Abstract

Three-dimensional Bi-chalcogenide topological insulators exhibit surface states populated by massless Dirac fermions that are topologically protected from disorder scattering1. Here, we demonstrate that these states can be enhanced or destroyed by strain in the vicinity of grain boundaries on the surface of epitaxial Bi2Se3(0001) thin films. Using scanning tunnelling and transmission electron microscopy, we show that the low-angle tilt grain boundaries in Bi2Se3(0001) films consist of arrays of alternating edge dislocation pairs. Along the boundary, these dislocations introduce periodic in-plane compressive and tensile strains. From tunnelling spectroscopy experiments and first-principles calculations, we find that whereas the energy of the Dirac state shifts in regions under tensile strain, a gap opens in regions under compressive strain, indicative of the destruction of the Dirac states at the surface. These results demonstrate that Dirac states can be tuned by strain at the atomic scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Following the demonstration of topological Dirac states in several classes of topological insulators (TIs; ref. 2), extensive research is now devoted to exploring novel phenomena, including the anomalous Hall effect in magnetically doped TIs (ref. 3), and Majorana fermions at the interface between TIs and superconductors4 for new functionalities such as topologically protected qubits for quantum information processing5. The three-dimensional (3D) TIs Bi2X3 (X = Se, Te) are of particular interest because of their relatively large band gaps and single Dirac cone at the centre of the Brillouin zone6. They also crystallize in a distinct layered structure along the [0001] direction, consisting of covalently bonded –X–Bi–X–Bi–X– quintuple layers (QLs; Supplementary Fig. 1). Because of the weak (van der Waals) bonding between QLs, the bulk band topology of these 3D TIs is predicted to be sensitive to uniform uniaxial strain7,8.

Here, we experimentally demonstrate the tunability of the Dirac states by strain at grain boundaries (GBs) in Bi2Se3(0001) films grown by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE). We use scanning tunnelling and transmission electron microscopy to determine that low-angle (0< θ < 15°) tilt GBs in these films consist of alternating edge dislocation pairs with Burgers vectors  (where a is the in-plane lattice constant), which introduce periodic in-plane compressive and tensile strains along the GBs. By tunnelling spectroscopy and density functional theory calculations, we show that the Dirac states are enhanced under in-plane tensile strain (negative c/a ratio), and destroyed under compressive strain (positive c/a ratio).

(where a is the in-plane lattice constant), which introduce periodic in-plane compressive and tensile strains along the GBs. By tunnelling spectroscopy and density functional theory calculations, we show that the Dirac states are enhanced under in-plane tensile strain (negative c/a ratio), and destroyed under compressive strain (positive c/a ratio).

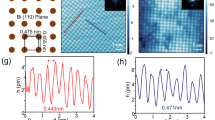

Fig. 1a shows a representative scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) image of the MBE-grown Bi2Se3(0001) films, exhibiting three different types of intrinsic structures as indicated. Although all three types are present independently of film thickness, studied up to 100 nm, their densities vary from 108 to 109cm−2 depending on growth conditions and the substrate used. Facilitated by the intrinsic anisotropic strong intra- and weak inter-layer bonding9, triangular spirals are the most common feature, characterized by atomically smooth terraces, approximately 20–50 nm in width and separated by steps one QL in height, consistent with earlier work10,11,12,13,14.

a, STM image of growth spirals and grain boundaries (GBs) on a 50 nm Bi2Se3 film on SiC(0001) (bias voltage (V s)= 0.56 V, tunnelling current (It)= 0.1 nA). b, STM image of GBs separating three domains (V s= 0.3 V, It= 0.6 nA). c, Fast Fourier transform of the boxed region in b, on the basis of which an angle of 8° is determined between grains 2 and 3. d, Plot of the GB angle distribution. e, Atomic resolution image of a 7° grain boundary (V s=−0.2V,It= 0.4 nA). f, Schematic diagram of the dislocation model of a low-angle GB, where D=b/θ and  (n=4 here).

(n=4 here).

The coalescence of the spirals leads to GBs, appearing as ‘dotted’ lines as a result of periodic height modulation. Neighbouring grains often exhibit in-plane rotation, as evidenced by the formation of moiré patterns. The one marked in Fig. 1a is created by a 7.6° rotation (Supplementary Fig. 2). The angle can be directly determined by fast Fourier transform (FFT) of atomic resolution STM images, such as that shown in Fig. 1b, where three grains meet. The FFT of the boxed region indicates two sets of diffraction patterns, corresponding to a relative rotation of 8°± 1° between domains 2 and 3 (Fig. 1c). Similarly, a rotation of 13°± 1° is found between domains 1 and 3 (not shown). Systematic analysis shows that the majority of the angles are below 8°, with a bi-modal distribution peaked at 7° and 20° for low- and high-angle variants (Fig. 1d).

