Abstract

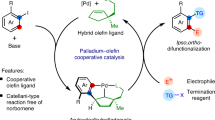

Currently, great interest is focused on developing auto-tandem catalytic reactions; a substrate is catalytically transferred through mechanistically distinct reactions without altering any reaction conditions. Here by incorporating a pyrrolidine moiety as a chiral organocatalyst and a polyoxometalate as an oxidation catalyst, a powerful approach is devised to achieve a tandem catalyst for the efficient conversion of CO2 into value-added enantiomerically pure cyclic carbonates. The multi-catalytic sites are orderly distributed and spatially matched in the framework. The captured CO2 molecules are synergistically fixed and activated by well-positioned pyrrolidine and amine groups, providing further compatibility with the terminal W=O activated epoxidation intermediate and driving the tandem catalytic process in a single workup stage and an asymmetric fashion. The structural simplicity of the building blocks and the use of inexpensive and readily available chemical reagents render this approach highly promising for the development of practical homochiral materials for CO2 conversion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, the selective and efficient conversion of light olefins with CO2 as a C1 building block into value-added enantiomerically pure cyclic carbonates has attracted great interest from chemists and governments due to its tremendous potential economic and environmental impact, especially considering the increasing worldwide greenhouse effect1. The general synthetic procedure includes two mechanistically distinct catalytic processes consisting of the asymmetric epoxidation of olefins, based on the research of Sharpless and others, and the asymmetric coupling epoxide with CO2 (refs 2, 3, 4, 5). Both of the catalytic processes require asymmetric (or associated) catalysts to ensure enantioselectivity, as well as a sequential separation and purification process of the products from the reagents, the catalysts and the associated materials. Because light olefins are the most inexpensive and readily available chemical building blocks, a one-pot procedure that processes an olefin through a chain of discrete catalytic steps with multiple transformations using a single workup stage is highly desirable for the environmentally benign conversion of carbon dioxide to fine chemicals6.

Inspired by natural enzymatic processes, chemists have attempted to emulate natural reaction cascades by developing auto-tandem catalytic reactions in which a substrate is catalytically transferred through two or more mechanistically distinct reactions without the addition of reactants or catalysts and without altering the reaction conditions7,8. Recently, homogeneous organo- and organometallic auto-tandem catalysts have been found to show high efficiency in solution9. This feature can be advantageous for separation and catalyst recovery by creating heterogenized catalysts using linkers to attach them to a support, such as high surface-area metal oxide materials, or alternatively, incorporating them within porous metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). One of the key advantageous of MOFs lies in their easily tunable composition in which the constituents’ geometry, size and functionality can be widely varied10,11,12. Thus, an ongoing challenge for the development of auto-tandem catalytic processes has been beyond the selection and incorporation of two or more catalytic sites by modifying these moieties in the building block of the original MOFs, but includes the achievement of compatibility between the reaction intermediates and synergy of the multiple catalytic cycles13,14,15.

Polyoxometalates (POMs) are well-known catalysts studied in olefin epoxidation, with excellent thermal and oxidative stability towards oxygen donors16,17,18. By combining chiral organic catalysts and POM components in a single MOF (POMOF), these POMOF materials can initiate the asymmetric dihydroxylation of aryl olefins with excellent stereoselectivity19. Because MOFs have exhibited unrivalled efficiency as heterogeneous Lewis acid catalysts for the chemical conversion of CO220,21,22,23, we envision that the combination of chiral organic catalysts, Lewis acid catalysts and oxidation catalysts would be a powerful approach to devise a tandem catalytic process for the chemical transformation of olefins to chiral cyclic carbonate.

By incorporating Keggin-type [ZnW12O40]6− anions, zinc(II) ions, NH2-functionalized bridging links, NH2-bipyridine (NH2-BPY) and asymmetric organocatalytic groups, pyrrolidine-2-yl-imidazole (PYI) within one single MOF, herein we report the design and synthesis of two new enantiomorphs of POMOFs, ZnW−PYI1 and ZnW−PYI2, for the efficient conversion of CO2 into value-added enantiomerically pure cyclic carbonates. Because the intrinsic crystalline properties could provide precise knowledge about the nature and distribution of catalytically active sites and about the potential interactions between the catalytic sites and the adsorbed substrates, the use of POM-based homochiral MOFs offers the potential to facilitate analysis of the intermediates and the catalytic processes of each step of the tandem asymmetric transformation.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of the POMOFs

