Abstract

One of the most desirable goals of graphene research is to produce ordered two-dimensional (2D) chemical derivatives of suitable quality for monolayer device fabrication. Here we reveal, by focal series exit wave reconstruction (EWR), that C2F chair is a stable graphene derivative and demonstrates pristine long-range order limited only by the size of a functionalized domain. Focal series of images of graphene and C2F chair formed by reaction with XeF2 were obtained at 80 kV in an aberration-corrected transmission electron microscope. EWR images reveal that single carbon atoms and carbon–fluorine pairs in C2F chair alternate strictly over domain sizes of at least 150 nm2 with electron diffraction indicating ordered domains ≥0.16 μm2. Our results also indicate that, within an ordered domain, functionalization occurs on one side only as theory predicts. In addition, we show that electron diffraction provides a quick and easy method for distinguishing between graphene, C2F chair and fully fluorinated stoichiometric CF 2D phases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The extraordinary structural and transport properties of graphene1 have given rise to an intense interest in its morphological and chemical modification, resulting in an extensive range of derivative materials. This has been driven by the consideration that graphene itself must be modified to achieve a usable band gap and other desirable low-dimensional properties. One approach is the nano-engineering of graphene to form nano-ribbons so that charge carriers are confined to a quantum wire2,3. A more scalable approach is the formation of chemical derivatives such as graphene oxide (GO)4,5, hydrogenated graphane (CH)6 or fluorinated graphene (CxF, x≤4)7,8,9. GO consists of graphene sheets decorated with epoxy, hydroxyl and carboxyl groups4, whereas graphane is hydrogenated graphene6. For some derivatives, structural order on length scales further than a few C–C bond distances cannot be demonstrated and for GO, even the local structure remains a matter for significant debate4. For graphane, no long-range order is observed owing to the absence of uniformity in the corrugations of the benzene ring7, a problem compounded by the low stability of this structure at moderate temperatures6.

Stoichiometric fluorographene8, a graphenic monolayer with each fluorine atom bonded to a carbon atom in a distorted sp3 sheet, would appear to be the most likely candidate for a usable graphene derivative. This material is a thermally and chemically stable insulator with similar mechanical strength to graphene, offering a range of possible applications8,9,10,11,12,13. However the reported two-dimensional (2D) lattice constant for CF is ~0.248 nm, which is apparently expanded only 1% relative to graphene, significantly lower than the 2.8% expanded lattice constant for monolayer CF predicted by the density functional theory (DFT) and notably also less than the 2.8–4.5% expanded lattice constant variously reported for graphite fluoride8,10,14,15. The observed lower lattice parameter reported for CF indicates that this phase may undergo significant lattice corrugation that will impair its utility in any application requiring a ‘flat’ 2D morphology. Here we show, using electron diffraction (ED) and aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopy (AC-TEM) in tandem with exit wave reconstruction (EWR)16,17,18,19, that the DFT-predicted phase C2F chair10 is both stable and demonstrates a far higher degree of pristine long-range structural and morphological order than CF or any other chemical derivative of graphene. Our observations also support theoretical predictions10 that, due to energetic considerations, ordered domains of C2F chair are functionalized exclusively on one side, a result with profound implications for the preparation of 2D devices and, furthermore, the formation of secondary chemical derivatives such as those formed by alkylation, hydroxylation and amino-functionalization20. In addition, new carefully calibrated ED studies performed on a freshly fluorinated graphene monolayer sample (i.e. CxF (x=1,2)) provide a domain-by-domain 2D phase analysis that not only supports the conclusion of our EWR studies, but also reveals that some domains of fully fluorinated graphene may possibly be uncorrugated.

AC-TEM can provide information about atomic arrangements within materials at low accelerating voltages, reducing specimen damage, although images are often noisy and difficult to interpret. High-angle annular dark field imaging performed in scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) produces higher definition images, but may degrade thin monolayers due to the high electron flux of the highly focused electron beam. EWR16,17,18,19 can recover more information from AC-TEM by combining data from a focal series of low beam density images, providing light element sensitivity and even 3D information21.

We present here comparative EWR phase images calculated from focal series obtained from both pristine graphene and also partially fluorinated 2D monolayer C2F chair samples under nearly identical imaging conditions. This imaging technique permits direct imaging of individual C atoms and alternating C–F atom pairs at atomic resolution, and the obtained images also indicate pristine long-range order in this structure. The preservation of the microstructure of C2F during extended focal series acquisition is furthermore an important indicator of its comparative stability for unperforated C2F chair monolayers. However, we also reveal how prolonged electron beam irradiation of this material to form perforated monolayers leads to sequential sputtering of F atoms and C atoms from the terminal edge of a hole leading to a modified decomposition sequence relative to similar sputtering reported for graphene.

