Abstract

Autoantibody formation directed against phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R)1 is the underlying etiology in most cases of primary membranous glomerulopathy. This new understanding of the pathogenesis of primary membranous is in the process of transforming the way the disease is diagnosed. We validated an indirect immunofluorescence assay to examine PLA2R1 in renal biopsies utilizing a commercially available antibody and standard indirect immunofluorescence. Using this assay, we examined a total of 165 cases of membranous glomerulopathy including 85 primary and 80 secondary. We found tissue staining for PLA2R1 to have a sensitivity of 75% (95% CI 65−84%) and a specificity of 83% (95% CI 72−90%) for primary membranous glomerulopathy. Hepatitis C virus was the secondary etiology with the most number of cases staining positive for PLA2R1 (7/11, 64%) followed by sarcoidosis (3/4, 75%) and neoplasm (3/12, 25%). Autoimmune etiologies showed rare PLA2R1-positive staining (1/46, 2%). All cases of secondary membranous glomerulopathy with positive PLA2R1 showed IgG4-predominant staining, which is typically associated with primary membranous glomerulopathy. This IgG4 predominance raises the possibility that these cases are more pathogenically related to primary membranous glomerulopathy than secondary. We present the largest case series to date examining PLA2R1 involvement in membranous glomerulopathy utilizing a technique that is readily adoptable by most renal pathology laboratories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Membranous glomerulopathy is a morphological pattern of glomerular immune complex deposition characterized by widespread subepithelial deposits. There are numerous etiologies for this deposition including autoimmune disease, infection, and cancer. When one of these known etiologies is present the disease is termed ‘secondary’. Those cases in which none of these systemic diseases are present have traditionally been termed ‘primary’ or ‘idiopathic’ membranous glomerulopathy. It has long been suspected that the pathogenesis of primary membranous glomerulopathy is related to autoantibodies reacting with a podocyte antigen, resulting in in situ formation of immune complexes.1 The recent work of Beck et al2 confirmed this hypothesis by showing that most cases of primary membranous glomerulopathy are the result of an autoimmune disease targeting the podocyte antigen phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R1).

The recognition of PLA2R1 as the target antigen in patients with membranous glomerulopathy has made it possible to design serological assays that hold promise for the diagnosis and monitoring of membranous glomerulopathy. The presence of PLA2R1 antibodies in the serum has been shown in previous reports to have a sensitivity of 70−82% and a specificity of 89−100%, for the detection of primary membranous glomerulopathy.2, 3 Despite the fact that PLA2R1 serological tests have been described in multiple reports, there are limited data available on the sensitivity and specificity of PLA2R1 staining in the renal tissue. Further, most of the reports to date of immunofluorescence testing for PLA2R1 in tissue use confocal microscopy that is not readily available in most pathology laboratories. One of the largest case series to date detailed PLA2R1 staining in 42 cases of primary membranous glomerulopathy and showed that tissue staining was more sensitive for detection of PLA2R1-associated membranous glomerulopathy than serological testing with sensitivities of 74% and 57%, respectively. No data for specificity were available as only primary cases were included in this study.4 Another recent report showed better correlation between tissue staining and the serological test, though no sensitivity or specificity data were reported.5

We determined the sensitivity and specificity of PLA2R1 tissue staining for detecting primary membranous glomerulopathy in a large renal biopsy series. This is the largest series to date examining PLA2R1 involvement in membranous glomerulopathy. To perform this study, we first validated an immunofluorescence assay for PLA2R1 testing in renal biopsies using a commercially available antibody and standard immunofluorescence.

Materials and methods

Patient Selection

The database at Nephropath was searched for cases of membranous glomerulopathy in adults (over age 18) from 2005 to present. Cases were designated as secondary membranous glomerulopathy if they had an active disease that is a known secondary etiology of membranous glomerulopathy and designated as primary after exclusion of known secondary etiologies. Inclusion criteria for primary membranous glomerulopathy included negative serological testing for ANA, ANCA, HCV, HBV, HIV, RPR as well as a negative clinical evaluation for any neoplasm. Neoplasm-associated membranous glomerulopathy only included patients who were known to have the neoplasm at the time of the biopsy for membranous glomerulopathy. Specifically, patients who had a remote history of a neoplasm status post treatment and deemed to be in remission were not included in this group. Cases without a known workup for secondary etiologies were excluded from the study. A total of 165 biopsies were identified in which there was the necessary clinical information available for inclusion as well as adequate tissue remaining in the paraffin block. This included 80 cases of secondary membranous glomerulopathy and 85 of primary. All cases had light and immunofluorescence results. Additional clinical and biopsy data, including electron microscopy findings, 24 h urine protein and serum creatinine were incorporated, when available.

