Abstract

Unlike inorganic quantum dots, fluorescent graphene quantum dots (GQDs) display excitation-dependent multiple color emission. In this study, we report N-doped GQDs (N-GQDs) with tailored single color emission by tuning π-conjugation degree, which is comparable to the inorganic quantum dot. Starting from citric acid and diethylenetriamine, as prepared N-GQDs display blue, green, and yellow light emission by changing the reaction solvent from water, dimethylformamide (DMF), and solvent free. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, ultraviolet-visible spectra results clearly show the N-GQDs with blue emission (N-GQDs-B) have relatively short effective conjugation length and more carboxyl group because H2O is a polar protic solvent, which tends to donate proton to the reagent to depress the H2O elimination reaction. On the other hand, the polar aprotic solvent (DMF) cannot donate hydrogen, the elimination of H2O is promoted and more nitrogen units enter GQD framework. With the increase of effective π-conjugation length and N content, the emission band of N-GQDS red-shifts to green and yellow. We also demonstrate that N-GQDs could be a potential great biomarker for fluorescent bioimaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fluorescent graphene quantum dots (GQDs) and carbon nanodots (CNDs) with tunable emissions are considered to be the next-generation nanomaterials due to the superiority in resistance to photobleaching, low toxicity, excellent biocompatibility, low cost, and abundance of raw materials in nature1,2,3. They have been demonstrated potential applications on optical detection probes4, bioimaging probes5,6, theranostic agent7,8, light-emitting diode materials9,10, and efficient visible light-active photocatalysts11,12,13, and so on. Recent advances in synthesis of CNDs allow them to be obtained from fine carbon structures like carbon fiber14, graphene15, and coal16 through top-down routes, which breaks the bulk carbon materials into small pieces via physical or chemical methods. But, low photoluminescent (PL) quantum yields (QY) limit their further practical applications. Compared with top-down routes, the bottom-up routes have obvious advantages in tuning the composition and photo properties by the careful selection of precursors and carbonization conditions. The bottom-up routes give relative high PL QY and yield17,18. However, because of the nature of GQDs, tailor-made control of their optical properties is extremely challenging and is one of the key technologies for putting these materials into practical applications.

Interestingly, most of the resulting GQDs exhibited blue or green emission, despite distinct techniques for the fabrication19. Broad excitation-dependent multiple color emission is a typical character. Although the exact PL mechanism is still under debate, it has been demonstrated the PL of GQDs origining from electron–hole recombination, quantum size effect, zigzag sites, and defect effect20,21,22. Eda et al. demonstrated that the blue emission was derived from isolated sp2 cluster within carbon–oxygen sp3 matrix, leading to radiative recombination of electron and hole23. Seo et al. have revealed that the green luminescence of GQDs originated from the defect states with oxygenous function groups, whereas the blue luminescence of GQDs was dominated by intrinsic state of sp2 structure24. Yang et al. provided further evidence from transient spectra. A charge separation could exist between sp2 cluster and defect states, leading to a defect state luminescence in a dominated role for green emission GQDs20,21,25,26. However, there is rare report on the synthesis of highly luminescent GQDs with tailoring color emissions like inorganic nanocrystals. The development of facile and practical processing method to obtain pure color emission GQDs still remains a challenging issue. In addition, it is worth to note that the practical bio-related applications of GQDs in bioimaging are still strongly bounded due to the following issues: The PL of most GQDs have been reported is induced by ultraviolet (UV) excitation, which tends to cause side effects and low penetration depth for the bio-system. Blue emission is close to the autofluorescence.

