Abstract

Measured and calculated results are presented for the emission properties of a new class of emitters operating in the cavity quantum electrodynamics regime. The structures are based on high-finesse GaAs/AlAs micropillar cavities, each with an active medium consisting of a layer of InGaAs quantum dots (QDs) and the distinguishing feature of having a substantial fraction of spontaneous emission channeled into one cavity mode (high β-factor). This paper demonstrates that the usual criterion for lasing with a conventional (low β-factor) cavity, that is, a sharp non-linearity in the input–output curve accompanied by noticeable linewidth narrowing, has to be reinforced by the equal-time second-order photon autocorrelation function to confirm lasing. The paper also shows that the equal-time second-order photon autocorrelation function is useful for recognizing superradiance, a manifestation of the correlations possible in high-β microcavities operating with QDs. In terms of consolidating the collected data and identifying the physics underlying laser action, both theory and experiment suggest a sole dependence on intracavity photon number. Evidence for this assertion comes from all our measured and calculated data on emission coherence and fluctuation, for devices ranging from light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and cavity-enhanced LEDs to lasers, lying on the same two curves: one for linewidth narrowing versus intracavity photon number and the other for g(2)(0) versus intracavity photon number.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The question, ‘What is a laser?’ has been a long-standing subject of discussion1. For example, during the 1970s, there was much debate over whether the X-ray laser was really a ‘laser’ given the poor or non-existent resonator. Currently, the question is resurfacing for an entirely different reason. With micro- and nanocavities producing high Q-factors and close to complete channeling of all spontaneous emission into a single cavity mode ( ), cavity quantum electrodynamic (cQED) effects may be present to the extent that the concepts of lasing action and verification have to be reexamined2, 3, 4, 5.

), cavity quantum electrodynamic (cQED) effects may be present to the extent that the concepts of lasing action and verification have to be reexamined2, 3, 4, 5.

The development of low-threshold micro- and nanolasers has become an important interdisciplinary research topic in recent years, encompassing epitaxy growth and lithographic chemistry, spectroscopic and photon correlation measurements, as well as quantum optics and quantum electronics6, 7. Research has been conducted for multiple material systems, ranging from III–V and III-nitride compounds to silicon8. Even emerging two-dimensional materials have been applied as active media for nanolasers9. Cavity designs for photonic lattices, micropillars and plasmonic cavities embedding bulk, quantum-well and quantum-dot (QD) gain materials are being explored10, 11.

There is considerable activity focusing on high-β lasers because of the potential to exceed present limits on lasing threshold, modulation speeds and spatial footprint. Advances are being made in geometrical waveguiding and in enhancing performance by quantum optical effects, such as the Purcell effect12. The interest in using high-β cavities extends beyond lasers to light-emitting diodes (LEDs), for applications such as high-efficiency lighting, and to single-photon sources, for quantum information processing13, 14. In research applications, high-β emitters provide experimental platforms to study the intricate interplay between classical cavity-mode confinement and quantum optics15, 16, 17.

Along with the exciting progress achieved in device performance and in realizing application potential, there is a vivid debate on the precise definition and verification of lasing in high-β emitters181920212223. Particular controversy exists regarding the limiting regime involving the interesting prospect of thresholdless lasing24, 25. Indeed, with an increasing β-factor, it becomes more difficult to find a definitive transition in device output intensity from being dominated by spontaneous emission to being governed by stimulated emission. Such a transition has long been accepted as the characteristic signature of lasing.

Usually, lasing in a high-β emitter is claimed when there is noticeable linewidth narrowing (or coherence time increase) accompanied by an intensity output versus input curve (often with output in arbitrary units) that does not show a pronounced ‘S’ shape on a log–log plot26, 27, 28, 29, 30. In this paper, we reinforce earlier investigations indicating that these two pieces of information are insufficient proof for lasing19. We measure and model the excitation dependencies of the intensity, linewidth and second-order photon autocorrelation of emitters operating purely as LEDs, as lasers and as cavity-enhanced LEDs. The emitters consist of AlAs/GaAs micropillar cavities with InGaAs QD gain regions. Many of the devices show input–output curves and linewidth narrowing that satisfy the generally accepted criteria for lasing in high-β cavities. However, measurements of second-order photon autocorrelation indicate distinctly different statistical properties of the emitted photons.

Photon correlations have been largely ignored by the laser engineering community in regard to characterizing devices. In addition to the demanding time and equipment requirements, this measurement is unnecessary for emitters operating with conventional resonators. The customary lasing criterion is the appearance of a noticeable kink in a log–log plot of output versus input power. For further confirmation, one looks for a sharp increase in linewidth narrowing in the vicinity of the input–output jump. However, the abruptness of these signatures diminishes in high-β lasers, with the input–output jump disappearing altogether and the linewidth narrowing not approaching the Schawlow-Townes linewidth in the limit of 'thresholdless' lasing31, 32, 33, 34. This difference makes for much discussion when distinguishing between high-β lasing and the effects from nonlinearities (for example, from saturation or state filling) in a non-lasing, β<<1 emitter.

In contrast to laser engineering, the quantum optics community has long studied photon statistics, which are customarily gauged by the equal-time second-order photon autocorrelation function g(2)(0)19, 34, 35, 36. Specifically, when g(2)(0) reduces from 2 to 1, the emitted light transitions from spontaneous emission dominated to predominately stimulated emission. This change from thermal to coherent emission serves as a reliable indicator for lasing.

