Abstract

Investigating the cellular internalization pathways of single molecules or single nano objects is important to understanding cell–matter interactions, and to applications in drug delivery and discovery. Imaging and tracking the motion of single molecules on cell plasma membranes require high spatial resolution in three dimensions. Fluorescence imaging along the axial dimension with nanometre resolution has been highly challenging, but critical to revealing displacements in transmembrane events. Here, utilizing a plasmonic ruler based on the sensitive distance dependence of near-infrared fluorescence enhancement of carbon nanotubes on a gold plasmonic substrate, we probe ~10 nm scale transmembrane displacements through changes in nanotube fluorescence intensity, enabling observations of single nanotube endocytosis in three dimensions. Cellular uptake and transmembrane displacements show clear dependences to temperature and clathrin assembly on cell membrane, suggesting that the cellular entry mechanism for a nanotube molecule is via clathrin-dependent endocytosis through the formation of clathrin-coated pits on the cell membrane.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interactions of molecules and nanostructured materials with mammalian cells have aroused a great deal of scientific interest with implications to many biological and medical applications in drug discovery, nanomedicine and toxicology1. The uptake pathway and subsequent intracellular trafficking have been intensely studied and debated for a broad range of nanomaterials, including fullerene2, quantum dots3, magnetic nanoparticles4 and carbon nanotubes (CNTs)5,6,7. An interesting question is in regards to the cellular internalization pathways and the dependence of the pathways on the size of molecules or nanomaterials. It is important to investigate the upper size limit for molecules simply inserting and diffusing through the cell plasma membrane, and the lower size limit for nanomaterials becoming too small for wrapping by a highly curved lipid bilayer to undergo endocytosis.

As an example, two distinct pathways for CNT cellular entry have been suggested, direct insertion or diffusion through the lipid bilayer5,8,9,10, and clathrin-dependent endocytosis6,11,12,13. Most studies used ensembles of CNTs (including bundles and aggregates of tubes) in cellular uptake experiments through imaging of fluorescent dye labels5,6 and have suggested endocytotic internalizations of CNTs6,13,14, except in several reports proposing direct insertion5,8. At the individual nanotube level, imaging CNT–cell interactions through detecting the intrinsic near-infrared (NIR) photoluminescence (PL)7,15 of CNTs has been performed. However, thus far, there has been no direct three-dimensional (3D) imaging of single nanotube molecules traversing cell membrane to directly observe either insertion or endocytosis pathway. In a theoretical study, Gao et al.16 suggested high curvature of cargo particles, such as a bare single-walled CNT (diameter down to 1 nm), could cause elevated elastic energy associated with lipid-bilayer wrapping involved in endocytosis, and an optimum radius of curvature of ~14 nm exists for endosome formation around a cylindrical particle. The question of whether an individual CNT (rather than bundles or aggregates of tubes) can undergo endocytosis remains an interesting open problem.

Imaging and tracking single events of specific molecules on cell membrane can offer new insights into various mechanisms of interest to biological systems17. Imaging single-molecule transmembrane motion requires nanometer spatial resolution along the axial dimension. Recent progresses in 3D single particle tracking have led to various new techniques to resolve the location of a single nanoparticle with high precision and elucidate interactions between the tracked nanoparticle with its surroundings18. For instance, by confining illumination to a ~100 nm optical section with evanescent waves travelling at the cover slip–cell interface, total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy has been developed to image cell membrane, nearby cytoplasm and membrane-related events19. Further, combined with two-dimensional (2D) super-resolution techniques20, high axial resolution can also be achieved by imposing z-dependent asymmetry into two orthogonal axes x and y21,22, or using two stimulated emission depletion beams to generate a central zero in three dimensions23. Single-molecule axial tracking has also been realized by feedback tracking, including focusing two circularly scanning laser beams at different z-depths24. Still, it remains highly challenging to image transmembrane motion of a single molecule (such as a single nanotube) with sensitivity on the order of the thickness of the plasma membrane (~10 nm), thus probing the pathway and kinetics of single-molecule transportation across the plasma membrane.

Here we report the use of an NIR fluorescence enhancement (NIR-FE) phenomenon on plasmonic gold substrates25,26,27,28 to track cellular internalization of individual single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs) in 3D, with an axial resolution on the order of ~10 nm owing to the highly sensitive dependence of FE to the distance between SWCNT and gold25. SWCNTs exhibit intrinsic band-gap fluorescence in the 0.9–1.4 μm NIR II region upon excitation in the visible or NIR I (600–900 nm)29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Recently, we observed FE of SWCNTs by >10-fold on a solution-phase-grown gold films (called Au/Au films) containing patchworks of nanostructured Au islands. The FE rapidly decreases as the distance between SWCNT and Au increases, with an exponential decay distance (1/e decay distance) of a mere ~6 nm25,27. By taking advantage of this interesting effect, we demonstrate single-molecule transmembrane imaging with high sensitivity to axial motion and elucidate the cellular internalization pathway for individual nanotubes.

Results

Plasmonic ruler based on FE

We used water-soluble, high-pressure CO conversion (HiPCO) SWCNTs (diameter ~0.7–1 nm) in our cell-entry imaging experiments. The nanotubes were stably suspended by mixed surfactants of 75% C18-PMH-mPEG (poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-octadecene)-methoxy(polyethyleneglycol (PEG), 5,000; 5 kDa for each PEG chain, 90 kDa in total) and 25% DSPE-PEG (5 kDa)-NH2 (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethyleneglycol, 5,000)] (see Methods)), with amine groups covalently conjugated with arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) peptide ligands capable of selectively binding to αvβ3-integrin overexpressed on U87-MG glioblastoma cells38. As the radius of gyration of a 5 kDa PEG chain is ~3.5 nm in aqueous solution39, a water-soluble SWCNT is wrapped by a ~7-nm thick polymer coating radially to form a cylinder with ~15 nm diameter (inset of Fig. 1b), greater than the diameter of ~1 nm of bare nanotubes. Atomic force microscope (AFM) imaging of SWCNTs on glass substrate after calcination showed most nanotubes lying horizontally with an average length of ~1 μm (Supplementary Fig. S1). We found that the length distribution did not affect the major results of our experiments (Supplementary Fig. S2), suggesting a general nanoscopic 'ruler' applicable to different lengths of SWCNTs.

