Abstract

Background:

Individuals with exceptional longevity and their offspring have significantly larger high-density lipoprotein concentrations (HDL-C) particle sizes due to the increased homozygosity for the I405V variant in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) gene. In this study, we investigate the association of CETP and HDL-C further to identify novel, independent CETP variants associated with HDL-C in humans.

Methods:

We performed a meta-analysis of HDL-C within the CETP region using 59,432 individuals imputed with 1000 Genomes data. We performed replication in an independent sample of 47,866 individuals and validation was done by Sanger sequencing.

Results:

The meta-analysis of HDL-C within the CETP region identified five independent variants, including an exonic variant and a common intronic insertion. We replicated these 5 variants significantly in an independent sample of 47,866 individuals. Sanger sequencing of the insertion within a single family confirmed segregation of this variant. The strongest reported association between HDL-C and CETP variants, was rs3764261; however, after conditioning on the five novel variants we identified the support for rs3764261 was highly reduced (βunadjusted=3.179 mg/dl (P value=5.25×10−509), βadjusted=0.859 mg/dl (P value=9.51×10−25)), and this finding suggests that these five novel variants may partly explain the association of CETP with HDL-C. Indeed, three of the five novel variants (rs34065661, rs5817082, rs7499892) are independent of rs3764261.

Conclusions:

The causal variants in CETP that account for the association with HDL-C remain unknown. We used studies imputed to the 1000 Genomes reference panel for fine mapping of the CETP region. We identified and validated five variants within this region that may partly account for the association of the known variant (rs3764261), as well as other sources of genetic contribution to HDL-C.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aging is characterized by a deterioration in the maintenance of homeostatic processes over time, leading to functional decline and increased risk for disease and death.1 One of the genes linked to healthy aging and longevity is the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) gene.1,2 Homozygosity in the 405VV variants of CETP is associated with lower concentrations of CETP, higher concentrations of high-density lipoprotein concentrations (HDL-C), and greater HDL-C particle size, all associated with both protection against cardiovascular disease3 and exceptional longevity.4

Functional analyses in mice,5 hamsters,6 and rabbits7 have revealed that the protein encoded by the CETP gene mediates the transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL-C to other lipoproteins such as atherogenic (V)LDL particle and is a key participant in the reverse transport of cholesterol from the periphery to the liver.8 Due to the function of CETP and the association of the gene with HDL-C in humans,9,10 the CETP gene is one of the targets for drug development for dyslipidemia.6,11,12 CETP-inhibition leads to an increase of HDL-C from 30 up to 140% depending on the compound used. The first drug of its class, Torcetrapib was unfortunately associated with an increased mortality and morbidity in patients receiving the CETP inhibitor in addition to atorvastatin.13,14

The estimated heritability of HDL-C levels is high in humans: 47–76%.15–23 Previously published whole-genome sequence data23 reported that common variants (minor allele frequency (MAF)>1%) explain up to 61.8% of the variance in HDL-C levels and that rare variants (MAF<1%) explain an additional 7.8% of the variance. Genome-wide association studies revealed that numerous variants are associated with HDL-C, among which are various common9,10 and rare24,25 variants within the CETP gene in multiple ancestries.4,8,26–28 In this paper, we investigate the association between CETP and HDL-C in humans in further detail to identify variants that are likely to be causal.

To this end, we used a meta-analysis of association studies with imputed genotypes within the CETP region. Our study consisted of data from 59,432 samples, of which the genotypes were imputed to the 1000 Genomes project reference panel (version Phase 1 integrated release v3, April 2012, all populations). By using 1000 Genomes imputed data, we expected to find more rare or low-frequent variants, as well as novel insertions and deletions.

Materials and Methods

Study descriptions

The descriptions of the participating cohorts can be found in the Supplementary Material. All studies were performed with the approval of the local medical ethics committees, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study samples and phenotypes

The total number of individuals in the discovery phase was 59,432 and in the replication phase 47,866. Of the discovery samples, 44,108 individuals (74.21%) were of European ancestry. Of the replication samples, 47,081 individuals (98.36%) were of European ancestry. A summary of the details of both the discovery and replication cohorts participating in this study can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Genotyping and imputations

All cohorts were genotyped using commercially available Affymetrix or Illumina genotyping arrays, or custom Perlegen arrays. Quality control was performed independently for each study. To facilitate meta-analysis and replication, each discovery and replication cohort performed genotype imputation using IMPUTE229 or Minimac30 with reference to the 1000 Genomes project reference panel. The details per cohort can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Association analysis in discovery cohorts

The lipid measurements were adjusted for sex, age, and age2 in all cohorts, and if necessary also for cohort-specific covariates (Supplementary Table 1). Some cohorts included samples using lipid-lowering medication; we did not adjust for lipid-lowering medication in our analysis because HDL-C levels are only minimally influenced by lipid-lowering medication. Each discovery cohort ran association analysis for all variants within the CETP region (chromosome 16, 56.99–57.02 Mbp) with HDL-C.