Herein, we synthesize N-doped GQDs (N-GQDs) with tailoring color (blue, green, and yellow) emissions by simply changing the reaction solvent in the hydrothermal reaction. Blue, green, and yellow emissions N-GQDs are obtained from water, dimethylformamide (DMF), and solvent free, respectively. It should be noted that the nature of solvent strongly affects the composition and properties of N-GQDs. The N-GQDs prepared from protic solvent only emit blue light, but the green light comes from N-GQDs synthesized in aprotic solvent system. It extends the emission of N-GQDs from single blue emission in our previous report to green and yellow emission in current one. The PL spectra confirm that the N-GQDs clearly show excitation-independent emission, and single exponential lifetime decay, indicating a single emission center for each sample. This property will be benefit for the fabrication of pure color light-emitting device. The PL excitation (PLE) spectra display that the excitation wavelengths shift from 350, 460, to 480 nm for N-GQDs-B, G, and Y (B, G, and Y stand for blue, green, and yellow), respectively. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) results show decreasing trend of the relative amount of O, and increasing trend of the amount of sp2 C, indicating the effective conjugation length of N-GQDs turns larger and larger from N-GQDs-B, G to Y. N 1s and O 1s XPS results exhibit that the increasing amount of the pyrrolic N and carbonyl (C=O) and the decreasing graphite N amount and quinone from N-GQDs-B to Y, implying the surface groups are related to pyrrole or pyrrolidone groups. We propose that larger effective conjugation length combined with nitrogenous functional group may contribute to the red-shift of PL emission. Furthermore, we demonstrate that these N-GQDs could be a good bioimaging agent for the bio-related applications.

Materials and methods

Materials

All chemicals used were of analytical pure grade and were used without any further purification. Citric acid monohydrate (CA), diethylenetriamine (DETA), and DMF were purchased from Aladdin Reagent Company or Beijing Chemical Reagent Company.

Synthesis of N-GQDs-B

Add 1 mmol CA (0.21 g), 3 mmol DETA (0.34 g), and 5 mL H2O into Teflon-lined stainless autoclave (10 mL), and keep stirring until form a clear solution. Then place the sealed autoclave vessles into an electric oven, which is set at 180 °C and hold for 6 h. The solution is washed by abundant ethanol and centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 15 min. The as-prepared N-GQDs-B can be collected and redispersed into water easily.

Synthesis of N-GQDs-G

Put 1 mmol CA (0.21 g), 3 mmol DETA (0.34 g), and 5 mL DMF into Teflon-lined stainless autoclave (10 mL), and keep stirring until form a clear solution. Then place the sealed autoclave in an electric oven which is set at 180 °C for 6 h. The precipitation is collected by adding reaction solution into huge amount of mixed solvent solution (at least 10 times petroleum ether/ethyl acetate of 1/4) and centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 15 min. The as-prepared N-GQDs-G can be collected and redispersed into water easily.

Synthesis of N-GQDs-Y

Place 1 mmol CA (0.21 g) and 3 mmol DETA (0.34 g) into Teflon-lined stainless autoclave (10 mL), and keep stirring for 30 min. Then place the sealed autoclave in an electric oven which is set at 180 °C for 6 h. The precipitation is collected by adding reaction solution into huge amount of mixed solvent solution (at least 10 times petroleum ether/ethyl acetate of 1/4) and centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 15 min. The as-prepared N-GQDs-Y can be collected and redispersed into water easily.

Characterization

The FEI-Tecnai G2 transmission electron microscope (TEM) operating at 200 kV was used to recorded high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images and fast Fourier transform (FFT) spot diagrams. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images were captured on the Multimode 8 (Bruker Co. CA. USA) in tapping mode. X-ray photoelectron spectra were obtained on a Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250 Multitechnique Surface Analysis with Al Ka X-ray monochromator, pass energy 20 eV. The Edinburgh FLS 920 spectrometer with a calibrated integrating sphere was used to measure absolute QY. Lifetime measurement of GQDs was carried out on the Edinburgh TSCPS FLS 920. UV-Vis (ultraviolet-visible) absorption spectra were performed by the Shimadzu UV-2450 spectrophotometer. Fourier transform-infrared spectra were obtained by the Bruker Vertex 70 spectrometer using KBr pellets. Fluorescence emission spectra were performed on the LS-55 fluorophotometer.

