Abstract

Nanotechnology is an innovative method of freely controlling nanometre-sized materials1. Recent outbreaks of mucosal infectious diseases have increased the demands for development of mucosal vaccines because they induce both systemic and mucosal antigen-specific immune responses2. Here we developed an intranasal vaccine-delivery system with a nanometre-sized hydrogel (‘nanogel’) consisting of a cationic type of cholesteryl-group-bearing pullulan (cCHP). A non-toxic subunit fragment of Clostridium botulinum type-A neurotoxin BoHc/A administered intranasally with cCHP nanogel (cCHP–BoHc/A) continuously adhered to the nasal epithelium and was effectively taken up by mucosal dendritic cells after its release from the cCHP nanogel. Vigorous botulinum-neurotoxin-A-neutralizing serum IgG and secretory IgA antibody responses were induced without co-administration of mucosal adjuvant. Importantly, intranasally administered cCHP–BoHc/A did not accumulate in the olfactory bulbs or brain. Moreover, intranasally immunized tetanus toxoid with cCHP nanogel induced strong tetanus-toxoid-specific systemic and mucosal immune responses. These results indicate that cCHP nanogel can be used as a universal protein-based antigen-delivery vehicle for adjuvant-free intranasal vaccination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Beginning in 2003, an enormous research initiative—Grand Challenges in Global Health—has been organized worldwide with the support of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the US National Institutes of Health. Its aim is to overcome the global infectious disease problems affecting human health today3. The development of a new-generation needle-free mucosal vaccine has been proposed as one of the initiative’s most important goals, because it can elicit antigen-specific systemic humoral and cellular immune responses and simultaneously induce mucosal immunity, especially in the aero-digestive and reproductive tracts2,3,4. FluMist, which is composed of cold-adapted trivalent live influenza viruses, is a well-known example as the first advanced intranasal vaccine to be used in US public health, in 2003 (ref. 5). Since then, tremendous efforts have been made to further develop intranasal vaccine technology. Subunit intranasal vaccination is expected to be the safest strategy, because it should have a low risk of causing unfavourable and undesired biological reactions6. However, intranasal administration of a subunit antigen alone is generally insufficient for induction of antigen-specific immune responses. As a result, an adjuvant such as a bacterial toxin generally needs to be added, but these toxins are poorly tolerated by humans7.

Cholera toxin and heat-labile enterotoxin have been extensively used as potent mucosal adjuvants in experimental animal studies because of their multiple immune-potentiating functions: they activate immunocompetent cells, including dendritic cells and B cells, and thus induce antigen-specific mucosal immunity7,8,9. However, a human clinical trial carried out in Switzerland from 2000 to 2001 to develop an intranasal influenza vaccine with inactivated influenza virus combined with a small amount of heat-labile enterotoxin was withdrawn because the co-administered heat-labile enterotoxin was suspected of causing Bell’s palsy, a rare condition, in vaccinated subjects10. In addition, a separate study in mice demonstrated that the toxin-based adjuvant migrated into, and accumulated in, the olfactory tissues11. As a result of these safety issues, the development of intranasal vaccines employing the co-administration of toxin-based adjuvants has rapidly declined. Further scientific and technological innovations that will help the development of safe but effective adjuvant-free intranasal vaccines are, therefore, of high priority in global health.

Application of biomaterials, such as polymer nanoparticles and liposomes, has a great potential in vaccine development and immunotherapy12,13,14. In particular, nanometre-sized (<100 nm) polymer hydrogels (nanogels) have attracted growing interest as nanocarriers, especially in drug-delivery systems15,16. We have developed a new method of creating a series of functional nanogels through self-assembly of associating polymers17. One of these polymers, the cholesteryl-group-bearing pullulan (CHP) forms physically crosslinked nanogels by self-assembly in water18,19,20,21,22 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1). The CHP nanogels trap various proteins by mainly hydrophobic interactions23 and acquire chaperon-like activity because the proteins are trapped inside a hydrated nanogel polymer network (nanomatrix) without aggregating and are gradually released in the native form20,24. These properties make the CHP nanogel a superior nanocarrier for protein delivery, especially in the area of cancer vaccine development25,26. In fact, recent successful clinical studies have clearly shown that subcutaneous injection of CHP nanogel carrying the cancer antigen HER2 (CHP–HER2) or NY-ESO-1 (CHP–NY-ESO-1) effectively induces antigen-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses and antibody production21,22. Therefore, the technological successes have been extended to the use of a CHP nanogel strategy to develop adjuvant-free intranasal vaccines that can induce antigen-specific protective immunity against infectious diseases.

