Abstract

In order to investigate the genetic features of ancient West Siberian people of the Middle Ages, we studied ancient DNA from bone remains excavated from two archeological sites in West Siberia: Saigatinsky 6 (eighth to eleventh centuries) and Zeleny Yar (thirteenth century). Polymerase chain reaction amplification and nucleotide sequencing of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) succeeded for 9 of 67 specimens examined, and the sequences were assigned to mtDNA haplogroups B4, C4, G2, H and U. This distribution pattern of mtDNA haplogroups in medieval West Siberian people was similar to those previously reported in modern populations living in West Siberia, such as the Mansi, Ket and Nganasan. Exact tests of population differentiation showed no significant differences between the medieval people and modern populations in West Siberia. The findings suggest that some medieval West Siberian people analyzed in the present study are included in direct ancestral lineages of modern populations native to West Siberia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

West Siberia is one of the key areas for unveiling the ethnological history in Eurasia, because this land is considered to be the northern boundary between Asia and Europe. The prevalent indigenous populations in the taiga of West Siberia are currently the Ob-Ugrian-speaking Khanty and Mansi, and the Samody-speaking Nenets and Selkups. Turkish Siberian Tatars reside in southern parts of the forest zones. According to their morphological appearance, all of these populations have a combination of European and Asian characteristics. Based on the peculiarity of this combination, some morphological types were grouped previously as Ugrian,1 Ural2, 3 and West Siberian,4 although no genetic evidence is available.

Archeological evidence in West Siberia has showed that the native cultures had been established by the Middle Ages. There are two alternative archeological views on the processes of culture development in the Middle Ages in the forest zones of West Siberia. One point of view concentrates on the evolutionary autochthonous development of indigenous populations, which is expressed in the concept of the Ob-Irtysh historic-cultural community. The Ob-Irtysh community integrated archeological sites in the tundra, taiga and forest-steppe of West Siberia in the fourth to sixteenth centuries. The development of the Ob-Irtysh community was gradual, without revolutionary impact from the outside, leading to the establishment of contemporary native cultures in the onset of the Modern Age.5

Another standpoint focuses attention on immigration into West Siberia during the Middle Ages. Immigration could have changed the cultural, political and economical structures of ancient societies. Supporters of this view point out separate archeological cultures in various periods and areas of West Siberia, and consider some immigrants as ancestors of modern native people.6, 7, 8, 9

Southern parts of West Siberia were included in the Mongol Empire as part of Jochi's Ulus in the twelth century. Since the fourteenth century, most parts of West Siberia until Low Ob were controlled by rulers of the Siberian Khanate. The annexation of this region to Russia began in the sixteenth century. These political processes were accompanied by migrations from metropolitan areas, such as East Asia and Europe.10, 11

The preservation of anthropological materials in the taiga of West Siberia is generally very poor because of the environmental conditions. This has put obstacles in the way of archeological studies of medieval populations; however, some archeological sites have been found in this region, and have given much profitable anthropological information. Human bone remains have also been excavated from two medieval archeological sites in West Siberia (Saigatinsky 6 and Zeleny Yar, dated about 800–1300 years ago). Anthropologists reported that the craniological characteristics of all medieval bones excavated from these archeological sites belong to different varieties of Ural (West Siberian) traits.12

In the present study, to investigate the genetic structure of ancient people in West Siberia, we extracted DNA from bone remains of the medieval West Siberian people, and analyzed haplogroups clarified by nucleotide sequences of hypervariable regions (HVRs) 1 and 2 and single nucleotide polymorphisms distributed in coding regions of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). We discuss the genetic features of the ancient West Siberian people, compared with previously reported data of modern native populations in Siberia.

Materials and methods

Archeological sites

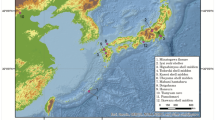

The geographical locations of the two archeological sites (Saigatinsky 6 and Zeleny Yar) are shown in Figure 1.

Graveyard Saigatinsky 6 (61°N 72°E) is located on a bank of the Bolshaja Gnilaja Channel (part of the Ob river system) near Saigatino village. This graveyard is situated in the middle taiga zone in the middle Ob region, where the Khanty lived around this area contemporarily.13 Considerable parts of the necropolis have been excavated by K Karacharov. The burial bone remains are preserved in the Institute of Problems Development of the North, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences. A previous study12 showed that the morphological features of bone remains from Saigatinsky graveyards (sixth to eleventh centuries) were placed between the modern East Khanty and Mansi. In the present study, bone remains from the eighth to eleventh centuries were analyzed.

