Abstract

Silicene, a two-dimensional honeycomb network of silicon atoms like graphene, holds great potential as a key material in the next generation of electronics; however, its use in more demanding applications is prevented because of its instability under ambient conditions. Here we report three types of bilayer silicenes that form after treating calcium-intercalated monolayer silicene (CaSi2) with a BF4− -based ionic liquid. The bilayer silicenes that are obtained are sandwiched between planar crystals of CaF2 and/or CaSi2, with one of the bilayer silicenes being a new allotrope of silicon, containing four-, five- and six-membered sp3 silicon rings. The number of unsaturated silicon bonds in the structure is reduced compared with monolayer silicene. Additionally, the bandgap opens to 1.08 eV and is indirect; this is in contrast to monolayer silicene which is a zero-gap semiconductor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A frenzy of interest in graphene has spawned many theoretical and experimental studies1,2,3,4. After calculating the structures of two-dimensional (2D) crystals of silicon (silicene)5,6,7, researchers have speculated that silicon atoms might form graphene-like sheets and have attempted to produce such silicene structures8,9,10,11,12. Very recently, Tao et al.13 succeeded in fabricating the first silicene transistor, although the device’s performance was modest. Nonetheless, the development of much more facile and practical processing methods has remained a challenging issue. The most difficult problem is that silicene grows on specific substrates and is stable only under vacuum conditions8,9,14,15. Another issue is that the influence of the substrate cannot be removed; the strong hybridization between Si and the substrate may stabilize silicene grown on specific substrates8,14,15,16.

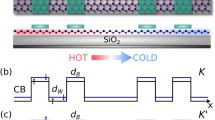

In a previous report on calcium-intercalated silicene (CaSi2), we observed a massless Dirac-cone band dispersion at the k-point in the Brillouin zone, which was located far from the Fermi level because of the substantial charge transfer from the Ca atoms to the silicene layers17. This result is similar to the previously reported band structures of silicenes deposited on specific substrates9 because CaSi2 is a type of Zintl silicide, in which the formal charge is rewritten as Ca2+ and Si− (ref. 18). Therefore, the intrinsic electronic structure of silicene has never been observed. In the calculated results, a van der Waals bonded silicene layer has been deposited on an intact multi-CaF2 layer19. If the Ca layer of CaSi2 had been exchanged with a CaF2 layer, the influence of the substrate would have been almost completely suppressed. To reduce the influence of external factors on the electronic structure of silicene (for example, from substrates or counter ions) and to increase the stability under ambient condition, we replaced monolayer silicene with bilayer silicene.

The existence of a bilayer silicene structure, whose density of unsaturated silicon bonds is reduced in comparison with monolayer silicene, has been predicted by molecular dynamics (MD) calculations20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. If we could experimentally prepare a similar bilayer silicene, we could then investigate its intrinsic electronic structure. Because of the electron transfer from the calcium cation, the monolayer silicene in CaSi2 is a formally anionic layer17: when the calcium cation becomes electrically neutral, the silicene will not retain its honeycomb structure and will reconstruct to form a more stable structure. Under this supposition, we attempted to segregate the Ca and Si phases while maintaining the layer structures by diffusing fluoride (F) atoms, which are more electronegative than Si, into CaSi2; the goal was to form an ionic bond (or interaction) between Ca and F. In this study, BF4 anion based ionic liquid was used for the origin of fluoride anion.

