Abstract

The energy-level alignment of molecular transistors can be controlled by external gating to move molecular orbitals with respect to the Fermi levels of the source and drain electrodes. Two-terminal molecular tunnelling junctions, however, lack a gate electrode and suffer from Fermi-level pinning, making it difficult to control the energy-level alignment of the system. Here we report an enhancement of 2 orders of magnitude of the tunnelling current in a two-terminal junction via chemical molecular orbital control, changing chemically the molecular component between a stable radical and its non-radical form without altering the supramolecular structure of the junction. Our findings demonstrate that the energy-level alignment in self-assembled monolayer-based junctions can be regulated by purely chemical modifications, which seems an attractive alternative to control the electrical properties of two-terminal junctions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The possibility to integrate functional molecules into electronic devices is one of the promising approaches to miniaturize electronic circuits or to generate electronic function that is difficult to obtain using conventional semiconductors1,2,3. The advantage of molecular-based devices is, in principle, that the conductance can be tuned by designing molecules with the electronic and chemical structure tailored for the desired application. To achieve this ‘chemical control’ over transport characteristics, a good control over the energy-level alignment of the molecular frontier orbitals with respect to the Fermi level (EF) of the electrodes is needed. For instance, control over the energy-level alignment has been used in thin film devices to lower charge injection barriers by either altering the work function of the metal-electrodes4, or controlling the HOMO (highest-occupied molecular orbital) and/or LUMO (lowest unoccupied molecular orbital) levels with respect to the Fermi levels by chemical modification5,6, or introducing charge injection layers7,8. In practical systems, however, chemical control over the energy-level alignment proves to be challenging because of the so-called ‘pillow effect’ or Fermi-level pinning7. In molecular electronics, especially in the case of two-terminal devices, it remains difficult to predict how, if at all, certain chemical functionalities alter the junction characteristics9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Here we show how the tunnelling rates across molecular junctions can be increased by 2 orders of magnitude by tuning the energy levels of the system within the conduction window without the need for altering the molecular structure of the molecule–electrode interfaces by modifying the electronic structure of the molecules between the open- and closed-shell forms. Since the nature of the molecule–electrode interface is kept the same for both molecular forms, this approach is not limited by Fermi-level pinning.

The molecule bridging the two electrodes provides the molecular energy levels (E) in the solid-state device for conduction channels. The sum of the channels (M(E)) within the electrochemical potential window between μL and μR, will result in an effective current, as described by the Landauer formalism16,17,18:

where h is Planck’s constant, q is the electron charge and T(E) is the transmission probability, which is inversely proportional to the square of zero-bias energy off-set between the molecular orbital and the Fermi level of the electrodes (δEME), equation (2),

where ΓL and ΓR are the degree of the coupling strength between the molecular frontier orbital and the Fermi level of the left (L) and the right (R) electrodes, respectively. Thus, the current (I) is proportional to the M(E) and inversely proportional to (δEME) (ref. 2). Although in three-terminal devices the energy-level alignment of the systems, that is, the value of δEME, can be controlled via a gate electrode (or in a wet electrochemical environment gating via the electrolyte is possible)19,20,21,22, in two-terminal devices, however, the molecular orbitals cannot be gated and therefore alternative approaches are needed.

One of these approaches is to control the energy-level alignment of the system by modifying the chemical structure of the molecules inside the junctions. In reality, it is difficult to predict how changes to the chemical structure of the junctions affect the electrical properties of the junctions and seemingly contradicting results have been reported. In SAM-based junctions, the difficulty of controlling the energy-level alignment due to Fermi-level pinning has been well-recognized.7,23 For example, Frisbie and co-workers24 showed that changing the work function of the metal had a noticeable effect on the contact resistance (due to a large surface dipole at the metal–thiolate interface) but not on the energy-level alignment. Similarly, Blom and co-workers25 found that introducing additional dipoles in the SAM structure results in large work function shifts. In contrast, Whitesides and co-workers13,14,15 observed that the tunnelling rates across aliphatic SAMs in EGaIn junctions were independent of dipoles or acidity of small end groups of alkanethiolate SAMs. We confirmed these findings by Whitesides and co-workers15 for a small subset of SAM structures, but Whitesides and co-workers and we also showed that other functionalities, such ferrocene (Fc) and redox-active aromatic groups26,27,28, or polarizable groups (halogens)29, did change the junction characteristics and induced rectification or changed the tunnelling rates, respectively. These studies show, as a group, that it is indeed difficult to predict which kind of chemical functionalities result in a noticeable change in the electrical characteristics of the junctions. One of the reasons is that changes in the molecular structure also result in changes of the molecule–electrode interactions and the supramolecular structure of the SAM making it difficult to isolate the factors that dominate the charge transport rates.

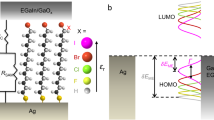

In this study, the charge transport rate across SAM-based tunnelling junctions with the same electrode–molecule interfaces and supramolecular structure but with different electronic structure modified by chemically switching the molecule between the open- and closed-shell forms is investigated. In particular, we incorporate SAMs of polychlorotriphenylmethyl radical (PTMR) and of non-radical polychlorotriphenylmethane (PTMNR) molecules tethered to the Au bottom electrode via an alkanethiolate linker into EGaIn junctions. The open-shell form contains a SOMO (single occupied molecular orbital), with one electron with an α spin configuration, and a SUMO (single unoccupied molecular orbital), and this results in a smaller molecular energy SOMO–SUMO gap than the HOMO–LUMO gap of the closed-shell form (ΔE values in Fig. 1). Similar observations have been made in an organic thin film in a wet electrochemical environment25. Thus, we change the electronic structure of the PTM while keeping the PTM—electrode interactions the same as the PTM is separated from the top-electrode via a van der Waals interface and the bottom-electrode via the alkyl group. Moreover, we show that not only the energy gap is lowered but also the value of δEME (or in other words, the energy-level alignment changed) which results in a low tunnelling barrier height and thereby a high-tunnelling current.

