Abstract

Phase transitions, where observable properties of a many-body system change discontinuously, can occur in both open and closed systems. By placing cold atoms in optical cavities and inducing strong coupling between light and excitations of the atoms, one can experimentally study phase transitions of open quantum systems. Here we observe and study a non-equilibrium phase transition, the condensation of supermode-density-wave polaritons. These polaritons are formed from a superposition of cavity photon eigenmodes (a supermode), coupled to atomic density waves of a quantum gas. As the cavity supports multiple photon spatial modes and because the light–matter coupling can be comparable to the energy splitting of these modes, the composition of the supermode polariton is changed by the light–matter coupling on condensation. By demonstrating the ability to observe and understand density-wave-polariton condensation in the few-mode-degenerate cavity regime, our results show the potential to study similar questions in fully multimode cavities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultracold atoms have provided an exemplary model system to demonstrate the physics of closed-system, equilibrium phase transitions, confirming many theoretical models and results1. A striking manifestation of the role quantum mechanics can play in the physics of equilibrium phase transitions is the well-known Bose–Einstein condensation (BEC) of bosonic particles at low temperatures into a single, macroscopically populated quantum wave. Our understanding of dissipative phase transitions in quantum systems is less developed and experiments that probe this physics even less so. For example, condensation in quantum systems out of thermal equilibrium is far less understood than in equilibrium2,3, yet becoming experimentally relevant, especially via the study of polariton condensates: when matter couples strongly to light, new collective modes called polaritons arise. Condensation of these quasiparticles has been actively studied in the form of exciton polaritons4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11.

With only a single mode of light coupled to the BEC, self-organization has been observed, but is uniquely defined by cavity geometry alone and is best described as a density-wave (DW) polariton condensate12,13,14. In contrast, for exciton polaritons, complex pattern formation8,9,10 has been seen, arising from the existence of many nearly degenerate modes in planar microcavities. In addition, related physics has also been observed in systems in which no DW-polariton condensation occurs: for example, superradiant emission using hyperfine states15, supermode emission without self-organization16 and self-organization without a cavity17. The Bose–Hubbard model with infinite-range interactions has been studied18,19. We note that condensation of DW polaritons is quite distinct from lasing: standard lasing requires inversion of the gain medium, is driven by an incoherent pump and is generally incompatible with strong light–matter coupling, whereas the transition we study differs on all of these points.

We report a step towards the observation of an unusual form of non-equilibrium condensation, a ‘supermode-DW-polariton’ condensate. Here, supermode refers to the eigenmode built as a superposition of the bare cavity modes20. The supermode-polariton dressed state is dependent on the pump-cavity detuning Δc and on the overlap of the bare-cavity modes with the BEC position and shape. The matter component is an atomic DW excitation rather than the electronic excitation of exciton-polariton condensates. It is important to distinguish the condensation of supermode DW polaritons from condensation of the atoms; for example, self-consistent formation of atomic DWs and cavity light can be studied with thermal atoms21,22 and with BECs12. However, some of the signatures we demonstrate, such as the atomic structure factor, are observable only with BECs of atoms in multimode cavities (see Methods for further discussion). By embedding the exquisite control available for ultracold atoms within multimode quantum-optical systems, our experiment opens avenues for experimentally studying quantum fluctuation-driven transitions and quantum criticality2,23,24,25. In such a system, one can expect physics beyond mean-field theories such as a quantum Brazovskii transition or a short-range spin glass23,26. Thus, these systems will provide experimental access to non-trivial phase transitions in driven dissipative quantum systems2,3,23,24,27 and enabling the studies of exotic non-equilibrium spin glasses and neuromorphic computation26,28.

Results

Supermode DW polaritons

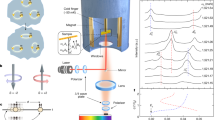

In the work reported here, we see how with a few modes coupled to the BEC (see Fig. 1b,c) the supermode-DW-polariton condensate arises in a regime intermediate between BECs coupled to a single-mode cavity and those coupled to a confocal or concentric cavity supporting many hundreds of degenerate modes. When the atoms are pumped with a laser orthogonal to the cavity axis (see Fig. 1a), the normal modes of the atom-cavity system evolve to become supermode DW polaritons, new superpositions of supermodes mixed by the DW fluctuations of the atoms. Above a critical pump threshold, we see defining characteristics of supermode-DW-polariton condensates, heralded by three observables as follows: first, superradiant emission of light from the cavity with the spatial pattern of one of these new supermodes; second, Z2 symmetry breaking of the phase of the cavity field, locking to either  or

or  +π with respect to the pump phase; and third, organization of the BEC wavefunction into one of two checkerboard lattice configurations—each corresponding to a specific phase of the cavity field. Such observables have been seen in single-mode cavities12. In addition, we see how non-trivial transverse spatial structure of the supermode can result in lattice defects (matter–wave phase slips): these are seen in the structure factor in an atomic time-of-flight measurement. Observations of all these defining characteristics are presented.

+π with respect to the pump phase; and third, organization of the BEC wavefunction into one of two checkerboard lattice configurations—each corresponding to a specific phase of the cavity field. Such observables have been seen in single-mode cavities12. In addition, we see how non-trivial transverse spatial structure of the supermode can result in lattice defects (matter–wave phase slips): these are seen in the structure factor in an atomic time-of-flight measurement. Observations of all these defining characteristics are presented.

(a) The 87Rb BEC is trapped at the centre of the cavity and at the focus of the standing wave transverse pump far detuned from electronic transitions. (ODT lasers not shown.) Detection channels include absorption imaging of atomic density and detection of cavity emission using either a single-photon counter, a photodetector or an electron-multiplying CCD camera (shown). (b,c) Cavity transmission showing near-degenerate bare-cavity mode families (that is, modes with l+m=const.) versus frequency. These are measured with a longitudinal probe (not shown) in the near-confocal regime for (b) even modes and (c) odd modes. (d) Superradiant emission in the transverse electromagnetic l=m=0 (TEM00) mode when pumped above DW polariton condensation threshold at position d in b. (e–j) Superradiant photonic components of various supermode-DW-polariton condensates of the l+m=6 family. The colourbar scale for cavity emission in d–j is to the right of j. For all d–j, the axes and scale are indicated with the labelled arrows and the white bar as in d, where the bar equals twice the TEM00 optical waist 2w0=70 μm at the BEC.