The funeral complex Zeleny Yar is located on a flood land island between the Polui River and the Gorny Polui Channel (66°N 67°E) near Zeleny Yar village. It consists of graveyards from the eighth to ninth centuries and from the thirteenth century. The site was excavated and comprehensively investigated under the direction of N Fedorova.14 The anthropological materials are preserved in the Institute of History and Archeology, Ural Branch of Russian Academy of Science. The archeological investigation showed a similarity between the necropolis containing medieval graveyards in the North Ob region and contemporary funeral practices in modern North Khanty. The morphological features of bones from Zeleny Yar attributed them to mixed (or intermediate) Ugro-Samody groups living in the north of West Siberia.14

Contamination precautions

The standard contamination precautions were taken according to the previous studies.15, 16

Sample collection

To determine mtDNA haplogroups of the medieval West Siberian people, parts of the skeletal remains of 67 ancient individuals excavated from the above three archeological sites (45 from Saigatinsky 6, 22 from Zeleny Yar) were analyzed.

DNA extraction

The DNA extraction from ancient bones (ribs, patellas, metacarpal bones and skulls) and teeth was carried out according to previous studies.15, 16

PCR amplification and direct sequencing

PCR amplification and direct sequencing were carried out according to the method of the previous study.16 Primer sets L127/H268, L10381/H10466, L16120/H1623917 and A16208/B1640318 were used for PCR amplification. Primers L132 (5′-CCTATGTCGCAGTATCTGTC-3′), H261 (5′-GATGTCTGTGTGGAAAGTGG-3′), L10387 (5′-CCTATGAGTGACTACAAAAGG-3′), H10458 (5′-GAGGGGCATTTGGTAAATATG-3′),16 A16126, B16233, A16214, B1639815 and H1616719 were used for direct sequencing.

Multiplex amplified length polymorphism analysis

To analyze the haplogroup-diagnostic mtDNA single nucleotide polymorphisms of the medieval West Siberian people, the multiplex amplified length polymorphism method of the previous study 20 was used. Using this method, 36 diagnostic mutations (10398A, intergenic COII/tRNALys 9-bp deletion, 5178A, 3010A, 14979C, 8020A, 13104G, 11215T, 11959G, 10400T, 8793C, 4833G, 8200C, 3394C, 14178C, 3970T, 5417A, 13183G, 3594T, 11969A, 11696A, 6455T, 4386C, 12811C, 15487T, 8684T, 1736G, 10873T, 8994A, 4580A, 10550G, 12308G, 1719A, 15607G, 7028C and 12612G) were analyzed. The PCR amplifications and electrophoresis were carried out according to the previous study.16

Data analysis

Nucleotide sequences and single nucleotide polymorphisms of the specimens analyzed in the present study were compared with the revised Cambridge reference sequence,21 and then each specimen was assigned to mtDNA haplogroups according to the mtDNA data and classification tree.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 When any haplogroup classified by HVR motifs was inconsistent with that indicated by the single nucleotide polymorphisms of coding regions, that specimen was excluded from the subsequent data analysis.

To infer the phylogenetic relationships between the medieval West Siberian people and the modern Siberian populations, the previously published data of mtDNA haplogroups from 19 modern and ancient populations were cited as follows: Mansi;28 Ket and Nganasan;29 Itelmen and Koryak;30 Chukuchi and Eskimo;31 Tubalar, Tuvan, Buryat, Tofalar, Evenki, Negidal, Ulchi, Nivkhi and Udegey;32 Khanty;33 Japanese, Chinese and German;21 and ancient Danes.34 The geographic distributions of these populations are shown in Figure 2. The frequencies of mtDNA haplogroups of these populations were compared with those of the medieval West Siberian people obtained in the present study. Pairwise FST values and statistical significance from frequencies of mtDNA haplogroups were computed by ARLEQUIN version 3.11.35 Then, the genetic relationships among the medieval West Siberian people and the modern Siberian populations were analyzed using the neighbor-joining method36 in MEGA version 3.037 and the multidimensional scaling method38 in STATISTICA version 06J (Statsoft JAPAN, Tokyo, Japan) based on pairwise FST values. In addition, principal component analysis based on the distribution pattern of mtDNA haplogroups was carried out using STATISTICA version 06J.