The origin of the periodic modulation along the GBs is revealed by atomic resolution STM imaging. Away from the GB, a close-packed structure with a spacing of 4.1 Å is observed, characteristic of the (1 × 1) periodicity of Bi2Se3(0001) (Fig. 1e). At the boundary, a Burgers circuit taken around the defect reveals one atom short in the direction perpendicular to the GB, corresponding to a Burgers vector b=a [ ]. Analysis of other low-angle GBs (0< θ < 15°) reveals a similar structure, with the dislocations spaced closer together for larger angles (Supplementary Fig. 3), consistent with the dislocation model of low-angle GBs (Fig. 1f; ref. 15).

]. Analysis of other low-angle GBs (0< θ < 15°) reveals a similar structure, with the dislocations spaced closer together for larger angles (Supplementary Fig. 3), consistent with the dislocation model of low-angle GBs (Fig. 1f; ref. 15).

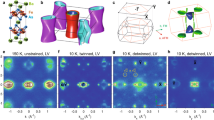

As GBs are planar bulk defects, scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) is ideally suited for the investigation of their atomic structures. The results show that the crystallographic epitaxial relations between the Bi2Se3 films and the SiC(0001) substrate are Bi2Se3(0001)||SiC(0001) and  (Fig. 2a); and Bi2Se3(0001)||SiC(0001) and

(Fig. 2a); and Bi2Se3(0001)||SiC(0001) and  (Fig. 2b). In addition, small deviations in both epitaxial domains are often observed. The case in Fig. 2b shows satellite diffraction spots separated by ± 7°, indicating the presence of a triple domain region within the same epitaxial relationship, consistent with the STM observations (Fig. 1b).

(Fig. 2b). In addition, small deviations in both epitaxial domains are often observed. The case in Fig. 2b shows satellite diffraction spots separated by ± 7°, indicating the presence of a triple domain region within the same epitaxial relationship, consistent with the STM observations (Fig. 1b).

a,b, Selected-area electron diffraction patterns from plan-view high-resolution TEM images of Bi2Se3 grown on graphene/SiC(0001), showing Bi2Se3(0001) grown epitaxially on SiC(0001). SiC diffraction patterns in the [0001] direction are indexed. As a result of double diffraction between the film and substrate, six spots surrounding each Bi2Se3 spot are seen in a and, similarly, triple radial diffraction spots in b. c, HAADF plan-view, and d, Fourier-filtered image of a low-angle (7°) boundary with the location of edge dislocations marked by the yellow and red ‘T’ symbols. e,f, Strain field maps of the HAADF image c obtained by the geometrical phase analysis method as represented by the ɛxx (e) and ɛyy (f) components of the strain tensors. The x axis is taken to be along the boundary and the y axis perpendicular to it.

To determine the atomic structure of these GBs, high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) imaging was carried out, and the results are summarized in Fig. 2c (see also Supplementary Fig. 4). Similar to the STM observations, moiré patterns are often seen near GBs, and periodic strain-induced contrasts are clearly visible along the boundary, with periods similar to those observed in STM for similarly angled GBs (Supplementary Fig. 4b). This is better illustrated in the atomic resolution plan-view image of a low-angle (7°) GB (Fig. 2c), where the positions of the pairs of edge dislocations are also marked by the ‘T’ symbols. Fourier filtered imaging analysis, selectively using only the yellow or red set of the FFT pattern (Fig. 2c inset), suggests that the Burgers vectors for the dislocations are  and

and  , respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). Using both sets of diffraction spots, the Fourier-filtered image obtained (Fig. 2d) closely resembles the HAADF image. These results indicate that low-angle GBs in Bi2Se3(0001) are of the tilt variant15, which is further supported by similar analysis of atomic resolution STM images of a variety of low-angle GBs, where both edge dislocations are also found (Supplementary Fig. 6). This consistent observation using two independent techniques “highlights” the reproducibility of the phenomenon, and confirms the formation of tilt GBs in MBE-grown Bi2Se3(0001) films.

, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). Using both sets of diffraction spots, the Fourier-filtered image obtained (Fig. 2d) closely resembles the HAADF image. These results indicate that low-angle GBs in Bi2Se3(0001) are of the tilt variant15, which is further supported by similar analysis of atomic resolution STM images of a variety of low-angle GBs, where both edge dislocations are also found (Supplementary Fig. 6). This consistent observation using two independent techniques “highlights” the reproducibility of the phenomenon, and confirms the formation of tilt GBs in MBE-grown Bi2Se3(0001) films.

The strain introduced by these dislocations is quantitatively analysed using the geometrical phase analysis (GPA) method16. The strain fields are represented by strain tensor components ɛxx and ɛyy, as shown in Fig. 2e, f, respectively. Clearly associated with each dislocation is a pair of strain fields (in-plane compressive and tensile) that are visible in both the ɛxx and ɛyy maps. They are limited to ∼ 3 nm from each dislocation core with magnitudes up to ±20%, representing lattice distortions of the same magnitude. The in-plane tensile and compressive strains lead to periodic depressions and expansions in the [0001] direction along the boundary as a result of the Poisson effect. This is also seen in other epitaxial systems such as SiGe/Si and III–V semiconductor thin films17,18.

To determine the impact of these lattice distortions in the vicinity of the GBs on the electronic properties of Bi2Se3(0001), density functional theory (DFT) calculations for different out-of-plane strains were carried out. Consistent with earlier calculations7,8, strain can significantly modify the band topology. In particular, for an increase in c/a of ∼4%, the calculated bulk gap vanishes and there is a crossover from a TI to a trivial bulk insulator. Calculations further show that the bulk gap increases with both compression and expansion away from this critical c/a value, and that the position of the Dirac point (for the TI phase) moves within the gap. Close to the critical value, more QLs are required to sustain the formation of the Dirac state: for example, for +3%, which is still within the TI regime, the Dirac surface state becomes gapless only at ∼ 12 QLs, compared to the ∼ 5 QLs required at 0% (ref. 19). This behaviour reflects the fact that more ‘bulk’ is needed near the trivial/topological phase boundary.

The changes in inter-QL separations near the GBs are probably more significant in the first few QLs because of the weak inter-layer bonding. To model this situation, we consider 12-QL films where the inner QLs have the normal c/a and the outer ones are varied. The bands at the surface (which STM is sensitive to) and at the interface between the two regions with different c/a values are shown in Fig. 3a, b, respectively. With in-plane tensile strain (negative c/a), the gap in the surface region increases, and the Dirac point (ED) moves to greater binding energy and slightly up from the top edge of the surface valence band. This leads to the top of the bulk valence band for the −6% actually being above ED at the interface. For in-plane compression (positive c/a), a +3% change results in a decrease of the surface gap, and ED shifts up and away from the valence band. The Dirac state also shifts its weight away from the surface towards the interface. At +6%, where the surface region is nominally a trivial insulator, there is now a gap, and the Dirac state has mostly shifted to the interface. The overall trend in the calculations is that ED shifts to greater binding energy with decreasing c/a, and its position within the gap varies. For increasing c/a ratio, above ∼ 4% (where the material is a trivial insulator), a gap opens at the surface, and the weight of the Dirac state diminishes from the surface and moves to the buried interface.

Calculated layer-dependent Bi2Se3(0001) bands along Γ and ±1/5 K for 3 quintuple layers (QLs) (on each surface) with different c/a ratios on top of 6 QLs with the bulk c/a ratio (a= 4.138 Å, c/a= 2.307). a, Weighted by the localization on the surface QL. b, Weighted by the localization at the interface. The calculated crossover (with the same computational parameters) between the topological and trivial insulating behaviour for bulk Bi2Se3 occurs at a c/a ratio of approximately +4%; the bulk gap increases away from this critical c/a for both compression and expansion.

These predictions are compared with experimental dI/dV tunnelling spectra that measure the surface local density of states at the position of the STM tip. Fig. 4a–c shows an atomic resolution STM image of a 7° GB and its corresponding ɛxx and ɛyy strain maps obtained using the GPA method. The results are similar to the strain analysis of the TEM images, with the strain fields associated with the pair of edge dislocations clearly resolved.

a, STM image of a 7° GB (V s=−0.2 V, It=0.1 nA). b,c, ɛxx (b) and ɛyy (c) strain map of (a) obtained by the geometrical phase analysis method. d, dI/dV spectra taken away from the GB (α), and at bright (β) and dark (γ) regions marked in a. e,f, Spatially resolved dI/dV spectra taken, respectively, across and along the GB at positions marked in a. g, Plot of the experimental Dirac energy shifts as a function of the in-plane rotation (θ) for the low-angle GBs observed in this work.