The solvothermal reaction of TBA4W10O32, Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, NH2-BPY and L−N-tert-butoxy-carbonyl-2-(imidazole)-1-pyrrolidine (L−BCIP) in a mixed solvent of acetonitrile and H2O gave compound ZnW−PYI1 in a yield of 68% (Supplementary Fig. 1). Elemental analyses and powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) indicated the pure phase of the bulk sample (Supplementary Fig. 2). Circular dichroism spectrum of the bulk sample of ZnW−PYI1 presented positive cotton effects at 276 nm (θ=146 mdeg) and negative cotton effects at 340 nm (θ=−41.2 mdeg). The entire spectrum was different from the spectra of the chiral adducts L−BCIP and L−PYI (Supplementary Fig. 3). ZnW−PYI2 was prepared similarly to ZnW−PYI1, except that D−BCIP replaced L−BCIP. The circular dichroism spectrum of ZnW−PYI2 exhibited the cotton effects that were opposite to ZnW−PYI1, as expected for a pair of enantiomers with a mirror–imager relationship (Fig. 1a). Single-crystal structural analysis revealed that ZnW−PYI1 and ZnW−PYI2 shared the same cell dimensions crystallized in the chiral space group P21 (Supplementary Data 1 and 2, Supplementary Fig. 14–21).

(a) Circular dichroism spectra of bulk crystals of ZnW−PYI1 (black) and ZnW−PYI2 (red), respectively. (b) Plot of the one-dimensional connections between the bipyridine ligands and the zinc centres, showing the coordination mode of the zinc centres. (c) Perspective view of the two-dimensional sheet connected by the polyoxometalate clusters and the zinc centres, the bipyridine ligands were omitted for clarity. (d) 3D open network of ZnW−PYI1 viewed down the b axis. H atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity. Carbon, nitrogen and zinc are drawn in gray (orange for PYI), blue, and cyan, respectively, with ZnW12O406− shown as polyhedra.

The crystal structures of POMOFs

The asymmetric unit of ZnW−PYI1 consists of the Keggin anion ZnW12O406− and the cation [Zn2(NH2-BPY)2(HPYI)2(H2O)(CH3CN)]6+ (Supplementary Fig. 4). The precursor W10O324− anion is labile under hydrothermal conditions and favours to rearrangement into the more stable Keggin-type ZnW12O406− anion. Each of these ZnW12O406− anions connects to four zinc ions through the terminal oxygen atoms and acts as a four connector (Supplementary Fig. 5). Each of the two crystallographically independent zinc ions adopts a distorted octahedral geometry (Supplementary Fig. 6,7) and coordinates to two terminal oxygen atoms from different ZnW12O406− anions, forming a two-dimensional square grid sheet (Fig. 1b,c, Supplementary Fig. 8,9). Each of the NH2-BPY ligands coordinates to two different zinc ions and further bridges the sheets to form a three-dimensional framework with one-dimensional chiral channels along the b axis (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 10,11). The accessible empty space of the framework is approximately 289.1 Å3 (8.1%), as calculated from PLATON analysis, suggesting the possibility that the MOF-based material ZnW−PYI1 can absorb substrates within its pores24. Chiral PYI was located in the pores of the MOF, with the butoxycarbonyl of L−BCIP removed simultaneously in the reaction and the pyrrolidine nitrogen was protonated. The unique redox properties of ZnW12O406−, with its oxygen-enriched surface, provide sufficient driving force for the transformation of the catalytic precursors to the active intermediate of the epoxidation25,26. The chiral PYIs act as cooperative catalytic sites to forge a crucial reaction centre that enhances the activities of the oxidants and drives the catalysis asymmetrically27,28. Detailed structural analyses reveal that one zinc ion has a water molecule at its sixth coordination position, while the other is associated with an acetonitrile molecule. The removability of the coordinated water molecules indicates the potential of ZnW−PYI1 to act as an active Lewis acid catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 12). These amine groups in NH2-BPY are positioned around the inner surface of the channels and act as accessible sites to activate CO2 directly, enabling the catalytic performance in the coupling of carbon dioxide with epoxide under relatively mild conditions (Fig. 2)29,30,31,32.