Meta-analysis of discovery cohorts

The association results of all discovery cohorts for all variants within the CETP region (chromosome 16, 56.99–57.02 Mbp) were combined using inverse-variance weighting as applied by METAL.31 This tool also applies genomic control by automatically correcting the test statistics to account for small amounts of population stratification or unaccounted relatedness and the tool also allows for heterogeneity. We used the following filters for the variants: 0.3<R2 (measurement for the imputation quality)<1.0 and expected minor allele count (expMAC=2×MAF×R2×sample size)>10 prior to meta-analysis. After meta-analysis of all available variants, we excluded the variants that were not present in at least three cohorts, to prevent false positive findings.

Selection of independent variants

To select only variants that were independently associated with HDL-C, we used the Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) tool, version 1.13.32 Although this tool currently supports multiple functionalities, we only used the functions for conditional and joint genome-wide association analysis. This function performs a stepwise selection procedure to select independent single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) associations by a conditional and joint analysis approach. It utilizes summary-level statistics from the meta-analysis and linkage disequilibrium (LD) corrections between SNPs are estimated from the 1000 Genomes (1000G Phase I Integrated Release Version 22 Haplotypes (2010–11 data freeze, 14 February 2012 haplotypes)). GCTA estimates the effective sample size and determines the effect size, the s.e., and the P value from a joint analysis of all the selected SNPs. In this way, we select the best associated variants in CETP. We subsequently checked whether these variants were in LD within the 1000 Genomes reference panel using PLINK33 software (Supplementary Table 3).

Replication of independent CETP variants

Five variants were selected for replication in a sample of 12 independent cohorts: Athero-Express, CHS, FINCAVAS, LBC1936, Lifelines, LLS, NTR-NESDA, PREVEND, PROSPER, QIMR, TRAILS, and YFS. The lipid measurements were adjusted for sex, age, and age2 in all cohorts, and if necessary also for cohort-specific covariates (Supplementary Table 1b). The details per cohort regarding variant genotyping and imputations can be found in Supplementary Table 2. The association results of all replication cohorts were combined and the s.e.-based weights were calculated by METAL.31 Since none of the five variants are in LD (Supplementary Table 3), the Bonferroni-corrected P value for multiple testing was 0.01.

Test previous published results

The meta-analysis of HDL-C as published by Teslovich et al.9 identified 38 genome-wide significant (P value<5×10−8) variants within the CETP region (chromosome 16, 56.99–57.02 Mbp). Within all discovery and replication cohorts, we tested these 38 variants, adjusting for the 5 newly identified independent variants to explore whether the new variants explain previously published results. The association results of all cohorts were combined and the s.e.-based weights were calculated by METAL.31

We used the genotypes of all 1,092 individuals of the 1000 Genomes project to calculate the correlation between the 38 variants. This correlation matrix was used by matSpDlite34 which examines the ratio of observed eigenvalue variance to its theoretical maximum to determine the number of independent variables. For these 38 genome-wide significant variants within the CETP region, the effective number of independent variables is 18 and therefore the experiment-wide significance threshold required to keep type I error rate at 5% is 2.85×10−3.

Conditional analysis of independent CETP variants

The replicated independent variants were selected for conditional analysis in both the discovery and the replication cohorts. In this analysis we adjusted for the lead SNP for this region as reported by Teslovich et al.9 (rs3764261, chromosome 16, position 56,993,324 bp). The association results of all discovery and replication cohorts were combined and the s.e. based weights were calculated by METAL.31 The Bonferroni-corrected P value for multiple testing was 0.01, since none of the five variants is in LD (Supplementary Table 3).

Validation of the new CETP insertion within a family

Within the ERF study, 3,658 individuals have been genotyped on various Illumina (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and Affymetrix chips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA), followed by imputations with MaCH (1.0.18c) and Minimac (minimac-β-14 March 2012) to the 1000 Genomes reference panel. Based on the best guess imputed genotypes, we selected one family in which we expected the insertion to segregate.