a, cCHP nanogel was generated from a cationic type of cholesteryl-group-bearing pullulan. b, Superimposition of sagittal and transverse (photo insets) PET images on the corresponding computed tomography images showed that intranasally administered cCHP nanogels carrying [18F]-labelled BoHc/A were effectively delivered to the nasal mucosa. c, Direct quantitative study with [111In]-labelled BoHc/A further demonstrated that BoHc/A was retained in the nasal tissues for more than two days after intranasal immunization with cCHP nanogel. In contrast, most naked BoHc/A disappeared from the nasal cavity within 6 h after administration.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of CHP nanogel as a new vehicle for adjuvant-free intranasal vaccines, we prepared and used an Escherichia-coli-derived recombinant non-toxic receptor-binding fragment (heavy-chain C terminus) of C. botulinum type-A neurotoxin subunit antigen Hc (BoHc/A) as a prototype vaccine antigen because the immunogenicity of BoHc/A has already been demonstrated elsewhere27,28. In the initial study for evaluation of BoHc/A quality, because the antigen was highly purified, only a negligible amount of endotoxin with no in vivo biological effects on immunocompetent cells was detected (Supplementary Table S1; ref. 29). C. botulinum has been defined as a category A bioterrorism agent by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention because of the strong neural toxicity of C. botulinum-producing neurotoxin (BoNT), which could enable the bacterium to be disseminated as a biological weapon. Thus, the development of an effective vaccine—especially a mucosal vaccine—against BoNT is important for global deterrence of bioterrorism30.

We intranasally immunized mice with CHP nanogel carrying BoHc/A (CHP–BoHc/A). It should be noted that the levels of endotoxin carried by the CHP nanogel were undetectable (Supplementary Table S1). Subsequent quality analyses of CHP–BoHc/A to confirm the nanometre-scale size uniformity and complex formation by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and fluorescence response energy transfer (FRET) analyses showed that the CHP nanogel continuously formed the nanoparticles after the incorporation of BoHc/A (Supplementary Fig. S2). However, intranasally administered CHP–BoHc/A was no better than naked BoHc/A for inducing BoNT/A-specific antibody responses (Supplementary Fig. S3a,b). These results suggest that CHP–BoHc/A is delivered minimally to the upper respiratory immune system because the mucosal tissues are tightly covered by an epithelial layer. In support of this hypothesis, the use of CHP nanogel did not enhance the BoHc/A uptake by nasal dendritic cells when compared to intranasal administration of naked BoHc/A (Supplementary Fig. S3c). Therefore, we next developed an endotoxin-free cationic type of CHP (cCHP) nanogel containing 15 amino groups per 100 glucose units (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1 and Table S1) to improve the antigen-delivery efficacy of CHP nanogel to the anionic epithelial cell layer. DLS and FRET analyses showed that the cCHP nanogel possessed similar structural characteristics to the CHP nanogel because it maintained nanoscale size uniformity even after the incorporation of BoHc/A (Supplementary Fig. S2). In addition, consistent with its positive zeta-potential (Supplementary Table S2), it strongly interacted with the membranes of HeLa cells (Supplementary Fig. S4a) and was subsequently taken up into the cells by endocytosis (Supplementary Fig. S4b). These results are consistent with our previous finding that cCHP nanogel effectively delivered several proteins into cells in vitro31. Furthermore, an in vivo imaging study using small-animal positron emission tomography (PET) and X-ray computed tomography showed clearly that intranasally administered cCHP nanogel carrying [18F]-labelled BoHc/A was effectively delivered to, and continuously retained by, the nasal mucosa. In contrast, most of the [18F]-labelled BoHc/A administered intranasally without cCHP nanogel disappeared from the nasal cavity within 6 h (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S5). A direct counting assay using a different radioisotope [111In] with a long half-life (2.805 days) further demonstrated that BoHc/A was retained in the nasal cavity for more than two days when administered intranasally with cCHP nanogel (Fig. 1c).

