Abstract

To examine genetic affinity among Oceanian populations, polymorphisms of exons six and seven of the ABO blood group gene (ABO) were investigated in three populations—Munda town, Paradise village, and Rawaki village—in the New Georgia group of the Solomon Islands. The Munda and Paradise populations consist of Austronesian (AN)-speaking Melanesians; the Rawaki population consists of AN-speaking Micronesians who migrated from the Gilbert Islands to the New Georgia Islands approximately 30 years ago. We recently described the polymorphisms of ABO in three other Oceanian populations—Balopa Islanders (AN-speaking Melanesians), Gidra (non-AN-speaking Melanesians), and Tongans (AN-speaking Polynesians). The results from these six Oceanian populations suggest: (1) the main alleles in Oceanian populations are ABO*A101, ABO*A102, ABO*B101, ABO*O01, and ABO*O02, among which the most predominant is ABO*O01, and (2) there are marked differences in the ABO allele frequency spectrum among Oceanian populations. The different geographical distribution of ABO alleles provides insight into the migration history of AN-speaking populations in Oceania.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ABO blood group gene (ABO) has high polymorphism at the molecular level (see Yip (2002) for review), and the allele frequency distribution of ABO differs among populations (Ogasawara et al. 1996; Olsson et al. 1998; Kobayashi et al. 1999; Iwasaki et al. 2000; Roubinet et al. 2001; Ohashi et al. 2004). Because of these characteristics, the ABO gene can serve as a genetic marker suitable for studying genetic affinity among populations.

We recently described the polymorphisms of ABO in three Oceanian populations:

-

1

Austronesian (AN)-speaking Melanesians in the Balopa islands of Manus Province of Papua New Guinea, located at the northwestern end of the Bismarck Archipelago;

-

2

non-Austronesian (NAN)-speaking Melanesians, known as Gidra, in the southwestern lowlands of Papua New Guinea; and

-

3

AN-speaking Polynesians living in Tonga.

It has been suggested that the AN-speaking groups who are ancestors of the Polynesian appeared at the main island of New Guinea approximately 5,000 years ago and moved eastward along the northern coast to the Bismarck Archipelago. Before the appearance of the AN-speaking groups, many islands of Melanesia, for example the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon islands had been occupied by NAN-speaking Melanesians. The AN-speaking groups are, therefore, believed to have come into contact with NAN-speaking Melanesians in Near Oceania. The extent of admixture between the AN-speaking newcomers and indigenous Melanesians is not fully understood, however. From ABO allele frequency data we concluded that Balopa Islanders, who are thought to be descendants of the indigenous Melanesians, were genetically more similar to the Polynesian Tongans than to the NAN-speaking Melanesian Gidra (Ohashi et al. 2004). Another finding of our previous study was that ABO*A102 is useful for distinguishing AN-speaking groups from NAN-speaking groups in Melanesia, because this allele was found in Balopa Islanders and Tongans (AN-speaking Melanesians and Polynesians) but not in Gidra (NAN-speaking Melanesians) (Ohashi et al. 2004). ABO*A102 has been reported to be a predominant ABO*A allele in East Asian populations—the allele frequencies of ABO*A101 and ABO*A102 are 2.3 and 18.6% in Han and 4.4 and 23.5% in Japanese populations (Ogasawara et al. 1996; Iwasaki et al. 2000). Because the AN-speaking groups are believed to have come from Asia/Taiwan, this allele may have been brought to island Melanesia by them.

