Abstract

Microglia and other tissue-resident macrophages within the central nervous system (CNS) have essential roles in neural development, inflammation and homeostasis. However, the molecular pathways underlying their development and function remain poorly understood. Here we report that mice deficient in NRROS, a myeloid-expressed transmembrane protein in the endoplasmic reticulum, develop spontaneous neurological disorders. NRROS-deficient (Nrros−/−) mice show defects in motor functions and die before 6 months of age. Nrros−/− mice display astrogliosis and lack normal CD11bhiCD45lo microglia, but they show no detectable demyelination or neuronal loss. Instead, perivascular macrophage-like myeloid cells populate the Nrros−/− CNS. Cx3cr1-driven deletion of Nrros shows its crucial role in microglial establishment during early embryonic stages. NRROS is required for normal expression of Sall1 and other microglial genes that are important for microglial development and function. Our study reveals a NRROS-mediated pathway that controls CNS-resident macrophage development and affects neurological function.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Accession codes

Primary accessions

Gene Expression Omnibus

Referenced accessions

ArrayExpress

Gene Expression Omnibus

References

Hanisch, U.K. & Kettenmann, H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 1387–1394 (2007).

Aguzzi, A., Barres, B.A. & Bennett, M.L. Microglia: scapegoat, saboteur, or something else? Science 339, 156–161 (2013).

Prinz, M. & Priller, J. Microglia and brain macrophages in the molecular age: from origin to neuropsychiatric disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 300–312 (2014).

Ransohoff, R.M. & Cardona, A.E. The myeloid cells of the central nervous system parenchyma. Nature 468, 253–262 (2010).

Wu, Y., Dissing-Olesen, L., MacVicar, B.A. & Stevens, B. Microglia: dynamic mediators of synapse development and plasticity. Trends Immunol. 36, 605–613 (2015).

Miron, V.E. et al. M2 microglia and macrophages drive oligodendrocyte differentiation during CNS remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1211–1218 (2013).

Parkhurst, C.N. et al. Microglia promote learning-dependent synapse formation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Cell 155, 1596–1609 (2013).

Nimmerjahn, A., Kirchhoff, F. & Helmchen, F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science 308, 1314–1318 (2005).

Heneka, M.T., Kummer, M.P. & Latz, E. Innate immune activation in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 463–477 (2014).

Prinz, M., Priller, J., Sisodia, S.S. & Ransohoff, R.M. Heterogeneity of CNS myeloid cells and their roles in neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 1227–1235 (2011).

Perdiguero, E.G. et al. The origin of tissue-resident macrophages: when an erythro-myeloid progenitor is an erythro-myeloid progenitor. Immunity 43, 1023–1024 (2015).

Ginhoux, F. et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science 330, 841–845 (2010).

Kierdorf, K. et al. Microglia emerge from erythromyeloid precursors via Pu.1- and Irf8-dependent pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 273–280 (2013).

Schulz, C. et al. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science 336, 86–90 (2012).

Chen, S.K. et al. Hematopoietic origin of pathological grooming in Hoxb8 mutant mice. Cell 141, 775–785 (2010).

Bruttger, J. et al. Genetic cell ablation reveals clusters of local self-renewing microglia in the mammalian central nervous system. Immunity 43, 92–106 (2015).

Goldmann, T. et al. Origin, fate and dynamics of macrophages at central nervous system interfaces. Nat. Immunol. 17, 797–805 (2016).

Butovsky, O. et al. Identification of a unique TGF-β-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 131–143 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. IL-34 is a tissue-restricted ligand of CSF1R required for the development of Langerhans cells and microglia. Nat. Immunol. 13, 753–760 (2012).

Greter, M. et al. Stroma-derived interleukin-34 controls the development and maintenance of langerhans cells and the maintenance of microglia. Immunity 37, 1050–1060 (2012).

Beers, D.R. et al. Wild-type microglia extend survival in PU.1 knockout mice with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 16021–16026 (2006).

Minten, C., Terry, R., Deffrasnes, C., King, N.J. & Campbell, I.L. IFN regulatory factor 8 is a key constitutive determinant of the morphological and molecular properties of microglia in the CNS. PLoS One 7, e49851 (2012).

Buttgereit, A. et al. Sall1 is a transcriptional regulator defining microglia identity and function. Nat. Immunol. 17, 1397–1406 (2016).

Noubade, R. et al. NRROS negatively regulates reactive oxygen species during host defence and autoimmunity. Nature 509, 235–239 (2014).

