Abstract

Stable benzotriazinyl radicals (Blatter’s radicals) recently attracted considerable interest as building blocks for functional materials. The existing strategies to derivatize Blatter’s radicals are limited, however, and synthetic routes are complex. Here, we report that an inexpensive, commercially available, analytical reagent Nitron undergoes a previously unrecognized transformation in wet acetonitrile in the presence of air to yield a new Blatter-type radical with an amide group replacing a phenyl at the C(3)-position. This one-pot reaction of Nitron provides access to a range of previously inaccessible triazinyl radicals with excellent benchtop stabilities. Mechanistic investigation suggests that the reaction starts with a hydrolytic cleavage of the triazole ring followed by oxidative cyclization. Several derivatives of Nitron were prepared and converted into Blatter-type radicals to test the synthetic value of the new reaction. These results significantly expand the scope of using functionalized benzotriazinyls as stable radical building blocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

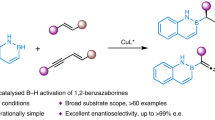

Blatter’s radical 1 (Fig. 1)1 is an example of a benzotriazinyl radical with remarkable bench-top stability. Although relatively unexplored since the early report by Blatter in 1968, there has been increased recent interest in this radical and derivatives due to their suitability as building blocks for magnetic materials2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, as polymerization initiators14,15,16 and as ligands in novel radical-metal coordination complexes17,18. Related benzotriazines and N-oxide derivatives have seen application in medicinal chemistry, including as anti-cancer drugs, where benzotriazinyl radicals have been proposed as potential DNA-damaging species19,20,21,22. All reported Blatter-type radicals to date limit C(3)-substitution to (hetero)aryl, alkenyl or alkyl groups.

Here, we report the mechanism and initial scope of an unexpected reaction of Nitron 2 (a low cost, common analytical reagent) to give a new kind of Blatter-type radical with an amide replacing a phenyl at the 3-position (Fig. 1). Nitron 2 has been used for gravimetric and spectrophotometric determination of nitrate and perchlorate ions for over 100 years23, and is usually assigned a zwitterionic Lewis structure 2. In 2012, Färber et al.24 provided evidence that Nitron exhibits some reactivity more consistent with N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) tautomer 2′, which had not been previously considered. Although the levels of NHC tautomer were too small to be detectable by NMR, Nitron 2 reacted with typical trapping reagents for nucleophilic carbenes including elemental sulfur and CS2.

Results

Transformation of Nitron 2 to Blatter-type radical 3

During the course of our studies we found that Nitron 2 undergoes an unprecedented one-pot conversion into amido Blatter radical 3 which can subsequently be hydrolysed to yield an amine-functionalized radical 4, thus providing useful structural handles to enable modification of the properties for functional materials and other applications (Fig. 2). Our initial aims were to investigate the proton transfer properties of Nitron 2 compared with related 1,2,4-triazolium ions to further explore the significance of the 2–2′ tautomerization. We have recently studied the proton transfer reactions of a broad range of triazolium salt precursors of triazolyl NHCs structurally very similar to the NHC tautomer of Nitron 2′, albeit with alkyl or aryl rather than an anilino-substituent25,26. In a similar study of the proton transfer properties of Nitron, it was noted that the colour of stock solutions of Nitron 2 in acetonitrile changed from translucent orange to opaque brown over 24 h. By contrast, analogous acetonitrile solutions of all other triazolium ions that we have studied to date remained unchanged over several weeks. Black crystals were observed to form upon concentration of the stock acetonitrile solution of Nitron 2, and after isolation and purification, the unusual decomposition product 3 was isolated in 58% yield. Radical 3 proved to be stable in air and at room temperature for months, and its structure was determined using X-ray crystallography (Fig. 3a).

(a) X-ray crystal structure of 3 showing two orientations of the phenyl group in the solid state and weak hydrogen bonds in the stack of molecules. (b) EPR spectrum of 3 in dioxane at 343 K. (c) SOMO in 3 with contours plotted at ±0.07 (e/bohr3)1/2. (d) Spin density distribution in 3 with contours plotted at ±0.008 (e/bohr3)1/2.

