Abstract

Armadillo repeat containing 5 (ARMC5) is a cytosolic protein with no enzymatic activities. Little is known about its function and mechanisms of action, except that gene mutations are associated with risks of primary macronodular adrenal gland hyperplasia. Here we map Armc5 expression by in situ hybridization, and generate Armc5 knockout mice, which are small in body size. Armc5 knockout mice have compromised T-cell proliferation and differentiation into Th1 and Th17 cells, increased T-cell apoptosis, reduced severity of experimental autoimmune encephalitis, and defective immune responses to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. These mice also develop adrenal gland hyperplasia in old age. Yeast 2-hybrid assays identify 16 ARMC5-binding partners. Together these data indicate that ARMC5 is crucial in fetal development, T-cell function and adrenal gland growth homeostasis, and that the functions of ARMC5 probably depend on interaction with multiple signalling pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The gene Armadillo was first identified in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster as a gene controlling larval segmentation with morphological similarity to armadillos1,2. β-Catenin is the human and mouse orthologue of fruit fly Armadillo3. Armadillo/β-catenin protein contains 13 and 12 conserved armadillo (ARM) repeats, respectively: each repeat is about 40 amino acid (aa) long and consists of 3 α-helices4. Multiple repeats form an ARM domain which has a groove for binding various other proteins in its tertiary structure5. More than 240 proteins, from yeasts to humans, are known to contain an ARM domain6,7. Although β-catenin is believed to interact with and regulate cytoskeleton function, its roles and those of ARM domain-containing proteins, in general, are very versatile in cell biology, including cytoskeleton organization8, cell-cell interactions9, protein nuclear import10, degradation11 and folding12, cell signalling/sensing13,14,15, molecular chaperoning16, cell invasion/mobility/migration17, transcription control18, cell division/proliferation19 and spindle formation20, to name some of them.

At the tissue and organ levels, ARM domain-containing proteins are involved in T-cell development21, lung morphogenesis22, limb dorsal-ventral axis formation23, neural tube development24, osteoblast/chondrocyte switch25, synovial joint formation26, adrenal gland cortex development27 and tumour suppression28.

Due to the very diverse functions of ARM domain-containing proteins, it is challenging to predict their mechanisms of action. Indeed, these aspects of many ARM domain-containing proteins remain undeciphered, and quite a number of them are given the name ARMC (ARM repeat-containing), followed by Arabic numbers (for example, ARMC1, 2, 3 and so on). ARMC5 is one such protein.

Human and mouse ARMC5 proteins share 90% aa sequence homology and have similar structures29,30. Mouse ARMC5 is 926 aa in length and contains 7 ARM repeats. A BTB/POZ domain towards its C-terminus is responsible for dimerization or trimerization31,32,33. Several groups reported in 2013 and 2014 that ARMC5 gene mutations are associated with primary macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (PMAH) and Cushing’s syndrome34,35,36. Assié et al.34 demonstrated that no viable HeLa cells could be obtained when they were stably transfected with ARMC5-expressing vectors. They suggested that the default function of wild-type (WT) ARMC5 is the suppression of cell proliferation or promotion of apoptosis, which might explain the adrenal cortex hyperplasia seen in patients with ARMC mutations. No other reports on ARMC5 function and mechanisms of action are available in the literature.

In the present work, we have studied the tissue-specific expression of Armc5. We have generated Armc5 gene knockout (KO) mice, and revealed that ARMC5 is vital in development and immune responses. We also show that aged KO mice develop adrenal gland hyperplasia. We have identified a group of ARMC5-interacting proteins by yeast 2-hybrid (Y2H) assay, paving the way for further mechanistic and functional investigations of ARMC5.

Results

Armc5 expression in mice and T cells

Armc5 mRNA expression was analysed by in situ hybridization (ISH) in adult WT mice. Haematoxylin/eosin staining of a consecutive sagittal whole body section preceded ISH (Fig. 1a, upper panel). Armc5 expression, based on anti-sense riboprobe hybridization (Fig. 1a, middle panel), was high in the thymus, stomach, bone marrow and lymphatic tissues (including lymph nodes and intestinal wall). The hybridization was also apparent in the adrenal gland and skin. Some hybridization occurred in brain structures, with noticeable levels found in the cerebellum. Control hybridization with sense (S) riboprobes revealed a faint nonspecific background (Fig. 1a, bottom panel).

(a) Armc5 expression in adult mouse using whole-body sections. Upper panel: H/E staining; middle and bottom panels: dark field X-ray film autography with anti-sense (AS) cRNA or sense (S) cRNA as probes, respectively. Bar=1 cm. AG: adrenal gland; B: bone; BM: bone marrow; Cb: cerebellum; K: kidney; Lint: large intestine; LT: lymphatic tissue; Sk: skin; ST: stomach; Th: thymus; VB: vertebrae. (b) Armc5 expression in the adult thymus. Upper row: dark field X-ray film autography; lower row: bright field emulsion autoradiography; left column: anti-sense probe; right column: sense probe. Bars=2 mm and 20 μm. Cx: cortex; Me: medulla. (c) Armc5 expression in the adult spleen. Upper and middle panels: dark field X-ray film autography, with anti-sense and sense probes, respectively; bottom panel: bright field emulsion autoradiography. Bars=2 mm and 20 μm. WP: white pulp; RP: red pulp; CAr: central artery; Cp: capillary. (d) Armc5 mRNA in mouse spleen CD4 and CD8 cells measured by RT-qPCR. Experiments were performed three times. The results of representative experiments are shown. To facilitate comparison, normalized ratios of Armc5 versus β-actin signals (means±s.e.m.) are presented; the 0-h signal ratio of each experiment is considered as 1. (e) ARMC5 subcellular localization in L cells was detected immunofluorescence. L cells were transfected with HA-tagged mouse ARMC5-expressing construct or an empty vector, as indicated. (f) Phase contract micrographs of views in (e). The experiments were conducted three times, and micrographs of a representative experiment are shown. Scale bar: 5 μm.

At the anatomical level, Armc5 expression was high in the thymus cortex (Fig. 1b, upper left panel). This was confirmed at the microscopic level (Fig. 1b, bottom left panel). The higher Armc5 signals in the cortex than in the medulla were due to higher cell density in the former. Sense riboprobes detected little background noise (Fig. 1b, right column). Based on reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) results, thymic stroma cells (including epithelial cells) had Armc5 expression similar to that of thymocytes (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Further, there was no significant difference in Armc5 expression among thymocyte subpopulations (CD4/CD8 double-negative (DN) 1–4, CD4/CD8 double-positive (DP), and CD4- or CD8-single-positive (SP); Supplementary Fig. 1b,c; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2a), and between naive and memory spleen T cells (Supplementary Fig. 1d; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2b).

Moderately intense Armc5 labelling was apparent in spleen white pulp but not in red pulp (Fig. 1c, upper panel). At the microscopic level, small groups of cells in WP displayed Armc5 signals (Fig. 1c bottom panel). Sense riboprobes detected no signals (Fig. 1c middle panel).

Armc5 mRNA expression was induced rapidly in CD4 cells in 2 h after CD3ɛ plus CD28 stimulation, then subsided and remained low between 24 and 72 h post-activation (Fig. 1d, upper row). CD8 T cells had less Armc5 induction and the levels remained low between 24 and 72 h (Fig. 1d, lower row).

ARMC5 was mainly a cytosolic protein, as it was detected in the cytoplasm of L cells transiently transfected with a mouse ARMC5 expression construct (Fig. 1e,f).

Generation of Armc5 KO mice

We generated Armc5 KO mice to understand the biological roles of ARMC5 in general and T-cell-mediated immune responses in particular. Our targeting strategy is illustrated (Fig. 2a). Germline transmission was confirmed by Southern blotting of tail DNA (Supplementary Fig. 3). With the 5′ end probe, the WT allele after EcoRV digestion gave a 9.3-kb band, and the KO allele, a 6.6-kb band (Supplementary Fig. 3, upper panel). With the 3′ end probe, the WT allele after HindIII digestion presented a 12.5-kb band, and the KO allele, an 8.7-kb band (Supplementary Fig. 3, lower panel). WT (mice 3 and 7) and heterozygous mice (mice 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6) were thus identified. Mouse 1 in the original 129/sv × C57BL/6J background was backcrossed to different genetic backgrounds for experimentation, as detailed below.