Results

Preparation and general characterization of monolayer CxF

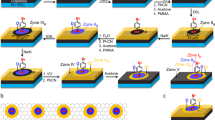

Chemical vapour deposition (CVD)-grown graphene (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. 1a) was suspended on TEM ‘Quantifoil’ specimen grids by applying previously published protocols for the synthesis, transfer and cleaning of this material22,23. Monolayer CxF (with possible microstructures indicated in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1b–e (ref. 10)) was then produced by partially fluorinating additional suspended graphene samples, using the previously reported XeF2 direct fluorination method8,23 (Methods section). While this technique can also be used to produce stoichiometric CF (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. 1d), careful regulation of the extent of fluorination enables partially fluorinated samples to be prepared by adjusting the applied temperature between the range 70 and 200 °C (ref. 8). We performed carefully calibrated ED studies on an initial sample (Fig. 1b,c) and subsequently a freshly prepared fluorinated graphene sample (Supplementary Fig. 2) to test the distribution of 2D phases in both preparations as predicted by DFT by Şahin10 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, ED simulations in Fig. 1d–f and Supplementary Fig. 1f), as EELS studies performed on the initial sample (Supplementary Fig. 3a) indicated some possible sample deterioration. In the new study, energy dispersive X-ray microanalysis was performed simultaneously with the ED study (Supplementary Fig. 3b) and clearly revealed the presence of fluorine in specimens with an enlarged lattice parameter, although some contaminaiton was also indicated. Additional Raman studies (Supplementary Fig. 4) suggest that the extent of fluorination is quite variable across this sample with an uneven distribution of sp3 versus sp2 functionalization, although the poor spatial resolution of this method (typically 1 μm2) is unlikely to give a clear picture of the ordering within CxF on a domain-by-domain basis.

(a) (Left to right) perspective models of graphene, stoichiometric fluorographene, C2F chair and C2F boat. (b) ED patterns obtained from graphene (subscripted GR) with overlaid scaled ED pattern obtained from monolayer C2F (subscripted C2F) with hkil  010-type and

010-type and  -type reflections indicated for both phases (scale bar, 5 nm−1). (c) Intensity line profiles obtained through

-type reflections indicated for both phases (scale bar, 5 nm−1). (c) Intensity line profiles obtained through  010 and

010 and  0-type reflections for graphene and monolayer C2F. (d,e) Structure model (left), experimentally determined unit cells produced from calibrated ED data in b and c and ED patterns (right) for graphene and C2F chair (scale bar, 5 nm−1). The estimated precision of the unit cells is at least ±0.6%. (f) DFT-determined structure for C2F boat9 together with simulated ED pattern (hkl indices, scale bar, 5 nm−1).

0-type reflections for graphene and monolayer C2F. (d,e) Structure model (left), experimentally determined unit cells produced from calibrated ED data in b and c and ED patterns (right) for graphene and C2F chair (scale bar, 5 nm−1). The estimated precision of the unit cells is at least ±0.6%. (f) DFT-determined structure for C2F boat9 together with simulated ED pattern (hkl indices, scale bar, 5 nm−1).

ED studies of graphene and CxF

ED was carried out on graphene and the initial monolayer CxF sample using a diffraction aperture of ~0.16 μm2 and equivalent exposure conditions for both materials. Overlaid ED patterns for pristine graphene (Fig. 1b, white spots) and the CxF phase (Fig. 1b, red spots) both show sixfold symmetry with the sharp intensities of the latter pattern indicating a high degree of order24. In addition, the ratios of  to

to  -type reflections are consistent with those obtained for graphenic monolayers24, whereas the measured unit cell revealed a 2.4% expanded lattice parameter (that is, a1,a2=0.251±0.008 nm), larger than the 0.248-nm parameter reported for ‘corrugated’ CF8, although less than the value predicted for ‘uncorrugated’ CF (Supplementary Table 1)10. The indicated unit cell is also in good agreement with the unit cell predicted by DFT for C2F ‘chair’ functionalized on one side only (that is, a1,a2=0.252 nm)10. The relative intensities of

-type reflections are consistent with those obtained for graphenic monolayers24, whereas the measured unit cell revealed a 2.4% expanded lattice parameter (that is, a1,a2=0.251±0.008 nm), larger than the 0.248-nm parameter reported for ‘corrugated’ CF8, although less than the value predicted for ‘uncorrugated’ CF (Supplementary Table 1)10. The indicated unit cell is also in good agreement with the unit cell predicted by DFT for C2F ‘chair’ functionalized on one side only (that is, a1,a2=0.252 nm)10. The relative intensities of  0-type reflections for graphene and the C2F phase scale in a manner consistent with adding an additional F atom per C2F unit cell relative to graphene (Fig. 1c)25. No domains with ED corresponding to the tetragonal 'boat' form of C2F, also predicted by DFT (with lattice parameters a1=0.254 nm; b1=0.436 nm10), were observed that can readily be distinguished from the chair form of C2F by ED simulations generated from both the DFT-predicted forms (that is, cf. Fig. 1b,e,f). ED patterns obtained from about 20 regions of the initial CxF sample indicated that ~70% of the observed domains had a similar microstructure, with EWR studies indicating that many of these exhibited short- to long-range order. Stoichiometric CF has so far not been identified in this initial CxF sample.

