Abstract

Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm is a relatively recently described member of the pancreatic intraductal neoplasm family. The more common member of this family, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, often carries genetic alterations typical of pancreatic infiltrating ductal adenocarcinoma (KRAS, TP53, and CDKN2A) but additionally has mutations in GNAS and RNF43 genes. However, the genetic characteristics of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm have not been well characterized. Twenty-two intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms were analyzed by either targeted next-generation sequencing, which enabled the identification of sequence mutations, copy number alterations, and selected structural rearrangements involving all targeted (≥300) genes, or whole-exome sequencing. Three of these intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms were also subjected to whole-genome sequencing. All intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms revealed the characteristic histologic (cellular intraductal nodules of back-to-back tubular glands lined by predominantly cuboidal cells with atypical nuclei and no obvious intracellular mucin) and immunohistochemical (immunolabeled with MUC1 and MUC6 but were negative for MUC2 and MUC5AC) features. By genomic analyses, there was loss of CDKN2A in 5/20 (25%) of these cases. However, the majority of the previously reported intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm-related alterations were absent. Moreover, in contrast to most ductal neoplasms of the pancreas, MAP-kinase pathway was not involved. In fact, 2/22 (9%) of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms did not reveal any mutations in the tested genes. However, certain chromatin remodeling genes (MLL1, MLL2, MLL3, BAP1, PBRM1, EED, and ATRX) were found to be mutated in 7/22 (32%) of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms and 27% harbored phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway (PIK3CA, PIK3CB, INPP4A, and PTEN) mutations. In addition, 4/18 (18%) of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms had FGFR2 fusions (FGFR2-CEP55, FGFR2-SASS6, DISP1-FGFR2, FGFR2-TXLNA, and FGFR2-VCL) and 1/18 (5.5%) had STRN-ALK fusion. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm is a distinct clinicopathologic entity in the pancreas. Although its intraductal nature and some clinicopathologic features resemble those of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, our results suggest that intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm has distinguishing genetic characteristics. Some of these mutated genes are potentially targetable. Future functional studies will be needed to determine the consequences of these gene alterations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm is a relatively recently described member of the pancreatic intraductal neoplasm family.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 First reported by Tajiri et al.2 under the heading of intraductal tubular carcinoma in 2004, the entity is now designated intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm,11 although limited papilla formation is seen only in a minority of cases.1 The clinical findings of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm are often indistinguishable from those of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas, the prototype of the pancreatic intraductal neoplasm family. For example, both intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms present as a multinodular tumor with solid and cystic areas. Although the cystic areas may be less evident in intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms, their intraductal nature may be appreciated radiographically in some cases. Also, preliminary studies suggest that, similar to intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms are less aggressive neoplasms than conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, even if there is an associated invasive carcinoma.1, 10

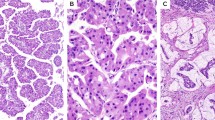

However, intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm has several distinguishing pathologic characteristics. Microscopically, the intraductal tumor nodules are typically cellular and punctuated by numerous tubules, which are prominent in most cases. The cells are cuboidal and relatively uniform but at the same time show substantial cytologic atypia. Although amorphous acidophilic secretions may be seen in rare cases, typically there is no visible intracytoplasmic mucin. In addition, the MUC expression profile of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm points to a gastro-pancreatic rather than intestinal lineage: MUC1 and MUC6 are expressed in most cases, while MUC2 and MUC4 are negative.1, 6, 10 MUC5AC is reported to be only occasionally positive.1, 12

With the introduction of routine genomic analyses, including next-generation sequencing,13, 14, 15 various genetic alterations have been identified in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. As in many ductal neoplasms including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, activating KRAS mutations are the most common mutations and have been detected in the majority of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms.14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 TP53 mutations occur in cases with high-grade dysplasia and CDKN2A may also be altered. More interestingly, activating GNAS mutations have been identified in approximately half of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms,14, 15, 23, 24, 25, 26 particularly in the intestinal subtype.14, 23, 25 Inactivating mutations in the RNF43 gene, a likely tumor suppressor and negative regulator of the Wnt signaling pathway,27 are also seen frequently in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms.14, 24 Less common alterations involve PIK3CA, SMAD4, BRAF, CTNNB1/β-catenin, IDH1, STK11, PTEN, ATM, CDH1, FGFR3, and SRC genes.16, 24, 28, 29, 30

However, data on the genetic features of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm are fairly limited, partially due to the rarity of the neoplasm. In one of the first reported cases of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm, transcriptional profiling analysis and subsequent correspondence cluster analysis demonstrated that the transcriptional profile of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm differed distinctly from that of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas and other pancreatic cystic tumors.31 Also, in contrast with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, KRAS, GNAS, and BRAF mutations have been very rarely reported in intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms.6, 7, 9, 12, 32

In the present study, we aimed to further define the genetic underpinnings of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm and analyzed 22 cases by targeted next-generation sequencing or whole-exome sequencing. Three of these cases were also subjected to whole-genome sequencing.