Geographic locations of modern Eurasian populations from the previous studies, compared with the medieval West Siberian people analyzed in the present study. AD, Ancient Danes;34 BR, Buryat; CH, Chukuchi; CN, Chinese; ES, Eskimo;31 EV, Evenki; GM, German; IT, Itelmen; JP, Japanese;20 KH, Khanty;33 KT, Ket; KY, Koryak;30 MN, Mansi;28 NG, Negidal; NS, Nganasan;29 NV, Nivkhi; TB, Tuvan; TF, Tubalar; TV, Tofalar; UD, Udegey;32 UL, Ulchi; WS, medieval West Siberian in the present study, shown by an open circle (Table 2).

Results and discussion

From 13 of 67 specimens examined, fragments of HVR 1 were successfully PCR amplified (Table 1). The following multiplex amplified length polymorphism analysis and HVR 2 sequencing were carried out for the successful 13 specimens. No successful results were obtained from the other 54 specimens because of possible DNA degradation. This significantly low successful rate of mtDNA analysis might have been because the samples analyzed in the present study had been buried in acid soils without coffins. As mtDNA haplogrouping from amplified length polymorphism analysis of 4 (SG6-108west, ZY-9, ZY-10 and ZY-30sk2) of the successful 13 specimens conflicted with that from direct sequencing of HVRs 1 and 2, the haplogroups of the four specimens were not correctly determined. The cause of such inconsistency was considered to be modern DNA contamination or postmortem damage, including deamination of cytosine; therefore, the four specimens were excluded from the subsequent analysis. As a result, mtDNA sequences of nine specimens were finally classified into mtDNA haplogroups (Table 1). The nucleotide sequences of HVRs 1 and 2 as well as nucleotide positions 10 382–10 465 will appear in the DNA databases (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank) with the following accession numbers: AB598647–AB598688.

The mtDNA haplogroups detected from the medieval West Siberian specimens were U, H, G2, C4 and B4 (Table 2). The distribution pattern of the mtDNA haplogroups was similar to those of populations currently living in West Siberia, such as the Mansi and Khanty, and in Central Siberia, such as the Ket and Nganasan (Table 2). The genetic relationships between the medieval West Siberian people and the modern and ancient northern Eurasian populations were shown using the neighbor-joining method (Figure 3). The medieval West Siberian people were located between modern West Siberian populations and modern or ancient European populations. This result might reflect that the medieval West Siberian people analyzed in the present study did not possess both haplogroups I and X, which are specific to European populations, and D, which is specific to Asian populations. The multidimensional scaling method (Figure 4) showed a similar result to the neighbor-joining method. Consequently, genetic distances based on mtDNA haplogroup frequencies between the medieval West Siberian people and the Mansi, Ket, Nganasan or ancient Danes were smaller than those between the medieval West Siberian people and the other populations. The finding suggests that the medieval West Siberian people are genetically closely related to the Mansi currently living in West Siberia, Ket and Nganasan in Central Siberia, or ancient Danes in Scandinavia. This implies that the medieval West Siberian people analyzed in the present study are related to modern native populations of West and Central Siberia, and Scandinavia. In addition, the distribution pattern of eight haplotypes (Types 1–8) of HVR 1 observed among the medieval West Siberian people showed that four were distributed in other populations: Type 2 in ancient Danes, Khanty and Mansi; Type 3 in the Ket, Nganasan and Tubalar; Type 5 in ancient Danes, Khanty, Mansi, Ket and Tubalar; Type 8 in the Ket (Table 3). On the whole, HVR 1 haplotypes observed among the medieval West Siberian people were distributed among northern Europe, and West and Central Siberia. In particular, the distribution pattern of Type 3 was restricted within modern Siberian populations. This could support the suggestion based on the neighbor-joining (Figure 3) and multidimensional scaling methods (Figure 4); however, on the basis of principal component analysis (Figure 5), the medieval West Siberian people seemed to form a cluster together with modern West and Central Siberian populations without European populations. Therefore, the medieval West Siberian people might be closer to modern Siberian populations rather than European populations.

Neighbor-joining relationships among the 22 Eurasian populations on the basis of FST values shown by the scale bar. Abbreviations of populations refer to those in Figure 2. The medieval West Siberian people formed a monophyletic cluster with modern West and Central Siberian populations, including the Mansi, Ket, Nganasan and Khanty, and European populations, including German and Ancient Danes.