The near-confocal optical cavity employed here supports families of optical modes that each lie within a small frequency bandwidth, as shown in Fig. 1b,c (see Methods). One can observe the superradiant emission of various supermode-DW-polariton condensates by pumping at different Δc tuned near or within a mode family, as can be seen in Fig. 1e,j. This is in contrast to the DW-polariton condensate of a single-mode cavity such as shown in Fig. 1d: This is not a supermode no matter the detuning Δc near this isolated Gaussian mode. The supermodes in Fig. 1e–j, differ from ideal Hermite–Gaussian modes due to three factors as follows: first, the bare cavity modes are themselves mixtures of ideal Hermite–Gaussian modes (due to mirror aberrations mixing modes when there is spectral overlap of modes near degeneracy)29; second, these bare cavity modes are mixed by the dielectric atomic medium to form supermode polaritons; and third, these dressed states are remixed by the emergent DW to form new supermodes above the polariton condensation threshold.

Decomposition of photonic components

Figure 2 illustrates how remixed photonic components of the supermode-DW-polariton condensate can differ from the supermode-polariton dressed states. The three bare cavity modes of the l+m=2 family are mixed by a BEC at the cavity centre to produce the three supermode peaks. The photonic component, shown in Fig. 2h–l, of the supermode-DW-polariton condensates can differ from that of the supermode polaritons in Fig. 2c–g due to new supermode mixing by the macroscopically populated atomic DW above threshold. This is most pronounced away from resonance: see, for example, how Fig. 2c,h differ; the supermode-DW-polariton condensate at 46 MHz (Fig. 2h) is ∼81% TEM02 and 19% TEM20, whereas the associated below-threshold supermode polariton (Fig. 2c) is ∼52% TEM02, 9% TEM20 and 39% TEM11. The suppression of the TEM11 component above threshold can be understood as resulting from its poor overlap with the BEC and thus weaker mixing with the DW mode. A similar remixing of supermodes occurs on the blue-detuned side at 56 MHz.

(a) Mode spectrum without atoms (blue) and with atoms (red) of the l+m=2 family versus frequency measured on a single-photon counter with a longitudinal probe. Frequency scale relative to TEM00 mode in Fig. 1b. The three supermode peaks of the spectrum with atoms exhibit a red dispersive shift (see Methods). Images of cavity transmission at the three bare cavity mode peaks (no atoms present) are shown in b. The asterisks in the mode labels  indicate that these bare cavity modes are not quite ideal TEM modes due to small intrafamily mode mixing by mirror aberrations. The

indicate that these bare cavity modes are not quite ideal TEM modes due to small intrafamily mode mixing by mirror aberrations. The  is unshifted due to poor overlap with centrally trapped BEC. (c–g) Images of the photonic component of the supermode-polariton dressed states and (h–l) supermode-DW-polariton condensate (pump above threshold) versus transverse-probe frequency. The photonic composition of the near-resonance supermode DW polaritons i–k corresponds closely to that of the resonant supermodes e,f. However, the supermode-DW condensates away from resonance, h and l, significantly differ from the supermodes away from resonance, c and g, demonstrating the remixing of supermodes due to DW–supermode coupling above threshold. (m) Admixture versus frequency of ideal cavity modes in the supermode-DW-polariton condensates (solid points) and the supermode polaritons (open points). Error bars represent 1 s.e. Solid lines are predicted supermode-DW-polariton condensate compositions. The colourbar for cavity emission in b is shown to the right of the rightmost subfigure. The colourbar for c–i is to the right of g,i. For all b–l, the axes and scale are indicated with the labelled arrows and the white bar as in b, where the bar equals twice the TEM00 optical waist 2w0=70 μm at the BEC.

is unshifted due to poor overlap with centrally trapped BEC. (c–g) Images of the photonic component of the supermode-polariton dressed states and (h–l) supermode-DW-polariton condensate (pump above threshold) versus transverse-probe frequency. The photonic composition of the near-resonance supermode DW polaritons i–k corresponds closely to that of the resonant supermodes e,f. However, the supermode-DW condensates away from resonance, h and l, significantly differ from the supermodes away from resonance, c and g, demonstrating the remixing of supermodes due to DW–supermode coupling above threshold. (m) Admixture versus frequency of ideal cavity modes in the supermode-DW-polariton condensates (solid points) and the supermode polaritons (open points). Error bars represent 1 s.e. Solid lines are predicted supermode-DW-polariton condensate compositions. The colourbar for cavity emission in b is shown to the right of the rightmost subfigure. The colourbar for c–i is to the right of g,i. For all b–l, the axes and scale are indicated with the labelled arrows and the white bar as in b, where the bar equals twice the TEM00 optical waist 2w0=70 μm at the BEC.

The components closely follow the theory prediction based on a linear stability analysis for mode content at condensation threshold, except near the  mode. We believe this discrepancy is due to dynamical effects not captured by this static stability analysis. See Fig. 8 in Methods for discussion.

mode. We believe this discrepancy is due to dynamical effects not captured by this static stability analysis. See Fig. 8 in Methods for discussion.

Position dependence

For the limit we consider, where the atomic cloud is smaller than the beam waist, the position of the BEC with respect to the bare-cavity modes strongly affects the photonic mode composition of the supermode-DW-polariton condensate. That is, the near-degeneracy of the bare cavity modes means that the particular supermode selected is determined by overlap with the cloud. This is easily observed by moving the BEC within the transverse plane of the cavity with the pump tuned near the l+m=1 family (see Fig. 3). We pump the system with the BEC trapped by the optical dipole trap (ODT) at each of the four intracavity positions illustrated in Fig. 3a. With the BEC trapped near either the antinode of the TEM10 or the TEM01 mode, we observe superradiant emission with a spatial pattern nearly identical to these bare-cavity modes, as shown in Fig. 3c,d. However, a BEC at the intersection between the two modes’ antinodal lobes (Fig. 3b) yields an emitted spatial pattern at 45° to the bare cavity mode axes. The threshold for organization is the same for a BEC at a bare-cavity antinode or between the antinodes, demonstrating that the BEC has mixed these bare modes equally and has created a basis for supermode DW polaritons that are rotated 45° from the original l+m=1 family eigenbasis; see Methods.