Materials and methods

With approval of the Institutional Review Boards, the surgical pathology databases of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Emory University, Ipatimup, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Tokyo Medical University, and Tohoku University were searched for patients with diagnoses of pancreatic intraductal tubular carcinoma or intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm. Twenty-two pancreatic neoplasms were identified for which the slides and tissue blocks were available. The diagnosis was confirmed by the authors for each case. Medical records including pathology reports were reviewed to obtain clinical data. The choice of sequencing platforms (see below) was based on assays available at the institutions in the United States and Japan where the cases were collected. All methods included the major genes known to be altered in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, including KRAS, TP53, CDKN2A, SMAD4, GNAS, and RNF43 (Supplementary Information Files 1a and 1b).

Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Using Illumina System (MSK-IMPACT)

Twenty 10-micron-thick sections of 18 cases (Cases #1–18) were cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks containing intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms. From these sections, areas of interest were needle micro-dissected. For each patient, extraction of DNA was performed on dissected tissue, and where available on normal, non-pancreatic tissue (stomach, spleen, or duodenum). Deep coverage, targeted next-generation sequencing was then performed for a panel of 300 genes, listed in the Supplementary Information File 1a, known to undergo somatic genomic alterations in cancer, as previously described.33, 34 Briefly, massively parallel sequencing libraries (Kapa Biosystems, New England Biolabs) that contain barcoded universal primers were generated from 115 to 250 ng genomic DNA from the tumor material and matched normal tissue. After library amplification and DNA quantification, pools of barcoded libraries were subjected to solution-phase hybrid capture with synthetic biotinylated DNA probes (Nimblegen SeqCap) targeting all protein-coding exons from all 300 target genes as well as introns known to harbor recurrent translocation breakpoints. Each hybrid capture pool was sequenced to deep coverage in a single paired-end lane of an Illumina flow cell. Subsequently, the sequencing data were analyzed to identify multiple classes of genomic alterations (single-nucleotide sequence variants, small insertions/deletions, and DNA copy number alterations). For matched tumor/normal tissue pairs (n=17), somatic single-nucleotide variants and insertions and deletions were called using MuTect and the SomaticIndelDetector tools in Genome Analysis Toolkit, respectively.35, 36 For the only unmatched tumor (n=1), MuTect was run against a pool of unrelated DNAs from normal formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues, and variants were filtered out if they were present in the 1000 Genomes project at a population frequency of >1%. All candidate mutations and insertions and deletions were reviewed manually using the Integrative Genomics Viewer.37 The mean coverage was 400 × for tumor DNA and 50 × for normal DNA.

Targeted Cancer Gene Panel Sequencing Using Ion Ampliseq System (Ion AmpliSeq)

Twelve-micron-thick sections of two additional cases (Cases # 19 and #20) were cut from frozen tissue blocks containing intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms. From these sections, areas of interest were needle micro-dissected. For each patient, extraction of DNA was performed on dissected tissue and on normal pancreatic tissue. Targeted next-generation sequencing was then performed on a panel of 409 genes using the Ion Ampliseq Comprehensive Cancer Panel (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) (Supplementary Information File 1b). Briefly, sequencing libraries that contain barcoded universal primers were generated from 10 ng genomic DNA from the tumor material and matched normal tissue using Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After library DNA quantification, equimolar pools were generated consisting of up to 20 barcoded libraries. Library pools were sequenced by using Ion Proton System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Subsequently, the sequencing data were deconvoluted to match all high-quality barcoded reads with the corresponding tumor samples, and genomic alterations (single-nucleotide sequence variants and small insertions/deletions) were identified. For matched tumor/normal tissue pairs, somatic single-nucleotide variants and insertions and deletions were called using Ion Reporter Software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mean coverage was 716 × for tumor DNA and 585 × for normal DNA.

Selected variations were validated by Sanger sequencing as follows: DNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction and the AccuPrime polymerase chain reaction system (Thermo Fishers Scientific). The amplified products were treated with ExoSAP-IT (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK) and sequenced using BigDye Terminator and a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fishers Scientific) according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Whole-Exome Sequencing Using SOLiD System

Tumor and normal tissues of another two cases (Cases #21 and #22) were dissected and collected separately from frozen sections under microscopic guidance. DNA was extracted using a ChargeSwitch gDNA Mini Tissue Kit (Thermo Fishers Scientific). The extracted DNA was constructed into a fragment library using the AB Library Builder System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Libraries were quantified by using Bioanalyzer system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). An appropriate amount of the constructed libraries were subjected to whole-exome enrichment using a TargetSeq Target Enrichment Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The prepared exome libraries were sequenced using the massively parallel deep sequencer 5500xl SOLiD System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the paired-end sequencing method. Data were analyzed using LifeScope software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with mapping on the Human Genome Reference, GRCh37/hg19. All procedures were performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Obtained data were annotated and stringently filtered to exclude false variation calls using our previously described programs developed in-house.15 Copy number variations were calculated using the exome sequencing data as described previously.38

The mean coverage was 129 × for tumor DNA and 81.5 × for normal DNA.

Whole-Genome Sequencing

Fresh frozen tumor material and matched normal tissues from three cases (Cases #7, #11, and #17) analyzed by MSK-IMPACT were also subjected to whole-genome sequencing at New York Genome Center, which was performed using Illumina paired-end chemistry on a HiSeqX sequencer at a coverage of at least 80 × for tumor DNA and 40 × for normal DNA.