Multidimensional scaling on the basis of FST values among the 22 Eurasian populations. Abbreviations of populations refer to those in Figure 2. The medieval West Siberian people (open circle) analyzed in the present study are located between modern West and Central Siberian populations, including the Mansi, Ket, Nganasan and Khanty, and European populations, including German and Ancient Danes.

Principal component analysis based on the distribution pattern of mtDNA haplogroups among the 22 Eurasian populations. Abbreviations of populations refer to those in Figure 2. The medieval West Siberian people (open circle) are located near the modern West Siberian populations including the Mansi, Khanty, Ket and Tubalar.

By contrast, haplogroups V, J, T, K, W, X and D reported in modern West Siberian populations28, 29, 30, 31, 32 were not identified from the medieval West Siberian people in the present study (Table 2). In addition, haplogroup I reported in ancient and modern European populations22, 34 was not detected from medieval West Siberians in the present study (Table 2). These genetic differences between medieval West Siberian people and modern West and Central Siberian populations or European populations might be attributed to the small number of medieval West Siberian specimens successfully analyzed in the present study. Alternatively, haplogroups V, J, T, K, W, X and D were probably brought to ancestors of the native West Siberian populations via recent gene flows from Europe (for V, J, T, K, W and X) and Central Siberia (for D), and haplogroup I was probably lost during the migration from Europe to West Siberia by the founder effect. Frequencies of haplogroups V, W and X were significantly low even in West Siberian and European populations compared with medieval West Siberian people in the present study (Table 2); therefore, even if these haplogroups existed in medieval West Siberian people, it was difficult to detect them from the small number of samples, such as bone remains, analyzed in the present study. Although haplogroups J, T and D are distributed among modern West Siberian populations at relatively high frequencies, it also seemed difficult to detect them from these nine samples. When the nine individuals were sampled at random from the 47 individuals of the Khanty that possess haplogroup J at the highest frequency among West Siberian populations used for comparison in the present study, the probability of any individuals with haplogroup J not being sampled was ∼0.20, not statistically significant. This means it is possible that haplogroup J was undetected from the nine specimens of medieval West Siberian population, even if this haplogroup existed among them at equal frequency to the Khanty. Similarly, in the case of haplogroup T for the 98 individuals of the Mansi, the probability was ∼0.49, also not significant. In the case of haplogroup D for the 47 individuals of the Khanty, the probability was ∼0.20, also not significant; therefore, the reason why these haplogroups were not detected from the specimens analyzed in the present study must be the issue of sample size. On the other hand, in the case of haplogroup D for 24 individuals of the Nganasan, the probability was ∼0.03, significantly low; therefore, even if haplogroup D existed in medieval West Siberian people, the frequency would be different between medieval West Siberian people and Nganasan. Perhaps the genetic structure might be slightly different between the Nganasan and medieval West Siberian people, although the FST value between them was extremely small. At least, the population differentiation between the medieval West Siberian people and modern West Siberian populations was not statistically significant (P>0.05). The results suggest that the influence of gene flow to native West Siberian populations until modern times was not so strong.

In conclusion, the present study implied that medieval West Siberian people were closely related to populations currently living in Siberia. This indicates that the ancient West Siberian people of the Middle Ages could be relatives of modern native populations living in West and Central Siberia, although some migration to native West Siberian people might have occurred; however, because the sample size in the present study was extremely small, the results were not statistically significant. To resolve this statistical issue, additional samples that have been preserved in good condition in West Siberia must be analyzed. In addition, to further understand the genetic features and history of the ancient West Siberian people, information on the paternal and biparental gene lineages as well as additional ancestors from different periods would be very useful; however, the low rate of the successful samples analyzed in the present study may indicate the difficulty of obtaining nucleic DNA data, as reported in some previous studies.39, 40

Accession codes

References

Deniker, J. Races of Man: An Outline of Anthropology and Ethnography 2nd edn (The Walter Scott Publishing, New York, 1900).

Bunak, V. V. Human race and ways of its origins. Sovet Ethnogr 1, 86–105 (1956) (in Russian).

Davydova, G. M. in On the Issue of Anthropology of Ural Race (eds Gokhman, I. I. & Yusupov, R. M.) 5–14 (Baschkir Scientific Center Ural Branch of Russian Academy of Science, Ufa, 1992) (in Russian).