(a) Armc5 KO mice were generated by targeted gene deletion. The targeting strategy is depicted. Red squares on 5′ and 3′ sides of the mouse Armc5 WT genomic sequence represent sequences serving as probes for genotyping by Southern blotting. (b) Armc5 mRNA deletion in KO mice was confirmed by RT-qPCR. The results are expressed as normalized ratios (means±s.e.m.) of Armc5 versus β-actin mRNA signals. The values from WT mice are considered as 1. Experiments were conducted more than three times, and representative results are reported.

Armc5 deletion of KO mice at the mRNA level in spleen T cells, thymocytes, lymph nodes, brain and adrenal glands was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Fig. 2b).

General phenotype of Armc5 KO mice

When Armc5 KO mice were in the C57BL/6J × 129/sv F1 background, only about 10% live KO pups were delivered in a heterozygous × heterozygous mating strategy, below the expected 25% Mendelian rate. After F1 mice were backcrossed to C57BL/6 for five or more generations, no KO pups could be produced, nor were live KO pups born after the mice were backcrossed eight generations to the 129/sv background. This suggested that Armc5 deletion caused embryonic lethality, with its severity depending on genetic background of the mice: embryonic lethality became more severe with higher degrees of genetic background purity. KO mice in the C57BL/6J × 129/sv F1 background were studied in subsequent experiments.

KO embryos were smaller than WT controls at embryonic day 14 (Fig. 3a). These KO pups were smaller at age 8–12 weeks (Fig. 3b). Body weight was significantly lower in KO and WT mice at age 4 and 8 weeks than in their WT littermates (Fig. 3c). Both male and female KO mice weighed only about 60% as much as WT controls.

(a) Representative photos of WT, HT, KO fetuses on embryonic day 14. (b) Representative photos of adult KO and WT littermates. Left panel: males (8 weeks old); right panel: females (12 weeks old). (c) Body weight (means±s.e.m.) of Armc5 KO and WT littermates at age 4 and 8 weeks. Mouse numbers (n) per group are indicated. *p<0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). (d) Morphology (upper panel) and histology (lower panel, HE staining) of adrenal glands from old KO mice (19 months old). Magnification: × 5. Scale bar: 500 μm. (e) Serum glucocorticoid levels in old KO mice. Means±s.e.m. of serum glucocorticoids in old KO and WT mice are shown. Age of each group (means±s.e.m.) and mouse number per group are indicated. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.

We examined serum growth hormone levels because of growth retardation in KO mice, but no significant difference was found between them and their WT counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 4).

ARMC5 gene mutations have been reported to be linked with PMAH and Cushing’s syndrome34. However, KO mice presented normal adrenal gland size and histology (Supplementary Fig. 5) and serum glucocorticoid levels (Supplementary Fig. 6) in young age (less than age 5 months). In old age (>15 months), grossly, KO mice showed enlarged adrenal glands without apparent nodular structure, and histologically, there is no identifiable nodular hyperplasia (Fig. 3d). Serum glucocorticoid levels were significantly increased in aged KO mice (Fig. 3e), supporting the notion that the adrenal gland hyperplasia is of cortex in nature. It is to be noted that the mice were killed between 12:30 and 13:30, and their blood was harvested for the measurement of glucocorticoids, whose secretion is at the nadir at this time point. The moderate but significant increase of glucocorticoid levels in the KO mice is reminiscent of human PMAH, in which the increase of glucocorticoid levels is not drastic and is caused by the large mass of the adrenal gland, while on a per cell basis, the secretion is reduced34.

Armc5 KO phenotype in lymphoid organs and T cells

Thymus (Supplementary Fig. 7a) and spleen (Supplementary Fig. 7b) weight and cellularity were not significantly different in KO and WT mice. Moreover, thymocyte sub-populations (CD4+CD8+ DP, CD4+ SP and CD8+ SP cells) in the KO and WT thymus were comparable (Supplementary Fig. 7c), as were spleen lymphocyte subpopulations (Thy1.2+ T cells versus B220+ B cells; CD4+ versus CD8+ T cells; Supplementary Fig. 7d).

Despite seemingly normal T-cell development in KO mice, T-cell proliferation triggered by anti-CD3ɛ was compromised in both CD4 and CD8 cells (Fig. 4a, left and middle panels; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2c). It is to be noted that activation markers CD25 and CD69 shortly after CD3 stimulation were drastically upregulated and were always comparable between WT and KO T cells (Supplementary Fig. 8). The proliferation rate of KO B cells was also lower (Fig. 4a, right panel; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2d). Cell cycle analysis revealed that G1/S progression was compromised in KO T cells (Fig. 4b; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2e). We also demonstrated that KO T cells (gated on CD4+ plus CD8+ cells) presented increased FasL-triggered apoptosis (Fig. 4c; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2f).

(a) Proliferation of spleen CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and B220+ B cells from WT and KO mice according to CFSE staining. CFSE intensity was ascertained by flow cytometry. Experiments were conducted independently 4–6 times. Representative histograms are shown. (b) Cell cycle progression of spleen T cells from WT and KO mice. The percentages of cells in G1, S and G2 phases are indicated. Experiments were conducted independently three times. Representative histograms are shown. (c) Apoptosis of WT and KO spleen T cells (gated on CD4+ plus CD8+ cells) upon FasL stimulation was determined by their annexin V expression according to flow cytometry. Experiments were conducted independently three times. Representative histograms are shown.

Naive KO CD4 cells cultured under Th1 and Th17 conditions manifested reduced proliferation, as expected (Fig. 5a; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2g). The differentiation of naive CD4 cells into Th1 and Th17 cells was defective (Fig. 5b; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2g), since the percentages of Th1 or Th17 cells were decreased among CD4 cells, which had already proliferated. The expression of transcription factors T-bet and RORγt—essential for Th1 and Th17 differentiation, respectively—were normal in KO CD4 cells cultured under Th1 and Th17 differentiation conditions (Fig. 5c,d), when gated on either total CD4 cells or on those already differentiated cells (IFN-γ+ or IL-17+ cells), suggesting that the defective differentiation is not caused by a lack of these transcription factors.

(a) Proliferation of WT and KO naive spleen CD4 cells under Th1 and Th17 conditions was assessed based on CFSE content according to flow cytometry. Experiments were conducted three times, and representative histograms are shown. Grey peaks represent the CFSE content of CD4 cells at day 0. (b) These cells’ differentiation into Th1 and Th17 cells was also determined by flow cytometry according to intracellular IFN-γ and IL-17 positivity (gated on total CD4+). Representative dot plots are shown in the left panel. Means±s.e.m. of data from three experiments are presented as bar graphs in the right panel. Mouse numbers (n) per group are indicated. P values are reported in the bar graphs (two-tailed Student’s t-test). (c,d) T-bet and RORγt expression in CD4 cells cultured under Th1 and Th17 conditions or in IFNγ+ or IL-17+ cells was determined by flow cytometry. Experiments were conducted three times. Representative histograms are shown. (e) Th1 and Th17 differentiation of naive spleen CD4 cells (CD45.2 single-positive) derived from WT and KO donors in chimeric mice was analysed by flow cytometry based on their intracellular IFN-γ and IL-17 expression. Representative dot plots are shown in the left panel. Means±s.e.m. of data from three experiments are presented as bar graphs in the right panel. Mouse numbers (n) per group are indicated. p values are reported in the bar graphs (two-tailed Student’s t-test).

As for humoral immune responses, KO serum IgG levels were comparable to those of WT controls (Supplementary Fig. 9).