For whole-genome sequencing and genotyping, DNA was extracted using Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit. DNA was quantified using the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer, Invitrogen and quality was determined by using Agilent Bioanlyzer. DNA libraries were prepared using the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (Kapa; Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA). For each sample library preparation, 100 ng of high molecular weight genomic DNA was fragmented using the Covaris LE220 system to an average size of 350 bp. Fragmented samples were end repaired and adenylated using Kapa’s end-repair and a-tailing enzymes. The samples were then ligated with Bioscientific adapters and polymerase chain reaction amplified using KAPA Hifi HotStart Master Mix (Kapa; Kapa Biosystems). The DNA libraries were clustered onto flowcells using Illumina’s cBot and HiSeq Paired End Cluster Generation kits as per the manufacturer's protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Sequencing was performed using 2 × 150 Illumina HiSeqX platform with v2.5 chemistry reagents. Genotyping was performed using HumanOmni2.5M BeadChips (Illumina).

Paired-end 2x150bp reads were aligned to the GRCh37 human reference using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA aln v.0.7.8)39 and processed using the best-practices pipeline that includes marking of duplicate reads by the use of Picard tools and realignment around insertions and deletions and base recalibration via Genome Analysis Toolkit ver. 2.7.4.40 We employ the following variant callers: muTect v1.1.4,35 LoFreq v2.0.041 (single-nucleotide sequence variants only), Strelka v1.0.1342 (both single-nucleotide sequence variants and insertions and deletions), Pindel43 and Scalpel44 (insertions and deletions only) and return the union of calls, filtered using the default filtering criteria as implemented in each of the callers. Single-nucleotide sequence variants and insertions and deletions were annotated via snpEff, snpSift45 and Genome Analysis Toolkit VariantAnnotator using annotation from ENSEMBL, COSMIC,46 Gene Ontology and 1000 Genomes.

Structural variants, such as copy number variants as well as complex genomic rearrangements, were detected by the use of multiple tools: NBIC-seq47 for copy number variant/structural variant calling, Delly,48 Crest,49 and BreakDancer50 for structural variant calling. We prioritized structural variants in the intersection of callers and structural variants for which we can find additional split-read evidence using SplazerS.51 Structural variants for which there was split-read support in the matched normal or that were annotated as known germline variants (1000 Genomes call set, DGV) were removed as likely remaining germline variants. The predicted sets of somatic structural variants were annotated with gene overlap (RefSeq, Cancer Gene Census) including prediction of potential effect on genes (eg, disruptive/exonic, intronic, intergenic, fusion candidate). In addition, copy number variants and loss of heterozygosity were also analyzed from the genotyping chip using Nexus (Biodiscovery) software.

Results

Clinicopathologic Features

The clinicopathologic features of the 22 cases (11 of which have been reported previously1) are summarized in Table 1. The mean patient age was 58 years, with a male to female ratio of 1.4. None of the patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation.

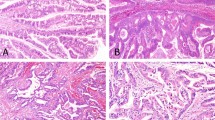

Overall tumor size varied from 0.9 to 16 cm. All tumors exhibited typical entity-defining characteristics. Grossly, they were multinodular and solid to cystic. Microscopically, the tumors consisted of variably sized circumscribed nodules of back-to-back glands, resulting in large cribriform structures surrounded by fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). Within the tumor nodules, there were tightly packed small glands lined by cuboidal cells. In most cases there was no obvious intracellular mucin in the neoplastic cells. The nuclei were atypical and mitotic figures were readily identifiable (Figure 2). Of 21 resection cases, 17 (81%) had invasion.

Follow-up information was available for 18 patients. One patient (Case #7) died of perioperative complications 1 month after the surgery. One patient (Case #22) died of other disease(s) after 5 months. Three patients (19%) (Cases #17, #21, and #15) died of disease after 20, 25, and 125 months, respectively. The remaining 13 (81%) were alive after 9–173months (median, 95). Of these, two patients (Cases #18 and #12) had a recurrence in the remainder of the pancreas after 9 and 12 months, respectively, and underwent completion pancreatectomy. Case #18 found to have lymph node metastases in the second surgery. Additional four patients (Cases #4, #15, #16, and #21) developed liver metastases after 78, 56, 10.5, and 17 months, respectively. Seven patients (44%) are alive without evidence of disease.

Molecular Features

Results of MSK-IMPACT, Ion AmpliSeq and Whole-Exome Sequencing

Twenty tumor/normal tissue pairs and one unmatched tumor tissue sample from the 18 patients underwent MSK-IMPACT (intraductal and invasive tumor components of Case #16 and tumors from both Whipple and completion pancreatectomy as well as lymph node metastasis of Case #18 were analyzed separately). Four tumor/normal tissue pairs from four Japanese patients were analyzed using either Ion AmpliSeq (Cases #19 and #20) or whole-exome sequencing (Cases #21 and #22). The results of these genetic studies are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, and details regarding each of the individual tumors are described in the Supplementary Information Files 2–4.

