Abstract

Noncentrosymmetric conductors are an interesting material platform, with rich spintronic functionalities1,2 and exotic superconducting properties3,4 typically produced in polar systems with Rashba-type spin–orbit interactions5. Polar conductors should also exhibit inherent nonreciprocal transport6,7,8, in which the rightward and leftward currents differ from each other. But such a rectification is difficult to achieve in bulk materials because, unlike the translationally asymmetric p–n junctions, bulk materials are translationally symmetric, making this phenomenon highly nontrivial. Here we report a bulk rectification effect in a three-dimensional Rashba-type polar semiconductor BiTeBr. Experimentally observed nonreciprocal electric signals are quantitatively explained by theoretical calculations based on the Boltzmann equation considering the giant Rashba spin–orbit coupling. The present result offers a microscopic understanding of the bulk rectification effect intrinsic to polar conductors as well as a simple electrical means to estimate the spin–orbit parameter in a variety of noncentrosymmetric systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The effect of the lattice symmetry on the electronic states is a fundamental issue in condensed matter physics. In particular, broken inversion symmetry in the crystal structure generally causes spin band splitting which modifies the electronic ground state, affecting transport properties represented by the superconductivity in noncentrosymmetric systems3,4 or spin-related transport in nonmagnetic materials1,2. Among them, Rashba-5 and Dresselhaus9-type spin–orbit interactions are two well-known textbook models which have succeeded in explaining a variety of exotic phenomena in systems without inversion symmetry.

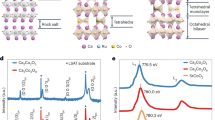

Although the Rashba effect has been conventionally studied at surfaces or interfaces10,11,12,13,14, the recent discovery of three-dimensional (3D) materials which host a large Rashba-type band splitting15,16,17,18 pave the way towards exploring novel transport originating from the 3D chiral spin-texture of the electronic band. BiTeX (X = I, Br) is one such bulk polar semiconductor, in which Bi, Te and X layers are stacked alternately so that the mirror symmetry along the c axis is broken (Fig. 1a). The resultant Rashba-type spin splitting of the electronic bands has been confirmed by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES)15,16 and the transport signatures of the split Fermi surface have been reported by quantum oscillations in resistance19 or thermoelectric coefficients20. However, characteristic magneto-transport reflecting the spin polarization in the electronic band or polarity of the crystal has been elusive, except for photocurrent experiments on BiTeBr21. One of the manifestations of lattice symmetry breaking in electric transport is the rectification effect. In the presence of an in-plane magnetic field, the Rashba-type spin band splitting is modulated to become asymmetric along a direction perpendicular to both the polar axis and the magnetic field (Fig. 1b). Reflecting this asymmetric nature of the electronic band structure, the electrical resistivity is expected to be different, depending on the current direction, as illustrated in Fig. 1c. Although there have been several reports of such an asymmetric electric transport at interfaces6,7,8 or in chiral nanostructures22,23, only one bulk material with chirality is known to show such a nonreciprocity24. In addition, the microscopic mechanism underlying the observed nonreciprocal electric transport is unclear, so that a strategy to enhance this rectification effect is still lacking.

a, Crystal structure of BiTeBr. Bi, Te and Br layers are stacked along the c axis, breaking the mirror symmetry along the stacking direction. b, Rashba-type band structure in kx–ky space under an in-plane magnetic field. Two Fermi surfaces shift along the direction perpendicular to both the polar axis and the magnetic field. Note that the orange arrow represents the direction of polarity in real space. c, Top: atomic force microscope (AFM) image of the measured sample. Micro-size devices were fabricated to obtain single polar domains. Bottom: schematic of the rectification effect in polar systems. When the magnetic field B is applied perpendicular to both the current I and polar axis, the electric resistance is expected to be different, depending on the current direction.  is the a.c. input current with frequency ω, and

is the a.c. input current with frequency ω, and  is the a.c. voltage signal with frequency 2ω.

is the a.c. voltage signal with frequency 2ω.