(a) Schematic of the cavity transverse plane with the bare cavity TEM01 and TEM10 modes in blue and green, respectively. Letters indicate positions of the ODT confining the BEC, whose width is much smaller than cavity mode waist (see Methods). (b–e) Moving the BEC from positions b through d changes the supermode-DW-polariton condensate composition, as may be seen by the superradiant emission in the correspondingly numbered panels. Images taken for same above-threshold pump power and detuning Δc=−30 MHz. The astigmatic splitting of the two modes is much smaller, 2.4 MHz. Position e coincides with the l+m=1 family node: poor overlap lowers the coupling and threshold is not reached for this power. The colourbar for cavity emission in b–e is to the right of c. For all b–e, the axes and scale are indicated with the labeled arrows and the white bar as in d, where the bar equals twice the TEM00 optical waist 2w0=70 μm at the BEC.

Structure factor

To complete the description of this non-equilibrium condensate, we report that observations of the momentum distribution in time-of-flight reveal the influence of the supermode structure on the matter wave component of the polariton condensate. For single-mode cavities pumped near the TEM00 mode, the atoms organize in one of two possible checkerboard patterns. However, organization in cavities supporting higher-order modes is more complicated. As illustrated in Fig. 4a versus Fig. 4b when the BEC overlaps with a node of the cavity mode, the effective DW—cavity mode coupling changes sign across the node, because the DW couples to the interference between pump field and cavity mode. This results in an organized state with a plane defect in the checkerboard lattice: that is, a π phase slip, and we confirm this configuration to be the optimal organized state via open-system simulations of the pumped BEC-cavity system. See Fig. 4d and Methods.

(a–h) Simulation of BEC organization (see Methods). Sketch of BEC (red) at the centre of (a) TEM00 or (b) TEM01 modes (blue). Calculated atomic density distribution shown in situ in c–e and after time-of-flight expansion in f–h. (a) A BEC coupled to the antinode of a field organizes into a defectless checkerboard lattice above threshold (shown in c), exhibiting a featureless structure factor in the experimentally observed Bragg peaks shown in the time-of-flight image data in i (similar to the theory calculation in f). The associated cavity emission in the TEM00 mode is shown in l. (These manifestations of DW-polariton condensation are not observable in thermal gases.) (b) By contrast, BECs located at a field node—here that of a TEM01 mode—self-organize into a checkerboard lattice with a line defect at the optical node interface, shown in d. (g) This introduces a non-trivial atomic structure factor manifest as a node in the first-order Bragg peaks of the momentum distribution. (j) Indeed, these nodes are clear in the time-of-flight atomic density image data for condensation into the primarily TEM01 mode, seen in the cavity emission data of m. The atomic density image data in k shows that the zero-order peak can develop structure if the system is driven with a higher pump power, as simulated in e,h for in-situ and time-of-flight, respectively. This increases the coupling nonlinearity, deepening the optical potential and changing the BEC wavefunction via multiple Bragg scattering events. The colourbar for c–k is shown to the right of j. The colourbar for cavity emission in l,m is to the right of l. For all c–k, the axes are indicated with labelled arrows in c,f,i for the atomic density and in l for cavity emission. The white scale bars equal c, λ=780 nm; f,i, the recoil wavevector kr=2π/λ; and l, twice the TEM00 optical waist 2w0=70 μm at the BEC.

Time-of-flight expansion of the atoms yields the atomic momentum distribution and the lattice defect appears as a node in the (ky, kz)=(±1, ±1)kr Bragg peaks of the expanding BEC’s interference pattern; see simulation in Fig. 4g. The node may be understood as a structure factor resulting from the low-momentum modulation of the organized atomic wavefunction caused by coupling to the transverse nodal structure of the supermode. The observability of a structure factor in the momentum distribution of BECs organized in orthogonally oriented and higher-order modes is shown in Fig. 5.

(a–c) Images of cavity emission of photonic components of a supermode-DW-polariton condensate for modes (a) TEM10; (b)  , which is TEM11 with only a few per cent admixture of TEM02 and TEM20; and (c) TEMα02+β20, with α≈81% and β≈19%. (d,e) Atomic density in time-of-flight for BECs coupled to the higher modes shown in a–c, respectively. (a,d) The nodal structure factor is not apparent for this mode, TEM10, which is orthogonal to the TEM01 mode shown in Fig. 4l, because for imaging along

, which is TEM11 with only a few per cent admixture of TEM02 and TEM20; and (c) TEMα02+β20, with α≈81% and β≈19%. (d,e) Atomic density in time-of-flight for BECs coupled to the higher modes shown in a–c, respectively. (a,d) The nodal structure factor is not apparent for this mode, TEM10, which is orthogonal to the TEM01 mode shown in Fig. 4l, because for imaging along  , the node in atomic density along

, the node in atomic density along  is obscured by the column integration inherent in the absorption imaging process. (b,e) A nodal structure factor is evident in the first-order Bragg peaks for this even-parity supermode-DW-polariton condensate, because the BEC sits at a cavity nodal plane oriented parallel to the atomic absorption imaging axis

is obscured by the column integration inherent in the absorption imaging process. (b,e) A nodal structure factor is evident in the first-order Bragg peaks for this even-parity supermode-DW-polariton condensate, because the BEC sits at a cavity nodal plane oriented parallel to the atomic absorption imaging axis  . (c,f) By contrast, no nodal structure factor is evident for this nearly azimuthally symmetric supermode because (1) most atoms are located in the central antinode and (2) the nodal plane parallel to

. (c,f) By contrast, no nodal structure factor is evident for this nearly azimuthally symmetric supermode because (1) most atoms are located in the central antinode and (2) the nodal plane parallel to  is obscured by the atomic density in the ring parallel to

is obscured by the atomic density in the ring parallel to  . The high-order fringes along

