Abstract

Cooling a mechanical resonator mode to a sub-thermal state has been a long-standing challenge in physics. This pursuit has recently found traction in the field of optomechanics in which a mechanical mode is coupled to an optical cavity. An alternate method is to couple the resonator to a well-controlled two-level system. Here we propose a protocol to dissipatively cool a room temperature mechanical resonator using a nitrogen-vacancy centre ensemble. The spin ensemble is coupled to the resonator through its orbitally-averaged excited state, which has a spin–strain interaction that has not been previously studied. We experimentally demonstrate that the spin–strain coupling in the excited state is 13.5±0.5 times stronger than the ground state spin–strain coupling. We then theoretically show that this interaction, combined with a high-density spin ensemble, enables the cooling of a mechanical resonator from room temperature to a fraction of its thermal phonon occupancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cooling a mechanical resonator to a sub-thermal phonon occupation can enhance sensing by lowering the resonator’s thermal noise floor and extending a sensor’s linear dynamic range1,2,3,4. Taken to the extreme, cooling a mechanical mode to the ground state of its motion enables the exploration of quantum effects at the mesoscopic scale5,6,7. These goals have motivated researchers in the field of optomechanics to invent methods for cooling mechanical resonators through their interactions with light. Such techniques have been able to achieve cooling to the ground state from cryogenic starting temperatures6,7 and to near the ground state from room temperature8,9,10,11,12.

A well-controlled quantum system coupled to the motion of a resonator can also be used to cool a mechanical mode13,14. Recently, nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centres in diamond have been coupled to mechanical resonators through coherent interactions with lattice strain15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. The opportunity to use these interactions has stimulated the development of single-crystal diamond mechanical resonators23,24,25,26 and motivated several theoretical proposals for cooling such resonators with a single NV centre13,14,27,28. In principle, replacing the single NV centre with a many-NV ensemble can provide a collective enhancement to the strain coupling, which could increase the cooling power of these protocols. In practice, however, ensembles can shorten spin coherence times and introduce inhomogeneities that may make collective enhancement impractical, depending on the proposed mechanism. To make ensemble coupling a useful resource, it thus becomes crucial to design a cooling protocol that is insensitive to these side effects.

In this work, we study the hybrid quantum system composed of an NV centre spin ensemble collectively coupled to a mechanical resonator with the goal of developing a method for cooling the resonator from ambient temperature. Experimentally, we characterize the previously unstudied spin–strain coupling within the room temperature NV centre excited state (ES), and we find that it is 13.5±0.5 times stronger than the ground state (GS) spin–strain interaction. We then propose a dissipative cooling protocol that uses this ES spin–strain interaction and theoretically show that a dense NV centre ensemble can cool a high-Q mechanical resonator from room temperature to a fraction of its thermal phonon population. The proposed protocol requires neither long spin coherence times nor strong spin-phonon coupling, and the cooling power scales directly with the NV centre density. These properties make our proposed protocol a practical approach to cooling a room temperature resonator.

Results

NV centre–strain interactions

To achieve substantial cooling from ambient conditions, we require a room temperature NV centre–strain interaction that can be enhanced by an ensemble. We first consider the orbital-strain coupling that exists within the NV centre ES at cryogenic temperatures. This 850±130 THz per strain interaction offers a promising route towards single NV centre-mechanical resonator hybrid quantum systems21,22. For ensemble coupling, however, inevitable static strain inhomogeneities will strongly broaden the orbital transition and prohibit collective enhancement. Moreover, the orbital coherence begins to dephase above 10 K because of phonon interactions29, limiting applications of orbital-strain coupling to cryogenic operation.

A weaker (21.5±1.2 GHz per strain) spin–strain coupling exists at room temperature within the NV centre GS (ref. 17). The resonance condition for this interaction is determined by a static magnetic bias field which can be very uniform across an ensemble. This GS spin–strain interaction thus offers a path towards coupling an ensemble to a mechanical resonator. As the NV centre density grows, however, the GS spin coherence will decrease30,31, limiting the utility of the collective enhancement.

Finally, we consider spin–strain interactions in the room temperature ES, which have not been thoroughly investigated but might provide the desired compatibility with dense ensembles. For temperatures above ∼150 K, orbital-averaging from the dynamic Jahn–Teller effect erases the orbital degree of freedom from the NV centre ES Hamiltonian, resulting in an effective orbital singlet ES at room temperature29,32,33,34. Previously, magnetic spectroscopy measured an unidentified spin splitting within the room temperature ES that is on the order of 10 times stronger than the GS spin–strain interaction. These measurements hinted that this splitting might be a spin–strain interaction in the ES (refs 35, 36). Like the GS spin–strain coupling, the resonance condition for such an interaction would be determined by a static magnetic bias field, enabling collective enhancement with an ensemble. Furthermore, the NV centre density is not expected to affect the ES coherence time, which is limited by the ES motional narrowing rate34,37. Such an ES spin–strain interaction could thus offer a promising path towards coupling a dense NV centre ensemble to a mechanical resonator. Our first goal then becomes to understand and precisely quantify this coupling.

Assuming this ES coupling is the result of a spin–strain interaction, we can write the spin Hamiltonian for an NV centre in the presence of a magnetic field B and non-axial strain  . Both the GS and room temperature ES Hamiltonians then take the form (ħ=1)36,38

. Both the GS and room temperature ES Hamiltonians then take the form (ħ=1)36,38

where  /2π=1.42 GHz and

/2π=1.42 GHz and  /2π=2.87 GHz are the ES and GS zero-field splittings, γNV/2π=2.8 MHz/G is the NV centre gyromagnetic ratio,

/2π=2.87 GHz are the ES and GS zero-field splittings, γNV/2π=2.8 MHz/G is the NV centre gyromagnetic ratio,  MHz (ref. 39) and

MHz (ref. 39) and  MHz are the ES and GS hyperfine couplings to the 14N nuclear spin, S (I) is the electronic (nuclear) spin-1 Pauli vector, and the z-axis runs along the NV centre symmetry axis. Perpendicular strain

MHz are the ES and GS hyperfine couplings to the 14N nuclear spin, S (I) is the electronic (nuclear) spin-1 Pauli vector, and the z-axis runs along the NV centre symmetry axis. Perpendicular strain  couples the

couples the  and

and  spin states with a strength

spin states with a strength  in the ES and

in the ES and  /2π=21.5±1.2 GHz per strain in the GS (ref. 17). As shown in Fig. 1a, this interaction enables direct control of the magnetically-forbidden

/2π=21.5±1.2 GHz per strain in the GS (ref. 17). As shown in Fig. 1a, this interaction enables direct control of the magnetically-forbidden  ←

← spin transition within each orbital through resonant strain.

spin transition within each orbital through resonant strain.