Bagashev, A. N. in The Essays of Culturegenesis of Population of West Siberia - T. 4. Rasogenesis of Native Population (ed. Bagashev, A. N.) 304–327 (Tomsk State University, Tomsk, 1998) (in Russian).

Zykov, A. P. in Archaeological Heritage of Yugra (eds Stefanov, V. I. & Perevalova, E. V.) 109–125 (Charoid, Ekaterinburg, Khanty-Mansiisk, 2006) (in Russian with English abstract).

Konnikov, B. A. Taiga Zone of Irtysh Region in X–XIII A. D. (Omsk State Teachers’ Training Institute, Omsk, 1993) (in Russian).

Khlobystin, L. P. Ancient History of Arctic Taimyr and Questions of Forming Cultures in North Eurasia (Dmitry Bulanin, Saint-Petersburg, 1998) (in Russian).

Chemyakin, Yu.P., Karacharov, K. G., Glavatzkaya, E. M., Dmitrieva, T. N. & Wiget, A. Essays on Traditional Land Tenure of Khanty (Tesis, Ekaterinburg, 2002) (in Russian).

Chihdina, L. A. The History of Middle Ob Region in Early Middle Age (Tomsk State University, Tomsk, 1991) (in Russian).

Faizrakhmanov, G. L. The History of Siberian Tatar (Fan, Kazan, 2002) (in Russian).

Preobrazhenskiy, A. A. Ural and West Siberia in End of XVI – Beginning of XVII Cent (Nauka, Moscow, 1972) (in Russian).

Bagashev, A. N. & Poshekhonova, O. E. Anthropological composition and origin problems medieval population of Middle Ob region. Bull Archaeol Anthropol Ethnogr 8, 87–96 (2007) (in Russian with English abstract).

Aksyanova, G. A. & Sokolova, Z. P. in Folks of West Siberia (eds Gemuev, I. N., Molodin, W. I. & Sokolova Z. P.) 57–67 (Nauka, Moscow, 2005) (in Russian).

Aleksashenko, N. A., Brusnitsyna, A. G., Litvinenko, M. N., Kosintzev, P. A., Perevalova, E. V., Razhev, D. I. et al. in Zeleny Yar: Archeological Site of Middle Age in Region of North Ob. UrO RAN (ed. Fedorova, N. V.) 368 (Ekaterinburg, Salekhard, 2005) (in Russia with English abstract).

Sato, T., Amano, T., Ono, H., Ishida, H., Kodera, H., Matsumura, H. et al. Origins and genetic features of the Okhotsk people, revealed by ancient mitochondrial DNA analysis. J. Hum. Genet. 52, 618–627 (2007).

Sato, T., Amano, T., Ono, H., Ishida, H., Kodera, H., Matsumura, H. et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogrouping of the Okhotsk people based on analysis of ancient DNA: an intermediate of gene flow from the continental Sakhalin people to the Ainu. Anthropol. Sci. 117, 171–180 (2009).

Adachi, N., Umetsu, K., Takigawa, W. & Sakaue, K. Phylogenetic analysis of the human ancient mitochondrial DNA. J. Archaeol. Sci. 31, 1339–1348 (2004).

Horai, S., Hayasaka, K., Murayama, K., Wate, N., Koike, H. & Nakai, N. DNA amplification from ancient human skeletal remains and their sequence analysis. Proc. Jpn. Acad. 65, 229–233 (1989).

Ricaut, F. X., Keyser-Tracqui, C., Bourgeois, J., Crubezy, E. & Ludes, B. Genetic analysis of a Sctho-Siberian skeleton and its implications for ancient Central Asian migrations. Hum. Biol. 76, 109–125 (2004).

Umetsu, K., Tanaka, M., Yuasa, I., Adachi, N., Miyoshi, A., Kashimura, S. et al. Multiplex amplified product-length polymorphism analysis of 36 mitochondrial single-nucleotide polymorphisms for haplogrouping of East Asian populations. Electrophoresis 26, 91–98 (2005).

Andrews, R. M., Kubacka, I., Chinnery, P. F., Lightowlers, R. N., Turnbull, D. M. & Howell, N. Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 23, 147 (1999).

Finnilä, S., Lehtonen, M. S. & Majamaa, K. Phylogenetic network for European mtDNA. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 1475–1484 (2001).

Kivisild, T., Tolk, H. V., Parik, J., Wang, Y., Papiha, S. S., Bandelt, H. J. et al. The emerging limbs and twigs of the East Asian mtDNA tree. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 1737–1751 (2002).