Schematic representations of the junctions of AuTS-SC10PTMR/NR//GaOxcond/EGaIn and the corresponding energy level diagrams. The top-electrodes (a) are liquid metal GaOxcond/EGaIn (where EGaIn is the eutectic alloy of Ga and In, and GaOxcond is a 0.7-nm-thick self-limiting highly conductive oxide layer)15,16,17. The bottom electrodes (b) are template-stripped Au surfaces (∼300-nm-thick, see fabrication methods in ref. 11 and Methods for details). The ΔE and δEME represent the molecular energy gap and zero-bias energy off-set between the LUMO (or SUMO) and the Fermi level of the electrodes, respectively. Red dots show the central C atoms of radical moieties. The distance (d) between two electrodes is about 2.1 nm.

We investigated the mechanism of charge transport through a SAM of a free organic radical based on PTM radical because it is stable and can be readily grafted on gold30,31, glass32 and ITO33, or as a single molecule linked between gold electrodes showing a Kondo effect at low temperatures34. The PTM radical has one unpaired electron located on the central carbon atom with a sp2 hybridization, which is structurally shielded by the bulky o-chlorine atoms, leading to a high chemical and thermal stability35. This radical can be readily converted to the alpha-H non-radical derivative via reduction to the anion and protonation of the central carbon. Previously, the charge transport rates across PTMR/NR SAMs on gold were investigated by conductive probe atomic force microscopy (cpAFM), showing a higher tunnelling rate across junctions with PTMR-based SAMs than those junctions with PTMNR-based SAMs36,37. Theoretical calculations of the electronic structure of the gas phase molecules suggested SUMO-assisted transport in the case of the radical-based SAM. Based on these calculations, it was assumed that the mechanism of charge transport was coherent tunnelling without direct experimental evidence regarding the electronic structure of the junction- or temperature-dependent charge transport data. This assumption, however, may have been not correct because in these studies the PTM moiety was grafted to the bottom-electrode via a short-conjugated tether. Likely significant hybridization of the molecular frontier orbital with the gold electrode occurs and resonant transport cannot be excluded.

Here we demonstrate that the mechanism of charge transport is coherent tunnelling in both types of PTMR/NR SAMs bearing long (6 or more CH2 units) non-conjugated alkyl tether, to ensure the molecular frontier orbitals remain localized on the PTM and that tunnelling rates across the junction can be increased by 2 orders of magnitude in the open-shell based SAMs with respect to the closed-shell ones without changing the tunnelling distance d or the nature of the molecule–electrode contacts. This increase in the tunnelling rates is because in junctions with the PTMR SAMs, the SUMO participates in the transport and effectively lowers the tunnelling barrier height (see Fig. 1). Importantly, contrary to what we hypothesized in previous works36,37, the findings reported here unambiguously demonstrate that the enhancement of the tunnelling rate transport across the radical-based SAMs is not due to a resonant tunnelling mechanism but instead due to a SUMO-assisted coherent non-resonant tunnelling. We base our conclusions on statistically large numbers of J(V) data and J(V,T) measurements combined with a detailed physical-organic study of the electronic and supramolecular SAM structures using six newly designed PTM derivatives with different chain lengths. All SAMs are anchored on gold via a thiolate binding group and the PTMR/NR moieties are effectively decoupled from the electrode via the long alkyl chains. Hence, all types of SAMs yield similar work functions of gold. Here we show intramolecular control over the electronic structure of the junction, resulting in a large change in the value of δEME and, consequently, the observed tunnelling rates. In other words, we show a large modulation of the tunnelling rate of 2 orders of magnitude across junctions with the same supramolecular structure and work function of the electrodes.

Results

Molecular synthesis

Three PTM-CH=CH-(CH2)n−2SH radicals and three αH-PTM-CH=CH-(CH2)n−2SH non-radicals, with n=8, 10 and 12, have been synthesized. We use the abbreviations HSCnPTMR/NR for simplicity to follow the discussions. Figure 2 shows the synthetic route to the PTM-thiolated derivatives HSCnPTMR/NR. We aimed to couple the alkyl chain with the thiol-anchoring group to the PTM unit using a C=C bond, because the double bond only causes a small modification to the electronic structure of the PTM (unlike electron donating/withdrawing groups such as amides or carbonyls) and it can be readily formed by a Wittig–Horner reaction between the PTM-phosphonate and an aldehyde bearing the corresponding alkyl chain and the thiol-precursor38. To overcome the instability of the thiol groups under the Wittig–Horner conditions, as well as under the oxidative conditions needed to generate the radical from the corresponding carbanion, we used a triphenylmethyl (trityl) as a protecting group. This protecting group was easily deprotected in acidic media in the last step of the synthesis to obtain the final thiolated compounds (Fig. 2). High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) confirmed that, despite the reducing character of the thiol groups and the low-reduction potential of the PTM radicals21, PTM-thiolated derivatives are stable for several weeks in ambient conditions. We note that storing for extended periods of time disulfide derivatives formed as a result of the oxidation of the thiol groups. The same was observed for the non-radical counterparts and, for this reason, all SAMs reported here were prepared using freshly deprotected thiolate derivatives.

SAM structural characterization

The SAMs were prepared using freshly template-stripped Au surfaces with ultra-flat topography39,40,41, which were immersed in 0.5 mM solutions of the target compound in toluene. Before the fabrication of the top-electrode, the SAMs were characterized by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and angle-resolved X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (ARXPS) to ensure that we used good-quality SAMs (See Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Figs 13–16 for the complete data sets). The ARXPS and element ratios (see more details in Method section ‘Photoelectron spectroscopy’ and ‘Determination of the thickness of the SAMs from the S 2p spectra’) analysis from XPS revealed that both radical and non-radical SAMs are in a standing-up phase rather than lying flat on the surface, the calculated layer thickness (d) scales with n and was similar for PTMNR and PTMR SAMs with the same number of n, and that all SAMs had very similar surface coverage (1.4–1.6 × 10−9 mol cm−2) within experimental error (5%) (see Supplementary Table 1 and Methods). From our results, we conclude that the supramolecular structure of the SAM does not change when the PTM units are in the open- or closed-shell forms.