To explore the efficacy of cCHP nanogel as a new adjuvant-free delivery vehicle for intranasal vaccination, we next tested whether intranasal immunization with cCHP–BoHc/A would effectively induce BoNT/A-specific mucosal IgA antibody responses. A histochemical study showed that the numbers of IgA-committed B cells markedly increased in the lamina propria and paranasal sinuses of the nasal passages on intranasal immunization with cCHP–BoHc/A, but not with naked BoHc/A or control PBS (Fig. 2a). A subsequent enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot study analysing mononuclear cells isolated from the nasal cavities of cCHP–BoHc/A-immunized mice directly confirmed induction of BoNT/A-specific IgA-producing cells (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, high titres of BoNT/A-specific IgA antibodies were detected in only those nasal washes collected from mice immunized with cCHP–BoHc/A, not with naked BoHc/A or control PBS (Fig. 2c).

a,b, BoNT/A-specific IgA-producing cells (or antibody-forming cells: AFCs) were effectively induced and recruited in the lamina propria and paranasal sinuses of the nasal mucosa 1 week after final immunization with cCHP–BoHc/A. c, Vigorous BoNT/A-specific IgA antibody responses were observed in nasal washes collected from mice intranasally immunized with cCHP–BoHc/A, but not from those given naked BoHc/A or control PBS. d, Strong BoNT/A-specific serum IgG antibody responses were induced by intranasal immunization with cCHP–BoHc/A. e,f, Mice intranasally vaccinated with cCHP–BoHc/A were completely protected from both intraperitoneal challenge with BoNT/A and intranasal exposure to the progenitor toxin.

As mucosal vaccination induces two-layered immunity (that is, in both the systemic and the mucosal compartments)2,4, our next experiments were designed to determine whether BoNT/A-specific serum antibody responses were induced by intranasal immunization with cCHP–BoHc/A. Vigorous BoNT/A-specific serum IgG antibody responses were induced in cCHP–BoHc/A-vaccinated mice but not in mice immunized with naked BoHc/A or control PBS (Fig. 2d). To confirm the broad utility of this strategy with cCHP nanogel, we next evaluated the efficacy of intranasal administration of cCHP nanogel carrying a second prototype vaccine antigen, tetanus toxoid (cCHP–TT). As we expected, high titres of tetanus-toxoid-specific serum IgG as well as mucosal IgA antibodies were induced by intranasal administration of cCHP–TT (Supplementary Fig. S6). These findings indicate that the cCHP nanogel can be used universally as a new protein antigen delivery vehicle for intranasal vaccines.

We next carried out toxin-challenge experiments to confirm the ability of intranasal immunization with cCHP–BoHc/A to neutralize BoNT/A and its progenitor in vivo. BoNT produced by C. botulinum usually forms a large complex called progenitor toxin with non-toxic accessory components, such as haemagglutinin, which are involved in binding to the mucosal epithelium32. It has been suggested that, on infection, the progenitor toxin binds to the mucosal epithelium; BoNT/A is then released into the blood circulation after detaching from these accessory components and finally interacts with nerve cells, causing botulism33. After intraperitoneal (i.p.) challenge with BoNT/A (500 ng,5.5×104 i.p. LD50, where LD50 represents the dose lethal to 50% of animals tested), mice intranasally immunized with cCHP–BoHc/A survived without any clinical signs, whereas those that had received naked BoHc/A or control PBS almost immediately developed neurological signs and died within half a day (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, mice intranasally immunized with cCHP–BoHc/A were completely protected from the effects of intranasal exposure to the progenitor toxin (10 μg, 2×105 i.p. LD50) (Fig. 2f). Thus, the intranasal vaccine formulation of cCHP–BoHc/A effectively induces both systemic and mucosal protective immunity against lethal exposure to both BoNT/A and its progenitor without the co-administration of mucosal adjuvant.