In this letter, we report the observation of nonreciprocal electric charge transport in polar bulk materials. The rectification effect in BiTeBr satisfies the characteristic selection rule for polar systems, and the magnitude of the signal is greatly enhanced compared with those observed at nonmagnetic interfaces or in chiral materials, reflecting the giant spin splitting. Moreover, the experimental results are quantitatively explained on the basis of a simple Rashba model making use of the Boltzmann equation, indicating that nonreciprocal transport measurements can become a new probe with which to estimate Rashba spin splitting. Our result offers not only a new functionality, in terms of the 3D Rashba system, but also the first quantitative explanation for nonreciprocal electric transport in terms of a microscopic mechanism.

To perform transport experiments in single polar domains, we have fabricated micro-size devices of BiTeBr (as shown in Fig. 1c). Figure 2a shows the temperature dependence of the resistivity of a measured sample. The observed magnitude of the resistivity (ρ ∼ 1 mΩ cm) and carrier density estimated by the Hall effect (n = 1.1 × 1019 cm−3) are similar to those in a previous report21. We have studied the rectification effect in this sample due to the symmetry breaking of the lattice—that is, the difference in the electric resistance depending on the current direction. Electrical resistance is phenomenologically described as

up to second-order terms6,22, where R0, I, β and B represent the resistance at zero magnetic field, electric current, coefficient of the normal magnetoresistance and external magnetic field, respectively. The second term on the right-hand side denotes the normal magnetoresistance, whereas the third term which depends on both the electric current and magnetic field corresponds to the nonreciprocal resistance. The coefficient tensor γ, which describes the ratio of nonreciprocal resistance to the normal resistance, satisfies the characteristic selection rule reflecting the lattice symmetry. For example, γ = 0 in centrosymmetric systems, which means the rectification effect is absent if the crystal has inversion symmetry. On the other hand, γ is finite when the magnetic field, electric current and polar axis are perpendicular to each other in the case of polar systems (Fig. 1c). When the electric current flows along the x axis and the magnetic field is applied along the in-plane direction, the nonreciprocal resistance can be written as

with the polarization P (∥ z) and angle θ between the y axis and the magnetic field (Fig. 2c inset). This current-dependent resistance leads to a nonlinear voltage drop that can be detected as the second-harmonic signal in lock-in measurements. If we apply an a.c. input current (I = I0 sinωt), considering the above selection rule, the nonlinear voltage due to the nonreciprocal components can be expressed as follows:

During the measurement, we have measured a y-component of the second-harmonic signal with a π/2 phase shift, and confirmed that the x-component of the second harmonic is almost zero. The nonreciprocal magnetoresistance is defined as

Figure 2b shows the second-harmonic signals in the cases of θ = 0° and 90°. Here, we plot ΔR2ω, the antisymmetric components with respect to B, to remove any background signals arising from non-uniformity of the samples. When the magnetic field is parallel to the electric current (θ = 90°), there is no discernible signal in the second harmonic. On the other hand, if the magnetic field and electric current are perpendicular (θ = 0°), a finite nonreciprocal resistance signal proportional to the magnetic field appears. This characteristic selection rule (presence or absence of the nonreciprocal signals depending on the relative angle of the magnetic field and the electric current) is also confirmed by the angle dependence measurement under a magnetic field of 9 T in Fig. 2c. Around θ = 90° or 270°, ΔR2ω = 0, whereas ΔR2ω shows finite negative (or positive) values at θ = 0° (or 180°). The angle dependence of the ΔR2ω signal is fitted well by a cosθ curve, which is consistent with the phenomenological discussion. In addition, the observed ΔR2ω signal increases linearly with the electric current (Fig. 2d). Similar behaviour of the ΔR2ω signals has been observed for all samples measured in the experiments (see Supplementary Information). The estimated value of γ, which characterizes the magnitude of the rectification effect, is γ ∼ 1 A−1 T−1 at the lowest temperature, which is much larger than those reported so far (γ ∼ 10−3 A−1 T−1 for a Bi helix22, γ ∼ 10−2 A−1 T−1 for chiral organic materials24, and γ ∼ 10−1 A−1 T−1 for Si FET interfaces6), possibly reflecting the giant spin splitting in BiTeBr.

a, Temperature (T) dependence of the resistivity (ρ). The carrier density is estimated as n = 1.1 × 1019 cm−3 from the Hall effect (inset). b, Magnetic field dependence of the second-harmonic signals in the a.c. resistance. We plot ΔR2ω, which is antisymmetric with respect to the magnetic field B, to remove any background signals coming from non-uniformity of the samples. The ΔR2ω signal corresponding to the bulk nonreciprocal transport is finite when the magnetic field is perpendicular to the current, whereas it is almost zero in the case where the magnetic field is parallel to the current. c, Angular dependence of ΔR2ω. The ΔR2ω signals under the magnetic field are fitted well by a cosθ curve. d, ΔR2ω signal as a function of the electric current, showing a linear dependence of ΔR2ω on the current.