We generated chimeric mice by transplanting KO and WT fetal liver cells in the C57BL/6J × 129/sv F1 background (CD45.2+ SP) into lethally irradiated C57BL/6J × C57B6.SJL F1 mice (CD45.1+CD45.2+ DP). Peripheral white blood cells of the recipients were analysed by flow cytometry 8 weeks after transplantation, and recipients of similar degrees of KO and WT chimerism were paired for experimentation. Typically, about 80–85% of peripheral white blood cells were of donor origin (CD45.2+ SP), and 12–15%, of recipient origin (CD45.1+CD45.2+ DP). In spleen Thy1.2+ total T cells, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, 60–70% were of donor origin, and 30–35% of recipient origin (Supplementary Fig. 10). Unlike in Armc5 KO mice, KO T cells in chimeras were developed in a WT environment, devoid of influence by putatively unknown factors which might exist in the total KO environment and have aberrant effects on T-cell development.

We showed that donor-derived KO naive CD4 cells were defective in differentiating into Th1 cells (Fig. 5e; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2h), similar to CD4 cells from unmanipulated, naive KO mice (Fig. 5b). The KO Th17 cell differentiation in this model was also compromised, although did not reach statistical significance, probably due to an inadequate sample size (Fig. 5e).

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in KO mice

To understand the role of ARMC5 in in vivo T-cell immune responses, particularly CD4-mediated immune responses, we induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in Armc5 WT and KO mice. As shown in Fig. 6a, WT mice started to manifest clinical signs of EAE on day 13.2±1.30 (means±s.e.m.) after immunization, and their symptoms peaked on day 23. The onset of clinical symptoms in KO mice was delayed by about 7 days, and their maximum disease score was significantly lower than that of WT controls (P<0.01, two-tailed Student’s t-test) after day 18. Disease incidence was lower in KO mice between days 15 and 18, although it reached 100% in both KO and WT groups after day 28 (Fig. 6b). A trend towards less body weight loss in KO mice was noted after EAE induction compared to WT controls, but statistically significant difference was reached only on day 22 (Fig. 6c).

(a) Means±s.e.m. of EAE clinical scores of KO and WT mice. *P<0.05 (two-tailed Student's t-test). (b) EAE incidence in KO and WT mice. *P<0.05 (chi-square test). (c) Means±s.e.m. of body weight of KO and WT mice during EAE induction. Body weight of mice on day 10 post-immunization was considered as 100%. *P<0.05 (two-tailed Student's t-test). (d) Means±s.e.m. of cellularity in draining LN and of cells infiltrating the CNS of mice 14 days after MOG immunization. Mouse numbers (n) and P values (paired two-tailed Student's t-test) are indicated. (e,f) Cytokine-producing cells among CD4 cells from draining LN (e) and CNS (f) on days 13–18 after MOG immunization. Left panels: representative dot plots; right panel: bar graphs (means±s.e.m.) summarizing all the results, with mouse numbers and P values (two-tailed Student's t-test) indicated. (g) HE (left column) or Luxol Fast Blue (right column) staining of spinal cords 30 days after MOG immunization. Asterisks indicate cell infiltration. Arrows point to demyelination. (h) Means±s.e.m. of mononuclear cell infiltration scores, demyelination scores and total pathological scores, which is the sum of the first two scores. Mouse numbers (n) and P values (two-tailed Student's t-test) are indicated. (i) Treg cells in naive KO mice on day 17 during EAE induction. Left panel: representative dot plots; right panel: means±s.e.m. of data from three experiments. NS: not significant (two-tailed Student's t-test).

KO mice had significantly fewer cells in their draining lymph node (LN) and fewer infiltrating mononuclear cells in the brain and spinal cords on day 14 after myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) immunization compared to WT controls (Fig. 6d). After ex vivo phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)/ionomycin stimulation, the percentage of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ+) CD4 cells among total CD4 cells from the LN of KO mice was significantly lower than that of WT mice (6.2 versus 15.4%), although the percentage of IL-17+ cells among CD4 cells was similar in KO and WT draining LN (Fig. 6e). The percentages of IFN-γ+ and IL-17+ populations in CD4+ T cells from the central nervous system (CNS) of KO mice were significantly lower after ex vivo PMA/ionomycin stimulation than in WT mice (Fig. 6f).

Histologically, spinal cords from KO animals on day 30 after MOG immunization showed less severe mononuclear cell infiltration and demyelination, according to HE and Luxol Fast Blue staining, respectively, compared to their WT counterparts (Fig. 6g). Histological data from four KO and five WT spinal cords are summarized (Fig. 6h). Mononuclear cell infiltration in KO spinal cords was significantly lower than in WT controls. Although demyelination in the former was also lower, it did not reach statistical significance. However, combined pathological scores, which included degrees of both mononuclear cell infiltration and demyelination, were significantly lower in KO mice. We did not observe changes in the percentages of Treg cells in the spleen of naive KO mice or in the draining LN of KO mice on day 17 during EAE induction, compared to WT controls (Fig. 6i; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2i). Therefore, it is unlikely that Treg cells are implicated in reduced EAE severity in KO mice.

To exclude the possible influence of the Armc5 KO background on the immune system of KO mice, EAE was also induced in chimeras transplanted with fetal liver cells from Armc5 WT and KO embryos on days 13–15. Overall, KO chimeras still displayed a lower degree of EAE than WT chimeras, but the difference was not as dramatic as in real KO versus WT mice. The onset of clinical symptoms in KO chimeras occurred 2.5 days (mean) later than in WT chimeras. KO chimera clinical scores tended to be lower than those of WT mice, but were only significantly different between days 12 and 14 (Fig. 7a). EAE incidence was significantly lower on days 11, 12 and 14 after immunization (Fig. 7b). A trend of less body weight loss was noted in KO chimeric mice, although no statistical difference was apparent between the KO and WT groups (Fig. 7c). When stimulated ex vivo by PMA/ionomycin, the percentage of KO donor-derived IFN-γ+ CD4 cells among total KO donor-derived CD4 cells from the CNS was significantly lower than in WT controls (Fig. 7d; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2h), as was the case in real KO mice. However, there was no significant difference between the percentage of KO donor-derived IL-17+ CD4 cells among total KO donor-derived CD4 cells and that of WT mice. The reduced degree of difference in EAE manifestation in KO versus WT chimeras, compared to that in real KO versus WT mice, was not unexpected, as KO chimeras contained about 30% recipient-derived T cells, which were fully immuno-competent WT T cells.

(a) Means±s.e.m. of EAE clinical scores of chimeric mice.*P<0.05 (two-tailed Student's t-test). (b) EAE incidence in chimeric mice. *P<0.05 (chi-square test). (c) Means±s.e.m. of body weight of chimeric mice with body weight on day 10 after MOG immunization considered as 100%. No significant difference is found (two-tailed Student's t-test). (d) Cytokine-producing donor-derived CD4 cells in the CNS of chimeric mice on day 14 after MOG immunization. Left panel: representative dot plots; right panel: summary (means±s.e.m.) of all the results, with mouse numbers (n) and P-values (paired two-tailed Student's t-test) indicated.

Antiviral immune responses in KO mice

CD8 T-cell-mediated immune responses play a critical role against lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection. Therefore, we assessed KO CD8+ T-cell functions in LCMV infection. Eight days after mice were infected with LCMV (strain WE), absolute numbers of WT CD8+ T cells but not CD4+ T cells increased significantly (Fig. 8a; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2j). LCMV tetramer staining showed that both the number of gp33–41−, np396–405− and gp276–286-specific CD8 T cells per spleen and their percentage among total spleen CD8+ T cells were significantly lower in KO than in WT mice (Fig. 8b–d; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2k), suggesting compromised CD8 cell clonal expansion after viral Ag stimulation in KO mice.

