing molecules (M2). The nearly non-polar M2 structure has a much smaller shift current response than M1 (Figure 7). The importance of the strongly delocalised states involved in the photo-transitions in MAPbI3 is demonstrated by the fact that MAPbI3 has a shift current magnitude comparable to that of BFO, despite having a much smaller polarisation (≈5 μC/cm2 in the z direction) than BFO (≈100 μC/cm2).

(a) Shift current responses of hybrid perovskite CH3NH3PbI3 in two cases, when the molecular dipole moments are aligned parallel (M1) or aligned opposite to neighbours (M2). Both spin–orbit coupling (SOC) and non-SOC (NSOC) are considered due to the presence of heavy atoms (such as Pb and I). (b) Glass coefficient of M1 and M2 cases. M1 (polar) shows significantly enhanced BPVE response compared to M2 (non-polar). Reproduced with permission from ref. 27.

The delocalised nature of the conduction and valance band states in MAPbI3 can be further increased by Cl doping. It was shown that doping Cl at the equatorial positions increases the shift current of the M1 structure, giving an approximately three times larger shift current response than BFO. The equatorial Cl doping results in structural distortions and hybridisation of the conduction band Pb 6px/y orbitals with the halide p orbitals, leaving the Pb 6pz orbitals as the dominant orbital character of the conduction band. As pz is more delocalised in the direction of current (z) than px/y, this results in an enhanced shift current. Experimentally, Cl doping enhances the ordinary PV effect in MAPbI3 greatly, although the origin of this effect is still under debate.93–95

Another materials design strategy in the OMHPs is the substitution of A- and B-site members of the perovskite structure. By introducing Ge on the B-site and having both Cs and organic molecules as A-site in OMHPs, the resulting materials show spontaneous polarisation as a consequence of the Ge2+ lone pair, and they exhibit large second-harmonic generation.96 Such a strategy might also hold promise for the shift current response, which, like second-harmonic generation, is a nonlinear optical effect.

Bandgap engineering

It is desirable for the bandgap of a shift current material to lie in the visible spectrum, if it is to be used in solar power light-harvesting devices. In this section, we focus on ways to control the onset of light absorption and shift current generation, using the recently synthesised low bandgap ferroelectric material (K,Ba)(Ni,Nb)O3−δ (KBNNO)70,97,98 as an example.

One method of controlling the bandgap is by introducing site-specific aliovalent substitutions99 and vacancies into the parent material KNbO3.100,101 Oxygen vacancies may have both positive and negative effects on the functional properties of materials. For example, oxygen vacancies are one of the most important providers of n-type carriers, making them beneficial for n-type semiconductors, but O vacancies remove p-type carriers, making them detrimental for p-type semiconductors. For PV and photocatalytic materials, oxygen vacancies are generally detrimental, because they can enhance the charge recombination rate and reduce the mean free path of the charge carriers. Nevertheless, oxygen vacancies can also be incorporated purposefully to reduce conventional mobility (which enhances Voc, equation (1)), to compensate charge, and to induce desired structural changes, as we show here in KBNNO.

In this material, the substitutional defects involve Ni2+ ions replacing Nb5+ ions, Ba2+ ions replacing K+ ions and charge compensation by O vacancies. We consider two structural configurations of (2/3)KNbO3-(1/3)Ba(Ni1/2Nb1/2)O11/4 with two Ni2+ substitutions each. In one configuration (C1 configuration), the two Ni ions are distributed along the body diagonal direction with the O vacancy adjacent to only one Ni2+ ion (NiO6 and NiO5), whereas in the other (C2 configuration), the two Ni ions are aligned along the Cartesian z axis with one O vacancy in between, leaving both Ni2+ an environment of O5 (two NiO5).