Following this introduction, we describe the experimental devices and setup for performing the systematic measurements of emission intensity, coherence and photon correlations, together with an overview of the theoretical approach to model the quantum optics of nanoemitters. Results are presented in the form of output intensity, emission linewidth and g(2)(0) versus optical pump power. The measured micropillar emitters have Q-factors varying from 8000 to 35 000 and β-factors from 0.2 to 0.4. In terms of the number of QDs within the entire inhomogeneously broadened distribution that interact with the radiation field, our simulations indicate a range from 5 to 40. Analyses of the experiments, using the cQED model, show a commonality among the devices in the form of a relationship between g(2)(0) and the intracavity photon number in the lasing mode. The origin of this link, which comes directly from the laser field quantization, will be discussed, together with a quantitative connection between linewidth narrowing and g(2)(0).

Materials and methods

This section describes the emitter fabrication and measurement setup used to study emission from low-mode-volume, high-β micropillars. Employing electron-beam lithography and plasma reactive ion etching, each free-standing micropillar is processed from the same planar high-Q microcavity consisting of a lower and an upper AlAs/GaAs distributed Bragg reflector (DBR) with 25 and 30 layer pairs, respectively, and a single layer of InGaAs QDs as the active medium (Figure 1). The structures were planarized by the polymer benzocyclobutene (BCB) for mechanical stability and to suppress oxidation of the AlAs layers in the DBRs. Owing to a slight radial asymmetry in heterostructure layer thicknesses, different locations on the epitaxial wafer produce micropillars with different detuning between the fundamental cavity mode and QD resonance, thus allowing for control of modal gain. In addition, by varying micropillar diameters, we can influence the Purcell enhancement of spontaneous emission and thus the β-factor via its dependence on the modal volume and cavity Q-factor. In this way, we are able to fabricate emitters showing only luminescence (LED behavior), cavity-enhanced spontaneous emission, and high-β lasing. Details of the micropillar layout and processing have been previously reported37.

(left) Artist’s impression of an optically pumped QD micropillar consisting of two GaAs/AlAs distributed Bragg reflectors (DBRs) and QDs on a wetting layer. (right) SEM image of an 8 μm diameter micropillar, where part of the planarizing BCB layer (visible in the background) was mechanically removed to show the layers comprising the micropillar’s DBRs. SEM, scanning electron microscopy.

Figure 2 is a schematic representation of the spectroscopic measurement setup. Experiments are performed at 10 K by mounting the micropillar sample on a cold-finger of a liquid-helium flow cryostat. Continuous wave (cw) excitation is provided by an external-cavity laser tuned to 840 nm, which resonates with the wetting layer of QDs in the active region. μPL emission spectra are measured using either a grating spectrometer with a spectral resolution of 25 μeV or a scanning Fabry–Pérot interferometer with a free spectral range of 30 μeV and a spectral resolution of 0.5 μeV. The second-order photon autocorrelation function is measured using a fiber-coupled Hanbury Brown and Twiss (HBT) configuration equipped with Si-avalanche photodiode-based single-photon counting modules (SPCMs) with temporal resolutions of 260 ps.

Experimental setup. At the top left corner is a cryostat containing a sample that is pumped by a titanium:sapphire laser. The steady-state, continuous wave (cw) pumped photoluminescence is analyzed using a grating spectrometer connected to a CCD, a scanning Fabry-Pérot interferometer, a HBT setup with SPCMs and a TCSPC module. The cold mirror superimposes the pump laser onto the detection path, the pinhole provides spatial filtering, and the 850 nm longpass filter blocks scattered pump laser light. CCD, charge-coupled device; TCSPC, time-correlated single-photon counting.

A cQED model is used to compute the intracavity photon number, emission linewidth and second-order intensity correlation function for different pump powers and QD-micropillar configurations. The model is derived in the Heisenberg picture using a cluster expansion method to obtain a closed set of equations of motion for the polarization p, photon population np and electron (hole) carrier population ne(nh)36, 38, 39.

where the subscript σ=e (h) labels the electron (hole). Input parameters are the dephasing rate γ, the cavity photon decay rate 2γc, the spontaneous emission rate into non-lasing modes γnl and the nonradiative carrier-loss rate γnr. The light–matter coupling coefficient is

where  is the bulk material dipole matrix element,v is the laser field frequency, V is the optical mode volume,

is the bulk material dipole matrix element,v is the laser field frequency, V is the optical mode volume,  is the background permittivity, W is the amplitude of the passive optical mode eigenfunction at RQD, which is the location of the QDs within the optical cavity and the summation involves the overlap of the electron and hole envelop functions C(Rn) and V(Rn) over all unit cells within the active region. The last term in Equation (3) contains the laser pump power P, photon energy

is the background permittivity, W is the amplitude of the passive optical mode eigenfunction at RQD, which is the location of the QDs within the optical cavity and the summation involves the overlap of the electron and hole envelop functions C(Rn) and V(Rn) over all unit cells within the active region. The last term in Equation (3) contains the laser pump power P, photon energy  and carrier injection efficiency η, which accounts for the fraction of photoexcited carriers that actually end up populating the QD levels. Finally, NQD is the number of QDs within an inhomogeneously broadened active medium that are resonant with the microcavity field.

and carrier injection efficiency η, which accounts for the fraction of photoexcited carriers that actually end up populating the QD levels. Finally, NQD is the number of QDs within an inhomogeneously broadened active medium that are resonant with the microcavity field.