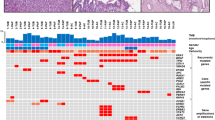

By copy number analysis, 80% of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms (16/20, due to the lack of copy number alteration data from Ion AmpliSeq) were found to have gene amplifications and deletions, including loss of heterozygosity or copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity in whole or parts of chromosome arm 1p and recurrent gains/amplifications in chromosome arm 1q and 8 (Figure 3). There was also amplification of MCL1 in 40% (8/20) and loss of CDKN2A in 25% (5/20). One case (Case #21) revealed amplification of MCL3 as well as hemizygous loss of MLL2 and BAP1.

Landscape of copy number alterations for intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm. Allele-specific integer copy number analysis using FACETS revealed recurrent loss of heterozygosity in chromosome 1p and recurrent gains in chromosomes 1q and 8. CN-LOH, copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity; LOH, loss of heterozygosity.

Except rare PIK3CA (Cases #13, #14, #21), PIK3CB (Case #20), PTEN (Case #7), and BRCA2 (Case #6) mutations, the previously reported intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas-related mutations (eg, KRAS, GNAS, RNF43, TP53, SMAD4) were not identified in these intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms. In fact, three tumors (Cases #4, #8, and #17) did not reveal any mutations by these methods. Others harbored mutations in genes involved in several additional signaling pathways pertinent to cancer biology such as chromatin remodeling pathway (MLL1 in Case #14, MLL2 in Cases #1 and #2, MLL3 in Case #5, BAP1 in Case #9, PBRM1 in Case #11, EED in Case #13, and ATRX in Case #14), WNT-β catenin pathway (CTNNB1 in Case #21, APC in Case #22, and AXIN1 in Case #11), GAS6-AXL pathway (AXL in Case #20), Rho pathway (ARHGAP26 in Case #1, ARHGAP35 in Case #21, ROR2 in Case #1, and KALRN in Case #22), tyrosine kinase pathway (KDR in Case #10, FLT4 in Case #11, NTRK in Case #15, and RET in Case #18), and ephrin pathway (EPHA2 in Case #6 and EPHB3 in Case #21).

Interestingly, there was no difference between the separately analyzed intraductal and invasive tumor components of Case #16; both component revealed the same ZFHX3 mutation (non-frameshift deletion). In contrast, separately analyzed primary and recurrent pancreatic tumors of Case# 18 found to have different mutations (Table 2). However, primary and recurrent pancreatic tumors as well as celiac lymph node metastasis of this case harbored the same ALK fusion (see below).

Of note, one of our patients (Case #22) had a history of neurofibromatosis type 1 (von-Recklinghausen’s disease). Although we did not find any germline mutation in coding exons of NF1 or NF2, we identified a somatic mutation in NF1 (missense mutation at S82F) in this patient’s tumor. The tumor also harbored a rare somatic mutation type in KRAS (missense mutation at A59E), which is different from common mutations found in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas that usually involve codon 12, 13, or 61.

In addition, 22% (4/18, due to the lack of fusion data from Ion AmpliSeq and whole-exome sequencing) of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms revealed FGFR2 fusions (three in frame, one out of frame, and one mid-exon fusions) and 5.5% (1/18) revealed an ALK fusion (a deletion, which results in an in-frame fusion of STRN exon 3 and ALK exon 20) (Table 3) (STRN-ALK fusion was also confirmed by Archer FusionPlexTM Custom Solid Panel utilizing the Anchored Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (AMPTM) technology to detect gene fusions in tumor samples. The panel consists of 35 cancer-related genes previously reported to be involved in chromosomal rearrangements).

Results of Whole-Genome Sequencing

Fresh frozen tumor samples from three patients (Cases #7, #11, and #17) analyzed by MSK-IMPACT also underwent whole-genome sequencing. Details of the individual tumors are described in Supplementary Information Files 5 and 6.

By copy number analysis, similar to MSK-IMPACT, Cases #7 and #17 were found to have multiple copy number gains and losses in multiple chromosomes. No significant copy number alterations were identified in Case #11.

Mutation assessment revealed a total of 129 mutations within these three tumors, 67 mutations in Case #7, 28 in Case #11, and 34 in Case #17. Similar to MSK-IMPACT, whole-genome sequencing did not identify the vast majority of well-recognized intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm-related (or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma-related) alterations. In fact, among the mutations identified by MSK-IMPACT, only NPM1 and PTEN mutations were also detected by whole-genome sequencing, likely due to lower coverage of target regions with whole-genome sequencing. Of note, one case revealed a MUC6 mutation (missense mutation, p.Pro1841Thr), which is not included in the panel of MSK-IMPACT.

Discussion

Recent studies have helped to better characterize the prototype of the pancreatic intraductal neoplasm family, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm,14, 24, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58 and have shown that the progression from intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with low-grade dysplasia to intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with associated invasive carcinoma is accompanied by a high number of molecular alterations (about 26 mutations per neoplasm), the most frequent ones being mutations in KRAS, GNAS, and RNF43.14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 These data have confirmed that intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm has both similarities and differences in genetic progression patterns compared with conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.18, 28, 59, 60, 61