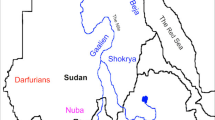

As far as we are aware, however, ABO polymorphisms have not been analyzed in other Oceanian populations. Thus, more Oceanian populations should be examined to enable comprehensive understanding of ABO polymorphism and genetic admixture in Oceania. To achieve this goal, we investigated polymorphisms of ABO exons six and seven in three populations (Fig. 1)—Munda town, Paradise village, and Rawaki village in the New Georgia group of the Solomon Islands. The Munda and Paradise populations are AN-speaking Melanesians and the Rawaki population are AN-speaking Micronesians who migrated from the Gilbert Islands, Kiribati, to the New Georgia Islands, Solomon, approximately 30 years ago. These results also have implications in the study of migration history, especially of AN-speaking groups.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The polymorphisms of the ABO blood group gene were investigated for 39 individuals living in Munda town, 46 in Paradise village, and 46 in Rawaki village. These locations are shown in Fig. 1. Munda is the main town on New Georgia Island in the western Solomon Islands. Paradise is a coastal village, 32 km north of Munda. The Paradise villagers are thought to have originally lived in a mountainous area and moved to the northern coast of New Georgia Island. Rawaki village is located on the New Georgia Islands, but Rawaki villagers are AN-speaking Micronesians who migrated from the Gilbert Islands, Kiribati, to the New Georgia Islands approximately 30 years ago. Thus, in this study, two AN-speaking Melanesian populations and one AN-speaking Micronesian population were investigated. Blood was sampled after obtaining informed written consent from each participant. This study was approved by the Health Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health, Solomon Islands, the Ministry of Education and Training, Solomon Islands, and the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, The University of Tokyo.

Molecular typing of ABO gene

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using a QIAamp Blood Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genotyping for exons six and seven of the ABO gene was performed as described previously (Ohashi et al. 2004). As in our previous study, we performed both gel electrophoresis-based typing and direct sequencing for all the subjects to determine the genotypes.

Statistical analysis

Allele frequencies of the ABO gene were estimated by direct counting. The ABO allele frequency data for Balopa Islanders, Gidra, and Tongans were obtained from our previous study (Ohashi et al. 2004). To examine genetic affinities based on ABO allele frequencies, Arlequin software (Schneider et al. 2000) was used for calculation of population pairwise fixation indices (FST values), which were subsequently tested for significance. The neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed for six populations based on the pairwise FST values. Principal components (PC) analysis was also performed to examine genetic affinities among the six Oceanian populations.

Results

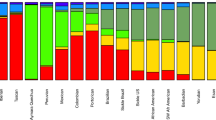

The ABO allele frequencies for the Munda, Paradise, and Rawaki populations are presented in Table 1. As in our previous study of Oceanian populations (Ohashi et al. 2004), five ABO alleles (ABO*A101, ABO*A102, ABO*B101, ABO*O01, and ABO*O02) were observed (Fig. 2), although the frequency distribution differed among populations. Interestingly, approximately 95% of ABO alleles in Paradise village were ABO*O01 or ABO*O02. The Paradise population is believed to have been both small and isolated. Thus, the observed high frequency of ABO*O alleles in Paradise may have been caused by random genetic drift or a founder effect.

Figure 3 shows the geographic distribution of the ABO alleles in Oceanian populations, with data for Gidra, Balopa Islanders, and Tongans from our previous study (Ohashi et al. 2004). The ABO allele frequencies in the Munda population were similar to those in the Balopa population, which was expected because both groups are AN-speaking Melanesians. The allele frequency of ABO*B101 was found to be high in the Rawaki population. It would be interesting to study the polymorphisms of ABO in other Micronesian populations to examine whether the high frequency of ABO*B101 is a general characteristic of Micronesians.

Map displaying the geographic distribution of ABO alleles in Oceania. It should be noted that Rawaki villagers migrated from the Gilbert Islands, Kiribati, to the New Georgia Islands 30 years ago. They should, therefore, be genetically regarded as Micronesians. The data for Gidra, Balopa Islanders, and Tongans were obtained from our previous study (Ohashi et al. 2004)

Pairwise FST values were calculated as a measure of genetic distance (Table 2). The highest FST value of 0.221 (P<10−5) was observed between Rawaki and Paradise villagers. For Munda villagers small pairwise FST values of 0.014, 0.012, and 0.017 were obtained for Gidra, Balopa Islanders, and Tongans, respectively. Nevertheless, a relatively large FST value of 0.081 (P<10−5) was obtained between Munda and Paradise villagers, although they are AN-speaking Melanesians and they live close to each other. This may suggest that significant migration or admixture has not occurred for Munda and Paradise villagers. An NJ tree based on pairwise FST values is shown in Fig. 4a. In the tree, Munda was located between Gidra and Tongan populations whereas the Paradise and Rawaki populations were situated apart from the other populations.