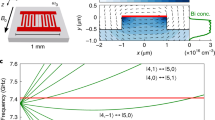

(a) NV center ground state and excited state energy levels as a function of the magnetic bias field. Energies have been plotted relative to the ms=0 state in each orbital, and a mechanical mode of frequency ωm has been drawn connecting the mI=+1 hyperfine sublevels. (b) Schematic of the device used in these measurements along with optical micrographs of the ZnO transducer used to generate the strain standing wave (150 μm scale bar) and the microwave antenna used to generate magnetic control fields (200 μm scale bar).

Device details

The combination of a large hyperfine splitting in the ES and a short ES lifetime broadens the spectral features of the ES spin–strain interaction. Measuring such a spectrum then requires large magnetic field sweeps  , which in turn require a mechanical driving field with a high carrier frequency

, which in turn require a mechanical driving field with a high carrier frequency  . To this end, we fabricate a high-overtone bulk acoustic resonator (HBAR) capable of generating large amplitude strain at gigahertz-scale frequencies. The resonator used in this work was driven at a ωm/2π=529 MHz mechanical mode that has a quality factor of Q=1,790±20. An antenna fabricated on the opposite diamond face provides high-frequency magnetic fields for magnetic spin control. The final device is pictured in Fig. 1b.

. To this end, we fabricate a high-overtone bulk acoustic resonator (HBAR) capable of generating large amplitude strain at gigahertz-scale frequencies. The resonator used in this work was driven at a ωm/2π=529 MHz mechanical mode that has a quality factor of Q=1,790±20. An antenna fabricated on the opposite diamond face provides high-frequency magnetic fields for magnetic spin control. The final device is pictured in Fig. 1b.

Spin–strain spectroscopy

To measure mechanical spin driving within the ES, we execute the pulse sequences shown in Fig. 2a, as a function of the magnetic bias field Bz. In the first sequence, a 532 nm laser initializes the NV centre ensemble into the GS level  . A magnetic adiabatic passage (AP) then moves the spin population to

. A magnetic adiabatic passage (AP) then moves the spin population to  . At this point, we pulse the mechanical resonator at its resonance frequency ωm for 3 μs. Just before the end of the mechanical pulse, we apply a

. At this point, we pulse the mechanical resonator at its resonance frequency ωm for 3 μs. Just before the end of the mechanical pulse, we apply a  =125 ns optical pulse with the 532 nm laser. This excites the ensemble to

=125 ns optical pulse with the 532 nm laser. This excites the ensemble to  and allows the spins to interact with the mechanical driving field in the ES. If the driving field is resonant with the

and allows the spins to interact with the mechanical driving field in the ES. If the driving field is resonant with the  ←

← splitting, population will be driven into

splitting, population will be driven into  . The spins then follow either a spin-conserving relaxation down to

. The spins then follow either a spin-conserving relaxation down to  or a relaxation to the singlet state

or a relaxation to the singlet state  through an intersystem crossing. The former preserves the spin state information, while relaxing to

through an intersystem crossing. The former preserves the spin state information, while relaxing to  re-initializes the state, erases the stored signal and reduces the overall contrast of the measurement. After allowing the ensemble to relax, we apply the second magnetic AP to return the spin population in

re-initializes the state, erases the stored signal and reduces the overall contrast of the measurement. After allowing the ensemble to relax, we apply the second magnetic AP to return the spin population in  to

to  and measure the

and measure the  population via fluorescence read out. We define this signal as S1 and plot it as a function of

population via fluorescence read out. We define this signal as S1 and plot it as a function of  in Fig. 2b.

in Fig. 2b.

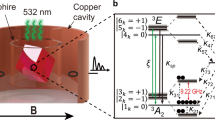

(a) Pulse sequences used to measure excited state (ES) spin driving. (b) Population in  at the end of the pulse sequences in a plotted against

at the end of the pulse sequences in a plotted against  . (c) Spectrum of the spin population driven mechanically into

. (c) Spectrum of the spin population driven mechanically into by the ES and ground state (GS) spin–strain interactions. The red curve is a least squares fit to the sum of six Lorentzians. (d) Zoomed in view of the GS spin transitions in c. The data in c,d were measured on one device with an NV centre ensemble, and error bars are from the s.d. in photon counting.

by the ES and ground state (GS) spin–strain interactions. The red curve is a least squares fit to the sum of six Lorentzians. (d) Zoomed in view of the GS spin transitions in c. The data in c,d were measured on one device with an NV centre ensemble, and error bars are from the s.d. in photon counting.

In the second pulse sequence, the mechanical pulse occurs between the second AP and fluorescence read out. Applying the mechanical pulse with the ensemble in  maintains the same power load on the device but does not drive spin population. This sequence measures S2, the re-initialization of the ensemble from the

maintains the same power load on the device but does not drive spin population. This sequence measures S2, the re-initialization of the ensemble from the  optical pulse (Fig. 2b). Subtracting S2−S1 gives the probability of finding the ensemble in

optical pulse (Fig. 2b). Subtracting S2−S1 gives the probability of finding the ensemble in  at the end of the first sequence. A third sequence with a single AP and a fourth with two APs (both with

at the end of the first sequence. A third sequence with a single AP and a fourth with two APs (both with  =0) normalize the spin contrast at each Bz.

=0) normalize the spin contrast at each Bz.

Figure 2c shows the resulting experimental signal. The three broad, low peaks correspond to the hyperfine-split  →

→ transition, providing definitive evidence of a spin–strain interaction within the room temperature ES. Population is also driven into

transition, providing definitive evidence of a spin–strain interaction within the room temperature ES. Population is also driven into  by the GS spin–strain interaction when the mechanical driving field is resonant with the

by the GS spin–strain interaction when the mechanical driving field is resonant with the  ←

← splitting. Figure 2c thus contains both ES and GS spectra. We fit the data to the sum of three low, broad Lorentzians describing the ES spin–strain interaction and three taller, narrower Lorentzians describing the GS interaction (see Methods). Figure 2d highlights the GS driving with a zoomed in view of Fig. 2c about the GS resonances. The GS peaks have larger amplitudes than the ES peaks because the GS interaction acts for the entire duration of the 3 μs mechanical pulse, whereas the ES interaction only acts during the ∼125 ns that the spin population is in the ES. Also, the reversed sign of

splitting. Figure 2c thus contains both ES and GS spectra. We fit the data to the sum of three low, broad Lorentzians describing the ES spin–strain interaction and three taller, narrower Lorentzians describing the GS interaction (see Methods). Figure 2d highlights the GS driving with a zoomed in view of Fig. 2c about the GS resonances. The GS peaks have larger amplitudes than the ES peaks because the GS interaction acts for the entire duration of the 3 μs mechanical pulse, whereas the ES interaction only acts during the ∼125 ns that the spin population is in the ES. Also, the reversed sign of  relative to

relative to  is consistent with ab initio calculations40 and was confirmed by measurements presented in Supplementary Note 1 that were conditional on the nuclear spin state.

is consistent with ab initio calculations40 and was confirmed by measurements presented in Supplementary Note 1 that were conditional on the nuclear spin state.