SAM electronic structure characterization

The electronic structure of the SAMs on AuTS was determined by ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) and near edge X-ray adsorption fine structure spectroscopy (NEXAFS) to estimate the positions of the filled and empty states, respectively. The UPS spectra were recorded to determine their energy levels with respect to the Fermi level of a clean Au substrate for all PTMR/NR-AuTS SAMs. Figure 3a shows the UPS spectra of the HSCnPTMR SAMs. We found that the SOMO peak with a SOMO-onset value of ∼1.45 eV is clearly visible in contrast to the spectra obtained from HSCnPTMNR SAM that do not show this peak (here only HSC12PTMNR SAM is shown as representative of the PTMNR SAMs; see Supplementary Fig. 17 for n=8 and 10) and only reveal the HOMO peak with the HOMO-onset value at ∼2.45 eV. This is a clear evidence of the persistence of the unpaired electron once the molecules are covalently grafted on the surface.

The C K-edge NEXAFS spectra (Fig. 3b) show peaks at ∼285.7 and ∼286.5 eV, which are assigned to the C(Ph)→π* transitions in the perchlorinated phenyl rings of the PTM molecules42. These peaks are present in the spectra of PTMR and PTMNR SAMs, but in the case of the PTMR SAMs there is an additional peak at ∼282.9 eV. This peak indicates the presence of an empty state with an energy just above the Fermi level and it is attributed to the transition to the SUMO orbital42,43. We have calculated the SUMO (for the PTMR SAMs) and LUMO (for the PTMNR SAMs) energy position from the NEXAFS spectra (Table 1, see details in Methods). Thus, the molecular energy gap of the PTMR/NR SAMs could be calculated from UPS and NEXAFS spectra (Table 1) and the results are comparable with the optical band gap (∼1.9 eV for R and ∼3.9 eV for NR) determined by the ultraviolet–visible spectra (see Supplementary Figs 6 and 7).

We note that the energy levels determined by these techniques only involve SAMs. We believe that the energy levels shift once the SAMs form a contact with the GaOxcond/EGaIn top-electrodes, though we believe these shifts are small due to the non-covalent nature of the SAM//GaOxcond/EGaIn contact. Thus, the energy levels depicted in Fig. 1 give a good qualitative indication of the energy levels. Moreover these experimental data indicate that the SUMOs of radical and LUMOs of non-radical SAMs, are closer to the EF of GaOx/EGaIn (−4.2 eV)44 and SAM-modified AuTS bottom electrodes (−4.1 to −4.2 eV) than the SOMO and HOMO. Therefore we believe the mechanism of charge transport involves tunnelling via the SUMO or LUMO orbitals. We note that the nature of the charge carrier cannot be directly measured in these two-terminal devices, but our results agree with the findings reported by Cahen and co-workers45 for n-alkanethiolate SAMs that showed that transport is dominated by the unoccupied molecular orbitals.

Transport through the SAMs

For this study, we used liquid metal GaOxcond/EGaIn top-electrodes since they form non-invasive soft top-contacts with the SAMs11,46,47. To fabricate the molecular junctions, the HSCnPTMR/NR derivatives were first self-assembled on ultra-smooth AuTS bottom electrodes and followed by the formation of the top-electrodes following previously reported methods (see Methods)48,49. The AuTS-SCnPTMR/NR//GaOxcond/EGaIn junctions were measured under the same experimental conditions and we biased the top-electrodes and grounded the bottom electrodes. We collected at least 21 traces on 20 different junctions for each type of junctions (see Table 1 for all statistics). The data were plotted in histograms of log10|J| at each applied bias (voltage steps of 0.05 V), and then we fitted Gaussians to the histograms to obtain the mean values of log10|J| (

To investigate the charge transport mechanism in more detail, we carried out temperature-dependent charge transport measurements in the range of temperatures (T) from 340 to 210 K. We used a device made of a polymeric transparent polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mold having micro-channels that stabilize the GaOxcond/EGaIn (see ref. 51 and Methods for details). The GaOxcond/EGaIn formed contact with the SAM through small round-orifices present in the polymeric mold. These devices generate stable junctions over at least 1,000 traces (see Supplementary Fig. 12) and allow us to perform temperature-dependent measurements in the probestation. Figure 5a shows averaged J(V) curves from 10 J(V) traces at each temperature for the three radical SAM-based junctions, and Fig. 5b shows the Arrhenius plots for J at −1.0 V (see Supplementary Fig. 18 and Methods for temperature-dependent J(V) measurements of non-radical SAM-based junctions, that is, NRs). For the whole measured temperature range, the measured values of J (A cm−2) for the three radical SAMs are all temperature independent, which indicate the charge transport mechanism is in tunnelling regime.

To investigate the dependence of J as a function of tunnelling distance (d), here we used carbon number n as the equivalent for d and plotted

where β is the tunnelling decay coefficient (in n−1) and J0 (A cm−2) is a constant including the contact resistance and it measures the current density flowing through the electrode-SAM interface in the hypothetical case of zero separation between the electrodes52. The values of β only show a small difference for both types of junctions (βR=0.89±0.01 n−1 and a βNR=1.03±0.03 n−1) but the values of J0 differ strongly in the magnitude (logJ0,R=3.0±0.2 and logJ0,NR=1.9±1.2). Here, the error bar represents the 95% confidence level from least absolute deviation (LAD) fitting (see procedure of LAD fitting in ref. 26). These β values are similar in value to those reported for insulating organic molecules (n-alkanethiols), which have β values between 0.9 and 1.1 n−1 (refs 28, 39, 53). The magnitudes of the values of J0 are in line with other SAM-based molecular junctions but at least 1,000 times lower than single molecular junctions due to the differences in effective contact area between the techniques47,54. It was reported before that the values of β are proportional to the square root of the δEME for coherent non-resonance tunnelling through a rectangular barrier, that is,  (refs 55, 56). The δEME values of PTMNR SAMs are consistently ∼2 times higher than PTMR SAMs, which leads to about a 1.4 times increase in β. This back of the envelope calculation is in line with our measured data that the βNR at −1.0 V is about 1.2 times higher than βR (this estimation does not take into account the shape of the barrier and the renormalization of the energy levels when bias is applied). This result also suggests that the decay rate is dominated by the length of the alkyl chain and the PTM moiety is effectively decoupled from the Au electrode by the long alkyl tether. This observation is supported by temperature-dependent measurements, which demonstrate that for over the entire measured temperature range, the values of J are independent of the temperature for the PTMR junctions. Along with the exponential decay of J with d, we believe that the mechanism of charge transport is direct tunnelling53,57. This interpretation also agrees with equation (2) and the large difference in J0,R and J0,NR values relates to the difference in δEME values: the radical SAM-based junctions have smaller δEME values and thus larger higher transmission probabilities (T) than the non-radical analogues.

