Abstract

Bicyclo[1.1.0]but-1(2)-ene (BBE), one of the smallest bridgehead alkenes and C4H4 isomers, exists theoretically as a reactive intermediate, but has not been observed experimentally. Here we successfully synthesize the silicon analogue of BBE, tetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]but-1(2)-ene (Si4BBE), in a base-stabilized form. The results of X-ray diffraction analysis and theoretical study indicate that Si4BBE predominantly exists as a zwitterionic structure involving a tetrasilahomocyclopropenylium cation and a silyl anion rather than a bicyclic structure with a localized highly strained double bond. The reaction of base-stabilized Si4BBE with triphenylborane affords the [2+2] cycloadduct of Si4BBE and the dimer of an isomer of Si4BBE, tetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]butan-2-ylidene (Si4BBY). The facile isomerization between Si4BBE and Si4BBY is supported by theoretical calculations and trapping reactions. Structure and properties of a heavy analogue of the smallest bridgehead alkene are disclosed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bridgehead alkenes have a strained doubly bonded carbon at the bridgehead positions in the bicyclic skeleton. Their syntheses, highly strained structures and high reactivities have widely attracted the attention of both theoretical and experimental chemists since the pioneering work of Bredt1,2,3,4,5. Bicyclo[1.1.0]but-1(2)-ene (BBE, E=C, Fig. 1a) is a bridgehead alkene with the smallest number of bridge atoms and several possible canonical structures containing a strained double bond2, even though BBE has been considered to be an exceptional bridgehead alkene (‘zero-bridge alkene’) because of the lack of a twisted double-bond geometry observed in typical bridgehead alkenes. Although BBE and its derivatives have been proposed as reactive intermediates6 and theoretically investigated as the isomers of C4H4 molecules present in important fundamental organic molecules such as tetrahedrane and cyclobutadiene7,8,9,10,11, the synthesis and experimental observation of BBE and its derivatives have not been reported yet.

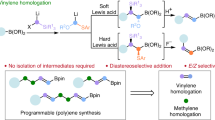

(a) BBE and its silicon analogue (Si4BBE). (b) Synthesis of DMAP-stabilized Si4BEE (1˙DMAP) (R=SiMe3) and the dimer of Si4BBE (4). (c) Reaction of 1˙DMAP˙DMAP with triphenylborane (R=SiMe3). (d) A possible equilibrium between Si4BBE 1 and tetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]butan-2-ylidene (Si4BBY) 1′ (R=SiMe3). (e) Reactions of disilene 8 supporting generation of 1 and 1′ (R=SiMe3).

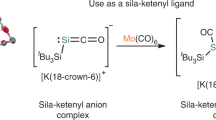

Recently, the silicon analogues of alkenes and structurally related unsaturated organic compounds that have never been experimentally observed or synthesized previously such as pentasilaspiropentadiene12, tetrasilacyclobutadiene with a planar rhombic charge-separated structure13, trisilavinylcarbene14, silavinylidene15, Si(0)2 (ref. 16) and isomers of hexasilabenzene17,18 have been synthesized as isolable molecules by taking advantage of kinetic stabilization and/or stabilization by base coordination. Their structures and properties have contributed to further understanding of the bonding and structures of organic and heavy main group element π-electron compounds. Among the Si4R4 species, tetrasilatetrahedrane19 and tetrasilacylobutadiene13 have been isolated. However, the tetrasila version of BBE (Si4BBE, E=Si, Fig. 1a) has been only theoretically investigated as one of the isomers among the Si4R4 molecules20,21, whereas it’s detailed molecular and electronic structures and reactivity remain elusive.

In this study we report the synthesis of Si4BBE 1, which was stabilized by coordinating to 4-(N,N-dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) (1·DMAP). The results of X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis and theoretical study indicate that Si4BBE predominantly exists as a zwitterionic structure containing a tetrasilahomocyclopropenylium cation22 and a silyl anion, rather than a bicyclic structure with a localized double bond. The elimination of DMAP from 1·DMAP with BPh3 afforded the [2+2] cycloadduct of 1 (4) and the dimer of tetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]butan-2-ylidene (Si4BBY) 1′ (8), whose parent molecule was predicted as the global minimum on a Si4H4 surface20,21. These results indicate a reversible valence isomerization between 1 and 1′, which was supported by the thermal isomerization of 8 to 4 and reactions of 8 with SiCl4 and DMAP. Thus, the synthesis, structure, bonding and reactivity of a heavy analogue of the smallest bridgehead alkenes are reported.