Altuntas, C.Z. et al. Bladder dysfunction in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 203, 58–63 (2008).

Constantinescu, C.S., Farooqi, N., O'Brien, K. & Gran, B. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) as a model for multiple sclerosis (MS). Br. J. Pharmacol. 164, 1079–1106 (2011).

Pekny, M. & Pekna, M. Astrocyte reactivity and reactive astrogliosis: costs and benefits. Physiol. Rev. 94, 1077–1098 (2014).

Ito, D. et al. Microglia-specific localisation of a novel calcium binding protein, Iba1. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 57, 1–9 (1998).

Graeber, M.B., Streit, W.J., Kiefer, R., Schoen, S.W. & Kreutzberg, G.W. New expression of myelomonocytic antigens by microglia and perivascular cells following lethal motor neuron injury. J. Neuroimmunol. 27, 121–132 (1990).

Zamanian, J.L. et al. Genomic analysis of reactive astrogliosis. J. Neurosci. 32, 6391–6410 (2012).

Hickman, S.E. et al. The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1896–1905 (2013).

Ford, A.L., Goodsall, A.L., Hickey, W.F. & Sedgwick, J.D. Normal adult ramified microglia separated from other central nervous system macrophages by flow cytometric sorting. Phenotypic differences defined and direct ex vivo antigen presentation to myelin basic protein-reactive CD4+ T cells compared. J. Immunol. 154, 4309–4321 (1995).

Mizutani, M. et al. The fractalkine receptor but not CCR2 is present on microglia from embryonic development throughout adulthood. J. Immunol. 188, 29–36 (2012).

Greter, M., Lelios, I. & Croxford, A.L. Microglia versus myeloid cell nomenclature during brain inflammation. Front. Immunol. 6, 249 (2015).

Goldmann, T. et al. A new type of microglia gene targeting shows TAK1 to be pivotal in CNS autoimmune inflammation. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1618–1626 (2013).

Andersen, J.K. Oxidative stress in neurodegeneration: cause or consequence? Nat. Med. 10 (Suppl.), S18–S25 (2004).

Banci, L. et al. SOD1 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: mutations and oligomerization. PLoS One 3, e1677 (2008).

Zeisel, A. et al. Brain structure. Cell types in the mouse cortex and hippocampus revealed by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 347, 1138–1142 (2015).

Rivest, S. Molecular insights on the cerebral innate immune system. Brain Behav. Immun. 17, 13–19 (2003).

Wang, Y. et al. TREM2 lipid sensing sustains the microglial response in an Alzheimer's disease model. Cell 160, 1061–1071 (2015).

Lou, N. et al. Purinergic receptor P2RY12-dependent microglial closure of the injured blood-brain barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1074–1079 (2016).

Cardona, A.E. et al. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 917–924 (2006).

Nandi, S. et al. The CSF-1 receptor ligands IL-34 and CSF-1 exhibit distinct developmental brain expression patterns and regulate neural progenitor cell maintenance and maturation. Dev. Biol. 367, 100–113 (2012).

Roumier, A. et al. Impaired synaptic function in the microglial KARAP/DAP12-deficient mouse. J. Neurosci. 24, 11421–11428 (2004).

Wakselman, S. et al. Developmental neuronal death in hippocampus requires the microglial CD11b integrin and DAP12 immunoreceptor. J. Neurosci. 28, 8138–8143 (2008).

Matcovitch-Natan, O. et al. Microglia development follows a stepwise program to regulate brain homeostasis. Science 353, aad8670 (2016).

Zusso, M. et al. Regulation of postnatal forebrain amoeboid microglial cell proliferation and development by the transcription factor Runx1. J. Neurosci. 32, 11285–11298 (2012).

Marden, J.J. et al. Redox modifier genes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2913–2919 (2007).

Zhang, D., Hu, X., Qian, L., O'Callaghan, J.P. & Hong, J.S. Astrogliosis in CNS pathologies: is there a role for microglia? Mol. Neurobiol. 41, 232–241 (2010).

Gurney, M.E. et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science 264, 1772–1775 (1994).

Georgiades, P. et al. VavCre transgenic mice: a tool for mutagenesis in hematopoietic and endothelial lineages. Genesis 34, 251–256 (2002).

Hanson, J.E. et al. Chronic GluN2B antagonism disrupts behavior in wild-type mice without protecting against synapse loss or memory impairment in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. J. Neurosci. 34, 8277–8288 (2014).