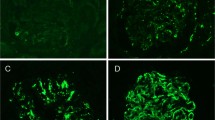

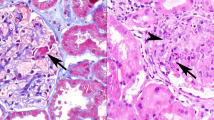

Renal biopsy processing techniques

Standard renal biopsy processing techniques were used including light, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy.6, 7 All light microscopy samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Jones methenamine silver, Masson trichrome, and periodic acid-Schiff reagent. All direct immunofluorescence sections were cut at 5 μm and reacted with fluorescein-tagged polyclonal rabbit anti-human antibodies to IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, C1q, fibrinogen, and κ-, and λ-light chains (Dako, Carpenteria, CA, USA) for 1 h, rinsed, and a cover slip applied using aqueous mounting media. Select cases were stained for fluorescein-tagged polyclonal mouse anti-human antibodies to IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). For electron microscopy, thin sections were examined in a Jeol JEM-1011 electron microscope (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan). Photomicrographs were routinely taken at × 5000, × 12 000, and × 20 000 magnifications. Electron photomicrographs were used to stage the cases of membranous glomerulopathy according to the classification of Ehrenreich and Churg.8 Electron photomicrographs were also utilized to identify mesangial and subendothelial deposits. For this report, the term ‘mesangial deposits’ refers to deep mesangial deposits within the mesangial matrix and internal to an identifiable paramesangial basement membrane.9

PLA2R1 Immunofluorescence

The PLA2R1 immunofluorescence staining procedure is briefly outlined in Box 1. PLA2R1 was detected in paraffin-embedded sections using rabbit polyclonal anti-PLA2R1 antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) at a dilution of 1:50 followed by highly cross-adsorbed Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1:100. Each case was run with a positive and negative (secondary antibody only) control. The stain was evaluated by standard immunofluorescence microscopy using a Leica L5 filtercube. It was judged to be positive if there was positive granular capillary loop staining in the glomeruli and negative if there was no staining in glomeruli. Each stain was given a score on a scale of 0−3+. Twenty renal biopsies without membranous glomerulopathy were also evaluated by this staining procedure including normal kidney (n=5), IgA nephropathy (n=3), fibrillary glomerulopathy (n=2), type 1 MPGN (n=2), minimal change disease (n=3), cryoglobulinemic-associated glomerulonephritis (n=2), post infectious glomerulonephritis (n=2), and proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits (n=1). All PLA2R1 stains were evaluated by at least two renal pathologists.

Results

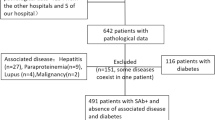

The biopsies were divided by etiology and the clinical and morphological details are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Cases of membranous glomerulopathy showed either granular-positive staining for PLA2R1 in the same pattern as the IgG or were completely negative (Figure 1). There was no PLA2R1 staining in the glomeruli of any of the 20 biopsies without membranous glomerulopathy. PLA2R1 was positive in 64/85 cases of primary membranous glomerulopathy and 14/80 cases of secondary membranous glomerulopathy (Table 2). The sensitivity and specificity of PLA2R1 for detection of primary membranous glomerulopathy was 75% (95% CI 65−84%) and 83% (95% CI 72−90%), respectively, with a positive likelihood ratio of 4.3 (95% CI 2.6−7). There were a total of 78 cases that stained positive for PLA2R1 including 44 that were scored 3+, 28 scored 2+, and 6 scored 1+ (scale 0−3+).

Phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R1 staining in membranous glomerulopathy. (a) Granular staining for PLA2R1 along glomerular basement membranes in a patient with idiopathic membranous glomerulopathy (indirect immunofluorescence; original magnification × 400). (b) Glomerulus from patient with hepatitis B virus-associated membranous glomerulopathy is completely negative for PLA2R1 (indirect immunofluorescence; original magnification × 400).

Most etiological categories of secondary membranous glomerulopathy had only rare cases with PLA2R1 staining with two notable exceptions. Sixty-four percent of cases of HCV-associated membranous glomerulopathy and 75% of sarcoidosis-associated membranous glomerulopathy were PLA2R1 positive. The neoplasm-associated group had the third highest rate with positive PLA2R1 staining present in 3 of 12 cases (25%). The neoplasm-associated cases with positive PLA2R1 included one case each of urothelial, colonic, and thyroid carcinoma. The cases with negative staining included three cases of pulmonary carcinoma, one case of metastatic prostate carcinoma, one case of breast carcinoma, one case of ovarian carcinoma, two cases of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and one case of the myeloproliferative disorder essential thrombocythemia.