Initial modeling was performed using a nonequilibrium model, in which the gain region is assumed to consist of an inhomogeneous distribution of QDs, a quantum-well wetting layer and injection pumped bulk regions36. The model enables the description of spectral hole burning, plasma heating and population bottleneck, in terms of carrier–carrier and carrier–phonon scattering. These simulations led us to believe that this approach is overly complicated for the present problem because at a sufficiently low temperature the QD states are less coupled to the quantum well and, to a good approximation, the QDs interacting with the radiation field may be treated alone. Therefore, the present model tracks only those QD states and approximates all carrier transport effects via an injection efficiency, which is determined by fitting to experiment. This approach is closer to the earlier rate-equation treatments18, 40, except that we extended the derivation to include the linewidth and intensity correlation.

For the emission linewidth and equal-time second-order intensity correlation function, we use  and

and  , respectively, where

, respectively, where  , and the correlations

, and the correlations  and

and  , involving photon annihilation and creation operators b and b†, are evaluated under a stationary condition by solving the next level of equations of motion in the cluster expansions for

, involving photon annihilation and creation operators b and b†, are evaluated under a stationary condition by solving the next level of equations of motion in the cluster expansions for  and

and  :

:

Where v† creates an electron in the lower QD state and c annihilates an electron in the upper QD state. For the equal-time second-order correlation  , we solve

, we solve

Furthermore, for some emitters, the electron-hole polarization receives contributions from carrier correlations such as  , which give rise to coherence phenomena such as subradiance and superradiance. These correlations modify the input–output and

, which give rise to coherence phenomena such as subradiance and superradiance. These correlations modify the input–output and  behaviors of an emitter, as will be discussed in the next section41, 42, 43, 44.

behaviors of an emitter, as will be discussed in the next section41, 42, 43, 44.

Finally, the β-factor is computed from the rates of emission into the laser mode and into non-lasing modes according to the system parameters

where we use the steady-state solution of  .

.

Results and discussion

In this section, we present the results of measuring and modeling the five micropillars A–E. Table 1 lists the device parameters relevant to emission properties. The Q-factors in column 3 are obtained directly from experiment via dividing the measured emission energy by the spectral linewidth at the low-excitation plateau region (Figure 4). These Q-values are used in the modeling where they enter into equations (1) and (2) as  , the cavity photon lifetime due to outcoupling and background absorption. The β-factor and number of QDs resonant with the lasing-mode resonance NQD are extracted by simultaneously fitting the theoretical and experimental curves for intensity and linewidth versus pump power. We note that given the areal density of QDs (2 × 109 cm−2), the micropillar diameter determines the absolute number of QDs in the active layer. The effective number of QDs NQD also depends on the spectral overlap between the resonator mode and the inhomogeneously broadened QD emission band, which explains, for example, why NQD is higher for emitter A than for emitter B, which has a larger diameter. Two of the devices (micropillars A and B, with 1.7 and 2.0 μm diameters, respectively) operate purely as LEDs; one exhibits behaviors of a cavity-enhanced LED (micropillar C, with 2.0 μm diameter); the remaining two are lasers (micropillars D and E, with 2.5 μm diameters), with micropillar E exhibiting subradiance and then superradiance emission during the transition from spontaneous emission to lasing. The assignments are based on the combination of emission properties shown in Figures 2, 3 and 5, which we will discuss in the remainder of this section.

, the cavity photon lifetime due to outcoupling and background absorption. The β-factor and number of QDs resonant with the lasing-mode resonance NQD are extracted by simultaneously fitting the theoretical and experimental curves for intensity and linewidth versus pump power. We note that given the areal density of QDs (2 × 109 cm−2), the micropillar diameter determines the absolute number of QDs in the active layer. The effective number of QDs NQD also depends on the spectral overlap between the resonator mode and the inhomogeneously broadened QD emission band, which explains, for example, why NQD is higher for emitter A than for emitter B, which has a larger diameter. Two of the devices (micropillars A and B, with 1.7 and 2.0 μm diameters, respectively) operate purely as LEDs; one exhibits behaviors of a cavity-enhanced LED (micropillar C, with 2.0 μm diameter); the remaining two are lasers (micropillars D and E, with 2.5 μm diameters), with micropillar E exhibiting subradiance and then superradiance emission during the transition from spontaneous emission to lasing. The assignments are based on the combination of emission properties shown in Figures 2, 3 and 5, which we will discuss in the remainder of this section.

Input–output characteristics of QD-micropillar emitters for (a) LEDs, (b) cavity-enhanced LED and (c) lasers. The data points are from experiment and the gray curves are from theory. The left ordinate is the average detector counts over the integration period, and the right ordinate is the calculated average intracavity photon number np in the lasing mode. The dashed lines indicate the nominal lasing determined by np=1. The red numbers and lines indicate power law exponents and curves, respectively, as described in the main paper.

First, we look at the steady-state input–output relationship, which is an expedient and therefore frequently employed method to demonstrate lasing in conventional (β<<1) lasers. In Figure 3, the data points are from experiments, and the gray curves are computed using the cQED model. The matching of experimental and theoretical curves enables the extraction of the spontaneous emission rate into non-lasing modes γnl, the effective QD number NQD and the carrier injection efficiency η for each micropillar. The comparison also provides a calibration for the detector setup, enabling the conversion of detector counts over the integration period to intracavity photon numbers in the lasing mode (left and right ordinates in the top row of Figure 3). Using the conversion, the average intracavity photon number np reaches an excess of unity for emitters C, D and E, whereas np maximizes below unity for the non-lasing emitters A and B at saturation.

For low excitation, all five emitters have highly similar, slightly super-linear pump–power dependences, which we quantify by fitting to  , where I and P are intensity and pump power, respectively. The power law exponent r for separate portions of each input–output curve is given in Figure 3. At higher excitations, the input–output dependence separates into strong saturation for the LEDs A and B and nonlinear increase for the lasers D and E, and emitter C, the cavity-enhanced LED. The nonlinear increase, which signals the onset of stimulated emission, is considerably less pronounced than for conventional low-β lasers. As a result, it is necessary to look for further lasing confirmation in high-β situations.

