Abstract

Shedding new light on conventional batteries sometimes inspires a chemistry adoptable for rechargeable batteries. Recently, the primary lithium-sulfur dioxide battery, which offers a high energy density and long shelf-life, is successfully renewed as a promising rechargeable system exhibiting small polarization and good reversibility. Here, we demonstrate for the first time that reversible operation of the lithium-sulfur dioxide battery is also possible by exploiting conventional carbonate-based electrolytes. Theoretical and experimental studies reveal that the sulfur dioxide electrochemistry is highly stable in carbonate-based electrolytes, enabling the reversible formation of lithium dithionite. The use of the carbonate-based electrolyte leads to a remarkable enhancement of power and reversibility; furthermore, the optimized lithium-sulfur dioxide battery with catalysts achieves outstanding cycle stability for over 450 cycles with 0.2 V polarization. This study highlights the potential promise of lithium-sulfur dioxide chemistry along with the viability of conventional carbonate-based electrolytes in metal-gas rechargeable systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To satisfy the growing demand on energy storage devices for emerging electric vehicles and grid-scale energy storage markets, recent efforts have been devoted to exploring a new battery chemistry that can outperform the current state-of-the-art lithium ion batteries1,2,3. Revisiting the conventional primary batteries can offer insight for developing a novel rechargeable chemistry by taking advantage of the recent advances in the fundamental understanding of battery science4,5,6. One recent example is the development of rechargeable lithium-sulfur dioxide (Li-SO2) batteries. The primary Li-SO2 battery offers a high energy density in a wide operating temperature range with exceptionally long shelf-life and has thus been commercialized for military and aerospace applications since it was developed in the late 1960s (refs 7, 8, 9, 10). Recently, the Li-SO2 chemistry was revisited and proposed as a promising rechargeable battery chemistry11,12. Under an analogous cell configuration adopted from lithium-oxygen batteries, it has been demonstrated that a reversible electrochemical reaction between Li and SO2 is possible with the formation and decomposition of lithium dithionite (Li2S2O4). Similar to lithium-oxygen and lithium-sulfur batteries6, the absence of heavy transition metals in the redox reaction can result in a high energy density reaching 1,132 Wh kg−1 based on the mass of Li2S2O4. Moreover, the intrinsically smaller polarization and higher gas efficiency were observed to be advantageous compared with lithium-oxygen systems, making the Li-SO2 battery a potential metal-gas rechargeable battery chemistry.

Recent studies have revealed that the properties of the electrolyte in metal-gas batteries play a pivotal role in determining the nature of discharge products and the rechargeability of the system13,14,15,16,17,18,19. The discharge mechanisms and nature of discharge products such as their morphology and stability can be significantly altered by the properties of the electrolyte, such as donor numbers or dielectric constants20,21,22,23,24,25. The critical dependency on the electrolyte in the metal-gas system compared with conventional lithium/sodium ion batteries is most likely due to the generation of gas radicals, which are an important intermediate for the discharge reaction. Depending on the stability of the electrolyte, the gas radicals can react with the electrolyte solvent rather than the desirable alkali ions, such as lithium or sodium, which can form rechargeable discharge products15,26,27. Moreover, the stability of the intermediate alkali–radical complex is governed by the nature of the electrolyte and can thus alter the discharge paths21,22,23. In the early development of rechargeable lithium-oxygen or sodium-oxygen batteries, the use of carbonate-based electrolytes yielded side reaction products; thus, an appropriate charging process could not be achieved14,15,19. The organic carbonate was highly vulnerable to chemical attacks by the oxygen radicals generated during the discharge process14,15,26,28. This finding led to the overall perception that carbonate-based electrolytes cannot be considered for metal-air batteries. Nevertheless, carbonate-based electrolytes possess several benefits, including high ionic conductivity and wide electrochemical windows, which have made them a common electrolyte for the well-developed lithium/sodium ion batteries technology29,30. Moreover, the good lithium metal compatibility and chemical stability can be potential merits for lithium-air battery systems, which are expected to use lithium metal anodes and operate in an open system.

In this work, we evaluate the feasibility of implementing a conventional carbonate-based electrolyte in a Li-SO2 battery and investigate how the electrochemical properties are affected. Although the stability of SO2 gas radicals during the discharge process is unknown, we observe that the chemical reactivity of SO2− towards organic carbonates is both thermodynamically and kinetically prohibited according to density functional theory (DFT) calculations. It is also experimentally verified that a Li-SO2 battery employing ethylene carbonate (EC) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC) as electrolytes can reversibly operate with the formation and decomposition of a Li2S2O4 discharge product. Furthermore, it is revealed that the power capability and cycling properties of the Li-SO2 batteries are remarkably improved compared with those using an ether-based electrolyte because of its higher ionic conductivity and better compatibility with the lithium metal anode. By introducing a soluble catalyst, cycling over 450 cycles is demonstrated with a high energy efficiency, exhibiting an overall polarization of 0.2 V during cycling, which has not yet been achieved in either lithium-oxygen or Li-SO2 batteries. This report is the first to demonstrate that conventional carbonate-based electrolytes can be successfully applied in rechargeable metal-gas systems, opening up a new avenue towards high-efficiency rechargeable metal-gas batteries.

Results

Theoretical investigation of Li-SO2 chemistry

The basic principle of Li-SO2 battery operation is based on the simple electrochemical reaction between Li and SO2 gas, whose general discharge reaction is31,32:

In the cathode reaction, the SO2 collects the electron from the electrode and forms the intermediate dithionite ion (S2O42−) before precipitating as solid Li2S2O4, the final discharge product. However, recent findings on O2− in the lithium-oxygen chemistry suggest that the intermediate S2O42− may undergo chemical interactions with surrounding electrolyte molecules, which may lead to alternation in the discharge reaction path21,22. To investigate this early stage of the discharge reaction, we used DFT calculations coupled with the Poisson–Boltzmann (PB) solvation model to explore the reaction thermodynamics of Li-SO2 batteries. Moreover, similar calculations were performed under different electrolyte conditions to probe the effect of the surrounding electrolyte molecules on this discharge reaction. We selected two types of electrolyte: a conventional carbonate-based electrolyte (EC/DMC, 1:1 volume mixture) and ether-based electrolyte (tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether, TEGDME), both of which have been widely used for lithium-ion and lithium-air rechargeable batteries33,34,35,36. Figure 1a shows the energy of the first electron transfer step starting from the SO2 molecule in a gas phase to SO2− in the respective electrolyte solution. A slightly different energy trajectory of the electron transfer was observed in the two electrolyte systems, where the SO2− in the EC/DMC is more stable by 0.30 eV than that in the TEGDME. The slightly different stabilization of the charged species is mainly attributed to the strong solvating ability of the carbonate-based electrolyte with the high dielectric constant (ɛ∼35)20,37.