(a) Spleen CD8 cell numbers in KO mice on day 8 after LCMV infection as determined by flow cytometry. Mice number (n), means±s.e.m. and P values (two-tailed Student's t-test) are indicated. (b) Virus-specific spleen CD8 cells in KO mice on day 8 post-LCMV infection according to flow cytometry. Representative dot plots are shown. (c) Means±s.e.m. of percentages of gp33–41, np396–405 and gp276–286 tetramer-positive cells among spleen CD8 cells from all the results are presented. Numbers (n) of mice per group and P values (two-tailed Student's t-test) are indicated. (d) Means±s.e.m. of absolute numbers of gp33–41, np396–405 and gp276–286 tetramer-positive CD8 cells in the KO and WT mouse spleens on day 8 post infection. Numbers (n) of mice per group and P values (two-tailed Student's t-test) are indicated. (e,f) Memory and effector CD8 cell maturation in LCMV-infected WT and KO mice on day 8 post LCMV infection. KLRG1loCD127hi cells are considered as memory precursor effector cells (MPEC), and KLRG1hiCD127lo cells as short-lived effector cells (SLEC). Means±s.e.m. are presented. Numbers (n) of mice per group and P values (two-tailed Student's t-test) are indicated (e). Representative dot plots are shown (f). (g) On day 8 post infection, total gp33–41 np396–405 and gp276–286 tetramer-positive CD8 cells in KO and WT mouse spleen were assessed for activation markers. Means±s.e.m. are presented. Numbers (n) of mice per group and P values (two-tailed Student's t-test) are indicated.

After infection, CD8 cells develop into KLRG1hiCD127lo short-lived effector cells (SLEC) and KLRG1loCD127med memory precursor effector cells (MPEC)35. In KO mice, 8 days after LCMV infection, the percentage of SLEC among CD8 T cells was significantly lower (Fig. 8e,f; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2k), indicating defective anti-virus effector cell development. At the same time, MPEC percentage among CD8 T cells was increased in KO mice. The significance of this finding is not clear at present, although the percentage of CD62LloCD44hi effector memory cells among total CD8 cells (Supplementary Fig. 11a) and LCMV subdominant epitope (np396–405 and gp276–286)-specific CD8 T cells (Fig. 8g; gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2k) in KO mice was reduced.

We next examined the presence of LCMV-specific, cytokine-producing splenic T cells in virus-infected mice. As seen in Fig. 9a (gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 2k), the absolute number of gp33–41-specific TNF-α-positive CD8+ T cells, IFN-γ-positive CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ/TNF-α DP CD8 T cells per spleen was significantly lower in KO than in WT mice 8 days post-infection. Significantly lower percentages of gp33–41-specific, IFN-γ-positive CD8 T cells and IFN-γ/TNF-α DP CD8+ T cells, but not TNF-α-positive CD8 T cells, among total spleen CD8 T cells, were found in KO spleens (Fig. 9b, representative dot plots shown in Supplementary Fig. 11c). Similarly decreased numbers and percentages of LCMV-specific cytokine-producing cells were observed in the CD4 cell population, although the reduction was of lower magnitude compared to those in the CD8 cells (Fig. 9c; representative dot plots shown in Supplementary Fig. 12d).

(a) Absolute number of virus-specific, cytokine-producing CD8 cells. (b,c) Percentages of virus-specific, cytokine-producing cells among CD8 cells (b) and CD4 cells (c) on day 8 post LCMV infection. Means±s.e.m. of data are shown. Mouse numbers (n) per group and P values (two-tailed Student's t-test) are indicated. (d) Means±s.e.m. of percentages of gp33–41-specific CD107a+GranB+ CD8 T cells on day 8 post LCMV infection. Mouse numbers (n) per group and P values (two-tailed Student's t-test) are indicated. (e) Means±s.e.m. of viral titres in the kidney, liver and spleen on day 8 post LCMV infection. Mouse numbers (n) per group and P values (two-tailed Student's t-test) are indicated.

In addition, lower percentages of gp33–41-specific CD107a+GranB+ T cells among total CD8+ T cells were observed in KO spleen (Fig. 9d; representative dot plots shown in Supplementary Fig. 11f), implying the presence of fewer functional virus-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in KO mice. Virus titers in the kidneys, liver and spleen were significantly higher in KO mice 8 days post-LCMV infection, suggesting compromised virus clearance (Fig. 9e).

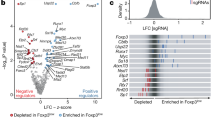

Identification of ARMC5-binding proteins by Y2H assay

ARMC5 has no enzymatic activity: its functions depend on interaction with molecules involved in different signalling pathways. To identify ARMC5-binding proteins, we conducted Y2H assays with human ARMC5 protein (Glu30-Ala935) as bait, and a human primary thymocyte cDNA expression library as prey. The binding proteins were given Predicted Biological Confidence scores36, and 16 proteins with scores between A and D (‘A’ having the highest confidence of binding) are found (Table 1), if their coding sequences are in-frame and have no in-frame stop codons. A complete list of binding proteins identified by Y2H assay and a map showing the interaction regions between ARMC5 and its binding partners are provided in the Supplementary Materials section (Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Fig. 12).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that Armc5 mRNA was highly expressed in the thymus and adrenal glands. Its deletion led to small body size in mice and compromised T-cell proliferation and differentiation. KO mice presented defective induction of EAE and anti-LCMV immune responses. KO mice developed adrenal gland hyperplasia in old age. ARMC5 is a protein without enzymatic activity. Our Y2H assays identified 16 candidate ARMC5-binding proteins potentially capable of linking ARMC5 to different signalling pathways involved in cell cycling and apoptosis.

Armc5 expression at the mRNA level was upregulated immediately (within 2 h) after CD4 T-cell activation by T cell receptor (TCR) ligation and less so and at a slower pace in CD8 cells. Its expression level then declined in the following days (Fig. 1d). Armc5 expression in CD4 cells cultured under Th1 or Th17 conditions after 1 day remained low (Supplementary Fig. 13), and was not influenced by the presence of different lymphokines, such as IL-2, IL-6 or TGF-β1 (Supplementary Fig. 14). Armc5 mRNA expression in CD8 cells 8 days after LCMV infection was significantly lower than in naive CD8 cells (Supplementary Fig. 15). These data suggest that this molecule is probably important in the early stage of TCR-triggered T-cell activation to prepare cells for entry into the cell cycle. This notion is supported by cell cycle analysis, which revealed that KO T cells were compromised in G1/S progression (Fig. 4b).

We found reduced numbers of infiltrating T cells as well as Th1 (IFN-γ+) and Th17 (IL-17+) cells in the CNS of KO EAE mice compared to WT EAE controls. Such decreases were likely responsible for the diminished EAE manifestations in KO mice. Reduced CNS lymphocyte infiltration could be caused by compromised clonal expansion/differentiation of T cells in the periphery, defective migration of such cells into the CNS, reduced expansion/differentiation of these cells in the CNS, decreased apoptosis of cells in the periphery and CNS, or all of the above. Defective KO T-cell clonal expansion/differentiation in the periphery was apparent according to our in vitro and in vivo results (Figs 4 and 7b), but whether this is also the case in the CNS remains to be studied.

We demonstrated that ARMC5 deletion resulted in comprised TCR-stimulated proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vitro and LCMV-specific CD8+ T-cell clonal expansion in vivo. Moreover, we observed a significant reduction in SLECs in KO mice following LCMV infection while MPECs were increased. Taken together, these results suggest a function for ARMC5 in promoting T-cell growth following TCR engagement possibly by regulating activation threshold levels; this provides a potential explanation for the observed increase in T-cell death following FasL engagement (Fig. 4c) in KO mice. It is possible that augmented apoptosis also plays a role in compromised Th1 and Th17 development from naive KO CD4 cells. However, ARMC5 mutations lead to PMAH in humans and diffuse adrenal gland hyperplasia in mice (Fig. 3d), indicating that it has a default function of repressing adrenal cell proliferation, or a default pro-apoptotic function, or both. Indeed, an in vitro study of the human adrenal gland cell line H295R revealed that ARMC5 overexpression culminates in apoptosis34, supporting its putative default anti-apoptotic function in adrenal glands. Dichotomous functions of ARMC5 in T cells versus adrenal glands indicate its tissue- or context-specificity, likely due to ARMC5’s association with different binding partners. In different types of cells, ARMC5 might preferentially bind to a certain partner, depending on its relative abundance in a given cell type or cell status. Consequently, the default function of ARMC5 in certain types of cells or cells with a given status could be either pro- or anti-proliferation, pro- or anti-apoptosis, or neutral. It could explain the different phenotypes seen in T cells versus adrenal glands, in terms of proliferation and apoptosis. It could also explain the obvious dilemma that KO T-cell development in the thymus, which involves fast thymocyte proliferation, is normal, but TCR-stimulated T-cell proliferation/differentiation and virus-induced T-cell clonal expansion are defective in KO mice.