Results

Thermolysis of hexaalkyltricyclo[2.1.0.01,3]pentasilane

Si4BBE 1 was initially suggested to be generated by the thermolysis of hexaalkyltricyclo[2.1.0.01,3]pentasilane 2, which was prepared in 63% yield by the reaction of the corresponding potassium trialkyldisilenide 3 (ref. 23) with 0.5 equiv. of SiCl4 (Figs 1b and 2a; for the detailed molecular structure of 2, see Supplementary Information), similar to the synthesis of Scheschkewitz’s hexaaryl derivative Tip6Si5 2′ (Tip=2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl)24. Compound 2 was isolated as reddish purple crystals at ambient temperature. However, heating 2 at 40 °C for 10 h in benzene afforded a mixture of pentacyclo[5.1.0.01,6.02,5.03,5]octasilane 4 and silene 5 (Fig. 1b), whereas Scheschkewitz24 observed an ion peak assignable to a cluster expansion product with formula Si7R6 during the measurement of the electron ionization mass spectrometry of 2′. Compound 4 was isolated as orange crystals in 61% yield and identified by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, mass spectrometry (MS), XRD analysis and elemental analysis (Fig. 2b). The results of XRD analysis indicate that the silicon skeleton of 4 has a four-membered ring fused by two tetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]butane units in a syn manner, which is a formal head-to-tail [2+2] cycloadduct of 1. Notably, the geometry around naked silicon atoms (silicon atoms without substituents), Si3 and Si6 atoms, in 4 are very far from the tetrahedral geometry similar to the naked silicon atoms in 2 and 2′: For Si3 atom, the angles Si1−Si3−Si2, Si2−Si3−Si4, Si4 –Si3−Si5 and Si1−Si3−Si5 are 60.98(3)°, 57.22(3)°, 94.29(4)° and 163.97(4)°, respectively, and for Si6 atom, the angles Si4−Si6−Si5, Si5−Si6−Si7, Si7−Si6−Si8 and Si4−Si6−Si8 are 94.81(4)°, 57.08(3)°, 60.08(3)° and 162.26(4)°, respectively. The transannular Si2–Si3 and Si6–Si7 bond distances in the terminal tetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]butane units, 2.4067(11) and 2.4177(11) Å, respectively, are within the range of Si–Si single bond distances. The 29Si chemical shifts of the naked Si, two (t-Bu)Si and RH2Si nuclei (RH2=1,1,4,4-tetrakis(trimethylsilyl)butan-1,4-diyl) are δ −26.8, (−18.4 and −5.5) and 24.6 p.p.m., respectively. As 5 is a thermal isomerization product of dialkylsilylene 6 (ref. 25), the generation of 1 and 6 was indicated by the thermolysis of 2.

(a) Tricyclo[2.1.0.01,3]pentasilane 2. (b) Pentacyclo[5.1.0.01,6.02,5.03,5]octasilane 4 (a dimer of Si4BBE 1). (c) DMAP-coordinate Si4BBE 1·DMAP. (d) Bi(tetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]butan-2-ylidene) 8 (a dimer of Si4BBY 1′). Thermal ellipsoids are shown at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Synthesis of 1·DMAP

To obtain monomeric Si4BBE 1, we investigated the thermolysis reaction in the presence of a Lewis base, because coordinating to a Lewis base may stabilize Si4BBE 1, similar to other unsaturated silicon compounds14,15,16,26. The reaction of 2 in the presence of 7.6 equiv. of DMAP, which is a typical Lewis base for unsaturated silicon compounds, at 40 °C for 5 h afforded an orange solution. The 1H NMR spectrum of the mixture indicated the existence of a new compound with 1 and DMAP units together, and 2-silyl-(N,N-dimethylamino)pyridine 7, which is a product of the reaction of silene 5 with DMAP. Removal of the volatiles from the reaction mixture and repeated recrystallization from hexane at −35 °C and then from benzene at room temperature afforded analytically pure 1·DMAP as orange crystals in 89% yield. The structure of 1·DMAP was determined by NMR spectroscopy, MS spectrometry, XRD analysis and elemental analysis.