Three dI/dV spectra were taken at three distinctive regions: α, away from the grain boundary, a strain-free region; β, the bright region, associated with the in-plane compressively strained (blue) regions in the ɛyy map; and γ, the dark region, associated with the in-plane tensile strained (red) regions in the ɛxx map. Away from the GB, the spectrum exhibits a general V-shape, characteristic of as-grown Bi2Se3(0001) (Fig. 4d, spectrum α), with the conductance minimum attributed to electron tunnelling to the Dirac point (ED). Here, ED is at 230 meV below the Fermi level (EF), indicating that the Bi2Se3 film is n-doped, probably as a result of the Se vacancies present in MBE-grown materials20,21. (Note that fluctuations in ED of ±20 meV are typically observed due to variations in growth conditions.) At the bright region of the GB (spectrum β), no single minimum is observed, but a gap of 60 meV appears. At the dark region (spectrum γ), ED reappears, but is shifted to −310 meV.

The spatial evolution of ED and the emergence of the gapare better illustrated by the dI/dV spectra taken at positions along and across the GB. Across the boundary (Fig. 4e), the conductance minimum gradually moves from the nominal −230 meV away from the GB (spectrum 1) to −310 meV (spectrum 7) at the in-plane tensile strained (negative c/a ratio) region of the boundary. Crossing to the opposite side, the conductance minimum reverts gradually back to −230 meV (spectrum 15). The shift of the Dirac point to a more negative value is consistent with the calculations (Fig. 3a). Along the GB (Fig. 4f), however, whereas local minima can also be seen in spectra 4 and 12 at the in-plane tensile-strained (negative c/a ratio) areas, a gap of 60 meV is evident in spectra 1 and 8 at the in-plane compressively strained (positive c/a ratio) regions. The changes in the intensity of tunnelling conductance can be explained by weighted contributions of Dirac states near the dislocations, arising from the spatial variations of the strain fields (Figs 4b, c) and the continuous change of ED with c/a (Fig. 3).

The shifts in ED are measured for a different variety of low-angle GBs, and the results are summarized in Fig. 4g. For rotations in the range of 2°–11°, the shifts are fairly constant, with an average value of 80 ±10 meV. This independence of angle highlights the fact that all low-angle GBs are comprised of the same types of edge dislocations, and differ only in their separations. The values of the shift in Dirac point and gap are in excellent agreement with DFT calculations (Fig. 3). Alternative explanations for these changes in Dirac states may include charged GBs (ref. 22) or topologically protected modes associated with dislocations23,24; however, the gap opening observed here is most consistent with strain-driven evolution of the Dirac states.

Our findings suggest that these local topological changes can impact carrier transport in Bi2Se3. First, the local fluctuations in the Dirac points (ED; for example, Fig. 4) are similar to those induced by charged impurities (that is, dopants) as shown in earlier work25,26. Both are intrinsic to the Bi-based 3D TIs, albeit on different length scales, tens of nanometres for charged impurities and hundreds of nanometres for GBs. These fluctuations can lead to electron and hole puddles, making the charge neutral point challenging to reach26. Transport across GBs can also be affected, similar to graphene. In both cases backscattering is forbidden, owing to time reversal symmetry in Bi2Se3 and the conservation of pseudo spin in graphene. However, scattering at grain boundaries has been shown to increase the electrical resistance in graphene27,28, as well as relate to strain-induced conductance fluctuations29, which can also be expected for Bi2Se3.

Our studies clearly demonstrate the tunability of Dirac states in Bi2Se3 by strain at the atomic scale. This paves the way for strain engineering in layered TIs, for example, by intercalating one atomic layer of zero-valent metals such as Ag to control the van der Waals gap30.

Methods

Molecular beam epitaxy of Bi2Se3 films.

Bi2Se3 films were grown at 275–325 °C on Si-face SiC(0001) prepared by etching in a hydrogen/argon atmosphere at 1,600 °C; and on epitaxial graphene/SiC(0001) by thermal decomposition of SiC at 1,300 °C in ultrahigh vacuum (UHV). For atomic resolution plan-view TEM imaging, graphene grown by chemical vapour deposition (CVD) on Cu foil was first transferred onto a TEM grid, which served as a substrate for the subsequent growth of Bi2Se3. Bi and Se are supplied via separate Knudsen cells heated to 460° and 250 °C, respectively.