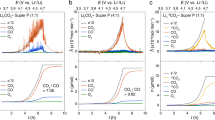

(a) Energy diagrams for electrochemical reduction reaction of SO2 gas under EC/DMC and TEGDME. (b) Energy profiles for ICF of chemical EC decomposition reaction by O2− (blue) and SO2− (red). (c) Reaction pathway between SO2− and lithium ions with corresponding energy profiles under EC/DMC (red) and TEGDME (blue).

Under normal operation conditions, it is expected that the electrochemically reduced SO2− would react with lithium ions, leading to the formation of solid discharge products. However, the SO2− in Li-SO2 cells may also undergo a chemical reaction with the carbonate-based electrolyte by nucleophilic attack, that is, electrolyte decomposition similar to the behaviour of O2− in the electrolytes of lithium-oxygen batteries13,26. The plausibility of this chemical reaction can be determined by assessing the energetics of the initial complex formation (ICF) process involving the electrolyte molecule and SO2−20,26,27. Figure 1b presents the energy profile for the ICF processes involving EC molecules with the nucleophilic attack of SO2− compared with that of the previously known case of O2−. Consistent with earlier theoretical20,26 and experimental studies14, the ICF of EC-O2 (blue dotted line) is a energetically downhill process with a moderate activation barrier, which indicates the instability of the carbonate electrolyte on exposure to O2−. However, it is noted that the ICF of EC-SO2 (red dotted line) is energetically unfavourable by 0.24 eV. Moreover, the activation energy that needs to be overcome is as high as 1.08 eV, indicating that it is also kinetically hindered. This finding implies that the electrochemically driven SO2− molecule is likely to be stable in contact with the carbonate-based electrolyte without triggering severe degradation of the electrolyte.

The initial discharge process was investigated in further detail by evaluating the energies of each elementary reaction step from the SO2− molecule to the final Li2S2O4 product; however, the detailed electrochemical mechanism of Li-SO2 batteries remains poorly understood to date. Figure 1c illustrates the most favourable discharge paths with each step denoted with energies in TEGDME (blue line) and EC/DMC (red line) electrolytes using the PB solvation model, where only the dielectric constant of the specific solvent is considered. Note that the dielectric constant of organic electrolytes can slightly alter with the addition of SO2 into the solvents as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 and the measured dielectric constant of organic solutions dissolving SO2 was used for theoretical calculations in this study. Moreover, it should be noted that the energy profiles of elementary cathode reactions in Fig. 1c are described without consideration of the energetics of the anode reaction and the total reaction energetics including the anodic part are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. For TEGDME, which has a low dielectric constant (weak electrostatic interaction), the initial process proceeds with SO2− combining with lithium ions, forming the neutral intermediate species of LiSO2. The additional chemical association of SO2− and lithium ions to LiSO2 results in the formation of the final product of Li2S2O4 during the continuous downhill energy process. In contrast, for EC/DMC with a relatively high dielectric environment (strong electrostatic interaction), SO2− is prone to undergo a dimerization reaction, forming S2O42− rather than a neutral species with lithium ions, which is a well-known chemical equilibrium of 2SO2−↔S2O42− in organic chemistry and biochemistry38,39,40. In the subsequent reaction steps, two lithium ions are associated with S2O42−, forming LiS2O4− and Li2S2O4, undergoing substantial uphill energy processes before the precipitation of the final product. The notably different initial discharge steps in the two electrolytes are attributed to their distinct solvating characters, where the high-dielectric solvent (EC/DMC) stabilizes the charged species such as S2O42− more effectively, preserving the strong solvation shell, and the low-dielectric solvent (TEGDME) fails to stabilize them, thus preferring to form a neutral species (LiSO2) in the reaction. This theoretical tendency is in accordance with the previous experimental findings that the chemical equilibrium constant of dimerization reaction to dithionite ion has a positive correlation with the dielectric constant of organic solvent media40. It is noteworthy that the previously proposed discharge mechanism of the primary Li-SO2 battery was based on the formation of S2O42− rather than SO2− or LiSO2 (refs 32, 38). It is our speculation that this finding is most likely due to the use of an acetonitrile-based electrolyte in most primary Li-SO2 batteries8,9,10,32, which has a high dielectric constant (ɛ∼35.9)41,42 comparable to that of EC/DMC. Although the overall processes to attain the final product of Li2S2O4 are thermodynamically favourable with identical energy change of overall reactions in both electrolytes as shown in Supplementary Table 1, it should be noted that the energy profiles along the elementary reaction pathways for Li-SO2 batteries were significantly different depending on the type of electrolyte. One energy profile consisted of a monotonous downhill process (TEGDME), and the other consisted of a mixed uphill and downhill process involving a significant energy barrier (EC/DMC). This difference in the reaction energetics is expected to affect the nature of the formation of solid discharge products for the Li-SO2 battery depending on the type of electrolyte, which will be discussed more in the experimental section.