IgG subtype evaluation was performed in all PLA2R1-positive cases with a known secondary etiology as well as in cases of primary membranous glomerulopathy with negative staining for PLA2R1, if adequate tissue was available for staining. There were a total of six cases with PLA2R1-positive secondary membranous glomerulopathy that had tissue available for staining and all were IgG4 predominant (Table 3). A total of 17 PLA2R1-negative idiopathic membranous glomerulopathy also had tissue available for IgG subtype analysis. Ten of these 17 cases were IgG4 predominant or co-dominant (Table 3).

The morphological findings examined in all cases included the pattern of deposition (global versus segmental), immunofluorescence staining pattern, evaluation for subendothelial and mesangial deposits, and stage of membranous glomerulopathy. A total of eight segmental membranous glomerulopathy cases were present in the study including two idiopathic and six secondary, all of which were negative for PLA2R1 staining. Five idiopathic and no secondary cases showed light chain restriction (all κ) in the membranous deposits, of which one proved to be PLA2R1 positive and the remaining were negative. Subendothelial deposits were present in a total of 16 cases, all of which were secondary. None of these cases with subendothelial deposits were positive for PLA2R1. Mesangial deposits were present in a total of 86 cases including 25 idiopathic and 61 secondary. Twenty-five of these cases with mesangial deposits were positive for PLA2R1 including 19 idiopathic and 6 secondary cases. There were a total of 10 cases with full-house staining, of which none showed positive staining on PLA2R1. Among the idiopathic cases, there was no statistically significant difference in the stage between PLA2R1-positive and -negative staining cases (P=0.275).

Discussion

Membranous glomerulopathy is one of the most common etiologies of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in adults and leads to end-stage renal disease in up to one third of patients.10, 11 The clinical treatment of this disease hinges upon whether the disease is determined to be primary or secondary. The treatment of primary membranous glomerulopathy commonly utilizes immunosuppression regimens, which are frequently associated with significant treatment complications, whereas secondary membranous glomerulopathy treatment is targeted toward the underlying disease.12 This distinction between primary and secondary membranous glomerulopathy is ultimately determined on clinical grounds after a thorough evaluation. However, there are findings on the renal biopsy that, while not specific, are suggestive of one over the other and typically factor into the overall determination.

The discovery of PLA2R1 as the target antigen in the majority of idiopathic membranous glomerulopathy has transformed our understanding of this disease. Early reports indicate that serological assays for disease detection will prove useful for diagnosis and disease monitoring.2, 13, 14 Although staining for PLA2R1 in renal biopsies is recommended,15 there is limited data available for use in interpretation of the results available. To our knowledge, ours is the largest series to date examining PLA2R1 involvement in membranous glomerulopathy and it is the first large case series in human renal biopsies to detail both the sensitivity and specificity of PLA2R1 for primary membranous glomerulopathy.

The PLA2R1 immunofluorescence assay described in this study is simple to interpret for renal pathologists as it is scored in an identical way to the IgG immunofluorescence stain. The majority of cases show very strong staining when positive and there is virtually no background staining. Confocal microscopy has been utilized for PLA2R1 staining in previous reports to distinguish normal podocyte staining from staining in the immune deposits.2, 13 However, standard immunofluorescence is suitable when using the technique described herein as there is no detectable podocyte staining in normal or diseased glomeruli. The reason for this absence of podocyte staining is unclear. Likely, PLA2R1 is present at low levels in normal glomeruli and thus below the level of detection. Another possibility is that the target epitope of the antibody is not available for binding in the protein’s normal conformational state but becomes available in membranous glomerulopathy. Regardless of the mechanism, it is clear that the staining is specific for membranous glomerulopathy and the sensitivity is comparable to that which has been previously reported.2, 4

Morphological findings commonly associated with secondary membranous glomerulopathy include the presence of mesangial deposits, segmental involvement of glomeruli by deposits, and a ‘full-house’ staining pattern on immunofluorescence.9, 16, 17, 18 The most common of these findings in our series was that of mesangial immune complex deposition. Approximately 29% of cases with mesangial deposits showed positive staining by PLA2R1. Among the 78 PLA2R1-positive cases, there was a slightly higher percentage of secondary cases with mesangial deposits (43%) than primary (30%). However, this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.29). Thus, the presence of mesangial deposits in PLA2R1-positive cases is not a useful marker to separate primary from secondary causes. All eight of the cases of segmental membranous glomerulopathy were found to be PLA2R1 negative confirming previous work, suggesting that this is not merely an early form of primary membranous glomerulopathy but rather an entity distinct from global membranous glomerulopathy.19 The findings of ‘full house’ staining and subendothelial deposits are highly specific for secondary membranous glomerulopathy as all cases with these findings had a known secondary etiology and were negative for PLA2R1.

