Abstract

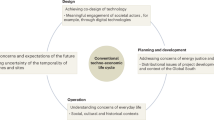

Issues concerning the social acceptance of wind energy are major challenges for policy-makers, communities and wind developers. They also impact the legitimacy of societal decisions to pursue wind energy. Here we set out to identify and assess the factors that lead to wind energy disputes in Ontario, Canada, a region of the world that has experienced a rapid increase in the development of wind energy. Based on our expertise as a group comprising social scientists, a community representative and a wind industry advocate engaged in the Ontario wind energy situation, we explore and suggest recommendations based on four key factors: socially mediated health concerns, the distribution of financial benefits, lack of meaningful engagement and failure to treat landscape concerns seriously. Ontario's recent change from a feed-in-tariff-based renewable electricity procurement process to a competitive bid process, albeit with more attention to community engagement, will only partially address these concerns.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Renewables 2014: Global Status Report 67 (Renewable Energy Network, 2014).

Global Statistics (Global Wind Energy Council, 2015); http://go.nature.com/mMkeww

Ontario's Renewable Energy Story – Policy Landscape (Ontario Power Authority, 2014); http://go.nature.com/ISXCtQ

Batel, S., Devine-Wright, P. & Tangeland, T. Social acceptance of low carbon energy and associated infrastructures: A critical discussion. Energy Policy 58, 1–5 (2013).

Bell, D., Gray, T. & Haggett, C. The ‘social gap’ in wind farm siting decisions: Explanations and policy responses. Environ. Polit. 14, 460–477 (2005).

Wolsink, M. Wind power implementation: The nature of public attitudes: Equity and fairness instead of ‘backyard motives’. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 11, 1188–1207 (2007).

Wustenhagen, R., Wolskink, M. & Burer, J. Social acceptance of renewable energy innovation: An introduction to the concept. Energy Policy 35, 2683–2691 (2007).

Social and community aspects of wind power in Ontario. www.queenswindworkshop.org (2015).

Fast, S. Social acceptance of renewable energy: Trends, concepts, geographies. Geography Compass 7, 853–856 (2013).

Toke, D., Breukers, S. & Wolsink, M. Wind power deployment outcomes: How can we account for the differences? Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 12, 1129–1147 (2008).

New law will keep NIMBY-ism from stopping green projects: Ont. premier CBC News (10 February 2009); http://go.nature.com/ijhvq1

Hill, S. & Knott, J. Too close for comfort: social controversies surrounding wind farm noise setback policies in Ontario. Renew. Energy Law Policy 2, 153–168 (2010).

Wolsink, M. Wind power and the NIMBY-myth: institutional capacity and the limited significance of public support. Renew. Energy 21, 49–64 (2000).

Deignan, B., Harvey, B. & Hoffman-Goetz, L. Fright factors about wind turbines and health in Ontario newspapers before and after the Green Energy Act. Health Risk Soc. 15, 234–250 (2013).

Songsore, E. & Buzzelli, M. Social responses to wind energy development in Ontario: the influence of health risk perceptions and associated concerns. Energy Policy 69, 285–296 (2014).

Walker, C., Baxter, J. & Oulette, D. Beyond rhetoric to understanding determinants of wind turbine support and conflict in two Ontario, Canada communities. Environ. Plann. A 43, 730–745 (2014).

Walker, C., Baxter, J. & Oulette, D. Adding insult to injury: the development of psychosocial stress in Ontario wind turbine communities. Soc. Sci. Med. 46, 730–745 (2014).

Bowdler, D. Wind turbine syndrome — an alternative view. Acoust. Aust. 40, 67–69 (2012).

Pederson, E. & Waye, K. P. Wind turbine noise, annoyance and self-reported health and well-being in different living environments. Occup. Environ. Med. 64, 480–486 (2007).

Shrader-Frechette, K. in Scientific Uncertainty and Environmental Problem Solving (ed. Lemons, J. ) 12–39 (Blackwell, 1996).