Although B cells were not the focus of this study, we did demonstrate that KO B cells were compromised in proliferation triggered by BCR ligation. Although KO mice had normal serum IgG levels, it is possible that, under strenuous conditions, KO mice might manifest defective humoral immune responses.

Based on the functional results of our ARMC5 study, those from PMAH investigations, and protein association information from Y2H assays, we propose the following speculative model of ARMC5 mechanisms of action. ARMC5 transcription and protein expression are increased when the cells are activated. Induced ARMC5 forms dimers (or multimers) in cytosol. Such dimers are able to interact with different molecules in pathways regulating cell cycling and apoptosis, for example, CUL3 for cell cycling and DAPK1 for apoptosis. Therefore, depending on the relative abundance of binding proteins in different cell types and cells in different states, ARMC5 may interact preferentially with one or the other, leading to opposite functions in regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis. It should be noted that list of associating proteins might expand, pending further verification.

In summary, we demonstrated that ARMC5 has vital functions in fetal development, T-cell biology, immune responses and adrenal gland biology. We have created Armc5 KO mice as the first animal model of a rare human disease: PMAH. Our mechanistic study to identify ARMC5-binding partners has laid the groundwork for further elucidation of ARMC5’s mechanisms of action. With a better understanding of these mechanisms, this molecule may be deployed as a therapeutic target in immune and endocrine disorders.

Methods

ISH

To localize Armc5 mRNA, 1526-bp (starting from GATATC to the end) mouse Armc5 cDNA (GenBank: BC032200, cDNA clone MGC: 36606) in pSPORT1 was employed as template for S and AS riboprobe synthesis, with SP6 and T7 RNA polymerase for both 35S-UTP and 35S-CTP incorporation37.

Tissues from WT mice were frozen in −35 °C isopentane and kept at −80 °C until they were sectioned. ISH, X-ray and emulsion autoradiography focused on 10-μm thick cryostat-cut sections. Briefly, overnight hybridization at 55 °C was followed by extensive washing and digestion with RNase to eliminate non-specifically bound probes. Anatomical level images of ISH were generated using X-Ray film autoradiography after 4 days’ exposure. Microscopical level ISH was produced by dipping sections in NTB-2 photographic emulsion (Kodak). The exposure time was 28 days. The autoradiography labelling was revealed by D19 Developer (Kodak) and fixation with 35% sodium thiosulphate. Slides were left unstained or slightly stained with HE (ref. 37).

RT-qPCR

Armc5 mRNA in thymocytes, T cells, B cells and tissues from KO and WT mice was measured by RT-qPCR. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then reverse-transcribed with Superscript II reverse-transcriptase (Invitrogen). Thymocytes were stained with anti-CD4 (1:400, Clone RM4-5, BD Bioscience), anti-CD8 (1:400, Clone 53-6.7, BioLegend), anti-CD25 (1:200, Clone PC61.5, eBioscience) and anti-CD44 (1:200, Clone IM7, BioLegend) Abs. CD4+ cells, CD8+ cells, DP cells, DN cells and DN cells in different stages were sorted by flow cytometry. T cells and B cells were isolated by magnetic beads (EasySep, Stem Cell Technology, Vancouver, BC, Canada). For RT-qPCR measurement of Armc5 expression during T-cell activation, mouse T-activator CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (ThermoFisher Scientific, Burlington, ON, Canada) were used for T-cell activation in vitro, to avoid introducing Ag-presenting cells into purified CD4 or CD8 cells.

Forward and reverse primers were 5′-CAG TTA TGT GGT GAA GCT GGC GAA-3′ and 5′-ACC CTC AGA AAT CAG CCA CAA CCT-3′, respectively. A 139-bp product was detected with the following amplification program: 95 °C × 15 min, 1 cycle; 95 °C × 10 s, 59 °C × 15 s, 72 °C × 25 s, 35 cycles. β-actin mRNA levels were measured as internal controls. Forward and reverse primers were 5′-TCG TAC CAC AGG CAT TGT GAT GGA-3′ and 5′-TGA TGT CAC GCA CGA TTT CCC TCT-3′, respectively, with the same amplification program as for Armc5 mRNA. The data were expressed as ratios of Armc5 versus β-actin signals.

Armc5 overexpression in L cells

L cells (ATCC CRL-2648, ATCC) were transiently transfected with pReceiver-Lv120 plasmid expressing mouse Armc5 with HA tag (EX-Mm23477-LV120, GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD, USA) for 2 days, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Subcellular Armc5 localization in L cells was detected by immunofluorescence with biotinylated rat anti-HA Ab (1:500, 12158167001, Roche, Laval, QC, Canada), followed by FITC-conjugated streptavidin (1:2,000, S11223, ThermoFisher, Burlington, ON, Canada). The L cells were not authenticated and possible mycoplasma contamination was not tested.

Generation of Armc5 KO mice

A PCR fragment amplified from the Armc5 cDNA sequence served as probe to isolate genomic BAC DNA clone 7O8 from the RPCI-22 129/sv mouse BAC genomic library. The targeting vector was constructed by recombination and routine cloning methods, with a 15-kb Armc5 genomic fragment from clone 7O8 as starting material. A 2.7-kb HindIII/EcoRV genomic fragment containing exon 1–3 was replaced by a 1.1-kb Neo cassette from pMC1Neo-Poly A flanked by two diagnostic restriction sites, EcoRV, and HindIII, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. The final targeting fragment was excised from its cloning vector backbone by NotI/EcoRI digestion and electroporated into R1 embryonic stem (ES) cells for G418 selection. Targeted ES cell clones were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts. Chimeric male mice were mated with C57BL/6 females to establish mutated Armc5 allele germline transmission.

Southern blotting with probes corresponding to 5′ and 3′ sequences outside the targeting region, as illustrated in Fig. 2a (red squares), screened for gene-targeted ES cells and eventually confirmed gene deletion in mouse tail DNA. With the 5′ probe, the targeted allele presented a 6.6-kb EcoRV band, and the WT allele, a 9.3-kb EcoRV band. With the 3′ probe, the targeted allele presented an 8.7-kb HindIII band, and the WT allele, a 12.5-kb HindIII band (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Heterozygous mice were backcrossed to the C57BL/6J background for eight generations and then crossed with 129/sv mice. WT and KO mice in the C57BL/6J × 129/sv F1 background were studied. All animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions and handled in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Protection Committees of the CRCHUM and INRS-IAF.

Serum total IgG measurement

Flat bottom 96-well plates (Costar EIA/RIA, No. 3369, Fisher Scientific) were coated with goat anti-mouse IgG (100 μl per well, 1 μg ml−1 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After five times of washings with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, the plates were blocked with PBS containing 3% BSA and 5% fetal bovine serum for 1.5 h at room temperature. After five washings, diluted serum samples (1:105) and serially diluted standard mouse IgG (sc-2025, Santa Cruz) were added to the wells (100 μl per well) and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The plates were then washed 10 times, and diluted (1:4,000) horse radish peroxidase-conjugated horse anti-mouse IgG (#7076 S, Cell Signaling Technology) was added (100 μl per well) to the wells. The plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After another 10 washings, 1-Step Ultra TMB-ELISA Substrate Solution (#34028, Thermo Scientific) was added to the wells (100 μl per well). The plates were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 20–30 min, and the reaction was stopped by 2 M sulfuric acid (100 μl per well). Optical density at 450 nm of reactants was measured. Samples were assayed in duplicate. Mouse total IgG concentrations were calculated according to a standard curve established by serial dilutions of standard mouse IgG. Assay sensitivity was in the 0.39 and 6.25 ng ml−1 range.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Glucocorticoid levels in WT and KO mouse sera were quantified by ELISA, detecting mouse glucocorticoids according to the manufacturer’s instructions (MBS028416, MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA).