The Se/Bi flux ratio and substrate were varied to control the density of spirals and GBs (by varying the interfacial bonding and strain). When Bi2Se3 is grown directly on the Si-face SiC instead of graphene/SiC, the GB density is an order of magnitude larger. In addition, we have shown previously9 that the growth of Bi2Se3 spirals initiates at SiC substrate step edges. On a vicinal substrate, the steps are shown to orientate orthogonally to the miscut direction, which provides a preferred direction for the growth of spirals, and can consequently align the domain boundaries, similar to previous findings11.

Scanning tunnelling microscopy and spectroscopy.

Scanning tunnelling microscopy experiments were performed in an ultrahigh vacuum system with a base pressure below 1×10−10 Torr, which is directly connected to the MBE growth chamber. Electrochemically etched polycrystalline W tips, or mechanically sharpened Pt tips were used to take STM images at room temperature and liquid nitrogen temperature with the bias voltage applied to the tip. dI/dV spectra were acquired using lock-in detection by turning off the feedback loop and applying a small 9 mV (rms) a.c. modulation at 860 Hz to the bias voltage.

Plan-view (scanning) transmission electron microscopy.

Selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) studies of plan-view films were performed using conventional transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Atomic resolution studies of the grain boundary structures were performed on an aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) by high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) imaging. In this method the large-angle elastically scattered electrons are collected by a high-angle annular detector with acceptance angles in the range of 75–170 mrads. Within this angle range, scattered electrons are sensitive to ∼ Z2, thus the contrast in atomic resolution images can be directly interpreted. Owing to the large difference in Z2 between Bi and Se atomic columns, the Se atomic columns are suppressed. Plan-view TEM specimens for SAED analysis were prepared using conventional grinding and polishing methods, followed by low-angle Ar ion milling to achieve electron transparency.

Strain mapping.

Strain mapping was applied to the HAADF plan-view image of a low-angle (7°) grain boundary using geometric phase analysis on the  and

and  Bragg spots shown in Fig. 2c. The size of the filter’s window in Fourier space was set to 30 pixels, corresponding to a spatial resolution of the phase maps equal to 66.548 pixels (or 1.10 nm). Strain maps were calculated at an angle of 101.98° to align the x-axis with the direction of the interface.

Bragg spots shown in Fig. 2c. The size of the filter’s window in Fourier space was set to 30 pixels, corresponding to a spatial resolution of the phase maps equal to 66.548 pixels (or 1.10 nm). Strain maps were calculated at an angle of 101.98° to align the x-axis with the direction of the interface.

Density functional theory calculations.

The relativistic calculations were performed using the full-potential linearized augmented plane wave (FLAPW) method as implemented in flair. The (0001) surface calculations, use 8–14 QLs, with the inter-QL separations defined relative to the separation between the centres of the QLs at the nominal c/a value for bulk Bi2Se3 (a= 4.138Å, c/a=2.307). For the interface calculations, the inner 6 QLs of a 12-QL film were held fixed at the bulk (0%) separations and the outer 3 QLs on each surface were given at the values shown in Fig. 3. The wavefunctions and density/potential cutoffs were 218 and 1,960 eV, respectively, and an 18×18×2k-point mesh was used. The bands shown in Fig. 3 were weighted by their spatial localization in the different regions.

References

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 ( 2010).

Ando, Y. Topological insulator materials. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 82, 102001 ( 2013).

Chang, C-Z. et al. Experimental observation of the quantum anomalous Hall effect in a magnetic topological insulator. Science 340, 167–170 (2013).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Superconducting proximity effect and Majorana fermions at the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407 (2008).

Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Sarma, S. D. Non-abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083–1159 (2008).

Zhang, H. et al. Topological insulators in Bi2Se3, Bi2Te3 and Sb2Te3 with a single Dirac cone on the surface. Nature Phys. 5, 438–442 (2009).

Young, S. M. et al. Theoretical investigation of the evolution of the topological phase of Bi2Se3 under mechanical strain. Phys. Rev. B 84, 085106 (2011).

Liu, W. et al. Anisotropic interactions and strain-induced topological phase transition in Sb2Se3 and Bi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. B 84, 245105 (2011).

Liu, Y., Weinert, M. & Li, L. Spiral growth without dislocations: molecular beam epitaxy of the topological insulator Bi2Se3 on epitaxial graphene/SiC(0001). Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 115501 (2012).