Feasibility of Li-SO2 chemistry in carbonate electrolytes

Inspired by the theoretical findings, we constructed Li-SO2 cells using the conventional carbonate electrolyte EC/DMC (1:1 volume ratio with 1 M lithium hexafluorophosphate) and examined the stability of the rechargeable Li-SO2 chemistry. Figure 2a presents the galvanostatic voltage profile during the first cycle of the Li-SO2 cell. The electrochemical profile at 0.2 mA cm−2 resembles the typical profile of the Li-SO2 cells using an ether-based electrolyte in a previous study12. To confirm the reversible electrochemical reactions, we performed several analyses of Li-SO2 cells using the galvanostatic intermittent titration technique, differential electrochemical mass spectroscopy (DEMS), X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Figure 2b indicates that the equilibrium potentials measured by galvanostatic intermittent titration technique are in an agreement with the thermodynamic potential of Li2S2O4 (∼3 V)43, which supports the idea that the main reaction involves the formation and decomposition of Li2S2O4. Furthermore, the DEMS results in Fig. 2c indicate that the SO2 gas was solely detected without the evolution of other gases during the entire charge process, demonstrating the reversible and stable charge reaction occurring in the Li-SO2 cell. Considering that the oxygen evolution during the charging of conventional lithium-oxygen cells is typically accompanied by the release of considerable amounts of carbon dioxide due to electrolyte decomposition15,17 and carbon deterioration44,45, the absence of carbon dioxide in this experiment supports the idea that the EC/DMC electrolyte as well as the carbon electrode used for Li-SO2 cells remain stable during the cell operation. In addition to the evidence on a gas phase evolution of SO2 through in situ gas analyses, the characterization of electrolytes after charge of the Li-SO2 cells with ultraviolet –visible spectroscopy in Supplementary Fig. 2 clearly confirms the reversible evolution of SO2 from the electrolyte solution46,47.

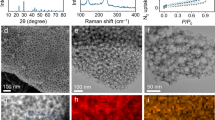

(a) Galvanostatic discharge/charge profile of Li-SO2 cell at a current density of 0.2 mA cm−2. (b) Galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT) analysis result of Li-SO2 cell. The specific capacity was normalized by the mass of carbon loading whose average mass in a gas electrode was ∼0.8±0.1 mg. (c) In situ gas analysis during charge process of the Li-SO2 cell by DEMS. (d) Ex situ X-ray diffraction spectra of gas electrodes for Li-SO2 cells. (e) Corresponding ex situ SEM images of the gas electrodes of Li-SO2 cells (scale bar, 300 nm; scale bar, 5 μm (2–5)).

To further verify the electrochemical reaction, we carefully performed ex situ analyses on the gas electrodes of Li-SO2 cells at different states of charge or discharge, as shown in Fig. 2a. The ex situ X-ray diffraction spectra in Fig. 2d reveal that characteristic peaks of Li2S2O4 appear and grow during discharge without any notable by-products, followed by the reduction of these peaks during the charge and their complete disappearance after the end of the charge31,48. These results evidently confirm that the reversible formation and decomposition of Li2S2O4 is the major electrochemical reaction occurring in the Li-SO2 system using an EC/DMC electrolyte, which is consistent with the DFT calculations. In addition, the formation and decomposition of Li2S2O4 can be directly probed by tracking the morphological evolution on the electrode in the ex situ SEM images in Fig. 2e. It is apparent that two-dimensional plates begin to appear on the carbon gas electrode on discharge and grow up to ∼5 μm in size, covering all the carbon surfaces at the end of discharge. On the charge process, Li2S2O4 gradually disappears; at the end of charge to 4.2 V, no micron plate was observed in the electrode, and the porous structure of the gas electrode was well recovered to its pristine state, which is in a good agreement with the X-ray diffraction results. Note that the morphological feature of the discharge product is slightly different from that of the Li2S2O4 formed using the TEGDME electrolyte in our previous study12. As carefully compared in Supplementary Fig. 3, the Li2S2O4 initially forms needle-like precipitates and grows into numerous nanoribbons for the TEGDME electrolyte, in contrast to the micron-sized Li2S2O4 plate in the EC/DMC electrolyte. Interestingly, the morphology of discharge products has recently been regarded as an important clue to understanding the discharge mechanism of metal-oxygen batteries21,22,23,49. In the lithium-oxygen battery system, for instance, highly solvating electrolytes with a high donor number or solvating additives promote the nucleation and growth of the crystalline toroidal Li2O2 with a typically large particle size by driving the solution-mediated process, whereas electrolytes with low donor numbers tend to form film-like discharge products on the surface of the electrode21,22,50. According to the reaction pathways examined by the DFT calculations in Fig. 1c, it is believed that the intermediate energy uphill processes in the EC/DMC electrolyte would play an important role in governing the nucleation of solid precipitates because of the critical energy barrier, in contrast to the case of TEGDME, where there is no energy barrier for the discharge process. Because the number of nuclei is generally inversely proportional to the nucleation energy barriers, we presumed that a small number of nuclei generated under highly solvating EC/DMC electrolyte yield to form the relatively well-grown micron-sized discharge products of Li2S2O4. Further study must be performed to understand the relationship between the discharge mechanism and the feature of the discharge products in the Li-SO2 system.

Performance of Li-SO2 cells using carbonate electrolytes

Having confirmed the reversible Li2S2O4 formation in the carbonate-based electrolyte, the electrochemical properties of Li-SO2 cells were comparatively investigated in EC/DMC and TEGDME electrolytes. Figure 3a,b compare the power capability of Li-SO2 cells under current rates ranging from 0.2 to 5.0 mA cm−2 during discharge. Interestingly, a significantly higher rate capability is achievable with the cell employing the EC/DMC electrolyte for an identical cell configuration. Although similar discharge capacities are delivered at a low current rate of 0.2 mA cm−2 for the two cases, the cell with EC/DMC is capable of delivering more than 70% of the initial capacity even at 25 times higher current density; in contrast, the cell with TEGDME exhibits a negligible capacity at the same current rate. It is speculated that the facile ion transport in EC/DMC, which exhibits ∼4 times higher ionic conductivity than TEGDME, as shown in Supplementary Table 2, contributes to the high rate capability of the Li-SO2 cell. To verify the reversible Li2S2O4 formation/decomposition in such a high rate operation, the ex situ analyses were performed again under the condition shown in Supplementary Fig. 4, which revealed identical results regardless of the applied current densities. In Fig. 3c, the cycling properties of Li-SO2 cells were comparatively investigated at a constant rate of 0.2 mA cm−2. The Li-SO2 cell with EC/DMC stably operated over 80 cycles, whereas that with the TEGDME electrolyte maintained ∼20 cycles, which is consistent with the previous report12. Moreover, better cycle stability of the cell with EC/DMC was again confirmed with the larger capacity utilization of 1,000 mAh g−1, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. Note that no special treatment such as nanoscale gas electrode design or the use of a catalyst was applied during the test, under which conventional lithium-oxygen or sodium-oxygen batteries would exhibit significantly less cycle stability51,52,53,54. Even at a higher current density of 1 mA cm−2, the Li-SO2 cell with EC/DMC could sustain a high cycle stability of ∼50 cycles, as observed in Supplementary Fig. 6, supporting the idea that simply replacing the electrolyte could markedly enhance the cycling properties of Li-SO2 cells. The superior cycling performance of the Li-SO2 cell with EC/DMC is attributed to the stability of the carbonate-based electrolyte in the presence of the strongly solvated intermediate SO2− product and the better chemical compatibility with the lithium anode, which will be discussed later.

