Abstract

The tendency of species to retain their ancestral niches may link processes that determine community assembly with biogeographic histories that span geological time scales. Biogeographic history is likely to have had a particularly strong impact on Neotropical forests because of the influence of the Great American Biotic Interchange, which followed emergence of a land connection between North and South America ~3 Ma. Here we examine the community structure, ancestral niches and ancestral distributions of the related, hyperdiverse woody plant genera Psychotria and Palicourea (Rubiaceae) in Panama. We find that 49% of the variation in hydraulic traits, a strong determinant of community structure, is explained by species’ origins in climatically distinct biogeographic regions. Niche evolution models for a regional sample of 152 species indicate that ancestral climatic niches are associated with species’ habitat distributions, and hence local community structure and composition, even millions of years after dispersal into new geographic regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advances in systematic biology have revealed a closer relationship between ecological and biogeographic processes than previously assumed1,2,3,4. The ancestral geographic distributions of organisms might exert lasting influences as they assemble into communities because of a phenomenon known as phylogenetic niche conservatism (PNC)3, in which related taxa retain important aspects of the niche of their common ancestors. Exceptions to this general rule are not uncommon but major evolutionary departures from ancestral niches typically involve instances of geographic or environmental isolation, in which alternative niches are uncontested5,6. In the absence of such isolation or, conversely, in the presence of suitable migration corridors, Donoghue6 and colleagues1,7 have suggested that ‘it is easier to move than to evolve.’ That is, it is more likely for organisms to migrate to habitats for which they are already adapted than to adapt to marginal or novel conditions in situ. This hypothesis has proved useful in explaining broad-scale patterns of biodiversity, such as the latitudinal gradient in diversity (a.k.a. the tropical conservatism hypothesis)1 and the recent radiation of cold-adapted Laurasian, even Himalayan, plant lineages in the Andean cordilleras8. Niche conservatism might also allow geographic history to influence the assembly of ecological communities over shorter time periods and at finer spatial scales9,10,11 if the habitat affinities of species comprising contemporary ecological communities are similar to ancestral ecological niches that evolved in response to environments experienced elsewhere.

The biogeographic history of Neotropical forests has been dominated by two geologically recent events12,13. The uplift of the northern Andean cordilleras (25–3 Ma)14 increased the climatic diversity of northwestern South America12, whereas the subsequent emergence of the Isthmus of Panama at ~3 Ma15 made possible the Great American Biotic Interchange (GABI), which brought species with a history of selection in climatically distinct geographic regions into contact with novel environments and into competition with natives as well as co-immigrants.

If functional traits have tended to evolve in situ in response to selection pressure exerted by the local environment and community, taxa are likely to have departed from ancestral niches and show little evidence of PNC. Alternatively, if species tend to track preferred microenvironments after dispersal to new regions, then local species composition may reflect the geographic history of species or lineages before the interchange. These alternative assembly mechanisms have important implications for our understanding of species coexistence in tropical forests, which have proved an enduring challenge to ecological theory. Neutral theory posits that niche differences are unimportant relative to stochastic drift and immigration16. Counter examples point to subtle but pervasive niche differences as evidence that communities are structured by competition, character displacement and limiting similarity17. If such niche differences are contingent upon historical geographic mixing rather than in situ character evolution, it may suggest that the stabilizing effect of those niche differences has a smaller role in community assembly than commonly assumed.

Here we address three questions concerning the influence of biogeographic history on the assembly of communities. Do species distributions in an environmentally heterogeneous locality reflect the geographic origins of member taxa? Was niche evolution significantly influenced by the geographic history of phylogenetic lineages? And finally, has the GABI enhanced phylogenetic and functional trait diversity in Neotropical tree communities?

To address these questions, we examine the biogeographic history, trait evolution and community structure of members of two closely related and hyperdiverse genera Psychotria L. and Palicourea Aubl. (Rubiaceae), which comprise ~2,300 tropical woody plant species, including ~1,000 species in the Neotropics18. We find that ~50% of the variation in hydraulic traits, a strong determinant of community structure, is explained by species’ origins in climatically distinct biogeographic regions. Niche evolution models for a regional sample of 152 species indicate that ancestral climatic niches are associated with species’ habitat distributions, and hence local community structure and species composition, even millions of years after dispersal into new geographic regions.