In Fig. 3, we show the nonreciprocal magnetoresistance for several samples with different carrier densities and their temperature dependences. Since γ is the coefficient of electric current (I0) rather than the current density, and thus depends on the sample size, we have calculated the value of γ′ ≡ γA = γLyLz (where Li (i = x, y, z) is the length of the sample along the i direction and A = LyLz is the cross sectional area of the sample) to compare several samples with different dimensions and theoretical calculations. The nonreciprocal electric signal is significantly large in samples with low carrier densities, and is enhanced at low temperature in all samples. (Note that the carrier density n is estimated experimentally from the Hall coefficient, whereas n determines the position of the chemical potential in the theoretical calculation.) Both the steep increase of γ′ in samples with low carrier densities and its enhancement at low temperature, together with its magnitude, are described well by the theoretical calculation (solid lines) using the simple 3D Rashba model as discussed below.

a, γ′ values at the lowest temperature (T = 2 K) for the measured samples plotted as a function of carrier density. Experimentally obtained values are in quantitative agreement with those from the calculation using the 3D Rashba model, showing the similar enhancement in the low-carrier-density region. b, Temperature dependence of γ′. Nonreciprocal resistance signals show an increase on lowering the temperature, which is also in reasonable agreement with the theory. In both plots, error bars are estimated from the absolute minima and maxima of the data and the error coming from the inhomogeneity of the sample thickness or electrode width.

The bulk conduction band of BiTeX under an in-plane magnetic field is described well by the Rashba Hamiltonian

where we set ℏ = 1, σx, σy, σz are the Pauli matrices, and λ is the magnitude of the spin–orbit interaction (with λ = 3.85 eV Å for BiTeI and λ = 2.00 eV Å for BiTeBr16). The magnetic field By in equation (5) has units of energy, and should be regarded as an abbreviation for gμBBy/2, with g and μB being the g-factor and Bohr magneton, respectively. We set m⊥ = 0.15me and m∥ = 5m⊥ based on the previous density functional theory result25. (me is the electron mass in the vacuum.) The energy dispersion reads as

Here, we first focus on the simple two-dimensional (2D) case by setting kz = 0. The schematic energy dispersion as a function of kx at ky = 0 for By < m⊥λ2 and By > m⊥λ2 is shown in the lower part of Fig. 4a. The position of the chemical potential μ determines the topology of the Fermi surfaces and defines the regions I, I′, II, III of the phase diagram (Fig. 4a). In the case of By < m⊥λ2, which is relevant for BiTeBr, there exist three regions, depending on the chemical potential μ: region I, −By − ((m⊥λ2)/2) < μ < By − ((m⊥λ2)/2); region II, By − ((m⊥λ2)/2) < μ < ((By2)/2m⊥λ2); region III, μ > ((By2)/2m⊥λ2). In region I, there is one Fermi surface which does not enclose the origin. In region II (III), on the other hand, there are two Fermi surfaces with the same (opposite) spin helicity enclosing the origin (see also Supplementary Fig. 3). The calculated nonreciprocal current behaves differently depending on the region.

a, Phase diagram in the By − μ plane for 2D Rashba systems under an in-plane magnetic field. The lower part shows the energy dispersion as a function of kx at ky = 0 for By < m⊥λ2 and By > m⊥λ2, respectively. The topology of the Fermi surfaces depends on the position of the chemical potential μ, which determines each region in the phase diagram. The colour represents the magnitude of γ′ at zero temperature. The same colour coding is used in b,c. (Note that γ′ is originally defined in the small-B limit for analysis of the experimental data, but here we define it for general By values using equation (9).) b,c, γ′ values in the small-By limit as a function of the temperature T and the chemical potential μ for the 2D (b) and 3D (c) Rashba Hamiltonian. In region III, γ′ at the lowest temperature is zero (small) for the 2D (3D) system since the contributions to the nonreciprocal current from the inner and outer Fermi surfaces with opposite spin helicities cancel in the single-relaxation-time approximation.