Separated tandem catalysis

The transformation of asymmetric epoxidation was initially examined using styrene and t-butylhydroperoxide (TBHP, 70% in decane) as the oxidant, along with ZnW−PYI1 (0.1% mol ratio) in a heterogeneous reaction at 50 °C for 5 days. As shown in Table 1 (entries 1–4), the result revealed the successful execution of our POMOF design, showing excellent yield (92%) and enantioselectivity (79% enantiomer excess (ee)) for (R)-styrene oxide (Supplementary Fig. 22, Supplementary Table 6). The control experiments showed that L−PYI and its hydrochloride salt could not initiate the reaction under similar conditions. The use of L−PYI and Zn3[ZnW12O40] as homogeneous catalysts gave a conversion of 55% and an ee value of 18%. The higher conversion in the case of the ZnW−PYI1 system was attributed to the suitable distribution of pairs of the chiral PYI moiety and the ZnW12O406− oxidant catalyst. Infrared of the catalyst impregnated with TBHP revealed a new v(O–O) band at 821 cm−1, which indicated that the active intermediate peroxotungstate was formed during the epoxidation process (Fig. 3a)33. From a mechanistic perspective, the formation of hydrogen bonds between the pyrrolidine N atom and the terminal oxygen atoms of the ZnW12O406− with the interatomic separation N(12)···O(7), approximately 2.8 Å, initially activated the corresponding W=Ot (Ot=terminal oxygen) and generated an active peroxide tungstate intermediate, ensuring the smooth progress of the reaction (Supplementary Table 2–5). These hydrogen bonds then enforced the proximity between the conventional electrophilic oxidant and the chiral directors to provide additional steric orientation, driving the catalysis to proceed in a stereoselective manner19,34.

Solids of ZnW−PYI2 exhibited similar catalytic activities but gave products with the opposite chirality in the asymmetric epoxidation of styrene. The use of such a catalyst can be extended to other substituted styrene substrates and α, β-unsaturated aldehydes with comparable activity and asymmetric selectivity. The presence of a C=O stretching vibration at 1,675 cm−1 (cf. 1682, cm−1of the free aldehyde) in the infrared spectra of the catalyst impregnated with a CH2Cl2 solution of cinnamaldehyde suggested the absorbance and activation of cinnamaldehyde in the cavities of ZnW−PYI1 (Fig. 3b).

The transformation of the asymmetric coupling of CO2 to styrene oxide was examined using the racemic styrene oxide and CO2 in free solvent, along with ZnW−PYI1 (0.1% mol ratio) and cocatalyst TBABr (1% mol ratio), in a heterogeneous mixture at 50 °C and 0.5 MPa for 48 h, as shown in Table 1 (entry 5). The result exhibited excellent reaction efficiency (>99% yield) for phenyl(ethylene carbonate) (Supplementary Table 7). The control experiments demonstrated that no detectable conversion was observed for the model reaction in the absence of ZnW−PYI1 or the ammonium salt cocatalyst. It is postulated that the directed coordination of the ZnW12O406− anion to the zinc ions results in significant activation of the MOF on the acid surface, facilitating the coupling step because of its additional labile ligand sites, possibly through the provision of a carbon dioxide. The surface properties of the nanocation also meet a number of criteria for the carbon dioxide coupling reaction, such as an overall positive charge, the presence of coordinated water and the presence of functional groups for acid catalysis. Enantiospecific phenyl(ethylene carbonate) could be obtained through the coupling of CO2 to the (R) or (S)-styrene oxide, catalysed with excellent reaction efficiency (>99% yield) and high enantioselectivity (>90% ee) (Supplementary Fig. 23, Supplementary Table 8) by ZnW−PYIs (Table 1, entries 6,7). The retention of chirality through the asymmetric coupling process demonstrated that selective ring opening occurred preferentially at the methylene C−O bond of the terminal epoxides5,32. The high selectivity of the asymmetric transformation reflected that CO2 molecules were also activated, providing favourable conditions for a fast reaction with epoxide by nucleophilic attack, avoiding the racemization of the epoxide through premature ring opening. It is postulated that these NH2 molecules in channels not only enhanced the reaction rate by increasing the concentration of CO2 substrate around its reactive centre but also increased the electron cloud density of activated CO2, enabling the cyclic carbonate ring formation35. In contrast to Ahn’s group reported that combination of Lewis acid and base give highly active for the CO2 cycloaddition to epoxide because of cooperative activation of epoxide by acid-base22, the Lewis acid catalytic zinc centres restricted within the ZnW-PYIs channels have the potential to interact synergistically with CO2 in view of spatial location matching of catalytic sites in MOFs, such that an intramolecularly cooperative catalysis is proposed to contribute to the high activity and excellent stereochemical control of the given reactions36.