X-ray analysis of 1·DMAP

The results of the XRD analysis of 1·DMAP indicate that the central Si4 ring has a folded structure with the dihedral angle Si2–Si1–Si3–Si4 of 127.03(2)° (Fig. 2c). The nitrogen atom of DMAP coordinates to Si2 atom with the Si2−N1 distance of 1.8764(14) Å, which is moderately longer than the typical Si−N distance (1.71–1.74 Å)27. The Si1 atom has no substituent and the Si1−Si3 distance is 2.6215(6) Å, which is considerably longer than those of known tetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]butanes (2.367–2.412 Å)28,29, but still shorter than the longest Si−Si distance reported so far (2.697 Å for (t-Bu)3SiSi(t-Bu)3)30. The endocyclic Si1–Si2 and Si2–Si3 bond distances, 2.2906(6) and 2.2556(6) Å, respectively, are between the typical Si−Si (ca. 2.36 Å)27 and Si=Si bond distances (2.118–2.289 Å)31,32, and close to those of N-heterocyclic carbene-coordinated cyclotrisilene (trisilacyclopropene) (2.2700(5)Å)26, indicating a significant double-bond character in Si1−Si2 and Si2−Si3 bonds. The geometry around Si2 is considerably pyramidalized with the sum of bond angles around Si2 (except the angles involving Si2−N1 bond) of 312.63(4)°, whereas that around Si3 is almost planar with the sum of bond angles around Si3 (except the bond angles involving Si1−Si3 bond), 359.30(4)°. The DMAP moiety exhibits a significant quinoid character. The C5−C6, C8−C9 and C7−N2 bond distances are 1.362(2), 1.359(2) and 1.343(2) Å, respectively, which are shorter than those of the corresponding bonds in free DMAP (1.375(4), 1.381(3) and 1.367(3) Å), whereas the other C−C and C−N bond distances (1.418(2)–1.419(2) and 1.358(2)–1.361(2) Å, respectively) in the pyridine ring of 1·DMAP are longer than those of free DMAP (1.403(3)–1.404(3) and 1.335(4)–1.337(3) Å, respectively)33.

Theoretical study of 1·DMAP and base-free 1

The comparison of the structural parameters and orbitals between 1·DMAP and base-free 1 obtained by the density functional theory calculations provided further insight into the bonding and structure of 1·DMAP and 1. The structure of 1·DMAP determined by XRD analysis was well reproduced by the optimized structure of 1·DMAP calculated at the M06-2X/6-31G(d) level (1·DMAPopt) (see Supplementary Fig. 40). The dihedral angle, Si2−Si1−Si3−Si4, of 1·DMAPopt is 124.72°, and the Si1−Si2, Si2−Si3, Si1−Si3 and Si1−N1 bond distances are 2.2865, 2.2441, 2.6174 and 1.9368 Å, respectively, which are very close to those of 1·DMAP. The structural parameters of base-free 1 optimized at the same level (1opt) slightly deviated from those of 1·DMAPopt (Fig. 3a). Similar to 1·DMAP, the four-membered ring of 1opt is folded with the dihedral angle Si4−Si1−Si3−Si2 of 121.89°. The Si1···Si3 distance of 2.849 Å is much longer than the longer end of Si−Si single bond (2.697 Å)30 and that of 1·DMAPopt (2.620 Å). The endocyclic Si1−Si2 and Si2−Si3 bond distances of 2.228 and 2.207 Å in 1opt, respectively, are within the range of Si=Si double bond (2.118–2.289 Å)31,32 and shorter than those of 1·DMAPopt (2.286 and 2.244 Å). The bond angle around the unsubstituted Si1 atom (Si4−Si1−Si2) is 85.2°. The geometries around Si2 and Si3 atoms are slightly pyramidalized with the sums of bond angles of 350.24° and 354.98°, respectively. These results indicate that on the coordination of DMAP, the Si1−Si2 and Si2−Si3 bond distances of 1 were elongated (2.286 and 2.244 Å), whereas the Si1−Si3 bond distance was shortened (2.620 Å). A similar elongation of Si=Si double bonds on the coordination of Lewis bases has been reported by Scheschkewitz et al.26

(a) Optimized structure of 1 (1opt) and selected bond lengths, Wiberg bond indices and the natural charges of 1opt at the M06-2X/6-31G(d) level. (b) Frontier Kohn–Sham orbitals of 1opt at the M06-2X/6-31G(d) level. (c) Frontier Kohn–Sham orbitals of 1˙DMAPopt. LUMO and LUMO+1 of 1˙DMAPopt are the anti-bonding π-orbitals of pyridine moiety in DMAP. (d) Important canonical structures of 1.

