Abstract

A pattern-based classification for invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma has been proposed as predictive of the risk of nodal metastases. We aimed to determine the reproducibility of such classification in the context of common diagnostic challenges: distinction between in situ and invasive adenocarcinoma and depth of invasion measurement. Nine gynecologic pathologists independently reviewed 96 cases of endocervical adenocarcinoma (two slides per case). They diagnosed each case as in situ or invasive carcinoma classifying the latter following the pattern-based classification as pattern A (non-destructive), B (focally destructive) or C (diffusely destructive). Depth of invasion, when applicable, was measured (mm). Overall, diagnostic reproducibility of pattern diagnosis was good (κ=0.65). Perfect agreement (9/9 reviewers) was seen in only 11 cases (11%), all destructively invasive (10 pattern C and 1 pattern B). In all, ≥5/9 reviewer concordance was achieved in 82/96 cases (85%). Distinction between in situ and invasive carcinoma, regardless of the pattern, showed only slight agreement (κ=0.37). Likewise, distinction restricted to in situ versus pattern A was poor (κ=0.23). Distinction between non-destructive (in situ+pattern A) and destructive (patterns B+C) carcinoma showed significantly higher agreement (κ=0.62). Estimation of depth of invasion showed excellent reproducibility (ICC=0.82). However, different measurements resulting in differing FIGO stages were common (from at least 1 reviewer in 79% cases). On the basis of interobserver agreement, the pattern-based classification is best at diagnosing destructive invasion, which carries a risk for nodal metastases. Agreement in diagnosing in situ versus invasive carcinoma, including pattern A, was poor. Given the nil risk of nodal spread in in situ and pattern A lesions, the term ‘endocervical adenocarcinoma with non-destructive growth’ can be considered when the distinction is difficult, after excluding destructive invasion. Depth of invasion measurement was highly reproducible among pathologists; thus, the pattern-based approach can complement, but should not replace, the depth of invasion metric.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Staging of early (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I) invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma is currently based on the measurement of tumor width and depth of invasion with respect to the mucosal surface.1 Classification according to tumor dimensions identifies early lesions (stage IA, superficially invasive carcinoma), which have a negligible risk of nodal spread compared with tumors stage IB or larger. Estimation of the depth of invasion and tumor width can be challenging, particularly when tissue is not properly oriented, the mucosal surface is disrupted or when tumor is only partially sampled (as in biopsy and loop electrosurgical excision material).

A novel classification system based on the pattern, rather than the size of the invasive component, has been recently proposed by Diaz de Vivar et al,2 and subsequently by Roma et al3 in a follow-up analysis of the initial cohort. This system divides invasive tumors into three groups according to the pattern of stromal invasion (see Table 1).

The original studies demonstrated that tumors with a non-destructive pattern of invasion (pattern A) were associated with a 0% rate of lymph-node metastases, whereas focally (B) and diffusely (C) destructive patterns had 4 and 23% rates of nodal involvement, respectively.2, 3 Such associations have been recently validated by an independent multi-institutional study.4 In addition, tumor recurrences and death of disease to date have only been associated with destructive invasive patterns.5 Given this mounting evidence, the pattern-based classification has been proposed as a more reliable method to identify patients at risk of advanced stage and adverse outcome, compared with the traditional staging system based on the tumor size.

Interobserver variation of the pattern-based classification appears to be acceptable.6 However, assessment of reproducibility among practicing gynecologic pathologists in a large, multi-institutional study is still necessary. In addition, application of a pattern-based approach to endocervical glandular neoplasia deserves some considerations. First, the pattern-based classification applies to invasive adenocarcinoma only, thus areas of adenocarcinoma in situ need to be excluded from the pattern evaluation. However, the distinction between invasive and in situ adenocarcinoma is a well-known diagnostic challenge, and it has been reported that such distinction is impossible to achieve in as much as 20% of cases.7, 8 In addition, diagnostic reproducibility of depth of invasion measurement has not been fully documented and compared with that of the proposed pattern-based system.