. The high-order fringes along  in b are, we believe, the admixture into the supermode-DW-polariton condensate of a very high-order transverse mode or set of modes from a family of modes originating from half a free-spectral range lower in frequency. Although such modes are not common, we do find them at very specific detunings Δc from the cavity modes. The colourbar for cavity emission in a–c is to the right of a. The colourbar for d–f is to the right of d. For all panels, the axes are indicated with labelled arrows in a, for the atomic density, and in d, for cavity emission. The white scale bars equal a, twice the TEM00 optical waist 2w0=70 μm at the BEC; and d, the recoil wavevector kr=2π/λ with λ=780 nm.

in b are, we believe, the admixture into the supermode-DW-polariton condensate of a very high-order transverse mode or set of modes from a family of modes originating from half a free-spectral range lower in frequency. Although such modes are not common, we do find them at very specific detunings Δc from the cavity modes. The colourbar for cavity emission in a–c is to the right of a. The colourbar for d–f is to the right of d. For all panels, the axes are indicated with labelled arrows in a, for the atomic density, and in d, for cavity emission. The white scale bars equal a, twice the TEM00 optical waist 2w0=70 μm at the BEC; and d, the recoil wavevector kr=2π/λ with λ=780 nm.

Stronger pumping modifies the matter wavefunction by increasing the light–matter coupling nonlinearity, as may be seen by the emerging node at the centre of the zeroth-order and (±2, 0) Bragg peaks in Fig. 4k. This distortion of the condensate wavefunction is similar to that which happens in dilute gas BECs on increasing interaction energy. Lastly, we note that these supermode-DW-polariton condensates are observed to break the same Z2 symmetry observed in single-mode DW-polariton condensates21,22,30. Figure 6 presents measurements of pump-cavity field phase locking.

(a,c,e) Images of the photonic component of the supermode-DW-polariton condensates for which phase measurements are made. The supermode in a is TEM00, that in c is a mixture of α≈81% TEM02 and β≈19% TEM20, whereas the supermode in e is dominated by the TEM42 mode. (b,d,f) Heterodyne measurements of the phase of the supermode-DW-polariton condensates in a,c,e. The red overlay shows the power of the transverse pump versus time as the atoms self-organize and melt five times in the single experimental cycle. The supermode-DW-polariton condensate picks one of two possible phases, separated by ∼π, with respect to the transverse pump for each organization event. This is a signature of the Z2 symmetry being broken on condensation: the locking of phase corresponds to the two possible atomic checkerboard patterns21,22,30. (c–f) This phase locking is evident even for supermode-DW-polariton condensates with higher-order superpositions of the cavity supermodes. The colour field for cavity emission in a,c,e is to the right of a. For a,c,e, the axes are indicated with labelled arrows in e. The white scale bar in e equals twice the TEM00 optical waist 2w0=70 μm at the BEC.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate it is possible to study the DW polariton condensation phase transition when there are a few degenerate (or nearly degenerate) cavity modes. We have shown this has notable effects on properties such as the structure factor in the time-of-flight image of atomic density. The demonstration of this phase in the few-mode-degenerate system paves the way for measurements of critical behaviour in non-equilibrium quantum systems employing fully multimode cavity quantum electrodynamics. The multimode regime can be easily realized in our existing apparatus by tuning the cavity mirror spacing to confocality in situ. Indeed, this capability has already been achieved in our system in a robust manner, as discussed in ref. 31. To explore critical behaviour in phase transitions of open quantum systems, the crucial requirement is the existence of a continuum of modes, so that the response of the system at different length and timescales is not all dependent on the same few modes. The number of modes should be large enough that the beyond-mean-field corrections to the threshold power are greater than the ability to measure and control this threshold power.

Multimode cavity quantum electrodynamics, in the limit of multimode collective ultra-strong coupling wherein the collective coupling is larger than the bandwidth of the degenerate modes, strongly mixing them, should provide access to a much more exotic condensation transition. This fluctuation-induced first-order Brazovskii transition is predicted to yield a superfluid smectic-like quantum liquid crystalline order of the intracavity BEC23. This opens avenues to study the interplay of quantum liquid crystallinity and unconventional superfluidity under controlled dimensionality and disorder, as well as the study of superfluid glasses and spin glasses23,32, longstanding problems in statistical mechanics.

Methods

Apparatus

We prepare a nearly pure 87Rb BEC of 3 × 105 atoms at the centre of our cavity, confined in a crossed ODT with trap frequencies [ωx, ωy, ωz]=2π × [59.1(6), 88.0(9), 89.4(5)] Hz. The atoms are prepared in the  state and a 1.4 G magnetic field is oriented along the z axis. The Thomas–Fermi radii of the BEC [Rx, Ry, Rz]=[9.8(3), 8.3(2), 8.3(2)] μm are significantly smaller than the 35 μm waist (1/e radius of the cavity field) of the TEM00 cavity mode. The crossed ODT is formed by a pair of 1,064 nm laser beams with waists 39 and 20 μm intersecting at 45° in the xy plane. Acousto-optic modulators are used to stabilize the intensity of each ODT beam and control its position, allowing us to translate the BEC inside the cavity to control its overlap with the cavity modes.

state and a 1.4 G magnetic field is oriented along the z axis. The Thomas–Fermi radii of the BEC [Rx, Ry, Rz]=[9.8(3), 8.3(2), 8.3(2)] μm are significantly smaller than the 35 μm waist (1/e radius of the cavity field) of the TEM00 cavity mode. The crossed ODT is formed by a pair of 1,064 nm laser beams with waists 39 and 20 μm intersecting at 45° in the xy plane. Acousto-optic modulators are used to stabilize the intensity of each ODT beam and control its position, allowing us to translate the BEC inside the cavity to control its overlap with the cavity modes.

