Abstract

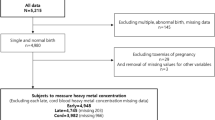

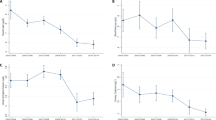

There is an emerging hypothesis that exposure to cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), lead (Pb), and selenium (Se) in utero and early childhood could have long-term health consequences. However, there are sparse data on early life exposures to these elements in US populations, particularly in urban minority samples. This study measured levels of Cd, Hg, Pb, and Se in 50 paired maternal, umbilical cord, and postnatal blood samples from the Boston Birth Cohort (BBC). Maternal exposure to Cd, Hg, Pb, and Se was 100% detectable in red blood cells (RBCs), and there was a high degree of maternal–fetal transfer of Hg, Pb, and Se. In particular, we found that Hg levels in cord RBCs were 1.5 times higher than those found in the mothers. This study also investigated changes in concentrations of Cd, Hg, Pb, and Se during the first few years of life. We found decreased levels of Hg and Se but elevated Pb levels in early childhood. Finally, this study investigated the association between metal burden and preterm birth and low birthweight. We found significantly higher levels of Hg in maternal and cord plasma and RBCs in preterm or low birthweight births, compared with term or normal birthweight births. In conclusion, this study showed that maternal exposure to these elements was widespread in the BBC, and maternal–fetal transfer was a major source of early life exposure to Hg, Pb, and Se. Our results also suggest that RBCs are better than plasma at reflecting the trans-placental transfer of Hg, Pb, and Se from the mother to the fetus. Our study findings remain to be confirmed in larger studies, and the implications for early screening and interventions of preconception and pregnant mothers and newborns warrant further investigation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Thayer KA, Heindel JJ, Bucher JR, Gallo MA . Role of environmental chemicals in diabetes and obesity: a National Toxicology Program workshop review. Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120: 779–789.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Toxicological profile for mercury, 1999, pp 1–676.

Sikorski R, Paszkowski T, Szprengier-Juszkiewicz T . Mercury in neonatal scalp hair. Sci Total Environ 1986; 57: 105–110.

Lucas M, Dewailly E, Muckle G, Ayotte P, Bruneau S, Gingras S et al. Gestational age and birth weight in relation to n-3 fatty acids among Inuit (Canada). Lipids 2004; 39: 617–626.

Foldspang A, Hansen JC . Dietary intake of methylmercury as a correlate of gestational length and birth weight among newborns in Greenland. Am J Epidemiol 1990; 132: 310–317.

Goyer RA . Transplacental transport of lead. Environ Health Perspect 1990; 89: 101–105.

Chen PC, Pan IJ, Wang JD . Parental exposure to lead and small for gestational age births. Am J Ind Med 2006; 49: 417–422.

Rayman MP, Wijnen H, Vader H, Kooistra L, Pop V . Maternal selenium status during early gestation and risk for preterm birth. CMAJ 2011; 183: 549–555.

Arai Y, Ohgane J, Yagi S, Ito R, Iwasaki Y, Saito K et al. Epigenetic assessment of environmental chemicals detected in maternal peripheral and cord blood samples. J Reprod Dev 2011; 57: 507–517.

Hanna CW, Bloom MS, Robinson WP, Kim D, Parsons PJ, vom Saal FS et al. DNA methylation changes in whole blood is associated with exposure to the environmental contaminants, mercury, lead, cadmium and bisphenol A, in women undergoing ovarian stimulation for IVF. Hum Reprod 2012; 27: 1401–1410.

Zahir F, Rizwi SJ, Haq SK, Khan RH . Low dose mercury toxicity and human health. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2005; 20: 351–360.

Grandjean P, Weihe P, White RF, Debes F, Araki S, Yokoyama K et al. Cognitive deficit in 7-year-old children with prenatal exposure to methylmercury. Neurotoxicol Teratol 1997; 19: 417–428.

Jusko TA, Henderson CR, Lanphear BP, Cory-Slechta DA, Parsons PJ, Canfield RL . Blood lead concentrations<10 mu g/dl and child intelligence at 6 years of age. Environ Health Perspect 2008; 116: 243–248.