In this multi-institutional study we sought to (1) determine the interobserver agreement of the pattern-based classification and distinction between in situ and invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma among gynecologic pathologists, (2) compare such agreement to that of depth of invasion measurement and (3) evaluate lymph-node status and clinical outcome with respect to the invasive carcinoma pattern.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Boards of all participating institutions at the time of data collection and analysis.

Case Selection

Cases diagnosed as invasive or in situ endocervical adenocarcinoma in cone biopsy, trachelectomy or hysterectomy specimens were retrieved from the archives of The Ottawa Hospital (from 2010 to 2015) and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (from 2005 to 2015). One gynecologic pathologist (CPH) reviewed all the histologic material available. Endocervical adenocarcinomas of usual (endocervical) type were selected; other adenocarcinoma histotypes (clear cell, gastric, metastatic) were excluded. In each case, two glass slides containing the largest amount of tumor were selected. In cases diagnosed as in situ adenocarcinoma, slides with neoplasia involving more than 50% of the glands were selected. This criterion was followed in order to have a relatively uniform set of slides in terms of tumor volume. Clinical information was recorded including patient age and, when applicable, tumor size, lymph-node status and FIGO pathologic stage, as well as status at time of follow-up.

Pathologist Review

Selected histologic material was independently reviewed by nine gynecologic pathologists representing seven academic institutions and diverse schools of subspecialty training (CR, LS, JKS, RRL, CMQ, AL, GR, MRN and BEH). Four pathologists had been in practice for more than 3 years at the time of review, whereas 5 were in their first 3 years of practice. In each slide, reviewers were asked to determine whether adenocarcinoma in situ was present or absent. They also determined whether there was invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma, and classified it based on the pattern of invasion as pattern A, B or C. References outlining criteria for pattern-based classification were provided.2, 3 Reviewers then assigned a final diagnosis to each case reviewed among these four categories: adenocarcinoma in situ, invasive adenocarcinoma pattern A, invasive adenocarcinoma pattern B and invasive adenocarcinoma pattern C. Finally, each reviewer recorded the largest depth of tumor invasion in mm (if invasion was considered to be present).

Statistical Analysis

Interobserver agreement was calculated using Fleiss’ generalized Kappa coefficient for multiple raters and Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), both with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals.9, 10 ICC was calculated using the two-way ANOVA method described by Shrout and Fleiss.11 Quadratic weights were used for the overall pattern classifications. Only ICC was calculated for depth of invasion measurement as it is a continuous variable. Percentage agreement was calculated as the number of agreements between all possible pairs of raters divided by the total number of agreements plus disagreements.10 The unit of analysis was the individual classifications with pathologist effects assumed to be random. Subgroup analyses were carried out by years of experience (≤3 years or >3 years). Analyses were conducted using SAS v.9.3 (SAS® for Mixed Models, 2nd ed., Cary, NC, USA) and R statistical software (R version 2.14.1, 2011, Vienna, Austria, http://R-project.org/).

Results

After review of the material available, 96 specimens of usual (endocervical) type endocervical adenocarcinoma from 94 patients were included (32 cases from The Ottawa Hospital and 64 cases from Brigham & Women’s Hospital). Nineteen cases were retrieved with a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma in situ and seventy-seven cases with a diagnosis of invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma.

Interobserver Agreement: Adenocarcinoma In situ and Invasive Endocervical Adenocarcinoma Classified by Pattern of Invasion

Distribution of diagnoses by each reviewer is depicted in Figure 1, and the corresponding agreements determined by ICC, Kappa (κ) and percentage of agreement are displayed in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Levels of agreement (y axis) among different diagnostic category comparisons (x axis). Agreement is measured in Kappa (for ordinal variables) and intraclass correlation coefficient (for depth of invasion). Agreement ranges from 0 (poor agreement) to 1 (perfect agreement). Middle value in each set corresponds to calculated Kappa/ICC; upper and lower values correspond to the 95% confidence interval. ACIS, adenocarcinoma in situ, CA, carcinoma; INV-A, pattern A invasive adenocarcinoma; INV-B, pattern B invasive adenocarcinoma; INV-C pattern C invasive adenocarcinoma.