To directly address how cCHP nanogel initiates and accelerates the immune responses against incorporated vaccine antigen without the use of a mucosal adjuvant, we next carried out a series of histochemical studies with tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated cCHP nanogel carrying Alexa-Fluor-647-conjugated BoHc/A. As we expected, within 1 h of intranasal administration, antigen-coupled fluorescence signals were observed in antigen-sampling M cells recognized by our previously established monoclonal antibody NKM 16-2-4 (ref. 34), in the nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissues, which are inductive tissues for the airway mucosal immune system4 (Supplementary Fig. S7a). However, because the nasal epithelium is anatomically widespread, cCHP–BoHc/A was universally distributed in the apical membrane of the nasal epithelium, and its density was much greater than that detected in the follicle-associated epithelium of nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissues (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. S7b). Examination of high-magnification images revealed that the cCHP–BoHc/A was internalized into the nasal epithelium immediately after the intranasal administration; BoHc/A was then detached gradually from the cCHP nanogel in a controlled manner in the nasal epithelial cells (Fig. 3b). In this regard, we previously showed that the proteins encapsulated by nanogels were released by protein exchange in the presence of excess amounts of other proteins, such as cellular components or enzymes31. In fact, the in vitro circular dichroism analysis showed that the secondary structure of BoHc/A was changed after the molecule was incorporated into the CHP nanogel but recovered after it was released (Fig. 3c). These results suggest that the cCHP nanogel acts as an artificial chaperone for intranasal vaccine antigen, leading to the induction of antigen-specific respiratory immune responses. In support of our hypothesis, the flow cytometric and immunohistochemical analyses showed that, within 6 h after administration of the BoHc/A with cCHP nanogel, the BoHc/A released from the nasal epithelium by exocytosis was effectively taken up by CD11c+ dendritic cells located in both the epithelial layer and the lamina propria of the nasal cavity (Fig. 4a,b). It should be emphasized that the immunological role of cCHP nanogel is just to convey the vaccine antigen into the respiratory immune system effectively; it does not provide adjuvant-like activity to dendritic cells, because the bone-marrow-derived naive dendritic cells cultivated with cCHP nanogel did not enhance the expression of the co-stimulatory and antigen-presentation molecules (Supplementary Fig. S8). Moreover, nasal dendritic cells spontaneously expressed these molecules, probably because of chronic stimulation by inhaled environmental antigens, and their expression levels were not changed by intranasal administration with cCHP–BoHc/A (Supplementary Fig. S9). Therefore, the optimum antigen delivery offered by cCHP nanogel to activated nasal dendritic cells over a wide area of the nasal mucosa would be an effective strategy for inducing antigen-specific protective immune responses.

a, Intranasally administered cCHP–BoHc/A but not naked BoHc/A was effectively attached to the apical membrane of nasal epithelium. b, BoHc/A was subsequently released from the cCHP nanogel and transported into the epithelial layer. c, Circular dichroism analysis showed that the ellipticity (θ) value of BoHc/A, which was decreased to −15.2 mdeg after the BoHc/A was incorporated into cCHP nanogel, recovered to −9.4 mdeg after the release of BoHc/A from the cCHP nanogel by treatment with methyl-ϐ-cyclodextrin. (1) Native BoHc/A, (2) BoHc/A heated for 5 h at 45 °C, (3) BoHc/A incubated with cCHP nanogel for 5 h at 45 °C, (4) cCHP–BoHc/A treated with methyl-ϐ-cyclodextrin for 1 h at 25 °C.

a,b, Flow cytometric (a) and immunohistochemical analyses (b) showed that BoHc/A released from cCHP nanogel was effectively taken up by CD11c+ dendritic cells located in the epithelial layer and lamina propria of the nasal cavity, as shown by arrowheads. CD11c+ dendritic cells and the basal layer of nasal epithelium in b are shown by arrows and dotted lines, respectively. c, The radioisotope counting assay showed that intranasally administered cCHP nanogel carrying [111In]-labelled BoHc/A did not accumulate in the olfactory bulbs or brain. In contrast, [111In]-labelled cholera toxin B subunit (CT-B), used as a positive control, accumulated in the olfactory bulbs from 6 h after administration.