Results

Fluoride diffusion into CaSi2

When the CaSi2 crystal (Supplementary Fig. 1) was annealed in [BMIM][BF4] ionic liquid at 250–300 °C, it was changed to a CaSi2FX (0≤X≤2.3) compound through diffusion of F−, in which the local F− concentration gradually decreased from the crystal edge to the interior (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Fig. 2). As a result, three types of bilayer Si in a CaSi2 single crystal were obtained by diffusion of F−. Figure 1c, which displays a high-angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image taken of the CaSi2F1.8 compound, shows the alternate stacking of planar crystal domains with layer thicknesses of 1–2 nm. The HAADF-STEM imaging provided an atomic-scale Z-contrast image (Z: atomic number) to distinguish the heavier constituent elements28,29,30. STEM-energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (STEM-EDX) elemental mapping identified the bright-contrast crystal domains, which were identified as the CaF2 phase and the dark domains, which were identified as Si phases (Fig. 1f–j). We determined the crystal structures of the entire planar region in the images of the CaSi2F1.8 and CaSi2F2.0 compounds shown in Fig. 1c,d, respectively. These planar domains were identified as trilayer CaF2, trilayer Si, bilayer CaF2 and a novel bilayer silicene (denoted as w-BLSi in Fig. 1c,d) that has not been previously predicted by MD calculations20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Furthermore, two types of bilayer silicenes, one with inversion symmetry (i-BLSi) and one with mirror symmetry (m-BLSi), were recognized in the CaSi2F0.6-1.0 composition area (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 3). The formation of m-BLSi is in accordance with predictions from a previous MD study22. The i- and m-BLSi must be adjacent to a pair of CaF2 and CaSi2 crystal layers. The abundance ratio of i-BLSi to m-BLSi was 124:3 in the observed HAADF-STEM images. Because the calculated energy of i-BLSi was 0.03 eV per atom lower than that of m-BLSi under vacuum, the abundance ratio is qualitatively reasonable. The average size of w-BLSi is ∼30 nm, and that of m-BLSi is ∼10 nm. The size of i-BLSi is greater than 51 nm, which is the maximum size that can be observed by STEM imaging.

(a) Cross-sectional BSE image of the crystal grain including CaSi2FX compound. (b) EPMA quantitative line analysis result along the red arrow in a. (c) HAADF-STEM image taken from a region with CaSi2F1.8 in b; the strip contrast corresponds to Si (dark domain) and CaF2 (bright domain) planar crystals. (d) An enlarged HAADF-STEM image taken from a region with CaSi2F2 in b; red arrows indicate an F-vacancy site. (e) HAADF-STEM image taken from a region with CaSi2F0.6-1.0 in b; bright dots, corresponding to the projected atomic positions of m-and i-BLSi, can be observed in the image. (f–i) STEM-EDX elemental mapping results of the CaSi2F2 composition region. One-element mapping (f: Si; g: Ca; and h: F). (i) Overlapped-mapping of Si, Ca and F. (j) HAADF-STEM image of the STEM-EDX elemental mapping area. The scale bars in a; c and j; and d and e; 100 μm, 2 nm and 1 nm.

Structural determination of w-BLSi

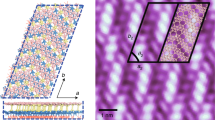

The atomic structure of the bilayer silicene was determined from HAADF-STEM images that were taken with different incident electron beam directions (Fig. 2a–c, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 1). As shown in Fig. 2d, the bilayer silicene structure had a 2D translation symmetry and a wavy morphology (hereafter, we refer to the structure as w-BLSi). The w-BLSi structure consists of two silicenes, with alternating chair and boat conformations, that are vertically connected via four-, five- and six-membered rings. Because w-BLSi consists of only Si atoms exhibiting tetrahedral coordination, the top atom of the five-membered silicon ring possesses unsaturated silicon bonds (dangling bonds). Therefore, compared with those in monolayer silicene and i- (or m-) BLSi, the density of unsaturated silicon bonds in w-BLSi decreased to 25 and 50%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5).

(a–c) HAADF-STEM and simulation (insets) images of w-BLSi. (a) the [01]w-BLSi and [11]w-BLSi incident directions ([1-10]CaF2), (b) the [10]w-BLSi and [11-2]Si and CaF2 directions and (c) the [13]w-BLSi and [11-2]Si and CaF2 directions. (d) Schematic illustration of the w-BLSi atomic structure. (e–h) Schematic structures projected in each direction in e [01], f [13], g [11] and h [10] directions. All scale bars in (a–c), 1 nm.