The cavity is operated in a near-confocal regime in which the length L is set to differ from the radius-of-curvature by 50 μm (ref. 31). The L=1 cm-long cavity has a free-spectral range of 15 GHz and a single-atom TEM00 cooperativity of 2.5: g0=2π × 1.04 MHz and κ=2π × 132 kHz. A weak 1,560 nm laser is used to stabilize the cavity length using the Pound–Drever–Hall method. In addition, light from this laser is amplified and doubled to generate 780 nm light for the transverse pump and longitudinal probe beams. The wavelength of the locking laser is chosen to achieve a large atomic detuning of Δa=−102 GHz between the pump and the 6 MHz-wide D2 line of 87Rb. An electro-optic modulator placed in the path of the locking laser beam allows us to tune the detuning Δc between the cavity modes and the pump or probe beams. The pump beam is polarized along x and is focused down to a waist of 80 μm at the BEC and retro-reflected to create an optical lattice oriented along y. At the cavity mirror, the TEM00 beam has a waist of 50 μm, which is much smaller than the mirror size. We have checked elsewhere31 that this remains true up to modes of order l, m≃50, and that these modes also exhibit high finesse. This provides an ultimate limit of around 1,250 on the number of transverse modes that can be made resonant exactly at the confocal point.

The cavity modes can be probed using a large, nearly flat longitudinal probe beam propagating along the axis of the cavity. This probe couples to all transverse modes of the low-order families. Reference 31 describes the design and vibration isolation of the length-adjustable cavity.

Measurements

The cavity output can be directed to three different detection channels. A single-photon counting module can record photon numbers via a multimode fibre coupled to the multimode cavity output. We measure a detection efficiency—from cavity output mirror to detector, including quantum efficiency and losses—of 10% for the low-order modes discussed here. The dispersive shift data in Fig. 2a is taken for an intracavity photon number much less than one and the same Δa as for the rest of the data, −102 GHz.

Superradiant emission from the cavity is observed by monitoring the cavity output on the single-photon counting module. A sharp rise in intracavity photon number as the pump power is increased heralds the condensation transition. See Figs 7 and 8.

(a) Cavity transmission, measured on a single photon counter, versus transverse pump power for three positions in the transverse plane of the cavity. Measurement at detuning Δc=−28.8 MHz from the TEM01 mode. The three positions are shown in b: 1 (dark blue) at the antinode of TEM10, 2 (red) in between modes and 3 (black) at the node at centre of the cavity. Onset of superradiance occurs at the same threshold for positions 1 and 2, whereas threshold for position 3 is much less sharp and at higher pump power, illustrating the poorer coupling when the BEC is at a node.

(a) A comparison between the thresholds for the l+m=0 (blue) and l+m=1 (red) modes for a BEC placed at the centre of the cavity. In both cases the BEC is pumped at a large detuning of Δc=−30 MHz. The l+m=0 mode has an antinode at the centre of the cavity, whereas the l+m=1 mode has a node. The overall higher threshold of the odd mode is indicative of the worse overlap between the atomic wavefunction and the node of the optical mode. The greater rate of threshold increase with pump power ramp rate indicates that the atoms need more time to adapt to the sign-flip of the odd mode than can be provided during the timescale of the faster ramp. Higher threshold pump power is needed to compensate. A consequence of this can be seen in the slow turn-on of superradiance in the data of Fig. 7b. This dynamical effect hints that motion of the atoms following the turn-on of the cavity light may in some cases lead to effects beyond the linear stability analysis presented in the Methods section, which produced the green curve in Fig. 2m. (b) An analogous behaviour is seen in the l+m=2 family, for the TEM02 (blue) and TEM11 (red) modes. The former has an antinode at the cavity centre, whereas the latter, although still an even-parity mode, has a node at the cavity centre. The thresholds were measured by pumping at a detuning Δc=−2 MHz from the respective cavity mode. Lines are guides to the eye. Error bars represent 1 s.e.

Alternatively, we can image the emission using an electron-multiplying CCD (charge-coupled device) camera, to spatially resolve the transverse mode content of the cavity emission, although with no temporal resolution. All images of cavity emission are taken in a single experimental run (no averaging of shots with different BEC realizations) and with a camera integration time between 1 and 3.3 ms. The lower signal-to-noise in the images of Fig. 2c–g versus Fig. 2h–l is due to lower intracavity photon number. The images in Fig. 2b with no atoms present are taken with intracavity photon number well above unity. The pump power in Fig. 4k is 70% larger than in Fig. 4j. See Fig. 9 for images of higher-order modes.

(a–e) Photonic components of various high-order supermode-DW-polariton condensates. Emission clipped at large radius by limited aperture of camera imaging optics at this magnification. The colourbar for cavity emission in a–e is to the right of b,e. For all a–e, the axes and scale are indicated with the labeled arrows and the white bar as in a, where the bar equals twice TEM00 the optical waist 2w0=70 μm at the BEC.

The phase difference between the cavity output and pump beam can be determined by performing a heterodyne measurement with a local oscillator beam22. The data in Fig. 6 has a frequency offset between pump and signal beams of 11 MHz.

We calibrate the Rabi frequency of the transverse pump by measuring the depth of the pump lattice through Kapitza–Dirac diffraction of the BEC. With the cavity modes detuned far-off resonance, we pulse the pump lattice onto the BEC for a time Δt. The BEC is then released from the trap and the population Pm(Δt) of the diffracted orders at momenta  is measured after a time-of-flight expansion. By fitting the measured Pm(Δt) to theory33, we extract a lattice depth V0=Ω2/Δa, which allows us to determine the Rabi frequency Ω of the pump.

is measured after a time-of-flight expansion. By fitting the measured Pm(Δt) to theory33, we extract a lattice depth V0=Ω2/Δa, which allows us to determine the Rabi frequency Ω of the pump.

The momentum distribution of the 87Rb cloud is measured by releasing the cloud from the trap and performing resonant absorption imaging after an expansion time tTOF=17 ms. The appearance of Bragg peaks at |k|= kr in the atomic momentum distribution coincides with the onset of superradiant emission. All atomic time-of-flight images are taken in a single experimental run (no averaging of shots with different BEC realizations). The paired atomic absorption and cavity output images in Fig. 4i,j and in Fig. 5a–f are each taken for the same experimental run. The cavity output image in Fig. 4l was taken for the same experimental run as the atomic absorption image in Fig. 4k.

kr in the atomic momentum distribution coincides with the onset of superradiant emission. All atomic time-of-flight images are taken in a single experimental run (no averaging of shots with different BEC realizations). The paired atomic absorption and cavity output images in Fig. 4i,j and in Fig. 5a–f are each taken for the same experimental run. The cavity output image in Fig. 4l was taken for the same experimental run as the atomic absorption image in Fig. 4k.