However, the genetic characteristics of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm, the new member of the pancreatic intraductal neoplasm family,1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 62 have not been fully characterized yet as emerging studies have analyzed only selected gene mutations or a small number of cases.6, 7, 9, 24, 32 For example, in a recent study based on targeted next-generation sequencing for a panel of 51 cancer-associated genes, no mutations were identified in three intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms analyzed; although one case with coexisting intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm and intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm lesions revealed the same GNAS R201H mutation in both lesions and the intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm also had an additional NRAS Q61L mutation.24 With possible evidence to the contrary, in their investigation of somatic mutations in KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT1 in 11 intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms and 50 intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, Yamaguchi et al. identified PIK3CA mutations in 3 (27%) intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms, but in none of the intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. PIK3CA mutations were also significantly associated with strong immunoexpression of phosphorylated AKT in their cases. In contrast, mutations in KRAS were found in none of the intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms but were found in 26 (52%) intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms.7 In a subsequent study, the same group investigated somatic mutations in KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, and GNAS in 14 intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms and 15 gastric-subtype intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms.9 Similar to their first study, they identified PIK3CA mutations in three (21%) intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms, but in none of the intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Also, KRAS mutations were found in only 1 (7%) intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm and 12 (80%) intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, BRAF mutation in only 1 (7%) intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm, and GNAS mutations only in 9 (60%) intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms.9 A recent molecular analysis of the biliary counterpart of these neoplasms also revealed the very low prevalence of alterations in common oncogenic signaling pathways in 20 biliary intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms.63

In this study, we explored the genetic characteristics of 22 intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms, the largest series analyzed to date, by high depth targeted next-generation sequencing for large panels of key cancer-associated genes (MSK-IMPACT or Ion AmpliSeq) or by whole-exome sequencing. Selected intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms were also subjected to whole-genome sequencing. Our results show that, although loss of CDKN2A appears to be present at least in a subset (%25), intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms do not commonly harbor the previously reported intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm-related (or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma-related) alterations. However, consistent with the findings of Yamaguchi et al.,7, 9 six (27%) intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms harbored phosphatidylinositol pathway mutations (three PIK3CA, one PIK3CB, one INPP4A, and one PTEN mutation). In addition, certain chromatin remodeling genes (MLL1, MLL2, MLL3, BAP1, PBRM1, EED, and ATRX) were found to be mutated in seven (32%) intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms. Eight (40%) intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms also had MCL1 amplification.

MLL1 (KMT2A), MLL2 (KMT2D), and MLL3 (KMT2C) are members of the myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) family. Each gene encodes a different component of a histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferase complex and is responsible for the transcriptional regulation of developmental genes including the homeobox gene family.64 These genes have also been implicated as tumor suppressors due to their frequent mutations in multiple types of human tumors. For example, mutations of MLL2 are common in various types of B-cell lymphoma65 and are reported in epithelial tumors such as non-small cell lung carcinoma66 and renal cell carcinoma.67 Mutations and LOH of MLL3 are reported in various types of lymphoma, as well as in gastrointestinal carcinomas, including cholangiocarcinoma,68, 69, 70, 71 and urothelial carcinoma.72 Similarly, BAP1, belongs to the family of deubiquitinating enzymes, encodes an enzyme that binds to the breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein (BRCA1), and acts as a tumor suppressor.73, 74 Mutations of BAP1 are one of the frequent inactivating mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas75, 76 and mesotheliomas.77, 78 Finally, MCL1 is involved in the regulation of apoptosis versus cell survival, and in the maintenance of viability. It mediates its effects by interactions with a number of other regulators of apoptosis.79, 80 MCL1 is frequently amplified in neural, lung, breast, and gastrointestinal cancers.81

In a recent study, potential involvement of somatic mutations in chromatin remodeling genes including MLL2 and MLL3 has also been reported in 20% of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients who have prolonged overall and progression-free survival, compared with wild-type tumors, and these observations appear to be independent of other clinical variables.82 Similarly, mutation of other epigenetic regulators has been described in other pancreatic neoplasms and has been associated with clinical outcome. For instance, improved outcome was reported in patients with DAXX/ATRX alterations in metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors,83 although primary tumors with DAXX/ATRX mutations appear to have a poorer outcome.84 Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms, even if they have an associated invasive carcinoma, are also less aggressive compared with conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas.10 Therefore, whether tumors significantly driven by mutations in epigenetic regulators may be inherently less aggressive is an intriguing speculation, and genetic alterations identified in this study are likely to be more than mere epiphenomena for their potential role in the tumorigenesis of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms.

More importantly, some of these genetic alterations might be potentially targetable. For example, PIK3CA mutation is of special interest as it is a potential therapeutic target for inhibition of the PI3K pathway.85, 86 Similarly, BAP1 mutation may also confer sensitivity to drugs targeting chromatin remodeling, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors.87 Multiple FGFR2 (fibroblast growth factor receptor 2) fusions, including a previously described FGFR2-TXLNA fusion,88 detected in four (22%) intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms are also of importance. FGFR2 fusions, an important class of genetic driver, have been detected in a diverse array of cancer types including cholangiocarcinoma, breast carcinoma, and lung squamous cell carcinoma among others.89, 90, 91, 92 Moreover, several independent studies reported that cells harboring FGFR fusions show enhanced sensitivity to the FGFR inhibitors, suggesting that the presence of FGFR fusions may be a useful biomarker of tumor response to FGFR inhibitors.89, 92

In summary, the present comprehensive analysis helps validate the morphologic distinction of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm from other types of pancreatic neoplasms. More importantly, it demonstrates potentially targetable genetic alterations in intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms, such as kinases (PIK3CA and FGFR2) and tumor-suppressor genes (BAP1 and BRCA2). Further analysis of these genetic alterations in biologically distinct pathway will likely shed new light on the mechanisms of intraductal tumor formation in the pancreas and reveal new therapeutic targets for patients with these neoplasms.

