Abstract

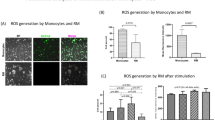

Sepsis causes over 200,000 deaths yearly in the US; better treatments are urgently needed. Administering bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs—also known as mesenchymal stem cells) to mice before or shortly after inducing sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture reduced mortality and improved organ function. The beneficial effect of BMSCs was eliminated by macrophage depletion or pretreatment with antibodies specific for interleukin-10 (IL-10) or IL-10 receptor. Monocytes and/or macrophages from septic lungs made more IL-10 when prepared from mice treated with BMSCs versus untreated mice. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated macrophages produced more IL-10 when cultured with BMSCs, but this effect was eliminated if the BMSCs lacked the genes encoding Toll-like receptor 4, myeloid differentiation primary response gene-88, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-1a or cyclooxygenase-2. Our results suggest that BMSCs (activated by LPS or TNF-α) reprogram macrophages by releasing prostaglandin E2 that acts on the macrophages through the prostaglandin EP2 and EP4 receptors. Because BMSCs have been successfully given to humans and can easily be cultured and might be used without human leukocyte antigen matching, we suggest that cultured, banked human BMSCs may be effective in treating sepsis in high-risk patient groups.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

06 April 2009

In the version of this article initially published, the labeling in (Figure 4) was incorrect. In panel (b), the cells in the left two FACS plots are shown based on their size (FSC, y axis) and CD11b expression (x axis), and the cells in the right two FACS plots are shown based on their F4/80 expression (y axis) and GR1 expression (x axis). In panel (c), the curves should start at 1 h. In panel (d), the text labeling the y axis should read “in vitro,” not “in vivo.” The errors have been corrected in the HTML and PDF versions of this article.

References

Ulloa, L. & Tracey, K.J. The “cytokine profile”: a code for sepsis. Trends Mol. Med. 11, 56–63 (2005).

Le Blanc, K. et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet 363, 1439–1441 (2004).

Noel, D., Djouad, F., Bouffi, C., Mrugala, D. & Jorgensen, C. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and immune tolerance. Leuk. Lymphoma 48, 1283–1289 (2007).

Rasmusson, I. Immune modulation by mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Cell Res. 312, 2169–2179 (2006).

Ringden, O. et al. Tissue repair using allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells for hemorrhagic cystitis, pneumomediastinum and perforated colon. Leukemia 21, 2271–2276 (2007).

Bochud, P.Y. & Calandra, T. Pathogenesis of sepsis: new concepts and implications for future treatment. BMJ 326, 262–266 (2003).

Calandra, T. Pathogenesis of septic shock: implications for prevention and treatment. J. Chemother. 13 (Spec. No. 1), 173–180 (2001).

Hubbard, W.J. et al. Cecal ligation and puncture. Shock 24 Suppl 1, 52–57 (2005).

Togel, F. et al. Vasculotropic, paracrine actions of infused mesenchymal stem cells are important to the recovery from acute kidney injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 292, F1626–F1635 (2007).

Togel, F. et al. Administered mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischemic acute renal failure through differentiation-independent mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 289, F31–F42 (2005).

Semedo, P. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate tissue damages triggered by renal ischemia and reperfusion injury. Transplant. Proc. 39, 421–423 (2007).

Lange, C. et al. Administered mesenchymal stem cells enhance recovery from ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute renal failure in rats. Kidney Int. 68, 1613–1617 (2005).

Shinkai, Y. et al. RAG-2–deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell 68, 855–867 (1992).

Habu, S. et al. In vivo effects of anti-asialo GM1. I. Reduction of NK activity and enhancement of transplanted tumor growth in nude mice. J. Immunol. 127, 34–38 (1981).

Kasai, M. et al. In vivo effect of anti-asialo GM1 antibody on natural killer activity. Nature 291, 334–335 (1981).

van Rooijen, N., Sanders, A. & van den Berg, T.K. Apoptosis of macrophages induced by liposome-mediated intracellular delivery of clodronate and propamidine. J. Immunol. Methods 193, 93–99 (1996).