The structure of amido radical 3 (Fig. 3a) contains two crystallographically independent molecules with different orientation of Ph-substituents at N1. Molecules of 3 stack along the a-direction (Supplementary Fig. 1) and this slipped-stacked packing motif has been found in the other known crystal structures of Blatter-type radicals27. Two independent molecules alternate in the stack with corresponding interplanar distances between the r.m.s. planes of benzotriazines of 3.68 and 3.61 Å (Supplementary Fig. 2). The shortest C…N and C…C interatomic contacts between planes are equal to 3.62 and 3.53 Å (Fig. 3a), similar to those reported for other benzotriazinyl radicals (3.3–3.8 Å). Additional C–H…O and C–H…π contacts link the stacks together into a 3D-framework. Manipulation of weak hydrogen bonding interactions, as observed in 3 (Fig. 3a), may provide a means for controlling bulk magnetic behaviour28,29.

EPR studies of 3 revealed hyperfine coupling constants (hfccs) similar to those reported for related Blatter radicals and peak intensities consistent with pure radical character. The solution EPR spectrum of 3 (Fig. 3b) exhibits nine lines consistent with the coupling of the unpaired electron with the three ring triazinyl nitrogens. The largest hfcc can be assigned to N(1) (8.14 G) with the next largest (5.01 G, 4.69 G) to N(2) and N(4), respectively (Supplementary Tables 1–3). The SOMO and spin distributions of 3 determined by computations show the free radical to largely reside at the nitrogens of the triazine ring (N1, N2 and N4) (Fig. 3c,d, Supplementary Fig. 3), and the data are in accord with reported calculated data for related radical species3,6. The hfcc for the fourth exo-cyclic nitrogen is unresolved. The redox behaviour of radical 3 is typical of 1,2,4-benzotriazinyls showing two fully reversible waves that correspond to −1/0 and 0/+1 processes (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 4).

Synthesis of amino-substituted Blatter-type radical 4

As well as amide radical 3, we isolated trace amounts of green amino radical 4 (Fig. 2) upon column purification of the stock solution of Nitron 2 in acetonitrile. Subsequently, it was shown that 4 can be prepared from 3 in 70% yield by hydrolysis in concentrated sodium hydroxide solution. The structure of radical 4, which lacks a formyl group on the C(3)-nitrogen substituent, was confirmed by X-ray crystallography (Supplementary Fig. 5), EPR (Supplementary Fig. 6), cyclic voltammetry (Supplementary Fig. 7) and other techniques. The SOMO and spin distribution of radical 4 are similar to that of 1 and 3 (Supplementary Fig. 8). Our observation of the clean conversion of radical 3 to 4, albeit under strongly basic conditions, suggests that the formation of 4 during the reaction of Nitron 2 in acetonitrile is due to hydrolysis of 3. To our knowledge, this is also the first report of a C(3)-amino substituted Blatter radical 4, which could be a useful and versatile building block for the preparation of other related radicals.

Reaction mechanism and optimization of reaction conditions

A potential mechanism for the formation of radical 3 from Nitron 2 is proposed in Fig. 4. This mechanism relies upon initial partial hydrolysis by adventitious water in acetonitrile. Attack of water at the carbenoid centre of Nitron 2 followed by subsequent ring-opening would yield amido-substituted amidrazone (Z)-5, which can easily isomerize to (E)-5. In the case of Nitron 2, the presence of tautomer 2′ could favour the initial hydration step that precedes ring-opening. Amidrazones such as (E)-5 are also intermediates in the conventional synthetic route to Blatter-type radicals from imidoyl or hydrazonyl chlorides2,3,6,30,31,32. Similar to the literature-proposed mechanism30,31,32, conversion of (E)-5 to 3 could thus involve the initial in situ formation of 1,2,4-triazabutadienes 6, followed by electrocyclic ring closure to benzotriazines and further oxidation. Alternatively, the amidrazone could undergo one-electron oxidation to a hydrazonyl radical 7 followed by ring closure to a benzotriazine and further oxidation (Fig. 4).

The first step involves initial hydrolytic ring-opening of Nitron 2 to amidrazones 5. Two electron oxidation of 5 to C(3)-amidotriazabutadiene 6 and subsequent oxidative electrocyclization would yield C(3)-amido Blatter radical 3. Alternatively the one electron oxidation of 5 to hydrazonyl radical 7 followed by addition to the adjacent benzene ring and further oxidation would also yield 3.

