Abstract

Extremely metal-poor galaxies with metallicity below 10% of the solar value in the local universe are the best analogues to investigating the interstellar medium at a quasi-primitive environment in the early universe. In spite of the ongoing formation of stars in these galaxies, the presence of molecular gas (which is known to provide the material reservoir for star formation in galaxies such as our Milky Way) remains unclear. Here we report the detection of carbon monoxide (CO), the primary tracer of molecular gas, in a galaxy with 7% solar metallicity, with additional detections in two galaxies at higher metallicities. Such detections offer direct evidence for the existence of molecular gas in these galaxies that contain few metals. Using archived infrared data, it is shown that the molecular gas mass per CO luminosity at extremely low metallicity is approximately one-thousand times the Milky Way value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Galaxies in the early universe contained few metals (elements heavier than helium) and dust grains1. On the surface of dust grains, hydrogen atoms combined efficiently into hydrogen molecules2, which served as the fuel of star formation in present-day spiral galaxies, including our own Milky Way galaxy3. The lack of metals thus poses a question regarding the presence of molecular gas in the primordial galaxies through, for example, the gas-phase reaction4. The extremely metal-poor galaxies in the local universe, with the oxygen abundance relative to hydrogen <10% of the solar value, provide the best local insights into understanding the interstellar medium in a quasi-primitive environment. Although there is an indirect evidence for the presence of molecular gas in these galaxies5,6,7, the emission from the molecule carbon monoxide (CO), which is the primary tracer of molecular gas, has never been detected in them8,9,10,11,12,13.

In this study, we report the detection of CO in a galaxy at 7% of solar metallicity, along with additional detections in galaxies at 13% and 18% solar metallicity; these data offer direct evidence for the existence of molecular gas in these metal-poor galaxies. By comparing this data to the gas mass as traced by dust emission, the molecular gas mass per CO luminosity in these galaxies is found to be much higher than that of the Milky Way galaxy.

Results

Observations

The galaxy DDO 70 is an extremely metal-poor galaxy at a distance of 1.38 Mpc (ref. 14), with the gas-phase oxygen abundance relative to hydrogen 12+log(O/H)=7.53 (ref. 15), compared with the solar abundance at 12+log(O/H)=8.66 (ref. 16). We have observed two additional dwarf galaxies at somewhat higher metallicity, including DDO 53 and DDO 50 at 3.68 Mpc (ref. 14) and 3.27 Mpc (ref. 14), respectively, with 12+log(O/H)=7.82 (ref. 17) and 7.92 (ref. 17), respectively. As shown in Fig. 1, we targeted four dusty star-forming regions in these three galaxies as listed in Table 1, using the Institut de Radioastronomie Millimetrique (IRAM) 30-m telescope. For each star-forming region, we pointed the telescope to the far-infrared peak that traces gas density enhancement with ongoing star formation. No prior CO detections of these regions have been reported, possibly because previous works targeted the peak of atomic gas often with a short exposure time10.

(a) The image of DDO 70, where red denotes infrared emission at 160 μm, green denotes the far-UV emission and blue denotes the atomic hydrogen 21 cm emission. (b) The image of DDO 53. (c) The image of DDO 50. All the white scale bars are 40″ across. (d) The CO J=2−1 spectra for region A in DDO 70. (e) The CO J=2−1 spectra for region A in DDO 53. (f) The CO J=2−1 spectra for region A in DDO 50. (g) The CO J=2−1 spectra for region B in DDO 50. The spectral channel width is 0.5, 1.0, 4.0 and 1.0 km s−1 for DDO70-A, DDO53-A, DDO50-A and DDO50-B, respectively, and the corresponding 1−σ continuum sensitivity is 3.94, 4.17, 3.13 and 4.89 mK, respectively.