Validation of the insertion was performed by Sanger sequencing. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood using standard protocols (salting-out). The intron 2–3 of the CETP gene (Supplementary Table 4) was amplified using PCR and the following primer sequences were used to amplify: forward; 5ʹ-tgggggactcaggtctctcc-3ʹ; reverse; 5ʹ-aaagcacctggcccacaacc-3ʹ; size 409 bp.

PCR reactions was performed in 17.5 μl containing 37.5 ng DNA, 10 pmol/μl of each primer, 2.5 mM dNTPs, 10x PCR buffer with Mg+ (Roche) and 5 U/μl FastStart Taq (Roche Nederland B.V., Woerden, the Netherlands). Cycle conditions: 7 min at 94 °C; 10 cycles of 30-s denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s annealing at 70 –1 °C per cycle and 90-s extension at 72 °C; followed by 20 cycles of 30-s denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s at 60 °C, and 90 s at 72 °C; final extension 10 min at 72 °C. Sephadex G50 (Amersham Biosciences) was used to purify the sequenced PCR products. Direct sequencing of both strands was performed using Big Dye Terminator chemistry version 4 (Applied Biosystems, Bleiswijk, the Netherlands). Fragments were loaded on an ABI3100 automated sequencer and analyzed with DNA Sequencing Analysis (version 5.3) and SeqScape (version 2.6) software (Applied Biosystems). All sequence variants are numbered at the nucleotide levels according to the following references: NC_000016.10:g.56963437_56963438insA (NCBI), NM_000078.2:c.233+313_233+314insA, Human Feb. 2009 (GRCh37/hg19) Assembly.

Results

Meta-analysis in all discovery cohorts to select independent variants

The association of all variants within the CETP region (chromosome 16, 56.99–57.02 Mbp) to HDL-C was tested in all discovery cohorts. These results were combined using the inverse-variance weights as applied by METAL.31 After exclusion of the variants that were not present in at least 3 cohorts, 254 variants remained (Figure 1). A conditional and joint analysis of the 254 variants using GCTA identified 5 independent variants (Figure 2). Three variants were intronic (rs5817082, rs4587963, and rs7499892), one variant was intergenic (rs12920974) and one variant was exonic (rs34065661) (Table 1). Using PLINK software,33 we calculated the LD between the five variants based on the 1000 Genomes reference panel, and found that none are in high LD with each other (Supplementary Table 3).

Forest plots from the discovery meta-analysis results for the five independent variants identified within the CETP region. Only cohorts in which the variants passed QC are included in the forest plot. (a) rs12920974 (chromosome 16, position 56,993,025), (b) rs34065661 (chromosome 16, position 56,995,935), (c) rs5817082 (chromosome 16, position 56,997,349), (d) rs4587963 (chromosome 16, position 56,997,369), and (e) rs7499892 (chromosome 16, position 57,006,590). CETP, cholesteryl ester transfer protein.

Replication of the independent CETP variants

The five independent variants within the CETP region were selected for replication within the following cohorts: Athero-Express, CHS, FINCAVAS, LBC1936, Lifelines, LLS, NTR-NESDA, PREVEND, PROSPER, QIMR, TRAILS, and YFS. Five variants were replicated at a P value of 2.99×10−34 (Figure 3 and Table 2).

Forest plots of the replication meta-analysis for the five independent variants within the CETP region. Only cohorts in which the variants passed QC are included in the forest plot. (a) rs12920974 (chromosome 16, position 56,993,025), (b) rs34065661 (chromosome 16, position 56,995,935), (c) rs5817082 (chromosome 16, position 56,997,349), (d) rs4587963 (chromosome 16, position 56,997,369), and (e) rs7499892 (chromosome 16, position 57,006,590). CETP, cholesteryl ester transfer protein.