Results

Microhabitat patterns reflect biogeographic history

We have shown previously that assemblages of Psychotria and Palicourea found co-occurring within 134 small, 3-m-radius plots on Barro Colorado Island (BCI), Panama, are more closely related than expected by chance (that is, are phylogenetically clustered)19. This pattern appears to be driven by habitat-filtering mediated by phylogenetically conserved hydraulic traits that influence a species’ tolerance of seasonal drought19.

To determine whether local microhabitat patterns reflect biogeographic history, we first determined the ancestral geographic distributions20 of all nodes in a 203-taxon phylogeny of the tribe Psychotrieae (Fig. 1, see Methods). Nearly all Neotropical Psychotria found in Central and northern South America descend from a single lineage that diversified in Central America. Palicourea originated in northern South America and shows evidence of several mid-Miocene (12–15 Ma) dispersal events into the Northern Andes and into the trans-Andean biogeographic region comprising the Chocó of western Colombia and the Panamanian Darién (Fig. 1a). In addition, some Andean Palicourea appear to have dispersed into Central America as long ago as 8 Ma. Many of the extant taxa we analysed are widespread (Supplementary Fig. S1); their geographic origins were inferred from the distributions of less widespread relatives20.

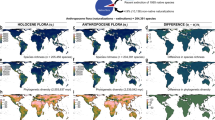

The relationship of habitat distribution and hydraulic traits is indicated with respect to climatic niche and biogeographic region of origin among 20 Psychotria and Palicourea of BCI. (see Methods for discrepancy between clades and taxonomic nomenclature) (a) Ancestral area reconstruction. Branch colour indicates the geographic region in which the branch originated. (b) Canonical correspondence analysis of the habitat distributions of the 15 most abundant species censused in 134 3-m-radius plots on BCI19 showing soil moisture and light as important correlates of species composition. Abbreviations for species following complete names are provided in a and their colour indicates the species’ geographic region of origin (c) PGLS linear regression of species climatic niche with respect to PC3 and PGLS analysis of variance of geographic origin versus species-weighted mean distribution with respect to soil moisture on BCI and leaf water potential at turgor loss (ψt); λ indicates phylogenetic signal.

By comparing geographic origins with local microhabitats, we find that nearly 50% of the variation in species soil moisture distribution on BCI is explained by differences in the biogeographic area of origin of the study taxa (Fig. 1b,c). Likewise, biogeographic origin explains 51% of the variation in leaf water potential at turgor loss (ψt) among the BCI species (Fig. 1c). These associations suggest that by filtering species with similar hydraulic traits, fine-scale soil moisture environments on BCI effectively segregate species of Psychotria and Palicourea with shared biogeographic histories.

To further examine the association between geographic history and microhabitat preferences, we investigated broad climatic niche differences among species that may, in turn, reflect climatic differences between Neotropical geographic regions. We conducted a principal component analysis of species distributions with respect to 20 climatic variables (see Methods). Four principal components (PCs) explain 94% of the variation in climatic niche (Table 1). PC1, defining 46% of the variance, is largely defined by elevation and associated temperature variables, whereas PC2, comprising 27% of climatic niche variance, largely reflects a latitudinal gradient in temperature seasonality (Table 1).

The PC3 axis is largely explained by precipitation and precipitation seasonality, comprising a gradient between dry, seasonal climates and wetter, less seasonal ones (Table 1). Although PC3 defines only 12% of the variance in species regional distributions, it provides the most insight regarding microhabitat distributions on BCI. Species that tolerate very negative leaf water potentials (ψt) and occur in dry microsites on BCI have significantly more positive scores along PC3 (Fig. 1c). This result suggests that species distributions with respect to regional climatic gradients, such as those defined by precipitation, are representative of their distributions with respect to local environmental variation, such as soil moisture heterogeneity21, providing a potential causative link between geographic history and local community composition.