Compared with the C2 configuration, the C1 configuration exhibits a larger Glass coefficient and a lower onset photon energy (Figure 8). These two arrangements have very different electronic structure properties. In the C1 arrangement, Nb and Ni orbital-dominated gap states are induced, leading to a smaller bandgap. In the C2 arrangement, these states move deeper into the valence band, and O 2p orbitals dominate the top of the valence band. This difference in the electronic properties is ascribed to their different structural properties. The larger lattice asymmetry corresponding to the NiO5 complex induces a much bigger splitting between the and orbitals and a much lower energy of the orbital than those for the NiO6 complex. As a result, gap states are induced for the C1 arrangement because it also contains NiO6 complexes, but in the C2 arrangement these states do not contribute to the bandedge electronic transitions, as only NiO5 complexes are involved. Therefore, by moving O vacancies away from Ni, the shift current is significantly enhanced and this effect is accomplished through the change of structural and electronic orbital character properties.

The effects of vacancy–aliovalent dopant complex and strain on shift current. (a) The Glass coefficients of the KBNNO solid solutions with two different Ni2+ ion arrangements. C1 and C2 correspond to configurations with the two Ni2+ ions distributed along the body diagonal and the Cartesian direction, respectively, as shown by the atomic structure representations in the inset of a. (b) The Glass coefficient of the KBNNO solid solution (configuration C1) under different in-plane biaxial compressive strains. In a, it shows that when oxygen vacancies are away from the Ni dopant, the shift current can be enhanced significantly. In b, it shows that the in-plane compressive strains reduce shift current. This is because the delocalised electronic orbital compositions are shifted away from bandedges. To enhance shift current by in-plane compressive strains, materials must have delocalised electronic orbital compositions that can be moved to bandedges by these strains.

Strain is another method of controlling the bandgap. It is widely applied via epitaxial growth of thin films in order to achieve desired functional properties, as it can substantially affect the octahedral cage distortions, rotate the polarisation and change the electronic structure of perovskites.102–104 We consider applying in-plane compressive strain to the (2/3)KNbO3-(1/3)Ba(Ni1/2Nb1/2)O11/4 solid solution. The configuration we adopt here includes two Ni atoms at the body diagonal positions (C1). Our results show that compressive strains increase the shift current onset photon energy (Figure 8). A detailed electronic structure and wavefunction analysis indicates that the applied compressive strains drive the original orbital-dominated gap states to shift downwards in energy and finally merge into the valence band.28 This gives rise to a larger band gap and also reduces the magnitude of the shift current response. To make use of the beneficial effect of in-plane compressive strains, materials must have delocalised electronic orbitals that can be shifted to bandedges by these strains.

Apart from defects and strain, other methods are available for tuning the properties of KBNNO. Recently, manipulation of local polar order (potential gradients) has been proposed as a way to control shift current response in solid solutions in this material.30

Density of states engineering

Another approach for increasing shift currents is designing materials with large density of states near the bandedges.38 The shift current responses at frequencies close to the bandgap energy are often the most relevant for large bandgap semiconductors, as they fall in the visible light spectrum. Furthermore, first-principles calculations show that the shift vector is often large near the bandgap. One-dimensional structures have increased joint densities of states near the bandgap energy, magnifying the shift current at this energy. This suggests that low-dimensional materials such as chain- and layer-like structures may be promising materials with large BPVE.

The alkali-metal chalcogenides are a class of materials with this property. Many members of the class, such as KPSe6, K2P2Se6, LiAsSe2, LiAsS2 and NaAsSe2 show bandgaps in visible light region.105 It was also found that some of them show spontaneous polarisation and strong second-harmonic generation responses.105,106 We consider the shift current responses of LiAsSe2, LiAsS2 and NaAsSe2. All three materials have been synthesised in polar monoclinic space group, with Cc for LiAsSe2 and LiAsS2, and Pc for NaAsSe2. Figure 9 shows that these three compounds have one-dimensional As-X chain (X=Se, S) motifs. The orbitals of the states near the bandgap are mainly s and p orbitals coming from P, As or Se, with a strong covalent character.