Quantification of

To quantify the strength of the ES spin–phonon interaction, we first calibrate the strain amplitude generated by the HBAR by mechanically driving Rabi oscillations within the GS and extracting the GS mechanical Rabi field Ωg as a function of the applied power (Fig. 3a). Next, we spectrally isolate the  ←

← transition by fixing Bz=80 G. At this field, the applied strain is on resonance in the ES but off resonance in the GS (Fig. 2c). We then execute a modified version of the pulse sequence described above. Here, we use ∼20 ns magnetic π-pulses to address the

transition by fixing Bz=80 G. At this field, the applied strain is on resonance in the ES but off resonance in the GS (Fig. 2c). We then execute a modified version of the pulse sequence described above. Here, we use ∼20 ns magnetic π-pulses to address the  ←

← transition and measure both S1 and S2 as a function of

transition and measure both S1 and S2 as a function of  for each power level applied to the HBAR.

for each power level applied to the HBAR.

(a) Mechanically driven Rabi oscillations within the ground state (GS) that have been fit using the procedure described in Supplementary Note 2. (b) Population in  plotted as a function of

plotted as a function of  . The red curves are least squares fits to a seven-level master equation model of the measurement. The data in a,b were measured on a single device with an NV centre ensemble, and error bars are from the s.d. in photon counting. (c) The excited state mechanical driving field plotted against the GS mechanical driving field and fit with a linear scaling. Each point corresponds to a single measurement, and error bars are standard error from the fits.

. The red curves are least squares fits to a seven-level master equation model of the measurement. The data in a,b were measured on a single device with an NV centre ensemble, and error bars are from the s.d. in photon counting. (c) The excited state mechanical driving field plotted against the GS mechanical driving field and fit with a linear scaling. Each point corresponds to a single measurement, and error bars are standard error from the fits.

As Fig. 3b shows, taking S2−S1 reveals a competition between mechanical driving into  and re-initialization into

and re-initialization into  via optical pumping. For nonzero

via optical pumping. For nonzero  , the ES mechanical driving field Ωe drives spin population from

, the ES mechanical driving field Ωe drives spin population from  to

to  , increasing

, increasing  , but as

, but as  grows, optical pumping re-initializes the ensemble into

grows, optical pumping re-initializes the ensemble into  , vacating the ms={+1, −1} subspace and reducing

, vacating the ms={+1, −1} subspace and reducing  to zero. A seven-level master equation model recreates this competition and provides good fits to the data. From these fits, we extract the value of Ωe. The Methods section includes a detailed description of this model, which was designed to account for inhomogeneities within the NV centre ensemble and for the polarization of the nuclear spin sublevels, among other effects. Plotting Ωe against Ωg (Fig. 3c) shows that the transverse spin–strain coupling in the ES is 13.5±0.5 times stronger than the GS coupling, or

to zero. A seven-level master equation model recreates this competition and provides good fits to the data. From these fits, we extract the value of Ωe. The Methods section includes a detailed description of this model, which was designed to account for inhomogeneities within the NV centre ensemble and for the polarization of the nuclear spin sublevels, among other effects. Plotting Ωe against Ωg (Fig. 3c) shows that the transverse spin–strain coupling in the ES is 13.5±0.5 times stronger than the GS coupling, or  /2π=290±20 GHz per strain.

/2π=290±20 GHz per strain.

Resonator cooling protocol

With  quantified, we now present a dissipative protocol for cooling a mechanical resonator with an NV centre spin ensemble. In our proposed protocol, a 532 nm laser continuously pumps the phonon sidebands of the ensemble’s optical transition, and a gigahertz frequency magnetic field continuously drives the

quantified, we now present a dissipative protocol for cooling a mechanical resonator with an NV centre spin ensemble. In our proposed protocol, a 532 nm laser continuously pumps the phonon sidebands of the ensemble’s optical transition, and a gigahertz frequency magnetic field continuously drives the  ←

← spin transition. This generates a steady state population surplus in

spin transition. This generates a steady state population surplus in  as compared with

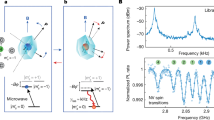

as compared with  , enabling the net absorption of phonons by the ensemble. Spontaneous relaxation and subsequent optical pumping continually re-initialize the system, allowing the phonon absorption cycle to continue. Figure 4a summarizes this process.

, enabling the net absorption of phonons by the ensemble. Spontaneous relaxation and subsequent optical pumping continually re-initialize the system, allowing the phonon absorption cycle to continue. Figure 4a summarizes this process.

(a) The seven NV centre orbital and spin states at room temperature. Fast (slow) transitions are indicated by solid (dashed) one-way arrows. Coherent couplings are indicated by two-way arrows. (b) The toy model depiction of the proposed cooling protocol. (c) Schematic of a doubly-clamped beam. (d) Final phonon number achieved by the cooling protocol as a function of the density of properly aligned NV centers. Vertical lines indicate densities that have been realized in single-crystal diamonds (7.0 × 1017 cm−3 (ref. 31), 1.1 × 1018 cm−3 (ref. 58), 2.0 × 1018 cm−3 (ref. 56)) and nanodiamonds (4 × 1020 cm−3 (ref. 57)).

The dissipative nature of this protocol enables resonator cooling without requiring strong spin-phonon coupling. Here, we define strong coupling as a single-spin cooperativity  , where λ is the single spin-single phonon coupling strength,

, where λ is the single spin-single phonon coupling strength,  is the inhomogeneous spin dephasing time, γ=ωm/Q is the mechanical dissipation rate and

is the inhomogeneous spin dephasing time, γ=ωm/Q is the mechanical dissipation rate and  is the thermal phonon occupancy of the resonator mode41. A cooperativity of η>1 marks the threshold for coherent interactions between the spin and the mechanical mode. Non-idealities in spin coherence and resonator fabrication have thus far prevented the experimental realization of NV centre cooperativities approaching unity, especially at room temperature. This makes the proposed dissipative protocol a practical and attractive approach because it does not require coherent interactions for resonator cooling to occur.

is the thermal phonon occupancy of the resonator mode41. A cooperativity of η>1 marks the threshold for coherent interactions between the spin and the mechanical mode. Non-idealities in spin coherence and resonator fabrication have thus far prevented the experimental realization of NV centre cooperativities approaching unity, especially at room temperature. This makes the proposed dissipative protocol a practical and attractive approach because it does not require coherent interactions for resonator cooling to occur.

To analyse the performance of the protocol we start by considering a single two-state spin system coupled to a mechanical resonator. The resulting dynamics obey the master equation (ħ=1)

where H describes the coherent coupling between the spin and the resonator,  describes the incoherent spin processes, and

describes the incoherent spin processes, and  describes the resonator rethermalization. For resonant coupling, the quantized Hamiltonian in the Jaynes–Cummings form is42

describes the resonator rethermalization. For resonant coupling, the quantized Hamiltonian in the Jaynes–Cummings form is42

where a† (a) is the creation (annihilation) operator for the mechanical mode and S± are the ladder operators for the spin state. The spin relaxation term in equation (2) takes the form  , where

, where  is the Lindblad superoperator and T1

is the Lindblad superoperator and T1  is the transverse (longitudinal) spin coherence time. The resonator rethermalization is described by

is the transverse (longitudinal) spin coherence time. The resonator rethermalization is described by  .