The frontier orbitals of 1opt and 1·DMAPopt are shown in Fig. 3b,c. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of 1opt is a lone pair orbital on Si1 with the contribution of a p-type orbital on Si3 atom (Fig. 3b), which is close to the orbital feature of the interbridgehead bond proposed for all-carbon bicyclo[1.1.0]but-1(2)ene7. The HOMO-1 orbital of 1 is an in-phase combination of π(Si1−Si2) orbital and a p-type orbital on Si3 atom. The lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of 1opt is an out-of-phase combination of π*(Si1−Si2) orbital and a p-type orbital on Si3 atom, and the LUMO+1 is an anti-bonding orbital between Si1 and Si3 atoms. The HOMO-1, LUMO and LUMO+1 orbitals resemble the frontier orbitals of those of tetrasilahomocyclopropenylium cation reported by Sekiguchi et al.22,34 These orbital features indicate that the zwitterionic resonance structure with tetrasilahomocyclopropenylium cation over the Si1–Si2–Si3 atom, and silyl anion on Si1 atoms (1z, Fig. 3d) contributes significantly to the electronic structure of 1opt. Very recently, a zwitterionic trisilahomoconjugative compound, a disilaoxaallyl zwitterion was reported by Scheschekwitz et al.35 The Wiberg bond indices (WBI) of the Si1−Si2 and Si2−Si3 bonds of 1opt are 1.34 and 1.34, respectively, which are larger than those of Si3−Si4 (1.02) and Si4−Si1 (0.88), respectively, whereas the WBI of Si1−Si3 bond is 0.51, indicating significant bonding interactions between the bridgehead silicon atoms, Si1 and Si3. The natural bonding orbital analysis of 1opt predicts a three-centred two-electron bond involving Si1 (28.3%), Si2 (35.8%) and Si3 (35.8%) with 1.84 electron and a lone pair on Si1 with 1.88 electron. These results are consistent with the resonance structure of 1z. The natural population analysis charges of Si1, Si2 and Si3 atoms are −0.02, +0.43 and +0.42, respectively, indicating that Si1−Si2 bond is considerably polar, which is consistent with the formation of head-to-tail cycloadduct 4. The coordination of DMAP on the Si2 atom of 1 can be rationalized by the positive charge on Si2 and sterically less congested geometry around Si2 compared with those around Si3, indicating that a canonical structure involving disilenylsilylene such as the III of Si4BBE in Fig. 1a is a less important contributor. Recently, Scheschkewitz and colleagues14 reported a base-stabilized disilenylsilylene in which the base coordinates to the two-coordinate silylene centre. At the M06-2X/6-31G(d) level, the coordination of DMAP to 1opt affording 1·DMAPopt was calculated to be exergonic at 298 K (ΔG298 K=−39.4 kJ mol−1), which is consistent with the experimental observation. The feature of the frontier orbitals of 1·DMAPopt resembles to that of 1opt (Fig. 3c). The WBI of the Si1−Si3 for 1·DMAPopt (0.73) is larger than that for 1opt (0.51), whereas those of the Si1−Si2 and Si2−Si3 for 1·DMAPopt (1.10 and 1.15) are smaller than those for 1opt (1.34 and 1.34). The structural change on the coordination of DMAP can be rationalized by the interactions between the lone pair orbital of nitrogen in DMAP and the LUMO of 1opt involving the bonding interactions between Si1 and Si3, and the anti-bonding interactions between Si1 and Si2, and between Si2 and Si3, resulting in a LUMO+3 orbital.

29Si NMR spectra of 1·DMAP

In benzene-d6, three 29Si resonances arising due to the ring silicon nuclei of 1·DMAP appeared at δ +84.5, +13.3 and −79.8 p.p.m., which were assigned to Si(t-Bu)(DMAP), SiRH2 and Si(t-Bu) silicon nuclei by 2D1H-29Si NMR HETCOR experiments. No resonance assignable to the naked silicon nuclei was observed probably because of the considerably long relaxation time of the 29Si nuclei. The assignment of the 29Si resonances are supported by the density functional theory calculations of 1·DMAPopt (+84.4 (Si(t-Bu)(DMAP)), −4.1 (SiRH2) and −105.1 (Si(t-Bu))) and the predicted 29Si chemical shift of the naked silicon is δ−108.6 p.p.m. These 29Si resonances indicate that 1·DMAP adopts a structure similar to that observed in the solid state.

Elimination of DMAP from 1·DMAP

The elimination of DMAP from 1·DMAP was investigated to generate free Si4BBE 1. When a benzene-d6 solution of 1·DMAP was treated with BPh3 at room temperature, the colour of the reaction mixture became green, and the NMR spectrum of the mixture indicated the formation of 4 (72% yield) and a disilene with two tetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]butane skeletons (8) (8% yield) (Fig. 1c). Disilene 8 is the dimer of Si4BBY (1′), which is an isomer of 1. After keeping the mixture for 48 h at room temperature, 4 was obtained in 78% yield, indicating the isomerization of 8 to 4. Disilene 8 was isolated as deep blue crystals during the reaction and its structure was determined by XRD analysis, NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 2d; for details, see Supplementary Information). The results indicate the formation of both 1 and 1′ by the reaction of 1·DMAP with BPh3, equilibrium between 1 and 1′ (Fig. 1d) and the dissociation of disilene 8 into 1′. These are supported by the reaction of disilene 8 with SiCl4 and DMAP affording a SiCl4 adduct of 1′ (9) and a DMAP adduct of 1 (1·DMAP) (Fig. 1e), respectively.