Results and discussion

CA is a unique molecule for the synthesis of high fluorescent N-GQDs17,18. Normally, only blue emission carbon nanoparticles were prepared from the hydrothermal route, even the size of N-GQDs increase from ∼2 nm to 7 nm18. In this report, CA is still chosen as carbon source and DETA as N source for synthesis of N-GQDs. When the reaction is carried out in the water solution, the as-obtained N-GQDs show the blue emission (named as N-GQDs-B) as previous reports27,28. Instead of the water with DMF, the N-GQDs exhibit strong green light emission under excitation wavelength of 460 nm (denoted as N-GQDs-G). In the synthesis of N-GQDs, the difference of reaction conditions is the solvent, which changes from H2O to DMF. N-GQDs-B is formed in polar protic solvent H2O. If the H2O is replaced with ethanol or ethylene glycol, blue emission N-GQDs are obtained. On the contrary, DMF is polar aprotic solvent in the reaction of N-GQDs emitted green light. Furthermore, N-GQDs-G is also synthesized if the reaction solvent is employed 1,4-dioxane or tetrahydrofuran (Supplementary Fig. S1). Furthermore, the N-GQDs can also be prepared with absence of solvent. The as-prepared N-GQDs exhibit yellow light emission under excitation wavelength of 480 nm (denoted as N-GQDs-Y). On the base of above results, the emission of N-GQDs strongly depends on the properties of solvent. The formation of GQD is a H2O elimination reaction between -OH and -H inter- and intra-molecules to form six member ring and conjugation double bond in the basic environment. As a polar protic solvent, water tends to donate proton to reagent. That depresses the elimination of H2O inter- and intra-molecules. That leads to a short effective conjugation length and more carboxyl groups left on the GQDs surface. DMF, as a polar aprotic solvent, cannot donate hydrogen in the reaction. Relative large effective conjugation length of GQDs is a result of dehydration reaction happened between CA and intra-molecules. Although DETA can donate the proton in the case of solvent free, it will bring more N elements into the GQDs, which results higher amount of N in GQDs. In addition, the exacerbated intra-molecules dehydration reaction will increase the conjugation degree of GQDs. We propose that emission red-shift originates from large effective π-conjugation length combine with high N content.

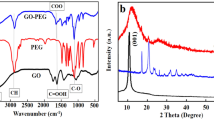

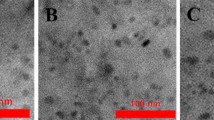

Figure 1 shows TEM, HRTEM, and AFM images of N-GQDs-B, G, and Y, respectively. The as-prepared N-GQDs show well dispersion in water solution. The particle size distribution of N-GQDs obeys a Gaussian distribution. The most probable sizes are 2.12 ± 0.31, 2.34 ± 0.25, and 2.58 ± 0.34 nm of N-GQDs-B, G, and Y, respectively. The size of the N-GQDs slightly increases from the N-GQDs-B, G, and Y. HRTEM images disclose the crystalline nature for all N-GQDs with a lattice space of 0.24 and 0.35 nm, which is corresponding to (1120)14 and (002) of graphite13, respectively. The topographic heights of N-GQDs are mostly between 0.5 nm and 1.5 nm, suggesting that most of N-GQDs are a few layers graphene. Supplementary Fig. S2a shows typical X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns for the as-prepared N-GQDs-B, G, and Y samples. All GQDs show one prominent peak at ∼29°, corresponding to (002) planes of graphite29. In addition, the peak tends to be more and more defined from N-GQDs-B, G, to Y, indicating that the crystalline structure of N-GQDs tends to be perfect and the crystalline domain size increases. FTIR spectra, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2b disclose that the peaks at 3430 and 3289 cm–1 are attributed to the stretch vibration of O-H and N-H, the peaks at 3067 and 2930, 2857 cm–1 contribute from sp2 C-H (C=C-H) and sp3 C-H (C-C-H), respectively17,18. Comparing these three kinds of N-GQDs, the amount of O-H gradually decreases and the amount of N-H, sp2 C-H and sp3 C-H increase from N-GQDs-B, N-GQDs-G to N-GQDs-Y.

TEM, high-resolution HRTEM, and AFM images of N-GQDs with blue (a–c denoted as N-GQDs-B), green (d–f denoted as N-GQDs-G), and yellow (g–i denoted as N-GQDs-Y) emissions, respectively. The insets are the particles size of N-GQDs in diameter (a, d, and g), FFT images in HRTEM images (b, e, and h), and line profile at selected white line in SPM images (c, f, and i).