In region II, the first-order current in the electric field Ex is given by solving the Boltzmann equation with the single-relaxation-time (τ) approximation as

This expression contains only even order terms in the magnetic field By (Jx, 2D(1)(−By) = Jx, 2D(1)(By)) and describes the normal resistance, which is independent of the current direction. On the other hand, the second-order current in Ex of region II is given by

which contains a linear term in By (Jx, 2D(2)(−By) = −Jx, 2D(2)(By)). Differently from the first-order term in equation (7), this second-order current leads to an electrical conductivity which depends on the direction of the electric field, and thus describes the nonreciprocal electric transport. Although it is difficult to obtain analytic solutions in region I, we can neglect it for the present analysis of the experimental results. Note that m⊥λ2 = 75 meV for BiTeBr, and hence only the leftmost regime of Fig. 4a is relevant for analysis of the present experiment because we are interested in the region of low magnetic fields of the order of ∼1 T. However, the nonreciprocal magnetoresistance in Fig. 2b seems to deviate slightly from a straight line. In BiTeBr, the typical energy scale of the Rashba spin–orbit coupling (By = m⊥λ2) is By ∼ 43 T, assuming the same large g-factor (g = 60) as BiTeI26. Thus, the effect of the higher-order term (∝ B3) might appear around 9 T. In addition, the larger By/(m⊥λ2) in Fig. 4a also becomes relevant for systems with weaker Rashba splitting. For example, m⊥λ2 for the (In, Ga)As/(In, Al)As heterostructure is of the order of 5 meV (ref. 11). The nonreciprocal current in region III is zero (small) for the 2D (3D) case in the single-relaxation-time approximation since the inner and outer Fermi surfaces have opposite spin helicities above the band-crossing point, and respond to the magnetic field By so that the contributions to Jx, 2D(2) cancel.

In the theoretical analysis above, we have calculated the current density as a function of the applied electric field; Jx = Jx(1) + Jx(2) = σ1Ex + σ2Ex2 (see Supplementary Information). On the other hand, the experimental observable is the voltage drop as a function of the electric current: Vx = R0Ix(1 + γByIx), and γ is expressed as

where Ix = LyLzJx and Vx = LxEx. Therefore, the τ-dependence of σ2 ∝ τ2 and σ1 ∝ τ indicates that γ is independent of τ. In Fig. 4b, c, we plot the calculated γ′ value for the 2D and 3D cases as a function of both the chemical potential and temperature. (For the 3D calculation, we take into account dispersion along the c-axis, as explained in Supplementary Information.) It is noted that, in both the 2D and 3D cases, γ′ diverges as the electron density approaches zero at the lowest temperature, associated with strong suppression with increasing temperature.

These features as well as the magnitude of γ′ are in good agreement with the experimental results, as shown in Fig. 3a, b. This indicates that the single-τ approximation holds in the parameter region for the present measurements. More importantly, the magnitude of the nonreciprocal electric transport γ′ can be regarded as an intrinsic quantity of the band structure and determined by λ, m⊥ and m∥, irrespective of τ. The situation is similar to the Hall effect, in which the Hall coefficient is determined simply by the carrier density.

We note that spin-related quantities in BiTeBr are also of great interest. Theoretically, the Boltzmann theory can also be applied to the spin current in direction i with the spin polarization α in the present system. Here, v is the group velocity and s is the spin operator. The resultant longitudinal spin current flowing in the x-direction is spin polarized in the y-direction. For region II, that is calculated as

According to this equation, the longitudinal spin current linear in Ex vanishes in the absence of a magnetic field in the single-τ approximation. Note that spin current and spin polarization are different and should be distinguished. (There is actually a finite spin polarization due to the Edelstein effect even without a magnetic field27,28.) Recent works reported the detection of spin polarization or spin-to-charge conversion due to spin-momentum locking at the surface of topological insulators29 or in 2D Rashba systems30,31. In these phenomena, spin scattering at the interface between magnetic and nonmagnetic materials is essential and the observed spin signals are dependent on parameters such as the spin-mixing conductance and the effective relaxation time (spin Hall angle), and thus not directly related to the spin–orbit parameter. On the other hand, the charge rectification effect we have reported in this work corresponds to the second-order term in the charge current (equation (8)), which is different from the signals originating from the spin current. (Note that the spin current proportional to Ex2By is absent.) In contrast to the interface spin-dependent phenomena discussed above, γ′, which characterizes the magnitude of the bulk rectification effect, includes only intrinsic band parameters such as the effective mass and Rashba parameters. Thus, the nonreciprocal magnetoresistance can serve as a new probe with which to estimate the magnitude of spin splitting. Experimental detection of the spin current in equation (10) originating from spin-momentum locking in this material is an important and interesting future problem.