Shift current response magnitude (zzZ component) of LiAsSe2. The dashed line indicates the response of BFO for comparison. Reproduced with permission from ref. 26. The upper inset displays the atomic structure of LiAsSe2, showing one-dimensional As–Se chains (into the page as shown by the green box), which contribute to the large shift current magnitude. The bottom inset indicates the chain structure in b-c plane.

Shown in Figure 9 is the shift current response spectrum of LiAsSe2, with the dashed line indicating the shift current response of BFO (with a magnitude of σ≈3×10−4 (A/m2)/(W/m2)). Due to the well-known issue of underestimation of band gaps in DFT, the LiAsSe2 spectrum has been shifted to have the experimental bandgap (1.11 eV).24 The zzZ component of LiAsSe2 shift current shows broad and high magnitude, displaying around 50 times larger response than BFO, making it a potential candidate for solar cell materials. LiAsS2 shows similar spectrum line shape to LiAsSe2 but with smaller magnitude. This may be because the bonds between As and S are not as covalent as between As and Se. These results for the alkali-metal chalcogenides suggest that materials with a strong degree of anisotropy and one-dimensional conducting channels can potentially have large shift current responses.

Conclusions and outlook

In this review, we have examined the factors contributing to the shift current response arising from exciting a current-carrying coherent state. The breaking of inversion symmetry is necessary, but there are many other electronic structure factors affecting the shift current magnitude. We have seen that it is desirable to have a bandgap in the visible spectrum, as well as a large density of states at the bandedges to efficiently capture incident light. Once excited, the shift current carriers rapidly propagate to the electrodes via coherent evolution of the current-carrying state. For this purpose, it is beneficial to have highly delocalised conduction or valence band states, to aid in the coherent evolution of the carriers from the bulk of the material to the electrodes. There are many specific materials design approaches that can be used to achieve these requirements, such as substitutional doping, the introduction of vacancies, the application of strain and the use of low-dimensional materials. In addition, it has recently been suggested that the tuning of topological phase transitions29 can enhance the shift current response.

A remaining open question is the calculation of the PCE of a shift current material. The formalism developed in the section ‘Theory of the shift current response’ is useful for calculating the short-circuit current, but the open-circuit voltage, one of the important factors contributing to the PCE, is less amenable to calculation using periodic boundary conditions. Furthermore, the open-circuit voltage depends on factors external to the shift current theory, such as the total conductivity, which is not generally a bulk quantity. A related issue is the effect of electrodes on the measured photocurrent. Careful selection of electrode materials has improved PCE in the linear response regime, and it is likely that a similar effect exists for shift current materials. The study of the temporal shift current response beyond the continuous wave limit,53,107 the topological aspects of nonlinear optics29,108 and the effect of excitons109 have also become interesting directions of research in recent years. It is expected that shift current is preserved in the presence of excitons.109

In summary, the nascent applications of polar materials in PV applications call for a clear understanding of the origin of the BVPE. Understanding and quantifying the interplay between bulk photocurrent, material compositions, nanostructures, strains and structural defects will help to realise the true potential of BVPE. Distinguishing the truly bulk effect from the interfacial effect in ferroelectrics will inspire device engineering guidelines to apply both mechanisms for solar energy conversion. The shift current theory provides a valuable tool to discover, design and optimise materials for BVPE-based devices with first-principles methods. We believe that with concerted experimental and theoretical efforts, the BVPE will find its applications in the PV industry.

References

von Baltz, R. & Kraut, W. Theory of the bulk photovoltaic effect in pure crystals. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5590–5596 (1981).

Auston, D. H., Glass, A. M. & Ballman, A. A. Optical rectification by impurities in polar crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 28, 897–900 (1972).

Glass, A. M., von der Linde, D. & Negran, T. J. High-voltage bulk photovoltaic effect and photorefractive process In LiNbO3 . Appl. Phys. Lett. 25, 233–235 (1974).