Test to explain the previously published results

In each discovery and replication cohort, we tested if the five independent variants explain the associations within the CETP region (chromosome 16, 56.99–57.02 Mbp) as reported in the study by Teslovich et al.9 We tested a total of 38 genome-wide significant (P value<5×10−8) SNPs within this region identified by Teslovich et al.9 and conditioned for the five independent variants in all discovery and replication cohorts. All 38 variants were significantly (P value corrected for multiple testing<2.85×10−3) associated with HDL-C in our joint analyses without adjusting for the 5 independent variants we identified in this work, and 37 (97.37%) were genome-wide significant (P value<5×10−8) despite the fact that our sample size is about 65% of the study by Teslovich et al.9 (Table 3). When conditioning on the 5 variants identified in this work, 27 (71.05%) variants remained significant (P value<2.85×10−3), though the P values were markedly reduced (Table 3). This finding suggests that the new variants we identified may explain in part the previously reported association. Remarkably, the P value of rs3764261 which was reported as the lead SNP for this CETP region by Teslovich et al.9 was highly reduced from 5.25×10−509 to 9.51×10−25 while the β decreased from 3.179 mg/dl to 0.859 mg/dl. This variant is not in LD with any of the five new variants. Due to the lack of LD, the s.e. of rs3764261 does not change much (s.e.unadj=0.066, s.e.adj=0.084), but the effect of rs3764261 does (βunadj=3.179, βadj=0.859) and therefore the χ2 decreases as well, and that results in a higher P value. This indicates that a part of the effect of rs3764261 can be explained by the effect of the five new variants.

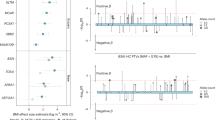

Conditional analysis of the independent CETP variants

Next, we performed conditional analysis of the independent variants in both the discovery and replication cohorts. We conditioned on the lead SNP for the CETP region as reported by the study by Teslovich et al.9 (rs3764261, chromosome 16, position 56,993,324 bp), see Table 4 and Figure 4. This analysis showed that three out of the five variants (rs34065661, rs5817082, rs7499892) are independent of rs3764261. For all variants the P values and β’s decreased, but all P values remained significant. The effect of the single variant rs34065661, of the insertion rs5817082, and of the single variant rs7499892 were reduced by 53.20%, 38.48%, and 32.67%, respectively.

Forest plots of the conditional analysis in the combined discovery and replication cohorts for the five independent variants within the CETP region. Only cohorts in which the variants passed quality control (QC) are included in the forest plot. (a) rs12920974 (chromosome 16, position 56,993,025), (b) rs34065661 (chromosome 16, position 56,995,935), (c) rs5817082 (chromosome 16, position 56,997,349), (d) rs4587963 (chromosome 16, position 56,997,369), and (e) rs7499892 (chromosome 16, position 57,006,590). CETP, cholesteryl ester transfer protein.

Validation of the insertion within a family

We selected based on the best guess imputations of the ERF study, a large family of 30 individuals for Sanger sequencing of rs5817082. Using MERLIN35 we estimated that the total heritability of HDL-C within this family is 27.47%. DNA was available for 16 individuals. Figure 5 shows the results of the Sanger sequencing for rs5817082 for these 16 individuals within the family. The sequencing of the insertion confirmed the best guess results for 10 individuals (62.5%), of which 7 were heterozygous for the insertion, 1 was homozygous for the insertion, and 2 did not carry the insertion. Three individuals that are homozygous for the insertion, were predicted to be heterozygous by the best guess imputations. Three individuals that are heterozygous for the insertion were not predicted to carry the insertion by the best guess imputations. Furthermore, the Sanger sequencing showed that the insertion segregates with the outcome within this family. The proportion of variance explained by the insertion within this family is 35.50%, while the proportion explained by rs3764261, the lead SNP within the CETP region as reported by the study by Teslovich et al.9 is 14.11%.

Discussion

We conducted an analysis to fine map the association between CETP genetic variants and HDL-C. To this end, a total of 59,432 samples were imputed to the latest version of the 1000 Genomes (version Phase 1 integrated release v3, April 2012, all populations). We identified and replicated five independent variants within the CETP region (chromosome 16, 56.99–57.02 Mbp), of which four are SNPs and one is an insertion. We validated the insertion by Sanger sequencing within a large family, as the largest effect on HDL-C comes from this insertion.

The relationship between the CETP gene and HDL-C has been known for a long time9 and genome-wide association studies have revealed many common and rare variants in this region. Although the associated genetic variants are strongly correlated with HDL-C, the causal variants have not been determined. Our study showed that when using the latest 1000 Genomes reference panel, we have more power to fine map this association. By conditional analysis of the five variants, we were able to reduce the P values of the genome-wide significant associations published before by Teslovich et al.9 Furthermore, conditional analysis showed that three out of the five variants are independent of the lead SNP for the CETP region as reported by the study by Teslovich et al.9 (rs3764261).