, where I and P are intensity and pump power, respectively. The power law exponent r for separate portions of each input–output curve is given in Figure 3. At higher excitations, the input–output dependence separates into strong saturation for the LEDs A and B and nonlinear increase for the lasers D and E, and emitter C, the cavity-enhanced LED. The nonlinear increase, which signals the onset of stimulated emission, is considerably less pronounced than for conventional low-β lasers. As a result, it is necessary to look for further lasing confirmation in high-β situations.

Currently, further confirmation of lasing often comes from the presence of a noticeable decrease in emission linewidth with increasing excitation. With conventional cavities where β<<1, the onset of linewidth narrowing occurs abruptly at the lasing threshold and typically scales inversely proportional with the excitation strength, consistent with the Schawlow-Townes description33. Alternatively, it is reported that with large β, the narrowing is less pronounced and then becomes indiscernible in the limiting case of β=120, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25.

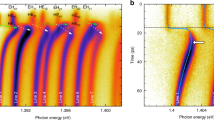

Figure 4 shows plots of the emission linewidth versus pump power for the five emitters. The data points are measured results obtained from a scanning Fabry-Pérot interferometer or from the decay time of g(2)(τ). First, the low pump–power plateaus show that emitters B, C, D and E have similar passive cavity linewidths of approximately 40–70 μeV, whereas emitter A has a larger passive cavity linewidth of approximately 140 μeV, indicating larger optical losses in this smallest diameter micropillar. With increasing pump power, emitters A and B show only slight decreases in linewidth, which support their assignments as LEDs. The linewidth reduction is partially from an increase in the amplified spontaneous emission, which the model describes (gray curves in Figure 4a), and partly from saturation of absorption losses, which the model does not take into account. Figures 4b and 4c indicate appreciably greater linewidth narrowing for emitters C, D and E. The reduction of over two orders is due mostly to the onset of stimulated emission, which is reproduced relatively well by the model. A discrepancy between theory and experiment arises at high excitation, with the theoretical curves indicating significantly narrower linewidths than those observed experimentally. The measured linewidths are not spectrometer resolution limited, but they may contain contributions from spectral fluctuations and temperature-induced jitter at a timescale smaller than the sweep time (50 ms per free spectral range) of the scanning Fabry–Pérot interferometer. Interestingly, the calculated minimum linewidth of approximately 0.1 μeV, which translates to a coherence time of 13ns, matches well with the coherence time of ≈20 ns reported for a similar QD-micropillar laser45.

Spectral linewidth versus pump power of QD-micropillar emitters for (a) LEDs, (b) cavity-enhanced LED and (c) lasers. The gray curves are from theory, and the data points are from experiment. Filled symbols indicate the scanning Fabry–Pérot interferometer or spectrometer results, and open symbols indicate the results from the analysis of  measurements.

measurements.

Other than the discrepancy possibly caused by the scanning Fabry-Pérot interferometer measurement sweep time, the cQED model generally agrees with the experiment. The data points and curves in Figure 3 show noticeable but acceptable differences. Varying γnl, NQD and η to obtain better linewidth agreement would degrade the good agreement of the input–output curves. We choose not to adjust the dephasing associated with  , which will change the linewidth independently of input–output behavior, but rather to base all effective scattering rates on reported results from experiments or quantum-kinetic calculations39, 46, 47. For the same reason, the polarization dephasing γ is not treated as a free parameter in our curve fitting. Furthermore, the model neglects that for high-Q cavities there may be excitation-dependent bleaching of absorption, which will result in a narrower linewidth48.

, which will change the linewidth independently of input–output behavior, but rather to base all effective scattering rates on reported results from experiments or quantum-kinetic calculations39, 46, 47. For the same reason, the polarization dephasing γ is not treated as a free parameter in our curve fitting. Furthermore, the model neglects that for high-Q cavities there may be excitation-dependent bleaching of absorption, which will result in a narrower linewidth48.

The remaining task to perform is distinguishing between lasing and amplified spontaneous emission; both phenomena exhibit highly similar excitation dependences on emission intensity and linewidth (compare Figures 3b and 4b with Figures 3c and 4c). A concern is that the plots in Figure 3b and 4b may easily be mistaken as evidence for lasing in an ideal β=1 device because they show appreciable linewidth narrowing and a basically straight log–log input–output curve. To definitively separate laser and cavity-enhanced LED operation, it is necessary to examine the equal-time intensity correlation g(2)(0). In recent years, there has been a considerable effort to improve techniques and equipment for determining g(2)(0) because of the importance of characterizing single-photon and entangled-photon sources and, to a lesser extent, of verifying lasing, particularly in the high-β regime8, 38, 49. Performing the necessary HBT measurement remains labor and equipment demanding, as one faces the experimental issue of time resolution in the case of thermal light38, 49. The challenge is that the coherence time of emission, which determines the timescales of g(2)(τ), is usually much shorter than the timing resolution of the single-photon counting based HBT setups. This issue can be circumvented by using a streak-camera with a dual time-base49; however, the cost is a significantly lower quantum efficiency, which again imposes constraints on measuring g(2) (τ) in the thermal regime at low emission rates.