Fridkin, V. M. Bulk photovoltaic effect in noncentrosymmetric crystals. Crystallogr. Rep. 46, 654–658 (2001).

Belinicher, V. I. & Sturman, B. I. The photogalvanic effect in media lacking a center of symmetry. Sov. Phys. Usp. 23, 199 (1980).

Butler, K. T., Frost, J. M. & Walsh, A. Ferroelectric materials for solar energy conversion: photoferroics revisited. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 838–848 (2015).

Belinicher, V. I. The relation between shift and ballistic currents in the theory of photogalvanic effect. Ferroelectrics 83, 29–34 (1988).

Deyo, E., Golub, L. E., Ivchenko, E. L. & Spivak, B. Semiclassical theory of the photogalvanic effect in non-centrosymmetric systems. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/0904.1917 (2009).

Moore, J. E. & Orenstein, J. Confinement-induced berry phase and helicity-dependent photocurrents. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 026805 (2010).

Sodemann, I. & Fu, L. Quantum nonlinear hall effect induced by berry curvature dipole in time-reversal invariant materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 216806 (2015).

Ganichev, S. D. et al. Conversion of spin into directed electric current in quantum wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4358–4361 (2001).

Diehl, H. et al. Spin photocurrents in (110)-grown quantum well structures. N. J. Phys. 9, 349 (2007).

Olbrich, P. et al. Observation of the orbital circular photogalvanic effect. Phys. Rev. B 79, 121302 (2009).

Karch, J. et al. Photoexcitation of valley-orbit currents in (111)-oriented silicon metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors. Phys. Rev. B 83, 121312 (2011).

Sturman, B. I. & Fridkin, V. M. The Photovoltaic and Photorefractive Effects in Noncentrosymmetric Materials 8 (Breach Science Publishers, 1992).

Somma, C., Reimann, K., Flytzanis, C., Elsaesser, T. & Woerner, M. High-field terahertz bulk photovoltaic effect in lithium niobate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 146602 (2014).

Bieler, M., Pierz, K., Siegner, U. & Dawson, P. Shift currents from symmetry reduction and Coulomb effects in (110)-orientated GaAs∕Al0.3Ga0.7As quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 76, 161304 (2007).

Ogden, T. R. & Gookin, D. M. Bulk photovoltaic effect in polyvinylidene fluoride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 45, 995–997 (1984).

Nakamura, M. et al. Spontaneous polarization and bulk photovoltaic effect driven by polar discontinuity in LaFeO3/SrTiO3 heterojunctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 156801 (2016).

Král, P. Quantum kinetic theory of shift-current electron pumping in semiconductors. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 12, 4851 (2000).

Sipe, J. E. & Shkrebtii, A. I. Second-order optical response in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 61, 5337–5352 (2000).

Young, S. M. & Rappe, A. M. First principles calculation of the shift current photovoltaic effect in ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 116601 (2012).

Nastos, F. & Sipe, J. E. Optical rectification and current injection in unbiased semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 82, 235204 (2010).

Young, S. M., Zheng, F. & Rappe, A. M. First-principles calculation of the bulk photovoltaic effect in bismuth ferrite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 236601 (2012).

Young, S. M., Zheng, F. & Rappe, A. M. Prediction of a linear spin bulk photovoltaic effect in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 057201–057201 (2013).

Brehm, J. A., Young, S. M., Zheng, F. & Rappe, A. M. First-principles calculation of the bulk photovoltaic effect in the polar compounds LiAsS2, LiAsSe2, and NaAsSe2 . J. Chem. Phys. 141, 204704 (2014).

Zheng, F., Takenaka, H., Wang, F., Koocher, N. Z. & Rappe, A. M. First-principles calculation of the bulk photovoltaic effect in CH3NH3PbI3 and CH3NH3PbI3-xClx . J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 31–37 (2015).

Wang, F. & Rappe, A. M. First-principles calculation of the bulk photovoltaic effect in kNbO3 and (K,Ba)(Ni,Nb)O3-δ . Phys. Rev. B 91, 165124 (2015).

