Abstract

Due to their short wavelength, X-rays can in principle be focused down to a few nanometres and below. At the same time, it is this short wavelength that puts stringent requirements on X-ray optics and their metrology. Both are limited by today’s technology. In this work, we present accurate at wavelength measurements of residual aberrations of a refractive X-ray lens using ptychography to manufacture a corrective phase plate. Together with the fitted phase plate the optics shows diffraction-limited performance, generating a nearly Gaussian beam profile with a Strehl ratio above 0.8. This scheme can be applied to any other focusing optics, thus solving the X-ray optical problem at synchrotron radiation sources and X-ray free-electron lasers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modern synchrotron radiation sources and X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) provide highly brilliant X-ray beams that allow studying the structure and dynamics of matter from atomic distances and a few femtoseconds to macroscopic dimensions and seconds. Creating small and intense X-ray beams is crucial to confine the beam and concentrate the radiation onto the sample. Ideally, this would require diffraction-limited X-ray optics with high numerical aperture (NA) that are at the same time stable in the intense XFEL pulses1. So far, mainly mirror systems2,3 and beryllium compound refractive lenses4,5 (Be CRLs) are in routine operation at XFELs.

Due to the short wavelength of X-rays, the fabrication of X-ray optics requires the most advanced technologies, such as lithographic nanofabrication for diffractive6 and refractive optics7, surface figuring with atomic precision for total reflection and multilayer mirrors8,9 and thin-film technologies for multilayer optics10. Today, most X-ray optics are limited by fabrication limitations, and tradeoffs need to be made in terms of aberration-free performance and highest possible NA.

To characterize the optics and the resulting nanobeams, metrology has become more and more demanding. Over the past years, X-ray scanning coherent diffraction microscopy, also known as ptychography11, has evolved to one of the most important methods for X-ray beam and optics characterization12. It can be used to quantitatively retrieve the complex wavefield of a focused X-ray beam and, hence, reveals wavefront errors with unprecedented sensitivity and spatial resolution13,14. From the three-dimensional reconstruction of the focal spot volume4, detailed information about aberrations of the optical system can be deduced15,16.

Here, we present a general scheme to assess aberrations of an X-ray optical system under working conditions and correct them by introducing an appropriate X-ray phase plate into the optical path to achieve diffraction-limited focusing. The phase plate operates in transmission and is based on refraction. Hence, it is largely insensitive to small shape and surface inaccuracies of a few μm and can correct residual aberrations originating from surface errors of reflective optics, zone deformations in diffractive optics and accumulated surface errors in larger refractive lens stacks. Using ptychography, we measured the complex wavefield of a focused X-ray beam generated by Be CRLs at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). The detailed knowledge of the complex wavefield was used to fabricate a corrective phase plate that compensates for the aberrations and thus creates a diffraction-limited focus when introduced into the beam following the lens. The method can be applied very generally to solve the X-ray focusing problem at synchrotron radiation sources and XFELs and will affect fields as diverse as X-ray microscopy and high-resolution imaging17,18, serial crystallography19,20, creating matter in extreme conditions21, nonlinear X-ray optics22 and single-molecule imaging23.