(refs 55, 56). The δEME values of PTMNR SAMs are consistently ∼2 times higher than PTMR SAMs, which leads to about a 1.4 times increase in β. This back of the envelope calculation is in line with our measured data that the βNR at −1.0 V is about 1.2 times higher than βR (this estimation does not take into account the shape of the barrier and the renormalization of the energy levels when bias is applied). This result also suggests that the decay rate is dominated by the length of the alkyl chain and the PTM moiety is effectively decoupled from the Au electrode by the long alkyl tether. This observation is supported by temperature-dependent measurements, which demonstrate that for over the entire measured temperature range, the values of J are independent of the temperature for the PTMR junctions. Along with the exponential decay of J with d, we believe that the mechanism of charge transport is direct tunnelling53,57. This interpretation also agrees with equation (2) and the large difference in J0,R and J0,NR values relates to the difference in δEME values: the radical SAM-based junctions have smaller δEME values and thus larger higher transmission probabilities (T) than the non-radical analogues.

In previous reports some of us claimed that resonant tunnelling is important where the SOMO energy determines the tunnelling barrier height. These assumptions were based on electronic structure calculations using molecules in the gas phase without accounting for Fermi-level pinning as a result of the metal–thiolate bond. The energy level diagram shown in Fig. 1 is based on experimental data (Table 1) from which we conclude that the empty levels define the tunnelling barrier height and not the filled levels. Although the exact shape of the tunnelling barrier inside the junctions during charge transport is not known, we believe that the energy-level diagram represents our system well considering the non-covalent nature of SAM//top contact. Although the junctions are asymmetric and the empty levels of the PTMR moieties are energetically and spatially very close to the Fermi level of the top-electrode and separated from the bottom electrode by the alkyl, we do not observe significant current rectification. In contrast, similar junctions but with Fc or bipyridyl (BIPY) end groups do rectify26,58. These diodes rectify currents because hopping (thermally activated charge transport) involving the Fc or BIPY is important. However, redox-active SAMs with p-quinone end groups resulted in rectifying EGaIn junctions with low rectification ratios of 3.5 (ref. 28). Although molecular asymmetry is needed to obtain rectification, the magnitude of rectification depends on many factors including the shape of the electrostatic potential profile48, the terminal group coupling with the EGaIn top electrode48,58 or relaxation time of the charge carrier on the molecule (or activation energy for hopping)16,59. Currently, we do not know why certain end groups facilitate hopping while others do not.

Discussion

In summary, a family of PTM radical (which have single-occupied molecular orbitals), and the corresponding non-radical (which have filled molecular orbitals), derivatives of different molecular lengths bearing a thiol group has been synthesized and successfully integrated in molecular junctions of the type of AuTS-SCnPTMR/NR/GaOxcond/EGaIn. Temperature- and chain length-dependent measurements indicate that the mechanism of charge transport across all the junctions is direct tunnelling. This work exemplifies that stable free organic radicals are interesting systems, in addition to others, in molecular junctions because they have small SOMO/SUMO or HOMO/LUMO gaps. In addition, the possibility of having the radical and non-radical junctions make it possible to re-align the molecular energy levels with respect to the Fermi-levels of the metal contacts without altering the nature of the molecule—metal contacts or the backbone of the molecule and, thus, avoiding issues such as Fermi-level pinning.

Our results demonstrate that intramolecular control over the energy-level alignment of molecular tunnelling junctions is a promising approach to control the electrical characteristics of two-terminal molecular junctions. We believe that in the future our findings may be extended to other types of junctions or to control, or perhaps induce, new electronic function.

Methods

Synthesis

The general procedure of the synthesis of PTM derivatives is outlined in Supplementary Fig. 1. The detailed synthesis and characterization of PTM derivatives are described in the Supplementary Methods. The representative infrared (IR), cyclic voltammetry (CV), ultraviolet–visible and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of radicals are shown in Supplementary Figs 2–9.

Fabrication of template-stripped bottom-electrode

We have reported before the procedure for template stripping using epoxy (EpoTek 353ND)44,49,60. Briefly, we deposited A 200-nm-thick Au (with a purity of 99.999% both from Super Conductor Materials Inc) film on clean Si(100) wafers by thermal deposition (Shen Yang Ke Yi, China). The evaporation rate was about 0.3 Å s−1 for the first 50 nm and then increased to ∼5 Å s−1 to deposit the remaining 150 nm and the deposition vacuum was about 2 × 10−6 mbar. We cut the glass slides into pieces of 1 × 0.5 cm2 and then cleaned them in a solution of H2SO4:H2O2=1:5 (in volume) at 80 °C for 20 min, and then washed with H2O to pH 7 and drying in a stream of N2 gas. The glass slides were further cleaned by a plasma of air for 5 min at a pressure of 5 mbar. We dropped the epoxy on the Au surfaces and carefully added the glass slides on top of the epoxy. After the whole wafer was covered with glass slides, we cured the epoxy at 80 °C for 8 h in an oven (Epec). The final step was to lift off the glass slides with Au surfaces glued on them before immersion in the thiol solutions to minimize contamination of the AuTS surfaces by air.