Overall diagnostic reproducibility was moderate (κ=0.65, % agreement 91%). Degree of agreement was similar when observers were grouped according to years of experience (3 years or less versus more than 3 years of experience). Agreement in the distinction between in situ and invasive adenocarcinoma, regardless of the pattern, had a significantly lower level of agreement with κ=0.37 (% agreement 83%). Furthermore, the diagnosis of in situ vs invasive pattern A adenocarcinoma suffered from similar poor diagnostic agreement. The interobserver variation between these two diagnoses was calculated in the subset of 11 cases that were interpreted as either in situ or invasive pattern A adenocarcinoma by all reviewers; in other words, cases where none of the observers diagnosed destructive invasion. Agreement in this subset was slight (κ=0.23, % agreement 61%); higher agreement was seen among experienced pathologists.

Concordance in the diagnosis of destructive forms of invasive adenocarcinoma (pattern B vs C) was calculated in the subset of 39 cases that were interpreted as either pattern B or C by all reviewers (none diagnosed them as in situ or invasive pattern A adenocarcinoma). Agreement in this subset was also slight (κ=0.3, % agreement 70%) and also higher among experienced pathologists. Agreement in the diagnosis of pattern C only (versus all other patterns) was higher (κ=0.52, % agreement 78%).

Diagnostic reproducibility markedly improved when comparison was made between non-destructive forms of adenocarcinoma (in situ and pattern A invasive adenocarcinoma together) and destructively invasive adenocarcinoma (patterns B and C together), with κ=0.62 (% agreement 83%).

Distribution of diagnoses by level of interobserver agreement is displayed in Table 3. Examples of cases with high levels of agreement are depicted in Figures 3 and 4. Perfect agreement (9/9 reviewers) was seen in only 11 cases (11%), all destructively invasive (10 pattern C and 1 pattern B). Agreement by 8/9, 7/9, 6/9 and 5/9 reviewers was seen in 14 (15%), 26%, 16 (17%), 21 (23%) and 19 (20%) cases, respectively, for a total of 82 cases with ≥5/9 concordance (85% of the total). Among these concordant cases, most were destructively invasive: 57 (69%) were pattern B or C. Conversely, 25 (30%) tumors had an agreement diagnosis of adenocarcinoma in situ or pattern A invasive carcinoma.

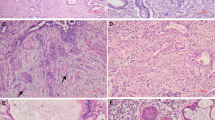

Non-destructive endocervical adenocarcinoma with high agreement on pattern diagnosis among observers (≥8/9). (a, b) Adenocarcinoma in situ: neoplastic glands are confined to the surface and have a lobulated distribution. (c, d) Pattern A invasive adenocarcinoma: glandular proliferation is more irregular and crowded; there is no destructive invasion. (e, f) Pattern A invasive adenocarcinoma: glandular growth is superficial, but the markedly increased glandular density and less defined lobulated architecture are indicative of non-destructive invasion. Atypical cytomorphology and mitotic activity is observed on high power magnification (inserts).

Destructively invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma with high agreement on pattern diagnosis among observers (≥8/9). (a) Pattern B invasive adenocarcinoma: irregular glands and tumor buds arising from well-demarcated (pattern A) glands; infiltrative glands appear fragmented and contain acute inflammation. (b, c) Pattern B invasive adenocarcinoma: deeply invasive tumor, mostly composed of well-demarcated glands but with focal desmoplasia and irregular, infiltrative glands, best seen at high power magnification. (d) Pattern C invasive adenocarcinoma: diffusely destructive invasion with markedly complex and irregular glands with cribriform and papillary architectural patterns. (e, f) Pattern C invasive adenocarcinoma: elongated and angulated glands in a desmoplastic stroma; tumor buds and individual cells are present at the tumor edge; lymphatic vascular invasion is also observed.