Li, Y-Y. et al. Intrinsic topological insulator Bi2Te3 thin films on Si and their thickness limit. Adv. Mater. 22, 4002–4007 (2010).

Li, H. D. et al. The van der Waals epitaxy of Bi2Se3 on the vicinal Si(111) surface: an approach for preparing high-quality thin films of a topological insulator. New J. Phys. 12, 103038 (2010).

He, L. et al. Epitaxial growth of Bi2Se3 topological insulator thin films on Si (111). J. Appl. Phys. 109, 103702 (2011).

Chang, C-Z. et al. Growth of quantum well films of topological insulator Bi2Se3 on insulating substrate. SPIN 1, 21–25 (2011).

Taskin, A. A., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Achieving surface quantum oscillations in topological insulator thin films of Bi2Se3 . Adv. Mater. 24, 5581–5585 (2012).

Hirth, J. P. & Lothe, J. Theory of dislocations, 2 edn (John Wiley, 1982).

Hytch, M. J., Snoeck, E. & Kilaas, R. Quantitative measurement of displacement and strain fields from HREM micrographs. Ultramicroscopy 74, 131–146 (1998).

Jesson, D. E., Chen, K. M., Pennycook, S. J., Thundat, T. & Warmack, R. J. Crack-like sources of dislocation nucleation and multiplication in thin films. Science 268, 1161–1163 (1995).

Belk, J. G., Pashley, D. W., Joyce, B. A. & Jones, T. S. Dislocation displacement field at the surface of InAs thin films grown on GaAs(110). Phys. Rev. B 58, 16194–16201 (1998).

Zhang, Y. et al. Crossover of the three-dimensional topological insulator Bi2Se3 to the two-dimensional limit. Nature Phys. 6, 584–588 (2010).

Cheng, P. et al. Landau quantization of topological surface states in Bi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 076801 (2010).

Kim, S. et al. Surface scattering via bulk continuum states in the 3D topological insulator Bi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 056803 (2011).

Liu, Y. et al. Charging Dirac states at antiphase domain boundaries in the three-dimensional topological insulator Bi2Se3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 186804 (2013).

Ran, Y., Zhang, Y. & Vishwanath, A. One-dimensional topologically protected modes in topological insulators with lattice dislocations. Nature Phys. 5, 298–303 (2009).

Teo, J. C. Y. & Kane, C. L. Topological defects and gapless modes in insulators and superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 82, 115120 (2010).

Beidenkopf, H. et al. Spatial fluctuations of helical Dirac fermions on the surface of topological insulators. Nature Phys. 7, 939–943 (2011).

Kim, D. et al. Surface conduction of topological Dirac electrons in bulk insulating Bi2Se3 . Nature Phys. 8, 459–463 (2012).

Katsnelson, M. I., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. Chiral tunnelling and the Klein paradox in graphene. Nature Phys. 2, 620–625 (2006).

Tsen, A. W. et al. Tailoring electrical transport across grain boundaries in polycrystalline graphene. Science 336, 1143–1146 (2012).

Kumar, S. B. & Guo, J. Strain-induced conductance modulation in graphene grain boundary. Nano Lett. 12, 1362–1366 (2012).

Dresselhaus, M. S. & Dresselhaus, G. Intercalation compounds of graphite. Adv. Phys. 51, 1–186 (2002).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work is provided by NSF (DMR-1105839).

V.K.L. and P.L.G. thank the Royal Society International Exchanges Scheme for travel support and K. McKenna of the University of York for fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L., Y.Y.L., S.R. and L.Li carried out the MBE growth and STM experiments. D.G., L.Lari., V.K.L. performed the TEM experiment. P.L.G. performed the strain analysis, M.W. performed the DFT calculations. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. L.Li, M.W., and V.K.L. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 1246 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Li, Y., Rajput, S. et al. Tuning Dirac states by strain in the topological insulator Bi2Se3. Nature Phys 10, 294–299 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2898

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2898

This article is cited by

-

Topological minibands and interaction driven quantum anomalous Hall state in topological insulator based moiré heterostructures

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Strain-tuned topological phase transition and unconventional Zeeman effect in ZrTe5 microcrystals

Communications Materials (2022)

-

Topologization of β-antimonene on Bi2Se3 via proximity effects

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

High-throughput Discovery of Topologically Non-trivial Materials using Spin-orbit Spillage

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Unraveling the dislocation core structure at a van der Waals gap in bismuth telluride

Nature Communications (2019)