0-type reflections for graphene and the C2F phase scale in a manner consistent with adding an additional F atom per C2F unit cell relative to graphene (Fig. 1c)25. No domains with ED corresponding to the tetragonal 'boat' form of C2F, also predicted by DFT (with lattice parameters a1=0.254 nm; b1=0.436 nm10), were observed that can readily be distinguished from the chair form of C2F by ED simulations generated from both the DFT-predicted forms (that is, cf. Fig. 1b,e,f). ED patterns obtained from about 20 regions of the initial CxF sample indicated that ~70% of the observed domains had a similar microstructure, with EWR studies indicating that many of these exhibited short- to long-range order. Stoichiometric CF has so far not been identified in this initial CxF sample.

Following careful calibration of the camera length of our electron microscope with a polycrystalline gold sample (Supplementary Fig. 2a), we were able to distingush between different domains (or 2D phases) of graphene, C2F chair and could even identify stoichiometric CF (with the enlarged 0.255-nm lattice parameter as predicted by Şahin10) for 18 different fragments of a freshly prepared CxF sample with a high degree of confidence. This sample was found to contain domains of unfluorinated graphene and 2D phases with a lattice parameter conforming to C2F chair, as described above. The distribution of 2D phases in this sample was found to be 7:9:2 for graphene, C2F chair and stoichiometric CF, respectively (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). These results suggest that one-sided fluorination is rapid and completely ‘coats’ one side of graphene with fluorine before the opposing side is fluorinated, a process which may be initiated either catalytically or by defects.

Imaging of graphene and C2F chair by EWR

EWR was then employed on domains of graphene and C2F chair exhibiting comparable ED behaviour to Fig. 1d,e and also in terms of the enlarged ~0.252-nm lattice parameter. For both structures, focal series consisting of 34 images were obtained at 80 kV in an AC-TEM (Methods section, Supplementary Figs 5 and 6). The image in Fig. 2a shows the restored phase for a ~100-nm2 graphene domain obtained with ~0.09 nm resolution, and details obtained from the EWR and false-colour images (Fig. 2b,c) produced by thresholding the phase to reveal the positions of the C atoms (highlighted in blue) comprising the graphene lattice. Line profiles obtained along C–C dumbells (see also Fig. 3a,c) reveal bonds of ~0.142±0.008 nm, consistent with monolayer graphene. In Fig. 2d–f, an EWR phase image, detail and false-colour image obtained from a ~144-nm2 domain of C2F is then shown. The important outcome of the EWR images is the heightening of the phase shift due to –CF< pairs relative to the >C– atoms, as suggested by the inset model in Fig. 2e. As above, the false-colour map in Fig. 2f indicates the positions of the single C atom columns in blue while the >CF– pairs indicated by green peaks occur on strictly alternating C positions. In Fig. 2g–i, we show low magnification, detail and thresholded simulated EWR images of domains of the fluorographene equivalent in size to the experimental images reproduced in Fig. 2d–f that are in good agreement with these images.

(a) Experimental (EXP) restored phase obtained from a ~64-nm2 domain of graphene. (b) Higher magnification view of the restored phase produced from the highlighted domain in a graphene ‘ball-and-stick’ model overlaid. (c) Thresholding the detail in b produces a false-colour plot, in which the blue spots corresponds to the phase shift produced by individual C atoms in graphene. (d–f) Same as a–c, but for C2F chair with F atoms separately highlighted in green. (g–i) Simulated phase images for C2F chair. The intensity distribution of the simulation provides an excellent match with the experimental phase image in f. Scale bar, 3 nm (a,d,g); scale bar, 0.5 nm (b,c,e,f,h,i).

(a,b) Graphene and C2F models with C–C and C–CF dumbbells highlighted. (c,d) Equivalent domains of experimental (EXP) and simulated (SIM) phase images for monolayer graphene and C2F chair, respectively. (e,f) Colour-coded line profiles obtained from the indicated regions in c and d for the EXP and SIM phase images for graphene and C2F chair. The line profiles obtained from the SIM images are artificially downshifted by ~0.02 rad for clarity. The peaks in e correspond to three graphene dumbbells, whereas the three saw-tooths in f correspond to >C– atoms (low peaks) and –CF< pairs (tall peaks) in a strict >C–CF< sequence. (g) Overlaid full plots of the experimental (EXP) and simulated (SIM) phase contrast for pristine graphene, respectively. (h) Overlaid full plots of the experimental (EXP) and simulated (SIM) phase contrast for C2F chair, respectively. Note that the net phase shift for single C atoms in grapheme, (that is, |φ|) ~0.5 rad, differs from the net phase shift for single C atoms in C2F chair (~0.08 rad) due to the convolution of this with the net phase shift for –CF< pairs (that is, ~0.1 rad). See also Supplementary Fig. 8a,b.