Consensus diagnosis, defined as the same pattern interpretation given by at least five reviewers, was not achieved in 14 cases (15% of the total). Representative images of these difficult cases are displayed in Figures 5, 6, 7. Several confounding features were observed in these cases, including exophytic papillary growth in part of the tumor, prominent periglandular chronic inflammation and stromal changes equivocal for desmoplastic reaction, glandular architecture difficult to classify as destructively invasive and reactive stromal change surrounding benign endocervical glands.

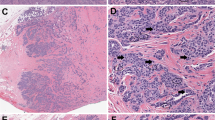

Non-destructive endocervical adenocarcinoma with poor agreement (<5/9 observers) on in situ versus invasive adenocarcinoma classified by pattern. (a) Endocervical adenocarcinoma with very low volume of neoplasm in the form of lobulated, round glands, in keeping with adenocarcinoma in situ; location away from the surface and slight loss of architecture raise concern for pattern A invasion. (b–f) Endocervical adenocarcinoma in the background of a prominent benign endocervical mucosa representing more than half of the cervical thickness; neoplasm is within the landmarks of the benign endocervix, but displays marked glandular density and focal cribriforming, highly suspicious for a pattern A invasive lesion. In these uncertain situations where consensus cannot be reached, the term endocervical adenocarcinoma with non-destructive growth can be considered.

Endocervical adenocarcinoma with poor agreement (<5/9 observers) on non-destructive versus destructive growth patterns. (a, b) The glandular density and irregular distribution are in keeping with invasion. Tumor was interpreted as pattern A by some reviewers; for others, the presence of glandular confluence raised the possibility of a pattern C. (c, d) Adenocarcinoma with exophytic papillary growth. Once surface papillary areas were excluded, there was disagreement in classifying areas of high glandular crowding and complexity as non-destructive or destructive invasion. (e, f) Adenocarcinoma with round well-demarcated glands consistent with pattern A, but with a slightly cellular and reactive stroma interpreted as desmoplasia by some reviewers (hence prompting classification as pattern B).

Invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma with poor agreement (<5/9 observers) on focal versus diffuse destructive patterns. (a–c) Adenocarcinoma with a markedly inflamed and reactive stroma. Although infiltrative invasion was diagnosed by all observers, the presence of inflammation precluded uniform determination of its extent, leading some observers to classify this pattern as B and others as C. (d–f) Focal destructive stromal invasion, in the form of irregular budding glands, was uniformly recorded. Nonetheless, the overall gland architecture was interpreted as diffusely destructive (angulated, elongated glands, pattern C) by some reviewers and as non-destructive (pattern A) by others.

Interobserver Agreement: Depth of Tumor Invasion

Estimation of the depth of tumor invasion in millimeters showed excellent reproducibility, superior to that of the pattern-based classification (ICC 0.82, 95% confidence interval 0.77–0.87). Agreement was comparable after grouping observers by years of experience (see Table 2 and Figure 2).

To determine the repercussion of the differences in depth of invasion measurement in pathologic staging, a hypothetical tumor stage was determined based on the depth of invasion provided by each reviewer following FIGO and AJCC tumor classifications. It is important to note that this stage calculation was done as part of the interobserver reproducibility analysis, and does not necessarily reflect the real tumor stage of the subjects included in the study (outlined below). Distribution of tumor stage by level of interobserver agreement is displayed in Table 4. Perfect agreement in pathologic tumor stage (9/9 reviewers) was seen in 20 cases (21%); among this subset, 15 cases were stage IB, 4 were stage IA2 and 1 was stage IA1. In the remaining 76 cases (79%), depth of invasion measurement from at least one reviewer was different enough to change the FIGO stage. Stage agreement by 8/9, 7/9, 6/9 and 5/9 reviewers was seen in 12 (12%), 24 (25%), 18 (19%) and 20 (21%) cases, respectively. Among the 94/96 cases with ≥5/9 concordance (98% of the total), 13 (14%) were classified as adenocarcinoma in situ, 29 (31%) as stage IA1, 25 (26%) as stage IA2 and 27 (29%) as stage IB invasive adenocarcinomas.