CO emission

We detected CO J=2−1 emission in all four star-forming regions, including one in DDO 70 at 7% (labelled as DDO70-A), one in DDO 53 at 14% (labelled as DDO53-A) and two in DDO 50 at 18% (labelled as DDO50-A and DDO50-B) solar metallicity. The spectra and results are shown in Fig. 1 and listed in Table 1. The 1−σ continuum sensitivity is 3.94, 4.17, 3.13 and 4.89 mK for DDO70-A, DDO53-A, DDO50-A and DDO50-B, respectively, at a spectral resolution of 0.5, 1.0, 4.0 and 1.0 km s−1, respectively. The CO J=2−1 of DDO70-A has a S/N of 5.5 with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 2.4 km s−1, and the CO J=2−1 of DDO53-A is detected at a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of 7.1 with a FWHM of 7 km s−1. The CO line of DDO50-A has an integrated S/N of 5.9 with a FWHM of 18 km s−1. The emission of DDO50-B appears to have two velocity components. A single Gaussian fitting gives a value of S/N of 6.1 for the integrated strength peaked at the velocity of 163 km s−1 with an FWHM of 10 km s−1, and two Gaussian fittings give S/Ns of 6.1 and 3.2 for the two components at 161 and 167 km s−1, respectively, with FWHMs of 3.2 and 3.4 km s−1, respectively. The CO J=1−0 transition was covered by our observation but was not detected. The 3−σ lower limits to the ratios CO(J=2−1)/CO(J=1−0) in the main-beam temperature are 1.9, 0.9, 1.5 and 0.9 for DDO70-A, DDO53-A, DDO50-A and DDO50-B, respectively. As the size of a CO-emitting region shrinks significantly at the low metallicity11, we assumed point sources for CO-emitting regions relative to our IRAM beam (∼100–200 pc). The above ratio is thus still consistent with the assumption that the CO emission is thermalized and optically thick.

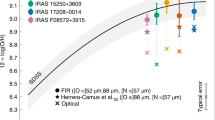

Figure 2 shows the total infrared luminosity (8–1,000 μm) versus the CO luminosity as well as the star-formation rate (SFR) versus the CO luminosity of these metal-poor star-forming regions. Here the CO luminosity defined for J=1−0 is obtained with  (J=1−0)=

(J=1−0)= (J=2−1) by assuming optically thick and thermalized CO emission. Both the infrared luminosity and SFR are measured after convolution to match the beam of the IRAM 30 m at the CO J=2−1 frequency. For comparison, massive star-forming galaxies of approximately solar metallicity3,18 are also included in the figure. As is well known, the CO luminosity is related to both far-infrared luminosities and SFRs among massive star-forming galaxies, indicating that the molecular gas mass as traced by CO is related to star-formation activities. At a low metallicity, CO decreases because of not only the eliminated reservoir of carbon and oxygen elements but also the increased dissociation of CO molecules by ultraviolet photons under the condition of low dust extinction. As indicated in the figure, both infrared/CO and SFR/CO ratios at a low metallicity are significantly higher than those of massive galaxies. In massive galaxies, infrared luminosity is a good tracer of the SFR, accounting for only a part of the SFR because of the low dust content in metal-poor galaxies. As a result, the increase in the SFR/CO ratio from massive galaxies to metal-poor ones is greater than that in the infrared/CO ratio.

(J=2−1) by assuming optically thick and thermalized CO emission. Both the infrared luminosity and SFR are measured after convolution to match the beam of the IRAM 30 m at the CO J=2−1 frequency. For comparison, massive star-forming galaxies of approximately solar metallicity3,18 are also included in the figure. As is well known, the CO luminosity is related to both far-infrared luminosities and SFRs among massive star-forming galaxies, indicating that the molecular gas mass as traced by CO is related to star-formation activities. At a low metallicity, CO decreases because of not only the eliminated reservoir of carbon and oxygen elements but also the increased dissociation of CO molecules by ultraviolet photons under the condition of low dust extinction. As indicated in the figure, both infrared/CO and SFR/CO ratios at a low metallicity are significantly higher than those of massive galaxies. In massive galaxies, infrared luminosity is a good tracer of the SFR, accounting for only a part of the SFR because of the low dust content in metal-poor galaxies. As a result, the increase in the SFR/CO ratio from massive galaxies to metal-poor ones is greater than that in the infrared/CO ratio.

(a) The infrared luminosity versus CO luminosity of our metal-poor star-forming regions compared with massive star-forming galaxies. The error bar is the s.d., which is basically the photon noise for each measurement of luminosity. (b) The SFR versus CO luminosity of our metal-poor star-forming regions as compared with massive star-forming galaxies. The error bar is the s.d. The error of the CO luminosity is the photon noise, and the error of the SFR is the photon noise plus systematic uncertainty. The red diamonds denote our observed four regions, and the blue circles denote massive star-forming galaxies3. The solid line is the best fit to star-forming disk galaxies18, whereas the dashed line is the best fit to the star-forming starburst galaxies18.