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions from the thymus, spleen and LN were prepared and stained immediately or after culture with Abs against CD3 (1:200, Clone 145-2C11, BD Bioscience), CD4 (1:400, Clone RM4-5, BD Bioscience), CD8 (1:400, Clone 53-6.7, BioLegend), CD25 (1:200, Clone PC61.5, eBioscience), CD44 (1:200, Clone IM7, BioLegend), CD45.1 (1:200, Clone A20, BD Bioscience), CD45.2 (1:200, Clone 104, BD Bioscience), CD62L (1:200, Clone MEL-14, BD Bioscience), CD107a (1:200, Clone 1D4B, BD Bioscience), CD127 (1:200, A019D5, BioLegend), KLRG1 (1:200, Clone 2F1/KLRG1, BioLegend), Thy1.2 (1:1000, Clone 30-H12, BioLegend), B220 (1:200, Clone RA3-6B2, BD Bioscience), 7AAD (1:25, 51-68981E, BD Bioscience), Annexin-V (1:50, 550474, BD Bioscience). In some experiments, intracellular proteins, such as IFN-γ (1:200, Clone XMG1.2, BD Bioscience), IL-17 (1:200, Clone TC11-18H10, BD Bioscience), FoxP3 (1:200, Clone 150D, BioLegend), T-bet (1:200, Clone 4B10, BioLegend), RORγt (1:200, Clone B2D, eBioscience) and TNF-α (1:200, Clone MP6-XT22, BD Bioscience) and Granzyme B (1:200, Clone GB11, BioLegend), were detected after the cells were pre-stained with Abs against cell surface Ag, permeabilized with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences), and then stained with Abs against intracellular Ag38,39.

Flow cytometry was also employed to assess LCMV-specific T cells. The synthetic peptides gp33–41: KAVYNFATC (LCMV-GP, H-2Db), np396–405: FQPQNGQFI (LCMV-NP, H-2Db) and gp276–286: SGVENPGGYCL (LCMV-GP, H-2Db) were purchased from Sigma-Genosys (Oakville, ON, Canada). PE-gp33–41, PE-np396–405 and PE-gp276–286 H-2Db tetrameric complexes were synthesized in-house and applied at 1/100 dilution39. These MHC-tetramers served to detect LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells on day 8 post-LCMV infection. Briefly, splenocytes were first stained with PE-gp33–41, PE-np396–405 or PE-gp276–286 tetramers for 30 min at 37 °C, directly followed by surface staining (CD3, CD8, CD44 and CD62L) and dead cell exclusion (7AAD) for another 20 min at 4 °C. The cells were then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and samples were analysed by flow cytometry.

For intracellular cytokine staining, 106 splenocytes from LCMV-infected mice were maintained for 5 h at 37 °C in RPMI-1640 with 10% FCS and 55 μg ml−1 β-ME, supplemented with a final concentration of 50 U ml−1 IL-2, 5 μg ml−1 Brefeldin A, 2 μM Monensin, 2.5 μg ml−1 FITC-labelled anti-mouse CD107a and 5 μM gp33–41 or gp61–80 GLNGPDIYKGVYQFKSVEFD (LCMV-GP, I-Ab) synthetic peptide from Sigma-Genosys. After ex vivo incubation, surface staining and cell viability were verified with anti-mouse CD8a, CD4 and CD62L mAbs and 7AAD. The cells were then fixed, permeabilized and stained with anti-mouse TNF-α, IFN-γ and Granzyme B mAbs. Cytokine-producing T cells were analysed by flow cytometry40.

Lymphocyte proliferation and apoptosis in vitro

Spleen cells were loaded with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE: 5 μM for 5 min). After washing, they were stimulated with soluble hamster anti-mouse CD3ɛ mAb (clone 145-2C11, 2 μg ml−1; BD Biosciences) for T-cell proliferation assays. This protocol allows best long-term T-cell proliferation over a 4-day period, for clear demonstration of multiple cell proliferation rounds according to CFSE staining. In B-cell proliferation assays, CFSE-loaded Spleen cells were stimulated with goat anti-mouse IgM (5 μg ml−1; Jackson ImmunoResearch), IL-4 (10 ng ml−1) and goat-anti-mouse CD40 (2 μg ml−1, Jackson ImmunoResearch). After 3–4 days, the cells were gated on CD4−, CD8− or B220-positive cells, and their CFSE intensity was ascertained by flow cytometry.

To assess Th1 and Th17 cell proliferation, naive CD4 cells were loaded with CFSE, and cultured under Th1 and Th17 conditions for 4 days (detailed below). CD4+ or intracellular IFN-γ+ or IL-17+ cells were then gated, and their CFSE intensity was assessed by flow cytometry.

For cell cycle analysis, total spleen cells were stimulated with anti-CD3ɛ mAb, as described above, and stained with anti-Thy1.2 mAb and propidium iodide (20 μg ml−1) on days 0, 1 and 2. Thy1.2+ T cells were gated and their propidium iodide signal strength was measured by flow cytometry.

For T-cell apoptosis analysis, spleen cells were stimulated with anti-CD3ɛ mAb (2 μg ml−1) plus crosslinked human FasL-FLAG (0.133 μg ml−1; FasL-FLAG was pre-incubated for 24 h at 4 °C at a 1:1 ratio with 0.133 μg ml−1 mouse monoclonal Ab against FLAG (F1804, Sigma); the final concentration of crosslinked FasL-FLAG for culture was 0.6 μg ml−1 (ref. 41)) and cultured for 4 h. Cells positive for CD4 or CD8 were gated and analysed for annexin V expression.

Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation in vitro

T-cell differentiation in vitro was undertaken as follows38,39. Naive CD4+ T cells (CD4+ CD62L+CD44low) were isolated from KO or WT mouse Spleen with EasySep mouse naive CD4+ T-cell isolation kits (19765, Stem Cell Technology). Naive CD4+ T cells from WT and KO mice (0.1 × 106 cells per well) were mixed with feeder cells (0.5 × 106 cells per well) and cultured in 96-well plates in the presence of soluble anti-CD3ɛ Ab (2 μg ml−1). Feeder cells plus anti CD3ɛ Ab were used, as in our hands, they achieved the most consistent Th1 and Th17 differentiation conditions. Cultures were supplemented with recombinant mouse IL-12 (10 ng ml−1; 419-ML, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and anti-IL-4 mAb (5 μg ml−1; MAB404, R&D Systems) for the Th1 condition, with recombinant mouse IL-6 (20 ng ml−1; 406-ML, R&D Systems), recombinant human TGF-β1 (5 ng ml−1; 240-B, R&D Systems) and anti-IL-4 (5 μg ml−1) and anti-IFN-γ mAbs (5 μg ml−1; MAB485, R&D Systems) for the Th17 condition. The cells were stimulated with PMA (10 μM) and ionomycin (100 μg ml−1) in the presence of 5 μg ml−1 Brefeldin A for the last 4 h of culture, and their intracellular IFN-γ, T-bet, IL-17 and RORγt were analysed by flow cytometry.