We determined the atomic positions of w-BLSi from high-resolution transmission electron microscopy and HAADF-STEM images as accurately as possible (Supplementary Figs 6 and 7, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note 2). The 2D translation periods of w-BLSi were a=0.661(2) nm and b=0.382(3) nm, and the two translation axes were normal to each other (Supplementary Fig. 8). The a period of w-BLSi is similar to the triple lattice spacing of d11-2 in CaF2 (0.223 nm), and the b period is similar to d-110 in CaF2 (0.386 nm); that is, the difference between w-BLSi and CaF2 (111) is less than the observation error (Supplementary Fig. 9). Because the atomic arrangement of the (111) plane of the CaF2 crystal exhibited threefold symmetry, three equivalent relative rotation angles were observed between w-BLSi and the CaF2 (111) plane (Supplementary Figs 10 and 11). In addition, the angle between the [01]w-BLSi and [11]w-BLSi directions was almost 60° (Supplementary Fig. 10, w-BLSi is described in 2D notation, because 2D can be expressed more simply than three dimensions). Therefore, Figs 1c and 2a show the contrast of two different arrangements of bright dots—specifically, the [01] and [11] direction images (Fig. 2e,g) in the w-BLSi regions. In almost all of the observed HAADF-STEM images, w-BLSi always faced the (111) plane of CaF2, and the F vacancies (red arrows in Fig. 1d) on the CaF2 (111) surface were recognized at special positions associated with the wavy structure of w-BLSi. A w-BLSi was observed to be sandwiched between two CaF2 layers with an F-site surface vacancy of ∼0.5 at the interface (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Figs 7,12–15 and Supplementary Note 3).

DFT and ab initio MD calculations and optical properties

The w-BLSi structure appears to resemble re-BLSi20 in appearance; however, its atomic arrangement is clearly different (Supplementary Fig. 16). An ab initio MD calculation was performed for BLSi under the conditions corresponding to the experimentally observed structure, that is, BLSi was sandwiched between two CaF2 layers with an F-site surface vacancy of 0.5 at the interface. The MD calculation was started with the i-BLSi structure, but it was immediately transformed to another BLSi structure. The system was then equilibrated, and the resultant BLSi structure was found to perfectly agree with the experimentally observed w-BLSi structure in Fig. 3a (Supplementary Tables 2–5, Supplementary Fig. 17 and Supplementary Note 4). The electronic density of states (DOS) for w-BLSi was calculated by using the structure in Fig. 3a, and the decomposed DOSs for Si, Ca, and F are shown in Fig. 3b. The Ca and F bands are located far below the Fermi level, and the valence bands consist of only Si bands. An ionic rather than a covalent interaction is thus expected between Si and Ca or F. We also observe that the bandgap opens to ∼0.65 eV, in contrast to monolayer silicene, which is a zero-gap semiconductor31. Interestingly, however, the gap closes when w-BLSi is isolated without geometry optimization under vacuum (Supplementary Fig. 18b). This result indicates that, in the CaSi2FX compound, charge transfer from Ca to Si occurs, filling the energy levels that are unoccupied under vacuum (Supplementary Discussion). Thus, the electronic properties of w-BLSi appear to be sensitive to its environmental conditions.

(a) Structure of w-BLSi sandwiched between two CaF2 crystals, with vacancies at half of the F sites on the interface; this structure was used to calculate the DOS and was obtained from the transformation of i-BLSi in the ab initio MD simulation and the subsequent quenching process (Supplementary Method). (b) Decomposed DOS for Si, Ca and F in w-BLSi displayed in a. (c) Plot of multiplication of the K/S and energy as a function of energy for CaSi2F1.8-2.3 consisting of w-BLSi, trilayer silicene with dangling bonds and F-terminated trilayer silicene. The absorption spectrum suggests two indirect gaps with values of 1.08 and 1.78 eV.

The presence of the F vacancies allows the electrons on Ca to transfer to Si, which enhances the stability of the w-BLSi structure (Fig. 3a) by saturating the dangling bonds. The CaF2-X domains (specifically, ionic crystalline domains) surrounding the Si layers are key to the formation of the w-BLSi structure.