Clinical and Pathologic Features and Their Correlation with Pattern-Based Classification Agreement

Clinical and pathologic characteristics are displayed in Table 5. Median patient age was 42 years (range 25–67). Clinical follow-up was available in 82 subjects, 14 originally diagnosed as in situ and 68 as invasive adenocarcinoma. Follow-up interval after the immediate post-operative period ranged from 2.5 to 126 months (median 35 months). All 14 subjects with an initial diagnosis of adenocarcinoma in situ were alive with no evidence of disease. Similarly, most subjects diagnosed with invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma had no evidence of disease (65 subjects, 95%). One patient died due to other causes. Adverse outcome due to adenocarcinoma was documented in only two subjects: one died of disease and the other presented with pelvic and abdominal tumor recurrence. The tumors from these two subjects were classified as invasive pattern C by all nine pathologists (see Table 5).

Sixty-nine out of seventy-eight subjects (88%) with a clinical diagnosis of invasive adenocarcinoma underwent pelvic lymphadenectomy at the time of surgery. Number of lymph nodes removed ranged from 1 to 33 (median 13 lymph nodes). All subjects had negative lymph nodes, except for one (1%). Nodal spread in the latter was identified in 1 out of 23 lymph nodes. Tumor was classified as destructively invasive by all reviewers; there was, however, lack of consensus between focal versus diffuse destructive invasion (classified as pattern B by five reviewers and pattern C by four reviewers).

FIGO stage was available in 76 tumors clinically diagnosed as invasive. The majority (73 subjects, 96%) were early stage (FIGO stage I). One patient had parametrial involvement (stage IIB); tumor in this case was classified as pattern C by all nine reviewers. Another subject had ovarian metastases at the time of surgery (stage IVB); her tumor was classified as destructively invasive by all reviewers (pattern B by six reviewers and C by three). The last subject was stage IIIB based on the regional nodal involvement (described above).

Discussion

In current practice, staging and management recommendations for cervical cancer are based mainly on tumor stage. Stage IA1 invasive adenocarcinoma has an excellent prognosis even after conservative treatment (cone or simple hysterectomy) instead of the traditional radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy.12, 13, 14 In addition, there is evidence that tumors larger than stage IA1 with no lymphovascular space invasion or nodal involvement are associated with a favorable prognosis.15, 16 Indeed, most subjects in our cohort had an uneventful course at follow-up. Thus, there is a need to refine the staging and management approaches to invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma, avoiding excessive and unnecessary treatment for most patients while identifying subjects at the greatest risk of an adverse outcome.

The recently proposed pattern-based classification approach appears to be a promising tool to identify patients with minimal risk for adverse outcomes who will benefit from more conservative treatments. Most cases in our cohort were destructively invasive by consensus (27% as pattern B and 43% as pattern C) whereas 15% had a consensus diagnosis of pattern A adenocarcinoma. It is important to note that previous studies reported a similar case distribution: 12–21% for pattern A, 17–36% for pattern B and 53–71% for pattern C.3, 4, 5

Reproducibility of the pattern-based classification appears to be acceptable following a recent study by Paquette et al,6 which reports an overall consensus of 50%. In their study, Kappa values of pairwise pathologist agreements for the three-tier system ranged from fair (κ=0.24) to almost perfect agreement (κ=0.84). Interestingly, pairwise Kappa agreement improved when using a two-tier system (pattern A versus patterns B+C). Our study confirms this observation: reproducibility was the highest when grouping non-destructive and destructively invasive forms of adenocarcinoma (κ=0.62). Full (4/4) and partial (at least 3/4) agreement was attained in 50 and 77% of cases in the study by Paquette et al. Full agreement in our study was lower (11%), likely due to the higher number of reviewers involved; however, our rate of consensus agreement was comparable (85%). Importantly, our study incorporates important aspects not thoroughly evaluated in previous studies: we included adenocarcinoma in situ in our analysis, as well as depth of invasion. We were also able to compare diagnostic agreement according to the pathologist’s experience, which seems to have a minor role, if any, in diagnostic agreement. Although reproducibility of certain variables was higher among experienced pathologists, rates of concordance of the overall pattern classification, depth of invasion and distinction between in situ and invasive carcinomas were similar between experienced and relatively inexperienced pathologists.