Satarug S, Baker JR, Urbenjapol S, Haswell-Elkins M, Reilly PE, Williams DJ et al. A global perspective on cadmium pollution and toxicity in non-occupationally exposed population. Toxicol Lett 2003; 137: 65–83.

He K, Xun P, Liu K, Morris S, Reis J, Guallar E . Mercury exposure in young adulthood and incidence of diabetes later in life: the CARDIA trace element study. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 1584–1589.

Navas-Acien A, Guallar E, Silbergeld EK, Rothenberg SJ . Lead exposure and cardiovascular disease—a systematic review. Environ Health Perspect 2007; 115: 472–482.

Bleys J, Navas-Acien A, Guallar E . Serum selenium and diabetes in US adults. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 829–834.

Mestan K, Yu Y, Matoba N, Cerda S, Demmin B, Pearson C et al. Placental inflammatory response is associated with poor neonatal growth: preterm birth cohort study. Pediatrics 2010; 125: e891–e898.

Wells EM, Jarrett JM, Lin YH, Caldwell KL, Hibbeln JR, Apelberg BJ et al. Body burdens of mercury, lead, selenium and copper among Baltimore newborns. Environ Res 2011; 111: 411–417.

Jones EA, Wright JM, Rice G, Buckley BT, Magsumbol MS, Barr DB et al. Metal exposures in an inner-city neonatal population. Environ Int 2010; 36: 649–654.

Dietrich KN, Douglas RM, Succop PA, Berger OG, Bornschein RL . Early exposure to lead and juvenile delinquency. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2001; 23: 511–518.

Ernhart CB, Morrow-Tlucak M, Marler MR, Wolf AW . Low level lead exposure in the prenatal and early preschool periods: early preschool development. Neurotoxicol Teratol 1987; 9: 259–270.

Bellinger D, Leviton A, Waternaux C, Needleman H, Rabinowitz M . Longitudinal analyses of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 1037–1043.

Sakamoto M, Chan HM, Domingo JL, Kubota M, Murata K . Changes in body burden of mercury, lead, arsenic, cadmium and selenium in infants during early lactation in comparison with placental transfer. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2012; 84: 179–184.

Kumar R, Ouyang F, Story RE, Pongracic JA, Hong X, Wang G et al. Gestational diabetes, atopic dermatitis, and allergen sensitization in early childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124: 1031–8 e1-4.

CDC. Laboratory Procedure Manual: Lead and Cadmium in Whole Blood. Division of Laboratory Sciences National Center for Environmental Health: Atlanta, GA. 2008.

Wang G, Divall S, Radovick S, Paige D, Ning Y, Chen Z et al. Preterm birth and random plasma insulin levels at birth and in early childhood. JAMA 2014; 311: 587–596.

deSilva PE . Determination of lead in plasma and studies on its relationship to lead in erythrocytes. Br J Ind Med 1981; 38: 209–217.

Jedrychowski W, Jankowski J, Flak E, Skarupa A, Mroz E, Sochacka–Tatara E et al. Effects of prenatal exposure to mercury on cognitive and psychomotor function in one-year-old infants: epidemiologic cohort study in Poland. Ann Epidemiol 2006; 16: 439–447.

CDC Guideline for the Identification and Management of Lead Exposure in Pregnant and Lactating Women, 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/publications/LeadandPregnancy2010.pdf (accessed December 2013).

US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Toxicological profile for selenium, 2003, pp 1–418.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Toxicological profile for lead, 2007, pp 1–528.

Mahaffey KR, Clickner RP, Bodurow CC . Blood organic mercury and dietary mercury intake: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 and 2000. Environ Health Perspect 2004; 112: 562–570.

McKelvey W, Gwynn RC, Jeffery N, Kass D, Thorpe LE, Garg RK et al. A biomonitoring study of lead, cadmium, and mercury in the blood of New York city adults. Environ Health Perspect 2007; 115: 1435–1441.

Xue F, Holzman C, Rahbar MH, Trosko K, Fischer L . Maternal fish consumption, mercury levels, and risk of preterm delivery. Environ Health Perspect 2007; 115: 42.