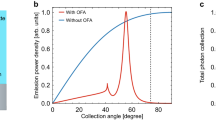

(a) An SEM image of the plasmonic Au/Au film used for enhancing the fluorescence of SWCNTs in this work. The scale bar indicates 500 nm. Inset shows the ultraviolet-Vis-NIR extinction spectrum for the same film with a plasmonic resonance peak at ~800 nm. (b) Fluorescence enhancement factor of SWCNTs as a function of distance between SWCNTs and the enhancing Au/Au film showing a 1/e decay distance of ~6 nm. Data are shown as black squares with error bars obtained by taking the s.d. of all 319×256 pixels in the field of view (690 μm by 860 μm), whereas a fit to first-order exponential decay is shown in red curve. The schematic shows how a single nanotube (red cylindrical core) wrapped with polymer coating (cyan shell) is separated from the Au/Au film by an Al2O3-spacing layer with a certain thickness d. RGD peptide ligands are shown in green triangles. (c) Emission spectrum of a fluorescence-enhanced single CNT under excitation at 658 nm, showing a peak at 1,149 nm. The nanotube is assigned to the (7,6) chirality. Inset: overlay of fluorescence image and white-light U87-MG cell image (outlined by the dashed line) showing the single tube on the cell membrane at the proximal side to the Au/Au film. (d) Polarization dependence of the photoluminescence (PL) intensity of the SWCNT in (c). Error bars were obtained by taking the s.d. of the brightest and eight surrounding pixels that make up the single nanotube image. Inset shows that the angle of polarization is defined as the angle between the electric field vector of polarized excitation light and the nanotube axis.

Figure 1a shows a scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of an NIR fluorescence enhancing Au/Au film comprised of gold nano islands with abundant gaps in between. The ultraviolet-Vis-NIR extinction spectrum of the same Au/Au film (Fig. 1a inset) shows a plasmon resonance peak located at ~800 nm, facilitating FE in the NIR region40. To reveal the distance dependence of FE, we coated the Au/Au films with progressively thicker Al2O3 by atomic layer deposition (ALD), and deposited nanotubes on the substrates by drop-drying an aqueous nanotube suspension. The surface density of nanotubes within the drop-dried spot can be seen from the AFM image in Supplementary Fig. S1. Comparing the nanotube fluorescence intensity on Au/Au films with different spacer thicknesses with that on bare glass, we found a decreasing trend of enhancement factor, from ~8-fold enhancement to almost no enhancement, as the spacer increases in thickness (Fig. 1b). The exponential fit showed a surprisingly short 1/e decay distance of ~6 nm, considering the average length of our SWCNTs is much greater, ~1 μm. As the nanotubes are long and may not lie perfectly flat on the substrate, the separation of any part of a long tube from the gold surface is greater than or equal to the thickness of Al2O3 spacer. For this reason, we suggest that the measured enhancement versus distance data corresponds to the minimum distance between Au and the length of a nanotube in case when the nanotube is non-parallel to the Au surface.

3D tracking of single nanotubes at 37 °C

We exploited the ultrasensitive FE of SWCNTs to gold-nanotube distance for probing the motion of nanotubes in the direction normal to the gold surface. We stained trypsinized U87-MG cells at 4 °C by highly diluted SWCNTs (~20 pM) with PEG and RGD functionalization and placed the cells on an Au/Au substrate kept at 4 °C. Imaging with an InGaAs 2D detector (excitation ~658 nm) in the 1.1–1.7 μm emission range revealed a brightly fluorescent spot overlaying with a single cell (Fig. 1c inset), attributed to a single nanotube sandwiched between Au/Au and cell membrane on the proximal side to the substrate (see Supplementary Fig. S3 for further evidence of bright nanotubes sandwiched between cell and Au), exhibiting strong NIR-FE due to proximity to the gold surface27. Because of trypsinization and staining at 4 °C to prevent unwanted endocytosis before tracking started, most cells lost the extracellular matrix and turned into round shape, but they still remained viable and could internalize nanomaterials from the outside once temperature was raised27. We identified the single nanotube by one single peak in the emission spectrum (~1,150 nm in Fig. 1c, corresponding to (7,6) chirality) and the sinusoidal dependence41 of fluorescence on the polarization of laser excitation (Fig. 1d).

Once an individual nanotube was identified, we increased the incubation temperature from 4 to 37 °C in situ and tracked the fluorescence of the SWCNT over time at a frame rate of 0.3 frame per second after the temperature stabilized at 37 °C. The (7,6) tube in Fig. 1c showed a clear fluorescence intensity decrease over time (Fig. 2b–d, extracted from Supplementary Movie 1) with motion in the 2D imaging plane on the cell membrane (see Fig. 2a and bottom left panel of Supplementary Movie 1). By plotting the fluorescence intensity of this tube as a function of time, we observed an exponential decrease with a 1/e decay time of ~121 s following some fluctuations at the beginning. Two other independent tracking experiments were carried out under the same condition and similar fluorescence decreases were observed (Supplementary Fig. S4i–l) with 1/e decay times of ~103 and ~111 s, respectively.

(a) A 2D trajectory of a single CNT (same as the one in Fig. 1c,d) moving on the cell membrane during endocytosis at 37 °C. (b–d) Photoluminescence (PL) images of this particular single CNT overlaid with optical images of a cell (outlined by the dashed line) at three time points: 20, 73.3 and 263.3 s after the incubation temperature stabilized at 37 °C. Rectangular red bar on the bottom left of each image indicates relative fluorescence intensity. Intensity scale bar on the right indicates red as the highest signal, whereas blue as the lowest after normalization. (e) PL intensity (black squares) of this single nanotube plotted as a function of time at 37 °C and fitted to a first-order exponential decay shown in red curve with a 1/e decay time of 121 s. (f–h) Schematics of sequential stages during endocytosis of the individual nanotube with surfactant coating. Only cross-section of the single nanotube is shown in the drawings.

To rule out the possibility of chemical environment change such as pH change as the main cause of the fluorescence intensity decrease, we immobilized SWCNTs with the same PEG coating on Au/Au surface without cells and adjusted the pH of the immersion medium from 5 to 9, with pH ~5 mimicking the acidic environment of endosomes and lysosomes42. A mere 15% decrease in fluorescence intensity was observed at pH ~5 (Supplementary Fig. S5), indicating the ~7-fold decay was mostly attributed to the z-axis displacement while the change of chemical environment had very little contribution.