a An NJ tree for the six populations based on pairwise FST. b Results from PC analysis for the six populations based on the ABO allele frequency distribution. The contributions of the first and second dimensions were 0.686 and 0.229, respectively. The data for Gidra, Balopa Islanders, and Tongans were obtained from our previous study (Ohashi et al. 2004)

Figure 4b shows results from PC analysis of ABO allele frequencies. Each population is plotted in two dimensions based on the coordinates of the two PCs. The contributions of the first and second components were 0.686 and 0.229, respectively (the cumulative contribution was 0.915). As in the NJ tree, Munda was genetically placed between the Gidra and Tongan populations.

Discussion

Polymorphisms of ABO were studied for three populations living in the New Georgia group of the Solomon Islands. Taking these results together with those from our previous study (Ohashi et al. 2004), we conclude that:

-

1

the main alleles in Oceanian populations are ABO*A101, ABO*A102, ABO*B101, ABO*O01, and ABO*O02, among which the predominant ABO allele in Oceanian populations is ABO*O01; and

-

2

there is marked difference in the ABO allele frequency spectrum among Oceanian populations. The variety of ABO alleles in Oceanian populations enables us to use it as a genetic marker for studying the history of Oceanian populations.

Melanesians can be divided into two groups—AN-speaking and NAN-speaking—on the basis of their languages. It has been suggested that AN-speaking groups are derived from Southeast Asians who reached the main island of New Guinea approximately 5,000 years ago and, by approximately 3,000 years ago, spread into island Melanesia including the Solomon Islands, New Hebrides Islands, and Fiji Islands, and further into western Polynesian islands, for example Tonga and Samoa. Before the AN-speaking populations appeared, the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon Islands had already been occupied by NAN-speaking populations whose ancestors had come to Papua New Guinea approximately 50,000 years ago. In studies on the history of Oceanian populations, much attention has been focused on the mixing between AN-speaking and NAN-speaking groups in Melanesia. Our previous studies on the ABO and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) polymorphisms suggested that extensive gene flow occurred from Polynesian ancestors to indigenous Melanesians, because Balopa Islanders (AN-speaking Melanesians) were genetically similar to Tongans (AN-speaking Polynesians) rather than to Gidra (NAN-speaking Melanesians) (Ohashi et al. 2004; Ohashi et al. in press). Thus, the “express train” model, which supposes rapid expansion of Polynesian ancestors along the coast of New Guinea to Polynesia and negligible mixing with indigenous Melanesians (Diamond 1988; Bellwood 1989), is not compatible with our observation for Balopa Islanders of the Bismarck Archipelago. In this study, two AN-speaking populations, Munda and Paradise, in the Solomon Islands were examined, and the Munda population was genetically placed between the Gidra and Tongan populations (Fig. 4). This is also supported by mtDNA polymorphisms (our unpublished data). These results lead us to hypothesize that mixing between Polynesian ancestors and indigenous Melanesians occurred not only in the Bismarck Archipelago, but also in the Solomon Islands.

Among these six Oceanian populations, only the Gidra (NAN-speaking Melanesians) seem to lack the ABO*A102 allele (Fig. 3). Thus, ABO*A102 might be a genetic marker distinguishing AN-speaking groups from NAN-speaking groups in Melanesia. The ABO*A102 allele in AN-speaking groups in Oceania may have been derived mainly from Polynesian ancestors who presumably had migrated from Asia/Taiwan, although this allele may have been lost in Gidra only, after the ancestors of Gidra had come to Papua New Guinea. To examine this, ABO polymorphisms need to be investigated in more NAN-speaking Melanesian populations.