As the most important issue in intranasal vaccine development is to overcome safety concerns about the potential dissemination of intranasal vaccine antigens to the central nervous system (CNS), we carried out an in vivo tracer study with [111In]-labelled BoHc/A. When cCHP nanogel carrying [111In]-labelled BoHc/A was administered intranasally, no transition into the olfactory bulbs or brain was observed over a two-day period after administration (Fig. 4c). In contrast, when [111In]-labelled cholera toxin B subunit, which can reach and accumulate in olfactory tissues11, was administered intranasally with the same dose of radioisotope as used with the cCHP–BoHc/A, the radioisotope count in the olfactory bulbs was significantly higher than with cCHP nanogel holding [111In]-labelled BoHc/A (Fig. 4c). These results support the hypothesis that cCHP nanogel administered intranasally possesses no risk of redirecting the vaccine antigen into the CNS when administered intranasally and, therefore, can be used as a safe delivery vehicle for intranasal vaccines.

In essence, the nanogel antigen delivery system now opens up a new avenue for the creation of adjuvant-free intranasal vaccines. Taken in terms of its validity in leading to the induction of effective immune responses at both systemic and mucosal compartments without a concern for the deposition of vaccine antigen into the CNS, it would provide a unique and attractive vaccine strategy for the control of respiratory infectious diseases (for example, influenza).

Methods

Animals.

Female BALB/c mice between 6 and 8 weeks old were maintained in the experimental animal facilities at the Institute of Medical Science of The University of Tokyo and at Hamamatsu Photonics K.K. All experiments were carried out according to the guidelines provided by the Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Tokyo and Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.

Preparation of nanogel vaccine.

CHP or cCHP nanogel synthesized as described previously31,35 was mixed for 5 h at 45 °C at a 1:1 molecular ratio with vaccine antigen (BoHc/A expressed by E. coli or tetanus toxoid; kindly provided by the Research Foundation for Microbial Diseases of Osaka University). The FRET was determined by an FP-6500 fluorescence spectrometer (Jasco) with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated BoHc/A and TRITC-conjugated CHP or cCHP nanogel. The DLS of CHP or cCHP carrying, or not carrying BoHc/A, and the zeta-potential of BoHc/A with or without cCHP nanogel were determined with a Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Malvern Instruments). The circular dichroism spectra of BoHc/A before and after being incorporated into the cCHP nanogel, and after release from the cCHP nanogel by treatment with 15 mM of methyl-ϐ-cyclodextrin, were obtained by using a J-720 spectropolarimeter (Jasco). To determine the cellular uptake in vitro, HeLa cells were treated with 10 nM of CHP or cCHP nanogel carrying FITC-conjugated BoHc/A, or of FITC-conjugated naked BoHc/A, for 4 h and analysed by flow cytometry with FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson).

In vivo imaging study and radioisotope counting assay.

cCHP nanogel incorporating [18F]-labelled BoHc/A was administered intranasally to mice and the distribution of radioisotope in the nasal cavity was determined by using a small-animal PET system (Clairvivo PET, Shimadzu Corporation)36. The radioisotope signals were measured for 10 h after administration and were superimposed on the image obtained by a small-animal X-ray computed tomography scanner (Clairvivo CT, Shimadzu Corporation). The images were analysed by using a PMOD software package (PMOD Technologies) and expressed as standardized uptake values (SUV) calculated from radioactivity in the volumes of interest. To trace the antigen for longer, [111In]-labelled naked BoHc/A was administered intranasally with or without cCHP nanogel and the radioisotope counts in the nasal mucosa, olfactory bulbs and brain were directly measured by a γ-counter (1480 WIZARD, PerkinElmer) 10 min, 1, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h after administration. As a control, [111In]-labelled cholera toxin B subunit37 was administered intranasally. SUV was calculated as radioactivity (c.p.m.) per gram of tissue divided by the ratio of injection dose (1×106 c.p.m.) to body weight.

Immunization study.