Moore, K.W., O'Garra, A., de Waal Malefyt, R., Vieira, P. & Mosmann, T.R. Interleukin-10. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11, 165–190 (1993).

Wang, J., Wakeham, J., Harkness, R. & Xing, Z. Macrophages are a significant source of type 1 cytokines during mycobacterial infection. J. Clin. Invest. 103, 1023–1029 (1999).

Bonder, C.S. et al. P-selectin can support both TH1 and TH2 lymphocyte rolling in the intestinal microvasculature. Am. J. Pathol. 167, 1647–1660 (2005).

Perretti, M., Szabo, C. & Thiemermann, C. Effect of interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 on leucocyte migration and nitric oxide production in the mouse. Br. J. Pharmacol. 116, 2251–2257 (1995).

Cassatella, M.A. The neutrophil: one of the cellular targets of interleukin-10. Int. J. Clin. Lab. Res. 28, 148–161 (1998).

Ajuebor, M.N. et al. Role of resident peritoneal macrophages and mast cells in chemokine production and neutrophil migration in acute inflammation: evidence for an inhibitory loop involving endogenous IL-10. J. Immunol. 162, 1685–1691 (1999).

Hernandez, L.A. et al. Role of neutrophils in ischemia-reperfusion–induced microvascular injury. Am. J. Physiol. 253, H699–H703 (1987).

Jaeschke, H. & Smith, C.W. Mechanisms of neutrophil-induced parenchymal cell injury. J. Leukoc. Biol. 61, 647–653 (1997).

Nussler, A.K., Wittel, U.A., Nussler, N.C. & Beger, H.G. Leukocytes, the Janus cells in inflammatory disease. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 384, 222–232 (1999).

Matthijsen, R.A. et al. Myeloperoxidase is critically involved in the induction of organ damage after renal ischemia reperfusion. Am. J. Pathol. 171, 1743–1752 (2007).

Jung, Y.J., Isaacs, J.S., Lee, S., Trepel, J. & Neckers, L. IL-1beta-mediated up-regulation of HIF-1α via an NFkappaB/COX-2 pathway identifies HIF-1 as a critical link between inflammation and oncogenesis. FASEB J. 17, 2115–2117 (2003).

Nakao, S. et al. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)-induced prostaglandin E2 release is mediated by the activation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) transcription via NFκB in human gingival fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 238, 11–18 (2002).

Ramsay, R.G., Ciznadija, D., Vanevski, M. & Mantamadiotis, T. Transcriptional regulation of cyclo-oxygenase expression: three pillars of control. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 16, 59–67 (2003).

Aggarwal, S. & Pittenger, M.F. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood 105, 1815–1822 (2005).

Sotiropoulou, P.A., Perez, S.A., Gritzapis, A.D., Baxevanis, C.N. & Papamichail, M. Interactions between human mesenchymal stem cells and natural killer cells. Stem Cells 24, 74–85 (2006).

Pevsner-Fischer, M. et al. Toll-like receptors and their ligands control mesenchymal stem cell functions. Blood 109, 1422–1432 (2007).

Crisostomo, P.R. et al. Gender differences in injury induced mesenchymal stem cell apoptosis and VEGF, TNF, IL-6 expression: role of the 55 kDa TNF receptor (TNFR1). J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 42, 142–149 (2007).

Park, Y.K. et al. Nitric oxide donor, (+/−)-S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine, stabilizes transactive hypoxia-inducible factor-1α by inhibiting von Hippel-Lindau recruitment and asparagine hydroxylation. Mol. Pharmacol. 74, 236–245 (2008).

Bal-Price, A., Gartlon, J. & Brown, G.C. Nitric oxide stimulates PC12 cell proliferation via cGMP and inhibits at higher concentrations mainly via energy depletion. Nitric Oxide 14, 238–246 (2006).

Bianco, P., Riminucci, M., Gronthos, S. & Robey, P.G. Bone marrow stromal stem cells: nature, biology, and potential applications. Stem Cells 19, 180–192 (2001).