Chimera generation

Eight- to 10-week-old C57BL/6J (CD45.2+) × C57B6.SJL (CD45.1+) F1 mice were irradiated at 1,100 rads. Twenty-four hours later, they received i.v. 2 × 106 fetal liver cells from WT or KO mice) in the C57BL/6J × 129/sv (CD45.2+) F1 background. Peripheral white blood cells of recipients were analysed by flow cytometry 8 weeks after fetal liver cell transplantation. Twelve weeks after transplantation, chimeras with successful implantation of donor-derived white blood cells were studied in in vitro T-cell function experiments and for EAE induction.

EAE induction and assessment

EAE was induced in 8- to 12-week-old female WT and KO mice42. Briefly, mice were immunized with 300 μg MOG35–55 peptide (Biomatik, Wilmington, DE, USA) emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant, followed by i.p. injection of 400 ng pertussis toxin (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA, USA) on days 0 and 2. EAE development was scored daily between days 0 and 35 according to a scale ranging from 0 to 5, as follows: 0, no sign of paralysis, 1, weak tail; 2, paralysed tail; 3, paralysed tail and weakness of hind limbs; 4, completely paralysed hind limbs; 5, moribund. Scores were assigned in 0.5 unit increments when symptoms fell between 2 full scores.

Female chimeras with successful donor cell implantation (verified according to CD45.2 single-positive cells in peripheral blood) 12 weeks after fetal liver transplantation were also used for EAE induction. The same protocol described above was followed, except that 200 μg MOG35–55 peptide for immunization and 200 ng pertussis toxin/injection were administered to each chimeric mouse.

EAE histology

To assess the degree of inflammation and CNS demyelination, EAE mice were killed on day 30 and perfused by intra-cardiac injection of PBS. Spinal cord sections were stained with H/E or NovaUltra Luxol Fast Blue Staining Kit (IHC World, Woodstock, MD, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each SC section was subdivided into four regions: 1 anterior, 1 posterior and 2 lateral. Each region was scored on a scale of 0-3 for lymphocyte infiltration and demyelination in a one-way blinded fashion. Thus, each animal had a potentially maximal score of 12 points for lymphocyte infiltration and demyelination, respectively43,44. Total pathological scores were the sum of these 2 parameters.

Isolation of mononuclear cells from the spinal cord and brain

Peripheral blood was removed from the spinal cord and brain by intra-cardiac perfusion through the left ventricle with heparinized ice-cold PBS. The spinal cord and brain were harvested, ground and then passed through a 70-μm mesh screen. The cells were centrifuged through a 40–90% discontinuous Percoll gradient. Mononuclear cells at the 40–60% Percoll interface were collected and stained for phenotype analysis.

Differentiation/characterization of mouse Th1 and Th17 cells

Cells from draining LN and mononuclear cells from the spinal cord and brain were further stimulated with PMA (5 nM) and ionomycin (500 ng ml−1) for 4 h in the presence of Golgi Stop (554724, BD Biosciences), before being harvested. They were stained with Abs against cell surface Ag, fixed with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (555028, BD Biosciences), and then stained with mAbs against intracellular IFN-γ (1:200, Clone XMG1.2, BD Bioscience) and IL-17 (1:200, Clone TC11-18H10, BD Bioscience). Stained cells were analysed by flow cytometry.

LCMV infection

LCMV-WE was obtained from Dr R.M. Zinkernagel (University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland). Viral stock was propagated in vitro, and viral titers were quantified by focus-forming assay40. Mice were infected by the i.v. route with 200 focus-forming units (ffu) of LCMV-WE. They were killed 8 days post-infection, and their spleens were harvested for primary immune response analysis. CD8+ T cells were isolated from the spleen of naive or infected WT mice, with EasySep mouse CD8+ T-cell isolation kits (19853, Stem Cell Technology). RNA from isolated cells was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen), followed by RT-qPCR.

Y2H assay

Y2H screening was performed by Hybrigenics Services (Paris, France). The coding sequence for human ARMC5 cDNA (aa 30–935) (GenBank accession number GI: 157426855) was PCR-amplified and cloned into pB29 as a N-terminal fusion protein to LexA (N-ARMC5-LexA-C). The construct was verified by sequencing the entire insert and served as bait to screen a random-primed human thymocyte cDNA library constructed in the pP6 plasmid. pB29 and pP6 vectors were derived from the original pBTM116 (refs 45, 46) and pGADGH47 plasmids, respectively.

Eighty million yeast clones (eightfold the complexity of the library) were screened via a mating approach with YHGX13 (Y187 ade2-10: loxP-kanMX-loxP, matα) and L40Gal4 (mata) yeast strains48. One hundred sixty-five His+ colonies were selected on medium lacking tryptophan, leucine and histidine, and supplemented with 5.0 mM of 3-aminotriazole to quench bait auto-activation. Prey fragments of positive clones were amplified by PCR and sequenced at their 5′ and 3′ junctions. The resulting sequences were considered to identify corresponding interacting proteins in the GenBank database via a fully automated procedure. A Predicted Biological Confidence score was attributed to each interaction36.

Statistics

For in vivo animal studies, the sample size was determined by estimation, based on our past experience and literature. No formal randomization was used, but littermates or age- and sex-matched WT and KO mice were used. In general, two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used. Chi-square test was used to compare the difference between two proportions. One-way analysis of variance followed with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test was used in data from more than three groups. For the histology experiments, one-way blind examination was performed.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the text and the Supplementary Data files, or from the corresponding author on request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Hu Y, et al. Armc5 deletion causes developmental defects and compromises T-cell immune responses. Nat. Commun. 8, 13834 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13834 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accession codes

References

Nusslein-Volhard, C. & Wieschaus, E. Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature 287, 795–801 (1980).

Wieschaus, E. & Riggleman, R. Autonomous requirements for the segment polarity gene armadillo during Drosophila embryogenesis. Cell 49, 177–184 (1987).

Ozawa, M., Baribault, H. & Kemler, R. The cytoplasmic domain of the cell adhesion molecule uvomorulin associates with three independent proteins structurally related in different species. EMBO J 8, 1711–1717 (1989).

Huber, A. H., Nelson, W. J. & Weis, W. I. Three-dimensional structure of the armadillo repeat region of beta-catenin. Cell 90, 871–882 (1997).

Tewari, R., Bailes, E., Bunting, K. A. & Coates, J. C. Armadillo-repeat protein functions: questions for little creatures. Trends Cell. Biol. 20, 470–481 (2010).

Hatzfeld, M. The armadillo family of structural proteins. Int. Rev. Cytol. 186, 179–224 (1999).

Conti, E., Uy, M., Leighton, L., Blobel, G. & Kuriyan, J. Crystallographic analysis of the recognition of a nuclear localization signal by the nuclear import factor karyopherin alpha. Cell 94, 193–204 (1998).

Hatzfeld, M., Haffner, C., Schulze, K. & Vinzens, U. The function of plakophilin 1 in desmosome assembly and actin filament organization. J. Cell Biol. 149, 209–222 (2000).

Keil, R. & Hatzfeld, M. The armadillo protein p0071 is involved in Rab11-dependent recycling. J. Cell Sci. 127, 60–71 (2014).

Roberts, D. M., Pronobis, M. I., Poulton, J. S., Kane, E. G. & Peifer, M. Regulation of Wnt signaling by the tumor suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli does not require the ability to enter the nucleus or a particular cytoplasmic localization. Mol. biol. cell 23, 2041–2056 (2012).

Zhao, G., Li, G., Schindelin, H. & Lennarz, W. J. An armadillo motif in Ufd3 interacts with Cdc48 and is involved in ubiquitin homeostasis and protein degradation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 16197–16202 (2009).

Pipino, C. et al. Calcium sensing receptor activation by calcimimetic R-568 in human amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cells: correlation with osteogenic differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 23, 2959–2971 (2014).

Tan, F., Qian, C., Tang, K., Abd-Allah, S. M. & Jing, N. Inhibition of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) signaling can substitute for Oct4 protein in reprogramming and maintain pluripotency. J. biol. chem. 290, 4500–4511 (2015).