For chaotic light, the Siegert relation links the normalized first-order correlation function  to the second-order photon autocorrelation function

to the second-order photon autocorrelation function  with c=1. A common approach is to model the intermediate regime between coherent and chaotic light with this function as well, where 0<c<1. Homogenously broadened emission lines, as in our case, have a Lorentzian shape in the frequency spectrum; therefore, the envelope of the normalized first-order correlation function

with c=1. A common approach is to model the intermediate regime between coherent and chaotic light with this function as well, where 0<c<1. Homogenously broadened emission lines, as in our case, have a Lorentzian shape in the frequency spectrum; therefore, the envelope of the normalized first-order correlation function  is an exponential function decaying with the coherence time as a constant. As the area under the

is an exponential function decaying with the coherence time as a constant. As the area under the  function is conserved under convolution with the instrument impulse response function, it is now possible to estimate c when the area and an estimate of the coherence time are given. Thus, by integrating over the measured raw

function is conserved under convolution with the instrument impulse response function, it is now possible to estimate c when the area and an estimate of the coherence time are given. Thus, by integrating over the measured raw  function, we estimate the original equal-time second-order photon auto-correlation function as

function, we estimate the original equal-time second-order photon auto-correlation function as  for a Lorentzian spectrum with linewidth ΔE (full-width at half-maximum). The data points shown in Figure 5 demonstrate the measured g(2)(0) versus pump power for all the devices. The data indicating thermal emission are obtained by analyzing the area under the

for a Lorentzian spectrum with linewidth ΔE (full-width at half-maximum). The data points shown in Figure 5 demonstrate the measured g(2)(0) versus pump power for all the devices. The data indicating thermal emission are obtained by analyzing the area under the  function, whereas the data showing the onset of stimulated emission or lasing are obtained directly by fitting the convolved model function to the HBT measurements. For emitter C, like LEDs A and B, g(2)(0) stays at ~2 through the excitation range. Alternatively, micropillars D and E clearly exhibit a transition from thermal light (g(2)(0)≈2) to coherent light (g(2)(0)≈1). In all cases, there is appreciable scattering in the data describing the operation with thermal emission because of the time resolution and low emission rate challenges discussed in the previous paragraph. The gray curves are from the model, using the same input parameters as in Figures 2 and 3.

function, whereas the data showing the onset of stimulated emission or lasing are obtained directly by fitting the convolved model function to the HBT measurements. For emitter C, like LEDs A and B, g(2)(0) stays at ~2 through the excitation range. Alternatively, micropillars D and E clearly exhibit a transition from thermal light (g(2)(0)≈2) to coherent light (g(2)(0)≈1). In all cases, there is appreciable scattering in the data describing the operation with thermal emission because of the time resolution and low emission rate challenges discussed in the previous paragraph. The gray curves are from the model, using the same input parameters as in Figures 2 and 3.

Equal-time intensity correlation versus pump power for QD-micropillar (a) LEDs, (b) cavity-enhanced LED and (c) lasers. The gray curves are from theory. The data points are from experiment, where the solid symbols indicate  analysis by integration and the open symbols indicate fits considering the instrument impulse response of the TCSPC setup. TCSPC, time-correlated single-photon counting.

analysis by integration and the open symbols indicate fits considering the instrument impulse response of the TCSPC setup. TCSPC, time-correlated single-photon counting.

Figure 5b depicts a peculiar behavior, where g(2)(0) for emitter C first reduces with increasing excitation, then reverses at approximately 100 μW pump power and eventually returns to g(2)(0)=2 for pump power >1 mW. Hence, despite the indications from Figures 3b and 4b, emitter C does not represent a high-β laser, but it is a good example of the importance of g(2)(0) measurements. We suspect the g(2)(0) behavior is due to the carrier-density dependence of the dephasing rate, which has been reported to be strong in QD structures50, 51. The difference between emitter C and the lasers D and E may be that with a smaller diameter it operates with a higher carrier density to achieve gain. The present model neglects the carrier-density dependence of the dephasing coefficient, which explains the discrepancy between the calculated and measured results in Figure 4b.

In addition, micropillar E clearly demonstrates g(2)(0)>2 before decreasing to unity with increasing excitation. The observed super-thermal bunching is one manifestation of superradiance41, 43; the occurrence in semiconductor micro- or nanocavities is presently being intensely investigated44, 52, 53, 54, 55. Based on modeling the experimental result, the higher photon bunching results from correlations among QDs. The appearance of this correlation sensitively depends on the QD number, which explains the different g(2)(0) power dependences of emitters D and E, which otherwise have very similar emission characteristics.

The correlation also affects the input–output curve for emitter E in Figure 3c by contributing to the intensity jump43. Fitting the experimental curve with a model including inter-QD correlation gives β=0.72. Neglecting the inter-QD correlations gives a much lower estimation of β=0.23, which is incorrect because of the unmistakable g(2)(0)>2 exhibited by emitter E, as shown in Figure 5c.

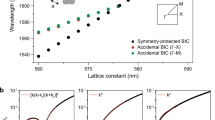

The measured and calculated information from the five QD-micropillars provide a relatively complete picture of the broad range of emission properties exhibited by high-β devices. To understand the underlying physics governing the widely different behaviors, it is necessary to condense the information from Figures 3, 4, 5. The first hint comes from noticing that the emission linewidth narrowing exhibited by all emitters appears very similar when the linewidth narrowing is plotted as a function of intracavity photon number np, rather than the pump power. In Figure 6, the curves calculated for 8500<Q<32000 are essentially identical in terms of the onset and slope of the line narrowing when one factors out the different low excitation plateaus due to the differences in passive cavity linewidth. The experimental data follows the same trend. Despite the large number of experimental data points, the scatter is minimal.