(a,b) Discharge rate capability of Li-SO2 cell: (a) with carbonate electrolyte, (b) with ether electrolyte and (c) cycle properties of Li-SO2 cells at 0.2 mA cm−2. (d) Electrochemical profiles of Li-SO2 cells with a soluble catalyst. (e) X-ray diffraction spectra of discharged and recharged gas electrode of Li-SO2 cell with soluble catalyst. (f,g) Electrochemical performance of Li-SO2 cells with soluble catalyst containing carbonate-based electrolyte: (f) power capability of the cells under limited capacity of 0.5 mAh, (g) cyclability of the cell at 1 mA cm−2. (inset: electrochemical profiles during 450 cycles.) The specific capacity was normalized by the mass of carbon loading whose average mass in a gas electrode was ∼0.8±0.1 mg.

To examine the practical viability of the Li-SO2 cells, it was attempted to further enhance the energy efficiency using an appropriate catalyst to promote the charging reaction. A soluble catalyst of 5,10-dimethylphenazine (DMPZ) was introduced into the electrolyte to decrease the charge polarization, which was recently reported as an efficient soluble catalyst for lithium-oxygen batteries55. Figure 3d presents the characteristic discharge/charge profiles with the DMPZ catalysts for the two Li-SO2 cells, which reveals substantial reduction in the charge overpotential. The charging voltage, that is, the oxidation potential of DMPZ, in the TEGDME electrolyte was analogous to that in our previous study in lithium-oxygen batteries55. However, surprisingly, the cell with the DMPZ catalyst in the EC/DMC electrolyte could be recharged at a voltage plateau of ∼3.0 V, which is almost identical to the thermodynamic potential of Li2S2O4. Thus, the overall polarization of the cells was only 0.2 V, resulting in an energy efficiency of ∼93.3%, one of the highest values accomplished with lithium-gas-type batteries. This finding indicates that DMPZ is not only capable of chemically decomposing Li2S2O4, similar to the case of Li2O2 in lithium-oxygen batteries, but also enables much a higher charging efficiency in the carbonate-based electrolyte. To confirm this unexpected dependency of the redox potential of DMPZ on the electrolyte species, the cyclic voltammetry test and galvanostatic charging in the inert atmosphere were performed again for the DMPZ dissolved in each electrolyte with the three-electrode configuration, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. DMPZ consistently exhibited a lower oxidation potential in EC/DMC than in TEGDME by ∼0.2 V. The lower oxidation potential of DMPZ under the carbonate electrolyte might be attributed to the strong stabilization effect on the charged species of DMPZ+ due to the highly solvating environment offered by the carbonate electrolytes. The alternation in the redox potential of soluble catalysts depending on the electrolyte media was also observed in a recent study, where the redox potential of a LiI catalyst was notably different in dimethoxyethane than in TEGDME56. Ex situ X-ray diffraction analysis confirmed that the catalytic activity of DMPZ in decomposing Li2S2O4 could be maintained even with the lower redox potential of DMPZ in EC/DMC. Figure 3e shows that characteristic diffraction patterns of Li2S2O4 were observed in the discharged electrode but disappeared after the charging, indicating the effective decomposition of the discharge product. Supplementary Fig. 8 further confirms the charging reaction based on the decomposition of Li2S2O4 by the DMPZ catalyst through X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and in situ gas analysis. On charging of the cell, the XPS signature of Li2S2O4 gradually fades away, which is accompanied by the evolution of SO2 without any other detectable gases, implying the efficient catalytic behaviour of DMPZ for Li-SO2 cells.

We further investigated the electrochemical performance of the Li-SO2 cell employing the carbonate electrolyte with the DMPZ catalyst. Figure 3f shows the power capability of the cell for current densities ranging from 0.2 to 5.0 mA cm−2 under a controlled capacity of 0.5 mAh. Although the overall polarization systematically increased as the applied current increased, the charge processes of all the cells could be performed below 4 V without exceeding the voltage limit, demonstrating the fast kinetics of the Li2S2O4 formation and decomposition aided by DMPZ. It was observed that the efficient catalytic activity of the DMPZ could also lead to a remarkable enhancement in the cycling performance of Li-SO2 cells. Figure 3g shows that the Li-SO2 cells employing EC/DMC with the DMPZ catalyst exhibit superior cycle stability of more than 450 cycles of 0.5 mAh, which has rarely been recorded for lithium-oxygen batteries with such a large absolute capacity. During 450 cycles of the Li-SO2 cells, the charging overpotential was only slightly increased, maintaining the high energy efficiency of the cell, as observed in the inset of Fig. 3g. This finding indicates that the catalytic activity of DMPZ is stably maintained and not consumed during the cell operations. All the electrochemical results support the idea that a battery with superior power, efficiency and reversibility is achievable using the Li-SO2 chemistry by employing a carbonate-based electrolyte and soluble catalyst.