In a control experiment, we depolarized the linearly polarized laser excitation to image and track a single nanotube endocytosis process and observed similar effect of fluorescence decrease over time with a 1/e decay time of 114 s at 37 °C (Supplementary Fig. S6). This suggested the observed fluorescence decay in the linear polarization case was due to reduced FE during endocytosis without large nanotube rotational effects. SWCNTs have been reported to rotate freely in water43. However, in our case, the nanotubes showed small rotations during endocytosis due to confinement and interactions with the membrane and the long 3 s integration time that had averaged out the rotational effects.

It is also possible that some nanotubes were bound to the cell membrane perpendicular to the Au–cell interface initially and endocytosed vertically as suggested recently for large multi-walled nanotubes44. The laser excitation used in our experiments was not able to excite and resolve these tubes efficiently. Also noticeable is that we had not observed a brightly fluorescent nanotube evolving into a dim state in a time scale of several seconds (the estimated rotation time if assuming free rotation in a viscous medium corresponding to the slow translational diffusivity measured), suggesting none of the SWCNTs imaged had changed orientation from in the x–y plane to pointing to the z-direction during endocytosis.

Given the control experiments ruling out other possibilities of fluorescence decay, the observed fluorescence decrease of the single nanotubes on the cells at 37 °C hinted axial motion of nanotubes away from the Au/Au substrate due to ultra-sensitive Au-SWCNT distance dependence of nanotube fluorescence intensity. On the basis of the nanoscopic ruler effect of FE, we rationalized that during 4 °C staining, RGD functionalized SWCNTs selectively attached to the αvβ3-integrin receptors on the cell membrane (Fig. 2f) without entering the cytoplasm due to blocked endocytosis at 4 °C (ref. 6). At 37 °C, endocytosis was activated with the formation of a vesicle wrapping around the surfactant-coated nanotube via clathrin-associated invagination of the plasma membrane (Fig. 2g), followed by vesicle pinching-off (Fig. 2h) and clathrin uncoating to undergo the endocytotic pathway45.

In the first ~20 s at 37 °C, the nanotube was sandwiched between the plasma membrane and the underlying Au/Au film (Fig. 2f), exhibiting high fluorescence due to close proximity to the fluorescence-enhancing surface (Fig. 2b). The distance from the membrane to substrate could reach 4–8 nm46 in less than 5 min47 according to the Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek model48. Over time (from Fig. 2b to 2c), clathrin assembled on the inner surface of the plasma membrane and the membrane bent inwards to form clathrin-coated pits and wrapped around the nanotube. Because of invagination, the nanotube was displaced away from the Au substrate (Fig. 2g), leading to reduced FE (Fig. 2c). At later times (from Fig. 2c to 2d), the clathrin-coated pit continued to grow and finally pinched off to form a complete vesicle enclosing the nanotube. At this point, the nanotube was >20 nm away from the Au substrate due to the two lipid bilayers in between (Fig. 2h). This large spatial separation led to very little enhancement from the plasmonic substrate (Fig. 2d). A complete sequence of such regulated events, including clathrin assembly, pits formation, budding and clathrin uncoating usually takes tens of seconds to a few minutes at 37 °C, depending on the size of the cargo molecule45. In case of this particular SWCNT, the time required to complete fluorescence decrease was ~250 s (Fig. 2e), within the reported time range to complete clathrin cluster assembly49, but on the higher side, similar to the time needed to internalize relatively large cargo molecules (~400 s) such as reovirus particles (~85 nm in diameter)45.

3D tracking of single nanotubes at various temperatures

To support that transmembrane motion of single nanotubes at 37 °C was indeed the cause of fluorescence decrease, we imaged single nanotubes on U87-MG cells at several other temperatures, including 4, 25 and 42 °C. It is known that at temperatures lower than 37 °C, cell functions such as active uptake are impaired, and endocytosis is completely blocked at 4 °C (ref. 6). On the other hand, cell functions are more active at elevated temperatures until excessive heating begins to cause damages50. In a typical experiment at 4 °C, we observed a single nanotube (evidenced by polarization dependence in Fig. 3a) moving on cell membrane (2D trajectory shown in Fig. 3b). This nanotube exhibited fluctuations in fluorescence intensity without any significant decay over sufficiently long periods of time (>900 s, see Fig. 3c and top left panel of Supplementary Movie 1). This was consistent with blocked endocytosis at this low temperature. The random fluctuations of fluorescence could be because of the stochastic fluctuations in the electrostatic environment of the cell medium (see Supplementary Fig. S7 for the degree of fluctuation even in the absence of cell)51, as well as small wiggles of SWCNT or subtle membrane motions that caused small Au-SWCNT distance fluctuations.

(a,d and g) Proof of single nanotubes being imaged through polarization-dependent fluorescence data. Error bars were obtained by taking the s.d. of the brightest and eight surrounding pixels that make up the single nanotube image. (b,e and h) show 2D trajectories of three different, individual SWCNTs on cell membranes at 4, 25 and 42 °C, respectively. (c,f and i) show the photoluminescence (PL) intensity (black squares) over time for the three individual nanotubes on cells at 4, 25 and 42 °C, respectively. At 25 and 42 °C, the data were fitted into a first-order exponential decay (red curve) with a 1/e decay time of 327 and 23 s, respectively.

At 25 °C, a temperature sufficiently high to initiate active cellular uptake but lower than 37 °C, we observed much longer time (1/e decay time=327 s) than at 37 °C (1/e decay time=100~120 s) to complete the transmembrane displacement of nanotubes (Fig. 3d–f and top right panel of Supplementary Movie 1). At 42 °C, a temperature known to enhance the endocytosis of mammalian cells52, the nanotube fluorescence intensity decreased so precipitously that the bright spot disappeared into the cells within only ~50 s (Fig. 3g–i and bottom right panel of Supplementary Movie 1). Once in the cells (Supplementary Fig. S8a–e) with little FE by the Au/Au substrate, the nanotube could be imaged after focusing the laser beam down to a much smaller area and thus, increasing the laser excitation power density by 20 times (Supplementary Fig. S8f).

Importantly, control experiments were performed at various temperatures (4–42 °C) on bare glass without any gold coating (Supplementary Fig. S9 and Supplementary Movie 2) for cells stained with SWCNTs. No fluorescence decrease of individual nanotubes was observed as on Au/Au plasmonic substrates at all temperatures up to long imaging and tracking times. This result again suggested that on the Au/Au plasmonic substrate, fluorescence intensity decrease of single tubes was due to reduced FE, as nanotubes were endocytosed into the cells away from the plasmonic substrate.