We use the position dependence of the l+m=1 supermode-DW-polariton condensates (see Fig. 3) to place our BEC at the centre of the cavity modes. The BEC is translated in the xy plane using the acousto-optic modulators of the two ODT beams. By monitoring the orientation of the superradiant emission as a function of BEC position, we are able to infer the displacement between the BEC and cavity centre. Exploiting these effects allows us to position the BEC at the cavity centre in both x and y directions to within 4 μm.

Mode decomposition

We analyse the transverse mode content of the polaritons in the l+m=s family by decomposing the cavity field into a superposition of unit-normalized, Hermite–Gaussian modes Φlm(x, y; w0, x0, y0). This is achieved by fitting the EMCCD image I(x, y) to the function

with the mode magnitudes Alm and phases φlm determined as fit parameters. The waist w0 and centre positions (x0, y0) of Hermite–Gaussians are determined from an image of the TEM00 cavity mode and are held fixed during the fit. Fixing the phase of the Φs0 modes to φs0=0 allows the fitting algorithm to converge to a local optimum. Using the fitted values of Alm, we extract admixture fractions

of the Φlm mode in the cavity output.

Model Hamiltonian

We model the coupled dynamics of the atomic wavefunction  and cavity modes

and cavity modes  (where μ=(l, m)) with the Hamiltonian

(where μ=(l, m)) with the Hamiltonian

The first term represents the evolution of the cavity modes and second is the familiar Gross–Pitaevskii Hamiltonian for a weakly interacting BEC trapped in a harmonic potential V(r). The atomic contact interaction is accounted for in the term proportional to U. In the regime of large atomic detuning Δa, we can neglect the excited electronic state of the atom, and the atom-light interactions may be described solely through the dispersive light shifts. The cavity–atom interaction becomes

where gν(r)=g0Φν(r)/Φ00(0) is the spatially dependent, single-photon (vacuum) Rabi frequency for the cavity mode ν. Similarly, for a pump field with a Rabi frequency Ω(r), the atom–pump interaction is

The last term of equation (3) represents the light shift arising from the interference between the cavity and pump fields and is written as

Simulation of supermode composition at threshold

To predict the location of threshold, and the nature of the supermode at that point, one may make use of a linear stability analysis, assuming a small occupation of the cavity modes and atomic DW excitation34,35. For the cavity mode, this is straightforward. For the atoms, this corresponds to assuming a condensate wavefunction

where μn(θ) are 2π periodic eigenfunctions of the Mathieu equation, with eigenvalue an, that is,

where q=−EΩ/ωr and EΩ=Ω2/Δa. These Mathieu functions describe the effects of the pump beam in the x direction and do not assume a weak pump lattice. In the cavity direction, z, the lattice is assumed weak and so we only consider the first two modes, that is, 1 and  cos(kx). As the above expression encapsulates all effects of the longitudinal coordinate, we will suppress the label ⊥ on the transverse coordinates.

cos(kx). As the above expression encapsulates all effects of the longitudinal coordinate, we will suppress the label ⊥ on the transverse coordinates.

We must then solve coupled equations for the atomic transverse envelope functions  and cavity mode amplitudes αμ. To leading order in perturbation theory, the ground state envelope

and cavity mode amplitudes αμ. To leading order in perturbation theory, the ground state envelope  does not change and so corresponds to the solution of the Gross–Pitaevskii equation:

does not change and so corresponds to the solution of the Gross–Pitaevskii equation:

where μ is the chemical potential and N the number of atoms.

Mean-field equations of motion for the  and

and  are derived from the Hamiltonian in equation (3),

are derived from the Hamiltonian in equation (3),

where we have taken Ω(r)=Ω cos(kx). The spatial dependence of the pump enters through the overlap  , of the first two Mathieu functions due to the cross pump–cavity light field potential. The energy scale ω0(q)=ωr(1+a1(q)−a0(q)) corresponds to the effective recoil in pump and cavity directions, allowing for the possibility of a deep pump lattice. For a shallow lattice these functions become 1 and 2ωr, respectively.

, of the first two Mathieu functions due to the cross pump–cavity light field potential. The energy scale ω0(q)=ωr(1+a1(q)−a0(q)) corresponds to the effective recoil in pump and cavity directions, allowing for the possibility of a deep pump lattice. For a shallow lattice these functions become 1 and 2ωr, respectively.

From these linearized equations, we may then determine when supermode-DW-polariton condensation occurs, by identifying the point at which the linearized fluctuations become unstable. There is some subtlety to this point, discussed further below. Calculating the growth/decay rates of linearized fluctuations is straightforward, corresponding to an eigenvalue equation. As there are anomalous coupling terms (that is, as αμ depends on both  and

and  , and vice versa) one must use the Bogoliubov–de Gennes parametrization, that is, write

, and vice versa) one must use the Bogoliubov–de Gennes parametrization, that is, write  and similarly for

and similarly for  . It is convenient to resolve the function

. It is convenient to resolve the function  onto some set of basis states. We use the harmonic oscillator basis states, giving a particularly simple result in the limit U→0.

onto some set of basis states. We use the harmonic oscillator basis states, giving a particularly simple result in the limit U→0.

With the basis noted above, the eigenvalue problem is given by Det[A−λ1]=0 where the matrix A can be written in the block form in terms of  blocks:

blocks:

In this expression, the various block matrices are as follows: the matrix Δc is a diagonal matrix consisting of the detuning between the pump laser and each cavity mode. Δdw(q) is similarly a diagonal matrix describing the energy difference between a given atomic transverse mode function and the ground state mode function. This is a function of q as it also includes the energy ω0(q) associated with the different scattering states. The matrices W denote the effect of atom-atom interactions, corresponding to the overlap between two atomic modes and the atomic ground state density. That is, they describe scattering off the condensate causing transitions between modes. The matrices M denote the dielectric shift due to the atoms, corresponding to the overlap between two cavity modes and the atomic ground state density. (The matrices M and W differ in general because the cavity beam waist does not match the harmonic oscillator length of the atoms.) The matrix Q denotes atom-cavity scattering and involves the overlap of the atomic ground-state mode function with a given excited mode and a given cavity mode. The energy scale is  for cavity beam waist w.

for cavity beam waist w.