Formation of the SAMs

AuTS surfaces were immersed in a freshly prepared solution of 0.5 mM of each compound in toluene (HPLC grade) for 24 h at 40 °C and then for an additional 24 h at room temperature. Always, before immersing the substrates, the solution was degassed with argon. During the SAM formation, the solution was kept in dark and under argon atmosphere to avoid the decomposition of the radical species. After the time indicated above, the substrates were removed from the solution and were washed with toluene and dichloromethane to remove any physisorbed materials. The modified substrates were characterized immediately after removal from the solution. The electrochemical characterization was performed using 300 nm Au evaporated on mica from Georg Albert (Germany). Before their use, the substrates were rinsed with acetone, dichloromethane and ethanol and then exposed to ozone for 20 min. Immediately after that the substrates were immersed in ethanol (HPLC grade) for at least 30 min. Before immersing the substrates in the PTM derivative solution, they were rinsed with ethanol and dried under nitrogen stream.

Electrochemical characterization of the SAMs

The three SAMs of Au-SCnPTM were electrochemically characterized by using CV performed with an AUTOLAB 204 with NOVA 1.9 software. We used a custom built electrochemical cell with a Pt-wire as counter electrode, Ag-wire as pseudo reference electrode and the modified Au(111) on mica as working electrode. The area exposed to the tetrabutylamonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6) in dichloromethane electrolyte solution (0.1 M) was 0.26 cm2. The CVs were recorded in the range +0.1 V to −0.6 V. The electrochemical measurements were performed in a Faraday cage. CV depicted in Supplementary Fig. 10 shows the CV of the R10 SAM as representative for the different SAMs.

Fabrication of PDMS top-electrodes

We have reported the fabrication of the top-electrodes of Ga2O3/EGaIn stabilized in PDMS in detail elsewhere51. Since the fabrication methods are essentially the same, we only provide Supplementary Fig. 11, which shows the microscope image of the through-hole filled with Ga2O3/EGaIn. A small gap of roughly 10 μm is present between the Ga2O3/EGaIn and the wall of the PDMS. In all the measurements reported here, we used electrodes with a geometrical contact area of about 7.1 × 102 μm.

Fabrication of AuTS-SCnPTMR/NR//GaOxcond/EGaIn junctions

The fabrication of the SAM-based junctions with cone-shaped tips of GaOxcond/EGaIn were reported previously11. Briefly, in our experiments we grounded the bottom electrode with a gold probe penetrating the SAMs and the top-electrode of GaOxcond/EGaIn was biased from 0 V→1.0 V→0 V→−1.0 V→0 V, with a step size of 50 mV and a delay of 0.1 s, to record the J(V) curves. The statistical analysis follows previous reported methods11 and the results are listed in Table 1.

Stability measurement of AuTS-SC8PTMR/NR//GaOxcond/EGaIn junctions

To investigate whether the junctions are stable and do not change during voltage cycling, we prepared junctions with the PDMS top-electrodes described in Methods section `Fabrication of PDMS top-electrodes' and measured 1,000 J(V) traces in the bias range of ±1.0 V. All the J(V) traces for both types of junctions (that is, with SAMs of R8 (red) and NR8 (black)) are plotted in Supplementary Fig. 12. The shape of the J(V) traces did not change significantly and the values of J remained constant over 1,000 traces (plotted in Supplementary Fig. 12B for +1.0 V).

Photoelectron spectroscopy

We have reported the measurement procedures and analysis of synchrotron-based photoemission spectroscopy (PES) measurements (XPS and UPS) and NEXAFS spectroscopy at the SINS (Surface, Interface and Nanostructure Science) beamline of the Singapore Synchrotron Light Source (SSLS) elsewhere54. Briefly, the base pressure was kept at 1 × 10−10 mbar. We used the Au 4f7/2 core level peak at 84.0 eV measured from a sputter-cleaned gold foil in electrical contact with the sample to calibrate the photon energy. We chose 350 eV for the Cl 2p, S 2p and C 1s for the XPS measurements, and 60 eV for the valence band measurements. To measure the work function, we applied –10 V bias to the sample to overcome the work function of the analyser. All UPS spectra were referenced to the Fermi edge of Au and all PES spectra were normalized by the photon current. For NEXAFS, we measured the photon energy from 270 eV to 330 eV. Two take-off angles (90° and 40°) were used to probe the angle-dependence. We performed the least-square peak fit analysis with Voigt functions (Lorentzian (30%) and Gaussian (70%)) using XPSpeak software, and the sloping background was modelled using Shirley plus linear background correction61,62. Supplementary Figs 13–16 show the high-resolution PES spectra with fits of Cl 2p, C 1s and S 2p of the SAMs of AuTS-SCnPTMR/NR at two different take-off angles 90° and 40°, respectively. Supplementary Fig. 17 shows the UPS and NEXAFS spectra of AuTS-SCnPTMNR (n=8 and 10).

The C 1s high-resolution spectra show three components: (1) C–C single bond at ∼284.2 eV labelled C1, (2) the central C (αC) of the PTM moiety and the C=C group at ∼285.2 to ∼285.3 eV labelled C2, and (3) aromatic C–Cl at ∼286.4 eV labelled C3 (ref. 62). The Cl 2p spectra show typical doublet peaks. The doublet peak of the S 2p spectra are solely (or mainly) contributed by the typical S–Au bond at the binding energy of 161.8 eV. The SAMs of R8 and NR8 show a small portion of low binding energy at ∼160.8 eV, which has been reported before and is assigned to chemical absorption of the SAMs at grain boundaries62. We summarized the fitting results of the XPS spectra of C 1s and Cl 2p in the form of the elemental ratio in Supplementary Table 2. From Supplementary Table 2, we can make three conclusions: (1) the decrease of C1/C3 ratios from carbon number 8 to 12 indicate the SAMs are standing up; (2) the C2/C3 ratios are constant at 90° emission but slightly decrease at 40° due to the attenuation of the first C connected to the PTM group and (3) the Cl/C3 ratios are constant for different SAMs and the difference between 90° and 40° emission angle is caused by the large attention of the central C signal compared with the Cl atom.