Taubes, G. & Mann, C. Epidemiology faces its limits. Science 269, 164–169 (1995).

Carolan, M. S. The precautionary principle and traditional risk assessment rethinking how we assess and mitigate environmental threats. Org. Environ. 20, 5–24 (2007).

King, A. The Potential Health Impact of Wind Turbines: Chief Medical Officer of Health (CMOH) Report (Ontario Ministry of Health, 2010).

Colby, D. et al. Wind Turbine Sound and Health Effects: An Expert Panel Review (Canadian Wind Energy Association, 2009).

Renewable energy technologies and health, summary of activities — Year 4. http://go.nature.com/2S2wgd (2014).

Christidis, T. Research findings from the Ontario Research Chair in renewable energy technologies and health. http://go.nature.com/uYzjX2 (2015).

Nissenbaum, M. A., Aramini, J. & Hanning, C. Effects of industrial wind turbine noise on sleep and health. Noise Health 14, 237–243 (2012).

Michaud, D. Health and well-being related to wind turbine noise exposure: summary of results. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 137, 2368–2368 (2015).

Chapman, S., St. George, A., Walker, K. & Cakic, V. The pattern of complaints about Australian wind farms does not match the establishment and distribution of turbines: support for the psychogenic, ‘communicated disease’ hypothesis. PLoS ONE 8, e76584 (2013).

Shepherd, D., McBride, D., Welch, D., Dirks, K. N. & Hill, E. M. Evaluating the impact of wind turbine noise on health-related quality of life. Noise Health 15, 333–339 (2011).

Christidis, T. & Law, J. Annoyance, health effects, and wind turbines: exploring Ontario's planning processes. Can. J. Urban Res. 21, 81–105 (2012).

Cowell, R. Wind power, landscape and strategic, spatial planning — the construction of ‘acceptable locations’ in Wales. Land Use Policy 27, 222–232 (2010).

Ek, K. & Persson, L. Wind farms — where and how to place them? A choice experiment approach to measure consumer preferences for characteristics of wind farm establishments in Sweden. Ecol. Econ. 105, 193–203 (2014).

Musall, F. D. & Kuik, O. Local acceptance of renewable energy — a case study from southeast Germany. Energy Policy 39, 3252–3260 (2011).

Warren, C. R. & McFadyen, M. Does community ownership affect public attitudes to wind energy? A case study from south-west Scotland. Land Use Policy 27, 204–213 (2010).

Frontenac Islands amenities agreement. http://go.nature.com/um2Dvx (2006).

Community vibrancy fund agreement, Haldimand County. http://go.nature.com/J2rIhT (2012).

Cass, N., Walker, G. & Devine-Wright, P. Good neighbours, public relations and bribes: the politics and perceptions of community benefit provision in renewable energy development in the UK. J. Environ. Policy Plann. 12, 255–275 (2010).

Strachan, P., Cowell, R., Ellis, G., Sherry-Brennan, F. & Toke, D. Promoting community renewable energy in a corporate energy world. Sust. Dev. 23, 96–109 (2015).

Winfield, M. & Dolter, B. Energy, economic and environmental discourses and their policy impact: the case of Ontario's Green Energy and Green Economy Act. Energy Policy 68, 423–435 (2014).

Guide for landowners with agricultural farming operations. Prowind Canadahttp://go.nature.com/WyV9ft (2009).

Technical Guide to Renewable Energy Approvals (Ontario Ministry of the Environment, 2013).

Arnstein, S. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. I. Planners 35, 216–224 (1969).

Hindmarsh, R. & Matthews, C. Deliberative speak at the turbine face: community engagement, wind farms, and renewable energy transitions, in Australia. J. Environ. Policy Plann. 10, 217–232 (2008).

Devine-Wright, P. in Renewable Energy and the Public: From NIMBY to Participation (ed. Devine-Wright, P. ) 57–70 (Earthscan, 2011).