Geographic history influences hydraulic niche evolution

To test whether geographic history has constrained niche evolution of Psychotria and Palicourea, we compared the relative fit of eight alternative models of climatic niche evolution22. Three models represent scenarios in which geographic regions have had no influence on species’ climatic niches (Fig. 2a–c). Alternatively, if geographic history has left a signature, it may be reflected in the parameter θ, the ‘optimum’ niche towards which species are selected in a model of random walk with stabilizing selection22. If climatic niches are strongly conserved, broad clades may be fit by a single value of θ that reflects the climate of the region in which lineage diversification took place (‘clade history’ models Fig. 2d–f). Finally, if climatic niche evolution has occurred on a timescale commensurate with that of the changing geographic history of the taxa, climatic niches may have evolved with respect to a θ defined by the region in which each species originated (the ‘taxon history’ model, Fig. 2g). We also examined a variant of the ‘taxon history’ model in which the only meaningful regional differences were between Andean and non-Andean regions (the ‘Andes history’ model, Fig. 2f).

Log-likelihoods and size-corrected Akaike information criterion (AIC) weights are shown for models pertaining to climatic niche axis PC3. Complete results for all four PCs are shown in Table 2. (a) The Brownian motion model in which species randomly drift from the niche of their ancestors39, (b) the Ornstein–Uhlenbeck model of random drift with stabilizing selection in which selection increases as species drift further from a single optimal climatic niche22, (c) a ‘white noise’ model of evolution, in which species’ climatic niches are drawn from a normal distribution without regard to their phylogenetic relationships or geographic history40, (d–f) random drift with stabilizing selection towards one of several optimal niches that differ between clades with distinct geographic histories, (g) model in which species climatic niches evolve with respect to an optimum niche defined by the geographic region in which each taxon originated and (h) a variant of G in which the only meaningful differences are between Andean and non-Andean regions. Model G is the best-fit model.

Niche evolution with respect to PC3 is best characterized by the ‘taxon history’ model (Fig. 2g) in which the selection optimum reflects the region of origin of each taxon in the phylogeny. Broad climatic differences between major regions of the Neotropics appear to influence the niche evolution of Psychotria and Palicourea, and to continue their association with the habitat distributions of widespread species after dispersal to new regions.

Community assembly and the GABI

To assess the generality of the patterns observed on BCI, we examined the geographic origins of the Psychotria and Palicourea assemblages documented at 13 sites across the Neotropics (Fig. 3). The seven South American sites are dominated by lineages with South American origins, whereas the four Central American moist forests are inhabited by lineages with a long history in Central America and by relatively recent immigrants from South America (Fig. 3a). Central American dry forests appear species poor and largely devoid of Palicourea.

Geographic history and species composition are shown in a where the colours indicate ancestral areas of origin. The upper clade is ‘Psychotria’. The contribution of immigrants within the last 3 Ma to the phylogenetic (b) and functional (c) diversity of each site reveals phylogenetic and functional asymmetry in the GABI23. Floristic inventories of each site can be found in Supplementary Table S1. The region in which each site is located is indicated at the bottom of a.

The contribution of immigration within the last 3 Ma to the phylogenetic diversity of each site differs significantly by region (Fig. 3b). The diversity of the four Central American moist forests is substantially more affected than that of sites east of the Andes (P<0.0001; t-test) or in South America in its entirety (P<0.0001). The effect on functional diversity as reflected in species climatic niches relative to PC3 is less substantial (Fig. 3c). Recent immigrants to sites east of the Andes appear to be functionally redundant with natives, whereas the effect varies widely among the four Central American moist forests, perhaps because of the influence of South American immigration before the closure of the land bridge (Figs 1a and 3a).

Discussion

Our results indicate that the hydraulic traits and microhabitat niches of the Psychotria and Palicourea of BCI are associated with the region of origin of species before dispersing to central Panama during the GABI. This result suggests that the filtering of species with similar hydraulic traits over fine-scale soil moisture gradients on BCI not only results in phylogenetically clustered assemblages19 but also effectively selects species of Psychotria and Palicourea with a shared biogeographic and climatic history.

An examination of the geographic origins of the Psychotria and Palicourea recorded in 13 Neotropical forests suggests that the contribution of the GABI to local community composition has been widespread in humid Central America, but much less pervasive in South American forests, even those west of the Andes (Fig. 3), a pattern noted by botanists for the broader Neotropical flora23. What has not been recognized previously is that recent biogeographic admixture has probably increased the phylogenetic and functional diversity of Central American forests relative to areas less influenced by the GABI. These results suggest that, because of the prevalence of ecologically conservative dispersal in community assembly, the phylogenetic and functional structure of local communities depend on the phylogenetic and climatic diversity of the source pool from which the communities were assembled, making community structure and function a product of biogeographic exchange11,13,15.

