Abstract

The onset of psychosis is the consequence of complex interactions between genetic vulnerability to psychosis and response to environmental and/or maturational changes. Epigenetics is hypothesized to mediate the interplay between genes and environment leading to the onset of psychosis. We believe we performed the first longitudinal prospective study of genomic DNA methylation during psychotic transition in help-seeking young individuals referred to a specialized outpatient unit for early detection of psychosis and enrolled in a 1-year follow-up. We used Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip array after bisulfite conversion and analyzed longitudinal variations in methylation at 411 947 cytosine–phosphate–guanine (CpG) sites. Conversion to psychosis was associated with specific methylation changes. Changes in DNA methylation were significantly different between converters and non-converters in two regions: one located in 1q21.1 and a cluster of six CpG located in GSTM5 gene promoter. Methylation data were confirmed by pyrosequencing in the same population. The 100 top CpGs associated with conversion to psychosis were subjected to exploratory analyses regarding the related gene networks and their capacity to distinguish between converters and non-converters. Cluster analysis showed that the top CpG sites correctly distinguished between converters and non-converters. In this first study of methylation during conversion to psychosis, we found that alterations preferentially occurred in gene promoters and pathways relevant for psychosis, including oxidative stress regulation, axon guidance and inflammatory pathways. Although independent replications are warranted to reach definitive conclusions, these results already support that longitudinal variations in DNA methylation may reflect the biological mechanisms that precipitate some prodromal individuals into full-blown psychosis, under the influence of environmental factors and maturational processes at adolescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The identification of clinical ultra-high-risk state for psychosis (hereinafter UHR; also known as the ‘at-risk mental state’) has been a relatively recent development in the field of psychiatry, and it has provided a means to capture the prepsychotic phase and to describe individuals with prodromal symptoms that may transition into psychosis and schizophrenia.1 Operational criteria for UHR have been proposed,2 based on specific comprehensive interviews. In individuals reaching these criteria, the conversion rate of individuals at UHR to full-blown psychosis is 30–40% in the following 24 to 36 months.3 Nevertheless, the populations reaching UHR criteria remain heterogeneous with the possibility of several outcomes, including symptomatic regression or development of non-psychotic disorders, rather than psychosis, which underscores the need for more predictive markers. Deciphering the biological mechanisms underlying the onset of psychosis requires longitudinal measures in help-seeking patients that includes characterization of their outcomes.

Understanding the different pathophysiological pathways leading to conversion to psychosis is a major issue of the field. The literature about conversion to psychosis, however, is still maturing and molecular findings remain limited. From the molecular point of view, conversion to psychosis is viewed as the complex interaction between biological vulnerability and exposure to many potentially harmful environmental risk factors.4 This is in line with the overall gene × environment interaction hypothesis in schizophrenia, whereby the influence of the environment is thought to induce epigenetic changes.5 Until now, however, the epigenetic signature of conversion to psychosis has not been studied. Epigenetic regulation involves dynamic processes that have a role in controlling gene expression levels, among which histone posttranscriptional modifications and methylation of genes on cytosine–phosphate–guanine (CpG) dinucleotides have been the main focus of the research. New methylomic technologies enable investigation of CpG methylation sites at the genomic scale. A large methylome-wide-association study recently compared patients with established schizophrenia to controls and found 139 differentially methylated CpGs, including FAM63B and RELN.6

To our knowledge, no previous study has considered pangenomic methylation longitudinal changes accompanying conversion to psychosis. In this study, we explored blood methylation biomarkers associated with conversion to psychosis in a methylomic association study involving young help-seeking individuals who were enrolled in a longitudinal follow-up program. We were able to detect significant differentially methylated regions (DMRs). We conducted an original exploration of multiple CpG sites followed by pathway and cluster analyses of the top methylation changes. Then we confirmed the top findings using pyrosequencing.