Jami, A. N. J. & Marsh, P. The role of public participation in identifying stakeholder synergies in wind power project development: the case study of Ontario, Canada. Renew. Energy 68, 194–202 (2014).

Shaw, K. et al. Conflicted or constructive? Exploring community responses to new energy developments in Canada. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 8, 41–51 (2015).

Mulvhill, P., Winfield, M. & Etcheverry, J. Strategic environmental assessment and advanced renewable energy in Ontario: Moving forward or blowing in the wind? J. Environ. Assoc. Policy Manag. 15, 134006 (2013).

Devine-Wright, P. Beyond NIMBYism: towards an integrated framework for understanding public perceptions of wind energy. Wind Energy 8, 125–139 (2005).

Phadke, R. Resisting and reconciling big wind: middle landscape politics in the new American West. Antipode 43, 754–766 (2011).

Wolsink, M. Planning of renewables schemes: deliberative and fair decision-making on landscape issues instead of reproachful accusations of non-cooperation. Energy Policy 35, 2692–2704 (2007).

Baxter, J., Morzaria, R. & Hirsch, J. A case-control study of support/opposition to wind turbines: perceptions of health risk, economic benefits, and community conflict. Energy Policy 61, 931–943 (2013).

Cultural heritage landscapes — an introduction. Ontario Heritage Trusthttp://go.nature.com/rgrIwk (2012).

Amherst Island Wind Energy Project Heritage Assessment (Stantec Consulting, 2013).

Driver, L. The White Pines Wind Project: a precedent-setting case for the protection of cultural heritage landscapes in Ontario. http://go.nature.com/Km6ewc (2015).

Fast, S. & Mabee, W. Trust-building and place-making: the influence of policy on host community responses to wind farms. Energy Policy 81, 27–37 (2015).

Stedman, R. Is it really just a social construction? The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Soc. Nat. Resour. 16, 671–685 (2003).

Vorkinn, M. & Riese, H. Environmental concern in a local context: the significance of place attachment. Environ. Behav. 33, 249–263 (2001).

Devine-Wright, P. & Howes, Y. Disruption to place attachment and the protection of restorative environments: a wind energy case study. J. Environ. Psychol. 30, 271–280 (2010).

Raven, R. P. J. M., Mourik, R. M., Feenstra, C. F. J. & Heiskanen, E. Modulating societal acceptance in new energy projects: towards a toolkit methodology for project managers. Energy 34, 564–574 (2009).

Szarka, J., Cowell, R., Ellis, G., Strachan, P. & Warren, C. Learning from Wind Power: Governance, Societal and Policy Perspectives on Sustainable Energy (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

Mabee, W., Mannion, J. & Carpenter, T. Comparing the feed-in tariff incentives for renewable electricity in Ontario and Germany. Energy Policy 40, 480–489 (2012).

Morris, C. & Pehnt, M. Energy Transition: The German Energiewende (Heinrich Böll Foundation, 2012).

Stokes, L. C. Electoral backlash against climate policy: a natural experiment on retrospective voting and local resistance to public policy. Am. J. Pol. Sci. http://doi.org/bbnt (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fast, S., Mabee, W., Baxter, J. et al. Lessons learned from Ontario wind energy disputes. Nat Energy 1, 15028 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2015.28

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2015.28

This article is cited by

-

Facilitating developments of solar photovoltaic power and offshore wind power to achieve carbon neutralization: an evolutionary game theoretic study

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Scenicness assessment of onshore wind sites with geotagged photographs and impacts on approval and cost-efficiency

Nature Energy (2021)

-

From Project Impacts to Strategic Decisions: Recurring Issues and Concerns in Wind Energy Environmental Assessments

Environmental Management (2021)

-

A strong relative preference for wind turbines in the United States among those who live near them

Nature Energy (2019)

-

Energy justice: Participation promotes acceptance

Nature Energy (2017)