References

Basturk O, Adsay V, Askan G et al. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 33 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41:313–325.

Tajiri T, Tate G, Kunimura T et al. Histologic and immunohistochemical comparison of intraductal tubular carcinoma, intraductal papillary-mucinous carcinoma, and ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Pancreas 2004;29:116–122.

Tajiri T, Tate G, Inagaki T et al. Intraductal tubular neoplasms of the pancreas: histogenesis and differentiation. Pancreas 2005;30:115–121.

Itatsu K, Sano T, Hiraoka N et al. Intraductal tubular carcinoma in an adenoma of the main pancreatic duct of the pancreas head. J Gastroenterol 2006;41:702–705.

Oh DK, Kim SH, Choi SH et al. Intraductal tubular carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report with the imaging findings. Korean J Radiol 2008;9:473–476.

Yamaguchi H, Shimizu M, Ban S et al. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas distinct from pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1164–1172.

Yamaguchi H, Kuboki Y, Hatori T et al. Somatic mutations in PIK3CA and activation of AKT in intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:1812–1817.

Kasugai H, Tajiri T, Takehara Y et al. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: case report and review of the literature. J Nippon Med Sch 2013;80:224–229.

Yamaguchi H, Kuboki Y, Hatori T et al. The discrete nature and distinguishing molecular features of pancreatic intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the gastric type, pyloric gland variant. J Pathol 2013;231:335–341.

Date K, Okabayashi T, Shima Y et al. Clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: a systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2016;401:439–447.

Adsay NV, Klöppel G, Fukushima N et al.Intraductal neoplasms of the pancreas. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH et al. (eds). WHO Classification of Tumors, 4th edn. IARC: Lyon, 2010, pp 304–313.

Muraki T, Uehara T, Sano K et al. A case of MUC5AC-positive intraductal neoplasm of the pancreas classified as an intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm? Pathol Res Pract 2015;211:1034–1039.

Fritz S, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Mino-Kenudson M et al. Global genomic analysis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas reveals significant molecular differences compared to ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2009;249:440–447.

Wu J, Jiao Y, Dal Molin M et al. Whole-exome sequencing of neoplastic cysts of the pancreas reveals recurrent mutations in components of ubiquitin-dependent pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:21188–21193.

Furukawa T, Kuboki Y, Tanji E et al. Whole-exome sequencing uncovers frequent GNAS mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Sci Rep 2011;1:161.

Schonleben F, Qiu W, Bruckman KC et al. BRAF and KRAS gene mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm/carcinoma (IPMN/IPMC) of the pancreas. Cancer Lett 2007;249:242–248.

Z'Graggen K, Rivera JA, Compton CC et al. Prevalence of activating K-ras mutations in the evolutionary stages of neoplasia in intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas. Ann Surg 1997;226:491–500.

Sessa F, Solcia E, Capella C et al. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumours represent a distinct group of pancreatic neoplasms: an investigation of tumour cell differentiation and K-ras, p53 and c-erbB-2 abnormalities in 26 patients. Virchows Arch 1994;425:357–367.

Almoguera C, Shibata D, Forrester K et al. Most human carcinomas of the exocrine pancreas contain mutant c-K-ras genes. Cell 1988;53:549–554.

Kitago M, Ueda M, Aiura K et al. Comparison of K-ras point mutation distributions in intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors and ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Int J Cancer 2004;110:177–182.

Klöppel G, Basturk O, Schlitter AM et al. Intraductal neoplasms of the pancreas. Semin Diagn Pathol 2014;31:452–466.

Jang JY, Park YC, Song YS et al. Increased K-ras mutation and expression of S100A4 and MUC2 protein in the malignant intraductal papillary mucinous tumor of the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2009;16:668–674.

Dal Molin M, Matthaei H, Wu J et al. Clinicopathological correlates of activating GNAS mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:3802–3808.

Amato E, Molin MD, Mafficini A et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of cancer genes dissects the molecular profiles of intraductal papillary neoplasms of the pancreas. J Pathol 2014;233:217–227.

Wu J, Matthaei H, Maitra A et al. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development. Sci Transl Med 2011;3:92ra66.

Tan MC, Basturk O, Brannon AR et al. GNAS and KRAS mutations define separate progression pathways in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm-associated carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 2015;220:845–854.e1.

Jiang X, Hao HX, Growney JD et al. Inactivating mutations of RNF43 confer Wnt dependency in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:12649–12654.

Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Klimstra DS, Adsay NV et al. Dpc-4 protein is expressed in virtually all human intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: comparison with conventional ductal adenocarcinomas. Am J Pathol 2000;157:755–761.

Schonleben F, Qiu W, Ciau NT et al. PIK3CA mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm/carcinoma of the pancreas. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:3851–3855.

Schonleben F, Qiu W, Remotti HE et al. PIK3CA, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm/carcinoma (IPMN/C) of the pancreas. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008;393:289–296.