Discussion

The detection of CO in these objects indicates that molecular gas is present at a very low metallicity. This presence implies that CO can still be a tracer of molecular gas at a very low metallicity. To constrain the conversion factor from the CO luminosity to the molecular gas mass, we estimated the gas mass through the dust emission. All our galaxies have multiband infrared images available in the archive of the Herschel Space Observatory and HI gas maps as observed by Very Large Array19. We constructed the infrared spectral energy distribution (SED) of each region covered by the IRAM 30-m beam (11″) and fitted it with a dust model20 to derive the dust mass (see Methods section). We used the gas-to-dust ratio of an extremely metal-poor galaxy (Sextans A, 7% solar metallicity)7 by assuming the gas-to-dust ratio equal to 8,000(Z/0.07)−1.0, where Z is the metallicity. Here the function of the gas-to-dust ratio with the metallicity is suggested by some observations21. Note that we used the same dust model set-up as that for Sextans A to derive the dust mass, thus eliminating the uncertainty caused by the variation of the dust grain properties. After subtracting the atomic gas, the molecular gas mass is obtained. The derived molecular gas has a relatively large uncertainty that results from the photometric error in the infrared SED, the uncertainty in the dust modelling, the HI gas mass error and the error of the gas-to-dust ratio (see Methods section for details).

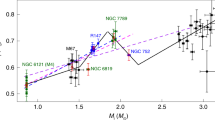

Figure 3 shows the conversion factor of our metal-poor star-forming regions along with those in the literatures22,23,24,25, where the molecular gas content is derived through the spatially resolved dust and HI gas map. Although previous works are limited to the metallicity 12+log(O/H)>8.0, our study indicates that the conversion factor increases rapidly below this metallicity limit. The extremely metal-poor galaxy DDO 70 has a conversion factor about three orders of magnitude higher than the value of the Milky Way galaxy. Another three star-forming regions at 10–20% solar metallicity have conversion factors between ∼100 and 500. One difference in our study compared with those at higher metallicity is that we only targeted the intense star-formation peaks. In these regions, the strong radiation field may increase the effects of CO dissociation, thus biasing the conversion factor towards large values. However, these regions are also infrared peaks with more abundant dust with respective to the rest of the galaxy; such dust may protect CO from dissociation.

The four red diamonds denote the result of our metal-poor star-forming regions, and all other symbols denote those observations in the literature9,22,23,24. The error bars of our measurements are the s.d., which are caused by the uncertainties on the CO luminosity, the HI gas mass and the dust mass as well as the dust-to-gas ratio. The lines denote models’ predictions, including the empirical one24 as well as theoretical ones26,27,28,29. The parameters in those models were set basically following the literature work8, including a linear scaling of the dust-to-gas ratio with the metallicity, and a typical gas surface density of 100  pc−2 in the Milky Way.

pc−2 in the Milky Way.

In spite of the large uncertainties, the derived conversion factors are still useful to differentiate different theoretical models that give a very large range of predictions at a low metallicity as illustrated in Fig. 3. The empirical relationship (solid yellow line)24 based on data above 12+log(O/H)=8.0 is a steep function, and its extrapolations at our metallicity are consistent with our observations. Among all theoretical models, the one that invokes photodissociation of CO and H2 self-shielding26 matches the observations including ours at a very low metallicity. Other models either overpredict or significantly underpredict the data at the low metallicity end27,28,29.

Methods

Observation details

We carried out the CO J=2−1 observation using the IRAM 30 m during 22–29 March 2016 (programme ID: 168–15, PI: Y. Shi) with a total of 59.5 h granted. The Eight Mixer Receiver with dual polarization and the Fourier Transform Spectrometers backend were used. To have a good baseline for the spectrum, we adopted the standard wobbler switching mode at a 0.5-Hz beam throwing with an offset of ±120″. The pointing and focussing were set at the beginning of each run and then re-calibrated every 2 h by pointing to the bright quasars close to our targets. The data reduction was performed with CLASS in the GILDAS package. For each region, we averaged all scans to obtain the final one. The effective on-source integration time including two polarization as indicated by CLASS is 1210, 413, 369 and 556 min for DDO70-A, DDO53-A, DDO50-A and DDO 50-B, respectively, with system temperatures of 252, 223, 382 and 283 K, respectively.

Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the CO spectra over a velocity range of ±150 km s−1 to illustrate the goodness of a long baseline for our observations. The HI spectrum within each IRAM beam is also extracted from the HI data cube19 and overlaid on the CO spectrum as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The CO line is within the HI velocity range, although there are some offsets in the central velocity between the two that further validates the reliability of our CO detections.

Infrared spectral energy distributions

The infrared images from 70 to 250 μm as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 were retrieved from the archive of the Herschel Space Observatory. The spatial resolutions are about 6″, 12″ and 18″ at 70, 160 and 250 μm, respectively. The data were reduced using the unimap30. The standard procedure of the reduction includes the time ordering of the pixels, signal preprocessing, glitch removal, drift removal, making the noise spectrum and generalized least square (GLS) filter, map making with GLS, postprocessing of the GLS map and finally the weighted postprocessing of the GLS map. The mid-infrared images at 3.6, 4.5, 5.8, 8.0 and 24 μm were retrieved from the archive of the Spitzer Space Telescope that is available through the Local Volume Legacy program31 with the corresponding spatial resolutions of 1.6″, 1.7″, 1.9″, 2.0″ and 6″, respectively.

To estimate the dust mass, we constructed the infrared SED based on the Spitzer and Herschel images. We first checked the astrometry using field stars and corrected the offsets between the two telescopes, about 1 arcsec for DDO 70 and DDO 53 and 7 arcsec for DDO 50. As the IRAM beam size (11″) is relatively small given the spatial resolutions at those IR wavelengths, the aperture correction is important. We used three approaches to derive the infrared SED. The first approach is to assume point sources for the aperture corrections at all infrared wavelengths and then measure the flux within the IRAM beam for each band at native spatial resolutions. This approach gives the largest possible aperture corrections, which could be treated as upperlimits, given that the star-forming regions are spatially resolved at Spitzer 24 μm and Herschel 70 μm. The following two methods assume that the star-forming regions are extended sources at Spitzer 24 μm and Herschel 70 μm to correct the flux loss for Herschel 160 and 250 μm. For the second approach, we convolved all infrared images above 24 μm to the SPIRE 250 μm using the convolution Kernels32 and then measured the flux within the IRAM beam. These fluxes are then corrected for the aperture loss by multiplying with the ratio of the flux of Spitzer 24 μm at its native resolution to that at the convolved resolution. The third method is the same as the second one but convolves the 24 μm, 70 and 160-μm images to Gaussian 11″ beams excluding the 250-μm image, and again, this approach corrects the flux loss with the ratio of the 24-μm flux at the native resolution to that at the convolved resolution. The derived photometric results using three approaches were found to be within 50%. For our discussion, we have adopted the second approach, which adopts images convolved to the Herschel 250 μm resolution and aperture corrections based on the Spitzer 24 μm image, given that the star-forming regions are spatially resolved at 24 μm. As we pointed at the bright infrared peaks, the photon noise is small while the photometric error is instead dominated by the aperture correction because of the small IRAM beam. We assigned 50% of fluxes as systematic uncertainties for the infrared photometry at all wavelengths. The final SED is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Measurements of the physical properties

Following our previous work7, the infrared SED is fitted with a dust model20 to obtain the dust mass measurement. We adopted the Milky Way dust grains and fixed the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon fraction to be the minimum given the low metallicity of our galaxies. The maximum intensity of the stellar radiation field is further fixed to be 106. Thus the model has three free parameters, including the dust mass, the minimum stellar light intensity and the fraction of dust exposed to the minimum radiation field. An additional 4,000 K black body is included to model the emission from the stellar photosphere. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3 and listed in Supplementary Table 1, the fitting results are reasonably good. If using the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) dust model, the dust mass differs by no more than 15%, which is consistent with previous studies7,33.