Single nanotube endocytosis activation barrier

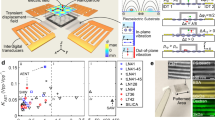

The imaging experiments on plasmonic Au/Au substrates at various temperatures were repeated with different single tubes (Supplementary Fig. S4) to obtain averaged 1/e decay times of individual nanotube fluorescence on cells (Fig. 4a). As endocytosis is a well-established energy-dependent process, from the 1/e decay times at different temperatures, we extracted an activation barrier for the internalization process to be 120±37 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 4b), which was significantly higher than the reported values for the clathrin-mediated endocytosis of some proteins (~55 kJ mol−1 for mannosylated albumin (~67 kDa) in trout hepatocytes53, and 40±13 kJ mol−1 for horseradish peroxidase (~44 kDa) in salmon-head kidney cells54]. The higher activation energy for cellular internalization of a single nanotube could be due to the large molecular weight (~1 MDa) or long tube length. To gain a quantitative view, we calculated the effective capture radius as follows15,

(a) A bar chart showing the average 1/e SWCNT fluorescence decrease (caused by transmembrane displacements during endocytosis) times at 25, 37 and 42 °C, corresponding to the averaged endocytosis times of SWCNTs at these temperatures. Error bars were obtained by taking the s.d. of three independent experiments at each temperature. (b) An Arrhenius plot for determining the activation energy of single nanotube transmembrane motion. Data points shown as black squares were fitted into a linear equation from which the activation barrier was extracted from the slope as ~120 kJ mol−1, and the error bars were obtained by taking the s.d. of three independent experiments at each temperature. (c) MSD curves versus lag time from four single nanotube tracking trajectories (Figs 2 and 3) at 4 °C (black solid curve), 25 °C (red solid curve), 37 °C (blue solid curve) and 42 °C (pink solid curve), respectively. All curves show a rather linear trend attributed to mostly Brownian motion and a small quadratic component at the beginning (fit to dashed curves in corresponding colours), whereas at 25, 37 and 42 °C, a second step showing abrupt rise from the linear trend was observed due to convective motion caused by active transport, corresponding to the completion of endocytosis of the single nanotubes. (d) A bar chart showing at different temperatures the change of convective diffusion velocity before (red bars) and after (blue bars) the endocytotic completion point based on the abrupt MSD upturn point. The error bars were obtained by taking the s.d. of three independent experiments at each temperature.

where the average length of our SWCNTs was 2a=1 μm, and they were coated with long PEG chains with an overall radius of b~7.5 nm. The as-calculated effective radius lied in the vesicle wrapping region for nanoparticles, but was on the high side, as suggested by the model of Gao et al.16 An optimum size for the cellular entry of both Au nanoparticles and SWCNTs has been reported15,55 to be ~25 nm in effective radius, smaller than the effective radius of the SWCNTs used in the current work. Therefore, although endocytosis mediated by membrane wrapping was more favourable than direct insertion in our case, the large effective capture radius slowed down this process with a relatively high apparent activation barrier.

MSD analysis of 2D trajectories

To verify the fluorescence intensity decrease in each case indeed reflected the process of endocytosis, we also carried out the mean square displacement (MSD) analysis, based on the 2D nanotube trajectories in the x–y plane. MSD was plotted in Fig. 4c as a function of lag time for each of the four single nanotube trajectories at different temperatures in Figs 2 and 3. For nanotube trajectories recorded at three elevated temperatures 25, 37 and 42 °C, the MSD curves all exhibited nearly linear increase initially with a small quadratic component regressed as the dashed curves. This indicated dominant Brownian motion during the vesicle formation process56. Diffusivity values extracted from the curves were in a range between 103 to 104 nm2 s−1, consistent with the diffusion constant of membrane receptors on the order of 104 nm2 s−1 (ref. 57 and suggesting nanotubes bound to membrane receptors during the initial stage of motion. The measured translational diffusivity range was two to three orders of magnitude smaller than in water (>1 μm2 s−1)43, suggesting strong interactions between nanotubes and cell membranes that hindered the diffusion or rotation of SWCNTs during endocytosis.

Interestingly, after sufficiently long period of time depending on the temperature, a turning point showed up in each of these three cases (940 s at 25 °C, 260 s at 37 °C and 50 s at 42 °C), after which a dramatic increase in MSD was observed. The MSD was fit to a quadratic function with reduced Brownian component, indicating the completion of vesicle formation and an active transport of the encapsulated cargo7. In contrast, when tracking a single nanotube at 4 °C, the MSD curve kept increasing almost linearly without an abrupt upward turning point (Fig. 4c). These results are in agreement with other studies7, where convective diffusion is usually observed after a single nanoparticle has been fully endocytosed due to microtubule-dependent transport by motor proteins58. Figure 4d revealed a large increase in convective motion velocity immediately following endocytosis. Moreover, as the turning point indicated when the complete vesicle was formed and motor proteins started transporting the cargo vesicle, we compared the turning point in each MSD curve with the time required for the starting fluorescence intensity to drop to baseline level from Figs 2 and 3, which acted as another measure of the endocytosis completion time. Strikingly, results from these two methods matched very well. At 25 °C, the turning point was at 940 s, whereas endocytosis completion was at ~880 s according to fluorescence intensity decrease. At 37 °C, the turning point was at 260 s, whereas the fluorescence decay curve showed complete endocytosis at ~250 s. At 42 °C, the time of turning point was 50 s, whereas from the fluorescence decay, the time of complete endocytosis was ~60 s. MSD analyses for all other trajectories of SWCNTs were also carried out and shown in Supplementary Fig. S10. We reproducibly observed two distinct steps for the imaged SWCNTs, an initial stage of dominant Brownian motion, and subsequent convective diffusion with abrupt increase in MSD. Thus, the MSD analysis confirmed the occurrence of endocytosis, and the turning points from the MSD curves further verified our intensity-based measurement as a way to follow the endocytosis process.