The vast majority of cases of membranous glomerulopathy show near-equal staining intensity for light chains. However, there are rare cases with light chain restriction, usually κ. These cases have more recently been included within the spectrum of ‘proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits’ (Nasr Disease).20 The majority of the reported cases are idiopathic in nature without a known secondary lymphoproliferative disorder.21 There is, however, one report of this form of membranous glomerulopathy in the setting of lymphoma.22 We had a total of five cases of membranous glomerulopathy with light chain restriction in our series, as there were no secondary etiologies identified clinically (including lymphoproliferative disorder) all of these cases were classified as idiopathic. Only one of these five cases showed positive staining by PLA2R1 (Table 3). This significance of light chain restriction in membranous glomerulopathy is uncertain at this time. Although it is prudent to exclude lymphoproliferative disorders clinically when this finding is present, in most cases it is not a marker of a known secondary etiology.

IgG subtype analysis has been studied for the detection of primary membranous glomerulopathy and is currently used in many renal pathology laboratories for this purpose. IgG4-predominant staining is associated with primary membranous glomerulopathy, whereas IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3 predominate in the deposits of secondary membranous glomerulopathy.3, 23, 24, 25, 26 However, the sensitivity and specificity of various IgG subtype staining patterns for primary membranous glomerulopathy has not been well documented. We examined the IgG subtypes in cases of secondary membranous with positive PLA2R1 to determine whether they would follow the pattern of idiopathic membranous glomerulopathy with IgG4-predominant staining or that of secondary membranous glomerulopathy with IgG1−3 dominant staining. The most common secondary causes of membranous glomerulopathy to show positive PLA2R1 staining were HCV, sarcoidosis, and neoplasms. The fact that all six cases with available tissue showed IgG4-predominant staining, suggests that these cases of membranous glomerulopathy may be more pathogenically related to primary membranous glomerulopathy than secondary. It also raises the question of whether these underlying ‘secondary’ causes are truly implicated in the etiology of the membranous glomerulopathy or if they are merely coincidental unrelated occurrences. IgG subtype analysis was also performed on cases of membranous glomerulopathy, which were clinically idiopathic but did not show PLA2R1 staining. Interestingly, 7/17 cases did not show IgG4 predominance in deposits, further suggesting that there could be an undetected secondary etiology driving the disease.

The specificity of PLA2R1 in detecting ‘primary’ membranous glomerulopathy is a point of controversy. Some have proposed that primary membranous glomerulopathy is characterized by PLA2R1 involvement and that evidence of PLA2R1 involvement in membranous glomerulopathy excludes secondary etiologies. If this is the case, the presence of an otherwise known secondary etiology in the setting of membranous glomerulopathy with positive PLA2R1 is by definition the chance occurrence of two diseases. Based on the current report and that of Qin et al,3 it is clear that PLA2R1-positive membranous glomerulopathy can occur in the setting of what would otherwise be considered a secondary etiology. This stands in contrast to the data of Hoxha et al,5 who report no secondary etiologies in cases with PLA2R1 staining. It should be noted, however, that Hoxha et al provided no detail as to what secondary etiologies were excluded. Although we recognize that secondary etiologies in the setting of PLA2R1-positive membranous glomerulopathy most likely represent the chance occurrence of two diseases, we believe it is premature at this point to definitively draw this conclusion. It is conceivable that the secondary etiology could be driving the disease process despite this PLA2R1 positivity and IgG4 predominance. Perhaps the inflammatory milieu present in these conditions triggers the onset of disease in susceptible individuals with membranous glomerulopathy risk alleles.27 It is also possible that PLA2R1 autoantibodies are the result of an aberrant expression of PLA2R1 epitopes by the tumor cells in neoplasm-associated membranous glomerulopathy or by the granulomas in sarcoidosis-associated membranous glomerulopathy. More studies are needed to determine the clinical significance of PLA2R1 antibodies in the setting of secondary membranous glomerulopathy, particularly whether or not secondary membranous glomerulopathy cases with positive PLA2R1 staining are less likely to resolve after treatment of the underlying disease than PLA2R1-negative cases.

We present the largest series of membranous glomerulopathy with PLA2R1 results to date and detail the sensitivity and specificity of an immunofluorescence assay that could be immediately adopted by the majority of renal pathology laboratories. PLA2R1 is a useful marker of primary membranous glomerulopathy with a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 83%.

References

Ronco P, Debiec H . Molecular pathomechanisms of membranous nephropathy: from Heymann nephritis to alloimmunization. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:1205–1213.