CHP or cCHP nanogel (each 88.9 μg for BoHc/A or 78.5 μg for tetanus toxoid) carrying BoHc/A (10 μg) or tetanus toxoid (30 μg), or the same amount of naked BoHc/A or tetanus toxoid dissolved in 15 μl of PBS, was administered intranasally to mice on three occasions at 1-week intervals. Sera were collected before, and 1 week after, each immunization, and nasal wash samples were taken 1 week after final immunization for antigen-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as described previously34,38. Mononuclear cells were isolated from the nasal passages 1 week after the final immunization and subjected to antigen-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot analysis as shown in a previous study38.

Neutralizing assay.

To analyse the toxin-neutralizing activity of cCHP–BoHc/A-induced serum IgG and nasal IgA antibodies, the immunized mice were intraperitoneally challenged with 500 ng of BoNT/A (5.5×104 i.p. LD50) diluted in 100 μl of 0.2% gelatin/PBS or intranasally exposed to 10 μg (in 10 μl PBS, 5 μl per nostril) of C. botulinumtype-A progenitor toxin (2×105 i.p. LD50, Wako). Clinical signs and survival rates were observed for 7 days, as described previously34,38.

Histochemistry and flow cytometric analyses.

Frozen sections of nasal tissues prepared from immunized mice were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgA (BD Biosciences). To determine the distribution of cCHP–BoHc/A after intranasal administration, either TRITC-conjugated cCHP nanogel carrying Alexa-Fluor-647-conjugated BoHc/A, or Alexa-Fluor-647-conjugated naked BoHc/A, was administered intranasally and the sections of nasal tissues were stained with FITC-conjugated NKM 16-2-4 (ref. 34) or biotinylated anti-CD11c (BD Biosciences). For CD11c staining, the sections were then treated with streptavidin/horseradish peroxidase diluted 1:1000 (Pierce) followed by tyramide–FITC (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences). All sections were finally counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Sigma) and analysed under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (TCS SP2, Leica) or a fluorescence microscope (BZ-9000, Keyence). To determine the antigen uptake by dendritic cells, cCHP nanogel carrying Alexa-Fluor-647-conjugated BoHc/A, Alexa-Fluor-647-conjugated naked BoHc/A or control PBS was administered intranasally. After 6 h, mononuclear cells were isolated from the nasal passages and stained with FITC-conjugated CD11c (BD Biosciences). The frequency of BoHc/A+ CD11c+ cells was analysed by flow cytometry.

Data analysis.

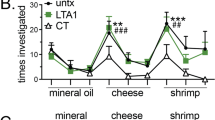

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. All analyses for statistically significant differences were carried out by Tukey’s t-test, with significance indicated by p values of <0.001 (***), <0.01 (**) and <0.05 (*).

Change history

02 July 2010

On the first page of the PDF and printed versions of this Letter originally published, the full list of authors and their affiliations should have been included. This has been corrected in the PDF version of this Letter.

References

Wagner, V., Dullaart, A., Bock, A. K. & Zweck, A. The emerging nanomedicine landscape. Nature Biotechnol. 24, 1211–1217 (2006).

Holmgren, J. & Czerkinsky, C. Mucosal immunity and vaccines. Nature Med. 11, S45–S53 (2005).

Varmus, H. et al. Public health. Grand challenges in global health. Science 302, 398–399 (2003).

Kiyono, H. & Fukuyama, S. NALT- versus Peyer’s-patch-mediated mucosal immunity. Nature Rev. Immunol. 4, 699–710 (2004).

Belshe, R., Lee, M. S., Walker, R. E., Stoddard, J. & Mendelman, P. M. Safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of intranasal, live attenuated influenza vaccine. Exp. Rev. Vaccines 3, 643–654 (2004).

Lavelle, E. C. Generation of improved mucosal vaccines by induction of innate immunity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62, 2750–2770 (2005).

Yuki, Y. & Kiyono, H. New generation of mucosal adjuvants for the induction of protective immunity. Rev. Med. Virol. 13, 293–310 (2003).

Xu-Amano, J. et al. Helper T cell subsets for immunoglobulin A responses: Oral immunization with tetanus toxoid and cholera toxin as adjuvant selectively induces Th2 cells in mucosa associated tissues. J. Exp. Med. 178, 1309–1320 (1993).