Tan, L. Z. & Rappe, A. M. Enhancement of the bulk photovoltaic effect in topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 237402 (2016).

Wang, F., Young, S. M., Zheng, F., Grinberg, I. & Rappe, A. M. Substantial bulk photovoltaic effect enhancement via nanolayering. Nat. Commun. 7, 10419 (2016).

Nastos, F. & Sipe, J. E. Optical rectification and shift currents in GaAs and GaP response: Below and above the band gap. Phys. Rev. B 74, 035201 (2006).

Shockley, W. & Queisser, H. J. Detailed balance limit of efficiency of p-n junction solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. 32, 510–519 (1961).

Gunter, P. & Micheron, F. Photorefractive effects and photocurrents in KNbO3: Fe. Ferroelectrics 18, 27–38 (1978).

Bhatnagar, A., Roy Chaudhuri, A., Heon Kim, Y., Hesse, D. & Alexe, M. Role of domain walls in the abnormal photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3 . Nat. Commun. 4, 2835-1–2835-8 (2013).

Král, P., Mele, E. J. & Tománek, D. Photogalvanic Effects in Heteropolar Nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 1512–1515 (2000).

Young, S. M. Theory of the Bulk Photovoltaic Effect in Oxides, and First-Principles Computational Design of Materials with Bulk Dirac Points. PhD Dissertation, 1–220 (University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons, 2011).

Su, W. P., Schrieffer, J. R. & Heeger, A. J. Solitons in polyacetylene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 42, 1698–1701 (1979).

Cook, A. M., Fregoso, B. M., Juan, F. & de Moore, J. E. Design principles for shift current photovoltaics. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1507.08677 (2015).

Koch, W. T. H., Munser, R., Ruppel, W. & Wurfel, P. Anomalous Photovoltage In Batio3. Ferroelectrics 13, 305–307 (1976).

Zhang, X.-C., Jin, Y., Yang, K. & Schowalter, L. J. Resonant nonlinear susceptibility near the GaAs band gap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2303–2306 (1992).

Chuang, S. L., Schmitt-Rink, S., Greene, B. I., Saeta, P. N. & Levi, A. F. J. Optical rectification at semiconductor surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 102–105 (1992).

Côté, D., Laman, N. & van Driel, H. M. Rectification and shift currents in GaAs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 905–907 (2002).

Chynoweth, A. G. Surface space-charge layers in barium titanate. Phys. Rev. 102, 705–714 (1956).

Chen, F. S. Optically induced change of refractive indices in LiNbO3 and LiTaO3 . J. Appl. Phys. 40, 3389–3396 (1969).

Grekov, A. A., Malitskaya, M. A., Spitsnya, V. D. & Fridkin, V. M. Photoferroelectric effects in ferroelectric semiconductors of the AVBVICVII type with low-temperature phase changes. Sov. Phys. Crystallogr. 15, 500 (1970).

Fridkin, V., Grekov, A., Ionov, P., Rodin, A., Savchenko, E. & Mikhailina, K. Photoconductivity in certain ferroelectrics. Ferroelectrics 8, 433–435 (1974).

Glass, A. M., Linde, D., von der Auston, D. H. & Negran, T. J. Excited state polarization, bulk photovoltaic effect and the photorefractive effect in electrically polarized media. J. Electron. Mater. 4, 915–943 (1975).

Dalba, G., Soldo, Y., Rocca, F., Fridkin, V. M. & Sainctavit, P. Giant bulk photovoltaic effect under linearly polarized x-ray synchrotron-radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 988–991 (1995).

Ganichev, S. D. et al. Removal of spin degeneracy in p-SiGe quantum wells demonstrated by spin photocurrents. Phys. Rev. B 66, 075328 (2002).

Bieler, M., Pierz, K. & Siegner, U. Simultaneous generation of shift and injection currents in (110)-grown GaAs/AlGaAs quantum wells. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 083710 (2006).