XPS measurements are employed to uncover the chemical environmental and composition changes. The predominant C1s peak at ∼284 eV, N1s peak at ∼400 eV, and O1s peak at ∼532 eV are observed in the full survey XPS spectra (Figure 2) of N-GQDs-B, G, and Y. The intensity ratio of C/N keeps almost constant. The C to O ratio of N-GQDs-B, G, and Y is 1.36, 2.11, and 3.83, respectively. The increasing ratio of C/O indicates that the amount of oxygen decreases from N-GQDs-B to N-GQDs-Y, which is consistent with the element analysis results. The high-resolution C1s XPS spectra are shown in Figure 2b, 2f, and 2j. The C1s envelope can be split into four Gaussian peaks for N-GQDs-B. Generally, the peak centered at 284.5 eV is assigned to graphitic sp2 C (C-C/C=C), the peaks located at 285.8 and 287.6 eV represent sp3 C (C-C, C-O, C-N), and carbonyl C (C=O), and the peak at 288.5 eV is attributed to the carboxylate C(O)-O30. In the cases of N-GQDs-G and Y, no peak at 288.5 eV is observed, indicating there is no carboxylate group in these N-GQDs samples. That means carboxyl group could be kept in the protic environment (H2O) and hard to be retained in aprotic solution (DMF). The high-resolution N1s XPS spectra (Figure 2c, 2g and 2k) can be fitted into two Gaussian peaks at ∼399.7 and 401.1 eV, which correspond to the pyrrolic N and quaternary N, respectively18,31. The relative amount of pyrrolic N increases and that of quaternary N decreases from N-GQDs-B, N-GQDs-G to N-GQDs-Y samples. That indicates that the pyrrolic ring tends to be formed in aprotic solvent or solvent-free reaction system. Our previous investigation showed the pyrrolic ring formed via dehydrolysis between neighbor carboxyl and amide groups18. The solid 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum demonstrated that the pyrrolic ring belongs to pyrrolidone32,33. With the pyrrolidone formation, the relative amount of carbonyl (C=O) increases, which is consistent with the results of O 1s high-resolution XPS spectra. The peak at 531.7 eV, which is assigned to the carbonyl group, increases from the N-GQDs-B to N-GQDs-G and Y34. The peak at 530.6 eV is attributed from the C=O of quinone, which is from dehydrolysis of neighbor carboxyl groups.

Figure 3 shows the optical images, UV-Vis, PL emission, and PLE spectra of N-GQDs-B, G, and Y. Under normal light, these three kinds of N-GQDs show clear and colorless solution. The UV-Vis spectra show two typical characterized absorption bands at 240 nm and ∼350 nm, Normally, the absorption band at 240 nm is attributed to the π → π* transition of C=C of sp2 C domain in sp3 C matrix23,24. In N-free GQDs, the shoulder at 320–350 nm in the absorption spectra is assigned to the n → π* transition of C=O. That is proved by reduction reaction that this shoulder disappears almost immediately after exposure to hydrazine23,35. In addition, Yang et al. reported that the green emission from oxygen-related function groups is strongly affected by reduction reaction. The charge separation could be observed in the green emission sample20,21. We also carry out the reduction experiment for all kinds of N-GQDs. Both PL and absorption spectra almost have no change before and after addition of NaBH4 into N-GQDs solution (Supplementary Fig. S3). That means this band is not only related to the n → π* transition of C=O but also the transition of conjugated C-N/C=N. Further, EA and XPS results display that the amount of oxygen dramatically decreases in the samples. The ratio of O and C obviously drops down and the ratio of C/N keeps almost same level. High-resolution N 1s XPS spectra disclose that the pyrrolic N amount dramatically increases, which indicates that the edge state of N-GQDs may alter from carboxyl to conjugated pyrrole or pyrrolidone group, called as N state. The absorption band at 350 nm may be attributed to the transition from the highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO) to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMO) of these groups14,33. Comparing the UV-Vis spectra of three kinds of N-GQDs, the adsorption band at 350 nm has a slight red-shift to 360 nm (Figure 3d), indicating that this band affects by the chemical composition of N-GQDs. It should be noted that the intensity ratio of adsorption bands at 240 nm and 350 nm turns from 1.69 for N-GQDs-B to 2.04 for N-GQDs-Y, indicating that the relative amount of sp2 C (C-C/C=C) increases for N-GQDs, which is consistent with the XRD and XPS results. That further demonstrates that the effective conjugation length of GQDs increase from N-GQDs-B, G to Y.