Lagerkvist BJ, Soderberg H-A, Nordberg GF, Ekesrydh S, Englyst V . Biological monitoring of arsenic, lead and cadmium in occupationally and environmentally exposed pregnant women. Scand J Work Environ Health 1993; 19 (Suppl 1): 50–53.

Rudge CV, Rollin HB, Nogueira CM, Thomassen Y, Rudge MC, Odland JO . The placenta as a barrier for toxic and essential elements in paired maternal and cord blood samples of South African delivering women. J Environ Monit 2009; 11: 1322–1330.

Gundacker C, Hengstschläger M . The role of the placenta in fetal exposure to heavy metals. Wiener Med Wochenschr 2012; 162: 201–206.

Lagerkvist BJ, Sandberg S, Frech W, Jin T, Nordberg GF . Is placenta a good indicator of cadmium and lead exposure? Arch Environ Health 1996; 51: 389–394.

Kajiwara Y, Yasutake A, Adachi T, Hirayama K . Methylmercury transport across the placenta via neutral amino acid carrier. Arch Toxicol 1996; 70: 310–314.

Sakamoto M, Murata K, Kubota M, Nakai K, Satoh H . Mercury and heavy metal profiles of maternal and umbilical cord RBCs in Japanese population. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 73: 1–6.

Stern AH, Smith AE . An assessment of the cord blood:maternal blood methylmercury ratio: implications for risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect 2003; 111: 1465–1470.

Tsuchiya H, Mitani K, Kodama K, Nakata T . Placental transfer of heavy metals in normal pregnant Japanese women. Arch Environ Health 1984; 39: 11–17.

US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) Mercury. Human exposure, 2009. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/mercury/exposure.htm (accessed December 2013).

Freire C, Ramos R, Lopez-Espinosa M-J, Díez S, Vioque J, Ballester F et al. Hair mercury levels, fish consumption, and cognitive development in preschool children from Granada, Spain. Environ Res 2010; 110: 96–104.

Sundberg J, Jonsson S, Karlsson MO, Hallen IP, Oskarsson A . Kinetics of methylmercury and inorganic mercury in lactating and nonlactating mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1998; 151: 319–329.

Feng WY, Wang M, Li B, Liu J, Chai ZF, Zhao JJ et al. Mercury and trace element distribution in organic tissues and regional brain of fetal rat after in utero and weaning exposure to low dose of inorganic mercury. Toxicol Lett 2004; 152: 223–234.

Yoshida M, Satoh M, Shimada A, Yamamoto E, Yasutake A, Tohyama C . Maternal-to-fetus transfer of mercury in metallothionein-null pregnant mice after exposure to mercury vapor. Toxicology 2002; 175: 215–222.

Kershaw TG, Clarkson TW, Dhahir PH . The relationship between blood levels and dose of methylmercury in man. Arch Environ Health 1980; 35: 28–36.

Barbosa F, Tanus-Santos JE, Gerlach RF, Parsons PJ . A critical review of biomarkers used for monitoring human exposure to lead: advantages, limitations, and future needs. Environ Health Perspect 2005; 113: 1669–1674.

Ronchetti R, van den Hazel P, Schoeters G, Hanke W, Rennezova Z, Barreto M et al. Lead neurotoxicity in children: is prenatal exposure more important than postnatal exposure? Acta Paediatr Suppl 2006; 95: 45–49.

Gulson BL, Mizon KJ, Palmer JM, Patison N, Law AJ, Korsch MJ et al. Longitudinal study of daily intake and excretion of lead in newly born infants. Environ Res 2001; 85: 232–245.

Hu H, Rabinowitz M, Smith D . Bone lead as a biological marker in epidemiologic studies of chronic toxicity: conceptual paradigms. Environ Health Perspect 1998; 106: 1–8.

Leggett RW . An age-specific kinetic model of lead metabolism in humans. Environ Health Perspect 1993; 101: 598.