The facile isomerization between 1 and 1′ was supported by theoretical calculations. The Si4BBY (1′opt) was optimized as the local minimum at the M06-2X/6-31 G(d) level and 1′opt is lower in energy by 11.8 kJ mol−1 (298 K) than 1opt. Similar relative stability for the parent Si4H4 system has been theoretically predicted previously20,21. A concerted pathway involving the 1,2-migration of SiRH2 unit from Si1 to Si2 in 1 was predicted for the isomerization of 1opt to 1′opt and the calculated Gibbs energy of activation (298 K) for the isomerization was 69.6 kJ mol−1 (1′opt→1opt), which is enough for the reversible isomerization at room temperature to proceed. Although 1′opt is more stable than 1opt, the coordination of DMAP to 1opt (ΔG298 K=−4.0 kJ mol−1) is less exergonic than that for 1opt (ΔG298 K=−39.4 kJ mol−1) probably because of the reduced Lewis acidity of 1′ resulting from the donation of bridgehead Si–Si bond electrons to the vacant 3p orbitals of two-coordinate silylene centre. These results are consistent with the observation and isolation of 1·DMAP instead of 1′·DMAP.

The formation of 4 as the final product in the reaction of 1·DMAP with BPh3 and the facile dissociation of 8 were also supported by theoretical calculations. The optimized structures of 4 and 8 calculated at the M06-2X level (4opt and 8opt, respectively, see Supplementary Figs 43 and 44) reproduced well structural characteristics of 4 and 8 as determined by XRD analyses. Dimer 4opt was 53.5 kJ mol−1 more stable than 8opt and the dimerization of 1opt into 4opt was calculated to be considerably exergonic (ΔG298 K=−106.4 kJ mol−1) compared with that of 1′opt into 8opt (ΔG298 K=−52.9 kJ mol−1). The calculated bond dissociation enthalpy of the Si=Si bond of disilene 8opt, 108.5 kJ mol−1, was much lower than that of tetrasilyldisilene (Me3Si)2Si=Si(SiMe3)2 (330.6 kJ mol−1) at the M06-2X/6-311G(d) level (see Supplementary Tables 10 and 11), but close to that of (Me5C5)[(Me3Si)2N]Si=Si[N(SiMe3)2](C5Me5) (97.1 kJ mol−1, at the RI-BP86/TZVP level), which dissociates into the corresponding silylene in solution36. The relatively low bond dissociation enthalpy of 8opt can be mainly attributed to the stabilization of 1′opt by the donation of bridgehead Si–Si bond electrons to the vacant orbital of two-coordinate silicon centre similar to the π-donation of nitrogen atoms in amino-substituted silylenes. Although other multistep isomerization routes from 8 to 4 or the contribution of DMAP that can accelerate the dissociation of the Si=Si double bond may not be ruled out, a possible mechanism for the formation of 4 from 8 can involve the facile dissociation of 8 to 1′ followed by the isomerization of 1′ to 1 and the dimerization of 1 to afford 4.

Discussion

A heavy analogue of the smallest bridgehead alkene, Si4BBE 1 was successfully synthesized by coordinating to a Lewis base (1·DMAP) and their electronic structure was revealed. The elimination of DMAP from 1·DMAP afforded a mixture of dimers of Si4BBE and Si4BBY, compounds 4 and 8. The facile isomerization between compound 1 and its isomer Si4BBY 1′ was confirmed both experimentally and theoretically. Synthesis and reactions of Si4BBE 1 in this study can be regarded also as an example of contraction and expansion of unsaturated molecular silicon clusters37,38,39,40,41 (termed siliconoids by Scheschkewitz and colleagues37), which have received much attention as possible intermediates of vapour deposition of elemental silicon42,43. Transformation via elimination of silylene and/or skeletal isomerization may be a fascinating growth route of well-defined silicon clusters showing unique functions.

Methods

General methods

General procedure, materials, experimental details, X-ray analysis and theoretical study in this article are shown in Supplementary Methods. For NMR spectra, Oak Ridge Thermal Ellipsoid Plot (ORTEP) drawings and calculation results of the compounds in this article, see Supplementary Figs 1–31, Supplementary Figs 32–38, Supplementary Figs 39–50 and Supplementary Tables 1–13, respectively.