Materials and methods

Population

Our study was approved by the institutional ethics committee ‘Comité de protection des personnes, Ile-de-France III, Paris, France’, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Help-seeking individuals (16–30 years) consecutively referred to the Adolescent and Young Adults Assessment Centre (Service Hospitalo-Universitaire, Hôpital Sainte-Anne, Paris, France) between 2009 and 2013 were enrolled in the ICAAR collaborative study promoted by Sainte-Anne Hospital as already described.7 Inclusion criteria were alterations in global functioning (Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale score <70) during the past year that were associated with psychiatric symptoms and/or subjective cognitive complaints. Exclusion criteria included manifest symptoms of psychosis, pervasive developmental or bipolar disorders and individuals with other established diagnoses, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (fulfilling Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria). Other exclusion criteria were: current antipsychotic treatment (>100 mg Chlorpromazine equivalent) for >12 weeks, psychoactive substance dependence or abuse during the previous year and/or >5 years, serious or non-stabilized somatic and neurological disorders head injury and intelligent quotient <70. All subjects were examined with the Comprehensive Assessment for at-risk mental state (CAARMS,8 in its translated version9) by specifically trained psychiatrists followed by a consensus meeting for best-estimate diagnoses. Individuals fulfilling the criteria for at-risk mental state were characterized as UHR; conversion to psychosis was characterized using the CAARMS-defined psychosis onset threshold (that is, supra-threshold psychotic symptoms—thought content, perceptual abnormalities and/or disorganized speech—present for >1 week) (see Supplementary Table S1) was used. All subjects excepted those above the psychosis threshold at baseline (M0) were included in the longitudinal follow-up, whether or not they were UHR. Subjects who reach the psychosis threshold during follow-up were classified as converters. The clinical assessment and blood sample collection were repeated after 6 and 12 months or after psychosis onset. In this study, 39 individuals were included and enrolled in the longitudinal follow-up, among whom 14 subsequently developed full-blown psychosis (converters), whereas 25 did not (non-converters). There were no significant differences between these two groups at baseline in sex ratio, age, follow-up duration, body mass index, substance abuse or psychotropic treatment introduction (Table 1). Of the 25 non-converters individuals, 13 were UHR and 12 were non-UHR at baseline. Non-UHR individuals had variable subthreshold symptoms (anxiety and depressive symptoms) without reaching criteria of a fully characterized disorder.

Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation

Preparation

For each individual, genomic DNA (500 ng) was extracted from whole blood and treated with sodium bisulfite using the EZ-96DNA Methylation KIT (Catalog No D5004, Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s standard protocol. Methylation was measured at M0 and after the longitudinal follow-up (MF) by the same technique at the same time for all samples. Genome-wide DNA methylation was assessed using Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), which interrogates the DNA methylation profile of >485 000 CpG loci across the genome at single-nucleotide resolution.

Data preprocessing and clean up

Illumina GenomeStudio software (Illumina) was used to extract signal intensities for each probe. All computations and statistical analyses were performed within the R statistical analysis environment (http://www.r-project.org), and all scripts are available on request from the authors. R packages methylumi and wateRmelon were used for data quality check and normalization. Steps used for data clean-up procedure and normalization comprised gender check between phenotype file and methylation data set and evaluation of single-nucleotide polymorphism genotypes concordance between the two samples from the same individuals. Subsequent clean-up steps comprised flagging and removing individuals with no result or gender discrepancies or discordant genotypes, samples with ⩾1% of sites with a detection P-value ⩾0.05, probes with beadcount <3 in ⩾5% of samples, probes with ⩾1% of samples with a detection P-value ⩾0.05. Additionally, probes on chromosomes X and Y, single-nucleotide polymorphism probes, probes with a single-nucleotide polymorphism at the CpG site and non-specific probes that map to more than one location in the genome were removed.10 The initial methylation data file includes 485 577 probes, and after normalization and data clean up, 411 947 probes were kept for the final analysis (Supplementary Table S2). R Minfi package was used for supplementary quality control (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2), and no sample was removed. No batch effect was detected (according to Combat R Package using SVA function). Cellular populations were estimated by EstimateCellCounts function (Minfi package).

Association analysis

Global methylation change was investigated by computing the difference between mean methylation changes for all probes in each individual and comparing converters to non-converters. DMRs were investigated using Minfi package in R (script available upon request). In summary, time and group were used as factors in a linear model adjusted by cellular populations with a paired design. DMR analysis was performed using bumphunter function (bootstrap with 1000 permutations and a methylation differential cutoff of 10). Significance was established for fwer correction <0.1.

Multi-CpG analysis

Because methylation changes could occur in different CpG from various genes converging to the same pathways, we developed a new pipeline to examine methylation longitudinal changes at each CpG site. Linear model with moderated t-statistic was used.11 Statistical analysis was performed with R script (using R Limma Package) testing the following model: Difference in methylation (MF−M0)=psychosis (converters vs non-converters)+gender. The multiple-testing-adjusted significance threshold for probe-wise analysis was established at P=1.2x10−7 (0.05/411 947 analyzed probes). QQ-plot is displayed in Supplementary Figure S3. Top results of this analysis were pasted in ConsensusPathDB12 and Enrichr13 and an overrepresentation analysis based on Reactome, wikipathways and KEGG database was used with a hypergeometric correction to explore whether our top findings are linked to specific biological pathways more than expected by chance. Clustering analysis of the same top results was performed using the MultiExperimentViewer software (version 4.9.0).14 Methylation differential rates were inputted and normalized by genes. For hierarchical clustering, we used ‘K-Nearest Neighbors imputation engine’ (number of neighbors=10) and ‘Average linkage clustering’ using Pearson correlation and asked to construct a gene/sample tree.