The proposed mechanism for the conversion of Nitron 2 into radical 3 was clarified in a range of experiments. No EPR signal could be obtained when a solution of Nitron 2 in dry acetonitrile was exposed to UV light for 4 h or when stirred under an oxygen atmosphere for 3 days. By contrast, an EPR signal could be detected after addition of 2% v/v water to the acetonitrile solution confirming the requirement for low levels of water. Triazabutadiene 8 (Fig. 5) was isolated in 51% yield from the reaction of Nitron 2 in aqueous acetonitrile (50% v/v) with no added base. The yield of 8 increased to 75% upon addition of aqueous KOH (0.5 M). Trace amounts of triazabutadiene 8 (<1%) were also identified in the reaction of Nitron 2 in acetonitrile only. Anilino-substituted triazabutadienes are known oxidation products of corresponding amidrazones33,34. Early reports of the usage of Nitron in alkaline solution suggest formation of 8 (refs 23, 35). The isolation of 8 thus supports the proposed initial hydrolytic ring-opening of Nitron 2 (Fig. 4).

The structure of 8 obtained by X-ray crystallography (Supplementary Fig. 9) shows N1=N2 and C3=N4 in an s-trans conformation. The corresponding s-cis conformer 8′ is directly analogous to 6 and hence a possible precursor to amino radical 4. Rotational barriers of 3.3, 5.4 and 3.5 kcal mol−1 were calculated for triazabutadienes 6, 8 and 9, the potential precursors to radicals 3, 4 and 1 (Supplementary Fig. 10). A recent computational study of the electrocyclization of s-cis 9 reveals a high 38.6 kcal mol−1 barrier, which is substantially greater than the computed rotational energy barriers above3. This suggests that the s-trans/s-cis C–N rotational barrier is not limiting in the cyclization of these triazabutadienes.

Stirring 8 overnight in acetonitrile did not give any detectable formation of 4 even in the presence of equimolar Ag2O and NaOH (1 M). This supports a post-cyclization route for the formation of trace quantities of amino radical 4 from Nitron 2 under these experimental conditions from the subsequent hydrolysis of amido radical product 3. The stability of triazabutadiene 8, however, does not exclude the intermediacy of N-formyl triazabutadiene 6 in the formation of 3. We speculate that N-formylation of 8 could be essential to facilitate electrocyclization, and the mild hydrolysis of Nitron 2 provides selective access to 6.

An acetonitrile solution of 1,2,4-triphenyltriazolium tetrafluoroborate 10 remained unchanged for at least 10 days at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 11). Similarly, 99% v/v acetonitrile solutions of 10 containing 1% H2O and equimolar Ag2O and NaOH (1 M) showed no evidence of radical formation by EPR when left overnight at room temperature. These data highlight the importance of the exocyclic nitrogen on Nitron 2 to enable conversion to Blatter-type radicals. The presence of nitrogen in Nitron 2 presumably favours the initial hydration/ring-opening step and also stabilizes the radical product.

To optimize the conversion of 2 to 3, we screened a range of experimental conditions. Addition of small amounts of water (≤10 v/v%) to a solution of Nitron 2 in acetonitrile was found to improve the yield of radical 3; however, higher volumes resulted in significantly lower yields of radical and gave triazabutadiene 8 as major product (see Supplementary Methods). The oxidative cyclization of amidrazones is known to be accelerated by a variety of oxidants and catalysts30,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. Addition of Ag2O or PbO2 and base to acetonitrile solutions of 2 increased the rate of conversion although yields were similar. Additional solvents were explored (see Supplementary Methods); however, it appears that acetonitrile is fortuitously best for the conversion of Nitron 2 to radical 3. Optimal yields were obtained in the presence of 1% v/v water as co-solvent (82% after 72 h).

Scope of the new transformation

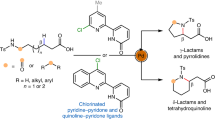

Our new facile one-pot preparation of radical 3, and novel substitution pattern, prompted us to explore other Nitron derivatives as substrates. Using the most recently reported literature synthesis of Nitron 2 (ref. 43), four additional derivatives 11–13 (Fig. 6) were prepared (see Supplementary Methods). Importantly, all Nitron derivatives could be converted to corresponding Blatter radicals 14–16 in one pot in 42–67% yields using the optimized conditions described above. Conversion of Nitron derivatives 11 and 12 to corresponding amido radicals 14 and 15 in acetonitrile required oxidant and base for significant reaction to occur overnight. By contrast, Nitron derivatives 13a and 13b were unstable and converted spontaneously to radicals 16a and 16b. We speculate that spontaneous conversion of 13a,b into Blatter-type radicals is facilitated by easy tautomerization (cf. Fig. 1), which is not possible for 11 or 12. These initial results highlight the potential of the route to a broader range of stable C(3)-amido-substituted Blatter radicals.