Results

Initial aberration analysis

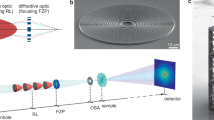

At the Matter in Extreme Conditions (MEC) endstation24 of the LCLS, focused X-ray pulses are, for example, used for magnified phase-contrast imaging of shock waves in matter18, to locally probe the structure in shocked matter by diffraction or to generate high-energy-density states in matter. For this purpose, the LCLS beam is focused slightly before or at the sample position, respectively, using refractive X-ray lenses. In our experiment, 20 refractive lenses made of beryllium were used to focus the beam (photon energy: E=8.2 keV) with a focal length of ∼250 mm (Fig. 1). It was characterized in detail by ptychography with a test object placed slightly out of focus (Fig. 1a) and showed pronounced spherical aberration4 that was also confirmed by the Ronchi test25,26 (Fig. 1b). By propagating the wavefield back to the exit plane of the lens and subtracting a spherical wave corresponding to the focal distance, a detailed map of the phase errors, which are responsible for the aberrations in the focus, was determined quantitatively (Fig. 2a). The measured wavefront deviation was used to model the shape error of individual lens surfaces (see optics characterization in the Methods). It was found that shape inaccuracies smaller than 500 nm per lens surface (Fig. 2c) reproduce the measured wavefront deviation shown in Fig. 2a very accurately as depicted in Fig. 2b with the standard deviation of 0.3 rad between the two. A reduction of phase errors in individual refractive lenses is technically extremely challenging, as the shape errors for individual lens surfaces lie in the range of the current fabrication tolerances. Therefore, we pursued the following approach: the resulting accumulated phase error of the whole lens stack was corrected for by a single phase plate placed after the stack (Fig. 1). It was made out of an amorphous SiO2 substrate by ultrashort-pulse laser ablation27. The material was chosen based on its radiation hardness and well-known fabrication parameters for laser micromachining28. The phase plate was locally structured in thickness such as to add an additional phase shift that compensates the measured residual phase error of the whole lens (see phase plate design and fabrication in the Methods). The modelled wavefront deformation (Fig. 2b) defines the shape of the phase plate as shown in Fig. 2d,e.

X-rays with E=8.2 keV (selected by a Si-111 monochromator) were focused by a compound refractive lens made of beryllium (Be CRL). To correct for the residual aberrations of the lens, a phase plate was installed immediately following the lens stack. (a) For ptychography the test object—an array of Siemens stars—was placed in the vicinity of the focal plane. The sample was scanned transversely to the beam (x–y raster scan) and far-field diffraction patterns were recorded at each position. (b) Ronchigrams were recorded using a grating test sample with a distinct grating period positioned along the optical axis. Further details can be found in the Methods.

(a) Measured wavefront deformation at the lens exit compared to a spherical wave. (b) Phase error of a modelled lens stack at the lens exit. Scale bars in a,b correspond to 50 μm. (c) Deformation of every lens surface in the modelled stack of 20 beryllium compound refractive lenses used to generate b. The surface error (solid red line) is enhanced by the axis on the right side. (d) Model of the SiO2 phase plate to correct for errors shown in a–c. (e) Surface profile of the manufactured corrective SiO2 phase plate using ultrashort-pulse laser ablation compared with the design goal d as measured by a laser scanning microscope.

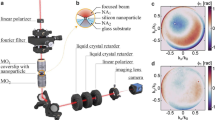

Diffraction-limited X-ray focusing

By introducing the phase plate as an additional optical component behind the lens stack, the X-ray focus has been significantly improved. The performance of the corrected focusing optics was investigated at the LCLS, and was also confirmed in different experiments at the synchrotron radiation sources PETRA III (DESY, Hamburg, Germany) and Diamond Light Source (DLS) (Oxfordshire, UK). For comparison, the optics were characterized with and without the corrective phase plate by ptychography and the Ronchi test. Figure 3a–c show the results without the corrective phase plate measured at LCLS: the caustic (Fig. 3a) showed a clear signature of spherical aberration, where the paraxial rays are focused to a point upstream of the focus for the peripheral rays. In the focal plane (dashed line in Fig. 3a), defined as the plane with highest peak intensity, the side lobes around the central focal speckle were strongly pronounced (Fig. 3b). The spherical aberration was confirmed by the Ronchi test that showed distorted interference fringes characteristic of spherical aberration (Fig. 3c). The associated root meansquare (r.m.s.) wavefront error in the exit pupil of the optics was 0.23 λ.