.

Within this two-state model, an analytic expression for the steady state phonon number nf can be found by using the matrix of second order moments (Supplementary Note 3)43. Under the secular approximation and working in the limit  , the dynamical equation for the phonon occupancy n=<a†a> can be simplified to

, the dynamical equation for the phonon occupancy n=<a†a> can be simplified to

For an ensemble of N spins coupled to the resonator but not to one another, each spin will add an additional damping term to the resonator dynamical equation. This allows us to rewrite the last term in equation (4) as  . If each spin within the ensemble has the same T1 and

. If each spin within the ensemble has the same T1 and  , we can factorize this expression and replace the individual λi with an effective ensemble-resonator coupling

, we can factorize this expression and replace the individual λi with an effective ensemble-resonator coupling  . For the case of uniform coupling, this simplifies to

. For the case of uniform coupling, this simplifies to  , which is equivalent to the effective coupling in the Tavis–Cummings model44,45. Solving for the steady state of the system then gives

, which is equivalent to the effective coupling in the Tavis–Cummings model44,45. Solving for the steady state of the system then gives

The problem now becomes mapping the seven-level NV centre structure pictured in Fig. 4a onto this two-state spin system. We do this by distilling the seven-level landscape to a toy model that contains only the two-states that couple to the mechanical resonator,  and

and  , as shown in Fig. 4b. Within this simplified landscape, we assign

, as shown in Fig. 4b. Within this simplified landscape, we assign  to be the ES coherence time (

to be the ES coherence time ( =6.0 ns (ref. 46)) and T1 to be the ES lifetime of

=6.0 ns (ref. 46)) and T1 to be the ES lifetime of  (T1e=6.89 ns (ref. 47)). At any one moment, only a fraction α of the spins within the ensemble will be in the proper

(T1e=6.89 ns (ref. 47)). At any one moment, only a fraction α of the spins within the ensemble will be in the proper  subspace to participate in the cooling. We account for this by modifying

subspace to participate in the cooling. We account for this by modifying  . To determine α, we solve for the 7 × 7 density matrix describing the steady state of the ensemble in the absence of the mechanical resonator, calculate the population difference between

. To determine α, we solve for the 7 × 7 density matrix describing the steady state of the ensemble in the absence of the mechanical resonator, calculate the population difference between  and

and  , and obtain α=0.017 for optimized control fields (Supplementary Note 4).

, and obtain α=0.017 for optimized control fields (Supplementary Note 4).

Elasticity theory provides a means of calculating the remaining device parameters. For a doubly-clamped beam of length l, thickness t and width w, we compute λeff from the strain because of the zero-point motion of the resonator  (y, z) with coordinates as defined in Fig. 4c (see Methods). For a uniform distribution of properly aligned NV centres at a density ν, we obtain41,48

(y, z) with coordinates as defined in Fig. 4c (see Methods). For a uniform distribution of properly aligned NV centres at a density ν, we obtain41,48

Evaluating equation (6), we find that λeff is independent of w and scales as  where

where  , κ0=120 GHz·μm, and E=1,200 GPa is the Young’s modulus of diamond. The frequency of the resonator’s fundamental mode scales as ωm=κ0t/l2. As described in Supplementary Note 5, higher order mechanical modes are spectrally isolated from the NV centre spin dynamics in the devices considered here17,41. For any thin-beam resonator in the resolved-sideband regime

, κ0=120 GHz·μm, and E=1,200 GPa is the Young’s modulus of diamond. The frequency of the resonator’s fundamental mode scales as ωm=κ0t/l2. As described in Supplementary Note 5, higher order mechanical modes are spectrally isolated from the NV centre spin dynamics in the devices considered here17,41. For any thin-beam resonator in the resolved-sideband regime  , the fractional cooling nf/nth is insensitive to the physical dimensions of the resonator because the size of the ensemble scales with the size of the resonator. This can be seen by rewriting equation (5) as nf/nth=(1+χ)−1, where

, the fractional cooling nf/nth is insensitive to the physical dimensions of the resonator because the size of the ensemble scales with the size of the resonator. This can be seen by rewriting equation (5) as nf/nth=(1+χ)−1, where  is independent of the resonator dimensions. For illustrative purposes, we choose to examine a resonator with a ωm/2π=1 GHz fundamental mode and assume fully polarized nuclear spins49. Potential device dimensions then become (l, t)=(1.9, 0.19) μm. Finally, phonon–phonon interactions limit the Q of an ideal diamond mechanical resonator at room temperature. For modes satisfying ωm/2π >1/

is independent of the resonator dimensions. For illustrative purposes, we choose to examine a resonator with a ωm/2π=1 GHz fundamental mode and assume fully polarized nuclear spins49. Potential device dimensions then become (l, t)=(1.9, 0.19) μm. Finally, phonon–phonon interactions limit the Q of an ideal diamond mechanical resonator at room temperature. For modes satisfying ωm/2π >1/ , the maximum Q=2 × 106 is independent of ωm (ref. 50), and we now have all the parameters needed to study the performance of the protocol.

, the maximum Q=2 × 106 is independent of ωm (ref. 50), and we now have all the parameters needed to study the performance of the protocol.

At this point, we note that distilling a seven-state model to the toy model we employ certainly requires validation. To justify our simplified model, we calculate the cooling predicted within the toy model and compare this both to an analytical Lamb–Dicke treatment of the seven-level model14,51 and to numerical simulations of a small number of seven-level NV centres coupled to a resonator. Because of the exponential growth of the Hilbert space, full seven-level numerical simulations were performed on the Titan supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, with the most intensive simulations taking ∼104 core-hours. Comparing the toy model and Lamb–Dicke results to the numerical simulations, we determined that the two-level distillation outperforms the Lamb–Dicke approach in all test cases and provides an upper bound on nf (Supplementary Note 6). This indicates that the proposed protocol cools a resonator more efficiently than our toy model predicts52,53,54,55.

Cooling performance

The lowest phonon occupancy that can be reached depends strongly on the density of properly aligned NV centres ν. For instance, Choi, et al. reported measurements of an NV centre ensemble with ν=2.0 × 1018 cm−3 in single-crystal diamond56. For this density and Q=2 × 106, we find that the proposed protocol cools a room temperature resonator to nf=0.86nth. Using the same Q and the density of ν=4 × 1020 cm−3 reported by Baranov, et al. in nanodiamonds57, however, the protocol can cool to nf=0.03nth.