Thermolysis of tricyclo[2.1.0.01,3]pentasilane 2

To a Schlenk tube (30 ml) equipped with a magnetic stir bar, tricyclo[2.1.0.01,3]pentasilane 2 (27.5 mg, 0.0291, mmol) and benzene (3 ml) were added. The reaction mixture was heated at 40 °C for 10 h and then benzene was removed in vacuo. Recrystallization of the reaction mixture from hexane at −30 °C afforded pentacyclo[5.1.0.01,6.02,5.03,5]octasilane 4 as orange crystals (10.2 mg, 0.00893, mmol) in 61% yield. mp: 164 °C (decomposition); 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 0.42 (s, 18H, SiMe3), 0.44 (s, 18H, SiMe3), 0.485 (s, 18H, SiMe3), 0.491 (s, 18H, SiMe3), 1.51 (s, 18H, t-Bu), 1.54 (s, 18H, t-Bu), 1.92–2.20 (m, 8H, CH2); 13C NMR (100 MHz, C6D6): δ 4.39 (SiMe3), 5.16 (SiMe3), 5.23 (SiMe3), 5.58 (SiMe3), 14.2 (C), 17.4 (C), 25.0 (C), 27.4 (C), 32.5 (C(CH3)3), 34.7 (CH2), 35.0 (C(CH3)3), 36.8 (CH2); 29Si NMR (79 MHz, C6D6): δ −26.8 (Si), −18.4 (Si-t-Bu), −5.48 (Si-t-Bu), 3.98 (SiMe3), 4.22 (SiMe3), 4.33 (SiMe3), 4.50 (SiMe3), 24.6 (Si-RH2); HRMS (APCI) (m/z): calcd for C48H116Si16, 1,140.5380; found, 1,140.5392; ultraviolet–visible spectra (in hexane): λmax (ε) 370 nm (sh, 5,700), 329 nm (sh, 15,000), 268 nm (61,000); analysis (calcd, found for C48H116Si16): C (50.45, 50.59), H (10.23, 10.31).

Reaction of tricyclo[2.1.0.01,3]pentasilane 2 with DMAP

To a Schlenk tube (30 ml) equipped with a magnetic stir bar, tricyclo[2.1.0.0.1,3]pentasilane 2 (142.5 mg, 0.151 mmol), DMAP (140.8 mg, 1.152 mmol) and benzene (10 ml) were added. The reaction mixture was heated at 40 °C for 5 h and then benzene was removed in vacuo. Recrystallization of the reaction mixture from hexane at −35 °C afforded a mixture of DMAP adduct 1·DMAP and excess DMAP. Recrystallization of the resulting reaction mixture from benzene at room temperature afforded pure 1·DMAP as orange crystals (92.8 mg, 0.134 mmol) in 89% yield. The single crystals of 1·DMAP suitable for XRD study were obtained by recrystallization from benzene at room temperature. NMR spectra were measured in the presence of a slight excess of DMAP.

mp: 147 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6,): δ 0.03 (s, 9H, SiMe3), 0.38 (s, 9H, SiMe3), 0.61 (s, 9H, SiMe3), 0.83 (s, 9H, SiMe3), 1.48 (s, 9H, t-Bu), 1.62 (s, 9H, t-Bu), 1.88 (s, 6H, Me2N), 2.26–2.41 (m, CH2 (overlapped with the Me of free DMAP)), 2.24 (the Me of free DMAP), 5.52 (d, J=6.9 Hz, 2H, CH (pyridyl)), 6.11 (the CH of free DMAP), 7.70–8.60 (brs, 2H, CH (pyridyl)), 8.48 (the CH of free DMAP); 13C NMR (125 MHz, C6D6): δ 4.88 (SiMe3), 5.06 (SiMe3), 5.23 (SiMe3), 5.81 (SiMe3), 9.09 (C), 15.5 (C), 22.6 (C), 26.3 (C), 32.1 (C(CH3)), 34.8 (C(CH3)), 35.1 (CH2), 35.9 (CH2), 105.7 (CH), 155.7 (CH); 29Si NMR (99 MHz, C6D6): δ 1.16 (SiMe3), 2.62 (SiMe3), 4.23 (SiMe3), 4.41 (SiMe3), −79.8 (Si-t-Bu), −84.5 (Si-t-Bu), 13.3 (Si-RH2); 13C CP/MAS NMR (201 MHz): δ 4.42, 6.28, 9.11, 16.0, 24.3, 26.5, 32.6, 35.5, 41.4, 105.4, 107.2, 146.7, 150.4, 156.5; 29Si CP/MAS NMR (159 MHz): δ 1.41 (SiMe3), 2.87 (SiMe3), 3.36 (SiMe3), 5.07 (SiMe3), −79.3 (Si-t-Bu), 7.20 (Si-RH2), 78.2 (Si-t-Bu); HRMS (APCI) (m/z): ([M]+ was missing but [M+H3O+] was found.) calcd for C31H71N2OSi8, 711.3715; found, 711.3718; analysis (calcd, found for C31H68N2Si8): C (53.68, 53.35), H (9.88, 9.72), N (4.04, 4.17). In the 13C NMR spectrum in C6D6 solution, the signals due to the CH3 and aromatic carbons of coordinating DMAP were not observed. In the 29Si NMR spectrum, both in the solution and solid states the signal due to two-coordinate silicon nuclei (Si1) was not observed.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Iwamoto, T. et al. A heavy analogue of the smallest bridgehead alkene stabilized by a base. Nat. Commun. 5:5353 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6353 (2014).