The spatial scale at which community structure reflects the geographic history of species of Psychotria and Palicourea on BCI is striking. Associations between biogeographic history and large-scale climatic or macrohabitat preferences have been observed in plants in the Valerianaceae8 and in Emydid turtles9. In contrast, the hydraulic niches that characterize Psychotria and Palicourea with a common centre of origin differentiate species on a scale of only a few metres in the forest understory19, and therefore bring biogeographic assembly into a spatiotemporal scale that is commensurate with competition and ecological coexistence.

Understanding the coexistence of hundreds, even a thousand, of species of woody plants in some tropical forests has proved an enduring challenge and has stimulated some of the most influential, and controversial, theories of coexistence and community assembly24,25. Hubbell’s16 Neutral theory posits that the stabilizing effect of species niche differences is less important than demographic stochasticity and immigration in the assembly of communities. Meanwhile, evidence of pervasive, although subtle, trait dispersion in communities may support a role for resource- and regeneration-based niche differences in stabilizing species coexistence17. If the hydraulic niches considered here were strongly governed by interactions that limit the similarity of co-occurring species or otherwise favoured the exploitation of unoccupied niche space, in situ character evolution would be expected to erase the signature of a biogeographic interchange that took place 3 Ma. In contrast, our results suggest that hydraulic niche differences and their prevalence in tropical forest communities may be strongly influenced by historical contingency, making community structure and the niche differences of co-occurring species a product of biogeographic processes such as changes in dispersal barriers and corridors that connect regions with unique climates. If the patterns exhibited by two hyperdiverse genera of Rubiaceae pertain to other species-rich plant genera23, it would suggest that hydraulic niches, and possibly other easily measured trait dimensions, contribute relatively little to the stabilization of coexistence in tropical forest communities24. On the other hand, other niche dimensions may strongly stabilize coexistence, including those pertaining to interactions with natural enemies26. It remains unclear to what extent the major resource- and enemy-defined niche dimensions of tropical trees are characterized by in situ evolution or PNC.

Our results indicate that the comparatively slow rate of niche evolution relative to changes in geographic distribution has left a notable historical signature on the community structure of one of the most diverse plant clades on the planet, particularly where biogeographic interchange has been recent and pervasive as a result of the GABI. The importance of geographic mixing for the niche structure of Neotropical communities further suggests that widespread niche differences among co-occurring tropical trees may owe as much to the history of dispersal as to selection for niche segregation imposed by competitive interactions.

Methods

Taxonomy versus Clades

The taxonomy of the Psychotrieae does not yet reflect recent findings in molecular phylogenetics, which indicate that the generic name Psychotria comprises a polyphyletic group of species18,27. Here we employ ‘Psychotria’ to refer to the Psychotria subgroup Psychotria clade and ‘Palicourea’ to refer to the clade comprising Palicourea plus Psychotria subgroup Heteropsychotria (that is, Palicourea s. lat.). These two groups represent 208 and 803 species, respectively, in the Neotropics ( http://www.tropicos.org).

Molecular methods and phylogenetic reconstruction

We compiled 247 internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences from Psychotrieae and outgroup species for analysis. These ITS sequences included all Psychotrieae species represented in GenBank as of 30 October 2011, as well as close relatives used for outgroups, species studied by Paul et al.28 and 26 new Psychotrieae ITS sequences. New sequences were generated following protocols described in the Supplementary Methods and sequenced in both directions at the University of Chicago Cancer Research Center. We discarded a subset of GenBank sequences that could not be reliably attributed to a verified species.

We aligned the 273 sequences using the MUSCLE algorithm29 executed in Geneious 5.1.7 (ref. 30)30. The resulting 856 bp alignment was then used to reconstruct the phylogeny in a Bayesian framework based on a general time reversible model of molecular evolution, with gamma-distributed rate variation and a proportion of invariable sites. We ran two concurrent runs of four chains on MrBayes v3.1.2 (ref. 31)31, via the CIPRES web portal32, for 5 × 106 generations, sampling parameters every 100 generations and a burn-in of 5 × 104. A chronogram was generated using a PATHd8 (ref. 33)33 age-estimation of the 50% majority rule Bayesian consensus tree, with the most recent common ancestor of the Psychotrieae alliance fixed at 48.7 Ma and the crown node of the Psychotrieae fixed at 35.6 Ma34.