Laman, N., Bieler, M. & van Driel, H. M. Ultrafast shift and injection currents observed in wurtzite semiconductors via emitted terahertz radiation. J. Appl. Phys. 98, 103507 (2005).

Kohli, K. K., Mertens, J., Bieler, M. & Chatterjee, S. Pulse-shaper-assisted coherent control of shift currents. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 28, 470–474 (2011).

Daranciang, D. et al. Ultrafast photovoltaic response in ferroelectric nanolayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 087601-1-6 (2012).

Bieler, M., Laman, N., van Driel, H. M. & Smirl, A. L. Ultrafast spin-polarized electrical currents injected in a strained zinc blende semiconductor by single color pulses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 061102 (2005).

Vijayaraghavan, R. K. et al. Bulk photovoltaic effect in an organic polar crystal. Chem. Commun. 50, 6530–6533 (2014).

Zenkevich, A., Matveyev, Y., Maksimova, K., Gaynutdinov, R., Tolstikhina, A. & Fridkin, V. Giant bulk photovoltaic effect in thin ferroelectric BaTiO3 films. Phys. Rev. B 90, 161409 (2014).

Ichiki, M. et al. Photovoltaic properties of (Pb,La)(Zr,Ti)O3 films with different crystallographic orientations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 222903–1–3 (2005).

Qin, M., Yao, K. & Liang, Y. C. High efficient photovoltaics in nanoscaled ferroelectric thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 122904–1–3 (2008).

Pintilie, L., Vrejoiu, I., Le Rhun, G. & Alexe, M. Short-circuit photocurrent in epitaxial lead zirconate-titanate thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 101, 064109–1–8 (2007).

Pintilie, L., Stancu, V., Vasile, E. & Pintilie, I. About the complex relation between short-circuit photocurrent, imprint and polarization in ferroelectric thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 107, 114111 (2010).

Yang, S. et al. Above-bandgap voltages from ferreoelectric photovoltaic devices. Nat. Nano 5, 143–147 (2010).

Seidel, J. et al. Efficient Photovoltaic Current Generation at Ferroelectric Domain Walls. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 126805 (2011).

Ji, W., Yao, K. & Liang, Y. C. Evidence of bulk photovoltaic effect and large tensor coefficient in ferroelectric BiFeO3 thin films. Phys. Rev. B 84, 094115 (2011).

Alexe, M. & Hesse, D. Tip-enhanced photovoltaic effects in bismuth ferrite. Nat. Commun. 2, 256 (2011).

Yang, S. Y. et al. Photovoltaic effects in BiFeO3 . Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 062909–1–3 (2009).

Catalan, G. & Scott, J. F. Physics and applications of bismuth ferrite. Adv. Mater. 21, 2463–2485 (2009).

Kundys, B., Viret, M., Colson, D. & Kundys, D. O. Light-induced size changes in BiFeO3 crystals. Nat. Mater. 9, 803–805 (2010).

Choi, T., Lee, S., Choi, Y., Kiryukhin, V. & Cheong, S.-W. Switchable ferroelectric diode and photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3 . Science 324, 63–66 (2009).

Ji, W., Yao, K. & Liang, Y. C. Bulk photovoltaic effect at visible wavelength in epitaxial ferroelectric BiFeO(3) thin films. Adv. Mater. 22, 1763 (2010).

Grinberg, I. et al. Perovskites oxides for visible-light-adsorbing ferroelectric and photovoltaic materials. Nature 503, 509–512 (2013).

Alexe, M. Local mapping of generation and recombination lifetime in BiFeO3 single crystals by scanning probe photoinduced transient spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 12, 2193–2198 (2012).

Yuan, G. L. & Wang, J. L. Evidences for the depletion region induced by the polarization of ferroelectric semiconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 252904–1–3 (2009).

Qin, M., Yao, K. & Liang, Y. C. Photovoltaic mechanisms in ferroelectric thin films with the effects of the electrodes and interfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 022912–1–4 (2009).