Hillesheim, A., Nordhoff, C., Boergeling, Y., Ludwig, S. & Wixler, V. beta-catenin promotes the type I IFN synthesis and the IFN-dependent signaling response but is suppressed by influenza A virus-induced RIG-I/NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Commun. Signal. 12, 29 (2014).

Liu, C. C., Pearson, C. & Bu, G. Cooperative folding and ligand-binding properties of LRP6 beta-propeller domains. J. biol. chem. 284, 15299–15307 (2009).

Bujalowski, P. J., Nicholls, P., Barral, J. M. & Oberhauser, A. F. Thermally-induced structural changes in an armadillo repeat protein suggest a novel thermosensor mechanism in a molecular chaperone. FEBS lett. 589, 123–130 (2015).

Xie, C. et al. ARMC8alpha promotes proliferation and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer cells by activating the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Tumour Biol. 35, 8903–8911 (2014).

Riese, J. et al. LEF-1, a nuclear factor coordinating signaling inputs from wingless and decapentaplegic. Cell 88, 777–787 (1997).

Iguchi, H. et al. SOX6 suppresses cyclin D1 promoter activity by interacting with beta-catenin and histone deacetylase 1, and its down-regulation induces pancreatic beta-cell proliferation. J. biol. chem. 282, 19052–19061 (2007).

Kim, S. et al. Wnt and CDK-1 regulate cortical release of WRM-1/beta-catenin to control cell division orientation in early Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E918–E927 (2013).

Xu, Y., Banerjee, D., Huelsken, J., Birchmeier, W. & Sen, J. M. Deletion of beta-catenin impairs T cell development. Nat. Immunol. 4, 1177–1182 (2003).

Mucenski, M. L. et al. beta-catenin is required for specification of proximal/distal cell fate during lung morphogenesis. J. biol. chem. 278, 40231–40238 (2003).

Soshnikova, N. et al. Genetic interaction between Wnt/beta-catenin and BMP receptor signaling during formation of the AER and the dorsal-ventral axis in the limb. Genes Dev. 17, 1963–1968 (2003).

Zhao, T. et al. beta-catenin regulates Pax3 and Cdx2 for caudal neural tube closure and elongation. Development 141, 148–157 (2014).

Dao, D. Y. et al. Cartilage-specific beta-catenin signaling regulates chondrocyte maturation, generation of ossification centers, and perichondrial bone formation during skeletal development. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 1680–1694 (2012).

Guo, X. et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is sufficient and necessary for synovial joint formation. Genes Dev. 18, 2404–2417 (2004).

Kim, A. C. et al. Targeted disruption of beta-catenin in Sf1-expressing cells impairs development and maintenance of the adrenal cortex. Development 135, 2593–2602 (2008).

Simcha, I., Geiger, B., Yehuda-Levenberg, S., Salomon, D. & Ben-Ze'ev, A. Suppression of tumorigenicity by plakoglobin: an augmenting effect of N-cadherin. J. Cell Biol. 133, 199–209 (1996).

National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. ARMC5 armadillo repeat containing 5 [Homo sapiens (human)]—Gene—NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/79798 (October 31, 2016).

National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Armc5 armadillo repeat containing 5 [Mus musculus (house mouse)]—Gene—NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/233912 (October 31, 2016).

Bardwell, V. J. & Treisman, R. The POZ domain: a conserved protein-protein interaction motif. Genes Dev. 8, 1664–1677 (1994).

Ahmad, K. F., Engel, C. K. & Prive, G. G. Crystal structure of the BTB domain from PLZF. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12123–12128 (1998).

Zollman, S., Godt, D., Prive, G. G., Couderc, J. L. & Laski, F. A. The BTB domain, found primarily in zinc finger proteins, defines an evolutionarily conserved family that includes several developmentally regulated genes in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10717–10721 (1994).

Assie, G. et al. ARMC5 mutations in macronodular adrenal hyperplasia with Cushing's syndrome. N. Engl. j. med. 369, 2105–2114 (2013).

Sarkar, S. et al. Functional and genomic profiling of effector CD8 T cell subsets with distinct memory fates. J. exp. med. 205, 625–640 (2008).

Formstecher, E. et al. Protein interaction mapping: a Drosophila case study. Genome res. 15, 376–384 (2005).

Marcinkiewicz, M. BetaAPP and furin mRNA concentrates in immature senile plaques in the brain of Alzheimer patients. J. neuropathol. exp. neurol. 61, 815–829 (2002).

Luo, H. et al. Efnb1 and Efnb2 proteins regulate thymocyte development, peripheral T cell differentiation, and antiviral immune responses and are essential for interleukin-6 (IL-6) signaling. J. biol. chem. 286, 41135–41152 (2011).

Terra, R. et al. To investigate the necessity of STRA6 upregulation in T cells during T cell immune responses. PLoS ONE 8, e82808 (2013).

Lacasse, P., Denis, J., Lapointe, R., Leclerc, D. & Lamarre, A. Novel plant virus-based vaccine induces protective cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-mediated antiviral immunity through dendritic cell maturation. J. virol. 82, 785–794 (2008).

Han, B., Moore, P. A., Wu, J. & Luo, H. Overexpression of human decoy receptor 3 in mice results in a systemic lupus erythematosus-like syndrome. Arthritis rheum. 56, 3748–3758 (2007).

Luo, H., Yu, G., Tremblay, J. & Wu, J. EphB6-null mutation results in compromised T cell function. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 1762–1773 (2004).

Bright, J. J., Du, C., Coon, M., Sriram, S. & Klaus, S. J. Prevention of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis via inhibition of IL-12 signaling and IL-12-mediated Th1 differentiation: an effect of the novel anti-inflammatory drug lisofylline. J. immunol. 161, 7015–7022 (1998).

Butterfield, R. J. et al. Identification of genetic loci controlling the characteristics and severity of brain and spinal cord lesions in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Am. j. pathol. 157, 637–645 (2000).

Vojtek, A. B. & Hollenberg, S. M. Ras-Raf interaction: two-hybrid analysis. Methods enzymol. 255, 331–342 (1995).

Beranger, F., Aresta, S., de Gunzburg, J. & Camonis, J. Getting more from the two-hybrid system: N-terminal fusions to LexA are efficient and sensitive baits for two-hybrid studies. Nucleic acids res. 25, 2035–2036 (1997).

Bartel, P., Chien, C.-T., Sternglanz, R. & Fields, S. Cellular interactions in development: a practical approach (ed. Hartley, D.) 153–179Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK (1993).

Fromont-Racine, M., Rain, J. C. & Legrain, P. Toward a functional analysis of the yeast genome through exhaustive two-hybrid screens. Nat. genet. 16, 277–282 (1997).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to J.W. (MOP69089 and MOP 123389), A.L. (MOP89797) and H.L. (MOP97829). It was also funded by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (203906-2012), the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (17-2013-440), Fonds de recherche du Quebéc-Santé (Ag-06) to J.W., and the Jean-Louis Levesque Foundation to J.W and A.L. The authors thank Dr M. Sarfati and her group for sorting thymocytes by flow cytometry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H., L.L., J.M., A.L. and J.W. conceived and designed the experiments. Y.H., L.L., J.M., W.J., H.L., T.C., S.Q., J.P. and M.M.M. performed the experiments. Y.H., L.L., J.M., W.J., H.L., T.C., M.M.M., B.H. and J.W. analysed the data. Y.H., L.L., A.L. and J.W. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary figures 1-15 and supplementary table 1. (PDF 1754 kb)

Supplementary Dataset 1

Results summary of Y2H screen. (PDF 1087 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Lao, L., Mao, J. et al. Armc5 deletion causes developmental defects and compromises T-cell immune responses. Nat Commun 8, 13834 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13834

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13834

This article is cited by

-

ARMC5 controls the degradation of most Pol II subunits, and ARMC5 mutation increases neural tube defect risks in mice and humans

Genome Biology (2024)

-

Primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia: definitely a genetic disease

Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2022)

-

A novel nonsense mutation in ARMC5 causes primary bilateral macronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia

BMC Medical Genomics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.