Ancestral area reconstruction

We reconstructed the evolution of geographic ranges in the Neotropical Psychotrieae using the maximum likelihood dispersal-extinction-cladogenesis model of Ree and Smith20, as implemented in ‘Lagrange’. We employed an unconstrained but temporally stratified model in which the Andes region was not available for dispersal until the oldest estimate of their origination around 25 Ma14. Dispersal probabilities between regions were assumed to be symmetric.

The following five biogeographic regions were used in the analysis: (a) Central America and the Caribbean, (b) the Trans-Andes lowland forest comprising the Chocó region of western Colombia and Ecuador, the Darién region of eastern Panama and Magdalena Valley in Colombia; (c) the Andes at elevations >1,500 m; (d) the Amazon Basin, Guyana Highlands and eastern Brazil; and (e) Paleotropics, encompassing Asia, Africa and Pacific islands (Fig. 1, inset). Alternative analyses in which distinct northern and central Andes regions were separated at the Huancabamba gap following Gentry23 differed little from results shown here because only a single species in our sample is restricted to the central Andes. The Andean region is separated here from the Amazonian and Chocó-Darién regions at ~1,500 m based on recent, extensive floristic study of Rubiaceae in this region18,35,36. As the lower limits of montane forest vary locally, species are characterized as Andean or lowland based on the predominant area of their occurrence. Lastly, lowland savanna regions of northern Colombia and Venezuela and lowland xeric environments of coastal Peru and Chile (grey areas in Fig. 1, inset) were ignored in our analyses.

Climatic data

A total of 21,115 georeferenced herbarium specimens pertaining to 152 species catalogued at the Missouri Botanical Garden ( http://www.tropicos.org) were mapped using ArcCatalog 10.0 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA; mean=140 records per species, range=3–1263). For each record, we extracted values for elevation and 19 climatic variables from the WorldClim database at 30-s resolution37. The species mean for each of the 20 variables was calculated and a principal component analysis performed on 152 species pertaining to the Neotropical Psychotria and Palicourea, or ~15% of the combined hemispheric diversity of the two genera18. PC1–PC4 explained more variation than expected, based on a broken-stick distribution38 for a total of 94%, and so were used in subsequent analyses. The first three PCs appear to describe geographic gradients in elevation, latitude and precipitation, respectively, based on the loadings of climatic variables (Table 1).

Phylogenetic comparative analysis and climatic niche evolution

We compared a series of eight alternative models that reflect alternative hypotheses concerning the influence of geographic history on niche evolution: a Brownian motion model39, an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck model with a single selection optimum θ, a ‘white noise’ model in which species niches are independent of phylogeny40 and five additional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck models in which θ was allowed to undergo a shift at phylogenetic nodes associated with historic dispersal events22 (Fig. 2). The nodes subtending each of four clades with broadly distinct biogeographic histories were identified as candidates for optimum shifts, so that the most complex model included a distinct θ parameter for each of the four geographic regions plus the parameters σ2 (strength of drift) and α (strength of selection) for a total of six parameters. Evolution models were fit independently for each of the four PC axes using the R package ‘ouch’22 and compared using size-corrected Akaike information criterion weights. Evolution models for PC1–PC4 can be found in Table 2.

Statistical analysis

We employed phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS) linear regression to examine the relationship between species PC factor scores and hydraulic traits and soil moisture distributions among the 20 species occurring on BCI using the ‘caper’ package in R41,42. Pagel’s43 λ was estimated for PC3 with respect to the regional phylogeny of 147 taxa, and the maximum likelihood value 0.063 was used for subsequent PGLS linear regression of PC3 on local soil moisture distribution among the BCI species. PGLS analysis of variance with simultaneous maximum likelihood estimation of Pagel’s λ was used to analyse the proportion of variation in local soil moisture preferences and hydraulic traits explained by geographic centre of origin for the Psychotria and Palicourea found on BCI.