Yi, H. T., Choi, T., Choi, S. G., Oh, Y. S. & Cheong, S.-W. Mechanism of the switchable photovoltaic effect in ferroelectric BiFeO3 . Adv. Mater. 23, 3403 (2011).

Sung, J. H. et al. Single ferroelectric-domain photovoltaic switch based on lateral BiFeO3 cells. NPG Asia Mater. 5, e38 (2013).

Basu, S. R. et al. Photoconductivity in BiFeO3 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 091905 (2008).

Nonaka, K., Akiyama, M., Hagio, T. & Takase, A. Bulk photovoltaic effect in reduced/Oxidized lead lanthanum titanate zirconate ceramics. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 34, 2344 (1995).

Won, C. J., Park, Y. A., Lee, K. D., Ryu, H. Y. & Hur, N. Diode and photocurrent effect in ferroelectric BaTiO3−δ . J. Appl. Phys. 109, 084108 (2011).

Festl, H. G., Hertel, P., Krätzig, E. & von Baltz, R. Investigations of the photovoltaic tensor in doped LiNbO3 . Phys. Status Solidi 113, 157–164 (1982).

Inoue, R. et al. Enhanced photovoltaic currents in strained Fe-doped LiNbO3 films. Phys. Status Solidi A 212, 2968–2974 (2015).

Peterson, G. E. Control of the susceptibility of lithium niobate to laser-induced refractive index changes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 19, 130 (1971).

Zaldo, C. & Fridkin, V. Bulk photovoltaic effect of LiNbO3:Fe in the liquid-he temperature range. Ferroelectr. Lett. Sect. 18, 17–21 (1994).

Fridkin, V. et al. The bulk photovoltaic effect in LiNbO3, crystals under x-ray synchrotron radiation. Ferroelectr. Lett. Sect. 16, 1–5 (1993).

Nechache, R. et al. Photovoltaic properties of Bi2FeCrO6 epitaxial thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 202902 (2011).

Nechache, R. et al. Bandgap tuning of multiferroic oxide solar cells. Nat. Photon. 9, 61–67 (2014).

Stoumpos, C. C., Malliakas, C. D. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Semiconducting Tin and Lead iodide perovskites with organic cations: phase transitions, high mobilities, and near-infrared photoluminescent properties. Inorg. Chem. 52, 9019–9038 (2013).

Stranks, S. D. et al. Electron-hole diffusion lengths exceeding 1 micrometer in an organometal trihalide perovskite absorber. Science 342, 341–344 (2013).

Green, M. A., Ho-Baillie, A. & Snaith, H. J. The emergence of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Photon. 8, 506–514 (2014).

Weller, M. T., Weber, O. J., Henry, P. F., Di Pumpo, A. M. & Hansen, T. C. Complete structure and cation orientation in the perovskite photovoltaic methylammonium lead iodide between 100 and 352 K. Chem. Commun. 51, 4180–4183 (2015).

Even, J., Pedesseau, L., Jancu, J.-M. & Katan, C. Importance of spin-orbit coupling in hybrid organic/inorganic perovskites for photovoltaic applications. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 2999–3005 (2013).

Umari, P., Mosconi, E. & De Angelis, F. Relativistic GW calculations on CH3NH3PbI3 and CH3NH3SnI3 perovskites for solar cell applications. Sci. Rep. 4, 4467 (2014).

Zheng, F., Tan, L. Z., Liu, S. & Rappe, A. M. Rashba spin-orbit coupling enhanced carrier lifetime in CH3NH3PbI3 . Nano Lett. 15, 7794–7800 (2015).

deQuilettes, D. W. et al. Impact of microstructure on local carrier lifetime in perovskite solar cells. Science 348, 683–686 (2015).

Lee, M. M., Teuscher, J., Miyasaka, T., Murakami, T. N. & Snaith, H. J. Efficient hybrid solar cells based on meso-superstructured organometal halide perovskites. Sci. 338, 643–647 (2012).