The optical properties of N-GQDs-B, G, and Y. The PL and PLE spectra of N-GQD-B (a), N-GQDs-G (c), N-GQDs-Y (e). The insets are optical images of N-GQDs–B, G, and Y under different excitation wavelengths. The UV-Vis spectra (b) of N-GQDs-B, G, and Y. (d) The lifetime decay of N-GQDs-B, G, and Y. (f) Emission of N-GQDs-B, G, and Y in the CIE 1931 color space.

PL emission and excitation spectra are shown in Figure 3a, 3b and 3c. Each kind of N-GQDs shows blue, green, and yellow emission with narrow full-width-half-maximum height of ∼71, 86, and 111 nm, respectively. In addition, PL emission peaks locate at 450, 550, and 580 nm for N-GQDs-B, G, and Y, respectively, shown in CIE 1931 color space (Figure 3f). All PL spectra of the N-GQDs display slight shift PL emission spectra under different excitation wavelength, implying that both the size and the surface state of those sp2 domains contain in GQDs should be uniform13,19. Although three kinds of N-GQDs show similar UV-Vis spectra, the PLE spectra are dramatically different from each other. The PLE of N-GQDs-B shows two bands at 255 nm and 360 nm which are correlated with the two transitions at 255 nm (4.86 eV) and 360 nm (3.44 eV). The two electronic transitions observed in PLE spectra can be considered as a transition from and HOMO to the LUMO, as shown in Figure 4. The PLE spectra of N-GQDs-G and Y display two excitation bands at 303 (4.09 eV), 444 (2.79 eV), and 320 (3.87 eV), 480 nm (2.58 eV), respectively. The carbene ground-state multiplicity is related to energy differences (δE) between the σ and π orbital. δE should be below 1.5 eV for a triplet ground state36. In our work, the δE for N-GQDs-B, G, and Y are 1.42, 1.30, and 1.29 eV, respectively. These data show that the δEs within required value for triple carbenes. PL emissions and excitation have also ignorable change after reduction by NaBH4 (Supplementary Fig. S3), further indicating that the PL emission may originate from the conjugated pyrrole/pyrrolidone ring. Furthermore, all the PL lifetime of N-GQDs are shown a single exponential decay. The PL decay curves of N-GQDs-B, G, and Y (Figure 3f) derive lifetimes of t = 14, 13, and 10 ns, respectively. They clearly show linear relationship, indicating a single exponential lifetime for the N-GQDs. This demonstrates that the PL emission of N-GQDs originates from a single luminescent species for each N-GQDs. We deduces that the excitation band at 360, 444, and 480 nm may be attributed to the HOMO → LUMO transition of N state for N-GQDs (Scheme). Tunable PL emission can be achieved by controlling the nature of sp2 sites, which depends on the size, shape, and fraction of sp2 domains23. Eda et al. calculated the band gap of aromatic molecules could be decrease from ∼7.0 eV for single benzene ring to 2.0 eV for a cluster of 20 aromatic rings. The red-shift observed in the PLE spectra of N-GQDs-B, G, and Y may be contributed from the growing up of sp2 domain size or effective conjugation length combined with surface groups.

On the basis of the above results, we propose the following PL mechanism (Figure 4). PLE spectra indicate that the PL is contributed from two excitation bands: the π → π* transition of sp2 C and the n → π* transition of N state. For the π → π* transition of sp2 C, The band gap decreases from 4.86 eV to 3.87 eV due to the increasing size of sp2 C cluster in N-GQDs. The contribution of π → π* transition also decreases from N-GQDs-B to N-GQDs-Y due to the larger effective conjugation length and edge state. The edge state of N-GQDs is assigned to N state from conjugated pyrrole/pyrrolidone groups, resulting in a red-shift of PL emission and excitation with the increasing amount of pyrrolic N. Wang et al. also found the introduction of pyrrole ring into GQDs leads to red-shift PL33.