The condition for the matrix A having unstable eigenvalues can be directly related to the idea of non-equilibrium condensation of polaritons36. As discussed there, one may directly relate the real frequencies at which the real and imaginary parts of the inverse retarded Green’s function vanish to the polariton energies and the effective chemical potential. At the point of condensation, these frequencies meet; that is, there exists a real frequency at which the inverse Green’s function vanishes. This point is equivalent to the boundary between the Green’s function having unstable and stable poles. For the single-mode cavity, this connection to condensation has been discussed extensively24,34, including the identification of the low energy effective temperature emerging at the transition. The Green’s function which defines all these quantities is directly related to equation (11), although conventional definitions of Green’s functions introduce minus signs in alternate rows and columns.

On solving equation (11), one finds that although there is a threshold for instability when Δc<0 of nearby modes, there is always an unstable eigenvalue as soon as Δc>0 for any mode (that is, the pump is blue-detuned of any mode). However, the growth rate of this instability varies widely with parameters. At low pump powers, the timescale for growth is very long (that is, seconds)35. As pump strength increases, there is a sharp threshold where two eigenvalues of equation (11) cross, demarcating a transition to a state that rapidly orders (timescale of microseconds). The curves in Fig. 2 correspond to finding the eigenvector (i.e., mode composition) of this mode which becomes rapidly unstable.

Structure factor simulation

The calculated density and momentum distributions presented in Fig. 4 are evaluated by numerically integrating the mean-field equations of motion in three dimensions for the atomic wavefunction and cavity mode. Using the Hamiltonian in equation (3), we derive equations of motion for the atomic wavefunction and cavity field under a mean-field approximation where  and

and  . This gives us the coupled differential equations,

. This gives us the coupled differential equations,

Furthermore, we adiabatically eliminate the cavity field αμ under the assumption that it equilibrates on a timescale much faster than the atomic motion. To simulate the behaviour presented in Fig. 4, we restrict αμ to a single mode, either TEM00 or TEM10, and numerically integrate the equations of motion. The initial atomic wavefunction is set to the Thomas–Fermi distribution associated with our ODT parameters and the initial cavity field is set to αμ(0)=0. The strength of the pump field is increased linearly in time from 0 to Ω(r, t) to simulate the transverse pumping of our cavity. The in situ density distributions shown in Fig. 4c–e are  . The momentum distributions are obtained by a Fourier transform of the in situ atomic wavefunction.

. The momentum distributions are obtained by a Fourier transform of the in situ atomic wavefunction.

Condensation of supermode DW polaritons

The model described above is specific to the case of condensation of supermode DW polaritons occurring on top of an existing BEC of atoms, as was studied experimentally. The phase transition to macroscopic occupation of cavity modes can however happen for both Bose condensed and thermal atoms22. Indeed, for a single-mode cavity, the distinction of the phase transitions for BEC of atoms and superradiance was discussed by Piazza et al.37, leading to a phase diagram where either phase can occur independently of the other. However, the signatures we study, such as the appearance of structure in the Bragg peaks from the time-of-flight image, would no longer be visible in the absence of atomic coherence18,19, that is, only for a coherent atomic state is the momentum distribution direction related by Fourier transformation to the density profile in real space.

The relation of the DW-polariton condensation transition to the coherence of atoms is complicated by the interpretation of single-mode DW-polariton condensation12 in terms of the Dicke model. This interpretation is based on the similarity to the proposed realisation of the Dicke model38 using two-photon transitions between hyperfine states of the atoms, later realized by Baden et al.15 In a single-mode cavity, DW-polariton states can be approximately mapped to this model12,13,34 as long as the atoms are Bose-condensed—in this case, two macroscopically occupied momentum states of the atoms play the rôle of the internal states in the proposal38. For a non-condensed cloud37, or for multimode cavities, such an approximation does not hold. Indeed, before the experiments on a condensate in a single-mode cavity, supermode-DW-polariton condensation in a multimode cavity had been discussed by Gopalakrishnan et al.23,39

Data availability

Parts of the research data supporting this publication can be accessed from ( http://dx.doi.org/10.17630/eddbeb14-9bab-4058-8033-cc4672770e0c). The remaining data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Kollár, A. J. et al. Supermode-density-wave-polariton condensation with a Bose–Einstein condensate in a multimode cavity. Nat. Commun. 8, 14386 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14386 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Bloch, I., Dalibard, J. & Zwerger, W. Many-body physics with ultracold gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 885–964 (2008).

Diehl, S., Tomadin, A., Micheli, A., Fazio, R. & Zoller, P. Dynamical phase transitions and instabilities in open atomic many-body systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 015702 (2010).

Sieberer, L. M., Huber, S. D., Altman, E. & Diehl, S. Dynamical critical phenomena in driven-dissipative systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 195301 (2013).

Deng, H., Weihs, G., Santori, C., Bloch, J. & Ya-mamoto, Y. Condensation of semiconductor microcavity exciton polaritons. Science 298, 199–202 (2002).

Kasprzak, J. et al. Bose-Einstein condensation of exciton polaritons. Nature 443, 409–414 (2006).

Balili, R., Hartwell, V., Snoke, D., Pfeiffer, L. & West, K. Bose-einstein condensation of microcavity polaritons in a trap. Science 316, 1007–1010 (2007).

Amo, A. et al. Collective fluid dynamics of a polariton condensate in a semiconductor microcavity. Nature 457, 291–295 (2009).

Manni, F., Lagoudakis, K. G., Liew, T. C. H., André, R. & Deveaud-Piédran, B. Spontaneous pattern formation in a polariton condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 106401 (2011).

Tosi, G. et al. Sculpting oscillators with light within a nonlinear quantum fluid. Nat. Phys. 8, 190–194 (2012).

Carusotto, I. & Ciuti, C. Quantum fluids of light. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 299–366 (2013).

Gao, T. et al. Observation of non-Hermitian degeneracies in a chaotic exciton-polariton billiard. Nature 526, 554–558 (2015).

Baumann, K., Guerlin, C., Brennecke, F. & Esslinger, T. Dicke quantum phase transition with a su-perfluid gas in an optical cavity. Nature 464, 1301–1306 (2010).