In summary, a novel simple one-pot reaction of Nitron 2 to give new stable radical 3 was observed in acetonitrile, which is the first example to our knowledge of a Blatter-type system with an amido-substituent at C(3). Such derivatives are likely to be challenging to access by conventional routes. Conversion of amido radical 3 to amino radical 4 was achieved in strongly basic solutions in good yield. Remarkably, the benzotriazinyl radical component remained unaltered under these conditions highlighting the intrinsic stability of these radicals. As well as the potential for more diverse properties, this alternative substitution of 3 and 4 opens up new avenues for modification of such radical systems towards functional materials, and for the incorporation of the benzotriazinyl radical system into larger molecular assemblies. Our preliminary synthetic studies of derivatives of Nitron provided access to additional novel radicals 14–16. We propose that the formation of radical 3 depends on the initial hydrolytic ring opening of Nitron 2 to amidrazone 5 followed by oxidative cyclization. Future work will explore the full scope of this new reaction, and using the novel C(3)-amido and amino functionalities as handles for further modification.

Methods

Optimized method for conversion of Nitron 2 to C(3)-amido radical 3

Nitron (0.99 g, 16 mmol) was dissolved in acetonitrile (99 ml) along with 1% water (1 ml) and stirred with exposure to air for 72 h. The solution was then dried in vacuo to give crude black crystals. Column chromatographic purification of the crude black crystals (98:2 DCM:MeOH), where the major product 3 eluted as a dark red fraction, followed by concentration under reduced pressure, yielded a black solid. The solid was then recrystallized from minimum hot ethanol to yield amido radical 3 as black crystals (0.85 g, 82%). m.p. 143–145 °C; Elemental analysis: Calcd. For C20H15N4O: C, 73.38; H, 4.62; N, 17.11; Found: C, 73.19; H, 4.65; N, 17.07; IR: 3,070, 2,925, 1,681, 1,586, 1,483, 1,370, 1,204, 1,077, 841, 760, 692, 612, 552, 495 cm−1; MS (ESI, m/z, %): 327 (M+, 100%), 328 ([M+H]+, 69.53%), 329 ([M+2H]+, 39.99%), 330 ([M+3H]+, 4.91%). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. For C20H15N4O: 327.1246; Found: 327.1252 (within 1.0 p.p.m.).

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. For the experimental and computational procedures, and spectroscopic and physical data of compounds, see Supplementary Methods. The CCDC 1411555, CCDC 1484332 and CCDC 1411554 contain the crystallographic data for compounds 3, 4 and 8, respectively (Supplementary Figs 1, 2, 5 and 9, Supplementary Table 7). These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk). For cyclic voltammograms of 3 and 4, see Supplementary Figs 4 and 7, and Supplementary Table 4. For EPR spectra of compounds 4, 14, 15, 16a and 16b, see Supplementary Figs 6 and 12. For IR and UV-Vis spectra of 3 and 4, see Supplementary Figs 13–15 and Supplementary Tables 5 and 6. For mass spectra of the compounds in this article, see Supplementary Figs 16–31. For NMR spectra of the compounds in this article, see Supplementary Figs 32–44.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Grant, J. A. et al. New Blatter-type radicals from a bench-stable carbene. Nat. Commun. 8, 15088 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15088 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Blatter, H. M. & Lukaszewski, H. A new stable free radical. Tet. Lett. 9, 2701–2705 (1968).

Berezin, A. A., Constantinides, C. P., Drouza, C., Manoli, M. & Koutentis, P. A. From Blatter radical to 7-substituted 1,3-diphenyl-1,4-dihydrothiazolo[5′,4′:4,5]benzo[1,2-e][1,2,4]triazin-4-yls: toward multifunctional materials. Org. Lett. 14, 5586–5589 (2012).

Bodzioch, A., Zheng, M., Kaszyński, P. & Utecht, G. Functional group transformations in derivatives of 1,4-dihydrobenzo[1,2,4]triazinyl radical. J. Org. Chem. 79, 7294–7310 (2014).

Constantinides, C. P. et al. A magnetostructural investigation of an abrupt spin transition for 1-phenyl-3-trifluoromethyl-1,4-dihydrobenzo[e][1,2,4]triazin-4-yl. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 11906–11909 (2014).