Takahashi, I. et al. Mechanisms for mucosal immunogenicity and adjuvancy of Escherichia coli labile enterotoxin. J. Infect. Dis. 173, 627–635 (1996).

Mutsch, M. et al. Use of the inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine and the risk of Bell’s palsy in Switzerland. New Engl. J. Med. 350, 896–903 (2004).

van Ginkel, F. W., Jackson, R. J., Yuki, Y. & McGhee, J. R. Cutting edge: The mucosal adjuvant cholera toxin redirects vaccine proteins into olfactory tissues. J. Immunol. 165, 4778–4782 (2000).

Reddy, S. T., Swartz, M. A. & Hubbell, J. A. Targeting dendritic cells with biomaterials: Developing the next generation of vaccines. Trends Immunol. 27, 573–579 (2006).

Peek, L. J., Middaugh, C. R. & Berkland, C. Nanotechnology in vaccine delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 60, 915–928 (2008).

Sharma, S., Mukkur, T. K., Benson, H. A. & Chen, Y. Pharmaceutical aspects of intranasal delivery of vaccines using particulate systems. J. Pharm. Sci. 98, 812–843 (2009).

Oh, J. K., Drumright, R., Siegwart, D. J. & Matyjaszewski, K. The development of microgels/nanogels for drug delivery applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 33, 448–477 (2008).

Reamdonck, K., Demeester, J. & Smedt, S. D. Advanced nanogel engineering for drug delivery. Soft Matter 5, 707–715 (2009).

Morimoto, N., Nomura, S., Miyazawa, N. & Akiyoshi, K. Nanogel engineered design for polymeric drug delivery. Polym. Drug Deliv. II, 88–101 (2006).

Akiyoshi, K., Deguchi, S., Moriguchi, N., Yamaguchi, S. & Sunamoto, J. Self-aggregates of hydrophobized polysaccharides in water. Macromolecules 26, 3062–3068 (1993).

Akiyoshi, K., Deguchi, S., Tajima, T., Nishikawa, T. & Sunamoto, J. Microscopic structure and thermoresponsiveness of a hydrogel nanoparticle by self-assembly of a hydrophobized polysaccharide. Macromolecules 30, 857–861 (1997).

Nomura, Y., Ikeda, M., Yamaguchi, N., Aoyama, Y. & Akiyoshi, K. Protein refolding assisted by self-assembled nanogels as novel artificial molecular chaperone. FEBS Lett. 553, 271–276 (2003).

Uenaka, A. et al. T cell immunomonitoring and tumor responses in patients immunized with a complex of cholesterol-bearing hydrophobized pullulan (CHP) and NY-ESO-1 protein. Cancer Immun. 7, 9 (2007).

Kageyama, S. et al. Humoral immune responses in patients vaccinated with 1-146 HER2 protein complexed with cholesteryl pullulan nanogel. Cancer Sci. 99, 601–607 (2008).

Nishikawa, T., Akiyoshi, K. & Sunamoto, J. Macromolecular complexation between bovine serum albumin and the self-assembled hydrogel nanoparticle of hydrophobized polysaccharides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 6110–6115 (1996).

Akiyoshi, K., Sasaki, Y. & Sunamoto, J. Molecular chaperone-like activity of hydrogel nanoparticles of hydrophobized pullulan: Thermal stabilization with refolding of carbonic anhydrase B. Bioconjug. Chem. 10, 321–324 (1999).

Gu, X. G. et al. A novel hydrophobized polysaccharide/oncoprotein complex vaccine induces in vitro and in vivo cellular and humoral immune responses against HER2-expressing murine sarcomas. Cancer Res. 58, 3385–3390 (1998).

Ikuta, Y. et al. Presentation of a major histocompatibility complex class 1-binding peptide by monocyte-derived dendritic cells incorporating hydrophobized polysaccharide-truncated HER2 protein complex: Implications for a polyvalent immuno-cell therapy. Blood 99, 3717–3724 (2002).

Byrne, M. P., Smith, T. J., Montgomery, V. A. & Smith, L. A. Purification, potency, and efficacy of the botulinum neurotoxin type A binding domain from Pichia pastoris as a recombinant vaccine candidate. Infect. Immun. 66, 4817–4822 (1998).