Considering the enormous biomedical application of GQDs, the long wavelength-excited emission is highly desired because that will effectively avoid of bioluminescence. High PL QY of imaging agent is favorable to obtain high contrast bioimaging image. The PL QY of N-GQDs is 90, 29, and 22% for N-GQDs-B, G, and Y with excitation at 360, 450, and 480 nm, respectively. That might be attributed to the chemical nature of N-GQDs. There are less hydroxyl and carboxyl group acting as non-radiative electron-hole recombination center on N-GQDs due to transfer of C-OH and COOH into C-N/C=N and C=C, which leads to a more efficient PL emission37.

The viability of A549 cells was examined after mixing with 0–500 g mL–1 N-GQDs. The investigation of N-GQDs cytotoxicity was carried out using standard MTT assay, as shown in Figure 5d. It is shown that near 100% viability are observed by incubating the A549 cells with N-GQDs for 24 h even at high concentration of N-GQDs like 500 g mL–1. That clearly demonstrates that N-GQDs have a low cytotoxicity and good biocompatibility, indicating that N-GQDs could be potentially used in biological applications such as, bioimaging and biosensing.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy images of A549 cells cultured with N-GQDs for 1 h (3 mg mL–1 of N-GQDs). A549 cells stained with N-GQDs-B (a), N-GQDs-G (b), and N-GQDs-Y (c) under different excitation wavelength. (d) Effect of the concentration of N-GQDs on the viability of A549 cells after 24-h incubation.

To validate the imaging application of N-GQDs, we carried out an in vitro bioimaging study using A549 cells by a confocal fluorescence microscope. After incubation with N-GQDs (3 mg mL–1) at 37 °C for 1 h, the A549 cells under living conditions became brightly illuminated blue, green, and red when imaged under microscope with different excitation wavelength, respectively (Figure 5). The images are collected through blue, green, and red channels of microscopy under 405, 488, and 555 nm light excitation. These results clearly demonstrate the N-GQDs are potential bioimaging agent for in vitro imaging.

Conclusion

We develop a hydrothermal route to synthesize N-doped GQDs with multiple pure color emission by changing reaction solvent. In addition, the solvent changes from protic, aprotic to solvent free, the emission of N-GQDs shifts from blue, green to yellow, respectively. The as-prepared N-GQDs exhibit unique optical properties, for example, tunable color light emission with excitation wavelength-independent and single exponential lifetime decay, indicating that each as-prepared N-GQDs have a single emission center. Although the as-prepared N-GQDs have similar particles size (∼2.5 nm), the difference of PL emission band originates from the different effective conjugation length and edge functional groups of GQDs. In addition, the PLE band also shift from low (350 nm) to high wavelength (480 nm), which will be benefit to the bio-related application. In this report, we demonstrate that N-GQDs could be a potential bioimaging agent for in vitro imaging.

References

Sun YP, Zhou B, Lin Y, Wang W, Fernando KAS et al. Quantum-sized carbon dots for bright and colorful photoluminescence. J Am Chem Soc 2006; 128: 7756–7757.

Baker SN, Baker GA . Luminescent carbon nanodots: emergent nanolights. Angew Chem Int Ed 2010; 49: 6726–6744.

Cao L, Meziani MJ, Sahu S, Sun YP . Photoluminescence properties of graphene versus other carbon nanomaterials. Acc Chem Res 2013; 46: 171–180.

Gonçalves HMR, Duarte AJ, Esteves da Silva JCG . Optical fiber sensor for Hg(II) based on carbon dots. Biosens Bioelectron 2010; 26: 1302–1306.

Yang ST, Cao L, Luo PG, Lu F, Wang X et al. Carbon dots for optical imaging in vivo. J Am Chem Soc 2009; 131: 11308–11309.