Extending upon Figure 6, we plot g(2)(0) versus the intracavity photon number (Figure 7). The blue curves are calculated using the broad range of input parameters listed in Table 1 for emitters A–D ( ). The essentially overlapping curves strongly indicate a single functional device-independent relationship regarding lasing. Within the standard deviation of the measurement, the experimental results support this claim. For clarity, the experimental data from the four micropillars are combined and presented in terms of an average and standard deviation at an averaged intracavity photon number. There is noticeably more scatter in Figure 6 because of the challenges in measuring g(2)(0) for low-intensity thermal emission, where the accuracy is limited by the combination of the low signal-to-noise ratio and short coherence time. Nevertheless, both theory and experiment appear to indicate a lasing threshold when the intracavity photon number reaches approximately 102, independent of emitter configuration. The red curve and data points are for emitter E, which exhibits super-thermal bunching, indicating the presence of sub- and super-radiance with changing pump power42, 43–44, 52, 53, 54, 55. Again, there is an interdependence between photon correlations and photon number, in addition to the suggestion of a lower intracavity photon number necessary to reach the lasing threshold when superradiance is present43.

). The essentially overlapping curves strongly indicate a single functional device-independent relationship regarding lasing. Within the standard deviation of the measurement, the experimental results support this claim. For clarity, the experimental data from the four micropillars are combined and presented in terms of an average and standard deviation at an averaged intracavity photon number. There is noticeably more scatter in Figure 6 because of the challenges in measuring g(2)(0) for low-intensity thermal emission, where the accuracy is limited by the combination of the low signal-to-noise ratio and short coherence time. Nevertheless, both theory and experiment appear to indicate a lasing threshold when the intracavity photon number reaches approximately 102, independent of emitter configuration. The red curve and data points are for emitter E, which exhibits super-thermal bunching, indicating the presence of sub- and super-radiance with changing pump power42, 43–44, 52, 53, 54, 55. Again, there is an interdependence between photon correlations and photon number, in addition to the suggestion of a lower intracavity photon number necessary to reach the lasing threshold when superradiance is present43.

Equal-time intensity correlation versus intracavity photon number in lasing mode for all micropillar emitters. The data are separated for emitter F, which exhibits radiative emitter coupling, and emitters A–D, which do not. The inset shows data points from all emitters plotted separately. In the main figure, data from emitters A–D are separated into bins of different average linewidths. The average and standard deviation are plotted in each bin. The calculated curves from all emitters are plotted. All curves except one (dashed curve from emitter C), are indistinguishable from one another. We suspect the separation of the dashed and solid curves to be due to numerical error.

As linewidth narrowing will likely continue to be used as proof of lasing, it may be helpful to arrive at some quantitative indication of how much narrowing is necessary to support a lasing claim. Figure 8 shows the result of combining Figures 6 and 7. The abscissa is the emission linewidth divided by the passive cavity width. To more clearly demonstrate the trend in the experimental data, we again combined the results from the emitters and plot only the averages and the standard deviations. According to theory (gray curves), a greater than 102 reduction is necessary. This refers to the fundamental linewidth determined solely by spontaneous emission. The measured data demonstrate a less stringent requirement of a reduction to approximately 16% of the passive cavity width, which is observed in emitter E. The apparent discrepancy arises because the measured linewidths of the lasing emitters are further broadened by frequency jitter.

Equal-time intensity correlation versus linewidth reduction for all emitters. The linewidth reduction is defined as the emission linewidth divided by the passive cavity width. The measured data for all emitters are combined. The averages and standard deviations at given linewidth intervals are plotted as blue diamonds and error bars, respectively. The calculated curves for emitters A, B and D all lay on the solid curve. Emitter C is shown by the dashed curve.

Conclusions

This paper describes research motivated by considerable discussions involving near-unity spontaneous-emission factor ( ) emitters, in particular their unique emission properties during the transition from spontaneous emission to lasing. There are two aspects to our investigation. First is to learn as much as possible about the emission properties of high-β emitters. For the task, we fabricate, measure and model a wide variety of experimental configurations, ranging from LEDs to lasers. In addition to the usual characterizations involving the excitation dependences on emission intensity and linewidth, we measure and calculate the second-order intensity correlation g(2)(τ) as a function of pump power. The importance of examining all three properties is illustrated very well by an emitter whose properties fall between those of an LED and a laser: a cavity-enhanced LED. Importantly, it can easily be mistaken for a laser because the intensity and linewidth excitation dependences are similar to those of lasers. However, the g(2)(0) clearly indicates thermal statistics. The importance of g(2)(0) is further reinforced by the results for a laser that exhibits superradiant emitter coupling as it approaches the lasing threshold. Obviously, without knowing g(2)(0), the interesting property would have been missed, and equally important, an underestimation of the spontaneous emission factor would have resulted.

) emitters, in particular their unique emission properties during the transition from spontaneous emission to lasing. There are two aspects to our investigation. First is to learn as much as possible about the emission properties of high-β emitters. For the task, we fabricate, measure and model a wide variety of experimental configurations, ranging from LEDs to lasers. In addition to the usual characterizations involving the excitation dependences on emission intensity and linewidth, we measure and calculate the second-order intensity correlation g(2)(τ) as a function of pump power. The importance of examining all three properties is illustrated very well by an emitter whose properties fall between those of an LED and a laser: a cavity-enhanced LED. Importantly, it can easily be mistaken for a laser because the intensity and linewidth excitation dependences are similar to those of lasers. However, the g(2)(0) clearly indicates thermal statistics. The importance of g(2)(0) is further reinforced by the results for a laser that exhibits superradiant emitter coupling as it approaches the lasing threshold. Obviously, without knowing g(2)(0), the interesting property would have been missed, and equally important, an underestimation of the spontaneous emission factor would have resulted.