(a) Beam caustic retrieved from the ptychographic reconstruction. Scale bars are 2 μm and 1 mm in x and z direction, respectively. (b) Logarithmic intensity distribution in the focal plane as marked by the dashed line in a. Scale bar represents 2 μm in x and y direction. (c) Ronchigram recorded at the dotted position in the beam caustic a. Insets a–c are without the phase plate. (d) Beam caustic retrieved from the ptychographic reconstruction. Scale bars identical to a. (e) Logarithmic intensity distribution in the focal plane as marked by the dashed line in d. Scale bar identical to b. (f) Ronchigram recorded at the dotted position in the beam caustic d. Insets d–f are with the phase plate installed. Insets a,b,d,e share the same colour bar as well as c,f.

Results for the optics with the corrective phase plate obtained at LCLS are shown in Fig. 3d–f: the caustic showed a nearly Gaussian focus (Fig. 3d), and the side lobes in the focal plane were significantly reduced (Fig. 3e). In addition, the Ronchigram showed almost undistorted straight lines (Fig. 3f), which are characteristic of an aberration-free focus. Wavefront errors in the exit pupil were reduced down to 0.06 λ r.m.s. The focal properties for these measurements are analysed in more detail in Fig. 4a. The relative intensity of the side lobes decreased by an order of magnitude for the corrected lens (dotted blue line) versus the aberrated one (solid green line). Compared with a perfect focus created by a completely aberration-free lens (dashed red line), the side lobes of the corrected focus were only larger by a factor of two. Figure 4b shows the radially integrated relative flux as a function of position from the optical axis. For the corrected optics, ∼75% of the integral flux was within the central speckle covering an area with a 125 nm radius. On the other hand, the uncorrected focus only concentrated ∼25% of the flux in the central speckle, distributing ∼75% of the radiation over an area with an 800 nm radius. In all experiments the relative flux in the central speckle increased from 0.23(6) to ∼0.80(6) as compared with the focus of an aberration-free ideal lens. For the corrected lens, the Strehl ratio, that is the ratio of the maximal intensity in the focus compared with that of ideal optics, improved from 0.29(7) to 0.87(5) for all experiments and is thus larger than 0.8, above which an optical system is typically considered as diffraction limited29. In comparison to that, the lateral full-width at half-maximum beam size was almost unchanged. We determined 156(3) nm and 151(3) nm for the corrected and uncorrected focus, respectively, which is only slightly larger than that of the ideal focus of 143(1) nm.

(a) Horizontal slice (x-direction, logarithmic scale) through the focal plane depicted in Fig. 3b,e and for an ideal lens. (b) Radially integrated intensity distribution around the centre of the focal spot. The solid green line represents the results for the uncorrected lens (without the phase plate), the dotted blue line represents the phase plate corrected lens, and the dashed red line represents the modelled aberration-free lens in both a,b.

Discussion

In conclusion, we successfully demonstrated the correction of residual spherical aberration in a stack of Be CRLs by a corrective phase plate, thus achieving diffraction-limited focusing with a Strehl ratio of 0.87(5). Minimizing the intensity in the outer lobes is not only critical for high power density experiments, but also for scanning microscopy applications, as side lobes may contribute significantly to the measured signals. The approach provides a versatile and general solution to correct aberrations for a variety of X-ray optics ranging from refractive optics as demonstrated here, diffractive optics such as Fresnel zone plates and multilayer Laue lenses, as well as reflective mirror optics. All these optics may be corrected to improve their performance beyond current manufacturing limitations. This effectively solves the problem of aberrations and of technological limitations in the fabrication of optics in the hard X-ray regime. Therefore, X-ray phase plates could become an essential technology for the next generation of XFEL and storage ring sources. Diffraction-limited X-ray foci of nm size are not only crucial to improve existing experiments, but they might also enable novel science opportunities such as nonlinear Compton scattering30 or pair creation by photon–photon scattering31.