Distinction between in situ and invasive adenocarcinoma is a common diagnostic challenge in gynecologic pathology. Certain morphologic patterns have been classically described as indicative of early stromal invasion, including small buds of cells, infiltrative finger-like processes, stromal reaction in the form of edema, desmoplasia or inflammation and complex glandular architectural patterns with cribriform or solid appearance.17, 18 Other helpful features have also been reported, such as neoplastic gland extension below the deepest normal endocervical gland landmark and close proximity to thick blood vessels.18, 19 Although these criteria are clearly outlined in the literature, uncertainty between invasive and in situ adenocarcinoma remains in approximately 10–20% of patients.7, 17 Indeed, our study showed poor interobserver agreement in the distinction between adenocarcinoma in situ and invasive adenocarcinoma (κ=0.37). This poor reproducibility contrasts with that of other organs, where the distinction between in situ and invasive carcinoma is more easily achieved using morphologic landmarks and immunohistochemical testing (for instance, myoepithelial markers in breast and prostate glandular lesions).

Diagnosis of non-destructive stromal invasion (pattern A adenocarcinoma) also suffered from considerable interobserver variation, and distinction from adenocarcinoma in situ was poorly reproducible. It is important to note that this ICC calculation was based only on cases classified as either adenocarcinoma in situ or invasive pattern A by the reviewers; tumors classified as pattern B or C by any observer were not included. This resulted in a smaller sample and a wider 95% confidence interval for this calculation.

In the context of our current knowledge on the behavior of invasive adenocarcinomas classified by pattern, re-addressing the reproducibility of the distinction between in situ and invasive carcinoma becomes important. Diagnosis of invasive carcinoma is clinically relevant when invasion is destructive, given the documented risk of nodal spread and adverse outcomes associated with it. Indeed, all subjects in our cohort with adverse features or outcome (advanced stage, lymph-node involvement, recurrence or death due to tumor) had tumors classified as either pattern B or C by all pathologists. Pattern A invasive adenocarcinoma is a diagnosis with low interobserver reproducibility compared with destructively invasive patterns. As this pattern carries a negligible risk of nodal spread and tumor recurrence, discriminating between in situ and pattern A invasive adenocarcinoma seems to be a clinically irrelevant endeavor. Therefore, in instances where such distinction is difficult and there is no consensus among colleagues, the term Endocervical Adenocarcinoma with Non-destructive Growth can be considered, followed by an explanatory comment. Avoiding denominating these difficult cases as invasive seems prudent since it will likely facilitate introducing more appropriate conservative therapies and follow-up (see Figure 8).

Classification of endocervical adenocarcinoma of usual (endocervical) type incorporating a pattern-based approach. In situ and pattern A invasive lesions can be grouped as Endocervical Adenocarcinomas with Non-destructive Growth, which have excellent prognosis and nil risk for nodal spread. When destructive invasion has been excluded, but there is difficulty in distinguishing between in situ and pattern A, avoiding the term ‘invasive’ should be contemplated. These cases are potentially amenable to conservative management. In contrast, destructive forms of neoplastic growth, either focal (pattern B) or diffuse (pattern C), are associated with low but significant rates of nodal spread and adverse outcome. Therefore, classification as destructive invasive adenocarcinoma and consideration for more aggressive treatment is warranted. Further validation of the prognostic significance of the pattern-based classification and proposed grouping is necessary.