The irreversible CO2-adsorption and desorption isotherms of ZnW−PYI1 may be attributed to the chemical adsorption onto the amine of NH2-BPY (Supplementary Fig. 13) (ref. 37). The infrared spectrum of activated ZnW−PYI1 in a vacuum and after the introduction of 1 bar of CO2 at room temperature clearly shows the loss of the NH stretching vibration peak at 3,126 cm−1, confirming that the CO2 was adsorbed and activated by NH2 groups in the channels of ZnW−PYI1 (Fig. 3c) (refs 38, 39). The Raman spectra of the MOF in a vacuum and after the introduction of 1 bar of CO2 showed peaks at 1,285 cm−1 (ref. 40), further supporting that CO2 molecules were adsorbed within the MOFs (Fig. 3d). Mechanistically, this reaction is based on a nucleophilic cocatalyst that activates the epoxide to form an alkoxide. This intermediate can then react with activated carbon dioxide to ultimately yield the cyclic carbonate.

One-pot asymmetric catalysis

Because chiral ZnW−PYIs demonstrated their ability as effective catalysts in the epoxidation of styrene and the coupling reaction, the one-pot synthesis was applicable to a range of different substrates. As shown in Table 1 (entries 9–11), by heating a reaction mixture of styrene, TBHP and CO2 with catalyst ZnW−PYI1 to 50 °C, the asymmetric epoxidation and the CO2 asymmetric coupling could be smoothly completed with a single workup stage. The target (R)-phenyl(ethylene carbonate) was obtained in 92% yield with 80% ee (Supplementary Fig. 24, Supplementary Table 9). The removal of ZnW−PYI1 by filtration after 48 h stopped the reaction, and the filtrate afforded nearly no additional conversion after stirring for another 48 h. These observations suggest that ZnW−PYI1 is a true heterogeneous catalyst. ZnW−PYI1 solids could be isolated from the reaction suspension by simple filtration. The catalysts could be reused at least three times with moderate loss of activity (from 92 to 88% yield) and with a slight decrease in selectivity (from 80 to 77% ee) (Supplementary Table 10). The index of PXRD patterns of the ZnW−PYI1 bulky sample filtered from the catalytic reaction revealed that the crystallinity was maintained. The ZnW−PYI2 solids exhibited similar catalytic activities but gave products with opposite chiralities in the asymmetric auto-tandem epoxidation/coupling of styrene.

Discussion

It was found that performing the reaction through a one-pot process could greatly shorten the reaction time to 4 days, and the configuration was maintained throughout both of the steps. It is clear from the crystal structures of the ZnW−PYIs that the smooth and stereoselective conversion of the olefins into the epoxide can be attributed to the hydrogen bonding interaction between the spatially matched organocatalyst PYI and the oxidation catalyst ZnW12O406− and to the potential π–π interaction between the benzene ring of styrene oxide and the imidazole ring of PYI. Because the CO2 molecules adsorbed in the channels of ZnW−PYI1 are activated by NH2 groups, the weak hydrogen bonding interactions between the chiral amine group N(12) and the amino group N(3) (interatomic separation of 3.79 Å) is believed to enforce the proximity between the activated CO2 and the terminal epoxide (Fig. 4). The well-matched positions and the suitable interactions provide a promising route for nucleophilic attack at the methylene C−O bond, ensuring chiral retention in the coupling process. The Lewis acid catalytic zinc centres restricted within the MOF channels have the potential to interact synergistically with CO2 such that the compatibility between the reaction intermediates and the synergy of the multiple catalytic cycles allow the auto-tandem reaction to proceed smoothly and efficiently36. Most importantly, the multi-catalytic sites with orderly distribution and spatial matching in the three-dimensional open framework provide favourable conditions for the auto-tandem reaction and avoid cross-interference.