Confirmation by pyrosequencing

Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip is a current and reliable array to detect CpG methylation.15 However, we propose to compare some of our findings using a technical reference based on pyrosequencing.16 After bisulfite conversion by EpiTect Plus Bisulfite Kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and DNA purification on column, non-methylation specific PCR were achieved using Platinium Taq DNA polymerase kit (Invitrogen—Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). MAEL promoter was used as positive control for the bisulfite treatment17 in bisulfited and non-bisulfited samples (Supplementary Figures S4 and S5). Two findings were assessed: we chosen to confirm one specific CpG selected from the top results of multi-CpGs analysis (CpG located in CHL1 gene) and one significant DMR in GSTM5 (the only one significant DMR including a promoter) identified by the Minfi package. Primers were designed by the PyroMark Assay design Software 2.0 (Qiagen), and technical conditions for PCR are shown in Supplementary Table S3; examples of results are shown in Supplementary Figure S6. Biotinylated primers were used to keep the single DNA strand for pyrosequencing. Pyrosequencing was performed using PyroMark Q24 (Qiagen) according the manufacturer’s instructions, and data about methylation in each CpG were extracted and analyzed using the PyroMark Q24 2.0.6.20 software (Qiagen).

Results

Longitudinal global methylation change in converters vs non-converters

No significant changes in global methylation were associated with the occurrence of conversion to psychosis (P=0.41).

Longitudinal methylation changes at specific regions in converters vs non-converters

After paired analysis, we identified two significant DMRs (fwer<0.1), including at least two CpGs. The region including HLA-DQ and HLA-DRB (chromosome 6 [32523136; 32633163]) was excluded because of frequent recurrence of this finding by the Minfi package, suggesting spurious results due to the algorithm (according to its authors). The two DMRs were identified in chromosome 1: first region located in [146549909;146550467] corresponding to 1q21.1 and second region in [110254662; 110254835] including the GSTM5 gene promoter. Significant and suggestive results are shown in Table 2. These DMRs are quite stable across time, which could suggest that differences in methylation pattern in these regions could predate conversion to psychosis. We conducted a transversal exploratory analysis comparing subjects at M0 and subjects at MF (Supplementary Table S4). Fifteen DMRs were concordant before and after conversion but three appeared different across groups after transition only. Interestingly, two of these three DMRs were in 22q11 region and are located near GSTT1 and GSTP1, two genes from the same family as GSTM5.

Longitudinal methylation changes in CpG sites between converters and non-converters

We tested whether changes of methylation in different CpG sites located in distinct genes were associated with psychotic transition. Longitudinal methylation changes at specific CpGs associated with conversion to psychosis are shown in a Manhattan plot (Supplementary Figure S7, see also the top 100 CpGs in Supplementary Table S5). None of the individual CpG changes alone reached significance at a genome-wide level. The best associated CpG sites with conversion to psychosis (top 100 CpGs) were kept for biological pathways analysis and revealed two networks implicating eight genes: an axon guidance pathway and the interleukin (IL)-17 signaling pathway (Table 3).

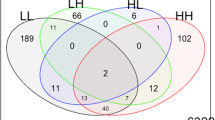

We performed a cluster analysis of individual data from the top 100 CpGs. Hierarchical clustering of the methylation changes of these top 100 CpGs successfully discriminated between the converters and non-converters (Figure 1). We examined whether the prescription of psychotropic treatment in 10 individuals (6 converters and 4 non-converters) during follow-up could account for the observed methylomic changes. We tested whether the same top CpGs sites display significant methylation modifications in patients in whom medication (antipsychotics or valproate) is initiated compared with those who have no treatment changes. Only two DNA methylation profiles showed a significant difference in methylation change in relation to medication initiation (cg 09270366 located in the inositol-polyphosphate 5-phosphatase gene (nominal P=0.0019) and cg 05768558 located in the Lin-28 homolog A gene (nominal P=0.03)).

Multi-CpGs clustered and classified as converters (in orange) and non-converters (in blue). CpG, cytosine–phosphate–guanine.