Block of endocytosis

Previous work has found that cellular internalization of ensembles of CNTs involves the clathrin-dependent endocytosis pathway6. Potassium depletion, as well as hypertonic medium incubation, are the two methods known to perturb endocytosis by removing membrane-associated clathrin lattice59. To glean if transmembrane endocytosis of individual SWCNTs observed with the plasmonic 'ruler' did involve the formation of clathrin lattice on the plasma membrane, we investigated the effects of potassium depletion and hypertonic treatment to the internalization of single nanotube molecules. In a hypertonic treatment, we pre-incubated U87-MG cells with sucrose-supplemented buffer at 37 °C and then stained the cells at 4 °C. After the temperature of imaging chamber was raised to 37 °C, a bright individual nanotube was found to move around (Fig. 5a and left panel of Supplementary Movie 3) in 2D without fluorescence decrease over a long period of time (>1,000 s, Fig. 5b). This result suggested blocking of endocytosis of single nanotubes by hypertonic treatment at 37 °C. Similar result was observed after treating cells in potassium-depleted medium (Fig. 5c,d and right panel of Supplementary Movie 3), also confirming blocking of endocytosis by depleting K+ ions from the medium. It has been shown that both hypertonic incubation and potassium depletion induce abnormal clathrin polymerization into empty microcages59 (Fig. 5e), preventing interactions between clathrin and its adaptor AP-2, and thus blocking the formation of clathrin-coated pits that are essential to receptor-mediated endocytosis.

(a,c) 2D trajectories of two independent SWCNTs observed on cells pre-treated by sucrose and potassium depletion, respectively. (b) and (d) show the time-course photoluminescence (PL) of the two individual SWCNTs on the sucrose-treated and potassium-depletion-treated cells, respectively, at 37 °C. (e) A schematic drawing showing the lack of clathrin lattice formation on the cell membrane under either hypertonic or potassium-depleted condition, which blocks the formation of clathrin-coated pits (as in Fig. 2g,h) and receptor-mediated endocytosis of the SWCNT.

Discussion

This work exploited the sensitive distance dependence of NIR-FE of single CNT molecules on a gold plasmonic substrate to probe ~10 nm scale transmembrane displacements through changes in nanotube fluorescence intensity, presented the first 3D tracking of individual SWCNTs, and established the nanotube entry pathway to be clathrin-dependent endocytosis. Compared with other existing 3D single-particle imaging and tracking techniques that either require sophisticated implementation or are limited with insufficient axial and/or temporal resolution18, the sensitive distance dependence of FE based on the plasmonic effect presents a facile, inexpensive and sensitive probing of sub-10-nm distance changes in biological systems. Notably, spatial sensitivity and range of distance measurements are difficult to optimize simultaneously. Our current method allows for probing subtle distance changes of <10 nm along the z-axis, but tracking displacements beyond ~20 nm becomes difficult because of the short plasmonic ruler length. It is necessary to resort to other fluorophores with different plasmonic ruler lengths, such as synthetic dyes, fluorescent nanoparticles or fluorescent proteins to extend the measurable range along the z-axis. Our preliminary results have indeed identified that the plasmonic FE versus the distance profile is characteristic to each fluorophore and also depends on the type of plasmonic substrates. Suitable combinations of fluorophore-substrate could lead to a library of 'nanoscopic rulers' spanning various ranges of distances to probe molecular motions at the nanoscale.

We envisage that the reverse process of endocytosis, exocytosis7,60 of single nanotubes or molecules could also be investigated by utilizing FE phenomena on plasmonic substrates. Further, similar to transmembrane processes, imaging with suitable plasmonic rulers may also offer a platform to decipher important biological pathways involving translocational motions of molecules inside cells. Distance information and protein conformational changes inside the cytoplasm could also be revealed by introducing plasmonic metal nanoparticles and fluorophores inside live cells.

Methods

Preparation of Au/Au films

The solution-phase Au/Au film synthesis can be found in detail in another publication of our group26. Briefly, a glass slide was immersed in a 25 ml solution of 3 mM chloroauric acid, to which 400 μl of ammonia was added under vigorous agitation. The substrate was then allowed to sit in the seeding solution with gentle shaking for 1 min, after which it was rinsed with water. Then, the substrate was submerged into a 25 ml solution of 1 mM sodium borohydride on an orbital shaker at 100 r.p.m. for 5 min. Following a second rinsing step, the seeded substrate was soaked in a 25 ml solution of 1 mM chloroauric acid and 1 mM hydroxylamine under agitation for 15 minutes. It was then rinsed with water and soaked in 1 mM cysteamine ethanol solution for 1 h to render it hydrophilic and biocompatible.

Ultraviolet-Vis-NIR absorbance measurements

Ultraviolet-Vis-NIR absorbance curve of the as-made Au/Au film on glass substrate was measured by a Cary 6000i UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer, background-corrected for any glass contribution. The measured range was 400–1,200 nm.

SEM imaging

Au/Au film grown on glass was imaged via SEM. Image was acquired on an FEI XL30 Sirion SEM with FEG source at 5 kV acceleration voltage.

ALD process

Low-temperature ALD process was used to coat the as-made Au/Au film with desirable thicknesses. Deposition was carried out on amine group-functionalized hydrophilic Au/Au substrate at 100 °C in ~300 mTorr pure nitrogen environment, where trimethylaluminum and water vapour were used as precursors. For each cycle of ALD, water pulse was 0.5 s in duration, followed by a 40 s purging time, a 0.5 s trimethylaluminum pulse and a 30 s purging time. To deposit the Al2O3 layers of 5, 10, 15 and 20 nm, 50, 100, 150 and 200 cycles were used, respectively.