Ravichandran, E. et al. Trivalent vaccine against botulinum toxin serotypes A, B, and E that can be administered by the mucosal route. Infect. Immun. 75, 3043–3054 (2007).

Ultrich, J., Cantrell, J., Gustafson, G., Rudbach, J. & Hiernant, J. The Adjuvant Activity of Monophosphoryl Lipid A 133–143 (CRC Press, 1991).

Fujihashi, K., Staats, H. F., Kozaki, S. & Pascual, D. W. Mucosal vaccine development for botulinum intoxication. Exp. Rev. Vaccines 6, 35–45 (2007).

Ayame, H., Morimoto, N. & Akiyoshi, K. Self-assembled cationic nanogels for intracellular protein delivery. Bioconjug. Chem. 19, 882–890 (2008).

Inoue, K. et al. Molecular composition of Clostridium botulinum type A progenitor toxins. Infect. Immun. 64, 1589–1594 (1996).

Fujinaga, Y., Matsumura, T., Jin, Y., Takegahara, Y. & Sugawara, Y. A novel function of botulinum toxin-associated proteins: HA proteins disrupt intestinal epithelial barrier to increase toxin absorption. Toxicon 54, 583–586 (2009).

Nochi, T. et al. A novel M cell-specific carbohydrate-targeted mucosal vaccine effectively induces antigen-specific immune responses. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2789–2796 (2007).

Akiyoshi, K. et al. Self-assembled hydrogel nanoparticle of cholesterol-bearing pullulan as a carrier of protein drugs: Complexation and stabilization of insulin. J. Control. Release 54, 313–320 (1998).

Mizuta, T. et al. Performance evaluation of a high-sensitivity large-aperture small-animal PET scanner: ClairvivoPET. Ann. Nucl. Med. 22, 447–455 (2008).

Yuki, Y. et al. Production of a recombinant hybrid molecule of cholera toxin-B-subunit and proteolipid–protein–peptide for the treatment of experimental encephalomyelitis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 74, 62–69 (2001).

Kobayashi, R. et al. A novel neurotoxoid vaccine prevents mucosal botulism. J. Immunol. 174, 2190–2195 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Victor Garcia of The University of North Carolina for editing the manuscript and K. Kubota of the Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, for his technical support of the radioisotope study. We also thank A. Watanabe and K. Matsuzaki of Mercian Corporation for culturing the E. coli for preparation of BoHc/A. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and the Ministry of Health and Labour of Japan (H.K., K.A., Y.Y.); the Global Center of Excellence Program ‘Center of Education and Research for Advanced Genome-Based Medicine—For Personalized Medicine and the Control of Worldwide Infectious Diseases’ (H.K.); a Research Fellowship of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (T.N.); the Research and Development Program for New Bio-industry Initiatives of the Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution (Y.Y.); and the Global Center of Excellence Program, ‘International Research Center for Molecular Science in Tooth and Bone Diseases’ (K.A., Ha.T.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.N. and Y.Y. designed and carried out the experiments, analysed the results and wrote the manuscript. Hi.T., S. Kozaki, K.A. and H.K. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Ha.T., S-i.S., M.M., T.K., N.H., N.K., I.G.K., A.S., D.T., S. Kurokawa and Y.T. carried out the experiments.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

(PDF 2306 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nochi, T., Yuki, Y., Takahashi, H. et al. Nanogel antigenic protein-delivery system for adjuvant-free intranasal vaccines. Nature Mater 9, 572–578 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2784

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2784

This article is cited by

-

The Age of Multistimuli-responsive Nanogels: The Finest Evolved Nano Delivery System in Biomedical Sciences

Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering (2020)

-

Structural and Functional Analysis of Pullulanase Type 1 (PulA) from Geobacillus thermopakistaniensis

Molecular Biotechnology (2020)

-

Staphylococcus aureus-specific IgA antibody in milk suppresses the multiplication of S. aureus in infected bovine udder

BMC Veterinary Research (2019)

-

Cascade enzymes within self-assembled hybrid nanogel mimicked neutrophil lysosomes for singlet oxygen elevated cancer therapy

Nature Communications (2019)