Several fine-mapping effort have been previously published36,37 and in all those efforts sequencing was used for the fine mapping. In our project we did not use sequencing, but imputations using the 1000 Genomes as a reference panel. This method has been widely used in the past and is much lower in cost. With new reference panels available, we were able to have a revised study of this region. The 1000 Genomes reference panel consists of 30 million variants including a million insertions and deletions. By using this reference panel for imputation, we were able to impute these insertions and deletions in 59,432 samples from various cohorts. This led to the significant association of an insertion within a known region with HDL-C. So far, no association between a structural variation and HDL-C has been found in such a large sample size. Validation of the insertion by Sanger sequencing confirms the correct imputations of this insertion in 62.5% of the individuals, of which seven heterozygous carriers, one homozygous carrier and two did not carry the insertion.

The results of this study showed that by using the 1000 Genomes reference panel, the proportion of the variance explained can be increased and that multiple common variants in the same region may be implicated in a single family of the ERF study. The insertion we identified in this study explains 35.50% of variation in the HDL-C level in a single family of the ERF study; this is in concordance with the results of the whole-genome sequence data.23 This is much higher than the proportion of the variance explained (14.11%) in the same family by rs3764261, which was reported before as the lead variant of this region. Fine mapping of various associations may help us to unravel the genetic background of various phenotypes.

Although rs3764261 was identified by Teslovich et al.9 to be the lead SNP of this region, other variants are used in clinical settings. Three of the classical variants are located in the promoter region of the CETP gene: −1337C/T (rs708272 or Taq1B), −971G/A, and −629C/A (rs1800775) polymorphisms.38 Carriers of the B2 allele of the common Taq1B polymorphism exhibit lower plasma CETP levels and higher HDL-C. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis showed that the B2 allele is associated with a reduced risk for coronary heart disease.39 One more classical variant is rs5882A (405I/V), which is located outside the promoter region.40 The −1337C/T and −629C/A are in strong LD, however, they are in very low LD (r2 of 0.442 for rs708272 and 0.461 for rs1800775) with rs3764261, despite the fact that all three variant are within 3,000 bp of each other.

Large HDL-C particle sizes have been associated with exceptional longevity before and with an increased homozygosity for the I405V variant within the CETP gene.1–4 Many of the studies confirm this relationship, however, all are based on genotyping of the I405V variant. Our study, however, shows that more variants within the CETP gene are associated with HDL-C levels in the blood circulation. Therefore we would suggest investigating more variants within the CETP gene for its association with longevity and healthy aging.

Some genetic variants identified in our study were published before,41,42 but so far no conditional analyses have been performed with these variants. Our study suggests that various CETP variants may be relevant for HDL-levels in the blood circulation and that these may have a substantial role in the heritability of HDL-C in specific families.

References

Barzilai N, Gabriely I, Atzmon G, Suh Y, Rothenberg D, Bergman A . Genetic studies reveal the role of the endocrine and metabolic systems in aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95: 4493–4500.

Barzilai N, Huffman DM, Muzumdar RH, Bartke A . The critical role of metabolic pathways in aging. Diabetes 2012; 61: 1315–1322.

Vergani C, Lucchi T, Caloni M, Ceconi I, Calabresi C, Scurati S et al. I405V polymorphism of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) gene in young and very old people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2006; 43: 213–221.

Barzilai N, Atzmon G, Schechter C, Schaefer EJ, Cupples AL, Lipton R et al. Unique lipoprotein phenotype and genotype associated with exceptional longevity. JAMA 2003; 290: 2030–2040.

Hayek T, Masucci-Magoulas L, Jiang X, Walsh A, Rubin E, Breslow JL et al. Decreased early atherosclerotic lesions in hypertriglyceridemic mice expressing cholesteryl ester transfer protein transgene. J Clin Invest 1995; 96: 2071–2074.

Briand F, Thieblemont Q, Muzotte E, Burr N, Urbain I, Sulpice T et al. Anacetrapib and dalcetrapib differentially alters HDL metabolism and macrophage-to-feces reverse cholesterol transport at similar levels of CETP inhibition in hamsters. Eur J Pharmacol 2014; 740: 135–143.