Identification of destructive invasion showed acceptable interobserver reproducibility in our study. However, differentiation between patterns B and C showed only slight agreement. It is worth noting that this calculation was not based on our entire cohort but only a subset, resulting in a wider 95% confidence interval. Pattern C invasive adenocarcinomas have a significantly higher risk of nodal metastases compared with pattern B lesions. The latter, nonetheless, have a small but significant risk of nodal spread, advanced stage and poor outcome. This, in addition to the lack of high interobserver agreement, precludes at this point recommending conservative management for pattern B tumors. Unfortunately, a significant number of subjects with destructive forms of invasive adenocarcinoma will still receive radical treatment modalities that are likely unnecessary. Indeed, in our study not only all patients with endocervical adenocarcinoma with non-destructive growth, but also the majority of those with destructively invasive tumors, had an uneventful follow-up. Thus, a pattern-based approach helps to identify only a subset of low-risk cancers, and it is imperative to continue searching for morphologic features and/or ancillary (immunohistochemical, molecular) tools that separate lesions that will behave aggressively from those that will not.

The low rate of adverse events in our series precludes definitive conclusions regarding the prognostic significance of the pattern-based classification and our proposed binary approach, and independent validation of their prognostic value is still necessary. Achieving the necessary sample size and number of adverse events for such validation may be challenging. For instance, the classification relies on excision material (cone, hysterectomy), usually obtained in early-stage tumors that will likely behave indolently; conversely, patients with advanced tumor stage at presentation (and higher chances of adverse outcome) may not be offered primary surgical treatment in most centers.

As a defining feature of stage I invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma, depth of invasion is important to assess the likelihood of recurrence and guide management. Tumors with less than 3 mm of depth of invasion (FIGO stage IA1) have very low rates of lymph-node metastases, parametrial spread20, 21 and recurrence14, 22 compared with larger tumors confined to the cervix (stages IA2, IB1 and IB2). Likewise, reported rates of lymph-node metastatic involvement for lesions ≤5 mm of depth are extremely low, ranging from 0 to 2%.8, 12, 13 Overall survival is high, 98.7%,8, 12 and rates of tumor recurrence are low, 0–3.4%.8, 13 In addition, depth of invasion also correlates with overall survival.23 Thus, determination of the depth of invasion metric is critical.

Measurement of the depth of invasion can be difficult in routine practice. According to our results, however, difficulties do not seem to result into poor interobserver agreement; to the contrary, reproducibility of this parameter was high among observers, superior to that of the pattern-based classification. It is worth noting that assessment of the variable was based on examination of only two histologic sections per case, which may contribute to the excellent interobserver agreement. Nevertheless, given the high level of diagnostic reproducibility found in our study, the depth of invasion metric should continue to be part of the routine histopathologic analysis and staging of endocervical adenocarcinoma. Despite its high level of agreement, depth of invasion calculation by pathologists was not 100% concordant. This was evidenced by the fact that, in 79% of our cases, the measurement by at least one out of the nine pathologists was different enough to produce a different FIGO stage. Obviously, discrepancies decreased when less than perfect concordance (five or more out of the nine reviewers) was accepted. Therefore, establishing a consensus with colleagues on important metrics such as depth of invasion is recommended in routine practice, particularly if the measurement by an individual pathologist approaches thresholds for upstaging/downstaging (for instance, 3 and 5 mm for depth of tumor invasion and 7 mm for horizontal spread, which mark the difference between FIGO stages IA1, IA2 and IB).

In summary, the distinction between in situ and invasive adenocarcinoma is poorly reproducible. From an interobserver agreement perspective, the pattern-based classification is best at distinguishing destructive patterns of invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma (patterns B and C) which carry a risk for nodal metastases, from non-destructive patterns. Agreement may improve if awareness of the pattern-based classification increases and pathologists start assessing the pattern of invasion on a routine basis. Reproducibility in the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma in situ versus pattern A invasive adenocarcinoma was poor. Given the nil risk of nodal spread in both instances, the term ‘Endocervical Adenocarcinoma with Non-destructive Growth’ is recommended when the distinction between the two is difficult, after excluding destructive patterns of invasion. This change in the diagnostic approach and nomenclature is, in our opinion, prudent and complimentary to the increasing shift toward a more conservative management of patients with low-risk forms of cervical glandular neoplasia. Estimation of depth of tumor invasion was highly reproducible among pathologists; thus, the pattern-based classification can certainly complement, but should not replace, the depth of invasion metric. Owing to the inherent interobserver variation in both pattern designation and depth of invasion measurement, consensus interpretation with colleagues should be routinely pursued.