Nagy, D., Konya, G., Szirmai, G. & Domokos, P. Dicke-model phase transition in the quantum motion of a Bose-Einstein condensate in an optical cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 130401 (2010).

Ritsch, H., Domokos, P., Brennecke, F. & Esslinger, T. Cold atoms in cavity-generated dynamical optical potentials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 553–601 (2013).

Baden, M. P., Arnold, K. J., Grimsmo, A. L., Parkins, S. & Barrett, M. D. Realization of the Dicke model using cavity-assisted Raman transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 020408 (2014).

Wickenbrock, A., Hemmerling, M., Robb, G. R. M., Emary, C. & Renzoni, F. Collective strong coupling in multimode cavity QED. Phys. Rev. A 87, 043817 (2013).

Labeyrie, G. et al. ‘Optomechanical self-structuring in a cold atomic gas. Nat. Photonics 8, 321–325 (2014).

Klinder, J., Keßler, H., Bakhtiari, M. R., Thorwart, M. & Hemmerich, A. Observation of a superradiant Mott715 insulator in the Dicke-Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 230403 (2015).

Landig, R. et al. Quantum phases from competing short-and long-range interactions in an optical lattice. Nature 532, 476–479 (2016).

Kapon, E., Katz, J. & Yariv, A. Supermode analysis of phase-locked arrays of semiconductor lasers. Opt. Lett. 10, 125–127 (1984).

Domokos, P. & Ritsch, H. Collective cooling and self-organization of atoms in a cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 253003 (2002).

Black, A. T., Chan, H. W. & Vuletić, V. Observation of collective friction forces due to spatial self-organization of atoms: from Rayleigh to Bragg scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 203001 (2003).

Gopalakrishnan, S., Lev, B. L. & Gold-bart, P. M. Emergent crystallinity and frustration with Bose-Einstein condensates in multimode cavities. Nat. Phys. 5, 845–850 (2009).

Dalla Torre, E. G., Diehl, S., Lukin, M. D., Sachdev, S. & Strack, P. Keldysh approach for nonequilibrium phase transitions in quantum optics: beyond the Dicke model in optical cavities. Phys. Rev. A 87, 023831 (2013).

Marino, J. & Diehl, S. Driven Markovian quantum criticality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 070407 (2016).

Gopalakrishnan, S., Lev, B. L. & Goldbart, P. M. Frustration and glassiness in spin models with cavity-mediated interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 277201 (2011).

Chang, D. E., Cirac, J. I. & Kimble, H. J. Self-organization of atoms along a nanophotonic waveguide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 113606 (2013).

Strack, P. & Sachdev, S. Dicke quantum spin glass of atoms and photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 277202 (2011).

Siegman, A. E. Lasers Univ. Science Books (1986).

Asbóth, J. K., Domokos, P., Ritsch, H. & Vukics, A. Self-organization of atoms in a cavity field: Threshold, bistability, and scaling laws. Phys. Rev. A 72, 053417 (2005).

Kollár, A. J., Papageorge, A. T., Baumann, K., Ar-men, M. A. & Lev, B. L. An adjustable-length cavity and Bose-Einstein condensate apparatus for multimode cavity QED. New J. Phys. 17, 043012 (2015).

Habibian, H., Winter, A., Paganelli, S., Rieger, H. & Morigi, G. Bose-glass phases of ultracold atoms due to cavity backaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 075304 (2013).

Denschlag, J. H. et al. A Bose-Einstein condensate in an optical lattice. J. Phys. B 35, 3095–3110 (2002).

Keeling, J., Bhaseen, M. J. & Simons, B. D. Collective dynamics of Bose-Einstein condensates in optical cavities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 043001 (2010).

Bhaseen, M. J., Mayoh, J., Simons, B. D. & Keeling, J. Dynamics of nonequilibrium Dicke models. Phys. Rev. A 85, 013817 (2012).

Szymanska, M. H., Keeling, J. & Little-wood, P. B. in Quantum Gases: Finite Temperature and Non-Equilibrium Dynamics 1st edn eds Proukakis N. P., Gardiner S., Davis M. J., Szymanska M. H. Vol. 1, Ch. 30, Imperial College Press (2013).

Piazza, F., Strack, P. & Zwerger, W. Bose-Einstein condensation versus Dicke-Hepp-Lieb transition in an optical cavity. Ann. Phys. 339, 135–159 (2013).

Dimer, F., Estienne, B., Parkins, A. S. & Carmichael, H. J. Proposed realization of the Dicke-model quantum phase transition in an optical cavity QED system. Phys. Rev. A 75, 013804 (2007).

Gopalakrishnan, S., Lev, B. L. & Goldbart, P. M. Atom-light crystallization of Bose-Einstein condensates in multimode cavities: nonequilibrium classical and quantum phase transitions, emergent lattices, supersolidity, and frustration. Phys. Rev. A 82, 043612 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Gopalakrishnan for stimulating discussions, and J. Witmer, B. Pichler and N. Sarpa for early experimental assistance. Funding was provided by the Army Research Office. B.L.L. acknowledges support from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation, and A.J.K. and A.T.P. acknowledge support the NDSEG fellowship program. J.K. acknowledges support from EPSRC programme ‘TOPNES’ (EP/I031014/1) and from the Leverhulme Trust (IAF-2014-025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.L. and J.K. conceived of project. B.L., A.K. and A.P. designed and built experiment. A.K., V.V. and Y.G. took data. J.K. and A.P. performed simulations. B.L., J.K., V.V. and A.K. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kollár, A., Papageorge, A., Vaidya, V. et al. Supermode-density-wave-polariton condensation with a Bose–Einstein condensate in a multimode cavity. Nat Commun 8, 14386 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14386

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14386

This article is cited by

-

Synthesis and optical properties of II–VI semiconductor quantum dots: a review

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2023)

-

An optical lattice with sound

Nature (2021)

-

Strongly correlated Fermions strongly coupled to light

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Cavityless self-organization of ultracold atoms due to the feedback-induced phase transition

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Spontaneous light-mediated magnetism in cold atoms

Communications Physics (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.