Determination of the surface coverage of the SAMs from the S 2p spectra

To calculate the surface coverage of the PTMR/NR SAMs, we determined the integrated intensity of Cl 2p spectra (ICl) of the PTMR/NR and S(CH2)10CH2Cl (SC11Cl) SAMs (listed in the Supplementary Table 1). Since the Cl atoms were connected to the terminal groups of the SAMs, the ICl can be related to the surface coverage of the SAMs. The relative surface coverage was calculated by comparing the ICl of the PTMR/NR SAMs, which divided by 14 (PTMR/NR SAMs contains 14 Cl atoms), against that of SC11Cl SAMs. The surface coverage of SC11Cl SAMs on Ag has been reported before and is 1.1 × 10−9 mol cm−2 (ref. 29). Thus, we compared the values of ICl of the PTMR/NR SAMs against those of the SC11Cl SAMs to calculate the relative surface coverage of the PTMR/NR SAMs (Supplementary Table 1). We estimated the uncertainties to be about 5% from the fitting errors of Cl 2p spectra. However, we note that not all of the 14 Cl atoms on the PTM moiety are located at the top of the SAMs, and the signal of at least 4 Cl atoms (connected to the phenyl ring with alkyl chain) are attenuated by half of the length (∼6.3 Å) of the PTM moiety. Thus, the surface coverage calculated by XPS here was underestimated by at least 13% (= ). Nevertheless, the relative surface coverages are the same for all the PTM SAMs which support our conclusion that we did not change the supramolecular structure of the PTMR/NR SAMs.

). Nevertheless, the relative surface coverages are the same for all the PTM SAMs which support our conclusion that we did not change the supramolecular structure of the PTMR/NR SAMs.

We also estimated the theoretical surface coverage of these SAMs formed on the Au(111) surface, and the dimension of the PTM moiety was calculated from CPK model. Since the PTM moiety is a planer-triangle, its projection on the x–y plane changes between rectangles (or a parallelogram dependent on the molecular tilt angle which we do not know). We estimated a surface coverage of 1.8 × 10−10 mol cm−2 from the simple case of rectangle projection (side lengths: a=12.6 Å and b=7.4 Å). The surface coverage estimated from XPS is similar to the theoretical estimation.

Determination of the thickness of the SAMs from the S 2p spectra

We have reported the methods to fit the spectra and to calculate the SAM thickness from angle-dependent XPS measurements in ref. 48. We only give a short description here. The SAM thickness (d, nm) can be expressed as the sum of the Au–S bond (dAu–S=1.8 Å)63 and the over layer thickness (the distance from the middle of the S atom to vacuum) d2 in equation (4)

The different angles of the incident light (γ) result in different emission area on the samples. To normalize the footprint of incident light, we calculate the effective intensity (Iθ)

where I is the integrated intensity of the peak. The values of Iθ are exponentially dependent on d2 and on the take-off angle

where the d1 (=1.5 Å) is estimated from the radius of S atoms and the S–C bond, and λ (=8 Å) is the inelastic mean free path62. We can rewrite the equation (6) to calculate the value of d2

The S 2p spectra along with fits are shown in Supplementary Figs 12–15, and the results are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The uncertainty of ±2 Å takes into account the fitting errors and the angular misalignment due to sample mounting.

Calculation of LUMO energy level from NEXAFS spectra

We determined the SUMO or LUMO level with respect to the Fermi level of the electrode by the binding energy of the C 1s core level of the PTM from the XPS spectra (Supplementary Figs 13–18) and the SUMO or LUMO peak from the NEXAFS spectra with a correction of 0.5 eV for core–hole exciton-binding energy to take into account the core–hole attraction effect. Others have reported correction factors in the range of 0.1–2.0 eV (ref. 64), but we have used 0.5 eV also for other types of SAMs as described in the supporting information of ref. 60. Since we used for both types of junctions with NR and R SAMs the same correction factor, the energy levels for both types of junctions would shift equally in case one would chose different correction factors and hence will not affect our conclusions.

Temperature-dependent measurement of a junction with a SAM of NR8

We used EGaIn top-electrodes stabilized in a through-hole in PDMS to form stable junctions, and measured the temperature-dependent J(V) in a probe station as mentioned in the main text. Supplementary Fig. 18 shows the J(V) traces recorded at 250–330 K at intervals of 10 K. Both the Arrhenius plots and the J(V) traces show that the junction characteristics are independent of temperature as expected, since the non-radical SAMs have larger molecular energy gaps than their radical counterparts and behave as tunnelling barrier.

LAD fitting

As mentioned in the manuscript, we performed LAD fitting of the tunnelling equation (equation (3) in the main text) to the full data set of log10|J| at different applied bias (V) from −1.0 V to −0.1 V. The details of the LAD fitting have been reported in ref. 65. Supplementary Fig. 19 shows the plot of the tunnelling decay coefficient (β) against V. We found that the value of β of the junctions with SAMs of PTMNR is consistently ∼1.2 times higher than that of PTMR.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yuan, L. et al. Chemical control over the energy-level alignment in a two-terminal junction. Nat. Commun. 7:12066 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12066 (2016).

References

Akkerman, H. B. & de Boer, B. Electrical conduction through single molecules and self-assembled monolayers. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 013001 (2008).

Aviram, A. & Ratner, M. Molecular rectifiers. Chem. Phys. Lett. 29, 277–283 (1974).

Cui, X. D. et al. Making electrical contacts to molecular monolayers. Nanotechnology 13, 5–14 (2002).

Heimel, G., Romaner, L., Zojer, E. & Bredas, J.-L. The interface energetics of self-assembled monolayers on metals. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 721–729 (2008).

Malen, J. A. et al. Identifying the length dependence of orbital alignment and contact coupling in molecular heterojunctions. Nano Lett. 9, 1164–1169 (2009).

Coughlin, J. E., Henson, Z. B., Welch, G. C. & Bazan, G. C. Design and synthesis of molecular donors for solution-processed high-efficiency organic solar cells. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 257–270 (2014).

Hung, L. S. & Chen, C. H. Recent progress of molecular organic electroluminescent materials and devices. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 39, 143–222 (2002).

Scott, J. C. Metal-organic interface and charge injection in organic electronic devices. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 21, 521–531 (2003).