References

Pecorelli S, Zigliani L, Odicino F . Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;105:107–108.

Diaz De Vivar A, Roma AA, Park KJ et al. Invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma: proposal for a new pattern-based classification system with significant clinical implications: a multi-institutional study. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2013;32:592–601.

Roma AA, Diaz De Vivar A, Park KJ et al. Invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma: a new pattern-based classification system with important clinical significance. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:667–672.

Jeffus SK, Quick CM, Stolnicu S et al. Tumor growth pattern can predict nodal metastasis: a study of 130 cases of endocervical adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 28:292A.

Djordjevic B, Parra-Herran C . Application of a pattern-based classification system for invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma in cervical biopsy, cone and loop electrosurgical excision (LEEP) material: pattern on cone and LEEP is predictive of pattern in the overall tumor. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2015:1–11; e-pub ahead of print; PMID:26630232.

Paquette C, Jeffus SK, Quick CM et al. Interobserver variability in the application of a proposed histologic subclassification of endocervical adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:93–100.

Zaino RJ . Symposium part I: adenocarcinoma in situ, glandular dysplasia, and early invasive adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;21:314–326.

Ostör AG . Early invasive adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2000;19:29–38.

Fleiss J . Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull 1971;76:378–381.

Gwet K . Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability: The Definitive Guide to Measuring the Extent of Agreement Among Multiple Raters, 4th edn. Advanced Analytics LLC: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2014, pp 375–389.

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL . Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420–428.

Webb JC, Key CR, Qualls CR et al. Population-based study of microinvasive adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:701–706.

Balega J, Michael H, Hurteau J et al. The risk of nodal metastasis in early adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2004;14:104–109.

Ceballos KM, Shaw D, Daya D . Microinvasive cervical adenocarcinoma (FIGO stage 1A tumors): results of surgical staging and outcome analysis. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:370–374.

Baalbergen A, Ewing-Graham PC, Hop WCJ et al. Prognostic factors in adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol 2004;92:262–267.

Baalbergen A, Smedts F, Helmerhorst TJM . Conservative therapy in microinvasive adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix is justified: an analysis of 59 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2011;21:1640–1645.

McCluggage WG . Endocervical glandular lesions: controversial aspects and ancillary techniques. J Clin Pathol 2003;56:164–173.

Mutter G, Pratt J . Pathology of the Female Reproductive Tract, 3rd edn. Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014, pp 258–259.

Wheeler DT, Kurman RJ . The relationship of glands to thick-wall blood vessels as a marker of invasion in endocervical adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2005;24:125–130.

Reynolds EA, Tierney K, Keeney GL et al. Analysis of outcomes of microinvasive adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix by treatment type. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1150–1157.

Poynor EA, Marshall D, Sonoda Y et al. Clinicopathologic features of early adenocarcinoma of the cervix initially managed with cervical conization. Gynecol Oncol 2006;103:960–965.

Teshima S, Shimosato Y, Kishi K et al. Early stage adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Histopathologic analysis with consideration of histogenesis. Cancer 1985;56:167–172.

Berek JS, Hacker NF, Fu YS et al. Adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: histologic variables associated with lymph node metastasis and survival. Obstet Gynecol 1985;65:46–52.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parra-Herran, C., Taljaard, M., Djordjevic, B. et al. Pattern-based classification of invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma, depth of invasion measurement and distinction from adenocarcinoma in situ: interobserver variation among gynecologic pathologists. Mod Pathol 29, 879–892 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.86

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.86

This article is cited by

-

Silva cumulative score and its relationship with prognosis in Endocervical adenocarcinoma

BMC Cancer (2022)

-

Aktuelle WHO-Klassifikation des weiblichen Genitale

Der Pathologe (2021)

-

The pattern is the issue: recent advances in adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix

Virchows Archiv (2018)

-

Genomic abnormalities in invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma correlate with pattern of invasion: biologic and clinical implications

Modern Pathology (2017)