Abstract

Evolutionary adaptations for the exploitation of nutritionally challenging or toxic host plants represent a major force driving the diversification of phytophagous insects. Although symbiotic bacteria are known to have essential nutritional roles for insects, examples of radiations into novel ecological niches following the acquisition of specific symbionts remain scarce. Here we characterized the microbiota across bugs of the family Pyrrhocoridae and investigated whether the acquisition of vitamin-supplementing symbionts enabled the hosts to diversify into the nutritionally imbalanced and chemically well-defended seeds of Malvales plants as a food source. Our results indicate that vitamin-provisioning Actinobacteria (Coriobacterium and Gordonibacter), as well as Firmicutes (Clostridium) and Proteobacteria (Klebsiella) are widespread across Pyrrhocoridae, but absent from the sister family Largidae and other outgroup taxa. Despite the consistent association with a specific microbiota, the Pyrrhocoridae phylogeny is neither congruent with a dendrogram based on the hosts’ microbial community profiles nor phylogenies of individual symbiont strains, indicating frequent horizontal exchange of symbiotic partners. Phylogenetic dating analyses based on the fossil record reveal an origin of the Pyrrhocoridae core microbiota in the late Cretaceous (81.2–86.5 million years ago), following the transition from crypt-associated beta-proteobacterial symbionts to an anaerobic community localized in the M3 region of the midgut. The change in symbiotic syndromes (that is, symbiont identity and localization) and the acquisition of the pyrrhocorid core microbiota followed the evolution of their preferred host plants (Malvales), suggesting that the symbionts facilitated their hosts’ adaptation to this imbalanced nutritional resource and enabled the subsequent diversification in a competition-poor ecological niche.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The evolutionary success of herbivorous insects and their diversification into a wide range of ecological niches is closely connected to the diversification of their host plants (Ehrlich and Raven, 1964). Herbivores and plants engage in an evolutionary arms race, with plants continuously evolving novel chemical defenses or imbalanced nutritional composition to reduce herbivore attacks, and insects adapting by developing strategies to overcome defenses and nutritional challenges. Thus, the diversification of terrestrial plants opened up a multitude of ecological niches, permitting the adaptive radiation of herbivorous insects (Farrell and Mitter, 1994). This is probably best exemplified by the coevolution between butterflies and their host plants, with the diversification of several lepidopteran lineages following their adaptation to a particular group of chemically well-defended plants (Ehrlich and Raven, 1964), for example, Pieridae butterflies on their Brassicales host plants (Wheat et al., 2007).

However, host plant selection and exploitation as a nutritional resource are not only determined by the metabolic capabilities of the insects themselves, but also their associated microbiota (Douglas, 2009; Hosokawa et al., 2007). Microbial symbionts can confer important ecological traits to their hosts, including contributions to digestion (Breznak and Brune, 1994; Warnecke et al., 2007; Lundgren and Lehman, 2010), detoxification (Dowd 1989; Genta et al., 2006) and nutrient provisioning (Borkott and Insam, 1990; van Borm et al., 2002). Consequently, such symbiotic interactions can have a crucial role in the evolutionary diversification of herbivorous insects by facilitating expansion into novel ecological niches (Moran, 2007; Janson et al., 2008). Accordingly, expansion of the host plant range and/or an increased diversification have been observed in gall midges after the acquisition of fungal symbionts (Joy, 2013). Furthermore, the replacement of an ancestral beta-proteobacterial symbiont in sharpshooters (Cicadellidae) with Baumannia—a symbiont with a comparatively large genome (686 kb) encoding for pathways to produce vitamins and cofactors in addition to amino acids—likely facilitated the shift from phloem sap as the main nutrient source to the even more nutritionally imbalanced xylem sap (Takiya et al., 2006). However, despite the wealth of information that is available on the benefits microbes can provide to their insect hosts, the role of symbionts in driving the diversification of insects and their expansion into novel ecological niches remains poorly understood (Janson et al., 2008).

Within the megadiverse insect order Hemiptera, the infraorder Pentatomomorpha contains over 12 500 species (Schaefer, 1993; Schuh and Slater, 1995; Henry, 1997), many of which harbor beneficial symbionts that contribute significantly to host fitness (Muller, 1956; Huber-Schneider, 1957; Schorr, 1957; Abe et al., 1995; Fukatsu and Hosokawa, 2002; Kikuchi et al., 2009; Tada et al., 2011; Salem et al., 2013). Interestingly, symbiotic syndromes (that is, identity and localization of the symbionts) vary greatly among Pentatomomorpha, indicating frequent transitions during the evolutionary history of this group. The most common symbiont-bearing organs across the superfamilies Lygaeoidea, Coreoidea and Pentatomoidea are specialized sacs or tubular outgrowths, called crypts or gastric ceca, in the posterior region of the midgut that harbor beneficial symbionts belonging to the gamma- or beta-proteobacteria (Glasgow, 1914; Miyamoto, 1961; Buchner, 1965; Fukatsu and Hosokawa, 2002; Prado and Almeida, 2009; Hosokawa et al., 2010; Kikuchi et al., 2011a, 2011b). However, several other symbiotic syndromes occur across Pentatomomorpha, including paired or unpaired bacteriomes with intracellular symbionts in some Lygaeoidea (Kuechler et al., 2012; Matsuura et al., 2012), as well as more complex microbial communities in midgut regions devoid of crypts (in Pyrrhocoroidea; Sudakaran et al., 2012). Thus, evolutionary transitions in symbiotic syndromes must have occurred repeatedly in Pentatomomorpha. Although such transitions are expected to have major implications for the functionality of the symbioses, the evolutionary consequences of changes in pentatomomorphan symbiotic syndromes remain enigmatic.