In Fig. 3a–f, a more detailed interpretation of enlarged 8 × 17 nm domains of both experimental and simulated phase images is shown (Fig. 2d,g). The two models in Fig. 3a,b correspond to domains of graphene and C2F chair as imaged in Fig. 3c,d. Shown side-by-side with the experimental images are simulations computed from the models in Fig. 3a,b. Figure 3e,f shows overlaid line profiles corresponding to the diffuse lines in Fig. 3c,d. In Fig. 3e, the phase image and simulations produce clearly defined dumbbells for monolayer graphene with peaks separated by 0.142 nm, equivalent to the graphenic >C–C< separations. Experimental and simulated line profiles for C2F in Fig. 3f for three >C–CF< dumbbells are present with saw-tooth profiles, with the low peaks corresponding to single >C– atoms and the taller peaks to >C–F pairs. These are separated by ~0.146 nm, equivalent to the tetrahedrally distorted 0.148 nm >C–CF< distance (predicted by DFT10) imaged in a ‘plan view’ projection (cf. C2F chair in Fig. 1a)10. Computing the experimental >C–CF< distance from the reported buckling (δ) of 0.029 nm for C2F chair from the average experimental ‘plan view’ distance gives ~0.149 nm, consistent with the reported DFT value for the >C–CF< distance within experimental error. In addition, the relative magnitude of the experimentally determined and simulated atom column phase shifts for single –C< columns and >C–F pairs give a clear distinction between carbonaceous graphene and C2F chair, and are in excellent agreement with simulated phase shifts computed for the aberration values determined for our instrument (that is, Fig. 3g,h, see also Methods section). The relative phase shifts and spatial distributions of these features also readily allow us to distinguish between this microstructure and that for the boat form of C2F, as well as that for stoichiometric fluorographene, by performing comparisons with simulations obtained for all four structural forms taking into account net phase shifts for single C columns versus corresponding shifts for >C–F pairs (see Supplementary Figs 7 and 8).

The line profiles in Fig. 3f reveal that the functionalization of C2F chair exhibits outstanding short-range order. Wider field-of-view images in Fig. 2d, Fig. 4a,b and also Fig. 5a,b give indications of how this order is retained for larger-sized domains. In the false-colour surface profile image in Fig. 4c (generated from Fig. 4b), the peaks correspond to the measured phase shift in C and CF atom columns for a ~64-nm2 area of C2F chair. A triangulation of three 8-pixel line profiles (I, II and III, Fig. 4b) through a total of 51 >CF–C< or >C–CF< dumbbells is reproduced in Fig. 4d. The taller –CF< peaks predominate in the profile image, and over the entire domain the microstructure maintains pristine order. A comparison of this region with the wider field-of-view image (Fig. 4a) indicates that the ordering extends well beyond the range of this image possibly to regions equivalent in size to the ED aperture (~0.16 μm2). Notably, there is little rippling in the domains inFigs 2 and, 4 although small ripples are present in the wider field-of-view image, indicating that the significant corrugation reported for stoichiometric CF8 is absent. A larger ~150-nm2-ordered domain image (Supplementary Fig. 9) also presents with little rippling and, most significantly, with no evidence of short- or long-range disorder or strain effects associated with local disruption of the C2F chair 2D lattice.

(a) EWR image of a 250-nm2 sheet of highly ordered sheet C2F with an unrippled 64-nm2 domain highlighted. Outside this domain, ripples are visible (scale bar, 4 nm). (b) Enlargement of the 64-nm2 domain exhibiting a high degree of order (scale bar, 2 nm). (c) Surface plot from b in which the orange–yellow apexes correspond to ordered –CF< units within an extended C2F domain with less visible peaks corresponding to single >C– atoms. (d) Three line profiles (I–III) obtained through either >CF–C< or >C–CF< dumbbells (units of Φ are rad).