The second aspect of our research involves consolidating the vast amount of data to identify and understand the physics underlying the broad range of behaviors. Progress is made with the discovery that the experimental and theoretical results for all the emitters seemingly fit into two relationships: linewidth reduction versus intracavity photon number and g(2)(0) versus intracavity photon number. Hence, laser (or non-laser) action comes from achieving a given photon number above unity, and device parameters, such as Q and β factors, QD density, dipole matrix element, carrier transport and optical mode volume, determine the lasing threshold by affecting the intracavity photon number.

References

Blood P . The laser diode: 50 years on. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron 2013; 19: 1503201.

Vahala KJ . Optical microcavities. Nature 2003; 424: 839–846.

Lodahl P, van Driel AF, Nikolaev IS, Irman A, Overgaag K et al. Controlling the dynamics of spontaneous emission from quantum dots by photonic crystals. Nature 2004; 430: 654–657.

De Giorgio V, Scully MO . Analogy between the laser threshold region and a second-order phase transition. Phys Rev A 1970; 2: 1170–1177.

Rice PR, Carmichael HJ . Photon statistics of a cavity-QED laser: a comment on the laser–phase transition analogy. Phys Rev A 1994; 50: 4318–4329.

Gourley PL . Microstructured semiconductor lasers for high-speed information processing. Nature 1994; 371: 571–577.

Noda S . Seeking the ultimate nanolaser. Science 2006; 314: 260–261.

Stefan TJ, Noelia VT, Gordon C, Stefan K, Ian MR et al. Thresholdless Lasing of Nitride Nanobeam Cavities 2016; arXiv: 1603.06447.

Salehzadeh O, Djavid M, Tran NH, Shih I, Mi ZT . Optically pumped two-dimensional MoS2 lasers operating at room-temperature. Nano Lett 2015; 15: 5302–5306.

Bergman DJ, Stockman MI . Surface plasmon amplification by stimulated emission of radiation: quantum generation of coherent surface plasmons in nanosystems. Phys Rev Lett 2003; 90: 027402.

Lu YJ, Wang CY, Kim J, Chen HY, Lu MY et al. All-color plasmonic nanolasers with ultralow thresholds: autotuning mechanism for single-mode lasing. Nano Lett 2014; 14: 4381–4388.

Purcell EM . Spontaneous emission probabilities at radio frequencies. Phys Rev 1946; 69: 681.

Lodahl P, Mahmoodian S, Stobbe S . Interfacing single photons and single quantum dots with photonic nanostructures. Rev Mod Phys 2015; 87: 347–400.

Chow WW, Crawford MH . Analysis of lasers as a solution to efficiency droop in solid-state lighting. Appl Phys Lett 2015; 107: 141107.

Reithmaier JP, Sęk G, Löffler A, Hofmann C, Kuhn S et al. Strong coupling in a single quantum dot-semiconductor microcavity system. Nature 2004; 432: 197–200.

Manga Rao VSC, Hughes S . Single quantum-dot Purcell factor and β factor in a photonic crystal waveguide. Phys Rev B 2007; 75: 205437.

De Martini F, Innocenti G, Jacobovitz GR, Mataloni P . Anomalous spontaneous emission time in a microscopic optical cavity. Phys Rev Lett 1987; 59: 2955–2958.

Björk G, Yamamoto Y . Analysis of semiconductor microcavity lasers using rate equations. IEEE J Quantum Electron 1991; 27: 2386–2396.

Jin R, Boggavarapu D, Sargent M, Meystre P, Gibbs HM et al. Photon-number correlations near the threshold of microcavity lasers in the weak-coupling regime. Phys Rev A 1994; 49: 4038–4042.

Björk G, Karlsson A, Yamamoto Y . Definition of a laser threshold. Phys Rev A 1994; 50: 1675–1680.

Ning CZ . What is laser threshold? IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron 2013; 19: 1503604.

Coldren LA . What is a diode laser oscillator? IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron 2013; 19: 1503503.

Yokoyama H . Physics and device applications of optical microcavities. Science 1992; 256: 66–70.

DeMartini F, Jacobovitz GR . Anomalous spontaneous-stimulated-decay phase transition and zero-threshold laser action in a microscopic cavity. Phys Rev Lett 1988; 60: 1711–1714.

Khajavikhan M, Simic A, Katz M, Lee JH, Slutsky B et al. Thresholdless nanoscale coaxial lasers. Nature 2012; 482: 204–207.

Takiguchi M, Taniyama H, Sumikura H, Birowosuto MD, Kuramochi E et al. Systematic study of thresholdless oscillation in high-β buried multiple-quantum-well photonic crystal nanocavity lasers. Opt Express 2016; 24: 3441–3450.

Ye Y, Wong ZJ, Lu XF, Ni XJ, Zhu HY et al. Monolayer excitonic laser. Nat Photonics 2015; 9: 733–737.

Jang H, Karnadi I, Pramudita P, Song JH, Kim KS et al. Sub-microWatt threshold nanoisland lasers. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 8276.

Wu SF, Buckley S, Schaibley JR, Feng LF, Yan JQ et al. Monolayer semiconductor nanocavity lasers with ultralow thresholds. Nature 2015; 520: 69–72.

Prieto I, Llorens JM, Muñoz-Camúñez LE, Taboada AG, Canet-Ferrer J et al. Near thresholdless laser operation at room temperature. Optica 2015; 2: 66–69.

Armstrong JA, Smith AW . Intensity fluctuations in a GaAs laser. Phys Rev Lett 1965; 14: 68–70.

Mohideen U, Slusher RE, Jahnke F, Koch SW . Semiconductor microlaser linewidths. Phys Rev Lett 1994; 73: 1785–1788.