Constantinides, C. P., Koutentis, P. A., Krassos, H., Rawson, J. M. & Tasiopoulos, A. J. Characterization and magnetic properties of a ‘super stable’ radical 1,3-diphenyl-7-trifluoromethyl-1,4-dihydro-1,2,4-benzotriazin-4-yl. J. Org. Chem. 76, 2798–2806 (2011).

Takahashi, Y., Miura, Y. & Yoshioka, N. Synthesis and properties of the 3-tert-butyl-7-trifluoromethyl-1,4-dihydro-1-phenyl-1,2,4-benzotriazin-4-yl radical. New J. Chem. 39, 4783–4789 (2015).

Yan, B., Cramen, J., McDonald, R. & Frank, N. L. Ferromagnetic spin-delocalized electron donors for multifunctional materials: π-conjugated benzotriazinyl radicals. Chem. Commun. 47, 3201–3203 (2011).

Ratera, I. & Veciana, J. Playing with organic radicals as building blocks for functional molecular materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 303–349 (2012).

Kaszyński, P., Constantinides, C. P. & Young, V. G. Jr. The planar Blatter radical: structural chemistry of 1,4-dihydrobenzo[e][1,2,4]triazin-4-yls. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 11149–11152 (2016).

Jasiński, M., Szczytko, J., Pociecha, D., Monobe, H. & Kaszyński, P. Substituent-dependent magnetic behavior of discotic benzo-[e][1,2,4]triazinyls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 9421–9424 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Temperature tunable self-doping in stable diradicaloid thin-film devices. Adv. Mater. 27, 7412–7419 (2015).

Gallagher, N. M., Bauer, J. J., Pink, M., Rajca, S. & Rajca, A. High-spin organic diradical with robust stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 9377–9380 (2016).

Ciccullo, F. et al. A derivative of the Blatter-radical as a potential metal-free magnet for stable thin films and interfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 1805–1812 (2016).

Demetriou, M., Berezin, A. A., Koutentis, P. A. & Krasia-Christoforou, T. Benzotriazinyl-mediated controlled radical polymerization of styrene. Polym. Int. 63, 674–679 (2014).

Areephong, J. et al. Polymérisation radicalaire contrôlée vivante médiée par une triazine. WO Patent 2015/061189 A1 (2015).

Areephong, J. et al. Triazine-mediated controlled radical polymerization: new unimolecular initiators. Polym. Chem. 7, 370–374 (2016).

Morgan, I. S. et al. Coordination complexes of a neutral 1,2,4-benzotriazinyl radical ligand: synthesis, molecular and electronic structures, and magnetic properties. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 15843–15853 (2015).

Morgan, I. S. et al. 1-Phenyl-3-(pyrid-2-yl)benzo[e][1,2,4]triazinyl: the first ‘Blatter radical’ for coordination chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 53, 33–35 (2014).

Fauconnier, T., Lock, C. J. L., Bell, R. A., Britten, J. F. & Rainsford, K. D. Studies of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: azapropazone. Can. J. Chem. 72, 382–389 (1994).

Brown, J. M. & Wang, L. H. Tirapazamine: laboratory data relevant to clinical activity. Anti-Cancer Drug Des. 13, 529–539 (1998).

Junnotula, V., Sarkar, U., Sinha, S. & Gates, K. S. Initiation of DNA strand cleavage by 1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxide antitumor agents: mechanistic insight from studies of 3-methyl-1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 1015–1024 (2009).

Brown, M. & Wilson, W. Exploiting tumour hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 437–447 (2004).

Busch, M. Ueber endimino-triazole. Chem. Ber. 38, 856–860 (1905).

Färber, C., Leibold, M., Bruhn, C., Maurer, M. & Siemeling, U. Nitron: a stable N-heterocyclic carbene that has been commercially available for more than a century. Chem. Commun. 48, 227–229 (2012).

Massey, R. S., Collett, C. J., Lindsay, A. G., Smith, A. D. & O’Donoghue, A. C. Proton transfer reactions of triazol-3-ylidenes: kinetic acidities and carbon acid pKa values for twenty triazolium salts in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 20421–20432 (2012).

Tucker, D. E. et al. Proton transfer reactions of N-aryl triazolium salts: unusual ortho-substituent effects. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 28, 108–115 (2015).

Allen, F. The Cambridge Structural Database: a quarter of a million crystal structures and rising. Acta Crystallogr. B58, 380–388 (2002) (Version 5.37, Nov. 2015).