(a) EWR of a highly ordered domain of C2F chair during hole formation. On the left, the C2F chair microstructure is clearly resolved but is more diffuse towards the hole edge (scale bar, 2 nm). (b) Detail from a (that is, region I) revealing the microstructure at the hole edge (scale bar, 1 nm). At the edge, the enhanced contrast of the arrowed >C–F positions is reduced due to the progressive elimination of F. (c) Enlarged lower region from a showing diffuse contrast from expanded C-rings at the periphery of the hole (scale bar, 0.5 nm). The arrowed edge features correspond to the dominant microstructure present during focal series acquisition, however, this blurry region is difficult to interpret. (d) Time-resolved AC-TEM images obtained close to Scherzer imaging conditions. Top image shows a ‘plan view’ of the entire hole after 5 s exposure. Middle panel shows a 1-s exposure image with seven to eight expanded C-rings at the edge. At 3 s elapsed time, five of these rings still remain although two further rings at the extreme left have newly reformed. After 5 s total illumination, the entire row is removed leaving an exposed surface layer of C2F hexagons (scale bar, 2 nm). (e) Detail from b (left) and structure model (right) indicating the C2F chair microstructure during fluorine removal at the edges (scale bar, 0.4 nm). (f) Sequence of unfiltered enlargements from the three bottom insets in d (I at 1 s; II at 3 s and III at 5 s. Scale bar, 0.5 nm). The C-hexagon indicated by the small black arrow indicates one static point in the image sequence. (g) Three models suggested by the three enlargements I–III in f with the static point indicated. The dominant edge microstructure in I and II are seven to eight reconstructed zig-zag (or ‘reczag’) units formed from five- and seven-membered C-rings, respectively, known to form for carbonaceous graphene although these are probably depleted in f. These units are both mobile and unstable and first rearrange and then are eliminated at III. A possible Klein edge is indicated at K.

Prolonged in situ electron beam irradiation studies of CFx

We have also investigated the stability of the C2F chair microstructure following prolonged exposure to an electron beam at 80 kV (Fig. 5a–g). During sample irradiation, a region of monolayer C2F chair material was exposed to an electron beam density of ca. 106 e−nm−2 for 20 min after which both focal series and ‘single shot’ AC-TEM images (Fig. 5d) were recorded from regions of hole formation (see Methods section). In Fig. 5a–c, an EWR phase image and details obtained from a typical hole are shown. A few C–C bond distances from the edge of the hole, the microstructure of the C2F chair monolayer is perfectly retained while at the periphery the contrast is somewhat reduced, possibly indicating preferential removal of single fluorine atoms from the edges (which can be induced more systematically26). In the edge enlargement in Fig. 5c, we see that there are some residual carbon fragments (arrowed), but both focal series images and image series obtained at optimum defocus (Fig. 5d) indicate dynamical rearrangement of the microstructure at the edges (Fig. 5e). The first 1–3-s exposures following prolonged illumination reveal the presence of reconstructed zig-zag (‘reczag’) features consisting of five- and seven-membered ring pairs, which have been reported for holes formed from pristine graphene, although migration of C–C atoms pairs along graphene edges is more common27,28. We also note that these edge features are mobile, and a partial shunt of all the reczag units (resulting in the formation of a single Klein edge feature27) along the edge is observed (that is, Fig. 5f), as suggested by the models in Fig. 5g just prior to elimination of the whole row from the edge of the hole after 5 s. Taken together, these results underscore the comparative stability of the C2F chair monolayers that only degrade following prolonged electron beam exposure at 80 kV. Elimination of F from the C2F chair structure at the hole edges results in more graphene-like behaviour and similar edge reconstruction behaviour to that previous reported for graphene in particular.

Discussion

ED and EWR both reveal that C2F chair is an ordered 2D monolayer material, but how stable is this structure and how reliable is our assertion of one-side functionalization? The robustness of the C2F chair 2D phase in the electron beam during focal series acquisition is a strong indicator of its stability, especially in comparison with other part-functionalized graphene materials. Erni et al.29 demonstrated that ad-atoms and ad-molecules chemically attached to graphene can be imaged by EWR in an AC-TEM, using focal series of up to 11 images with comparable exposure conditions to those employed here (see Methods section). We were able to take a series of up to 34 images for EWR images for domain sizes >64 nm2 (that is, Fig. 4a–c) with no evidence of significant rearrangement of the local microstructure, although eventually the C2F chair monolayers do degrade but only following prolonged beam exposure at 80 kV for 20 min or more. This latter behaviour is wholly consistent with similar observations reported for both pristine and other chemically modified graphenic monolayers27,28.