Preparation of water-soluble SWCNT–PEG–RGD bioconjugate

The preparation of water-soluble SWCNT fluorophores can be found in detail in another publication of our group with some modification34. In general, raw HiPCO SWCNTs (Unidym) were suspended in 1 wt% sodium deoxycholate aqueous solution by 1 h of bath sonication. This suspension was ultracentrifuged at 300,000 g to remove the bundles and other large aggregates. To further remove any remaining bundles and keep only bright single nanotubes, a gradient separation was used to purify the as-made SWCNTs. The supernatant was first concentrated and then layered to the top of a 10/20/30/40 wt% sucrose step gradient, followed by ultracentrifugation at 300,000 g for 1 h. Only the top, 1 ml was retained by careful fractionation and 0.75 mg ml−1 of C18-PMH-mPEG (5 kDa for each PEG chain, 90 kDa in total; MW=90,000 in total), synthesized by our group) along with 0.25 mg ml−1 of DSPE-PEG (5 kDa)-NH2 (Laysan Bio) was added. The resulting suspension was sonicated briefly for 5 min and then dialysed at pH 7.4 in a 3,500 Da membrane (Fisher) with a minimum of six water changes and a minimum of 2 h between water changes. To remove aggregates, the suspension was ultracentrifuged again for 1 h at 300,000 g. This surfactant-exchanged SWCNT sample has lengths ranging from 100 nm up to 3.0 μm, with the average length of ~1 μm as shown in Supplementary Figure S1. These amino-functionalized SWCNTs were further conjugated with RGD peptide according to the protocol that has been used in our group. Briefly, an SWCNT solution with amine functionality at 300 nM after removal of excess surfactant, was mixed with 1 mM sulfo-SMCC (sulfosuccinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate) at pH 7.4 for 2 h in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4. After removing excess sulfo-SMCC by filtration through 100-kDa filters (Amicon), RGD-SH (cyclo-RGDFC, Peptides International) was added together with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) at pH 7.4. The final concentrations of SWCNT, RGD-SH and TCEP were 300 nM, 0.1 and 1 mM, respectively. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 2 days at 4 °C before purification to remove excess RGD and TCEP by filtration through 100-kDa filters.

AFM imaging

AFM image of the as-made SWCNT conjugate was acquired with a Nanoscope IIIa multimode instrument in the tapping mode. The sample for imaging was a drop-dried sample on glass, the same one for calibration curve measurement of the distance dependence of FE, prepared by drop-drying 0.5 μl water-soluble PEGylated and functionalized SWCNTs (0.45 nM) solution containing 0.05 wt% Triton X-100 on a bare glass substrate and calcination at 350 °C for 15 min.

Calibration curve of distance-dependent FE

To determine the calibration curve, on the bare glass substrate and each Au/Au substrate with a certain thickness of Al2O3 coating, 0.5 μl water-soluble, PEGylated and functionalized SWCNTs (0.45 nM) solution containing 0.05 wt% Triton X-100 was drop-dried to form a uniform spot with diameter of ~2 mm. All spots were imaged in epifluorescence setup with a 658 nm laser diode (100 mW, Hitachi) focused to a 750 μm diameter spot by focusing the laser near the back focal length of a ×10 objective lens (Bausch & Lomb). The resulting NIR PL was collected using a liquid-nitrogen-cooled, 320×256 pixel, 2D InGaAs camera (Princeton Instruments) with a sensitivity ranging from 800 to 1700 nm. The excitation light was filtered out using an 1,100 nm long-pass filter (Omega) so that the intensity of each pixel represented light in the 1,100–1,700 nm range. The exposure time was 100 ms. Images were taken in a 2D scanning mode, flat-field-corrected to account for non-uniform laser excitation, and then stitched automatically using LabVIEW to recover the original shape of the spot. Integral intensity for each stitched spot was done using the roipolyarray function in MATLAB software.

Cell incubation and staining

The U87-MG cell medium containing 1 g l−1 D-glucose, 110 mg l−1 sodium pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin and L-glutamine was used. Cells were maintained in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2. To stain cells with SWCNT–PEG–RGD, trypsinized U87-MG cells were mixed with SWCNT–PEG–RGD at a nanotube concentration of 1 nM (for imaging on glass; this higher concentration helped to find the brighter single nanotubes from a distribution including many dim tubes) or 20 pM (for imaging on Au/Au, which helped to visualize the otherwise dim tubes by enhancement) at 4 °C for 1 h, followed by washing the cells with 1× PBS to remove all free conjugates in the suspension. For the hypertonic treatment, the original cell medium was completely removed and the cells were incubated in 1× PBS supplemented with 0.45 M sucrose at 37 °C for 0.5 h before trypsinized and stained. For the potassium depletion treatment, the original cell medium was removed and the cells were incubated in a potassium-free buffer containing 0.1 M HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid), 1.4 M NaCl and 25 mM CaCl2 at 37 °C for 0.5 h before trypsinized and stained. Note that for the K+-depletion treatment, the potassium-free buffer was used to replace 1× PBS wherever 1× PBS was needed throughout the entire procedure.

High-magnification NIR PL imaging

A volume of 5 μl of stained U87-MG cell suspension was transferred to 200 μl of 1× PBS or potassium-free buffer (for potassium depletion treatment), placed into an eight-well chamber slide (Lab-Tek Chambered Coverglass, 1.0 Borosilicate). An Au/Au-coated glass substrate or a bare glass chip was then placed on top. Capillary force formed a very thin layer of liquid between the substrate and coverglass, allowing a monolayer of cells residing in between. The chamber slide was kept in a temperature-controlled chamber (BC-260W, 20/20 Technology, Inc.) for epifluorescence imaging. Temperature was always kept at 4 °C at the beginning for at least 5 min to ensure the cell membrane in close contact with the hydrophilic gold surface. The temperature of the imaging cell was controlled by heat exchanger (HEC-400, 20/20 Technology, Inc.), and the CO2 gas flow was kept at 1 l min−1 by a gas purging system (GP-502, 20/20 Technology, Inc.). Single-nanotube imaging and tracking were done using a 658-nm laser diode excitation with an 80 μm diameter spot focused by a ×100 objective lens (Olympus). The resulting NIR PL was collected using a liquid-nitrogen-cooled, 320×256 pixel, 2D InGaAs camera (Princeton Instruments) with a sensitivity ranging from 800 to 1,700 nm. The excitation light was filtered out using a 1,100 nm long-pass filter (Thorlabs) so that the intensity of each pixel represented light in the 1,100–1,700 nm range. To initiate the active uptake of single nanotubes, the chamber temperature was increased from the initial temperature of 4 °C and stabilized at the set temperature (usually took 2 min). The camera took images to record endocytotic process continuously with an exposure time of 3 s. Matlab 7 was used to process the images for any necessary flat-field correction and extract trajectories and time courses of PL changes from the video.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Hong, G. et al. Three-dimensional imaging of single nanotube molecule endocytosis on plasmonic substrates. Nat. Commun. 3:700 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1698 (2012).

References

Zhao, Y. & Nalwa, H. S. Nanotoxicology: Interactions of Nanomaterials with Biological Systems (American Scientific Publishers, 2007).

Rouse, J. G., Yang, J. Z., Barron, A. R. & Monteiro-Riviere, N. A. Fullerene-based amino acid nanoparticle interactions with human epidermal keratinocytes. Toxicol. In Vitro 20, 1313–1320 (2006).