Accession codes: The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 1007442 (1·DMAP), CCDC 1007443 (2·(benzene)0.5), CCDC 1007444 (2·(2,3-dimethy-1,3-butadiene)0.5), CCDC 1007445 (4·(benzene)), CCDC 1007446 (7), CCDC 1007447 (8) and CCDC 1007448 (9). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Bredt, J. Über sterische Hinderung in Brückenringen (Bredtsche Regel) und über die meso-trans-Stellung in kondensierten Ringsystemen des Hexamethylens. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 437, 1–13 (1924).

Köbrich, G. Bredt compound and the Bredt rule. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 12, 464–473 (1973).

Keese, R. Methods for the preparation of bridgehead olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1975, 528–538 (1975).

Shea, K. J. Recent development in the synthesis, structure and chemistry of bridgehead alkenes. Tetrahedron 36, 1683–1715 (1980).

Billups, W. E., Haley, M. M. & Lee, G.-A. Bicyclo[n.1.0]alkenes. Chem. Rev. 89, 1147–1159 (1989).

Dyer, S. F., Kammula, S. & Shevlin, P. B. Rearrangement of cyclobutenylidene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 8104–8106 (1977).

Killmar, H., Carrion, G., Dewar, M. J. S. & Bingham, R. C. Ground states of molecules. 58. The C4H4 potential surface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 5292–5303 (1981).

Maier, G. Tetrahedrane and cyclobutadiene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 27, 309–446 (1988).

Dinadayalane, T. C., Priyakumar, U. D. & Sastry, G. N. Exploration of C6H6 potential energy surface: A computational effort to unravel the relative stabilities and synthetic feasibility of new benzene isomers. J. Phys. Chem. A 108, 11433–11448 (2004).

Borst, M. L. G., Ehlers, A. W. & Lammertsma, K. G3(MP2) ring strain in bicyclic phosphorus heterocycles and their hydrocarbon analogues. J. Org. Chem. 70, 8110–8116 (2005).

Cremer, D., Kraka, E., Joo, H., Stearns, J. A. & Zwier, T. S. Exploration of the potential energy surface of C4H4 for rearrangement and decomposition reactions of vinylacetylene: A computational study. Part I. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 8, 5304 (2006).

Iwamoto, T., Tamura, M., Kabuto, C. & Kira, M. A stable bicyclic compound with two Si=Si double bonds. Science 290, 504–506 (2000).

Suzuki, K. et al. A planar rhombic charge-separated tetrasilacyclobutadiene. Science 331, 1306–1309 (2011).

Cowley, M. J., Huch, V., Rzepa, H. S. & Scheschkewitz, D. Equilibrium between a cyclotrisilene and an isolable base adduct of a disilenyl silylene. Nat. Chem. 5, 876–879 (2013).

Jana, A., Huch, V. & Scheschkewitz, D. NHC-stabilized silagermenylidene: a heavier analogue of vinylidene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 12179–12182 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. A stable silicon(0) compound with a Si=Si double bond. Science 321, 1069–1071 (2008).

Abersfelder, K., White, A. J. P., Rzepa, H. S. & Scheschkewitz, D. A tricyclic aromatic isomer of hexasilabenzene. Science 327, 564–566 (2010).

Tsurusaki, A., Iizuka, C., Otsuka, K. & Kyushin, S. Cyclopentasilane-fused hexasilabenzvalene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16340–16343 (2013).

Wiberg, N., Finger, C. M. M. & Polborn, K. Tetrakis(tri-tert-butylsilyl)-tetrahedro-tetrasilane (tBu3Si)4Si4: The first molecular silicon compound with a Si4 tetrahedron. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 32, 1054–1056 (1993).

Yates, B. F. & Schaefer, H. F. III Tetrasilacyclobutadiylidene: The lowest energy cyclic isomer of singet Si4H4? Chem. Phys. Lett. 155, 563–571 (1989).