Confirmation of significant results by pyrosequencing

We performed pyrosequencing of CHL1 gene (ch3: 240139) in the 78 samples. Pyrosequencing results were significantly correlated with Meth450K beadchip results (P=0.005; Spearman’s rho=0.32).

We also performed pyrosequencing of GSTM5. It shows large and significant differences between converters and non-converters regardless of the time of assessment (Figure 2; Supplementary Figure S8), with converters showing hypermethylation of GSTM5 promoter. Whereas bio-informatical analyses identified a cluster of six differentially methylated CpG, pyrosequencing further revealed that four additional CpGs located in the promoter, not targeted by the Meth450 beadchip, showed significant methylation change.

Mean of methylation in each CpG (cytosine–phosphate–guanine) located in the GSTM5 promoter. Full line=non-converter; dash line=converter. Mann-Whitney test: *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation profiles in individuals during conversion to psychosis and one of its strength is the longitudinal design. We observed that conversion to psychosis was not associated with a global change in methylation and there was no individual CpG significantly associated with psychotic transition, in line with previous findings showing that one individual CpG is rarely associated with one disease. By contrast, we found that conversion to psychosis was associated with specific methylation changes in genes involved in axon guidance, as well as genes of the IL-17 pathway and the glutathione-S-transferase family.

Both genome-wide and confirmatory experiments suggested that methylation changes, especially in the 1q21.1 region and in the promoter of the GSTM5 gene, were associated with psychosis onset. Deletion of 1q21.1 region has previously been associated with schizophrenia.18 This deletion classically encompasses several genes, including HYDIN2 associated with macrocephaly and autism, suggesting an alteration of neurodevelopment.19 GSTM5 is a member of glutathione-S-transferase family and is implicated in the synthesis of glutathione and protection against oxidative stress, which seems to be part of the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.20 Oxidative stress has recurrently been suggested to be related to different stages of schizophrenic illness.21 GSTM5 is selectively expressed in the brain22 and is the most commonly expressed member of its gene family in this tissue.23 Its involvement in dopamine metabolism has also been suggested.24 Moreover, its expression has been shown to be decreased in the prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia.25 Furthermore, GSTM5 levels displayed an inverse correlation with promoter DNA methylation in brain tissue, supporting the idea that GSTM5 CpG methylation status controls gene expression.26 Interestingly, our exploratory approach provided evidence that two other genes of GST family might be differentially methylated after conversion to psychosis: the GSTT1 and GSTP1 regions were hypomethylated and hypermethylated in converters, respectively, without differences between the groups at baseline. These findings suggest the possibility that conversion to psychosis may depend on the specific control of oxidative metabolism and balance between these genes.

Cluster analysis showed that a subset of top CpGs with the most significant changes in methylation during psychotic conversion correctly classified converters and non-converters, with no influence of medication initiation. Pathway analysis revealed that these top epigenetic changes were overrepresented in certain biological pathways, including an axon guidance pathway and the IL-17 pathway. The axon guidance pathway included the neural cell adhesion protein CHL1 gene (cell adhesion molecule L1-like), which codes for the L1CAM2 protein. The L1 family encompasses immunoglobulin-class recognition proteins that promote axon growth and migration in developing neurons.27 In preclinical models, a deficit of CHL1 in adult mice impairs working memory,28 social behavior and synaptic transmission.29 Genetic variants in the CHL1 gene have been found to be associated with schizophrenia.30, 31, 32 Neuropilin1 (NRP1), also included in this pathway, acts as a receptor that mediates axonal inhibition or repulsion. Neuropilin1 colocalizes with L1CAM2 in the thalamic axons33 and in immature neurons;34 they interact together in growth cone collapse, a process important for developing axons.33 EFNA3, the third gene found in our analysis, is highly expressed in mature neurons, suggesting that an imbalance in expression exists during cerebral maturation between CHL1, NRP1 and EFNA3. EFNA3 encodes ephrin-A3, which is a critical protein for the regulation of synaptic function and plasticity in astrocytes.35 The second signaling pathway, namely the IL-17 pathway, is involved in the regulation of inflammatory factors and in the immune response to bacterial pathogens. Variations in genes involved in immune response is a recurrent finding in association studies of schizophrenia.36, 37 A recent proteomic study identified ILs as potential diagnostic biomarkers in the onset of psychosis.38 Differences in the level of several inflammatory cytokine were found in individuals with schizophrenia compared with healthy controls, with a positive correlation between the levels of cytokines in the IL-17 pathway and scores on the Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale.39 This pathway includes AKT1, a serine–threonine kinase and a critical mediator of growth-factor-induced neuronal survival in the developing nervous system.40 Decreased AKT1 protein levels and phosphorylation activity were documented in the lymphocytes and brains of individuals with schizophrenia.41, 42 In addition, it was reported that AKT1 genetic variants were associated with schizophrenia, in relation to cannabis use.43