Mativetsky, J. M. et al. Azobenzenes as light-controlled molecular electronic switches in nanoscale metal-molecule-metal junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 9192–9193 (2008).

Liu, Y. et al. Giant enhancement in vertical conductivity of stacked CVD graphene sheets by self-assembled molecular layers. Nat. Commun. 5, 5461 (2014).

Nerngchamnong, N. et al. The role of van der Waals forces in the performance of molecular diodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 113–118 (2013).

Sayed, S. Y., Fereiro, J. A., Yan, H., McCreery, R. L. & Bergren, A. J. Charge transport in molecular electronic junctions: Compression of the molecular tunnel barrier in the strong coupling regime. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11498–11503 (2012).

Yoon, H. J., Bowers, C. M., Baghbanzadeh, M. & Whitesides, G. M. The rate of charge tunnelling is insensitive to polar terminal groups in self-assembled monolayers in AgTSS(CH2)nM(CH2)mT//Ga2O3/EGaIn Junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16–19 (2014).

Liao, K.-C., Yoon, H. J., Bowers, C. M., Simeone, F. C. & Whitesides, G. M. Replacing AgTSSCH2-R with AgTSO2C-R in EGaIn-based tunnelling junctions does not significantly change rates of charge transport. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 3889–3893 (2014).

Yoon, H. J. et al. The rate of charge tunnelling through self-assembled monolayers is insensitive to many functional group substitutions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 4658–4661 (2012).

Joachim, C. & Ratner, M. A. Molecular electronics: some views on transport junctions and beyond. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 8801–8808 (2005).

Landauer, R. Spatial variation of currents and fields due to localized scatterers in metallic conduction (and comment). J. Math. Phys. 37, 5259–5268 (1996).

Datta, S. Lessons from Nanoelectronics: A New Perspective on Transport Vol. 1, World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. (2012).

Díez-Pérez, I. et al. Rectification and stability of a single molecular diode with controlled orientation. Nat. Chem. 1, 635–641 (2009).

Frisenda, R. et al. Kondo effect in a neutral and stable all organic radical single molecule break junction. Nano Lett. 15, 3109–3114 (2015).

Fave, C. et al. Tunable electrochemical switches based on ultrathin organic films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 1890–1891 (2007).

Capozzi, B. et al. Tunable charge transport in single-molecule junctions via electrolytic gating. Nano Lett. 14, 1400–1404 (2014).

Lenfant, S. et al. Electron transport through rectifying self-assembled monolayer diodes on silicon: Fermi-level pinning at the molecule−metal interface. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 13947–13958 (2006).

Kim, B., Choi, S. H., Zhu, X. Y. & Frisbie, C. D. Molecular tunnel junctions based on pi-conjugated oligoacene thiols and dithiols between Ag, Au, and Pt contacts: Effect of surface linking group and metal work function. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19864–19877 (2011).

de Boer, B., Hadipour, A., Mandoc, M. M., van Woudenbergh, T. & Blom, P. W. M. Tuning of metal work functions with self-assembled monolayers. Adv. Mater. 17, 621–625 (2005).

Yuan, L., Thompson, D., Cao, L., Nerngchamnong, N. & Nijhuis, C. A. One carbon matters: The origin and reversal of odd–even effects in molecular diodes with self-assembled monolayers of ferrocenyl-alkanethiolates. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 17910–17919 (2015).

Nijhuis, C. A., Reus, W. F. & Whitesides, G. M. Molecular rectification in metal-SAM-metal oxide-metal junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 17814–17827 (2009).

Reus, W. F., Thuo, M. M., Shapiro, N. D., Nijhuis, C. A. & Whitesides, G. M. The SAM, Not the electrodes, dominates charge transport in metal-monolayer//Ga2O3/gallium-indium eutectic junctions. ACS Nano 6, 4806–4822 (2012).

Wang, D. et al. Tuning the tunnelling rate and dielectric response of sam-based junctions via a single polarizable atom. Adv. Mater. 27, 6689–6695 (2015).

Crivillers, N., Mas-Torrent, M., Vidal-Gancedo, J., Veciana, J. & Rovira, C. Self-assembled monolayers of electroactive polychlorotriphenylmethyl radicals on Au(111). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 5499–5506 (2008).

Simão, C., Mas-Torrent, M., Veciana, J. & Rovira, C. Multichannel molecular switch with a surface-confined electroactive radical exhibiting tunable wetting properties. Nano Lett. 11, 4382–4385 (2011).

Crivillers, N. et al. Self-assembled monolayers of a multifunctional organic radical. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 2215–2219 (2007).

Simão, C. et al. A robust molecular platform for non-volatile memory devices with optical and magnetic responses. Nat. Chem. 3, 359–364 (2011).

Frisneda, R. et al. Kondo effect in a neutral and stable all organic radical single molecule break junction. Nano Lett. 15, 3109–3114 (2015).

Ballester, M., Riera-Figueras, J., Castañer, J., Badfa, C. & Monso, J. M. Inert carbon free radicals. I. Perchlorodiphenylmethyl and perchlorotriphenylmethyl radical series. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93, 2215–2225 (1971).

Crivillers, N. et al. Dramatic influence of the electronic structure on the conductivity through open- and closed-shell molecules. Adv. Mater. 21, 1177–1181 (2009).

Crivillers, N. et al. Negative differential resistance (NDR) in similar molecules with distinct redox behaviour. Chem. Commun. 47, 4664–4666 (2011).

Rovira, C. et al. Influence of topology on the long-range electron-transfer phenomenon. Chem. Eur. J. 7, 240–250 (2001).

Yuan, L., Jiang, L., Zhang, B. & Nijhuis, C. A. Dependency of the tunnelling decay coefficient in molecular tunnelling junctions on the topography of the bottom electrodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 3377–3381 (2014).

Weiss, E. A. et al. Influence of defects on the electrical characteristics of mercury-drop junctions: Self-assembled monolayers of n-alkanethiolates on rough and smooth silver. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 4336–4349 (2007).