Increasing the size of the ensemble can thus dramatically increase the protocol’s cooling power. The magnetic field noise from paramagnetic impurities will also grow with ν, degrading the GS coherence time. However, for large magnetic driving fields, this cooling protocol does not require a lengthy GS coherence time (Supplementary Note 4). The only coherence time that effects the protocol is  , which is not expected to change with the defect density34,37. This means that large NV centre densities could in principle be used to cool a resonator with the ES spin–strain interaction. To study how increasing ν affects the protocol, we plot nf against ν in Fig. 4d for several different Q-values. For reference, we have included lines marking values of ν that have been realized in single-crystal diamonds31,56,58 and in nanodiamonds57. The limiting density of NV centres in a single-crystal diamond nanostructure is currently unknown. Furthermore, while high defect densities have been shown to degrade the Q of

, which is not expected to change with the defect density34,37. This means that large NV centre densities could in principle be used to cool a resonator with the ES spin–strain interaction. To study how increasing ν affects the protocol, we plot nf against ν in Fig. 4d for several different Q-values. For reference, we have included lines marking values of ν that have been realized in single-crystal diamonds31,56,58 and in nanodiamonds57. The limiting density of NV centres in a single-crystal diamond nanostructure is currently unknown. Furthermore, while high defect densities have been shown to degrade the Q of  frequency resonators59, it remains to be seen how the gigahertz frequency resonators of interest here will be affected by the incorporation of a dense defect ensemble. These questions motivate future experimental work.

frequency resonators59, it remains to be seen how the gigahertz frequency resonators of interest here will be affected by the incorporation of a dense defect ensemble. These questions motivate future experimental work.

Discussion

The insensitivity of the proposed protocol to the GS coherence time makes an ES cooling protocol an attractive and practical route to cooling a room temperature mechanical resonator with NV centres. Alternative approaches that use the GS spin–strain coupling18,19,25 are incompatible with the collective enhancement from a dense ensemble that makes the proposed protocol viable. Although the GS inhomogeneous dephasing time  can be ∼μs long in high purity diamonds,

can be ∼μs long in high purity diamonds,  scales roughly as

scales roughly as  in bulk diamond and can be <100 ns for dense ensembles30,31. Within a nanostructure, effects such as exchange narrowing and the truncation of the spin bath mitigate this reduction in

in bulk diamond and can be <100 ns for dense ensembles30,31. Within a nanostructure, effects such as exchange narrowing and the truncation of the spin bath mitigate this reduction in  (refs 57, 60) and make it difficult to predict the decrease in

(refs 57, 60) and make it difficult to predict the decrease in  inside a doubly-clamped beam. Nevertheless, we can roughly compare the ES and GS spin–strain interactions by calculating η using coherence times measured in bulk diamond (Supplementary Note 7). For a moderate NV centre density of ν=2.8 × 1013 cm−3 (ref. 18), the single-spin cooperativity for the ES spin–strain interaction is 2.4-times larger than in the GS, and for ν=7.0 × 1017 cm−3 (ref. 31), η is 19-times larger in the ES. In both cases, the ES offers the more efficient route to cooling, and as the collective enhancement grows, the ES interaction becomes increasingly more efficient than the GS interaction. A dense ensemble coupled via the ES spin–strain interaction thus becomes the more promising route to cooling a room temperature mechanical resonator with NV centres.

inside a doubly-clamped beam. Nevertheless, we can roughly compare the ES and GS spin–strain interactions by calculating η using coherence times measured in bulk diamond (Supplementary Note 7). For a moderate NV centre density of ν=2.8 × 1013 cm−3 (ref. 18), the single-spin cooperativity for the ES spin–strain interaction is 2.4-times larger than in the GS, and for ν=7.0 × 1017 cm−3 (ref. 31), η is 19-times larger in the ES. In both cases, the ES offers the more efficient route to cooling, and as the collective enhancement grows, the ES interaction becomes increasingly more efficient than the GS interaction. A dense ensemble coupled via the ES spin–strain interaction thus becomes the more promising route to cooling a room temperature mechanical resonator with NV centres.

It is important to note that this analysis of the proposed protocol only applies for operation at room temperature. Reducing the bath temperature will lower nth and would thus ideally lower nf. However, the ES coherence time is limited by the ES motional narrowing rate, which increases as the bath temperature decreases34,37. This is expected to lead to a reduction in  at lower temperatures, followed by a complete loss of ES spin coherence below ∼150 K (ref. 32). As seen from equation (5), a reduction in

at lower temperatures, followed by a complete loss of ES spin coherence below ∼150 K (ref. 32). As seen from equation (5), a reduction in  will lead to a loss of cooling power. For cryogenic starting temperatures, it thus becomes necessary to use either the GS spin-phonon interaction or the orbital-strain interaction to cool a mechanical resonator with NV centres.

will lead to a loss of cooling power. For cryogenic starting temperatures, it thus becomes necessary to use either the GS spin-phonon interaction or the orbital-strain interaction to cool a mechanical resonator with NV centres.

Finally, nf could be lowered further by simultaneously implementing an optomechanical cooling protocol8,9,10,11,12 alongside the proposed protocol. Optomechanical cooling has been demonstrated to cool gigahertz frequency resonators to  (refs 6, 61). The cooling rate from an optimized realization of the proposed protocol would combine additively with the optomechanical cooling rate, allowing the two complementary techniques to operate in conjunction and enhance the total cooling.

(refs 6, 61). The cooling rate from an optimized realization of the proposed protocol would combine additively with the optomechanical cooling rate, allowing the two complementary techniques to operate in conjunction and enhance the total cooling.

In conclusion, we have proposed a dissipative protocol for cooling a room temperature mechanical resonator that utilizes an ensemble of NV centre spins to realize a collective enhancement in the spin-phonon coupling. After experimentally determining that the spin–strain coupling in the room temperature ES is 13.5±0.5 times stronger than the GS spin–strain coupling, we analysed the performance of the cooling protocol. For very dense NV centre ensembles, the proposed protocol can cool a room temperature resonator to a fraction of its thermal phonon occupancy. These results shed further light on the orbitally-averaged room temperature ES of the NV centre and demonstrate a practical path towards cooling a room temperature mechanical resonator with NV centres.

Methods

Sample details

Our HBAR consists of a 2.5 μm-thick ZnO piezoelectric film sandwiched between a 25/200 nm Ti/Pt ground plane and a 250 nm thick apodized Al top electrode, all sputtered on one face of a <100> single-crystal diamond substrate. Applying a high-frequency voltage to this transducer launches acoustic waves into the diamond, which then serves as a Fabry–Pérot cavity to generate a comb of standing wave resonances. By apodizing the shape of the Al electrode, we mitigate the loss of power into lateral modes formed across the diameter of the HBAR. The antenna fabricated on the opposite diamond face was patterned from 25/225 nm Ti/Pt with a lift-off process.

The CVD-grown diamond used in these measurements contained NV centres at a density of ∼4 × 1014 cm−3 as purchased. Our measurements thus address an ensemble of ∼70 NV centres oriented with their symmetry axis parallel to Bz. NV centres of different orientations are spectrally isolated and contribute only a constant background to the measurements.