Methods

Experimental setup

The experiments were conducted at three different facilities (MEC endstation at the LCLS, beamline P06 at PETRA III and beamline I13-1 at DLS) with similar experimental setups. The broadband X-ray radiation was monochromatized by silicon crystals to a photon energy of E=8.2 keV. The flat beam was focused by a set of 20 Be CRLs with a radius of curvature of R=50 μm and geometrical aperture of D=300 μm. The aperture was defined by a pinhole of D=300 μm diameter that matches the geometrical aperture at the entrance of the optics. The phase plate was mounted directly behind the CRL, either in a self-centring special mount or in a motorized mount adjustable in x and y to investigate tolerable lateral misalignment and to optimize the centring of the phase plate. For the ptychographic scans, an array of small Siemens stars with 50 nm smallest features structured in 1 μm thick tungsten on a diamond substrate was placed into the vicinity of the focal plane (Fig. 1a). The far-field diffraction patterns were recorded using an area detector placed several metres behind the test object (LCLS: in-air CS-PAD 140k at a distance 4.8 m downstream of the sample, DLS: Medipix-3-based Merlin detector at 2.6 m downstream of the sample, PETRA III: Medipix-3-based LAMBDA (Large Area Medipix-Based Detector Array) detector at 2.2 m downstream of the sample). For the Ronchi test (Fig. 1b) we used a high-resolution X-ray camera magnifying a scintillator screen and gratings with 270 nm period structured into 1 μm thick tungsten on a diamond substrate.

Optics characterization

The recorded far-field diffraction patterns were processed with a ptychographic algorithm (ePIE)32 with position refinement4 to reconstruct both the complex object transmission function of the test sample, as well as the complex-valued wavefield Ψ that illuminated the sample. From the illumination and using the Fresnel–Kirchhoff diffraction integral33, the complex wavefield can be calculated at any point along the optical axis, creating a beam caustic as shown in Fig. 3. We propagated Ψ back to the lens exit to obtain Ψexit(x, y). To reveal phase errors, we subtracted the phase of a spherical wave  with radius Δz=zf−zexit that was matched to the distance from lens exit zexit to focal plane zf of the Be CRL34:

with radius Δz=zf−zexit that was matched to the distance from lens exit zexit to focal plane zf of the Be CRL34:

Residual deviations from a plane phase represent the aberrations present in the given optics (Fig. 2a) and can be evaluated to accurately model their shape error (Fig. 2c) and to design corrective elements like the phase plate characterized in Fig. 2d,e. To model the error of a single lens surface, we propagated a plane wave from lens to lens through the stack, treating every lens as thin. Under the assumption of an identical deformation for every lens and radial symmetry, the shape was iteratively refined until the total phase deviation shown in Fig. 2b matched the measured one in Fig. 2a (σ≈0.3 rad).

In addition, an independent Ronchi test was carried out as depicted in Fig. 1b. Here, a diffraction grating was placed in the vicinity of the focal plane. The grating period was chosen so that the diffracted beam cones overlap each other roughly half way (see Fig. 1b and Ronchigrams in Fig. 3c,f). The interfering amplitudes from the cones created a distinct fringe pattern. Straight interference fringes indicate an aberration-free system (Fig. 3f), and bent lines can reveal coma, astigmatism or, in our case, spherical aberration (Fig. 3c) on a single-shot basis25. Thus, Ronchi patterns were used to align the lens and the phase plate to one another.

Phase plate design and fabrication

From the reconstructed wavefront deviation  a phase plate shape zPP(x, y) can be designed, so that the induced phase shift in the material

a phase plate shape zPP(x, y) can be designed, so that the induced phase shift in the material  compensates any present wavefront deviations:

compensates any present wavefront deviations:

The phase plate structure was created in an amorphous SiO2 substrate (Vitreosil 077, ρ=2.2 g cm−3) with a thickness of 118(2) μm.