Chamberlain, G., Fox, J., Ashton, B. & Middleton, J. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells 25, 2739–2749 (2007).

Mansilla, E. et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells are tolerized by mice and improve skin and spinal cord injuries. Transplant. Proc. 37, 292–294 (2005).

van Laar, J.M. & Tyndall, A. Adult stem cells in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45, 1187–1193 (2006).

Corcione, A. et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood 107, 367–372 (2006).

Kubo, S. et al. E-prostanoid (EP)2/EP4 receptor-dependent maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells and induction of helper T2 polarization. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 309, 1213–1220 (2004).

Shinomiya, S. et al. Regulation of TNFα and interleukin-10 production by prostaglandins I2 and E2: studies with prostaglandin receptor–deficient mice and prostaglandin E-receptor subtype-selective synthetic agonists. Biochem. Pharmacol. 61, 1153–1160 (2001).

Hata, A.N. & Breyer, R.M. Pharmacology and signaling of prostaglandin receptors: multiple roles in inflammation and immune modulation. Pharmacol. Ther. 103, 147–166 (2004).

Le Blanc, K. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. Lancet 371, 1579–1586 (2008).

Miyaji, T. et al. Ethyl pyruvate decreases sepsis-induced acute renal failure and multiple organ damage in aged mice. Kidney Int. 64, 1620–1631 (2003).

Yasuda, H., Yuen, P.S., Hu, X., Zhou, H. & Star, R.A. Simvastatin improves sepsis-induced mortality and acute kidney injury via renal vascular effects. Kidney Int. 69, 1535–1542 (2006).

Imai, Y., Ibata, I., Ito, D., Ohsawa, K. & Kohsaka, S. A novel gene iba1 in the major histocompatibility complex class III region encoding an EF hand protein expressed in a monocytic lineage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 224, 855–862 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank M.J. Brownstein for continuous advice and discussions; J. M. Weiss (NCI, NIH) for supplying the Ifng−/− mice; A. Keane-Myers (NIAID) for supplying the Il10−/− mice; Christophe Cataisson (NCI) for supplying the Tnfrsf1a−/− and Tnfrsf1b−/− mice; T. Merkel (US Food and Drug Administration) for supplying the Tlr4−/− and Myd88−/− mice; K. Holmbeck and L. Szabova (NIDCR) for the FVB/NJ mouse cells; and I. Szalayova and S. Key (NIDCR) for their superb technical help. The research was supported by the intramural programs of the NIDCR and the NIDDK, NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.N., A.L., P.S.T.Y., R.A.S. and E.M. formulated the basic hypotheses and experimental design; K.N., A.L., E.M., P.S.T.Y. and R.A.S. collected and evaluated data on survival and organ injury; K.N. and A.L. performed the in vivo experiments; A.L., P.S.T.Y., A.P., K.D., K.L. and X.H. assisted in the in vivo experiments and histology; P.G.R. consulted on BMSC biology; K.N. formulated the molecular mechanism hypothesis and designed and performed in vitro and ex vivo assays; B.H.K. helped to test the involvement of the prostaglandin receptors; J.M.B. and B.M. contributed to testing the involvement of COX2; B.M. performed the measurements for tissue peroxidase; I.J. performed FACS experiments; E.M. wrote the initial manuscript and prepared the figures; all of the authors edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figs. 1–5, Supplementary Table 1 and Suppmenentary Methods (PDF 1030 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Németh, K., Leelahavanichkul, A., Yuen, P. et al. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E2–dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat Med 15, 42–49 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.1905

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.1905

This article is cited by

-

Lipopolysaccharide alters VEGF-A secretion of mesenchymal stem cells via the integrin β3-PI3K-AKT pathway

Molecular & Cellular Toxicology (2024)

-

Dose-specific efficacy of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in septic mice

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2023)

-

Rapid and effective preparation of clonal bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cell sheets to reduce renal fibrosis

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Current perspectives on mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for graft versus host disease

Cellular & Molecular Immunology (2023)

-

Cell-based therapies for neurological disorders — the bioreactor hypothesis

Nature Reviews Neurology (2023)