The optical bandgap can be calculated from the absorption spectrum. The diffuse reflectance spectrum of the powder sample with CaSi2F1.8-2.3 composition was measured, and the obtained reflectance spectrum data (Supplementary Fig. 19) were converted to a Kubelka–Munk function (K/S), which is proportional to the absorption coefficient (α). The sample was a mixture of w-BLSi, two types of trilayer silicene (with dangling bonds and terminated with F atoms, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 20) and a CaF2 layer (Supplementary Note 5). The relationship between the absorption coefficient (α) and the bandgap energy (Eg) can be described by two types of equations: αhν=const (direct gap) and αhν=A (hν−Eg) (indirect gap), where the DOS for 2D crystals is constant as a function of energy32,33,34,35 (Supplementary Note 5). Here, h, ν and A are Planck's constant, light frequency and proportional constant, respectively. From two linear fittings of the spectrum, the latter equation was found to be suitable for the sample. The absorption edges of the CaSi2F1.8-2.3 compound were observed at 1.08 and 1.78 eV (Fig. 3c), assuming indirect transitions.

Freestanding trilayer silicene is semi-metallic, as shown by density functional theory (DFT) calculations36. It has been suggested that the bandgap of trilayer silicene with dangling bonds in CaSi2F1.8-2.3 is nearly zero if charge transfer between the trilayer silicene and the CaF2 layer is inhibited19. From previous DFT results of monolayer and multilayer silicene terminated with atoms37,38, it is conjectured that the bandgap of F-terminated trilayer silicene would be ∼1 eV within the framework of the DFT and Perdew, Burke and Ernzerhof (PBE) technique. It should be noted that DFT calculations using a standard generalized gradient approximation functional tend to underestimate the bandgap (roughly ∼2/3 in crystal Si). This indicates that the bandgap experimentally measured for the trilayer silicene should be ∼1.5 eV. Meanwhile, the bandgap for w-BLSi, which is estimated to be ∼ 0.65 eV in the DFT–PBE calculation, is expected to be ∼1 eV in the experimental measurement. Therefore, the measured gaps were estimated such that the gaps of w-BLSi and F-terminated trilayer silicene were 1.08 and 1.78 eV, respectively.

Transformation process from monolayer silicene to w-BLSi

On the basis of the HAADF-STEM data, we discussed a model for the transformation process from a monolayer silicene in CaSi2 (Fig. 4a) to w-BLSi (Fig. 4f). When F− ions diffuse from the surface of a CaSi2 crystallite into the crystal along the Ca layer, thin CaF2-x planar crystals are formed; as a result, anionic silicene layers assemble to reduce the number of unsaturated bonds beyond the Ca layer (Fig. 4b). During this movement, the Si covalent bonding network with honeycomb symmetry is broken and its arrangement consequently becomes random (Fig. 4c). As shown in Fig. 4d, two types of bilayer silicenes, i-BLSi and m-BLSi, which formed in the slit-like regions, as predicted by the MD calculation22, co-exist with CaSi2 in the low F-concentration region. Both of these structures are stabilized as a result of charge transferred from the Ca atoms which saturate the silicon dangling bonds.

(a) and (d–f) HAADF-STEM image. (b,c) A schematic model. (a) Raw tr6 CaSi2. (b) F diffusion into CaSi2. (c) A random arrangement of i-BLSi and bilayer CaF2-X in CaSi2. (d) i-BLSi, CaF2-X and CaSi2 in a region with CaSi2F0.6-1.0. (e) i-BLSi and w-BLSi formed within the same layers in CaSi2F0.6-1.0. (f) w-BLSi in CaSi2F2.0. All scale bars, 1 nm.

We analysed more than 200 STEM images of BLSi; w-BLSi was recognized at F concentrations surpassing that of CaSi2F1.8. With increasing F concentration, the site occupancy of F concentration at the interface of the CaF2 planar crystal reached ∼0.5, then w-BLSi was formed by the change of ionic interactions among Si, Ca and F (Fig. 3e,f). In this process, negatively charged Si atoms tend to lose their electrons, which makes i- (or m-) BLSi less stable because the ‘capping’ of the dangling bonds by extra electrons from Ca is reduced and the dangling bonds destabilize the sp3 tetrahedral configuration. Thus, the anionic honeycomb structure of i- (or m-) BLSi is transformed to w-BLSi, which is approximately neutral because of the fluorination of the Ca cation.