Kee P, Caiazza D, Rye KA, Barrett PHR, Morehouse LA, Barter PJ . Effect of inhibiting cholesteryl ester transfer protein on the kinetics of high-density lipoprotein cholesteryl ester transport in plasma: in vivo studies in rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006; 26: 884–890.

Zhong S, Sharp DS, Grove JS, Bruce C, Yano K, Curb JD et al. Increased coronary heart disease in Japanese-American men with mutation in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene despite increased HDL levels. J Clin Invest 1996; 97: 2917–2923.

Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 2010; 466: 707–713.

Global Lipids Genetics Consortium, Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, Peloso GM, Gustafsson S et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet 2013; 45: 1274–1283.

Siebel AL, Natoli AK, Yap FYT, Carey AL, Reddy-Luthmoodoo M, Sviridov D et al. Effects of high-density lipoprotein elevation with cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibition on insulin secretion. Circ Res 2013; 113: 167–175.

Remaley AT, Norata GD, Catapano AL . Novel concepts in HDL pharmacology. Cardiovasc Res 2014; 103: 423–428.

Joy TR, Hegele RA . The failure of torcetrapib: what have we learned? Br J Pharmacol 2008; 154: 1379–1381.

Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJP, Komajda M et al. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 2109–2122.

Snieder H, van Doornen LJ, Boomsma DI . Dissecting the genetic architecture of lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins: lessons from twin studies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999; 19: 2826–2834.

Friedlander Y, Kark JD, Stein Y . Biological and environmental sources of variation in plasma lipids and lipoproteins: the Jerusalem Lipid Research Clinic. Hum Hered 1986; 36: 143–153.

Souren NY, Paulussen ADC, Loos RJF, Gielen M, Beunen G, Fagard R et al. Anthropometry, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in the East Flanders Prospective Twin Survey: heritabilities. Diabetologia 2007; 50: 2107–2116.

Sung J, Lee K, Song YM . Heritabilities of the metabolic syndrome phenotypes and related factors in Korean twins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94: 4946–4952.

Almgren P, Lehtovirta M, Isomaa B, Sarelin L, Taskinen MR, Lyssenko V et al. Heritability and familiality of type 2 diabetes and related quantitative traits in the Botnia Study. Diabetologia 2011; 54: 2811–2819.

Vattikuti S, Guo J, Chow CC . Heritability and genetic correlations explained by common SNPs for metabolic syndrome traits. PLoS Genet 2012; 8: e1002637.

Zhou X, Carbonetto P, Stephens M . Polygenic modeling with bayesian sparse linear mixed models. PLoS Genet 2013; 9: e1003264.

Browning SR, Browning BL . Identity-by-descent-based heritability analysis in the Northern Finland Birth Cohort. Hum Genet 2013; 132: 129–138.

Morrison AC, Voorman A, Johnson AD, Liu X, Yu J, Li A et al. Whole-genome sequence-based analysis of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Nat Genet 2013; 45: 899–901.

Peloso GM, Auer PL, Bis JC, Voorman A, Morrison AC, Stitziel NO et al. Association of low-frequency and rare coding-sequence variants with blood lipids and coronary heart disease in 56,000 whites and blacks. Am J Hum Genet 2014; 94: 223–232.

Singaraja RR, Tietjen I, Hovingh GK, Franchini PL, Radomski C, Wong K et al. Identification of four novel genes contributing to familial elevated plasma HDL cholesterol in humans. J Lipid Res 2014; 55: 1693–1701.

Misra A, Shrivastava U . Obesity and dyslipidemia in South Asians. Nutrients 2013; 5: 2708–2733.

Sun L, Hu C, Zheng C, Huang Z, Lv Z, Huang J et al. Gene-gene interaction between CETP and APOE polymorphisms confers higher risk for hypertriglyceridemia in oldest-old Chinese women. Exp Gerontol 2014; 55: 129–133.

Walia GK, Gupta V, Aggarwal A, Asghar M, Dudbridge F, Timpson N et al. Association of common genetic variants with lipid traits in the Indian population. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e101688.

Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J . A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet 2009; 5: e1000529.

Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, calo Abecasis GR . Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 955–959.

Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR . METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 2010; 26: 2190–2191.

Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM . GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet 2011; 88: 76–82.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 559–575.

Li J, Ji L . Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity (Edinb) 2005; 95: 221–227.

Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR . Merlin-rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet 2002; 30: 97–101.