Beck LH, Bonegio RG, Lambeau G et al M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2009;361:11–21.

Qin W, Beck LH, Zeng C et al Anti-phospholipase A2 receptor antibody in membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:1137–1143.

Debiec H, Ronco P . PLA2R autoantibodies and PLA2R glomerular deposits in membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2011;364:689–690.

Hoxha E, Kneissler U, Stege G et al Enhanced expression of the M-type phospholipase A2 receptor in glomeruli correlates with serum receptor antibodies in primary membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2012;82:797–804.

Walker PD, Cavallo T, Bonsib SM . Practice guidelines for the renal biopsy. Mod Pathol 2004;17:1555–1563.

Walker PD . The renal biopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2009;133:181–188.

Ehrenreich T, Churg J . Pathology of membranous nephropathy. Pathol Annu 1968;2:145–186.

Jennette JC, Iskandar SS, Dalldorf FG . Pathologic differentiation between lupus and nonlupus membranous glomerulopathy. Kidney Int 1983;24:377–385.

Segal PE, Choi MJ . Recent advances and prognosis in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2012;19:114–119.

Nair R, Bell JM, Walker PD . Renal biopsy in patients aged 80 years and older. Am J Kidney Dis 2004;44:618–626.

McQuarrie EP, Stirling CM, Geddes CC . Idiopathic membranous nephropathy and nephrotic syndrome: outcome in the era of evidence-based therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:235–242.

Debiec H, Martin L, Jouanneau C et al Autoantibodies specific for the phospholipase A2 receptor in recurrent and De Novo membranous nephropathy. Am J Trans 2011;11:2144–2152.

Debiec H, Ronco P . Nephrotic syndrome: a new specific test for idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol 2011;7:496–498.

Glassock RJ . Attending rounds: an older patient with nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;7:665–670.

Markowitz GS . Membranous glomerulopathy: emphasis on secondary forms and disease variants. Adv Anat Pathol 2001;8:119–125.

Glassock RJ . Secondary membranous glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1992;7:64–71.

Honig C, Mouradian JA, Montoliu J et al Mesangial electron-dense deposits in membranous nephropathy. Lab Invest 1980;42:427–432.

Obana M, Nakanishi K, Sako M et al Segmental membranous glomerulonephritis in children: comparison with global membranous glomerulonephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;1:723–729.

Nasr SH, Satoskar A, Markowitz G et al Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:2055–2064.

Komatsuda A, Masai R, Ohtani H et al Monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disease associated with membranous features. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:3888–3894.

Evans DJ, Macanovic M, Dunn MJ et al Membranous glomerulonephritis associated with follicular B-cell lymphoma and subepithelial deposition of IgG1-κ paraprotein. Nephron Clin Pract 2003;93:112–118.

Doi T, Mayumi M, Kanatsu K et al Distribution of IgG subclasses in membranous nephropathy. Clin Exp Immunol 1984;58:57–62.

Ohtani H, Wakui H, Komatsuda A et al Distribution of glomerular IgG subclass deposits in malignancy-associated membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:574–579.

Haas M . IgG subclass deposits in glomeruli of lupus and nonlupus membranous nephropathies. Am J Kidney Dis 1994;23:358–364.

Kearney N, Podolak J, Matsumura L et al Patterns of IgG subclass deposits in membranous glomerulonephritis in renal allografts. Transplant Proc 2011;43:3743–3746.

Stanescu HC, Arcos-Burgos M, Medlar A et al Risk HLA-DQA1 and PLA2R1 alleles in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2011;364:616–626.

Acknowledgements

We thank Robert Yerton, Steve Strong, and Cindy Smith for their valuable technical aid as well as I-Shen Wen and Tina Priddy for their ever helpful administrative support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Larsen, C., Messias, N., Silva, F. et al. Determination of primary versus secondary membranous glomerulopathy utilizing phospholipase A2 receptor staining in renal biopsies. Mod Pathol 26, 709–715 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.207

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.207

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

PLA2R-positive membranous nephropathy in IgG4-related disease

BMC Nephrology (2024)

-

Lupus-like membranous nephropathy during the postpartum period expressing glomerular antigens exostosin 1/exostosin 2 and phospholipase A2 receptor: a case report

CEN Case Reports (2024)

-

The value of PLA2R antigen and IgG subclass staining relative to anti-PLA2R seropositivity in the differential diagnosis of membranous nephropathy

BMC Nephrology (2023)

-

Favorable outcome in PLA2R positive HBV-associated membranous nephropathy

BMC Nephrology (2022)

-

IgA nephropathy associated with anti-PLA2R antibody positive: a case report

International Urology and Nephrology (2022)