We used an ultrashort-pulsed laser system (Trumpf TruMicro 5050) to enable nonlinear absorption in the focal region for highly localized energy transfer27,28. The laser emits pulses with durations of 8 ps at a wavelength of 1030, nm. The pulse energy was set to 0.2 μJ to facilitate precise ablation of the desired structure. Furthermore, a microscope objective with a NA of 0.4 served to focus the pulses onto the substrate, providing a spot size of ∼1 μm. The sample was moved underneath the focus using a nanopositioning system. Based on the computed surface profile of the phase plate, individual layers with a thickness of ∼1 μm were sequentially ablated.

The phase plate has a transmission of ∼54%. It can be increased up to 95% if the thickness of the supporting SiO2 substrate is minimized, yielding diffraction-limited and highly efficient X-ray optics. The system is applicable over a large photon energy range when correcting refractive optics, as the refractive power is nearly material independent far from absorption edges. Thus, a single phase plate can correct aberrations of a refractive lens over a large photon energy range.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Seiboth, F. et al. Perfect X-ray focusing via fitting corrective glasses to aberrated optics. Nat. Commun. 8, 14623 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14623 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

David, C. et al. Nanofocusing of hard X-ray free electron laser pulses using diamond based Fresnel zone plates. Sci. Rep. 1, 57 (2011).

Yumoto, H. et al. Focusing of X-ray free-electron laser pulses with reflective optics. Nat. Photon. 7, 43–47 (2013).

Mimura, H. et al. Generation of 1020 W cm−2 hard X-ray laser pulses with two-stage reflective focusing system. Nat. Commun. 5, 3539 (2014).

Schropp, A. et al. Full spatial characterization of a nanofocused x-ray free-electron laser beam by ptychographic imaging. Sci. Rep. 3, 01633 (2013).

Seiboth, F. et al. Focusing XFEL SASE pulses by rotationally parabolic refractive x-ray lenses. J. Phys. 499, 012004 (2014).

Vila-Comamala, J. et al. Ultra-high resolution zone-doubled diffractive X-ray optics for the multi-keV regime. Opt. Express 19, 175–184 (2011).

Schroer, C. G. et al. Hard x-ray nanoprobe based on refractive x-ray lenses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 124103 (2005).

Mimura, H. et al. Efficient focusing of hard x rays to 25 nm by a total reflection mirror. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 051903 (2007).

Mimura, H. et al. Breaking the 10 nm barrier in hard-X-ray focusing. Nat. Phys. 6, 122–125 (2010).

Morgan, A. J. et al. High numerical aperture multilayer Laue lenses. Sci. Rep. 5, 9892 (2015).

Thibault, P. et al. High-resolution scanning X-ray diffraction microscopy. Science 321, 379–382 (2008).

Schropp, A. et al. Hard x-ray nanobeam characterization by coherent diffraction microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 091102 (2010).

Kewish, C. M. et al. Ptychographic characterization of the wavefield in the focus of reflective hard X-ray optics. Ultramicroscopy 110, 325–329 (2010).

Hönig, S. et al. Full optical characterization of coherent x-ray nanobeams by ptychographic imaging. Opt. Express 19, 16324–16329 (2011).

Kewish, C. M. et al. Reconstruction of an astigmatic hard X-ray beam and alignment of K-B mirrors from ptychographic coherent diffraction data. Opt. Express 18, 23420–23427 (2010).

Vila-Comamala, J. et al. Characterization of high-resolution diffractive X-ray optics by ptychographic coherent diffractive imaging. Opt. Express 19, 21333–21344 (2011).

Schroer, C. G. et al. Coherent x-ray diffraction imaging with nanofocused illumination. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 090801 (2008).

Schropp, A. et al. Imaging shock waves in diamond with both high temporal and spatial resolution at an XFEL. Sci. Rep. 5, 11089 (2015).

Chapman, H. N. et al. Femtosecond X-ray protein nanocrystallography. Nature 470, 73–77 (2011).

Ayyer, K. et al. Macromolecular diffractive imaging using imperfect crystals. Nature 530, 202–206 (2016).

Nagler, B. et al. Turning solid aluminium transparent by intense soft X-ray photoionization. Nat. Phys. 5, 693–696 (2009).