Srinivasan, K. et al. Untangling the brain's neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative transcriptional responses. Nat. Commun. 7, 11295 (2016).

Wu, T.D. & Nacu, S. Fast and SNP-tolerant detection of complex variants and splicing in short reads. Bioinformatics 26, 873–881 (2010).

Love, M.I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Hochberg, Y. & Benjamini, Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat. Med. 9, 811–818 (1990).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106 (2010).

Morgan, K., Kharas, M., Dzierzak, E. & Gilliland, D.G. Isolation of early hematopoietic stem cells from murine yolk sac and AGM. J. Vis. Exp. 16, e789 (2008).

Sachs, H.H., Bercury, K.K., Popescu, D.C., Narayanan, S.P. & Macklin, W.B. A new model of cuprizone-mediated demyelination/remyelination. ASN Neuro 6, 1–16 (2014).

Brey, E.M. et al. Automated selection of DAB-labeled tissue for immunohistochemical quantification. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 51, 575–584 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Srinivasan and D. Hansen for assistance with flow cytometry–purified brain cells and fluidigm analysis; I. Peng for assistance with bone marrow transfer; B. Lauffer and P. Steiner for advice and help with microglia isolation and culture; C. Le Pichon, S. Dominguez and M. Weber for advice with behavioral studies; Z. Modrusan, C. Ha, J. Stinson and J. Guillory for assistance with RNA-seq; L. Diehl and P. Caplazi for advice and help with histopathological studies; and C. Allen, M. Thayer, M. Long, M. Lamoureux, T. Scholls and the Genentech Lab Animals facility for help and support with mouse colonies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.W. and W.O. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. K.W., R.N., P.M., N.O. and O.F. performed experiments. R.N., P.M. and R.P. edited the manuscript. J.A.H. and B.A.F. analyzed RNA-seq data. K.W., P.M. and K.S.-L. designed experiments.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors are current or previous employees of Genentech.

Integrated supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1 Nrros-/- mice show distended bladder and normal relative mass of major organs.

Representative H&E stained images of (a - b) bladder (bar = 500 μm), (c - d) ureter, (e - f) renal papillary epithelium (bar = 100 μm) and (g-h) renal glomerulus (bar = 50 μm) from Nrros+/+ and Nrros-/- animals. Graphs depicting the mass of gastrocnemius (i), tibialis (j), brain (k) and kidney (l) as percent body weight in Nrros+/+ and Nrros-/- animals. Arrow, outer smooth muscle wall; *, transitional epithelium. N ≥ 8. Error bar: ± SEM. Animals were 13 - 15 weeks old.

Supplementary Figure 2 Absence of immune infiltration and neurodegenerative signs in Nrros−/− mice.

Representative images of spinal cord cross sections from Nrros+/+ and Nrros-/- animals stained with (a) H&E (bar = 50 μm), (d) Nissl (bar = 500 μm) or (e) Luxol fast blue (bar = 1 mm). (b) Survival curve (n = 10) and (c) wire hang from WT and Nrros-/-Rag2-/- animals (12 - 14 weeks old; n = 5). Quantification of (f) number of axons per area, (g) total number of axons and (h) percent axons with indicated lumen area from p-Phenylenediamine staining on cross sections of sciatic nerve (n = 8). 15-week old Nrros+/+ and Nrros-/-animals are shown. Error bar: ± SEM. ***P < 0.001. Log rank test (b), One-way ANOVA (c), unpaired Student’s t-test (f - h).

Supplementary Figure 3 Signs of astrogliosis and altered expression of microglia signature genes in Nrros−/− brains.

RNA-seq comparing expression of whole brains from Nrros+/+ and Nrros-/- mice. Expression levels of (a - d) astrogliosis and (e - i) microglial markers. Itam (CD11b); Emr1 (F4/80). N = 5. (j) Full Western blot for protein expression of NRROS in the indicated cell types from WT brain as shown in Figure 3e. Actin as loading control. (k – p) Representative histograms of markers indicated in CD11b+ cells from Nrros+/+ and Nrros-/- brains. N = 3. Error bar: ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Unpaired Students’ t-test.

Supplementary Figure 4 Loss of Nrros from resident CNS macrophages but not peripheral myeloid cells causes neurological disorders.