The genome-wide approach, without predefinite candidate regions, was crucial for identifying new relevant regions that undergo differential methylation or demethylation changes in converters and non-converters across the baseline and follow-up intervals. Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip interrogates about 485 000 CpG sites after bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines. This design is valuable as it does not require the selection of a small number of ‘candidate’ genes or methylation sites. Further, we compared these results with a reference method based on pyrosequencing; the correlation was significant between the beadchip and pyrosequencing as reported in the literature.15 Pyrosequencing identified additional differentially methylated neighboring CpGs in GSTM5 promoter (four additional CpGs not initially interrogated by the Meth450K array), further strengthening the methylomic results.

The genes identified in our study had not been previously reported in methylomic studies of schizophrenia.6, 44, 45 These differences may be due to the fact that, in addition to methodological issues (notably differences in methylome coverage), we employed an original methodology based on longitudinal variation in methylation levels, which cannot easily be compared with methylation measurements from single time point studies in subjects with established schizophrenia. Moreover, in two of the three published studies, patients were aged 30 years older, on average, than our participants and methylation changes with age.46

The present work was conducted in adolescents and young adults consecutively referred to a clinic specialized for early detection of psychosis and enrolled in a longitudinal follow-up program. We did not find any differences in environmental exposure between those who converted to psychosis and those who did not, and the methylation changes associated with conversion to psychosis were not related to the initiation of medication. The observed modifications in methylation are thus more likely to be linked to psychosis conversion than to medication initiation or other environmental changes. Even if the sample sizes were sufficient to identify some significant DMRs, larger samples are needed to identify other DMRs. Another issue to identify DMRs is the molecular and clinical heterogeneity between individuals, a well-known issue in the genetics of psychosis.47 The sample size could not allow us to overpass this heterogeneity.

The amplitude of methylation changes in DMR was similar to that found in previous studies in peripheral tissues comparing individuals with psychiatric disorders and healthy controls44, 48 and seems to be biologically relevant (>10%). However, our observations suggest that individual methylation levels are relatively stable. The extent to which these findings (which were based on peripheral markers) reflect methylation processes in the brain cannot be definitively concluded. Mounting evidence favors a relative concordance between methylation profiles in the brain and blood peripheral cells,49, 50 although the amplitude of peripheral methylation levels might be lower for the equivalent loci in central tissues.45 Blood and brain convergence has been investigated by the beadchip suggesting that subset of peripheral data may proxy methylation status of brain tissue.51 Within-subjects design, as we performed here, are recommended.

Our study has several strengths: We conducted a long-term prospective follow-up in both individuals at UHR for psychosis and non-UHR subjects. We used rapidly frozen samples enabling the study of a larger number of methylation sites (even more labile ones). We report longitudinal variations in methylation, which are more suitable for reflecting dynamic epigenetic processes compared with single time point analyses. We used a genome-wide strategy rather than limited candidate genes strategy. We used newly developed pathway and clustering analyses to investigate the functional relevance of top CpG methylation sites. Several issues need to be addressed in future studies, however, including the problem of clinical heterogeneity and the possible influence of a larger number of environmental factors (for example, early stressful events). It will also be important to make direct measures of maturational changes (for example, using brain imaging) and to examine interactions between CpG methylation and other mechanisms of epigenetic regulation. Finally, inter-individual heterogeneity raises a yet-to-be-investigated hypothesis that private epimutations might be involved in the conversion to psychosis.

In conclusion, we found that the conversion to psychosis in young help seekers is accompanied by epigenetic changes in genes involved in relevant genes and pathways. We also identified possible candidate mechanisms, including alterations in oxidative stress regulation, axon guidance and in inflammatory pathways. These candidate genes could represent multiple theaters for the disruption in homeostasis that accompanies the emergence of full-blown psychosis. At this point, it is unknown whether the observed methylation changes have a causal role in the processes leading to psychosis or whether they are simply reflective of psychosis onset. These new observations shed light on the biological processes underlying the interactions between early vulnerability, late environmental response and maturational processes at adolescence that can precipitate some UHR individuals into full-blown psychosis. This exploratory study is a first step toward the identification of epigenetic changes accompanying the onset of psychosis and opens new perspectives for early intervention and prevention in psychosis. Replications in larger and/or independent samples are warranted to reach definitive conclusions. Future developments should also investigate the functional impact of these methylation changes.