Glover, T. E. et al. X-ray and optical wave mixing. Nature 488, 603–608 (2012).

Neutze, R., Wouts, R., van der Spoel, D., Weckert, E. & Hajdu, J. Potential for biomolecular imaging with femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature 406, 752–757 (2000).

Nagler, B. et al. The Matter in Extreme Conditions instrument at the Linac Coherent Light Source. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 22, 520–525 (2015).

Nilsson, D. et al. Ronchi test for characterization of nanofocusing optics at a hard x-ray free-electron laser. Opt. Lett. 37, 5046–5048 (2012).

Uhlén, F. et al. Ronchi test for characterization of X-ray nanofocusing optics and beamlines. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 21, 1105–1109 (2014).

Chichkov, B. N., Momma, C., Nolte, S., von Alvensleben, F. & Tünnermann, A. Femtosecond, picosecond and nanosecond laser ablation of solids. Appl. Phys. A 63, 109–115 (1996).

Joglekar, A. et al. A study of the deterministic character of optical damage by femtosecond laser pulses and applications to nanomachining. Appl. Phys. B 77, 25–30 (2003).

van den Bos, A. Aberration and the strehl ratio. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 17, 356–358 (2000).

Hartemann, F. V. & Kerman, A. K. Classical theory of nonlinear compton scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 624–627 (1996).

Breit, G. & Wheeler, J. A. Collision of two light quanta. Phys. Rev. 46, 1087–1091 (1934).

Maiden, A. M. & Rodenburg, J. M. An improved ptychographical phase retrieval algorithm for diffractive imaging. Ultramicroscopy 109, 1256–1262 (2009).

Born, M. & Wolf, E. Principles of Optics Pergamon Press (1980).

Seiboth, F. et al. Quantitative characterization of aberrations in x-ray optics. Proc. SPIE 9963, 99630P (2016).

Acknowledgements

Parts of this research were carried out at the coherence branch of beamline I13 at Diamond Light Source (DLS) and beamline P06 at PETRA III at DESY, a member of the Helmholtz Association (HGF). Use of the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The MEC instrument is supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Fusion Energy Sciences under Contract No. SF00515. This work is supported by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under Grant Number 05K13OD2, the DFG under Grant SCHR 1137/1-1 and the Swedish Research Council. F.S., A.S. and C.Rö. acknowledge the Peter Paul Ewald fellowship from the Volkswagen Foundation. We thank Robert Hoppe for providing and maintaining the GPU-enhanced ptychographic engine and Dirk Samberg for his technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.S., A.S. and C.G.S. conceived and coordinated the experiments. The experiments at LCLS were performed by F.S., A.S., E.C.G., H.J.L., B.N. and C.G.S. The samples were fabricated by J.R., K.P., S.G. and U.V. The phase plate production was conceived and coordinated by F.S. and C.Rö. The phase plates were manufactured by T.U., M.W. and S.N. The experiment at DLS was performed by F.S., F.W., J.R., K.P., S.G., U.V., U.W. and C.Ra. The experiment at PETRA III was performed by F.S., M.S., U.B., J.G. and G.F. The data were analysed by F.S. The manuscript was written by F.S., A.S. and C.G.S. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Seiboth, F., Schropp, A., Scholz, M. et al. Perfect X-ray focusing via fitting corrective glasses to aberrated optics. Nat Commun 8, 14623 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14623

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14623

This article is cited by

-

Ultracompact mirror device for forming 20-nm achromatic soft-X-ray focus toward multimodal and multicolor nanoanalyses

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Direct high-resolution X-ray imaging exploiting pseudorandomness

Light: Science & Applications (2023)

-

Materials under extreme conditions using large X-ray facilities

Nature Reviews Methods Primers (2023)

-

Alvarez varifocal X-ray lens

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Direct Laser Writing of Microscale 3D Structures: Morphological and Mechanical Properties

Journal of Russian Laser Research (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.