Spectrum fitting

The spectrum pictured in Fig. 2 was fit to the function

where ce and cg are constant amplitudes that quantify the driven spin contrast for the ES and GS resonances, ai[Bz] are field-dependent scaling factors that account for the dynamic nuclear polarization of the hyperfine sublevels49, Γe (Γg) is the FWHM of the ES (GS) resonances, B0 is the resonant field for the mI=0 hyperfine sublevel, and the other parameters are as defined above. Of these variables, ci, Γi, and B0 are free parameters in our fitting procedure.

We calibrate ai[Bz] by performing hyperfine-resolved magnetically-driven electron spin resonance (ESR) measurements within the NV centre GS at different values of the magnetic bias field Bz. This is done by fixing Bz and monitoring the NV centre photoluminescence as the carrier frequency of a magnetic driving field oriented along Bx is swept through the  ←

← spin resonance. We fit the resulting curves to the function

spin resonance. We fit the resulting curves to the function

where P is the measured photoluminescence, C accounts for the driven spin contrast, Ai is the relative amplitude of each hyperfine sublevel, P0 is the background photoluminescence, and we fix ∑ Ai=1. Figure 5a,b shows ESR curves measured at Bz=20.2 G and 171 G. We have used the values of P0 returned from the fits to normalize the photoluminescence.

(a,b) Normalized photoluminescence (P.L.) plotted as a function of the magnetic driving field carrier frequency for (a) Bz=20.2 G and (b) Bz=171.5 G. The solid line in each plot is a least squares fit to the sum of three Lorentzians. The data in a,b was measured on a single device with an NV centre ensemble, and error bars are from the s.d. in photon counting. (c) Normalized amplitude of each mI hyperfine sublevel as a function of Bz. The solid lines are least squares fits to a linear model, each point corresponds to a single measurement, and error bars are standard error from the fits.

Figure 5c shows the normalized amplitude of each nuclear sublevel plotted as a function of Bz. As expected, the nuclear polarization increases in the direction of the ES level anti-crossing at  =507 G. In this figure, we have fit each curve to a straight line with a fixed y-intercept of

=507 G. In this figure, we have fit each curve to a straight line with a fixed y-intercept of  to obtain the linear scaling functions ai[Bz] in equation (7). The sum of these scaling functions satisfies ∑ ai[Bz]=1.

to obtain the linear scaling functions ai[Bz] in equation (7). The sum of these scaling functions satisfies ∑ ai[Bz]=1.

Seven-level master equation model

The master equation used to model our ES spin driving measurements is derived in the room temperature NV centre basis defined by the states  where, within the e and g subspaces, a subscript denotes the ms value. The 7 × 7 density matrix evolves according to (ħ=1)

where, within the e and g subspaces, a subscript denotes the ms value. The 7 × 7 density matrix evolves according to (ħ=1)

In the rotating frame, the Hamiltonian is given by

where Δm is the mechanical detuning. The incoherent NV centre processes are described by the superoperator

where we define

Here, Γopt is the optical pumping rate of our 532 nm laser,  =6.0±0.8 ns is the ES coherence time46, and the relaxation rates kij are listed in Table 1. Figure 6a summarizes this landscape47.

=6.0±0.8 ns is the ES coherence time46, and the relaxation rates kij are listed in Table 1. Figure 6a summarizes this landscape47.

(a) States and transitions included in our seven-level master equation model. The kij rates are listed in Table 1. (b) Excited state mechanical driving field Ωe plotted as a function of the ground state mechanical driving field Ωg with the data labelled by the optical pumping rate Γ0 during each measurement. Each point corresponds to a single measurement, and error bars are standard error from the fits.

Because optical initialization does not generate a pure state, we first simulate the optical pumping process to obtain an initialized density matrix. To do so, we start with a thermal state  and apply equation (9) with Ωe, Δm=0 and Γopt≠0 for 10 μs. We take the resulting density matrix and apply equation (9) for 5 μs with Ωe, Δm, Γopt=0 to simulate the relaxation to

and apply equation (9) with Ωe, Δm=0 and Γopt≠0 for 10 μs. We take the resulting density matrix and apply equation (9) for 5 μs with Ωe, Δm, Γopt=0 to simulate the relaxation to  . A simulated π-pulse then swaps ρ22 and ρ33, providing the appropriate starting density matrix ρ0 for a given Γopt. From ρ0, we also extract the minimum and maximum spin contrast (

. A simulated π-pulse then swaps ρ22 and ρ33, providing the appropriate starting density matrix ρ0 for a given Γopt. From ρ0, we also extract the minimum and maximum spin contrast ( and

and  ), which allow us to properly normalize our simulations.

), which allow us to properly normalize our simulations.

Next, we model the measurement of S2, the spin re-initialization. To do so, we apply equation (9) to ρ0 with Ωe, Δm=0 and Γopt≠0 for a length of time  . Allowing the spin to relax as before gives us the measured density matrix ρ2. We normalize

. Allowing the spin to relax as before gives us the measured density matrix ρ2. We normalize  using smin and smax, and repeat this simulation as a function of

using smin and smax, and repeat this simulation as a function of  to obtain a simulated S2 curve.

to obtain a simulated S2 curve.

To account for spatial inhomogeneities in the optical power within the NV centre ensemble, we perform a weighted average of this simulation over the point spread function (PSF) of our microscope. We approximate the PSF by the function

where Γ0 is the peak optical pumping rate, κ[z0] defines the depth-dependent PSF width15, z is the distance below the diamond surface, and z0=7.9±0.9 μm is the focus depth of the PSF. An ensemble measurement is then given by

We discretize this integral to make it computationally tractable and perform a least squares fit of  to the measured data. Γ0 is the only free parameter in the fitting procedure.

to the measured data. Γ0 is the only free parameter in the fitting procedure.

With the exception of the datum indicated in Fig. 6b, all of the measurements were taken at the same optical power. We simultaneously fit each of these S2 curves and find Γ0=19.1±1.6 MHz. For the measurement at a different optical power, we find Γ0=16.5±1.7 MHz.

To extract Ωe, we then fix Γ0 and repeat this procedure with Ωe≠0 to simulate the S2−S1 measurement pictured in Fig. 3b. To account for inhomogeneities in the mechanical driving field, we must also include the spatial profile of the strain standing wave inside the weighted average. This function takes the form  where λ=31±4 μm is the wavelength of the strain wave. Defining the results of such a simulation as

where λ=31±4 μm is the wavelength of the strain wave. Defining the results of such a simulation as  (Ωe, Δm), we account for the hyperfine sublevels by computing the sum

(Ωe, Δm), we account for the hyperfine sublevels by computing the sum

where the normalized amplitudes (∑ ai=1) account for nuclear spin polarization and have been measured separately via magnetic ESR. A least squares fit of equation (15) to the data then provides Ωe. Here, Ωe is the only free parameter in the fitting procedure.

When fitting the relation between Ωe and Ωg (Fig. 3c), we fix the y-intercept of the linear fitting function to be zero.

Elasticity theory

To analyse how strain couples to NV centres within a resonator, we start by assuming that the NV centres are aligned with the direction of beam deflection such that the strain in an oscillating beam is entirely perpendicular to the NV centre symmetry axis. We then use elasticity theory to derive the scaling laws quoted above17,41.