Esposito I, Bauer A, Hoheisel JD et al. Microcystic tubulopapillary carcinoma of the pancreas: a new tumor entity? Virchows Arch 2004;444:447–453.

Furukawa T, Hatori T, Fukuda A et al. Intraductal tubular carcinoma of the pancreas: case report with molecular analysis. Pancreas 2009;38:235–237.

Won HH, Scott SN, Brannon AR et al. Detecting somatic genetic alterations in tumor specimens by exon capture and massively parallel sequencing. J Vis Exp 2013;80:50710.

Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): a hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for solid tumor molecular oncology. J Mol Diagn 2015;17:251–264.

Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31:213–219.

DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet 2011;43:491–498.

Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 2011;29:24–26.

Furukawa T, Sakamoto H, Takeuchi S et al. Whole exome sequencing reveals recurrent mutations in BRCA2 and FAT genes in acinar cell carcinomas of the pancreas. Sci Rep 2015;5:8829.

Li H, Durbin R . Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009;25:1754–1760.

McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010;20:1297–1303.

Wilm A, Aw PP, Bertrand D et al. LoFreq: a sequence-quality aware, ultra-sensitive variant caller for uncovering cell-population heterogeneity from high-throughput sequencing datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:11189–11201.

Saunders CT, Wong WS, Swamy S et al. Strelka: accurate somatic small-variant calling from sequenced tumor-normal sample pairs. Bioinformatics 2012;28:1811–1817.

Ye K, Schulz MH, Long Q et al. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics 2009;25:2865–2871.

Narzisi G, O'Rawe JA, Iossifov I et al. Accurate de novo and transmitted indel detection in exome-capture data using microassembly. Nat Methods 2014;11:1033–1036.

Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 2012;6:80–92.

Forbes SA, Bindal N, Bamford S et al. COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39:D945–D950.

Xi R, Hadjipanayis AG, Luquette LJ et al. Copy number variation detection in whole-genome sequencing data using the Bayesian information criterion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:E1128–E1136.

Rausch T, Zichner T, Schlattl A et al. DELLY: structural variant discovery by integrated paired-end and split-read analysis. Bioinformatics 2012;28:i333–i339.

Wang J, Mullighan CG, Easton J et al. CREST maps somatic structural variation in cancer genomes with base-pair resolution. Nat Methods 2011;8:652–654.

Chen K, Wallis JW, McLellan MD et al. BreakDancer: an algorithm for high-resolution mapping of genomic structural variation. Nat Methods 2009;6:677–681.

Emde AK, Schulz MH, Weese D et al. Detecting genomic indel variants with exact breakpoints in single- and paired-end sequencing data using SplazerS. Bioinformatics 2012;28:619–627.

Hruban RH, Takaori K, Klimstra DS et al. An illustrated consensus on the classification of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:977–987.

Luttges J, Zamboni G, Longnecker D et al. The immunohistochemical mucin expression pattern distinguishes different types of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas and determines their relationship to mucinous noncystic carcinoma and ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:942–948.

Nakamura A, Horinouchi M, Goto M et al. New classification of pancreatic intraductal papillary-mucinous tumour by mucin expression: its relationship with potential for malignancy. J Pathol 2002;197:201–210.

Terris B, Dubois S, Buisine MP et al. Mucin gene expression in intraductal papillary-mucinous pancreatic tumours and related lesions. J Pathol 2002;197:632–637.

Yonezawa S, Horinouchi M, Osako M et al. Gene expression of gastric type mucin (MUC5AC) in pancreatic tumors: its relationship with the biological behavior of the tumor. Pathol Int 1999;49:45–54.

Adsay NV, Merati K, Basturk O et al. Pathologically and biologically distinct types of epithelium in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: delineation of an "intestinal" pathway of carcinogenesis in the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:839–848.

Yonezawa S, Nakamura A, Horinouchi M et al. The expression of several types of mucin is related to the biological behavior of pancreatic neoplasms. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2002;9:328–341.

Biankin AV, Biankin SA, Kench JG et al. Aberrant p16(INK4A) and DPC4/Smad4 expression in intraductal papillary mucinous tumours of the pancreas is associated with invasive ductal adenocarcinoma. Gut 2002;50:861–868.

Yamaguchi K, Chijiiwa K, Noshiro H et al. Ki-ras codon 12 point mutation and p53 mutation in pancreatic diseases. Hepatogastroenterology 1999;46:2575–2581.

Sato N, Fukushima N, Maitra A et al. Gene expression profiling identifies genes associated with invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Pathol 2004;164:903–914.

Chelliah A, Kalimuthu S, Chetty R . Intraductal tubular neoplasms of the pancreas: an overview. Ann Diagn Pathol 2016;24:68–72.

Schlitter AM, Jang KT, Klöppel G et al. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms of the bile ducts: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 20 cases. Mod Pathol 2015;28:1249–1264.

Milne TA, Briggs SD, Brock HW et al. MLL targets SET domain methyltransferase activity to Hox gene promoters. Mol Cell 2002;10:1107–1117.

Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature 2011;476:298–303.

Yin S, Yang J, Lin B et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of MLL2 in non-small cell lung carcinoma from Chinese patients. Sci Rep 2014;4:6036.

Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature 2010;463:360–363.