Weiss, E. A. et al. Si/SiO2-Templated formation of ultraflat metal surfaces on glass, polymer, and solder supports: Their use as substrates for self-assembled monolayers. Langmuir 23, 9686–9694 (2007).

Shekhah, O. et al. Grafting of monocarboxylic substituted polychlorotriphenylmethyl radicals onto a COOH-functionalized self-assembled monolayer through copper (II) metal ions. Langmuir 24, 6640–6648 (2008).

Mugnaini, V. et al. Looking inside the perchlorinated trityl radical/metal spinterface through spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 2101–2106 (2015).

Wimbush, K. S. et al. Bias induced transition from an ohmic to a non-ohmic interface in supramolecular tunnelling junctions with Ga2O3/EGaIn top electrodes. Nanoscale 6, 11246–11258 (2014).

Yaffe, O. et al. Charge transport across metal/molecular (alkyl) monolayer-Si junctions is dominated by the LUMO level. Phys. Rev. B 85, 045433 (2012).

Chiechi, R. C., Weiss, E. A., Dickey, M. D. & Whitesides, G. M. Eutectic gallium–indium (EGaIn): a moldable liquid metal for electrical characterization of self-assembled monolayers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 142–144 (2008).

Simeone, F. C. et al. Defining the value of injection current and effective electrical contact area for egain-based molecular tunnelling junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 18131–18144 (2013).

Yuan, L. et al. Controlling the direction of rectification in a molecular diode. Nat. Commun. 6, 7324 (2015).

Yuan, L., Jiang, L., Thompson, D. & Nijhuis, C. A. On the remarkable role of surface topography of the bottom-electrodes in blocking leakage currents in molecular diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6554–6557 (2014).

Nijhuis, C. A., Reus, W. F., Barber, J. R. & Whitesides, G. M. Comparison of SAM-based junctions with Ga2O3/EGaln top electrodes to other large-area tunnelling junctions. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 14139–14150 (2012).

Wan, A., Jiang, L., Sangeeth, C. S. S. & Nijhuis, C. A. Reversible soft top-contacts to yield molecular junctions with precise and reproducible electrical characteristics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 4442–4456 (2014).

Nijhuis, C. A., Reus, W. F. & Whitesides, G. M. Mechanism of rectification in tunnelling junctions based on molecules with asymmetric potential drops. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 18386–18401 (2010).

Akkerman, H. B. et al. Electron tunnelling through alkanedithiol self-assembled monolayers in large-area molecular junctions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 11161–11166 (2007).

Jiang, L., Sangeeth, C. S. S., Wan, A., Vilan, A. & Nijhuis, C. A. Defect scaling with contact area in egain-based junctions: impact on quality, joule heating, and apparent injection current. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 960–969 (2015).

Simmons, J. G. Generalized formula for electric tunnel effect between similar electrodes separated by a thin insulating film. J. Appl. Phys. 34, 1793–1803 (1963).

Salomon, A. et al. Comparison of electronic transport measurements on organic molecules. Adv. Mater. 15, 1881–1890 (2003).

Choi, S. H., Kim, B. S. & Frisbie, C. D. Electrical resistance of long conjugated molecular wires. Science 320, 1482–1486 (2008).

Yoon, H. J. et al. Rectification in tunnelling junctions: 2,2'-bipyridyl-terminated n-alkanethiolates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 17155–17162 (2014).

Moth-Poulsen, K. & Bjørnholm, T. Molecular electronics with single molecules in solid-state devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 551–556 (2009).

Yuan, L., Breuer, R., Jiang, L., Schmittel, M. & Nijhuis, C. A. A molecular diode with a statistically robust rectification ratio of three orders of magnitude. Nano Lett. 15, 5506–5512 (2015).

Tour, J. M. et al. Self-assembled monolayers and multilayers of conjugated thiols, alpha,omega-dithiols, and thioacetyl-containing adsorbates - understanding attachments between potential molecular wires and gold surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 9529–9534 (1995).

Ishida, T. et al. High-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectra of organosulfur monolayers on Au(111): S(2p) spectral dependence on molecular species. Langmuir 15, 6799–6806 (1999).

Watcharinyanon, S. et al. Molecular orientation of thiol-derivatized tetraphenylporphyrin on gold studied by XPS and NEXAFS. Surf. Sci. 603, 1026–1033 (2009).

Stohr, J. NEXAFS Spectroscopy (Springer–Verlag, (1992).

Reus, W. F. et al. Statistical tools for analyzing measurements of charge transport. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 6714–6733 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore under its Medium sized centre programme, and for the NRF fellowship to C.A.N., award No. NRF-RF 2010-03, is kindly acknowledged for supporting this research. C.F., N.C., M.M.-T., C.R. and J.V. acknowledge the CSIC funded i-LINK0841project, the EU FP7 program through ACMOL collaborative project (GA n° 618082), ERC StG 2012-306826 e-GAMES, CIG (PCIG10-GA-2011-303989) and ITN iSwitch (GA no. 642196), the financial support from the DGI (Spain) (CTQ2013-40480-R), Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, through the ‘Severo Ochoa’ Programme for Centres of Excellence in R&D (SEV-2015-0496), the Generalitat de Catalunya (2014SGR-17) and the Networking Research Center of Bioengineering, Biomaterials and Nanomedicine (CIBER-BBN); N.C. acknowledges the RyC program; C.F. is enroled in the Materials Science PhD program of UAB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.F. synthesized the compounds. N.C. prepared and electrochemically characterized the SAMs and participated in the J(V) measurements performed by L.Y., L.C. and L.Y. recorded and analysed the ARXPS, UPS and NEXAFS spectra. C.S.S.S. and L.Y. performed the temperature-dependent J(V) measurements. M.M.-T., C.R., J.V. and C.A.N. supervised the project. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-19, Supplementary Tables 1-3 and Supplementary Methods. (PDF 2893 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, L., Franco, C., Crivillers, N. et al. Chemical control over the energy-level alignment in a two-terminal junction. Nat Commun 7, 12066 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12066

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12066

This article is cited by

-

Low Tunneling Decay of Iodine-Terminated Alkane Single-Molecule Junctions

Nanoscale Research Letters (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.