Lahti, P. M. Structure-property relationships for metal-free organic magnetic materials. Adv. Phys. Org. Chem. 45, 93–170 (2011).

Lahti, P. M. in Molecule-based Magnetic Materials ACS (1996).

Berezin, A. A. et al. Route to benzo- and pyrido-fused 1,2,4-triazinyl radicals via N′-(het)aryl-N′-[2-nitro(het)aryl]hydrazides. J. Org. Chem. 79, 314–327 (2014).

Constantinides, C. P., Obijalska, E. & Kaszyński, P. Access to 1,4-dihydrobenzo[e][1,2,4]triazin-4-yl derivatives. Org. Lett. 18, 916–919 (2016).

Constantinides, C. P. & Koutentis, P. A. in Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry Vol. 119, 173–207Elsevier (2016).

Marckwald, W. & Wolff, P. Ueber das diphenylanilguanidin. Chem. Ber. 25, 3116–3119 (1892).

Raiford, L. C. & Daddow, W. T. The reactions of some carbonyl compounds with phenylhydrazine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 53, 1552 (1931).

Busch, M. & Mehrtens, G. Ueber endimino-triazole II. Chem. Ber. 38, 4049–4068 (1905).

Al-Noaimi, M. Z. et al. Metal-assisted oxidative cyclization of arylamidrazones I. synthesis of 3-acetyl-1,4-dihydro-1-phenyl-1,2,4-benzotriazine. Monatsh. Chem. Chem. Mon. 137, 745–750 (2006).

Arndt, F. & Eistert, B. Umlagerung phenylierter azo-dicarbonamide in benzotriazine. Chem. Ber. 60, 2598–2602 (1927).

Kadirov, M. K., Buzykin, B. I. & Gazetdinova, N. G. Electron spin and electron nuclear double resonances of the stable 1-(4-nitrophenyl)-3-phenyl-1,4-dihydro-1,2,4-benzotriazin-4-yl free radical. Russ. Chem. Bull. 51, 1796–1799 (2002).

Mukai, K. et al. Magnetic-properties of 1,4-dihydro-1,2,4-benzotriazin-4-yl radicals. Chem. Phys. Lett. 224, 569–575 (1994).

Neugebauer, F. A. & Umminger, I. Über 1,4-dihydro-1,2,4-benzotriazinyl-radikale. Chem. Ber. 113, 1205–1225 (1980).

Constantinides, C. P., Koutentis, P. A. & Loizou, G. Synthesis of 7-aryl/heteraryl-1,3-diphenyl-1,2,4-benzotriazinyls viapalladium catalyzed Stille and Suzuki-Miyaura reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 9, 3122–3125 (2011).

Koutentis, P. A. & Lo Re, D. Catalytic oxidation of N-phenylamidrazones to 1,3-diphenyl-1,4-dihydro-1,2,4-benzotriazin-4-yls: an improved synthesis of Blatter’s radical. Synthesis 2010, 2075–2079 (2010).

Kriven’ko, A. & Morozova, N. Synthesis of 1,4-diphenyl-3-phenylimino-1,2-dihydro-1,2,4-triazolium hydroxide (Nitron). Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 79, 506–507 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank the EPSRC (Grant Ref. EP/L504762/1) for financial support of D.E.T. and Dr A.S. Batsanov for collecting SXRD data for 4. The authors thank Professor Peter O’Brien from the Department of Chemistry in the University of York for helpful discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.C.O’D. conceived the project. A.M.C.O’D. and V.C. contributed to the design of the experiments. J.A.G., Z.L., D.E.T. and B.M.H. performed the experiments. D.S.Y. and R.K. analysed X-ray structures and CV data, respectively. M.A.F. performed the computational analysis. A.M.C.O’D. and V.C. wrote the manuscript and all authors contributed to data analysis and scientific discussion.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary figures, supplementary tables, supplementary methods and supplementary references. (PDF 3021 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Grant, J., Lu, Z., Tucker, D. et al. New Blatter-type radicals from a bench-stable carbene. Nat Commun 8, 15088 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15088

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15088

This article is cited by

-

Synthesis of 1,4-dihydro-1,2,4-benzotriazin-4-yl radicals (microreview)

Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds (2022)

-

Controlled polymerization of styrene in the presence of Blatter’s radicals

Russian Chemical Bulletin (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.