Community structure and the GABI

To assess the generality of the patterns observed on BCI, we examined the geographic origins of the Psychotria and Palicourea assemblages documented at 13 sites across the Neotropics (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S1). We measured the contribution of immigration within the last 3 Ma to phylogenetic diversity at each site by comparing Faith’s44 phylogenetic diversity metric (PD) with respect to the native flora to a distribution of expected PD pertaining to samples of equal species richness of the extant flora of each site using the R package ‘picante’45. In addition, we estimated the contribution of recent South American immigrants to the functional diversity of each site by measuring the variance of native species factor scores relative to PC3 with the variance expected from samples of equal species richness of the extant flora of each forest site. We more directly measured the influence of the GABI on the functional diversity of BCI by conducting the same procedure with respect to species soil moisture habitat distributions and hydraulic traits. In both types of analysis, we interpreted the negative of the standardized effect size as a measure of phylogenetic or functional diversity.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Sedio B. E. et al. Fine-scale niche structure of Neotropical forests reflects legacy of the Great American Biotic Interchange. Nat. Commun. 4:2317 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3317 (2013).

References

Wiens, J. J. & Donoghue, M. J. Historical biogeography, ecology and species richness. Trends. Ecol. Evol. 19, 639–644 (2004).

Ricklefs, R. E. A comprehensive framework for global patterns in biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 7, 1–15 (2004).

Wiens, J. J. et al. Niche conservatism as an emerging principle in ecology and conservation biology. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1310–1324 (2010).

Ricklefs, R. E. Disintegration of the ecological community. Am. Nat. 172, 741–750 (2008).

Baldwin, B. G. & Sanderson, M. J. Age and rate of diversification of the Hawaiian silversword alliance (Compositae). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 9402–9406 (1998).

Donoghue, M. J. A phylogenetic perspective on the distribution of plant diversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 11549–11555 (2008).

Ackerly, D. D. Community assembly, niche conservatism, and adaptive evolution in changing environments. Int. J. Plant. Sci. 164, S165–S184 (2003).

Bell, C. D. & Donoghue, M. J. Phylogeny and biogeography of Valerianaceae (Dipsacales) with special reference to the South American valerians. Org. Divers. Evol. 5, 147–159 (2005).

Stephens, P. R. & Wiens, J. J. Convergence, divergence, and homogenization in the ecological structure of emydid turtle communities: The effects of phylogeny and dispersal. Am. Nat. 164, 244–254 (2004).

Moen, D. S., Smith, S. A. & Wiens, J. J. Community assembly through evolutionary diversification and dispersal in Middle American treefrogs. Evolution 63, 3228–3247 (2009).

Dexter, K. G., Terborgh, J. W. & Cunningham, C. W. Historical effects on beta diversity and community assembly in Amazonian trees. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7787–7792 (2012).

Hoorn, C. et al. Amazonia through time: Andean uplift, climate change, landscape evolution, and biodiversity. Science 330, 927–931 (2010).

Antonelli, A. J., Nylander, J. A. A., Persson, C. & Sanmartin, I. Tracing the impact of the Andean uplift on Neotropical plant evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 9749–9754 (2009).

Parra, M. et al. Orogenic wedge advance in the northern Andes: evidence from the Oligocene-Miocene sedimentary record of the Medina Basin, Eastern Cordillera, Colombia. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 121, 780–800 (2009).

Coates, A. G. & Obando, J. A. inEvolution and Environment in Tropical America eds Jackson J. B. C., Budd A. F., Coates A. G. 21–56University of Chicago Press (1996).

Hubbell, S. P. The Unified Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography Princeton University Press (2001).

Kraft, N. J. B., Valencia, R. & Ackerly, D. D. Functional traits and niche-based tree community assembly in an Amazonian forest. Science 322, 580–582 (2008).

Taylor, C. M. Overview of the Psychotrieae (Rubiaceae) in the Neotropics. Opera Bot. Belg. 7, 261–270 (1996).

Sedio, B. E., Wright, S. J. & Dick, C. W. Trait evolution and the coexistence of a species swarm in the tropical forest understorey. J. Ecol. 100, 1183–1193 (2012).

Ree, R. H. & Smith, S. A. Maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction, and cladogenesis. Syst. Biol. 57, 4–14 (2008).

Engelbrecht, B. M. J. et al. Drought sensitivity shapes species distribution patterns in tropical forests. Nature 447, 80–83 (2007).

Butler, M. A. & King, A. A. Phylogenetic comparative analysis: a modeling approach for adaptive evolution. Am. Nat. 164, 683–695 (2004).

Gentry, A. H. Neotropical floristic diversity: Phytogeographical connections between Central and South America, Pleistocene climatic fluctuations, or an accident of the Andean orogeny? Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 69, 557–593 (1982).