In view of the rich families of noncentrosymmetric conductors, including interface / bulk Rashba systems10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 and surface states of topological insulators29 with similar chiral spin textures, the present result offers a new strategy in the search for the giant rectification effect originating from exotic electronic band structures, as well as in constructing novel functionalities in exotic materials.

Methods

Device fabrication.

Single crystals of BiTeBr were prepared by chemical vapour transport (CVT) with the same conditions as in the previous work21. Powders of Bi2Te3, and BiBr3 were mixed into quartz tubes (φ = 24 mm, L = 150) and the temperature was set to 380 °C in the charge zone and to 230 °C in the growth zone, respectively, for seven days. The BiTeBr crystals obtained were cleaved onto Si/SiO2 substrates using the Scotch-tape method and isolated BiTeBr flakes with thicknesses of tens of nanometres were chosen with the aid of an optical microscope and an atomic force microscope (AFM). After an Ar ion milling treatment on the surfaces, Au (150nm)/Ti (5nm) electrodes were patterned into a Hall bar configuration by a standard e-beam lithography process.

Transport measurements.

All the transport properties were measured in a Quantum Design Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS) with a Horizontal Rotator Probe under a He-purged environment. Both the first- and second-harmonic signals of the a.c. resistance were measured by means of a lock-in amplifier (Stanford Research Systems Model SR830 DSP) at a frequency of 13 Hz. During the a.c. resistance measurements, the phase of the first(second-)harmonic signal was confirmed to be approximately 0 (π/2), which is consistent with the theoretical expectation. All the Rω (or R2ω) signals discussed in the main text are x (or y)-components of the lock-in measurement.

Data availability.

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Awschalom, D. D. & Flatté, M. E. Challenges for semiconductor spintronics. Nat. Phys. 3, 153–159 (2007).

Awschalom, D. D. & Samarth, N. Spintronics without magnetism. Physics 2, 50 (2009).

Bauer, E. & Sigrist, M. Non-centrosymmetric Superconductors: Intruduction and Overview (Springer, 2012).

Gor’kov, L. P. & Rashba, E. I. Superconducting 2D system with lifted spin degeneracy: mixed singlet–triplet state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 037004 (2001).

Rashba, E. I. Properties of semiconductors with an extremum loop. 1. Cyclotron and combinational resonance in a magnetic field perpendicular to the plane of the loop. Sov. Phys. Solid State 2, 1109–1122 (1960).

Rikken, G. L. J. A. & Wyder, P. Magnetoelectric anisotropy in diffusive transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 016601 (2005).

Olejník, K., Novák, V., Wunderlich, J. & Jungwirth, T. Electrical detection of magnetization reversal without auxiliary magnets. Phys. Rev. B 91, 180402 (2015).

Avci, C. O. et al. Unidirectional spin Hall magnetoresistance in ferromagnet/normal metal bilayer. Nat. Phys. 11, 570–575 (2015).

Dresselhaus, G. Spin-orbit coupling effect in zinic blende structures. Phys. Rev. 100, 580–586 (1955).

LaShell, S., McDougall, B. A. & Jensen, E. Spin splitting of Au (111) surface state band observed with angle resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3419–3422 (1996).

Nitta, J., Akazaki, T., Takayanagi, H. & Enoki, T. Gate control of spin-orbit interaction in an inverted In0.53Ga0.47As / In0.52Ga0.48As heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1335–1338 (1997).

Koroteev, Yu. M. et al. Strong spin-orbit splitting on Bi surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 046403 (2004).

Ast, C. R. et al. Giant spin splitting through surface alloying. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 186807 (2007).