Haunschild, R. & Frenking, G. Tetrahedranes. A theoretical study of singlet E4H4molecules (E=C–Pb and B–Tl). Mol. Phys. 107, 911–922 (2009).

Sekiguchi, A., Matsuno, T. & Ichinohe, M. The homocyclotrisilenylium ion: a free silyl cation in the condensed phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 11250–11251 (2000).

Iwamoto, T. et al. Anthryl-substituted trialkyldisilene showing distinct intramolecular charge-transfer transition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 3156–3157 (2009).

Scheschkewitz, D. A molecular silicon cluster with a “naked” vertex atom. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 2954–2956 (2005).

Kira, M., Ishida, S., Iwamoto, T. & Kabuto, C. The first isolable dialkylsilylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 9722–9723 (1999).

Leszczynska, K. et al. Reversible base coordination to a disilene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 6785–6788 (2012).

Kaftory, M., Kapon, M. & Botoshansky, M. inThe Chemistry of Organic Silicon Compounds Vol. 2, eds Rappoport Z., Apeloig Y. Ch. 5181–266John Wiley & Sons (1998).

Jones, R., Williams, D. J., Kabe, Y. & Masamune, S. The tetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]butane system: structure of 1,3-di-tert-butyl-2,2,4,4-tetrakis(2,6-diethylphenyl)tetrasilabicyclo[1.1.0]butane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 25, 173–174 (1986).

Ueba-Ohshima, K., Iwamoto, T. & Kira, M. Synthesis, structure, and facile ring flipping of a bicyclo[1.1.0]tetrasilane. Organometallics 27, 320–323 (2008).

Wiberg, N., Schuster, H., Simon, A. & Peters, K. Hexa-tert-butyldisilane - the molecule with the longest Si-Si bond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 25, 79–80 (1986).

Okazaki, R. & West, R. Chemistry of stable disilenes. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 39, 231–273 (1996).

Kira, M. & Iwamoto, T. Progress in the chemistry of stable disilenes. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 54, 73–148 (2006).

Ohms, U. & Guth, H. Die Kristall- und Molekülstruktur von 4-Dimethylaminopyridin C7H10N2 . Z. Kristal 166, 213–218 (1984).

Inoue, S., Ichinohe, M., Yamaguchi, T. & Sekiguchi, A. A free silylium ion: a cyclotetrasilenylium Ion with allylic character. Organometallics 27, 6056–6058 (2008).

Cowley, M. J., Huch, V. & Scheschkewitz, D. Donor-acceptor adducts of a 1,3-disila-2-oxyallyl zwitterion. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 9221–9224 (2014).

Jutzi, P. et al. Reversible transformation of a stable monomeric silicon(II) compound into a stable disilene by phase transfer: experimental and theoretical studies of the system {[(Me3Si)2N](Me5C5)Si} n with n=1,2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 12137–12143 (2009).

Abersfelder, K. et al. Contraction and expansion of the silicon scaffold of stable Si6R6 isomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16008–16016 (2012).

Fischer, G. et al. Si8(SitBu3)6: a hitherto unknown cluster structure in silicon chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 7884–7887 (2005).

Nied, D., Köppe, R., Klooper, W., Schnöckel, H. & Breher, F. Synthesis of a pentasilapropellane. Exploring the nature of a stretched silicon-silicon bond in a nonclassical molecule. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10264–10265 (2010).

Abersfelder, K., White, A. J. P., Berger, R. J., Rzepa, H. S. & Scheschkewitz, D. A stable derivative of the global minimum on the Si6H6 potential energy surface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7936–7939 (2011).

Ishida, S., Otsuka, K., Toma, Y. & Kyushin, S. An organosilicon cluster with an octasilacuneane core: a missing silicon cage motif. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 2507–2510 (2013).

Lyon, J. T. et al. Structure of silicon cluster cations in the gas phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 1115–1121 (2009).

Haertelt, M. et al. Gas-phase structures of neutral silicon clusters. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 064301 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant number 25248010 (T.I.), 25708004 and 25620020 (S.I.), and MEXT KAKENHI grant number 24109004 (T.I.) (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas ‘Stimuli-responsive Chemical Species’).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.I., N.A. and S.I. designed the experiments. N.A. synthesized and characterized all the compounds. N.A. and S.I. conducted XRD analysis. T.I. performed theoretical calculations. T.I., N.A. and S.I. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-50, Supplementary Tables 1-13, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 9555 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iwamoto, T., Akasaka, N. & Ishida, S. A heavy analogue of the smallest bridgehead alkene stabilized by a base. Nat Commun 5, 5353 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6353

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6353

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.