The assertion that fluorine functionalization of C2F chair occurs on one side is justified by the bond lengths derived from ED patterns and reported theory10, although both sides of the graphene were simultaneously exposed to XeF2 (ref. 8). In addition, our ED study on a freshly fluorinated graphene sample reveals that unfluorinated graphene domains, partially fluorinated C2F chair and fully fluorinated graphene (designated Gr, Ch.-C2F Stoich-CF, in the accompanying schematic in Supplementary Table 2). In their DFT study, Şahin et al.10 indicate that C2F chair functionalized on one side has the lowest formation energy relative to graphene (that is, 0.09 eV) in comparison with 1.44 eV for C4F, 0.91 eV for C2F boat and 2.04 eV for CF9. While C2F boat may be inherently more stable, formation of this structure requires fluorination on adjacent C atoms, whereas C2F chair requires fluorination on alternating C atoms, a less sterically hindered process (cf. C2F chair and boat models, Fig. 1a). In addition, once fluorination nucleates on one side, it may progress energetically downhill until the domain functionalized on one side before obverse fluorination occurs. If true, our work provides support for the proposed one-sided stepwise fluorination sequence suggested for stoichiometric CF10, and the observation of well-defined graphene, C2F chair and stoichiometrically fluorinated domains of CF provide strong support for this (i.e. Supplementary Table 2). We also note that a triangular lattice with F sitting on top and below would be a frustrated system, a classical example of which is spin ice30 and, additionally, local deviation from one-sided functionalization would result in readily observable topological distortions in the (C2F)3 chair rings and longer-range strain effects31. In none of the experimental images do we see such distortions and the (C2F)3 chair rings all retain an undistorted hexagonal shape. In addition, the lack of disorder in the ED patterns (Fig. 1b) is further evidence for the lack of distortion or other forms of disorder.

We note that other modes of fluorination have been reported. Robinson et al.32 reported one-sided fluorination at 1,4 positions on the graphene rings to form C4F, when graphene was initially exposed to XeF2 on one side. This material was then converted to stoichiometric CF following subsequent fluorination of the interim product on both sides. Lee et al.33 presented calculations in support of this, although these do not address out-of-plane distortions that may be key in terms of establishing the fluorination mechanism. We unequivocally observe only 1,3,5 fluorinated graphene C2F chair domains in our partially fluorinated samples, and we find no evidence for a C4F-ordered superstructure (Supplementary Fig. 1e,d. See also ref. 10) in our partially fluorinated material. If both cases are true, this suggests that different fluorination mechanisms may be achieved by subtle alteration of the reaction conditions, as indicated by Şahin et al10. Additional microstructural studies may help to confirm the alternative fluorination mechanisms suggested by Robinson et al.32

In conclusion, we have for the first time characterized both the structure and stoichiometry of an alternating fluorinated graphene material with atomic resolution using EWR. C2F chair is a highly ordered material that demonstrates selective alternating fluorination on one side for domains >150 nm2 in accord with previous theoretical work10. Our results indicate that preferential functionalization of graphene by fluorine on one side appears to be energetically favoured even when graphene is exposed on both sides to XeF2 (refs 8, 32). The observed single-sided domains are likely to self-organise due to the finite mobility of F atoms along graphene10, resulting in clean patches being randomly fluorinated on the top or bottom sides. The strongly electronegative character of the >C–CF< functionals combined with the highly anisotropic nature of mono-sided functionalization indicate a significant potential for creating ordered secondary derivatives from C2F (refs 20, 34). Furthermore, C2F chair presents with an undistorted 2D morphology in contrast with stoichiometric, but corrugated, CF with the consequence that the former is a potentially much more tractable material for 2D device fabrication8.

Methods

Preparation of graphene and C2F films for AC-TEM

CVD-grown graphene 2D crystals used for the comparative imaging study of this material were first synthesized, transferred onto Quantifoil AC-TEM grids and then cleaned according to standard published protocols22,23. A second Quantifoil-suspended CVD graphene sample was also prepared for fluorination using the same method. Fluorination was performed on this second sample by direct fluorination with XeF2 gas in a Teflon container at 70 °C (ref. 8). Raman spectroscopy was performed on as-prepared fluorinated CVD graphene membranes prepared on TEM grids before performing the TEM experiments. These studies were performed using a Renishaw spectrometer equipped with a 514-nm laser and using a ~1-μm diameter spot.

EWR and simulation

A JEM-ARM 200F microscope operating at 80 kV equipped with a CEOS aberration corrector and a Gatan SC1000 ORIUS camera with a 4008 × 2672 pixel charge-coupled device (CCD) was used for TEM investigations. EWR was carried out using the 34 images through focal series with focal steps of ~1.5 nm and a sampling rate of 0.00811, nm per pixel, satisfying the Nyquist criterion. Electron beam densities were adjusted to be similar to those reported in ref. 26 (that is, 106 e−nm−2). Typical values for the residual aberrations of the JEOL ARM 200F were recorded as follows Defocus: (C1)=−318±2 nm; twofold astigmatism: (A1)=6±2 nm, threefold astigmatism: (A2)=44±10 nm, coma: (B2)=22±10 nm, third-order spherical aberration: (C3)=1.22±08 μm, fourfold astigmatism: (A3)=390±100 nm, star aberration: (S3)=1.2±0.2 μm, fivefold astigmatism: (A4) 140±10 μm. It must be noted that these values are acquired at a magnification of × 500,000 and drift in real time, and may undergo further drift when the lattice images of graphene and C2F chair were obtained. These considerations notwithstanding, typical resolutions were obtained from FWHM measurements of individual atom columns from EWR reconstruction reveal spatial frequencies of ~0.11–0.12 nm, with fast Fourier transforms (FFTs) obtained from individual lattice images indicating a spatial resolution of ~0.094 nm.