References

Yung AR, McGorry PD . The initial prodrome in psychosis: descriptive and qualitative aspects. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1996; 30: 587–599.

Correll CU, Hauser M, Auther AM, Cornblatt BA . Research in people with psychosis risk syndrome: a review of the current evidence and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010; 51: 390–431.

Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, Borgwardt S, Kempton MJ, Valmaggia L et al. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69: 220–229.

European Network of National Networks studying Gene-Environment Interactions in Schizophrenia (EU-GEI), van Os J, Rutten BP, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Viechtbauer W et al. Identifying gene-environment interactions in schizophrenia: contemporary challenges for integrated, large-scale investigations. Schizophr Bull 2014; 40: 729–736.

Rivollier F, Lotersztajn L, Chaumette B, Krebs M-O, Kebir O . Epigenetics of schizophrenia: a review. Encephale 2014; 40: 380–386.

Aberg KA, McClay JL, Nerella S, Clark S, Kumar G, Chen W et al. Methylome-wide association study of schizophrenia: identifying blood biomarker signatures of environmental insults. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71: 255–264.

Chaumette B, Kebir O, Mam Lam Fook C, Morvan Y, Bourgin J, Godsil BP . Salivary cortisol in early psychosis: new findings and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015; 63: 262–270.

Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Kelly D, Dell’Olio M et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2005; 39: 964–971.

Krebs M-O, Magaud E, Willard D, Elkhazen C, Chauchot F, Gut A et al. Assessment of mental states at risk of psychotic transition: Validation of the French version of the CAARMS. L’Encephale 2014; 40: 447–456.

Price ME, Cotton AM, Lam LL, Farré P, Emberly E, Brown CJ et al. Additional annotation enhances potential for biologically-relevant analysis of the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip array. Epigenetics Chromatin 2013; 6: 4.

Diboun I, Wernisch L, Orengo CA, Koltzenburg M . Microarray analysis after RNA amplification can detect pronounced differences in gene expression using limma. BMC Genomics 2006; 7: 252.

Kamburov A, Stelzl U, Lehrach H, Herwig R . The ConsensusPathDB interaction database: 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41: D793–D800.

Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Duan Q, Wang Z, Meirelles GV et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics 2013; 14: 128.

Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. BioTechniques 2003; 34: 374–378.

Roessler J, Ammerpohl O, Gutwein J, Hasemeier B, Anwar SL, Kreipe H et al. Quantitative cross-validation and content analysis of the 450k DNA methylation array from Illumina, Inc. BMC Res Notes 2012; 5: 210.

Tost J, Gut IG . DNA methylation analysis by pyrosequencing. Nat Protoc 2007; 2: 2265–2275.

Xiao L, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Sun Y, Sun W, Wang L et al. Identification of a novel human cancer/testis gene MAEL that is regulated by DNA methylation. Mol Biol Rep 2010; 37: 2355–2360.

Rees E, Walters JTR, Georgieva L, Isles AR, Chambert KD, Richards AL et al. Analysis of copy number variations at 15 schizophrenia-associated loci. Br J Psychiatry 2014; 204: 108–114.

Itsara A, Cooper GM, Baker C, Girirajan S, Li J, Absher D et al. Population analysis of large copy number variants and hotspots of human genetic disease. Am J Hum Genet 2009; 84: 148–161.

Do KQ, Cabungcal JH, Frank A, Steullet P, Cuenod M . Redox dysregulation, neurodevelopment, and schizophrenia. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2009; 19: 220–230.

Koga M, Serritella AV, Sawa A, Sedlak TW . Implications for reactive oxygen species in schizophrenia pathogenesis. Schizophr Res 2016 (in press).

Listowsky I . A subclass of mu glutathione S-transferases selectively expressed in testis and brain. Methods Enzymol 2005; 401: 278–287.

Knight TR, Choudhuri S, Klaassen CD . Constitutive mRNA expression of various glutathione S-transferase isoforms in different tissues of mice. Toxicol Sci 2007; 100: 513–524.

Hayes KR, Young BM, Pletcher MT . Expression quantitative trait loci mapping identifies new genetic models of glutathione S-transferase variation. Drug Metab Dispos 2009; 37: 1269–1276.

Gawryluk JW, Wang J-F, Andreazza AC, Shao L, Yatham LN, Young LT . Prefrontal cortex glutathione S-transferase levels in patients with bipolar disorder, major depression and schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2011; 14: 1069–1074.