Bellinger DC, Stiles KM, Needleman HL . Low-level lead exposure, intelligence and academic achievement: a long-term follow-up study. Pediatrics 1992; 90: 855–861.

Canfield RL, Henderson CR, Jr., Cory-Slechta DA, Cox C, Jusko TA, Lanphear BP . Intellectual impairment in children with blood lead concentrations below 10 microg per deciliter. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1517–1526.

Gilbert SG, Weiss B . A rationale for lowering the blood lead action level from 10 to 2 mu g/dL. Neurotoxicology 2006; 27: 693–701.

Hu H, Tellez-Rojo MM, Bellinger D, Smith D, Ettinger AS, Lamadrid-Figueroa H et al. Fetal lead exposure at each stage of pregnancy as a predictor of infant mental development. Environ Health Perspect 2006; 114: 1730–1735.

Grandjean P, Satoh H, Murata K, Eto K . Adverse effects of methylmercury: environmental health research implications. Environ Health Perspect 2010; 118: 1137.

Behrman RE, Butler AS . Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. National Academies Press: Washington DC. 2007 p 381.

Baker JR, Satarug S, Edwards RJ, Moore MR, Williams DJ, Reilly PE . Potential for early involvement of CYP isoforms in aspects of human cadmium toxicity. Toxicol Lett 2003; 137: 85–93.

USEPA (US Environmental Protection Agency). Risk Characterization, Science Policy Council Handbook, . EPA/100/B-00/002. United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Science Policy, Office of Research and Development: Washington, DC. 2000 Available at: http://www.epa.gov/OSA/spc/pdfs/rchandbk.pdf (accessed April 26 2010).

Hales CN, Barker DJ, Clark PM, Cox LJ, Fall C, Osmond C et al. Fetal and infant growth and impaired glucose tolerance at age 64. BMJ 1991; 303: 1019–1022.

Hales CN, Barker DJ . Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus: the thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Diabetologia 1992; 35: 595–601.

Barker DJ . Fetal growth and adult disease. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1992; 99: 275–276.

Barker DJ . The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ 1990; 301: 1111.

Barker DJ . The long-term outcome of retarded fetal growth. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1997; 40: 853–863.

Barker DJ . In utero programming of chronic disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 1998; 95: 115–128.

Barker DJ, Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Osmond C . Fetal origins of adult disease: strength of effects and biological basis. Int J Epidemiol 2002; 31: 1235–1239.

Barker DJ, Osmond C, Golding J, Kuh D, Wadsworth ME . Growth in utero, blood pressure in childhood and adult life, and mortality from cardiovascular disease. BMJ 1989; 298: 564–567.

Barker DJ, Winter PD, Osmond C, Margetts B, Simmonds SJ . Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet 1989; 2: 577–580.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the study participants, and the Boston Medical Center Labor and Delivery Nursing Staff for their support and help with the study. We thank Lingling Fu, MS, for data management, and Ann Ramsey for administrative support. We are also grateful for the dedication and hard work of the field team at the Department of Pediatrics, Boston University School of Medicine. The Boston Birth Cohort (the parent study) is supported in part by the March of Dimes PERI grants (20-FY02-56, 21-FY07-605), the Food Allergy Initiative, the Department of Defense (W81XWH-10-1-0123), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (R21 ES011666, R01 HD041702, R21HD066471, R21AI088609, U01AI090727).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Myers, R., Wei, T. et al. Placental transfer and concentrations of cadmium, mercury, lead, and selenium in mothers, newborns, and young children. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 24, 537–544 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2014.26

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2014.26

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Estimation of health risks associated with dietary cadmium exposure

Archives of Toxicology (2023)

-

Prenatal exposure to heavy metal mixtures and anthropometric birth outcomes: a cross-sectional study

Environmental Health (2022)

-

Neonatal heavy metals levels are associated with the severity of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome: a case–control study

BMC Pediatrics (2022)

-

In-utero co-exposure to toxic metals and micronutrients on childhood risk of overweight or obesity: new insight on micronutrients counteracting toxic metals

International Journal of Obesity (2022)

-

Association between maternal urinary selenium during pregnancy and newborn telomere length: results from a birth cohort study

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2022)