Discussion

Despite the impressive cycle properties achieved with the catalyst, the origin of the cycle degradation should be understood for further development of Li-SO2 batteries. Given the improved cycle stability of the cell using the EC/DMC electrolyte, we attempted to comparatively elucidate how the different electrolytes affect the cycling performance by probing the respective degradation of the carbon gas electrode and lithium metal anode in addition to the electrolyte stability itself17,57. After the cell degradation in Fig. 3c, the cells were disassembled and each electrode was collected; the cells were then rebuilt with a fresh counter electrode and new electrolyte. Figure 4a compares the cycling properties of two rebuilt cells based on EC/DMC: one with the cycled lithium anode (red) and the other with the cycled gas electrode (blue). Interestingly, the Li-SO2 cell with the cycled lithium metal anode could reproduce the original cyclability of ∼80 cycles, which suggests that the lithium metal cycled in the EC/DMC electrolyte was not significantly degraded. Note that the experiment was performed without DMPZ catalysts; thus, the original cycle life was ∼80 cycles in Fig. 3c. However, the rebuilt cell with the cycled gas electrode could not cycle stably. This finding clearly indicates that the degradation of the gas electrode is the main cause of the overall cycle deterioration in Li-SO2 cells using the EC/DMC electrolyte. In contrast, the opposite result was observed for the same experiments conducted for the cells employing the TEGDME electrolyte, as shown in Fig. 4b. The rebuilt cell with the cycled gas-electrode exhibited similar cycle properties of ∼20 reversible cycles as the original cell in Fig. 3c. However, the cell with the cycled lithium metal anode could not stably function, as observed in Fig. 4b, indicating that the degraded lithium metal anode was the main cause of the rapid cycle deterioration of the Li-SO2 cells using the TEGDME electrolyte. The severe degradation of lithium metal was again supported by an experiment in which the lithium metal anode was replaced multiple times, which led to a comparable cycling property as that of the rebuilt cell using the cycled gas electrode, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. To confirm the higher stability of the lithium metal anode in EC/DMC, a lithium metal symmetric cell was constructed, as shown in Fig. 4c. The usage of the carbonate electrolyte led to a much smaller polarization and longer operating time than those using the ether electrolyte, which is in a good agreement with previous studies58,59. This finding supports the idea that the better cycling properties of the Li-SO2 cells employing EC/DMC are partly attributable to the highly stable lithium metal interfaces because of better lithium metal compatibility with the carbonate electrolyte.

(a,b) Cycle properties of rebuilt cells with cycled gas electrode or cycled lithium anode: (a) under carbonate electrolyte and (b) under ether electrolyte. The specific capacity was normalized by the mass of carbon loading whose average mass in a gas electrode was ∼0.8±0.1 mg. (c) Lithium symmetric cell test at a current density of 1 mA cm−2 with SO2-saturated EC/DMC (red) and TEGDME (blue). (d) X-ray diffraction spectra of gas electrode of Li-SO2 cells at the middle and end of cycles. (e) SEM images (scale bar, 500 nm) of gas electrode at the end of cycle and elemental mapping by energy-dispersive spectroscopy (scale bar, 50 μm). (f) XPS 2p spectra for gas electrode after cycling of Li-SO2 cell.

For a more comprehensive understanding of the cycle degradation of Li-SO2 cells employing the carbonate electrolyte, we examined the carbon gas electrode after the cycling. The X-ray diffraction patterns in Fig. 4d reveal that after charging, the Li2S2O4 discharge product was hardly detectable; however, the characteristic peak of Li2SO4 began to appear appreciably even after 40 cycles, and a substantial amount of Li2SO4 by-products are detected at the end of the cycles. Although the expected discharge product, Li2S2O4, was clearly decomposed in the cycled cathodes, it is speculated that the gradual deposition of the insulating by-products on the carbon gas electrode would have a negative effect on the cycling behaviour of Li-SO2 cells. Moreover, examination of the morphology of the cycled gas electrodes clearly revealed that all the active pores of the gas electrodes were mostly blocked, as observed in Fig. 4e. Energy-dispersive spectroscopy analysis revealed that the densely clogged pores of the cycled gas electrode were mainly composed of sulfur and oxygen. The gradual deposition of insulating by-products results in the significant increase of total impedances of Li-SO2 cells, which is confirmed through the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy analyses with cycling the cells as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. Consequently, the accumulation of inactive and insulating by-products on the pores of the gas electrode would restrict the active reaction sites and the transport of reactants, including lithium ions and SO2 gas, finally resulting in the cell failures. In previous studies on primary Li-SO2 batteries, the formation of such by-products has generally been attributed to the self-decomposition of Li2S2O4 due to its thermodynamic instability11,48,60. According to the XPS analysis of the surface of the cycled cathodes in Fig. 4f, four different oxidation states of sulfur were detected, including the residual discharge product, Li2S2O4, at 166.5 eV. The two major peaks at 168.7 and 169.8 eV are assigned to the sulfur from Li2SO3 and Li2SO4, respectively, which is consistent with our previous study.12 The presence of the Li2SO4 by-product corresponds well to the X-ray diffraction result in Fig. 4d. Note that a trace amount of elemental sulfur (164.1 eV) was detected in the XPS spectra, which hints at the formation mechanism of Li2SO4. According to the self-decomposition of Li2S2O4, which can occur spontaneously, as indicated by the DFT calculations in Supplementary Table 3, it should accompany the generation of elemental sulfur, that is, Li2S2O4 (s)→Li2SO4 (s)+S (s). The presence of both elemental sulfur and Li2SO4 in the cycled gas electrode strongly suggests that the self-decomposition of the discharge product can cause deterioration of the cycle performance. Conclusively, a strategy for improving the stability of discharge products and suppressing the formation of by-products should be further explored to develop a better-performing Li-SO2 battery.