References

Bellwood PS (1989) The colonization of the Pacific: some current hypotheses. In: Hill AVS, Sergeantson SW (eds) The colonization of the pacific: a genetic trail. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp1–59

Diamond JM (1988) Express train to polynesia. Nature 336:307–308

Iwasaki M, Kobayashi K, Suzuki H, Anan K, Ohno S, Geng Z, Li G, Inoko H (2000) Polymorphism of the ABO blood group genes in Han, Kazak and Uygur populations in the silk route of northwestern China. Tissue Antigens 56:136–142

Kobayashi K, Iwasaki M, Anan K, Suzuki Y, Suzuki H, Tamai S, Saitou N (1999) An analysis of polymorphisms for the ABO blood group genes in a Japanese population based on polymerase chain reaction. Anthropol Sci 107:109–121

Ogasawara K, Bannai M, Saitou N, Yabe R, Nakata K, Takenaka M, Fujisawa K, Uchikawa M, Ishikawa Y, Juji T, Tokunaga K (1996) Extensive polymorphism of ABO blood group gene: three major lineages of the alleles for the common ABO phenotypes. Hum Genet 97:777–783

Ohashi J, Naka I, Ohtsuka R, Inaoka T, Ataka Y, Nakazawa M, Tokunaga K, Matsumura Y (2004) Molecular polymorphism of ABO blood group gene in Austronesian and Non-Austronesian populations in Oceania. Tissue Antigens 63:355–361

Ohashi J, Naka I, Tokunaga K, Inaoka T, Ataka Y, Nakazawa M, Matsumura Y, Ohtsuka R Mitochondrial DNA variation suggests extensive gene flow from Polynesian ancestors to indigenous Melanesians in the northwestern Bismarck archipelago. Am J Phys Anthropol (in press)

Olsson ML, Santos SE, Guerreiro JF, Zago MA, Chester MA (1998) Heterogeneity of the O alleles at the blood group ABO locus in Amerindians. Vox Sang 74:46–50

Roubinet F, Kermarrec N, Despiau S, Apoil PA, Dugoujon JM, Blancher A (2001) Molecular polymorphism of O alleles in five populations of different ethnic origins. Immunogenetics 53:95–104

Schneider S, Roessli D, Excoffier L (2000) Arlequin version 2.000: a software for population genetic data analysis, Genetics and Biometry Laboratory, University of Geneva, Switzerland

Yip SP (2002) Sequence variation at the human ABO locus. Ann Hum Genet 66:1–27

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the people of the New Georgia group of the Solomon Islands for their kind cooperation in providing blood samples for testing. We thank chiefs, elders, and church leaders in the participating communities, especially Sir. Ikan Rove of the Christian Fellowship Church, for their understanding and permission for the research. Thanks are also due to Helena Goldie Hospital, Munda, Western Province, the Solomon Islands, and Gizo Hospital, Gizo, Western Province, the Solomon Islands, for help in collecting and storing the blood samples. We also thank Dr George Malefoasi, undersecretary of the Ministry of Health, the Solomon Islands, and Mr James Pada, Helena Goldie Hospital, Munda, Western Province, the Solomon Islands for supporting the research. We thank two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments and suggestions about a previous Version of this manuscript. This study was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ohashi, J., Naka, I., Kimura, R. et al. Polymorphisms in the ABO blood group gene in three populations in the New Georgia group of the Solomon Islands. J Hum Genet 51, 407–411 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10038-006-0375-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10038-006-0375-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Admixture with indigenous people helps local adaptation: admixture-enabled selection in Polynesians

BMC Ecology and Evolution (2021)

-

Hypertension-susceptibility gene prevalence in the Pacific Islands and associations with hypertension in Melanesia

Journal of Human Genetics (2013)

-

Polymorphisms and allele frequencies of the ABO blood group gene among the Jomon, Epi-Jomon and Okhotsk people in Hokkaido, northern Japan, revealed by ancient DNA analysis

Journal of Human Genetics (2010)

-

The Q223R polymorphism in LEPR is associated with obesity in Pacific Islanders

Human Genetics (2010)

-

FTO polymorphisms in oceanic populations

Journal of Human Genetics (2007)