Yao, Y. G., Kong, Q. P., Bandelt, H. J., Kivisild, T. & Zhang, Y. P. Phylogenetic differentiation of mitochondrial DNA in Han Chinese. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 635–651 (2002).

Kong, Q. P., Yao, Y. G., Sun, C., Bandelt, H. J., Zhu, C. L. & Zhang, Y. P. Phylogeny of East Asian mitochondrial DNA lineages inferred from complete sequences. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73, 671–676 (2003).

Kong, Q. P., Bandelt, H. J., Sun, C., Yao, Y. G., Salas, A., Achilli, A., et al., Zhang, Y. P. Updating the East Asian mtDNA phylogeny: a prerequisite for the identification of pathogenic mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 2076–2086 (2006).

Maruyama, S., Minaguchi, K. & Saitou, N. Sequence polymorphisms of the mitochondrial DNA control region and phylogenetic analysis of mtDNA lineages in the Japanese populations. Int. J. Legal. Med. 117, 218–225 (2003).

Derbeneva, O. A., Starikovskaya, E. B., Wallace, D. C. & Sukernik, R. I. Traces of early Eurasians in the Mansi of northwest Siberia revealed by mitochondrial DNA analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 1009–1014 (2002).

Derbeneva, O. A., Starikovskaya, E. B., Volodko, N. V., Wallace, D. C. & Sukernik, R. I. Mitochondrial DNA variation in Kets and Nganasans and the early peopling of Northern Eurasia. Genetika (Rus. J. Genet.) 38, 1554–1560 (2002).

Schurr, T. G., Sukernik, R. I., Starikovskaya, Y. B. & Wallace, D. C. Mitochondrial DNA variation in Koriaks and Itel’men: population replacement in the Okhotsk Sea-Bering Sea region during the Neolithic. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 108, 1–42 (1999).

Starikovskaya, Y. B., Sukernik, R. I., Schurr, T. G., Kogelnik, A. & Wallace, D. C. Mitochondrial DNA diversity in Chukuchi and Siberian Eskimos: implications for the genetic history of ancient Beringia and the peopling of the New World. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 63, 1473–1491 (1998).

Starikovskaya, E. B., Sukernik, R. I., Derbeneva, O. A., Volodko, N. V., Ruiz-Pesini, E., Torroni, A. et al. Mitochondrial DNA diversity in indigenous populations of southern extent of Siberia, and the origins of native American haplogroups. Ann. Hum. Genet. 69, 67–89 (2005).

Naumova, O. Y., Khayat, S. S. & Rychov, S. Y. Mitochondrial DNA diversity in Kazym Khanty. Rus. J. Genet. 45, 756–760 (2009).

Melchior, L., Lynnerup, N., Siegismund, H. S., Kivisild, T. & Dissing, J. Genetic diversity among ancient Nordic populations. Plos. One. 5, 1–9 (2010).

Excoffier, L., Laval, G. & Schneider, S. Arelequin ver. 3.0: an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinform. Online 1, 47–50 (2005).

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987).

Kumar, S., Tamura, K. & Nei, M. MEGA 3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5, 150–163 (2004).

Sneath, P. H. A. & Sokal, R. R. Numerical taxonomy. Nature 193, 855–860 (1962).

Keyser, C., Bouakaze, C., Crubézy, E., Nikolaev, V. G., Montagnon, D., Reis, T. et al. Ancient DNA provides new insight into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people. Hum. Genet. 126, 395–410 (2009).

Crubézy, E., Amory, S., Keyser, C., Bouakaze, C., Bodner, M., Gibert, M. et al. Human evolution in Siberia: from frozen bodies to ancient DNA. BMC. Evol. Biol. 10, 1471–2148 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank K Karacharov and N Fedorova for giving us the chance to study anthropological materials, A Bagashev for anthropological suggestions and H Kazuta for support with the statistical analysis. This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid-for Scientific Research (No. 21401023) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and a Grant 10-06-00045-a ‘Craniological peculiarity, adaptive resources and constitution of native populations of taiga zone of West Siberia’ from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, T., Razhev, D., Amano, T. et al. Genetic features of ancient West Siberian people of the Middle Ages, revealed by mitochondrial DNA haplogroup analysis. J Hum Genet 56, 602–608 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2011.68

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2011.68