Wu Y, Waite LL, Jackson AU, Sheu WHH, Buyske S, Absher D et al. Trans-ethnic fine-mapping of lipid loci identifies population-specific signals and allelic heterogeneity that increases the trait variance explained. PLoS Genet 2013; 9: e1003379.

Sanna S, Li B, Mulas A, Sidore C, Kang HM, Jackson AU et al. Fine mapping of five loci associated with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol detects variants that double the explained heritability. PLoS Genet 2011; 7: e1002198.

Le Goff W, Guerin M, Nicaud V, Dachet C, Luc G, Arveiler D et al. A novel cholesteryl ester transfer protein promoter polymorphism (−971G/A) associated with plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Interaction with the TaqIB and −629C/A polymorphisms. Atherosclerosis 2002; 161: 269–279.

Boekholdt SM, Sacks FM, Jukema JW, Shepherd J, Freeman DJ, McMahon AD et al. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein TaqIB variant, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, cardiovascular risk, and efficacy of pravastatin treatment: individual patient meta-analysis of 13,677 subjects. Circulation 2005; 111: 278–287.

Peloso GM, Demissie S, Collins D, Mirel DB, Gabriel SB, Cupples LA et al. Common genetic variation in multiple metabolic pathways influences susceptibility to low HDL-cholesterol and coronary heart disease. J Lipid Res 2010; 51: 3524–3532.

Ko A, Cantor RM, Weissglas-Volkov D, Nikkola E, Reddy PMVL, Sinsheimer JS et al. Amerindian-specific regions under positive selection harbour new lipid variants in Latinos. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 3983.

Feitosa MF, Wojczynski MK, Straka R, Kammerer CM, Lee JH, Kraja AT et al. Genetic analysis of long-lived families reveals novel variants influencing high density-lipoprotein cholesterol. Front Genet 2014; 5: 159.

Acknowledgements

We especially thank all volunteers who participated in our study. Further detailed acknowledgements are provided in the Supplementary Material. The funding sources of this project can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

EMvL organized the study and designed the study with substantial input from AI, LAC and CMvD. EMvL drafted the manuscript with substantial input from SSR, CvD, BMP, SWvdL, ST, JAB, JBW, GMP, AS, JVvV, DIB, GD, HS, L-PL, JEH and DEA. All authors had the opportunity to comment on the manuscript. Data collection, GWAS and statistical analysis were done by SWvdL, GP (AEGS); AVS, VG, TBH (AGES); AVS, DEA, ACM, EB (ARIC); JCB, JAB, BMP (CHS); AI, EMvL, CMvD (ERF); MFF, IBB (FamHS); SD, CCW, LAC (FHS); KN, L-PL, MK, TL (FINCAVAS and YFS); HT, SP, BHS (GS); QD, GMP, LAL, JGW (JHS); JEH, CH, IK (CROATIA Korcula); GD, JMS, IJD (LBC1936); JVvV, MAS (Lifelines); JD, AJMdC, PES (LLS); AM, JCM, SSR, JIR (MESA); HM, GW, EJdG, YM, BWJHP, J-JH, DIB (NTR-NESDA); KES, PKJ, JFW (ORCADES); NV, PvdH (PREVEND); ST, IF, BMB, JWJ (PROSPER); GZ, GW, NGM (QIMR); EMvL, MM, CM-G, FR, AGU, AD, OHF, EJS, AH, CMvD (RS); OTR, VV (CROATIA Split); IMN, AJO, HS (TRAILS); PN, AFW, IR (CROATIA Vis); JVvV-O and OTR (YFS). The Sanger sequencing was done by AJMV-V, AALJvO, JMV-D. EMvL performed the meta-analysis and all follow-up steps. Biological association of loci and bioinformatics were carried out by EMvL and CMvD.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

PSM serves on the DSMB of a clinical trial of a device funded by the manufacturer (Zoll LifeCor) and on the Steering Committee of the Yale Open Data Access Project funded by Johnson & Johnson. SWvL is a former employee of Cavadis B.V. GP is a founder and stockholder of Cavadis B.V.

Additional information

A Collaboration between the University Medical Schools and NHS, Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow, UK

See Supplementary Information.

See Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the npj Aging and Mechanisms of Disease website (http://www.nature.com/npjamd)

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

van Leeuwen, E., Huffman, J., Bis, J. et al. Fine mapping the CETP region reveals a common intronic insertion associated to HDL-C. npj Aging Mech Dis 1, 15011 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/npjamd.2015.11

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npjamd.2015.11