Discussion

We focused on calcium-intercalated silicene (CaSi2) and discovered a strategy for transforming monolayer silicene into a novel bilayer silicene (w-BLSi). From HAADF-STEM images, we observed that w-BLSi was formed between the planar crystals of CaF2 and contained four-, five- and six-membered silicon rings, although w-BLSi consists of only Si atoms exhibiting tetrahedral coordination. Compared with monolayer silicene, the number of unsaturated silicon bonds in w-BLSi decreased to 25% of the unit cell. The transformation process from monolayer silicene in CaSi2 to w-BLSi was estimated from HAADF-STEM data. When F− ions diffuse into the CaSi2 crystal along the Ca layer, thin CaF2-x planar crystals and two types of bilayer silicenes (i-BLSi and m-BLSi) are formed, following breakage of the Si covalent bonding monolayer network. Both of these Si structures were stabilized as a result of charge transferred from the Ca atoms which saturate the silicon dangling bonds. With increasing F content, i- (or m-) BLSi is transformed to w-BLSi. Additionally, the structure possesses an indirect bandgap of 1.08 eV in contrast to monolayer silicene, which is a zero-gap semiconductor.

Methods

Synthesis of CaSi2FX compound

CaSi2 single-crystal grains (0.1 g) were reacted with 5 ml of ionic liquid [BMIM][BF4] (1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate) at 300 °C for 15 h. BF4− decomposed into F− during annealing, and the CaSi2 crystal was changed to CaSi2FX compounds (0≤X≤2.3) through the diffusion of F− (Fig. 1a,b). More details are given in Supplementary Method.

Chemical composition analysis

The chemical compositions of the CaSi2FX domains were determined by electron probe microanalyser (EPMA) with a wave dispersion system (JEOL JXA-8200), an accelerating voltage of 10 kV, a specimen current of 50 nA, and an electron irradiation area of 5 μmϕ. Single-phase CaF2 and Si crystals were used as the standard for quantitative composition analysis of Ca, F and Si. EPMA line analyses were performed with 5 μm steps from the edge to the inside of the CaSi2FX crystallites cross-sectioned parallel to the CaSi2 [001] direction.

TEM/STEM analysis

HAADF-STEM observations28,29,30 and STEM energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analyses were performed with a Titan3. G2 60–300 electron microscope (FEI, Cs=156 nm) operated at 300 kV. HAADF-STEM imaging was capable of providing an atomic-scale Z-contrast image associated with the heavier constituent elements. The annular detector was set to collect the electrons scattered at angles between 50.5 and 200 mrad. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy observations were obtained with a JEM-2000EX electron microscope (JEOL, Cs=0.7 mm) operating at 200 kV. TEM specimens of CaSi2FX were detected with five different F concentration ranges (CaSi2F0.6-1.0, CaSi2F1.6, CaSi2F1.8, CaSi2F2.0 and CaSi2F2.3) by using the FIB micro-sampling method39. The atomic positions in the w-BLSi crystal and the interface structure were characterized by comparing the HAADF-STEM image contrasts with simulated contrasts calculated by the multi-slice method using MacTempasX.

Computational method

DFT and ab initio MD calculations were performed to calculate the DOS and to examine the structural stability of BLSi using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (ref. 40). The projector augmented wave method41 and generalized gradient approximation with the exchange and correlation functions of PBE were employed42. A plane-wave basis set with an energy cutoff of 400 eV was used with Γ-point sampling in the Brillouin zone. To model the BLSi systems observed in our experiments, two-layer Si structures were sandwiched by CaF2 crystal domains, each consisting of three sets of CaF2 layers, with or without the F-site vacancy at the Si/CaF2 interfaces. The DOS for the w-BLSi was calculated for the structure obtained after the quenching process (shown in Fig. 3a) following the 300 K run. More details are given in Supplementary Method.

Optical reflectivity

Diffuse reflectance spectra were obtained for the CaSi2F1.8-2.3 composition powder sample using a spectrophotometer (JASCO V-670).