Wright, S. J. Plant diversity in tropical forests: a review of mechanisms of species coexistence. Oecologia 130, 1–14 (2002).

Leigh, E. G. et al. Why do some tropical forests have so many species of trees? Biotropica 36, 447–473 (2004).

Kursar, T. A. et al. The evolution of antiherbivore defenses and their contribution to species coexistence in the tropical tree genus Inga. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 18073–18078 (2009).

Davidse, G., Sousa, S. M., Knapp, S., Chiang, F. & Ulloa Ulloa, C. Flora Mesoamericana Rubiaceae 4.2 Missouri Botanical Garden Press (2012).

Paul, J. R., Morton, C., Taylor, C. M. & Tonsor, S. J. Evolutionary time for dispersal limits the extent but not the occupancy of species’ potential ranges in the tropical plant genus Psychotria (Rubiaceae). Am. Nat. 173, 188–199 (2009).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792 (2004).

Drummond, A. J. et al. Geneious v5.1 available from http://www.geneious.com/ (2011).

Ronquist, F. & Huelsenbeck, J. P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572 (2003).

Miller, M. A. et al. The CIPRES Portals. CIPRES .http://www.phylo.org/sub_sections/portal (accessed on 31 October 2011) (2011).

Britton, T., Anderson, C. L., Jacquet, D., Lundqvist, S. & Bremer, K. Estimating divergence times in large phylogenetic trees. Syst. Biol. 56, 741–752 (2007).

Bremer, B. & Eriksson, T. Time tree of Rubiaceae: phylogeny and dating the family, subfamilies, and tribes. Int. J. Plant Sci. 170, 766–793 (2009).

Taylor, C. M. inCatalogue of the Vascular Plants of Ecuador (eds Jørgensen P. M., León S. Monagr. Syst. Bot. Missouri Bot. Gard. 75, 855–878 (1999).

Taylor, C. M. et al. Rubiaceae in Flora of the Venezuelan Guayana eds Steyermark J. A., Berry P. E., Yatskievych K., Holst B. K. 497–847Missouri Botanical Garden (2004).

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G. & Jarvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965–1978 (2005).

Jackson, D. A. Stopping rules in principal components analysis: a comparison of heuristical and statistical approaches. Ecology 74, 2204–2214 (1993).

Felstenstein, J. Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am. Nat. 125, 1–15 (1985).

Harmon, L. J., Weir, J. T., Brock, C. D., Glor, R. E. & Challenger, W. GEIGER: investigating evolutionary radiations. Bioinformatics 24, 129–131 (2008).

Orme, C. D. L. et al. Caper: comparative analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R. R package version 0.5 .http://www.CRAN.R-project.org/package=caper (2012).

Revell, L. J. Phylogenetic signal and linear regression on species data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1, 319–329 (2010).

Pagel, M. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature 401, 877–884 (1999).

Faith, D. P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol. Cons. 61, 1–10 (1992).

Kembel, S. W. et al. Picante: tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 26, 1463–1464 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Magill, R. Foster and the Environmental and Conservation Program of the Field Museum, as well as D. Lorence and the National Tropical Botanical Garden whose botanical collections made this study possible. We also thank A. King, S. Smith, D. Goldberg, J. Wright, J. Bemmels, the Angert Lab and the University of Michigan Plant Ecology Discussion Group for intellectual input, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute for support of the original fieldwork on Barro Colorado Island and J. Megahan for assistance with the artwork. This study was facilitated by the support of NSF DEB 1010816 and an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship to B.E.S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.E.S. conducted the ancestral area reconstruction, climatic niche reconstruction, niche evolution modelling and diversity analyses, and led the writing of the manuscript. J.R.P conducted the molecular lab work and phylogenetic analyses. C.M.T. conducted the taxonomic classification and specimen verification. B.E.S., J.R.P., C.M.T. and C.W.D. discussed the experimental design and results and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figure S1, Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 1131 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sedio, B., Paul, J., Taylor, C. et al. Fine-scale niche structure of Neotropical forests reflects a legacy of the Great American Biotic Interchange. Nat Commun 4, 2317 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3317

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3317

This article is cited by

-

Biotic interchange between the Indian subcontinent and mainland Asia through time

Nature Communications (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.