Xiao HD, Yamaguchi H, Dias-Santagata D et al. Molecular characteristics and biological behaviours of the oncocytic and pancreatobiliary subtypes of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. J Pathol 2011;224:508–516.

Watanabe Y, Castoro RJ, Kim HS et al. Frequent alteration of MLL3 frameshift mutations in microsatellite deficient colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e23320.

Gao YB, Chen ZL, Li JG et al. Genetic landscape of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet 2014;46:1097–1102.

Li B, Liu HY, Guo SH et al. Association of MLL3 expression with prognosis in gastric cancer. Genet Mol Res 2014;13:7513–7518.

Nickerson ML, Witte N, Im KM et al. Molecular analysis of urothelial cancer cell lines for modeling tumor biology and drug response. Oncogene 2017;36:35–46.

Jensen DE, Proctor M, Marquis ST et al. BAP1: a novel ubiquitin hydrolase which binds to the BRCA1 RING finger and enhances BRCA1-mediated cell growth suppression. Oncogene 1998;16:1097–1112.

Nishikawa H, Wu W, Koike A et al. BRCA1-associated protein 1 interferes with BRCA1/BARD1 RING heterodimer activity. Cancer Res 2009;69:111–119.

Chan-On W, Nairismagi ML, Ong CK et al. Exome sequencing identifies distinct mutational patterns in liver fluke-related and non-infection-related bile duct cancers. Nat Genet 2013;45:1474–1478.

Moeini A, Sia D, Bardeesy N et al. Molecular pathogenesis and targeted therapies for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:291–300.

Ladanyi M, Zauderer MG, Krug LM et al. New strategies in pleural mesothelioma: BAP1 and NF2 as novel targets for therapeutic development and risk assessment. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:4485–4490.

Zauderer MG, Bott M, McMillan R et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma harboring somatic BAP1 mutations. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:1430–1433.

Bingle CD, Craig RW, Swales BM et al. Exon skipping in Mcl-1 results in a bcl-2 homology domain 3 only gene product that promotes cell death. J Biol Chem 2000;275:22136–22146.

Maurer U, Charvet C, Wagman AS et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulates mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and apoptosis by destabilization of MCL-1. Mol Cell 2006;21:749–760.

Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature 2010;463:899–905.

Sausen M, Phallen J, Adleff V et al. Clinical implications of genomic alterations in the tumour and circulation of pancreatic cancer patients. Nat Commun 2015;6:7686.

Jiao Y, Shi C, Edil BH et al. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science 2011;331:1199–1203.

Marinoni I, Kurrer AS, Vassella E et al. Loss of DAXX and ATRX are associated with chromosome instability and reduced survival of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Gastroenterology 2014;146:453–460.

Noel MS, Hezel AF . New and emerging treatment options for biliary tract cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2013;6:1545–1552.

Voss JS, Holtegaard LM, Kerr SE et al. Molecular profiling of cholangiocarcinoma shows potential for targeted therapy treatment decisions. Hum Pathol 2013;44:1216–1222.

Ma X, Ezzeldin HH, Diasio RB . Histone deacetylase inhibitors: current status and overview of recent clinical trials. Drugs 2009;69:1911–1934.

Nakamura H, Arai Y, Totoki Y et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nat Genet 2015;47:1003–1010.

Wu YM, Su F, Kalyana-Sundaram S et al. Identification of targetable FGFR gene fusions in diverse cancers. Cancer Discov 2013;3:636–647.

Arai Y, Totoki Y, Hosoda F et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 tyrosine kinase fusions define a unique molecular subtype of cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2014;59:1427–1434.

Sia D, Losic B, Moeini A et al. Massive parallel sequencing uncovers actionable FGFR2-PPHLN1 fusion and ARAF mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Commun 2015;6:6087.

Borad MJ, Champion MD, Egan JB et al. Integrated genomic characterization reveals novel, therapeutically relevant drug targets in FGFR and EGFR pathways in sporadic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS Genet 2014;10:e1004135.

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by a gift from the Farmer Family Foundation as well as by the Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG)/Core Grant/P30 CA008748 and JSPS KAKENHI Grant JP26460458. We also thank Ms Tanisha Daniel for her assistance during manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This study was presented in part at the 103rd annual meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology in Boston, MA, in March 2015.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Modern Pathology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Basturk, O., Berger, M., Yamaguchi, H. et al. Pancreatic intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm is genetically distinct from intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm and ductal adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 30, 1760–1772 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.60

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.60

This article is cited by

-

Reticular Myxoid Odontogenic Neoplasm with Novel STRN::ALK Fusion: Report of 2 Cases in 3-Year-Old Males

Head and Neck Pathology (2024)

-

Improving the prognosis of pancreatic cancer: insights from epidemiology, genomic alterations, and therapeutic challenges

Frontiers of Medicine (2023)

-

Integrative characterization of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm (ITPN) of the pancreas and associated invasive adenocarcinoma

Modern Pathology (2022)

-

Early detection of pancreatic cancer using DNA-based molecular approaches

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology (2021)

-

Salivary Intraductal Carcinoma Arising within Intraparotid Lymph Node: A Report of 4 Cases with Identification of a Novel STRN-ALK Fusion

Head and Neck Pathology (2021)