The diffuse reflectance spectra were processed under the Kubelka–Munk formalism, and the bandgaps were determined using a plot of the multiplication of the K/S and energy. More details are given in Supplementary Methods.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yaokawa, R. et al. Monolayer-to-bilayer transformation of silicenes and their structural analysis. Nat. Commun. 7:10657 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10657 (2016).

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Two-dimensional gas of massless dirac fermions in graphene. Nature 438, 197–200 (2005).

Zhang, Y., Tan, Y. W., Stormer, H. L. & Kim, P. Experimental observation of the quantum hall effect and berry’s phase in graphene. Nature 438, 201–204 (2005).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Room-temperature quantum Hall Effect in Graphene. Science 315, 1379 (2007).

Takeda, K. & Shiraishi, K. Theoretical possibility of stage corrugation in Si and Ge analogs of graphite. Phy. Rev. B 50, 14916 (1994).

Cahangirov, S., Topsakal, M., Aktürk, E., Şahin, H. & Ciraci, S. Two- and one-dimensional honeycomb structures of silicon and germanium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 236804 (2009).

Lebègue, S. & Eriksson, O. Electronic structure of two-dimensional crystals from ab initio theory. Phys. Rev. B 79, 115409 (2009).

Vogt, P. et al. Silicene: Compelling experimental evidence for graphenelike two-dimensional silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 155501 (2012).

Fleurence, A. et al. Experimental evidence for epitaxial silicene on diboride thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 245501 (2012).

Okamoto, H. et al. Silicon nanosheets and their self-assembled regular stacking structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 2710–2718 (2010).

Sugiyama, Y. et al. Synthesis and optical properties of monolayer organosilicon nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5946–5947 (2010).

Okamoto, H., Sugiyama, Y. & Nakano, H. Synthesis and modification of silicon nanosheets and other silicon nanomaterials. Chem. Eur. J. 17, 9864–9887 (2011).

Tao, L. et al. Silicene field-effect transistors operating at room temperature. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 227–231 (2015).

Morishita, T., Spencer, M. J. S., Kawamoto, S. & Snook, I. K. A new surface and structure for silicene: polygonal silicene formation on the Al(111) surface. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 22142–22148 (2013).

Gao, J. & Zhao, J. Initial geometries, interaction mechanism and high stability of silicene on Ag(111) surface. Sci. Rep. 2, 861 (2012).

Cahangirov, S. et al. Electronic structure of silicene on Ag(111): strong hybridization effects. Phys. Rev. B 88, 035432 (2013).

Noguchi, E. et al. Direct observation of dirac cone in multilayer silicene intercalation compound CaSi2 . Adv. Mater. 27, 856–860 (2015).

Yaokawa, R., Nakano, H. & Ohashi, M. Growth of CaSi2 single phase polycrystalline ingots using the phase relationship between CaSi2 and associated phases. Acta Mater. 81, 41–49 (2014).

Kokott, S., Pflugradt, P., Matthes, L & Bechstedt, F. Nonmetallic substrates for growth of silicene: an ab initio prediction. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 26, 185002 (2014).

Morishita, T., Spencer, M. J. S., Russo, S. P., Snook, I. K. & Mikami, M. Surface reconstruction of ultrathin silicon nanosheets. Chem. Phys. Lett. 506, 221–225 (2011).

Sakai, Y. & Oshiyama, A. Structural stability and energy-gap modulation through atomic protrusion in freestanding bilayer silicene. Phy. Rev. B 91, 201405(R) (2015).

Morishita, T., Nishio, K. & Mikami, M. Formation of single- and double-layer silicon in slit pores. Phy. Rev. B 77, 081401(R) (2008).

Bai, J., Tanaka, H. & Zeng, X. C. Graphene-like bilayer hexagonal silicon polymorph. Nano Res 3, 694–700 (2010).

Johnston, J. C., Phippen, S. & Molinero, V. A single-component silicon quasicrystal. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 384–388 (2011).

Pflugradt, P., Matthes, L. & Bechstedt, F. Unexpected symmetry and AA stacking of bilayer silicene on Ag(111). Phys. Rev. B 89, 205428 (2014).