The use of this catalyst can be extended to other styrene derivatives with comparable activity and asymmetric selectivity. In contrast to the smooth reaction of substrates 9–11, the one-pot catalytic reaction in the presence of cinnamaldehyde only gave 25% conversion under the same reaction conditions (Table 1, entry 12). It is suggested that the aldehyde group has the potential to interact with the NH2 group, inactivating these sites for the activation and concentration of CO2, which further substantiates the pivotal role of NH2 in the one-pot process.

We have developed an asymmetric auto-tandem epoxidation/cycloaddition catalytic reaction catalysed solely by chiral POMOFs, which proceeds in a highly enantioselective manner for the efficient conversion of light olefins into value-added enantiomerically pure cyclic carbonates in a one-pot procedure. The results demonstrated that asymmetric auto-tandem catalysis is an atom-economical and environmentally benign synthetic method for producing useful chiral compounds.

Future work will focus on design structurally diverse chiral POMOFs and optimizing such reactions. The structural simplicity of catalyst and the use of inexpensive and readily available chemical reagents render this approach highly promising for the development of practical homochiral materials for asymmetric catalytic reactions.

Methods

Reagents and Syntheses

All chemicals were of reagent grade quality obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. All epoxides were purchased from Acros and distilled under a nitrogen atmosphere from CaH2 prior to use. Carbon dioxide (99.995%) was purchased from Dalian Institute of Special Gases and used as received. All manipulations involving air- and/or water-sensitive compounds were carried out in glove box or under dry nitrogen using standard Schlenk techniques. L− and D−N-tert-butoxycarbonyl-2-(imidazole)-1-pyrrolidine (L− or D−BCIP) (ref. 41), 3-amino-4,4′-bipyridine (NH2-BPY) (ref. 42), and [(n-C4H9)4N]4 [W10O32] (ref. 43) were prepared according to the literature methods.

Elemental analyses

Elemental analyses of C, H and N were performed on a Vario EL III elemental analyser.

Inductively coupled plasma

W and Zn analyses were performed on a Jarrel-AshJ-A1100 spectrometer.

Fourier translation infrared spectrum (FT-IR)

FT-IR spectra were recorded as KBr pelletson JASCO FT/IR-430.

Powder X-ray diffractograms

PXRDs were obtained on a Riguku D/Max-2,400 X-ray diffractometer with Cu sealed tube (λ=1.54178 Å).

Circular dichroism spectrum

Circular dichroism spectra were measured on JASCO J-810 with solid KBr tabletting.

Laser-Raman spectrum

Raman spectroscopy (Lab Raman HR Evolution) measurements were performed using a solid state 785 nm laser. A laser power of 1–2.5% was used to avoid degradation of the sample under the laser beam during the Raman measurements.

Thermogravimetric analysis

Thermogravimetric analyses were performed on a Mettler-Toledo TGA/SDTA851 instrument and recorded under N2 or under air, upon 14 equilibration at 100 °C, followed by a ramp of 5 °C min−1 up to 800 °C.

Gas adsorption isotherms

Gas adsorption isotherms were collected using a Micromeritics 3Hex 128 instrument. As-synthesized crystals were thoroughly washed with anhydrous dichloromethane and dried under argon flow, approximately 100 mg of each sample was added into a pre-weighed sample analysis tube. The samples were degassed at 100 °C under vacuum for 24–48 h until the pressure change rate was no more than 3.5 mTorr min−1. Ultra high purity (UHP) grade N2 and CO2 gas adsorbates (99.999 %) were used in this study.

Nuclear magnetic resonance

1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a Varian INOVA-400 MHz type (1H, 400 MHz; 13C, 400 MHz) spectrometer. Their peak frequencies were referenced versus an internal standard (tetramethylsilane (TMS)) shifts at 0 p.p.m. for 1H NMR and against the solvent, chloroform-D at 77.0 p.p.m. for 13C NMR, respectively.

High-performance liquid chromatography

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis was performed on Agilent 1,150 using a ChiralPAk OD−H column or AD−H column purchased from Daicel Chemical Industries, Ltd.