To derive the total gas mass from the dust mass, the gas-to-dust ratio is needed. Unlike our previous work7, the infrared observation is not deep enough to derive the gas-to-dust ratio based on the diffuse light for individual galaxies. We thus adopted the gas-to-dust ratio (8,000) of Sextans A at 7% solar from the previous work7 that is based on the diffuse light as the value for DDO 70, which is at the same metallicity. Given the large variation in the gas-to-dust ratio from object to object21 at this metallicity, we assigned 0.5 dex as 1−σ uncertainty of the ratio. For DDO 50 and DDO 53, we assumed a linear increase of the gas-to-dust ratio with the decreasing metallicity following the literature study21, with a 1−σ uncertainty of ∼0.3 dex at their metallicities. As discussed in the previous work7, although different dust grain models provide different dust masses, these different dust masses do not affect the derived gas masses because the dust-to-gas ratio changes accordingly.

To obtain the molecular gas, the atomic gas mass is subtracted from the dust-based total gas mass. The HI gas maps of three galaxies were observed with the Very Large Array through the program of Local Irregulars That Trace Luminosity Extremes19. We adopted the robust-weighted maps with the synthesized beam sizes of 13.8″ × 13.2″, 6.3″ × 5.7″ and 7.0″ × 6.1″ for DDO 70, DDO 53 and DDO 50, respectively. Although the DDO 70 has a resolution that is slightly worse than that of our IRAM beam, the HI emission is pretty diffuse so that we can assume the HI mass surface density measured at its resolution is a good approximation of that within the IRAM beam. For DDO 53 and DDO 50, we convolved the HI maps to the 11″ beam to measure the HI mass, which is almost the same (<10%) as those measured at the native resolution, given the HI emission is diffuse. We also retrieved the reduced far-ultraviolet images from the GALEX data archive (http://galex.stsci.edu/GalexView/) whose spatial resolution is about 5″. The SFR is the combination34 of the unobscured part (as traced by far-ultraviolet) and the obscured part (as traced by 24-μm emission). The SFRs of massive galaxies used for comparison in Fig. 2 are based on their infrared luminosities3 using the formula35 with corrections for Chabier initial mass function (IMF). The stellar mass is derived based on the 3.6 and 4.5-μm emission36.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Shi, Y. et al. Carbon monoxide in an extremely metal-poor galaxy. Nat. Commun. 7, 13789 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13789 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Walter, F. et al. Evidence for low extinction in actively star-forming galaxies at z>6.5. Astrophys. J. 752, 93–98 (2012).

Wolfire, M. G. et al. Chemical rates on small grains and PAHs: C+ recombination and H2 formation. Astrophys. J. 680, 384–397 (2008).

Gao, Y. & Solomon, P. M. HCN survey of normal spiral, infrared-luminous, and ultraluminous galaxies. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 152, 63–80 (2004).

Abel, T. et al. Modeling primordial gas in numerical cosmology. New Astron. Rev. 2, 181–207 (1997).

Madden, S. C. et al. [C II] 158 micron observations of IC 10: evidence for hidden molecular hydrogen in irregular galaxies. Astrophys. J. 483, 200–209 (1997).

Hunt, L. et al. The Spitzer view of low-metallicity star formation. III. Fine-structure lines, aromatic features, and molecules. Astrophys. J. 712, 164–187 (2010).

Shi, Y. et al. Inefficient star formation in extremely metal poor galaxies. Nature 514, 335–338 (2014).

Bolatto, A. et al. The CO-to-H2 conversion factor. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 51, 207–268 (2013).

Elmegreen, B. G. et al. Carbon monoxide in clouds at low metallicity in the dwarf irregular galaxy WLM. Nature 495, 487–489 (2013).

Warren, S. R. et al. CARMA CO observations of three extremely metal-poor, star-forming galaxies. Astrophys. J. 814, 30–38 (2015).

Rubio, M. et al. Dense cloud cores revealed by CO in the low metallicity dwarf galaxy WLM. Nature 525, 218–221 (2015).

Hunt, L. K. et al. Molecular depletion times and the CO-to-H2 conversion factor in metal-poor galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 583, A114 (2015).

Amorn, R. et al. Molecular gas in low-metallicity starburst galaxies: scaling relations and the CO-to-H2 conversion factor. Astron. Astrophys. 588, A23 (2016).

Tully, R. B. et al. Cosmicflows-2: the data. Astron. J. 146, 86–110 (2013).

Kniazev, A. Y. et al. Spectrophotometry of Sextans A and B: chemical abundances of H II regions and planetary nebulae. Astron. J. 130, 1558–1573 (2005).

Asplund, M. et al. The chemical composition of the Sun. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 47, 481–522 (2009).