Osaki, F., Kanamori, T., Sando, S., Sera, T. & Aoyama, Y. A quantum dot conjugated sugar ball and its cellular uptake on the size effects of endocytosis in the subviral region. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 6520–6521 (2004).

Zhang, Y., Kohler, N. & Zhang, M. Q. Surface modification of superparamagnetic magnetite nanoparticles and their intracellular uptake. Biomaterials 23, 1553–1561 (2002).

Pantarotto, D., Briand, J. P., Bianco, A. & Prato, M. Translocation of bioactive peptides across cell membranes by carbon nanotubes. Chem. Commun. 16–17 (2004).

Kam, N. W. S., Liu, Z. A. & Dai, H. J. Carbon nanotubes as intracellular transporters for proteins and DNA: an investigation of the uptake mechanism and pathway. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 577–581 (2006).

Jin, H., Heller, D. A. & Strano, M. S. Single-particle tracking of endocytosis and exocytosis of single-walled carbon nanotubes in NIH-3T3 cells. Nano Lett. 8, 1577–1585 (2008).

Lu, Q. et al. RNA polymer translocation with single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 4, 2473–2477 (2004).

Bianco, A. et al. Cationic carbon nanotubes bind to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and enhance their immunostimulatory properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 58–59 (2005).

Lopez, C. F., Nielsen, S. O., Moore, P. B. & Klein, M. L. Understanding nature's design for a nanosyringe. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 4431–4434 (2004).

Kam, N. W. S., O'Connell, M., Wisdom, J. A. & Dai, H. J. Carbon nanotubes as multifunctional biological transporters and near-infrared agents for selective cancer cell destruction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11600–11605 (2005).

Cherukuri, P., Bachilo, S. M., Litovsky, S. H. & Weisman, R. B. Near-infrared fluorescence microscopy of single-walled carbon nanotubes in phagocytic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 15638–15639 (2004).

Liu, Y. et al. Polyethylenimine-grafted multiwalled carbon nanotubes for secure noncovalent immobilization and efficient delivery of DNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 4782–4785 (2005).

Heller, D. A., Baik, S., Eurell, T. E. & Strano, M. S. Single-walled carbon nanotube spectroscopy in live cells: Towards long-term labels and optical sensors. Adv. Mater. 17, 2793–2799 (2005).

Jin, H., Heller, D. A., Sharma, R. & Strano, M. S. Size-dependent cellular uptake and expulsion of single-walled carbon nanotubes: single particle tracking and a generic uptake model for nanoparticles. ACS Nano 3, 149–158 (2009).

Gao, H. J., Shi, W. D. & Freund, L. B. Mechanics of receptor-mediated endocytosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 9469–9474 (2005).

Jaiswal, J. K. & Simon, S. M. Imaging single events at the cell membrane. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 92–98 (2007).

Dupont, A. & Lamb, D. C. Nanoscale three-dimensional single particle tracking. Nanoscale 3, 4532–4541 (2011).

Axelrod, D., Burghardt, T. P. & Thompson, N. L. Total internal-reflection fluorescence. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bio. 13, 247–268 (1984).

Bates, M., Huang, B. & Zhuang, X. W. Super-resolution microscopy by nanoscale localization of photo-switchable fluorescent probes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 12, 505–514 (2008).

Huang, B., Jones, S. A., Brandenburg, B. & Zhuang, X. W. Whole-cell 3D STORM reveals interactions between cellular structures with nanometer-scale resolution. Nat. Methods 5, 1047–1052 (2008).

Pavani, S. R. P. et al. Three-dimensional, single-molecule fluorescence imaging beyond the diffraction limit by using a double-helix point spread function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2995–2999 (2009).

Wildanger, D., Medda, R., Kastrup, L. & Hell, S. W. A compact STED microscope providing 3D nanoscale resolution. J. Microsc. -Oxford 236, 35–43 (2009).

Cang, H., Xu, C. S. & Yang, H. Progress in single-molecule tracking spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 457, 285–291 (2008).

Hong, G. S. et al. Metal-enhanced fluorescence of carbon nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 15920–15923 (2010).

Tabakman, S. M., Chen, Z., Casalongue, H. S., Wang, H. L. & Dai, H. J. A New approach to solution-phase gold seeding for SERS substrates. Small 7, 499–505 (2011).

Hong, G. S. et al. Near-infrared-fluorescence-enhanced molecular imaging of live cells on gold substrates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 4644–4648 (2011).

Tabakman, S. M. et al. Plasmonic substrates for multiplexed protein microarrays with femtomolar sensitivity and broad dynamic range. Nat. Comm. 2, 466 (2011).

Liu, Z., Tabakman, S., Welsher, K. & Dai, H. J. Carbon nanotubes in biology and medicine: in vitro and in vivo detection, imaging and drug delivery. Nano Res. 2, 85–120 (2009).

Bachilo, S. M. et al. Structure-assigned optical spectra of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Science 298, 2361–2366 (2002).

O'Connell, M. J. et al. Band gap fluorescence from individual single-walled carbon nanotubes. Science 297, 593–596 (2002).

Welsher, K., Liu, Z., Daranciang, D. & Dai, H. Selective probing and imaging of cells with single walled carbon nanotubes as near-infrared fluorescent molecules. Nano Lett. 8, 586–590 (2008).

Welsher, K. et al. A route to brightly fluorescent carbon nanotubes for near-infrared imaging in mice. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 773–780 (2009).

Tabakman, S. M., Welsher, K., Hong, G. S. & Dai, H. J. Optical properties of single-walled carbon nanotubes separated in a density gradient: length, bundling, and aromatic stacking effects. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 19569–19575 (2010).

Welsher, K., Sherlock, S. P. & Dai, H. J. Deep-tissue anatomical imaging of mice using carbon nanotube fluorophores in the second near-infrared window. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 8943–8948 (2011).

Liu, Z. et al. Multiplexed five-color molecular imaging of cancer cells and tumor tissues with carbon nanotube Raman tags in the near-infrared. Nano Res. 3, 222–233 (2010).

Robinson, J. T. et al. High performance in vivo near-IR (> 1 μm) imaging and photothermal cancer therapy with carbon nanotubes. Nano Res. 3, 779–793 (2010).

Liu, Z. et al. In vivo biodistribution and highly efficient tumour targeting of carbon nanotubes in mice. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 47–52 (2007).

Bae, S. C., Xie, F., Jeon, S. & Granick, S. Single isolated macromolecules at surfaces. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mat. Sci. 5, 327–332 (2001).