Crystallography

Data of POMOFs ZnW−PYIs were collected on a Bruker SMART APEX CCD diffractometer with graphite-monochromated Mo-Kα (λ=0.71073 Å) using the SMART and SAINT programs44,45. Routine Lorentz polarization and Multi-scan absorption correction were applied to intensity data. Their structures were determined and the heavy atoms were found by direct methods using the SHELXTL-97 program package46. The remaining atoms were found from successive full-matrix least-squares refinements on F2 and Fourier syntheses. Not all the non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. Hydrogen atoms within the ligand backbones were fixed geometrically at their positions and allowed to ride on the parent atoms. Crystallographic data for ZnW−PYIs are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Synthesis of ZnW−PYI1

A mixture of [(n-C4H9)4N]4[W10O32] (66.4 mg, 0.02 mmol), Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (60.0 mg, 0.20 mmol), NH2-BPY (10.3 mg, 0.06 mmol) and L−BCIP (7.5 mg, 0.03 mmol) in mixed water (4.0 ml) and acetonitrile (2.0 ml) was stirred and its pH value was adjusted to 4.3 with 1 mol l−1 acetic acid (HAc). The resulting suspension was sealed in a 25 ml Teflon-lined reactor and kept at 130 °C for 3 days. After cooling the autoclave to room temperature, yellow rod-like single crystals were separated, washed with water and air-dried. (Yield: calculated (calcd) 68% based on [(n-C4H9)4N]4[W10O32]). Elemental analyses and inductively coupled plasma calcd (%) for C40H54N14O41W12Zn3: C 12.68, H 1.44, N 5.18, Zn5.18, W 58.22; Found: C 12.64, H 1.41, N 5.20, Zn5.22, W 58.24 for ZnW−PYI1. IR (KBr): 3,440 (s), 3,123(w), 1,619(s), 1,532(s), 1,247 (s), 1,103(w), 938(s), 872(s), 756(versus) per cm.

Synthesis of ZnW−PYI2

The preparation of ZnW−PYI2 was similar to that of ZnW−PYI1, except that D−BCIP (50.0 mg, 0.2 mmol) replaced L−BCIP. (Yield: ca. 68% based on [(n-C4H9)4N]4[W10O32]). Elemental analyses and inductively coupled plasma calcd (%) for C40H54N14O41W12Zn3: C 12.68, H 1.44, N 5.18, Zn5.18, W 58.22; Found: C 12.64, H 1.42, N 5.17, Zn 5.20, W 58.25 for ZnW−PYI2. IR (KBr): 3,443 (s), 3,124(w), 1,618(s), 1,531(s), 1,248 (s), 1,104(w), 939(s), 873(s), 757(versus) per cm.

Typical one-pot procedure for asymmetric catalysis

Catalyst (0.01 mmol), TBABr (0.1 mmol), TBHP (20 mmol) and styrene (10 mmol) was added to a Schlenk flask (50 ml) equipped with a three-way stopcock. Then CO2 was charged into the autoclave, and the pressure (0.5 MPa) was kept constant during the reaction. The autoclave was put into a bath and heated to the 50 °C. After the expiration of the desired time, the excess gases were vented. The remaining mixture was degassed and fractionally distilled under reduced pressure or purified by column chromatography on silica gel to obtain the cyclic carbonate.

Additional information

Accession codes: The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1063826–1063827. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

How to cite this article: Han, Q. et al. Polyoxometalate-based homochiral metal-organic frameworks for tandem asymmetric transformation of cyclic carbonates from olefins. Nat. Commun. 6:10007 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10007 (2015).

References

Raman, S. K., Brulé, E., Tschan, M. J. L. & Thomas, C. M. Tandem catalysis: a new approach to polypeptides and cyclic carbonates. Chem. Commun. 50, 13773–13776 (2014).

Zhu, Y. G., Wang, Q., Cornwall, R. G. & Shi, Y. A. Metal-catalyzed asymmetric sulfoxidation, epoxidation and hydroxylation by hydrogen peroxide. Chem. Rev. 114, 8199–8256 (2014).

Katsuki, T. & Sharpless, K. B. The first practical method for asymmetric epoxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 5974–5976 (1980).

Zhang, S. L., Huang, Y. Z., Jing, H. W., Yao, W. X. & Yan, P. Chiral ionic liquids improved the asymmetric cycloaddition of CO2 to epoxides. Green Chem. 11, 935–938 (2009).

Ren, W. M., Liu, Y. & Lu, X. B. Bifunctional Aluminum Catalyst for CO2 Fixation: Regioselective ring opening of three-membered heterocyclic compounds. J. Org. Chem. 79, 9771–9777 (2014).