Croxall, K. V. et al. Chemical abundances of seven irregular and three tidal dwarf galaxies in the M81 group. Astrophys. J. 705, 723–738 (2009).

Genzel, R. et al. A study of the gas-star formation relation over cosmic time. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2010, 2091–2108 (2010).

Hunter, D. A. et al. Little things. Astron. J. 144, 134–162 (2012).

Draine, B. T. et al. Infrared emission from interstellar dust. IV. The silicate-graphite-PAH model in the post-Spitzer era. Astrophys. J. 657, 810–837 (2007).

Rémy-Ruyer, A. et al. Gas-to-dust mass ratios in local galaxies over a 2 dex metallicity range. Astron. Astrophys. 2014, A31 (2014).

Sandstrom, K. M. et al. The CO-to-H2 conversion factor and dust-to-gas ratio on kiloparsec scales in nearby galaxies. Astrophys. J. 777, 5–37 (2013).

Leroy, A. K. et al. The CO-to-H2 conversion factor from infrared dust emission across the local group. Astrophys. J. 737, 12–24 (2011).

Israel, F. P. H2 and its relation to CO in the LMC and other magellanic irregular galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 328, 471–482 (1997).

Shi, Y. et al. The weak carbon monoxide emission in an extremely metal-poor galaxy, Sextans. Astrophys. J. Lett. 804, 11–14 (2015).

Glover, S. C. O. & Mac Low, M.-M. On the relationship between molecular hydrogen and carbon monoxide abundances in molecular clouds. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 412, 337–350 (2011).

Narayanan, D. et al. A general model for the CO-H2 conversion factor in galaxies with applications to the star formation law. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 3127–3146 (2012).

Wolfire, M. G. et al. The dark molecular gas. Astrophys. J. 716, 1191–1207 (2010).

Feldmann, R., Gnedin, N. Y. & Kravtsov, A. V. The X-factor in galaxies. I. Dependence on environment and scale. Astrophys. J. 747, 124–144 (2012).

Traficante, A. et al. Data reduction pipeline for the Hi-GAL survey. Maris 416, 2932–2943 (2011).

Dale, D. A. et al. The Spitzer local volume legacy: survey description and infrared photometry. Astrophys. J. 703, 517–556 (2009).

Aniano, G. et al. Common-resolution convolution kernels for space- and ground-based telescopes. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 123, 1218–1236 (2011).

Draine, B. et al. Dust masses, PAH abundances, and starlight intensities in the SINGS galaxy sample. Astrophys. J. 663, 866–894 (2007b).

Leroy, A. K. et al. The star formation efficiency in nearby galaxies: measuring where gas forms stars effectively. Astron. J. 136, 2782–2845 (2012).

Kennicutt, R. Star formation in galaxies along the Hubble sequence. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 36, 189–232 (1998).

Eskew, M., Zaritsky, D. & Meidt, S. Converting from 3.6 and 4.5 μm fluxes to stellar mass. Astron. J. 143, 139–145 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This study is based on observations carried out under project number 168-15 with the IRAM 30-m telescope. IRAM is supported by INSU/CNRS (France), MPG (Germany) and IGN (Spain). Y.S. acknowledges support for this work from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC grant 11373021), the Strategic Priority Research Program The Emergence of Cosmological Structures of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. XDB09000000) and the Excellent Youth Foundation of the Jiangsu Scientific Committee (grant BK20150014). J.W. is supported by the National 973 program (grant 2012CB821805) and by the NSFC (grant 11590783). Z.-Y.Z. acknowledges support from the European Research Council in the form of the Advanced Investigator Programme, 321302, COSMICISM. Y.G. is supported by Pilot-b (XDB09000000) and NSFC (grant 11390373 and 11420101002). C.-N.H. and X.-Y.X. acknowledge the support from the NSFC grant 11373027. Q.G. was supported by the NSFC (11273015 and 11133001) and by the National 973 programme (grant 2013CB834905).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. led the IRAM proposal and the writing of the manuscript. Y.S. and J.W. performed the observations and reduced the data. All others helped develop the proposal and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-3 and Supplementary Table 1 (PDF 266 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Y., Wang, J., Zhang, ZY. et al. Carbon monoxide in an extremely metal-poor galaxy. Nat Commun 7, 13789 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13789

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13789

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.