(a - b) RT-qPCR analysis for Nrros expression in CD11b+ cells isolated from the brains of mice of the indicated genotype. Performance of (c - g) Nrrosfl/flVav-cre or (h - l) Nrrosfl/flLyz2-cre mice in rotarod test at (c, h) pretraining (9-week old), (d, i) fixed and (e, j) accelerating condition. S, session; T, trial. (f, k) Total beam breaks and (g, l) percent center beam breaks at open field tests. Animals were 10-11-week old unless specified otherwise. N = 16. (m-o) Nrros+/+ (WT) and Nrros-/- (KO) mice were sub lethally irradiated and reconstituted with donor marrow from either WT or KO mice (n = 15, 18, 14, 10). (m) Survival curve of WT and KO recipients grafted with indicated bone marrow stem cells. Quantification of percent engraftment in the blood (n) and brains (o) of these animals (n = 3). Error bar: ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (m) Log-rank test; all other analyses, unpaired Student’s t-test. ND, not determined.

Supplementary Figure 5 Loss of NOX2 fails to rescue neurological phenotype in Nrros−/− mice.

(a) mRNA expression of Cybb (NOX2) in Nrros+/+ and Nrros-/- brains from RNA-seq. (b - f) Performance of Nrros+/+, Nrros-/-, Cybb-/- and Nrros-/-Cybb-/- in rotarod test at (b) pretraining (9 weeks), (c) fixed and (d) accelerating conditions. S, session; T, trial. (e) Total beam breaks and (f) percent center beam breaks in open field test. Animals were 11-week old unless specified otherwise (n = 16). Error bar: ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. One-way ANOVA, (c, e, f); Unpaired Student’s t-test (a - c).

Supplementary Figure 6 Efficiency of Nrros deletion in Nrrosfl/flCx3cr1CreER mice.

Relative expression of Nrros in (a) E14.5 YFP+ FACS-sorted cells and (b) E21 CD11b+ cells from brains of E10.5 tamoxifen-treated animals. (c) Relative expression of Nrros in CD11b+ cells from the brain at week 9 after tamoxifen treatment at week 3. N = 3. Error bar: ± SEM. *P < 0.05. Unpaired Student’s t-test.

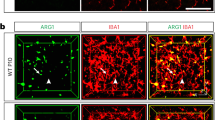

Supplementary Figure 7 Altered macrophage population in Nrros−/− brains.

(a) Gating strategy for FACS-sorting of microglia, PVM and PLCs. Expression level of (b) Nrros, (c - k) microglial, (l - o) PVM surface markers from RNA-seq comparing Nrros+/+ (WT) microglia, PVM and Nrros-/- PLCs (n = 3). Error bar: ± SEM. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Unpaired Student’s t-test. 12-week old animals were used.

Supplementary Figure 8 Nrros−/− PLCs do not resemble activated microglia.

(a - c) Gene expression of indicated cytokines from RNA-seq of Nrros+/+ (WT) microglia, PVM and Nrros-/- (KO) PLCs (n = 3). (d - f) Basal cytokine levels secreted by cultured myeloid cells isolated from WT and KO brains. (g) Heat map showing top 30 differentially expressed genes between WT PVM and KO PLCs. N = 3. Error bar: ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Unpaired Student’s t-test. 12-week old animals were used.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–8 (PDF 2152 kb)

Supplementary Table 1

Differentially expressed genes in WT and Nrros−/− brains. (XLSX 8 kb)

Supplementary Table 2

Top 30 differentially expressed genes in WT PVMs and Nrros−/− PLCs. (XLSX 5 kb)

Supplementary Table 3

Differentially expressed gene in Nrros−/− PLCs and Sall1−/− microglia. (XLSX 11 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, K., Noubade, R., Manzanillo, P. et al. Mice deficient in NRROS show abnormal microglial development and neurological disorders. Nat Immunol 18, 633–641 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3743

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3743

This article is cited by

-

Mechanisms of myeloid cell entry to the healthy and diseased central nervous system

Nature Immunology (2023)

-

APOE4 impairs the microglial response in Alzheimer’s disease by inducing TGFβ-mediated checkpoints

Nature Immunology (2023)

-

Involvement of FoxO1, Sp1, and Nrf2 in Upregulation of Negative Regulator of ROS by 15d-PGJ2 Attenuates H2O2-Induced IL-6 Expression in Rat Brain Astrocytes

Neurotoxicity Research (2022)

-

Brain perivascular macrophages contribute to the development of hypertension in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats via sympathetic activation

Hypertension Research (2020)

-

The influence of environment and origin on brain resident macrophages and implications for therapy

Nature Neuroscience (2020)