Ding C, Zhu A, Tian Y . Functional surface engineering of C-dots for fluorescent biosensing and in vivo bioimaging. Acc Chem Res 2014; 47: 20–30.

Huang P, Lin J, Wang X, Wang Z, Zhang C et al. Light-triggered theranostics based on photosensitizer-conjugated carbon dots for simultaneous enhanced-fluorescence imaging and photodynamic therapy. Adv Mater 2012; 24: 5104–5110.

Zheng M, Liu S, Li J, Qu D, Zhao H et al. Integrating oxaliplatin with highly luminescent carbon dots: an unprecedented theranostic agent for personalized medicine. Adv Mater 2014; 26: 3554–3560.

Zhang X, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Kalytchuk S, Kershaw SV et al. Color-switchable electroluminescence of carbon dot light-emitting diodes. ACS Nano 2013; 7: 11234–11241.

Wang F, Chen YH, Liu CY, Ma DG . White light-emitting devices based on carbon dots’ electroluminescence. Chem Commun 2011; 47: 3502–3504.

Li H, He X, Kang Z, Huang H, Liu Y et al. Water-soluble fluorescent carbon quantum dots and photocatalyst design. Angew Chem Int Ed 2010; 49: 4430–4434.

Yu H, Zhao Y, Zhou C, Shang L, Peng Y et al. Carbon quantum dots/TiO2 composites for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J Mater Chem A 2014; 2: 3344–3351.

Qu D, Zheng M, Du P, Zhou Y, Zhang L et al. Highly luminescent S, N co-doped graphene quantum dots with broad visible absorption bands for visible light photocatalysts. Nanoscale 2013; 5: 12272–12277.

Peng J, Gao W, Gupta BK, Liu Z, Romero-Aburto R et al. Graphene quantum dots derived from carbon fibers. Nano Lett 2012; 12: 844–849.

Zhuo S, Shao M, Lee ST . Upconversion and downconversion fluorescent graphene quantum dots: ultrasonic preparation and photocatalysis. ACS Nano 2012; 6: 1059–1064.

Ye R, Xiang C, Lin J, Peng Z, Huang K et al. Coal as an abundant source of graphene quantum dots. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 2943.

Zhu S, Meng Q, Wang L, Zhang J, Song Y et al. Highly photoluminescent carbon dots for multicolor patterning, sensors, and bioimaging. Angew Chem Int Ed 2013; 52: 3953–3957.

Qu D, Zheng M, Zhang L, Zhao H, Xie Z et al. Formation mechanism and optimization of highly luminescent N-doped graphene quantum dots. Sci Rep 2014; 4: 5294.

Fang Y, Guo S, Li D, Zhu C, Ren W et al. Easy synthesis and imaging applications of cross-linked green fluorescent hollow carbon nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2012; 6: 400–409.

Wang L, Wang HY, Wang Y, Zhu SJ, Zhang YL et al. Direct observation of quantum-confined graphene-like states and novel hybrid states in graphene oxide by transient spectroscopy. Adv Mater 2013; 25: 6539–6545.

Wang L, Zhu SJ, Wang HY, Qu SN, Zhang YL et al. Common origin of green luminescence in carbon nanodots and graphene quantum dots. ACS Nano 2014; 8: 2541–2547.

Xu Q, Zhou Q, Hua Z, Xue Q, Zhang C et al. Single-particle spectroscopic measurements of fluorescent graphene quantum dots. ACS Nano 2013; 7: 10654–10661.

Eda G, Lin YY, Mattevi C, Yamaguchi H, Chen HA et al. Blue photoluminescence from chemically derived graphene oxide. Adv Mater 2010; 22: 505–509.

Liu F, Jang MH, Ha HD, Kim JH, Cho YH et al. Facile synthetic method for pristine graphene quantum dots and graphene oxide quantum dots: origin of blue and green luminescence. Adv Mater 2013; 25: 3657–3662.

Wang L, Zhu SJ, Wang HY, Wang YF, Hao YW et al. Unraveling bright molecule-like state and dark intrinsic state in green-fluorescence graphene quantum dots via ultrafast spectroscopy. Adv Opt Mater 2013; 1: 264–271.