Lakowicz, J. R. Plasmonics in biology and plasmon-controlled fluorescence. Plasmonics 1, 5–33 (2006).

Tsyboulski, D. A., Bachilo, S. M. & Weisman, R. B. Versatile visualization of individual single-walled carbon nanotubes with near-infrared fluorescence microscopy. Nano Lett. 5, 975–979 (2005).

Mellman, I., Fuchs, R. & Helenius, A. Acidification of the endocytic and exocytic pathways. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 55, 663–700 (1986).

Tsyboulski, D. A., Bachilo, S. M., Kolomeisky, A. B. & Weisman, R. B. Translational and rotational dynamics of individual single-walled carbon nanotubes in aqueous suspension. ACS Nano 2, 1770–1776 (2008).

Shi, X., von dem Bussche, A., Hurt, R. H., Kane, A. B. & Gao, H. Cell entry of one-dimensional nanomaterials occurs by tip recognition and rotation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 714–719 (2011).

Ehrlich, M. et al. Endocytosis by random initiation and stabilization of clathrin-coated pits. Cell 118, 591–605 (2004).

Weiss, L. & Harlos, J. P. Some speculations on the rate of adhesion of cells to coverslips. J. Theor. Biol. 37, 169–179 (1972).

Vogler, E. A. & Bussian, R. W. Short-term cell-attachment rates: a surface-sensitive test of cell-substrate compatibility. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 21, 1197–1211 (1987).

Ratner, B. D., Hoffman, A. S., Schoen, F. J. & Lemons, J. E. Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine 142–144 (Academic Press, 1996).

Kirchhausen, T., Boll, W., van Oijen, A. & Ehrlich, M. Single-molecule live-cell imaging of clathrin-based endocytosis. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 72, 71–76 (2005).

Goldenthal, K. L., Pastan, I. & Willingham, M. C. Initial steps in receptor-mediated endocytosis: the influence of temperature on the shape and distribution of plasma membrane clathrin-coated pits in cultured mammalian cells. Exp. Cell. Res. 152, 558–564 (1984).

Ai, N., Walden-Newman, W., Song, Q., Kalliakos, S. & Strauf, S. Suppression of blinking and enhanced exciton emission from individual carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano 5, 2664–2670 (2011).

Hahn, G. M., Braun, J. & Harkedar, I. Thermochemotherapy: synergism between hyperthermia (42–43 degrees) and Adriamycin (or Bleomycin) in Mammalian-cell inactivation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 72, 937–940 (1975).

Rosjo, C. et al. Effects of temperature and dietary N-3 and N-6 fatty acids on endocytic processes in isolated rainbow-trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss, Walbaum) hepatocytes. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 13, 119–132 (1994).

Rode, M., Berg, T. & Gjoen, T. Effect of temperature on endocytosis and intracellular transport in the cell line SHK-1 derived from salmon head kidney. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A 117, 531–537 (1997).

Chithrani, B. D., Ghazani, A. A. & Chan, W. C. W. Determining the size and shape dependence of gold nanoparticle uptake into mammalian cells. Nano Lett. 6, 662–668 (2006).

Gaidarov, I., Santini, F., Warren, R. A. & Keen, J. H. Spatial control of coated-pit dynamics in living cells. Nat. Cell. Biol. 1, 1–7 (1999).

Bell, G. I. Models for specific adhesion of cells to cells. Science 200, 618–627 (1978).

Courty, S., Luccardini, C., Bellaiche, Y., Cappello, G. & Dahan, M. Tracking individual kinesin motors in living cells using single quantum-dot imaging. Nano Lett. 6, 1491–1495 (2006).

Hansen, S. H., Sandvig, K. & Vandeurs, B. Clathrin and Ha2 adapters—effects of potassium-depletion, hypertonic medium, and cytosol acidification. J. Cell Biol. 121, 61–72 (1993).

Zhang, Q., Li, Y. L. & Tsien, R. W. The dynamic control of kiss-and-run and vesicular reuse probed with single nanoparticles. Science 323, 1448–1453 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH-NCI 5R01CA135109-02 and Stanford Graduate Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. D. and G. H. conceived and designed the experiments. G. H., J. Z. W., J. T. R., H. W. and B. Z. performed the experiments. G. H. and H. D. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Movie 1

Imaging of Single Carbon Nanotubes on Cells Cast on Gold Plasmonic Substrates at 4 °C, 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. U87-MG glioblastoma cells were stained with single-walled carbon nanotube suspension at 20 pM concentration at 4 °C and cast onto gold plasmonic substrates. Single carbon nanotubes were identified and imaged over time as the incubation temperature was changed to 4 °C, 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. (AVI 8377 kb)

Supplementary Movie 2

Imaging of Single Carbon Nanotubes on Cells Cast on Glass Substrates at 4 °C, 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. U87-MG glioblastoma cells were stained with singlewalled carbon nanotube suspension at 1 nM concentration at 4 °C and cast onto glass substrates. Single carbon nanotubes were identified and imaged over time as the incubation temperature was changed to 4 °C, 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. (AVI 8047 kb)

Supplementary Movie 3

Imaging of Single Carbon Nanotubes on Cells Cast on Gold Plasmonic Substrates at 37 °C under hypertonic and potassium depletion treatments. U87-MG glioblastoma cells were stained with single-walled carbon nanotube suspension at 20 nM concentration at 4 °C, cast onto gold plasmonic substrates and incubated in high concentration sucrose hypertonic medium (left) or potassium depleted medium (right). Single carbon nanotubes were identified and imaged over time as the incubation temperature was changed to 37 °C. (AVI 7613 kb)

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S10, Supplementary References (PDF 1012 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, G., Wu, J., Robinson, J. et al. Three-dimensional imaging of single nanotube molecule endocytosis on plasmonic substrates. Nat Commun 3, 700 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1698

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1698

This article is cited by

-

Detonation Nanodiamonds as Promising Drug Carriers

Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal (2020)

-

NIR-II probe modified by poly(L-lysine) with efficient ovalbumin delivery for dendritic cell tracking

Science China Chemistry (2020)

-

Advances in nanomaterials for brain microscopy

Nano Research (2018)

-

Discovery of a Biological Mechanism of Active Transport through the Tympanic Membrane to the Middle Ear

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Biological imaging without autofluorescence in the second near-infrared region

Nano Research (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.