Schawlow AL, Townes CH . Infrared and optical masers. Phys Rev 1958; 112: 1940–1949.

Choi YS, Rakher MT, Hennessy K, Strauf S, Badolato A et al. Evolution of the onset of coherence in a family of photonic crystal nanolasers. Appl Phys Lett 2007; 91: 031108.

Elvira D, Hachair X, Verma VB, Braive R, Beaudoin G et al. Higher-order photon correlations in pulsed photonic crystal nanolasers. Phys Rev A 2011; 84: 061802.

Chow WW, Jahnke F, Gies C . Emission properties of nanolasers during the transition to lasing. Light Sci Appl 2014; 3: e201.

Lermer M, Gregersen N, Dunzer F, Reitzenstein S, Höfling S et al. Bloch-wave engineering of quantum dot micropillars for cavity quantum electrodynamics experiments. Phys Rev Lett 2012; 108: 057402.

Ulrich SM, Gies C, Ates S, Wiersig J, Reitzenstein S et al. Photon statistics of semiconductor microcavity lasers. Phys Rev Lett 2007; 98: 043906.

Chow WW, Jahnke F . On the physics of semiconductor quantum dots for applications in lasers and quantum optics. Prog Quantum Electron 2013; 37: 109–184.

Yokoyama H, Brorson SD . Rate equation analysis of microcavity lasers. J Appl Phys 1989; 66: 4801–4805.

Dicke RH . Coherence in spontaneous radiation processes. Phys Rev 1954; 93: 99–110.

Svidzinsky AA, Yuan LQ, Scully MO . Quantum amplification by superradiant emission of radiation. Phys Rev X 2013; 3: 041001.

Leymann HAM, Foerster A, Jahnke F, Wiersig J, Gies C . Sub- and superradiance in nanolasers. Phys Rev Appl 2015; 4: 044018.

Temnov VV, Woggon U . Superradiance and subradiance in an inhomogeneously broadened ensemble of two-level systems coupled to a low-Qcavity. Phys Rev Lett 2005; 95: 243602.

Tempel JS, Akimov IA, Aßmann M, Schneider C, Höfling S et al. Extrapolation of the intensity autocorrelation function of a quantum-dot micropillar laser into the thermal emission regime. J Opt Soc Am B 2011; 28: 1404–1408.

Gomis-Bresco J, Dommers S, Temnov VV, Woggon U, Laemmlin M et al. Impact of Coulomb scattering on the ultrafast gain recovery in InGaAs quantum dots. Phys Rev Lett 2008; 101: 256803.

Kurtze H, Seebeck J, Gartner P, Yakovlev DR, Reuter D et al. Carrier relaxation dynamics in self-assembled semiconductor quantum dots. Phys Rev B 2009; 80: 235319.

Strauf S, Hennessy K, Rakher MT, Choi YS, Badolato A et al. Self-tuned quantum dot gain in photonic crystal lasers. Phys Rev Lett 2006; 96: 127404.

Wiersig J, Gies C, Jahnke F, Aβmann M, Berstermann T et al. Direct observation of correlations between individual photon emission events of a microcavity laser. Nature 2009; 460: 245–249.

Lorke M, Chow WW, Nielsen TR, Seebeck J, Gartner P et al. Anomaly in the excitation dependence of the optical gain of semiconductor quantum dots. Phys Rev B 2006; 74: 035334.

Laucht A, Hauke N, Villas-Bôas JM, Hofbauer F, Böhm G et al. Dephasing of exciton polaritons in photoexcited InGaAs quantum dots in GaAs nanocavities. Phys Rev Lett 2009; 103: 087405.

Jahnke F, Gies C, Aβmann M, Bayer M, Leymann HAM et al. Giant photon bunching, superradiant pulse emission and excitation trapping in quantum-dot nanolasers. Nat Commun 2016; 7: 11540.

ll GTN, Kim JH, Lee J, Wang YR, Wójcik AK et al. Giant superfluorescent bursts from a semiconductor magneto-plasma. Nat Phys 2012; 8: 219–224.

Scheibner M, Schmidt T, Worschech L, Forchel A, Bacher G et al. Superradiance of quantum dots. Nat Phys 2007; 3: 106–110.

Mlynek JA, Abdumalikov AA, Eichler C, Wallraff A . Observation of Dicke superradiance for two artificial atoms in a cavity with high decay rate. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 5186.

Acknowledgements

The research is funded in part by the European Research Council under the Seventh Framework ERC Grant Agreement No. 615613 of the European Union, the German Research Foundation via the projects RE2974/5-1, Ka2318 7-1 and JA 619/10-3, and the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC04-94AL85000. WWC thanks the Technical University Berlin for hospitality and the German Research Foundation via collaborative research center 787 for travel support. CG and FJ gratefully acknowledge financial support from the German Science Foundation (DFG). FJ further acknowledges support from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kreinberg, S., Chow, W., Wolters, J. et al. Emission from quantum-dot high-β microcavities: transition from spontaneous emission to lasing and the effects of superradiant emitter coupling. Light Sci Appl 6, e17030 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2017.30

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2017.30

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Wafer-scale epitaxial modulation of quantum dot density

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Quantum-dot micropillar lasers subject to coherent time-delayed optical feedback from a short external cavity

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Determining random lasing action

Nature Reviews Physics (2019)

-

A quantum optical study of thresholdless lasing features in high-β nitride nanobeam cavities

Nature Communications (2018)

-

Quantum-optical spectroscopy of a two-level system using an electrically driven micropillar laser as a resonant excitation source

Light: Science & Applications (2018)