The wave equation for doubly-clamped beams is

where φ(t, z) is the transverse displacement in the y-direction,  points along the beam as indicated in Fig. 4c, A=wt is the cross-sectional area of the resonator, E=1,200 GPa is the Young’s modulus of diamond, ρd=3.515 g cm−3 is the mass density of diamond, and I=wt3/12 is the resonator’s moment of inertia. Solutions are of the form φ(z, t)=u(z)e−iωt where

points along the beam as indicated in Fig. 4c, A=wt is the cross-sectional area of the resonator, E=1,200 GPa is the Young’s modulus of diamond, ρd=3.515 g cm−3 is the mass density of diamond, and I=wt3/12 is the resonator’s moment of inertia. Solutions are of the form φ(z, t)=u(z)e−iωt where

and the allowed k-vectors satisfy cos(knz) cosh(knz)=1. The wave vector and amplitudes of the fundamental mode satisfy k0l=4.73 and a0/b0=1.0178.

We normalize un(z) by setting the free energy of the beam equal to the zero point energy of the mode:

where the eigenfrequencies of the resonator are given by  . This expression for ωn can be simplified to ωn=κnt/l2, where

. This expression for ωn can be simplified to ωn=κnt/l2, where  . For the fundamental mode, κ0=120 GHz·μm as quoted above.

. For the fundamental mode, κ0=120 GHz·μm as quoted above.

The spin-phonon coupling for a single NV centre located at (y, z) is given by λ=d⊥ (y, z) where

(y, z) where  is the strain from the zero point motion of the resonator mode. Here, the y-axis is zeroed at the neutral axis of the resonator. To compute the effective ensemble-resonator coupling, we assume a uniform distribution of properly aligned NV centres within the resonator and sum the individual couplings in quadrature according to

is the strain from the zero point motion of the resonator mode. Here, the y-axis is zeroed at the neutral axis of the resonator. To compute the effective ensemble-resonator coupling, we assume a uniform distribution of properly aligned NV centres within the resonator and sum the individual couplings in quadrature according to  , which gives equation (6).

, which gives equation (6).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: MacQuarrie, E. R. et al. Cooling a mechanical resonator with nitrogen-vacancy centres using a room temperature excited state spin–strain interaction. Nat. Commun. 8, 14358 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14358 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

29 November 2017

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Albrecht, T. R., Grütter, P., Horne, D. & Rugar, D. Frequency modulation detection using high-Q cantilevers for enhanced force microscope sensitivity. J. Appl. Phys. 69, 668–673 (1991).

Cleland, A. N. & Roukes, M. L. A nanometre-scale mechanical electrometer. Nature 392, 160–162 (1998).

Rugar, D., Budakian, R., Mamin, H. J. & Chui, B. W. Single spin detection by magnetic resonance force microscopy. Nature 430, 329–332 (2004).

Poggio, M., Degen, C. L., Mamin, H. J. & Rugar, D. Feedback cooling of a cantilever’s fundamental mode below 5 mk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 017201 (2007).

O’Connell, A. D. et al. Quantum ground state and single-phonon control of a mechanical resonator. Nature 464, 697–703 (2010).

Chan, J. et al. Laser cooling of a nanomechanical oscillator into its quantum ground state. Nature 478, 89–92 (2011).

Teufel, J. D. et al. Sideband cooling of micromechanical motion to the quantum ground state. Nature 475, 359–363 (2011).

Metzger, C. H. & Karrai, K. Cavity cooling of a microlever. Nature 432, 1002–1005 (2004).

Gigan, S. et al. Self-cooling of a micromirror by radiation pressure. Nature 444, 67–70 (2006).

Arcizet, O., Cohadon, P.-F., Briant, T., Pinard, M. & Heidmann, A. Radiation-pressure cooling and optomechanical instability of a micromirror. Nature 444, 71–74 (2006).

Kleckner, D. & Bouwmeester, D. Sub-Kelvin optical cooling of a micromechanical resonator. Nature 444, 75–78 (2006).

Schliesser, A., Del’Haye, P., Nooshi, N., Vahala, K. J. & Kippenberg, T. J. Radiation pressure cooling of a micromechanical oscillator using dynamical backaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 243905 (2006).

Rabl, P. et al. Strong magnetic coupling between an electronic spin qubit and a mechanical resonator. Phys. Rev. B 79, 041302 (2009).

Kepesidis, K. V., Bennett, S. D., Portolan, S., Lukin, M. D. & Rabl, P. Phonon cooling and lasing with nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 88, 064105 (2013).

MacQuarrie, E. R., Gosavi, T. A., Jungwirth, N. R., Bhave, S. A. & Fuchs, G. D. Mechanical spin control of nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 227602 (2013).

Teissier, J., Barfuss, A., Appel, P., Neu, E. & Maletinsky, P. Strain coupling of a nitrogen-vacancy center spin to a diamond mechanical oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 020503 (2014).

Ovartchaiyapong, P., Lee, K. W., Myers, B. A. & Jayich, A. C. B. Dynamic strain-mediated coupling of a single diamond spin to a mechanical resonator. Nat. Commun. 5, 4429 (2014).

MacQuarrie, E. R. et al. Coherent control of a nitrogen-vacancy center spin ensemble with a diamond mechanical resonator. Optica 2, 233–238 (2015).

Barfuss, A., Teissier, J., Neu, E., Nunnenkamp, A. & Maletinsky, P. Strong mechanical driving of a single electron spin. Nat. Phys. 11, 820–824 (2015).

MacQuarrie, E. R., Gosavi, T. A., Bhave, S. A. & Fuchs, G. D. Continuous dynamical decoupling of a single diamond nitrogen-vacancy center spin with a mechanical resonator. Phys. Rev. B 92, 224419 (2015).

Golter, D. A., Oo, T., Amezcua, M., Stewart, K. A. & Wang, H. Optomechanical quantum control of a nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 143602 (2016).

Lee, K. W. et al. Strain coupling of a mechanical resonator to a single quantum emitter in diamond. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 034005 (2016).

Burek, M. J. et al. Diamond optomechanical crystals. Optica 3, 1404–1411 (2016).

Khanaliloo, B. et al. Single-crystal diamond nanobeam waveguide optomechanics. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041051 (2015).

Meesala, S. et al. Enhanced strain coupling of nitrogen-vacancy spins to nanoscale diamond cantilevers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 5, 034010 (2016).

Mitchell, M. et al. Single-crystal diamond low-dissipation cavity optomechanics. Optica 3, 963–970 (2016).

Ma, Y., Yin, Z., Huang, P., Yang, W. L. & Du, J. Cooling a mechanical resonator to the quantum regime by heating it. Phys. Rev. A. 94, 053836 (2016).

Lau, H.-K. & Plenio, M. B. Laser cooling of a high-temperature oscillator by a three-level system. Phys. Rev. B 94, 054305 (2016).