We successfully employed a conventional carbonate-based electrolyte in rechargeable Li-SO2 batteries and validated the feasibility of the system through combined theoretical and experimental verifications. The chemical stability of the carbonate electrolyte against the reduced form of SO2 allowed Li-SO2 cells to be reversibly operated, unlike the conventional lithium-oxygen systems. The high ionic conductivity and chemical compatibility with the lithium metal anode led to a remarkable improvement of the Li-SO2 cell performances, including the power capability and cycle stability. Furthermore, the application of a DMPZ catalyst yielded one of the highest efficiencies (∼93.3%) and reversibilities (450 cycles) reported for metal-gas systems to date. Towards the realization of a practical rechargeable Li-SO2 battery system, several issues still need to be addressed, including the lack of fundamental understanding and safety issues regarding the use of a toxic gas. In this regards, more quantifiable characterization techniques inclusive of pressure monitoring61,62 and chemical titration methodology22,63, currently introduced in the research of metal-air batteries, should be considered for the elucidation of precise gas efficiency or side-reaction mechanism of the Li-SO2 chemistry in following studies. In addition, taking advantage of the commercialized primary Li-SO2 battery technology, closed-type pressurized systems could be one of the practically approachable models for the safe Li-SO2 secondary battery with potential merits of the enhanced operation voltage and the reversibility obtained in our preliminary experiments as described in Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Note 1. Nevertheless, this study offers insights to the metal-air battery community regarding the importance of the electrolyte and its compatibility with the lithium or sodium metal electrode considering that the exceptionally high theoretical capacity of lithium/sodium-oxygen batteries is partly attributed to the use of a metallic lithium or sodium electrode. Thus, more studies should focus on how to rationally control the interaction between the electrolyte and metal anodes in metal-oxygen batteries. We hope that this report will pave the way for a new field of Li-SO2 batteries as a promising next-generation battery system and spur vigorous discussions in the search for a robust electrolyte in the metal-air battery community.

Methods

Computational details

DFT calculations were performed using the Jaguar 8.9 software64 for molecular reaction energies under the PB implicit solvation condition. We used the exchange-correlation functional of B3LYP65,66 along with the Pople 6-311++G** basis set67. The ground electronic and geometric structures for molecular reaction intermediates were fully optimized for both gas and solution phases. Single-point solution phase calculations without relaxing the gas phase structure were conducted only for the transition state obtained from a simple quasi-Newton method that searches for the transition state nearest to the input guessed geometry. The initial guess for the transition state search was obtained by scanning the most unstable geometry along the expected reaction coordinates, and the obtained transition states were validated by checking the number of imaginary frequency from vibrational modes. We also used the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package68 for the calculations of the cohesive energy of crystal structures with the exchange-correlation function of Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof69. The electron–ion interaction was considered in the form of the projector augmented wave method with a plane wave up to an energy of 400 eV. Gamma-centred k-point grids of 10 × 10 × 10 for lithium metal, 5 × 5 × 5 for Li2S2O4 and 4 × 6 × 4 for Li2SO4 were generated. The ground electronic and geometric structures were fully optimized for the crystal and corresponding formula unit molecule for each crystal structure. Further details including solvent parameters (Supplementary Table 4) and hypothetical crystal structure (Supplementary Fig. 12) are discussed in Supplementary Information.

Preparation and assembly of Li-SO2 cells

For the preparation of carbon paste, Ketjen black carbon (EC 600JD; Ilshin Chemtech) was dispersed with polytetrafluoroethylene (60 wt% dispersion in H2O) binder in a mass ratio of 8:2 into a solution of isopropanol (>99.7%; Sigma-Aldrich) and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (99.5%, anhydrous; Sigma-Aldrich) with a volume ratio of 1:1. The carbon gas electrode was fabricated by casting the carbon paste on the carbon paper current collectors (TGP-H030; Toray, Japan) and dried overnight at 120 °C to evaporate the solvent and residual water. The average loading mass of the Ketjen black electrodes in a 1/2-inch diameter was ∼0.8±0.1 mg. Electrolytes of 1 M lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) dissolved in EC/DMC 1:1 vol% or TEGDME with water contents less than 20 p.p.m. measured by Karl-Fisher titration were used. The Li-SO2 cell was assembled using a Swagelok-type cell in a sequence of lithium metal (3/8-inch diameter), two sheets of Celgard 2400 separators (1/2-inch diameter) and the prepared carbon electrode (1/2-inch diameter) in an argon-filled glove box (O2 level <1 p.p.m. and H2O level <1 p.p.m.). The amount of electrolyte was 200 μl. For the electrolytes employing the soluble catalyst, 50 mM concentration of DMPZ was added to the prepared electrolytes. The gas electrode of individual cells was open to the SO2 gas after the cell assembly and stabilized during a relaxation time of 0.5 h before the cell tests.

Characterization of Li-SO2 cells

All the electrochemical tests for the Li-SO2 cells were performed using a potentiogalvanostat (WBCS 3000; WonA Tech, Korea) between 2.0 and 4.2 V at room temperature. For the lithium symmetric cell tests, a coin-type cell CR2032 was assembled with 1/2-inch diameter lithium foils as both the counter and working electrode and a slice of Celgard 2400 separator soaked with electrolytes. The electrolytes used for the lithium/lithium symmetric test were saturated with SO2 gas by bubbling in prepared electrolytes. Electrochemical impedance measurements were performed by using a potentio-galvanostat (VSP-300, Bio-Logic Science Instruments, France) at room temperature with a frequency range from 200 kHz to 50 mHz. A Bruker D2-Phaser with Cu-Kα radiation (γ=1.5406 Å) was used to obtain XRD spectra of the cathodes under an Ar atmosphere with an air-locking holder. The morphology of the products in the electrode was examined using FE-SEM (MERLIN Compact; Zeiss, Germany) after platinum coating. XPS (Thermo VG Scientific, Sigma Probe, UK) was used for the surface characterization of the cathodes in a argon atmosphere without air exposure. For the in situ gas analyses, a DEMS instrument constructed with the combination of a mass spectrometer (MS; HPR-20, Hiden Analytical) and potentiogalvanostat was used, as described in our previous report.12 In situ gas analyses were conducted using argon carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 10 ml min−1 during the charge process after the full relaxation of the DEMS cell. Dielectric constants of prepared solutions were measured at 20 °C by using Liquid Dielectric Constant Meter (Model 871; Nihon Rufuto, Japan). Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (Cary 5000; Agilent, USA) was used for SO2 solution characterizations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Park, H. et al. High-efficiency and high-power rechargeable lithium–sulfur dioxide batteries exploiting conventional carbonate-based electrolytes. Nat. Commun. 8, 14989 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14989 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Tarascon, J. M. & Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 414, 359–367 (2001).