Sun, J. S. et al. Direct synthetic processes for cyclic carbonates from olefins and CO2 . Catal. Surv. Asia 15, 49–54 (2011).

Abou-Shehada, S. & Williams, J. M. Separated tandem catalysis, It’s about time.. Nat. Chem. 6, 12–13 (2014).

Li, L. & Herzon, S. B. Temporal separation of catalytic activities allows anti-Markovnikov reductive functionalization of terminal alkynes. Nat. Chem. 6, 22–27 (2014).

Grondal, C., Jeanty, M. & Enders, D. Organocatalytic cascade reactions as a new tool in total synthesis. Nat. Chem. 2, 167–178 (2010).

Yoon, M., Srirambalaji, R. & Kim, K. Homochiral metal-organic frameworks for asymmetric heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 112, 1196–1231 (2012).

Cook, T. R., Zheng, Y. R. & Stang, P. J. Metal−organic frameworks and self-assembled supramolecular coordination complexes: comparing and contrasting the design, synthesis, and functionality of metal−organic materials. Chem. Rev. 113, 734–777 (2013).

An, J. et al. Metal-adeninate vertices for the construction of an exceptionally porous metal-organic framework. Nat. Commun 3, 604 (2012).

Bromberg, L., Su, X. & Hatton, T. A. Heteropolyacid-functionalized aluminum 2-amino-terephtha-late metal-organic frameworks as reactive aldehyde sorbents and catalysts. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 5468–5477 (2013).

Zhang, Z. M. et al. Photosensitizing metal−organic framework enabling visible-light driven proton reduction by a Wells−Dawson-type polyoxometalate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 3197–3200 (2015).

Wu, P. Y. et al. Photoactive chiral metal−organic frameworks for light-driven asymmetric α-alkylation of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 14991–14999 (2012).

Mizuno, N. & Kamata, K. Catalytic oxidation of hydrocarbons with hydrogen peroxide by vanadium-based polyoxometalates. Coord. Chem. Rev. 255, 2358–2370 (2011).

Du, D. Y., Qin, J. S., Li, S. L., Su, Z. M. & Lan, Y. Q. Recent advances in porous polyoxometalatebased metal–organic framework materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 4615–4632 (2014).

Hua, Z. K., Fu, X. K., Li, Y. D. & Tu, X. B. Highly efficient and excellent reusable catalysts of molybdenum(VI) complexes grafted on ZPS-PVPA for epoxidation of olefins with tert-BuOOH. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 25, 128–132 (2011).

Han, Q. X. et al. Engineering chiral polyoxometalate hybrid metal−organic frameworks for asymmetric dihydroxylation of olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10186–10189 (2013).

Kim, J., Kim, S. N., Jang, H. G., Seo, G. & Ahn, W. S. CO2 cycloaddition of styrene oxide over MOF catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 453, 175–180 (2013).

Feng, D. W. et al. Construction of ultrastable porphyrin Zr metal−organic frameworks through linker elimination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 17105–17110 (2013).

Gao, W. Y. et al. Crystal engineering of an nbo topology metal–organic framework for chemical fixation of CO2 under ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 2615–2619 (2014).

Beyzavi, M. H. et al. A Hafnium-based metal−organic framework as an efficient and multifunctional catalyst for facile CO2 fixation and regioselective and enantioretentive epoxide activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15861–15864 (2014).

Spek, A. L. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 7–13 (2003).

Mizuno, N., Yamaguchi, K. & Kamata, K. Epoxidation of olefins with hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by polyoxometalates. Coord. Chem. Rev. 249, 1944–1956 (2005).

Duncan, D. C., Chambers, R. C., Hecht, E. & Hill, C. L. Mechanism and dynamics in the H3[PW12O40] catalyzed selective epoxidation of terminal olefins by H2O2. Formation, reactivity, and stability of {PO4[WO(O2)2]4}3−. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 681–691 (1995).

Taylor, M. S. & Jacobsen, E. N. Asymmetric catalysis by chiral hydrogen-bond donors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 1520–1543 (2006).

Melchiorre, P., Marigo, M., Carlone, A. & Bartoli, G. Asymmetric aminocatalysis—gold rush in organicchemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 6138–6171 (2008).

Couck, S. et al. An amine-functionalized MIL-53 metal−organic framework with large separation power for CO2 and CH4 . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6326–6327 (2009).