Santander-Syro, A. F. et al. Giant spin splitting of two-diminsional electron gas at the surface of SrTiO3 . Nat. Mater. 13, 1085–1090 (2014).

Ishizaka, K. et al. Giant Rashba-type spin splitting in bulk BiTeI. Nat. Mater. 10, 521–526 (2011).

Sakano, M. et al. Strongly spin-orbit coupled two-dimensional electron gas emerging near the surface of polar semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 107204 (2013).

Liebmann, M. et al. Giant Rashba-type spin splitting in ferroelectric GeTe (111). Adv. Mater. 28, 560–565 (2016).

Santos-Cottin, D. et al. Rashba coupling amplification by a staggered crystal field. Nat. Commun. 7, 11258 (2016).

Murakawa, H. et al. Detection of Berry’s phase in a bulk Rashba semiconductor. Science 342, 1490–1493 (2013).

Ideue, T. et al. Thermoelectric probe for Fermi surface topology in the three-dimensional Rashba semiconductor BiTeI. Phys. Rev. B 92, 115144 (2015).

Ogawa, N., Baharamy, M. S., Kaneko, Y. & Tokura, Y. Photocontrol of Dirac electrons in a bulk Rashba semiconductor. Phys. Rev. B 90, 125122 (2014).

Rikken, G. L. J. A., Fölling, J. & Wyder, P. Electrical magnetochiral anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 236602 (2001).

Krstić, V., Roth, S., Burghard, M., Kern, K. & Rikken, G. L. J. A. Magneto-chiral anisotropy in charge transport through single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 11315–11319 (2002).

Pop, F., Auban-Senzier, P., Canadell, E., Rikken, G. L. J. A. & Avarvari, N. Electrical magnetochiral anisotropy in a bulk chiral molecular conductor. Nat. Commun. 5, 3757 (2014).

Lee, J. S. et al. Optical response of relativistic electrons in the polar BiTeI semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 117401 (2011).

Park, J. et al. Spin-chiral bulk Fermi surfaces of BiTeI proven by quantum oscillations. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1306.1747 (2013).

Edelstein, V. M. Spin polarization of conduction electrons induced by electric current in two-dimensional asymmetric electron systems. Solid State Commun. 73, 233–235 (1990).

Inoue, J.-i., Bauer, G. E. W. & Molenkamp, L. W. Diffuse transport and spin accumulation in a Rashba two-dimensional electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 67, 033104 (2003).

Li, C. H. et al. Electrical detection of charge-current-induced spin polarization due to spin-momentum locking in Bi2Se3 . Nat. Nanotech. 9, 218–224 (2014).

Rojas-Sánchez, J. C. et al. Spin-to-charge conversion using Rashba coupling at the interface between non-magnetic materials. Nat. Commun. 4, 2944 (2013).

Lesne, E. et al. Highly efficient and tunable spin-to-charge conversion through Rashba coupling at oxide interfaces. Nat. Mater. 15, 1261–1266 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the following grants: JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (No. JP25000003), MEXT Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up (No. JP15H06133), Murata Science Foundation, MEXT KAKENHI (No. JP24224009, No. JP26103006, No. JP25400317 and No. JP15H05854), and ImPACT Program of Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (Cabinet office, Government of Japan), and Grants-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (Grants No. JP16J08009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.I. and Y.I. conceived and designed the experiments. Y.K. performed the growth and characterization of the bulk samples. T.I., S.K. and S.S. fabricated devices and measured transport properties. K.H. and M.E. performed the theoretical calculations. T.I., K.H., S.K., M.E., Y.T., N.N. and Y.I. led the physical discussions and wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary information (PDF 655 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ideue, T., Hamamoto, K., Koshikawa, S. et al. Bulk rectification effect in a polar semiconductor. Nature Phys 13, 578–583 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4056

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4056

This article is cited by

-

Observation of giant non-reciprocal charge transport from quantum Hall states in a topological insulator

Nature Materials (2024)

-

Nonlinear transport and radio frequency rectification in BiTeBr at room temperature

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Light-induced giant enhancement of nonreciprocal transport at KTaO3-based interfaces

Nature Communications (2024)

-

A correlated ferromagnetic polar metal by design

Nature Materials (2024)

-

Quantum-metric-induced nonlinear transport in a topological antiferromagnet

Nature (2023)