Armand, M. & Tarascon, J. M. Building better batteries. Nature 451, 652–657 (2008).

Kang, K., Meng, Y. S., Bréger, J., Grey, C. P. & Ceder, G. Electrodes with high power and high capacity for rechargeable lithium batteries. Science 311, 977–980 (2006).

Abraham, K. M. & Jiang, Z. A polymer electrolyte‐based rechargeable lithium/oxygen battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 143, 1–5 (1996).

Arico, A. S., Bruce, P., Scrosati, B., Tarascon, J.-M. & van Schalkwijk, W. Nanostructured materials for advanced energy conversion and storage devices. Nat. Mater. 4, 366–377 (2005).

Bruce, P. G., Freunberger, S. A., Hardwick, L. J. & Tarascon, J.-M. Li-O2 and Li-S batteries with high energy storage. Nat. Mater. 11, 19–29 (2012).

Meyers, B. B. a. J. W. S. W. F. US Patent 3, 242 (1969).

Kilroy, W. P. & Dallek, S. Differential scanning calorimetry studies of possible explosion-causing mixtures in Li/SO2 cells. J. Power Sources 3, 291–295 (1978).

Dey, A. & Holmes, R. Safety studies on Li/SO2 cells I. Differential thermal analysis (DTA) of cell constituents. J. Electrochem. Soc. 126, 1637–1644 (1979).

Linden, D. & McDonald, B. The lithium-sulfur dioxide primary battery—its characteristics, performance and applications. J. Power Sources 5, 35–55 (1980).

Xing, H. et al. Ambient lithium–SO2 batteries with ionic liquids as electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 2099–2103 (2014).

Lim, H. D. et al. A New Perspective on Li–SO2 Batteries for Rechargeable Systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 9663–9667 (2015).

Freunberger, S. A. et al. The lithium–oxygen battery with ether‐based electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 8609–8613 (2011).

Freunberger, S. A. et al. Reactions in the rechargeable lithium–O2 battery with alkyl carbonate electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8040–8047 (2011).

McCloskey, B. D., Bethune, D. S., Shelby, R. M., Girishkumar, G. & Luntz, A. C. Solvents’ critical role in nonaqueous lithium–oxygen battery electrochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 1161–1166 (2011).

Chen, Y., Freunberger, S. A., Peng, Z., Bardé, F. & Bruce, P. G. Li–O2 battery with a dimethylformamide electrolyte. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7952–7957 (2012).

McCloskey, B. et al. Twin problems of interfacial carbonate formation in nonaqueous Li–O2 batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 997–1001 (2012).

Walker, W. et al. A rechargeable Li–O2 battery using a lithium nitrate/N, N-dimethylacetamide electrolyte. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 2076–2079 (2013).

Kim, J., Lim, H.-D., Gwon, H. & Kang, K. Sodium–oxygen batteries with alkyl-carbonate and ether based electrolytes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 3623–3629 (2013).

Lim, H.-K. et al. Toward a lithium–‘air’ battery: the effect of CO2 on the chemistry of a lithium–oxygen cell. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9733–9742 (2013).

Johnson, L. et al. The role of LiO2 solubility in O2 reduction in aprotic solvents and its consequences for Li–O2 batteries. Nat. Chem. 6, 1091–1099 (2014).

Aetukuri, N. B. et al. Solvating additives drive solution-mediated electrochemistry and enhance toroid growth in non-aqueous Li–O2 batteries. Nat. Chem. 7, 50–56 (2015).

Burke, C. M., Pande, V., Khetan, A., Viswanathan, V. & McCloskey, B. D. Enhancing electrochemical intermediate solvation through electrolyte anion selection to increase nonaqueous Li–O2 battery capacity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 9293–9298 (2015).

Kwabi, D. G. et al. Chemical instability of dimethyl sulfoxide in lithium–air batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 2850–2856 (2014).

Kim, J. et al. Dissolution and ionization of sodium superoxide in sodium-oxygen batteries. Nat. Commun. 7, 10670–10677 (2016).

Bryantsev, V. S. et al. Predicting solvent stability in aprotic electrolyte Li–air batteries: nucleophilic substitution by the superoxide anion radical (O2−). J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 12399–12409 (2011).

Bryantsev, V. S. & Faglioni, F. Predicting autoxidation stability of ether-and amide-based electrolyte solvents for Li–air batteries. J. Phys. Chem. A 116, 7128–7138 (2012).

Bryantsev, V. S. & Blanco, M. Computational study of the mechanisms of superoxide-induced decomposition of organic carbonate-based electrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 379–383 (2011).

Xu, K. Nonaqueous liquid electrolytes for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Chem. Rev. 104, 4303–4418 (2004).

Xu, K. Electrolytes and interphases in Li-ion batteries and beyond. Chem. Rev. 114, 11503–11618 (2014).

Rupich, M., Pitts, L. & Abraham, K. Characterization of reactions and products of the discharge and forced overdischarge of Li/SO2 cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 129, 1857–1861 (1982).

Bowden, W. L., Chow, L., Demuth, D. L. & Holmes, R. W. Chemical reactions in lithium sulfur dioxide cells discharged at high rates and temperatures. J. Electrochem. Soc. 131, 229–234 (1984).

Armand, M. et al. Conjugated dicarboxylate anodes for Li-ion batteries. Nat. Mater. 8, 120–125 (2009).

Hu, Y.-S. et al. Electrochemical lithiation synthesis of nanoporous materials with superior catalytic and capacitive activity. Nat. Mater. 5, 713–717 (2006).

Hong, J. et al. Biologically inspired pteridine redox centres for rechargeable batteries. Nat. Commun. 5, 5335 (2014).

Black, R. et al. Screening for superoxide reactivity in Li-O2 batteries: effect on Li2O2/LiOH crystallization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2902–2905 (2012).

Hall, D. S., Self, J. & Dahn, J. R. Dielectric constants for quantum chemistry and Li-ion batteries: solvent blends of ethylene carbonate and ethyl methyl carbonate. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 22322–22330 (2015).