Vaidhyanathan, R. Direct observation and quantification of CO2 binding within an amine-functionalized nanoporous solid. Science 330, 650–653 (2010).

Pham, T. et al. Understanding hydrogen sorption in a metal−organic framework with open-metal sites and amide functional groups. J. Phys. Chem C117, 9340–9354 (2013).

Chisholm, M. H. & Zhou, Z. P. Concerning the mechanism of the ring opening of propylene oxide in the copolymerization of propylene oxide and carbon dioxide to give poly(propylene carbonate). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 11030–11039 (2004).

Ishimoto, R., Kamata, K. & Mizuno, N. A. Highly active protonated tetranuclear peroxotungstate for oxidation with hydrogen peroxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 4662–4665 (2012).

Aggrawal, V. K., Lopin, C. & Dandrinelli, F. New insights in the mechanism of amine catalyzed epoxidation: dual role of protonated ammonium salts as both phase transfer catalysts and activators of oxone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7596–7601 (2003).

Yoshizawa, M., Tamura, M. & Fujita, M. Diels-alder in aqueous molecular hosts: unusual regioselectivity and efficient catalysis. Science 312, 251–254 (2006).

Liao, P. Q. et al. Strong and dynamic CO2 sorption in a flexible porous framework possessing guest chelating claws. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17380–17383 (2012).

Gassensmith, J. J. et al. Strong and reversible binding of carbon dioxide in a green metal–organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 15312–15315 (2011).

Srikanth, C. S. & Chuang, S. S. C. Spectroscopic investigation into oxidative degradation of silica-supported amine sorbents for CO2 capture. Chem. Sus. Chem. 5, 1435–1442 (2012).

McDonald, T. M. et al. Capture of carbon dioxide from air and flue gas in the alkylamine-appended metal–organic framework mmen-Mg2(dobpdc). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7056–7065 (2012).

Nijem, N. et al. Understanding the preferential adsorption of CO2 over N2 in a flexible metal-organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 12849–12857 (2011).

Luo, S. Z. et al. Functionalized chiral ionic liquids as highly efficient asymmetric organocatalysts for Michael addition to nitroolefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 3093–3097 (2006).

Katritzky, A. R. et al. Preparation of nitropyridines by nitration of pyridines with nitric acid. Org. Biomol. Chem. 3, 538–541 (2005).

Ginsberg, A. P. Inorganic syntheses, Copyright © 1990, By. Inorg. Synth., Inc 27, 81–82 (1990).

SMART, Data collection software (version 5.629) (Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, WI, 2003).

SAINT, Data reduction software (version 6.45) (Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, WI, 2003).

Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXTL97, Program for Crystal Structure Solution (University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 1997).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21421005, 21231003 and U1304201), the Basic Research Program of China (2013CB733700), and the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT1213).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.X.H., C.H. and C.Y.D. conceived and designed the experiments. Q.X.H., B.Q. and W.M.R. performed the experiments. C.H., J.Y.N. and C.Y.D. contributed materials and analysis tools. Q.X.H., C.H. and C.Y.D. co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-24, Supplementary Tables 1-10, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 4574 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

Crystal data of complex Zn-PYI1-L (CIF 42 kb)

Supplementary Data 2

Crystal data of complex Zn-PYI2-D (CIF 40 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Q., Qi, B., Ren, W. et al. Polyoxometalate-based homochiral metal-organic frameworks for tandem asymmetric transformation of cyclic carbonates from olefins. Nat Commun 6, 10007 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10007

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10007

This article is cited by

-

AuPd Alloys and Chiral Proline Dual-Functionalized NH2-UiO-66 Catalysts for Tandem Oxidation/Asymmetric Aldol Reactions

Catalysis Letters (2023)

-

Design and synthesis of polyoxovanadate-based framework for efficient dye degradation

Tungsten (2023)

-

Pd(II)-Metalated and l-Proline-Decorated Multivariate UiO-67 as Bifunctional Catalyst for Asymmetric Sequential Reactions

Catalysis Letters (2022)

-

Application of hierarchically porous metal-organic frameworks in heterogeneous catalysis: A review

Science China Materials (2022)

-

Ionic Liquid Supported on DFNS Nanoparticles Catalyst in Synthesis of Cyclic Carbonates by Oxidative Carboxylation

Catalysis Letters (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.