Colella, S. et al. Elusive presence of chloride in mixed halide perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 3532–3538 (2014).

Stoumpos, C. C. et al. Hybrid germanium iodide perovskite semiconductors: active lone pairs, structural distortions, direct and indirect energy gaps, and strong nonlinear optical properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6804–6819 (2015).

Zhou, W., Deng, H., Yang, P. & Chu, J. Structural phase transition, narrow band gap, and room-temperature ferromagnetism in [KNbO3]1-x[BaNi1/2Nb1/2O3]x ferroelectrics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 111904 (2014).

Zhou, W., Deng, H., Yang, P. & Chu, J. Investigation of microstructural and optical properties of (K,Ba)(Ni,Nb)O3 thin films fabricated by pulsed laser deposition. Mater. Lett. 181, 178–181 (2016).

Choi, W. S. et al. Wide bandgap tunability in complex transition metal oxides by site-specific substitution. Nat. Commun. 3, 689 (2012).

Flückiger, U. & Arend, H. On the preparation of pure, doped and reduced KNbO3 single crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 43, 406–416 (1978).

Xue, D. & Siyuan, P. Z. Chemical bond and nonlinear optical effects of crystals. J. Shanghai Univ. 3, 172–174 (1999).

Fu, H. & Cohen, R. E. Polarization rotation mechanism for ultrahigh electromechanical response in single-crystal piezoelectrics. Nature 402, 281–283 (2000).

Wang, F., Grinberg, I. & Rappe, A. M. Band gap engineering strategy via polarization rotation in perovskite ferroelectrics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 152903 (2014).

Kou, L., Zhang, Y., Li, C., Guo, W. & Chen, C. Local-strain-induced charge carrier separation and electronic structure modulation in zigzag zno nanotubes: role of built-in polarization electric field. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 2381–2385 (2011).

Bera, T. K. et al. Soluble semiconductors AAsSe2 (A=Li, Na) with a direct-band-gap and strong second harmonic generation: a combined experimental and theoretical study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 3484–3495 (2010).

Song, J.-H., Freeman, A. J., Bera, T. K., Chung, I. & Kanatzidis, M. G. First-principles prediction of an enhanced optical second-harmonic susceptibility of low-dimensional alkali-metal chalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 79, 245203 (2009).

Priyadarshi, S., Pierz, K. & Bieler, M. All-optically induced ultrafast photocurrents: beyond the instantaneous coherent response. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 216601 (2012).

Morimoto, T. & Nagaosa, N. Topological nature of nonlinear optical effects in solids. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501524 (2016).

Morimoto, T. & Nagaosa, N. Topological aspects of nonlinear excitonic processes in noncentrosymmetric crystals. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1512.00549 (2015).

Acknowledgements

L.Z.T., F.Z., F.W. and A.M.R. were supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), under grant DE-FG02-07ER46431. S.M.Y. was supported by a National Research Council Research Associateship Award at the US Naval Research Laboratory. S.L. acknowledges the support from the Carnegie Institution for Science. We acknowledge computational support from the NERSC of the DOE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, L., Zheng, F., Young, S. et al. Shift current bulk photovoltaic effect in polar materials—hybrid and oxide perovskites and beyond. npj Comput Mater 2, 16026 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/npjcompumats.2016.26

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npjcompumats.2016.26

This article is cited by

-

Light control with Weyl semimetals

eLight (2023)

-

Visualization of bulk and edge photocurrent flow in anisotropic Weyl semimetals

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Photocurrent as a multiphysics diagnostic of quantum materials

Nature Reviews Physics (2023)

-

Energy conversion and storage via photoinduced polarization change in non-ferroelectric molecular [CoGa] crystals

Nature Communications (2023)

-

General nonlinear Hall current in magnetic insulators beyond the quantum anomalous Hall effect

Nature Communications (2023)