Etcheverry A, Aubry M, de Tayrac M, Vauleon E, Boniface R, Guenot F et al. DNA methylation in glioblastoma: impact on gene expression and clinical outcome. BMC Genomics 2010; 11: 701.

Maness PF, Schachner M . Neural recognition molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily: signaling transducers of axon guidance and neuronal migration. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10: 19–26.

Kolata S, Wu J, Light K, Schachner M, Matzel LD . Impaired working memory duration but normal learning abilities found in mice that are conditionally deficient in the close homolog of L1. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 13505–13510.

Morellini F, Lepsveridze E, Kähler B, Dityatev A, Schachner M . Reduced reactivity to novelty, impaired social behavior, and enhanced basal synaptic excitatory activity in perforant path projections to the dentate gyrus in young adult mice deficient in the neural cell adhesion molecule CHL1. Mol Cell Neurosci 2007; 34: 121–136.

Chen Q-Y, Chen Q, Feng G-Y, Lindpaintner K, Chen Y, Sun X et al. Case-control association study of the close homologue of L1 (CHL1) gene and schizophrenia in the Chinese population. Schizophr Res 2005; 73: 269–274.

Sakurai K, Migita O, Toru M, Arinami T . An association between a missense polymorphism in the close homologue of L1 (CHL1, CALL) gene and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2002; 7: 412–415.

Tam GWC, van de Lagemaat LN, Redon R, Strathdee KE, Croning MDR, Malloy MP et al. Confirmed rare copy number variants implicate novel genes in schizophrenia. Biochem Soc Trans 2010; 38: 445–451.

Wright AG, Demyanenko GP, Powell A, Schachner M, Enriquez-Barreto L, Tran TS et al. Close homolog of L1 and neuropilin 1 mediate guidance of thalamocortical axons at the ventral telencephalon. J Neurosci 2007; 27: 13667–13679.

McIntyre JC, Titlow WB, McClintock TS . Axon growth and guidance genes identify nascent, immature, and mature olfactory sensory neurons. J Neurosci Res 2010; 88: 3243–3256.

Filosa A, Paixão S, Honsek SD, Carmona MA, Becker L, Feddersen B et al. Neuron-glia communication via EphA4/ephrin-A3 modulates LTP through glial glutamate transport. Nat Neurosci 2009; 12: 1285–1292.

Corvin A, Morris DW . Genome-wide association studies: findings at the major histocompatibility complex locus in psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 2014; 75: 276–283.

Andreassen OA, Harbo HF, Wang Y, Thompson WK, Schork AJ, Mattingsdal M et al. Genetic pleiotropy between multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia but not bipolar disorder: differential involvement of immune-related gene loci. Mol Psychiatry 2014; 20: 207–214.

Chan MK, Krebs M-O, Cox D, Guest PC, Yolken RH, Rahmoune H et al. Development of a blood-based molecular biomarker test for identification of schizophrenia before disease onset. Transl Psychiatry 2015; 5: e601.

Dimitrov DH, Lee S, Yantis J, Valdez C, Paredes RM, Braida N et al. Differential correlations between inflammatory cytokines and psychopathology in veterans with schizophrenia: potential role for IL-17 pathway. Schizophr Res 2013; 151: 29–35.

Lai W-S, Xu B, Westphal KGC, Paterlini M, Olivier B, Pavlidis P et al. Akt1 deficiency affects neuronal morphology and predisposes to abnormalities in prefrontal cortex functioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 16906–16911.

Balu DT, Carlson GC, Talbot K, Kazi H, Hill-Smith TE, Easton RM et al. Akt1 deficiency in schizophrenia and impairment of hippocampal plasticity and function. Hippocampus 2012; 22: 230–240.

Ikeda M, Iwata N, Suzuki T, Kitajima T, Yamanouchi Y, Kinoshita Y et al. Association of AKT1 with schizophrenia confirmed in a Japanese population. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 56: 698–700.

Di Forti M, Iyegbe C, Sallis H, Kolliakou A, Falcone MA, Paparelli A et al. Confirmation that the AKT1 (rs2494732) genotype influences the risk of psychosis in cannabis users. Biol Psychiatry 2012; 72: 811–816.

Nishioka M, Bundo M, Koike S, Takizawa R, Kakiuchi C, Araki T et al. Comprehensive DNA methylation analysis of peripheral blood cells derived from patients with first-episode schizophrenia. J Hum Genet 2013; 58: 91–97.

Dempster EL, Pidsley R, Schalkwyk LC, Owens S, Georgiades A, Kane F et al. Disease-associated epigenetic changes in monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Hum Mol Genet 2011; 20: 4786–4796.

Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, Ropero S, Setien F, Ballestar ML et al. Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102: 10604–10609.

Purcell SM, Moran JL, Fromer M, Ruderfer D, Solovieff N, Roussos P et al. A polygenic burden of rare disruptive mutations in schizophrenia. Nature 2014; 506: 185–190.

Wong CCY, Meaburn EL, Ronald A, Price TS, Jeffries AR, Schalkwyk LC et al. Methylomic analysis of monozygotic twins discordant for autism spectrum disorder and related behavioural traits. Mol Psychiatry 2013; 19: 495–503.

Masliah E, Dumaop W, Galasko D, Desplats P . Distinctive patterns of DNA methylation associated with Parkinson disease: identification of concordant epigenetic changes in brain and peripheral blood leukocytes. Epigenetics 2013; 8: 1030–1038.

Kaminsky Z, Tochigi M, Jia P, Pal M, Mill J, Kwan A et al. A multi-tissue analysis identifies HLA complex group 9 gene methylation differences in bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2012; 17: 728–740.

Walton E, Hass J, Liu J, Roffman JL, Bernardoni F, Roessner V et al. Correspondence of DNA methylation between blood and brain tissue and its application to schizophrenia research. Schizophr Bull 2015; 42: 406–414.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients and parents who participated in the ICAAR study and all other practitioners involved in the ICAAR study, the staff of the Clinical research center (Marie José Dos Santos, Caroline Gaillard, Aurélien Bongrand, Michèle Alabi) and C’JAAD (Centre d’Evaluation pour Jeunes Adultes et Adolescents, especially François Chauchot, Anne Gut, Emilie Magaud, Célia Mam-Lam-Fook, Mathilde Kazes) at Service Hospitalo-Universitaire, Centre Hospitalier Sainte-Anne for their role in subject’s assessment and follow-up as well as the data management, with a special thanks to Caroline Gaillard. We also thank the URC Paris Centre Descartes (AP-HP), INSERM and DRCI for reglementary and technical assistances. We are extremely grateful to Laure Ferry, Assistant Engineer in charge of the Functional Epigenomic Platform in UMR7216, for her excellent technical training of the pyrosequencing experiments, to Guillaume Velasco (Assistant Professor, UPD, for his invaluable help and advices and to the UMR7216 Platform Committee (Slimane Ait-Si-Ali, Jean-François Ouimette, Guillaume Velasco and Pierre Antoine-Defossez) for selecting our project. Thanks to Marwa Kharrat for her technical help in the initial steps of pyrosequencing. We acknowledge Simon Girard for his very crucial statistical advices, Bill P Godsil for the english editing and also to Kasper Daniel Hansen and Andres Houseman for their help in the use of bio-informatical pipelines This work was supported by the French Governement Agence Nationale pour la Recherche grant (ANR, 08-MNP-007) and by the French Ministry for Health grant Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (PHRC, AOM-07-118). Centre Hospitalier Sainte-Anne promoted the study. Additional financial supports were obtained from the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM, recurrent funding and fellowships BC), Université Paris Descartes (recurrent funding), Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (CML) and Fondation Deniker and Fonds Québécois de Recherche sur la Société et la Culture-INSERM joint grant (MOK, OK). The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. VM's laboratory, including FM by a postdoctoral fellowship, has been supported by Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (Program SAMENTA ANR-13-SAMA-0008-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Members of the ICAAR team Célia Mam-Lam-Fook, Charlotte Alexandre, Emilie Magaud, Gilles Martinez, Mathilde Kazes, Mélanie Chayet, Olivier Gay, Zelda Prost.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Molecular Psychiatry website

Supplementary information

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kebir, O., Chaumette, B., Rivollier, F. et al. Methylomic changes during conversion to psychosis. Mol Psychiatry 22, 512–518 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.53

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.53

This article is cited by

-

Exploring the mediation of DNA methylation across the epigenome between childhood adversity and First Episode of Psychosis—findings from the EU-GEI study

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

-

Dopamine-induced pruning in monocyte-derived-neuronal-like cells (MDNCs) from patients with schizophrenia

Molecular Psychiatry (2022)

-

Caught in vicious circles: a perspective on dynamic feed-forward loops driving oxidative stress in schizophrenia

Molecular Psychiatry (2022)

-

Reliability and correlation of mixture cell correction in methylomic and transcriptomic blood data

BMC Research Notes (2020)

-

Dysregulation of peripheral expression of the YWHA genes during conversion to psychosis

Scientific Reports (2020)