Martin, R. P. & Sawyer, D. T. Electrochemical reduction of sulfur dioxide in dimethylformamide. Inorg. Chem. 11, 2644–2647 (1972).

Lambeth, D. O. & Palmer, G. The kinetics and mechanism of reduction of electron transfer proteins and other compounds of biological interest by dithionite. J. Biol. Chem. 248, 6095–6103 (1973).

Lough, S. M. & McDonald, J. W. Synthesis of tetraethylammonium dithionite and its dissociation to the sulfur dioxide radical anion in organic solvents. Inorg. Chem. 26, 2024–2027 (1987).

Jellema, R., Bulthuis, J. & Van der Zwan, G. Dielectric relaxation of acetonitrile-water mixtures. J. Mol. Liq. 73, 179–193 (1997).

Gagliardi, L. G., Castells, C. B., Rafols, C., Rosés, M. & Bosch, E. Static dielectric constants of acetonitrile/water mixtures at different temperatures and Debye–Hückel A and a0B parameters for activity coefficients. J. Chem. Eng. Data 52, 1103–1107 (2007).

Huggins, R. A. Advanced Batteries: materials Science Aspects Springer (2008).

Ottakam Thotiyl, M. M., Freunberger, S. A., Peng, Z. & Bruce, P. G. The carbon electrode in nonaqueous Li–O2 cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 494–500 (2012).

Itkis, D. M. et al. Reactivity of carbon in lithium–oxygen battery positive electrodes. Nano Lett. 13, 4697–4701 (2013).

Syty, A. Determination of sulfur dioxide by ultraviolet absorption spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 45, 1744–1747 (1973).

Sun, S., Niu, Y., Sun, Z., Xu, Q. & Wei, X. Solubility properties and spectral characterization of sulfur dioxide in ethylene glycol derivatives. RSC Adv. 5, 8706–8712 (2015).

Ake, R. L., Oglesby, D. M. & Kilroy, W. P. A spectroscopic investigation of lithium dithionite and the discharge products of a Li/SO2 cell. J. Electrochem. Soc. 131, 968–974 (1984).

Xia, C., Black, R., Fernandes, R., Adams, B. & Nazar, L. F. The critical role of phase-transfer catalysis in aprotic sodium oxygen batteries. Nat. Chem. 7, 496–501 (2015).

Gao, X., Chen, Y., Johnson, L. & Bruce, P. G. Promoting solution phase discharge in Li-O2 batteries containing weakly solvating electrolyte solutions. Nat. Mater. 15, 882–888 (2016).

Lim, H.-D. et al. The potential for long-term operation of a lithium–oxygen battery using a non-carbonate-based electrolyte. Chem. Commun. 48, 8374–8376 (2012).

Lim, H. D. et al. Enhanced power and rechargeability of a Li−O2 battery based on a hierarchical‐fibril CNT electrode. Adv. Mater. 25, 1348–1352 (2013).

Hartmann, P. et al. A rechargeable room-temperature sodium superoxide (NaO2) battery. Nat. Mater. 12, 228–232 (2013).

Bender, C. L., Jache, B., Adelhelm, P. & Janek, J. Sodiated carbon: a reversible anode for sodium–oxygen batteries and route for the chemical synthesis of sodium superoxide (NaO2). J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 20633–20641 (2015).

Lim, H.-D. et al. Rational design of redox mediators for advanced Li–O2 batteries. Nat. Energy 1, 16066 (2016).

Liu, T. et al. Cycling Li-O2 batteries via LiOH formation and decomposition. Science 350, 530–533 (2015).

Shui, J.-L. et al. Reversibility of anodic lithium in rechargeable lithium–oxygen batteries. Nat. Commun. 4, 2255–2261 (2013).

Jang, I. C., Ida, S. & Ishihara, T. Lithium depletion and the rechargeability of Li–O2 batteries in ether and carbonate electrolytes. ChemElectroChem 2, 1380–1384 (2015).

Bieker, G., Winter, M. & Bieker, P. Electrochemical in situ investigations of SEI and dendrite formation on the lithium metal anode. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 8670–8679 (2015).

Abraham, K. & Chaudhri, S. The lithium surface film in the Li/SO2 cell. J. Electrochem. Soc. 133, 1307–1311 (1986).

Hartmann, P. et al. Pressure dynamics in metal–oxygen (metal–air) batteries: a case study on sodium superoxide cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 1461–1471 (2014).

Burke, C. M. et al. Implications of 4e− oxygen reduction via iodide redox mediation in Li–O2 batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 1, 747–756 (2016).

Hartmann, P. et al. A comprehensive study on the cell chemistry of the sodium superoxide (NaO2) battery. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 11661–11672 (2013).

Bochevarov, A. D. et al. Jaguar: a high‐performance quantum chemistry software program with strengths in life and materials sciences. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 113, 2110–2142 (2013).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle–Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Becke, A. D. Density‐functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Hariharan, P. & Pople, J. A. The effect of d-functions on molecular orbital energies for hydrocarbons. Chem. Phys. Lett. 16, 217–219 (1972).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the HMC (Hyundai Motor Company) and by Project Code (IBS-R006-G1). This work was also supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grand funded by the Korea government (MSIP; No. 2015R1A2A1A10055991).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.P. and H.-D.L designed and performed the electrochemical analyses and materials characterizations. H.-K.L. and H.K. performed the DFT calculations. W.M.S. observed the morphologies of the discharge products. S.M. conducted the lithium symmetric cell tests. Y.K., B.L. and Y.B. discussed and contributed to integrate the results. K.K. conceived the original idea, supervised the research, contributed to scientific discussions and writing of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Tables, Supplementary Note and Supplementary References (PDF 1070 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Park, H., Lim, HD., Lim, HK. et al. High-efficiency and high-power rechargeable lithium–sulfur dioxide batteries exploiting conventional carbonate-based electrolytes. Nat Commun 8, 14989 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14989

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14989

This article is cited by

-

Pathways of the Electrochemical Nitrogen Reduction Reaction: From Ammonia Synthesis to Metal-N2 Batteries

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2023)

-

MLSolvA: solvation free energy prediction from pairwise atomistic interactions by machine learning

Journal of Cheminformatics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.