The FTSR package by HREM Research was used to perform EWR19. AC-TEM simulations of graphene and C2F were calculated using a finite-difference multi-slice simulation routine. The graphene and C2F models were constructed in Mathematica 8.0 (Wolfram Research Inc.) with bond lengths and angles adopted from DFT models10. Simulated EWR images were calculated using parameters matching the experimentally determined C3 for our instrument using a fast multi-slice algorithm as described in ‘Advanced Computing in Electron Microscopy’ 2nd edn. by E. J. Kirkland, Springer, 2010. To investigate the stability of the structure under the electron beam, a single monolayer of C2F chair was exposed to an electron beam for ~20 min under the same illumination conditions employed for focal series acquisition, which produced a hole in the C2F chair sheet. After hole formation, a focal series of 30 images with a focal step of 1.5 nm, sampling rate of 0.00782, nm per pixel and exposure time of 1 s per image was acquired and used to reconstruct the exit wave from the drilled hole.

EELS studies were also performed on a freshly prepared and partially fluorinated graphene samples in a VG-HB501 STEM (SuperSTEM) situated at Daresbury Laboratories, UK, equipped with a cold field-emission filament operating at 100 kV±0.3 eV, a Gatan Enfina electron energy loss spectrometer with a total spectral resolution of 0.5 eV. Energy dispersive X-ray studies were performed on monolayer fluorinated graphene samples in the ARM 200F AC-TEM using a ~3-nm probe and an Oxford Instruments SDD X-ray microanalysis detector. ED patterns were obtained in the same instruments and on the same samples using a ~0.16-μm2-selected area diffraction aperture using a 20-cm camera length and using 400852672 pixel CCD. The latter was calibrated with a polycrystalline Au sample (a typical pattern is recorded in Supplementary Fig. 2a) similar to the method described in ref. 35. The precision of the lattice parameter measurement is at least 0.6% (that is, limited by the Au calibration), although individual reflections on ED patterns recorded from monolayer graphene and fluorographene samples can be measured with a precision of ~0.15%.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Kashtiban, R. J. et al. Atomically resolved imaging of highly ordered alternating fluorinated graphene. Nat. Commun. 5:4902 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5902 (2014).

Change history

12 November 2014

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191 (2007).

Han, M. Y., Özyilmaz, B., Zhang, Y. & Kim, P. Energy band-gap engineering of graphene nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 206805 (2007).

Li, X., Wang, X., Zhang, L., Lee, S. & Dai, H. Chemically derived, ultrasmooth graphene nanoribbon semiconductors. Science 319, 1229–1232 (2008).

Dreyer, D. R., Park, S., Bielawski, C. W. & Ruoff, R. S. The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 228–240 (2010).

Hossain, M. d. Z. et al. Chemically homogeneous and thermally reversible oxidation of epitaxial graphene. Nat. Chem. 4, 305–309 (2012).

Elias, D. C. et al. Control of graphene's properties by reversible hydrogenation: evidence for graphane. Science 323, 610–613 (2009).

Bangert, U., Pan, C. T., Nair, R. R. & Gass, M. H. Structure of hydrogen-dosed graphene deduced from low electron energy loss characteristics and density functional calculations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 283118 (2010).

Nair, R. R. et al. Fluorographene: a two-dimensional couterpart of Teflon. Small 6, 2877–2884 (2010).

Sato, Y., Itoh, K., Fukunaga, T. & Ito, Y. Short-range structure of poly(dicarbon monofluoride) (C2F)n and poly(carbon monofluoride) (CF)n . Carbon. N.Y. 42, 2897–2903 (2004).

Şahin, H., Topsaka, M. & Ciraci, S. Structures of fluorinated graphene and their signatures. Phys. Rev. B 83, 115432 (2011).

Lee, W. H. et al. Area fluorination of graphene with fluoropolymer and laser irradiation. Nano Lett. 12, 2374–2378 (2012).

Cheng, S.-H. et al. Reversible fluorination of graphene: evidence of a two-dimensional wide bandgap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. B 81, 205435 (2010).

Gong, P. W. et al. One-pot sonochemical preparation of fluorographene and selective tuning of its fluorine coverage. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 16950–16956 (2012).

Kita, Y., Watanabe, N. & Fujii, Y. Chemical composition and crystal structure of graphite fluoride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 3832–3841 (1979).

Touhara, H., Kadono, K., Fujii, Y. & Watanabe, Y. N. On the structure of graphite fluoride. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 544, 7 (1987).