Guo, Z.-X. & Oshiyama, A. Structural tristability and deep Dirac states in bilayer silicene on Ag(111) surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 89, 155418 (2014).

Cahangirov, S. et al. Atomic structure of the phase of silicene on Ag(111). Phys. Rev. B 90, 035448 (2014).

Pennycook, S. J. & Jesson, D. E. High-resolution incoherent imaging of crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett 64, 938–941 (1990).

Pennycook, S. J. & Jesson, D. E. High-resolution z-contrast imaging of crystals. Ultromicroscopy 37, 14–38 (1991).

Pennycook, S. J. & Jesson, D. E. Atomic resolution Z-contrast imaging of interfaces. Acta Mater. 40, S149–S159 (1992).

Huang, S., Kang, W. & Yang, L. Electronic structure and quasiparticle bandgap of silicene structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 133106 (2013).

Lee, P. A., Said, G., Davis, R. & Lim, T. H. On the optical properties of some layer compounds. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 30, 2719–2729 (1969).

Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Gaiser, C. et al. Band-gap engineering with HfSXSe2√X . Phys. Rev. B 69, 075205 (2004).

Bianco, E. et al. Stability and exfoliation of germanane: a germanium graphane analogue. ACS Nano 7, 4414–4421 (2013).

Kamal, C., Chakrabarti, A., Banerjee, A. & Deb, S. K. Silicene beyond mono-layers —different stacking configurations and their properties. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 25, 085508 (2013).

Gao, N., Zheng, W. T. & Jiang, Q. Density functional theory calculations for two-dimensional silicene with halogen functionalization. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 257–261 (2012).

Morishita, T. et al. First-principles study of structural and electronics properties of ultrathin silicon nanosheets. Phys. Rev. B 82, 045419 (2010).

Kirk, E. C. G., Williams, D. A. & Ahmed, H. Cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy of precisely selected regions from semiconductor devices. Inst. Phys. Conf. Ser. 100, 501–506 (1989).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by PRESTO, the Japan Science and Technology Agency, and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. HAADF-STEM observations in this work were supported by the ‘Nanotechnology Platform’ of MEXT, Japan, at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnology Support, Tohoku University. The computations were undertaken with the assistance of resources from the National Computational Infrastructure (NCI), which is supported by the Australian Government, the Pawsey Supercomputing Centre with funding from the Australian Government and the Government of Western Australia, the Multi-modal Australian ScienceS Imaging and Visualisation Environment (MASSIVE) and the Victorian Partnership for Advanced Computing Limited (VPAC Ltd) through the V3 Alliance, Australia, and at the computational facilities at the Research Center for Computational Science, National Institute of Natural Sciences, and at the Research Institute for Information Technology, Kyushu University, Japan. We thank Mr Y. Yagi for the EPMA measurements, Prof. S. Yamanaka and Dr Y. Takeda for fruitful discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.Y. and H.N. conceived the idea. R.Y. and T.O. designed the experiments. R.Y. synthesized the CaSi2 single crystals and CaSi2FX compounds. Y.H. performed the HAADF-STEM observations and the EDX analyses. T.M. and M.J.S.S. performed the theoretical work. R.Y. and T.O. characterized the w-BLSi. R.Y., T.O., T.M. and H.N. wrote the manuscript. All the authors have read the manuscript and agree with its content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-20, Supplementary Tables 1-5, Supplementary Notes 1-5, Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 2045 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yaokawa, R., Ohsuna, T., Morishita, T. et al. Monolayer-to-bilayer transformation of silicenes and their structural analysis. Nat Commun 7, 10657 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10657

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10657

This article is cited by

-

Enhancement of absorption in a CH3NH3PbI3-based photonic crystal in the presence of the monolayer MoS2

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Rich Magnetic Quantization Phenomena in AA Bilayer Silicene

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Oxidative reactivity of alkali-like superatoms of group 5 metal-encapsulating Si16 cage nanoclusters

Communications Chemistry (2018)

-

Theoretical design of sandwich two-dimensional structures for photocatalysts and nano-optoelectronic devices

Journal of Materials Science (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.