Wen X, Yu P, Toh YR, Hao X, Tang J . Intrinsic and extrinsic fluorescence in carbon nanodots: ultrafast time-resolved fluorescence and carrier dynamics. Adv Opt Mater 2013; 1: 173–178.

Dong Y, Shao J, Chen C, Li H, Wang R et al. Blue luminescent graphene quantum dots and graphene oxide prepared by tuning the carbonization degree of citric acid. Carbon 2012; 50: 4738–4743.

Zheng M, Xie Z, Qu D, Li D, Du P et al. On–off–on fluorescent carbon dot nanosensor for recognition of chromium(VI) and ascorbic acid based on the inner filter effect. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2013; 5: 13242–13247.

Qu S, Wang X, Lu Q, Liu X, Wang L . A biocompatible fluorescent ink based on water-soluble luminescent carbon nanodots. Angew Chem Int Ed 2012; 51: 12215–12218.

Wei D, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhang H, Huang L et al. Synthesis of N-doped graphene by chemical vapor deposition and its electrical properties. Nano Lett 2009; 9: 1752–1758.

Ding W, Wei Z, Chen S, Qi X, Yang T et al. Space-confinement-induced synthesis of pyridinic- and pyrrolic-nitrogen-doped graphene for the catalysis of oxygen reduction. Angew Chem Int Ed 2013; 52: 11755–11759.

Feng R, Zhou W, Guan G, Li C, Zhang D et al. Surface decoration of graphene by grafting polymerization using graphene oxide as the initiator. J Mater Chem 2012; 22: 3982–3989.

Chen S, Hai X, Xia C, Chen XW, Wang JH . Preparation of excitation-independent photoluminescent graphene quantum dots with visible-light excitation/emission for cell imaging. Chem Eur J 2013; 19: 15918–15923.

Wu ZL, Zhang P, Gao MX, Liu CF, Wang W et al. One-pot hydrothermal synthesis of highly luminescent nitrogen-doped amphoteric carbon dots for bioimaging from Bombyx mori silk – natural proteins. J Mater Chem B 2013; 1: 2868–2873.

Lingam K, Podila R, Qian H, Serkiz S, Rao AM . Evidence for edge-state photoluminescence in graphene quantum dots. Adv Funct Mater 2013; 23: 5062–5065.

Bourissou D, Guerret O, Gabbaï FP, Bertrand G . Stable carbenes. Chem Rev 2000; 100: 39–92.

Mei Q, Zhang K, Guan G, Liu B, Wang S et al. Highly efficient photoluminescent graphene oxide with tunable surface properties. Chem Commun 2010; 46: 7319–7321.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21301166, 21201159, 61306081, and 61176016), and Science and Technology Department of Jilin Province (No. 20130522127JH) are gratefully acknowledged. ZS thanks the support of the ‘Hundred Talent Program’ of CAS and Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program of Jilin. The project was supported by Open Research Fund of State Key Laboratory of Polymer Physics and Chemistry and the open research fund program of the State Key Laboratory of Luminescence and Applications.

Note: Accepted article preview online 24 August 2015

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Note: Supplementary Information for this article can be found on the Light: Science & Applications' website .

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Qu, D., Zheng, M., Li, J. et al. Tailoring color emissions from N-doped graphene quantum dots for bioimaging applications. Light Sci Appl 4, e364 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2015.137

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2015.137

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Carbon quantum dots/carbon-coated SnS2 as a high-performance potassium-ion battery cathode material

Ionics (2024)

-

Formation and fluorescent mechanism of red emissive carbon dots from o-phenylenediamine and catechol system

Light: Science & Applications (2022)

-

Ultraviolet phosphorescent carbon nanodots

Light: Science & Applications (2022)

-

Confined-domain crosslink-enhanced emission effect in carbonized polymer dots

Light: Science & Applications (2022)

-

Variant solvothermal synthesis of N-GQD for colour tuning emissions and naked eye reversible shade tweaking pH sensing ability

Chemical Papers (2022)