Saxton, W. O. inComputer Processing of Electron Microscope Images (ed. Hawkes P. W. Springer (1980).

Coene, W. M. J., Thust, A., Op de Beeck, M. & Van Dyck, D. Maximum-likelihood method for focus-variation image reconstruction in high resolution transmission electron microscopy. Ultramicroscopy 64, 109–135 (1996).

Meyer, R. R., Kirkland, A. I. & Saxton, W. O. A new method for the determination of the wave aberration function for high resolution TEM: 1. Measurement of the symmetric aberrations. Ultramicroscopy 92, 89–109 (2002).

Hsieh, W.-K., Chen, F.-R., Kai, J. J. & Kirkland, A. I. Resolution extension and exit wave reconstruction in complex HREM. Ultramicroscopy 98, 99–114 (2004).

Zhang, W. et al. Comparative study of SWNCT fluorination by atomic and molecular fluorine. Chem. Mater. 24, 1744–1751 (2012).

Dyck, D. V., Jinschek, J. R. & Chen, F.-R. ‘Big Bang’ tomography as a new route to atomic-resolution electron tomography. Nature 486, 243–246 (2012).

Xu., et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform graphene films on copper foils. Science 324, 1312–1314 (2009).

Zan, R., Ramasse, Q. M., Bangert, U. & Novoselov, K. S. Graphene reknits its holes. Nano Lett. 12, 3936–3940 (2012).

Meyer, J. C. et al. On the roughness of single- and bi-layer graphene membranes. Solid State Commun. 143, 101–109 (2007).

Castro Neto, A. H., Guinea, F., Peres, N. M. R., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109–162 (2009).

Withers, F., Bointon, T. H., Dubois, M., Russo, S. & Craicun, M. F. Nanopattering of fluorinated graphene by electron beam irradiation. Nano Lett. 11, 3912–3916 (2011).

Robertson, A. X. & Warner, J. H. Atomic resolution imaging of graphene by transmission electron microscopy. Nanoscale 5, 4079–4093 (2013).

Çağlar, Ö. G. et al. Graphene at the edge: stability and dynamics. Science 323, 1705–1708 (2009).

Erni, R. et al. Stability and dynamics of small molecules trapped on graphene. Phys. Rev. B 32, 165443 (2010).

Ramirez, A. P. Strongly geometrically frustrated magnets. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 24, 453–480 (1994).

Terrones, H., Lv, R., Terrones, M. & Dresselhaus, M. The role of defects and doping in 2D graphene sheets and 1D nanoribbons. Rep. Prog. Phys. 75, 062501 (2012).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Properties of fluorinated graphene films. Nano. Lett. 10, 3001–3005 (2010).

Lee, S.-S. et al. A mechanistic study of graphene fluorination. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 5407–5415 (2013).

Okotrub, A. V., Babin, K. S., Gusel’nikov, A. V., Asanov, I. P. & Bulusheva, L. G. Interaction of NH3 with the reduced surface of graphite fluoride C2F. Phys. Stat. Sol. B 247, 3039–3042 (2010).

Wilson, N. R. et al. Graphene oxide: stuctural analysis and application as a highly transparent support for electron microscopy. ACS Nano 3, 2547–2556 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank the EPSRC for funding through a studentship for M.A.D. and for a P.D.R.A. Fellowship for R.J.K. and additional support provided by the Warwick Centre for Analytical Science (EP/F034210/1). A.K.G. is indebted to the European Research Council and the Royal Society for financial support. R.R.N. is indebted to the Leverhulme Trust for a Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.J.K., U.B., J.S. and A.K.G. conceived the project. R.R.N., U.B., S.L.W. and R.Z. performed the sample preparation and preliminary transmission electron microscopy characterization of the graphene and fluorographene samples in Manchester. R.J.K. carried out the electron diffraction studies, focal series acquisition and exit wave reconstruction studies in Warwick. Additional EELS studies were performed at the SuperSTEM Laboratory by Q.R. M.A.D. performed additional structure modelling and EWR phase image simulations. J.S., U.B. and R.J.K. wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures, including additional image processing and structure modelling. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-9, Supplementary Tables 1-2 and Supplementary References (PDF 2180 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kashtiban, R., Dyson, M., Nair, R. et al. Atomically resolved imaging of highly ordered alternating fluorinated graphene. Nat Commun 5, 4902 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5902

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5902

This article is cited by

-

Atomically precise graphene etch stops for three dimensional integrated systems from two dimensional material heterostructures

Nature Communications (2018)

-

Fluorination of suspended graphene

Nano Research (2017)

-

Strain and carrier-induced coexistence of topologically insulating and superconducting phase in iodized Si(111) films

Nano Research (2016)

-

All-cis 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexafluorocyclohexane is a facially polarized cyclohexane

Nature Chemistry (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.