Fu, K.-M. C. et al. Observation of the dynamic Jahn-Teller effect in the excited states of nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 256404 (2009).

Kittel, C. & Abrahams, E. Dipolar broadening of magnetic resonance lines in magnetically diluted crystals. Phys. Rev. 90, 238–239 (1953).

Acosta, V. M. et al. Diamonds with a high density of nitrogen-vacancy centers for magnetometry applications. Phys. Rev. B 80, 115202 (2009).

Batalov, A. et al. Low temperature studies of the excited-state structure of negatively charged nitrogen-vacancy color centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 195506 (2009).

Rogers, L. J., McMurtrie, R. L., Sellars, M. J. & Manson, N. B. Time-averaging within the excited state of the nitrogen-vacancy centre in diamond. New J. Phys. 11, 063007 (2009).

Plakhotnik, T., Doherty, M. W. & Manson, N. B. Electron-phonon processes of the nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 92, 081203 (2015).

Fuchs, G. D. et al. Excited-state spectroscopy using single spin manipulation in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 117601 (2008).

Doherty, M. W. et al. The nitrogen-vacancy colour centre in diamond. Phys. Rep 528, 1 (2013).

Fuchs, G. D. et al. Excited-state spin coherence of a single nitrogen-vacancy centre in diamond. Nat. Phys. 6, 668–672 (2010).

Slichter, C. P. in Principles of Magnetic Resonance 3rd edn Springer (1990).

Steiner, M., Neumann, P., Beck, J., Jelezko, F. & Wrachtrup, J. Universal enhancement of the optical readout fidelity of single electron spins at nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 81, 035205 (2010).

Gali, A., Fyta, M. & Kaxiras, E. Ab initio supercell calculations on nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond: electronic structure and hyperfine tensors. Phys. Rev. B 77, 155206 (2008).

Bennett, S. D. et al. Phonon-induced spin-spin interactions in diamond nanostructures: application to spin squeezing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 156402 (2013).

Jaynes, E. T. & Cummings, F. W. Comparison of quantum and semiclassical radiation theories with application to the beam maser. Proc. IEEE 51, 89–109 (1963).

Wilson-Rae, I., Nooshi, N., Dobrindt, J., Kippenberg, T. J. & Zwerger, W. Cavity-assisted backaction cooling of mechanical resonators. New J. Phys. 10, 095007 (2008).

Tavis, M. & Cummings, F. W. Exact solution for an N-molecule-radiation-field Hamiltonian. Phys. Rev 170, 379–384 (1968).

Garraway, B. M. The Dicke model in quantum optics: Dicke model revisited. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 369, 1137–1155 (2011).

Fuchs, G. D., Falk, A. L., Dobrovitski, V. V. & Awschalom, D. D. Spin coherence during optical excitation of a single nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 157602 (2012).

Robledo, L., Bernien, H., van der Sar, T. & Hanson, R. Spin dynamics in the optical cycle of single nitrogen-vacancy centres in diamond. New J. Phys. 13, 025013 (2011).

Schuster, D. I. et al. High-cooperativity coupling of electron-spin ensembles to superconducting cavities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 140501 (2010).

Jacques, V. et al. Dynamic polarization of single nuclear spins by optical pumping of nitrogen-vacancy color centers in diamond at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 057403 (2009).

Tabrizian, R., Rais-Zadeh, M. & Ayazi, F. Effect of phonon interactions on limiting the f.Q product of micromechanical resonators. in Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems Conference. TRANSDUCERS 2009, 2131–2134 (IEEE, 2009).

Jaehne, K., Hammerer, K. & Wallquist, M. Ground-state cooling of a nanomechanical resonator via a Cooper-pair box qubit. N. J. Phys. 10, 095019 (2008).

Otten, M. et al. Entanglement of two, three, or four plasmonically coupled quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 92, 125432 (2015).

Saad, Y. & Schultz, M. GMRES: a generalized minimal residual algorithm for solving nonsymmetric linear systems. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 7, 856–869 (1986).

Balay, S. et al. PETSc users manual. Tech. Rep. ANL-95/11 - Revision 3.7, (Argonne National Laboratory, 2016).

Balay, S., Gropp, W. D., McInnes, L. C. & Smith, B. F. in Modern Software Tools in Scientific Computing (eds Arge, E., Bruaset, A. M. & Langtangen, H. P.), 163–202 (Birkhäuser Press, 1997).

Choi, S. et al. Depolarization dynamics in a strongly interacting solid-state spin ensemble. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1608.05471 (2016).

Baranov, P. G. et al. Enormously high concentrations of fluorescent nitrogen-vacancy centers fabricated by sintering of detonation nanodiamonds. Small 7, 1533–1537 (2011).

Wee, T.-L. et al. Two-photon excited fluorescence of nitrogen-vacancy centers in proton-irradiated type Ib diamond. J. Phys. Chem. A 111, 9379–9386 (2007).

Tao, Y., Boss, J. M., Moores, B. A. & Degen, C. L. Single-crystal diamond nanomechanical resonators with quality factors exceeding one million. Nat. Commun. 5, 3638 (2014).

Smith, M. J. A., Angel, B. R. & Emmons, R. G. Distribution of substitutional nitrogen donors in synthetic diamonds. Nature 210, 692–694 (1966).

Safavi-Naeini, A. H. et al. Observation of quantum motion of a nanomechanical resonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 033602 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Research support was provided by the Office of Naval Research (ONR) (Grant N000141410812). Device fabrication was performed in part at the Cornell NanoScale Science and Technology Facility, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure, which is supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant ECCS-15420819), and at the Cornell Center for Materials Research Shared Facilities which are supported through the NSF MRSEC program (DMR-1120296). Numerical simulations were performed in part at the Centre for Nanoscale Materials, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. This research used resources of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC05-00OR22725.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.R.M. and G.D.F. developed the concept and procedure for the experiment and the proposed cooling protocol. E.R.M. performed the experiments and analysed the data. E.R.M., M.O., S.K.G. and G.D.F. developed the toy model treatment of the proposed cooling protocol. M.O. and S.K.G. developed and performed the numerical simulations that validate the toy model treatment of the cooling protocol. E.R.M., M.O, S.K.G. and G.D.F. prepared the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Notes and Supplementary References (PDF 870 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

MacQuarrie, E., Otten, M., Gray, S. et al. Cooling a mechanical resonator with nitrogen-vacancy centres using a room temperature excited state spin–strain interaction. Nat Commun 8, 14358 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14358

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14358

This article is cited by

-

Intracavity-squeezed cooling in the three-cavity optomechanical system

Quantum Information Processing (2023)

-

Excited-state spin-resonance spectroscopy of V\({}_{{{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}}}^{-}\) defect centers in hexagonal boron nitride

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Acoustic cavities in 2D heterostructures

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Spin–phonon interactions in silicon carbide addressed by Gaussian acoustics

Nature Physics (2019)

-

Accounting for errors in quantum algorithms via individual error reduction

npj Quantum Information (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.