Among pentatomomorphan bugs, the Pyrrhocoridae appear to be exceptional with regard to both the localization of the symbionts and the microbiota composition. Previous studies on Pyrrhocoris apterus and Dysdercus fasciatus revealed that they harbor a distinct and stable microbiota consisting of obligate and facultative anaerobes including Actinobacteria (Coriobacterium glomerans and Gordonibacter sp.), Firmicutes (Clostridium sp.) and Gamma-Proteobacteria (Klebsiella sp.). These bacteria are localized in the ventricose region (M3) of the midgut (Haas and König, 1987; Sudakaran et al., 2012; Salem et al., 2013), which is the main region for the digestion of the ingested food particles (Silva and Terra, 1994; Kodrík et al., 2012). Concordantly, the midgut crypts of Pyrrhocoris apterus and Dysdercus fasciatus are reduced in size and do not contain any symbiotic microbes (Glasgow, 1914; Sudakaran et al., 2012). Similar crypt morphologies have been reported for other genera such as Antilochus and Probergrothius, suggesting that the M3-associated microbial community may be widespread among Pyrrhocoridae (Glasgow, 1914; Rastogi, 1964; Bentz and Kallenborn, 1995; Singh and Singh, 2001; Goel and Chatterjee, 2003). In Pyrrhocoris apterus and Dysdercus fasciatus, the gut microbiota was found to be vital for growth and survival of the host (Salem et al., 2013), through the supplementation of B vitamins by the dual actinobacterial symbionts C. glomerans and Gordonibacter sp. (Salem et al., 2014). As the predominant food source of Pyrrhocoridae, that is, seeds of the plant order Malvales (Kristenová et al., 2011), is deficient in B vitamins, this symbiont-mediated nutritional upgrading plays an important role by allowing the hosts to exploit a nutritionally inadequate diet (Salem et al., 2013).

In this study, we aimed at elucidating the ecological and evolutionary implications of a major transition in symbiotic syndromes. Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that the evolutionary transition to a characteristic midgut core microbiota enabled the diversification of pyrrhocorid bugs on the nutritionally imbalanced diet of Malvales seeds. To this end, we characterized the microbiota across 25 species of Pyrrhocoroidea (22 Pyrrhocoridae and three Largidae species) through a combination of 454 pyrosequencing and quantitative PCR. In addition, we reconstructed a dated phylogeny of the hosts through calibration with the fossil record and compared it with a distance dendrogram of microbial community profiles, as well as strain-level phylogenies of the two vitamin-provisioning actinobacterial symbionts. The results allow us to assess the distribution of the characteristic M3 midgut microbiota across bugs of the superfamily Pyrrhocoridea and to identify the evolutionary origin of this symbiotic syndrome. Subsequently, a comparison with the age of Malvales plants allowed us to test the hypothesis that the acquisition of a specific microbiota preceded the bugs’ diversification on this nutrient-deficient food source. Furthermore, host–symbiont co-cladogenetic analyses shed light on the evolutionary stability and maintenance of the characteristic core microbiota in Pyrrhocoridae. Taken together, the results provide novel insights into the evolutionary transitions and ecological relevance of symbiotic microbial communities in the diverse insect order Hemiptera.

Materials and methods

Insect sample collection and DNA extraction

For characterizing the microbial community and reconstructing symbiont and host phylogenies across the Pyrrhocoroidea superfamily and outgroup taxa, live adult specimens of Pyrrhocoridae (22), Largidae (3), Lygaeidae (2), Oxycarenidae (1) and Rhopalidae (1) were collected from their respective habitats across four different continents (Supplementary Table S1). Bugs were killed and preserved in 70% ethanol until further analysis, and at least one individual per species was kept in ethanol as a voucher specimen. Before DNA extraction, samples were surface sterilized by rinsing with sterile Millipore water, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and then again sterile Millipore water (Billerica, MA, USA). Up to six complete specimens per bug species (or fewer, if less than seven individual specimens were available), were homogenized under liquid nitrogen with sterile pestles. For the Japanese bug specimens, however, only the already dissected midgut was available and used instead of whole individuals. DNA was extracted using the MasterPure DNA Purification Kit (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. An additional lysozyme incubation step (30 min at 37 °C; 4 μl of 100 mg ml–1 lysozyme, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was included before proteinase K digestion to break up Gram-positive bacterial cells (see Sudakaran et al., 2012). Individual extracts were used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis, as well as for PCR and sequencing of host and symbiont genes for phylogenetic analysis. Pooled DNA extracts from each species were used for 454 pyrosequencing of the associated bacterial communities.

Reconstruction of the host phylogeny

The phylogenetic relationships among the Pyrrhocoridae, its sister family Largidae and outgroup taxa were reconstructed using PCR amplification and sequencing of two mitochondrial (cytochrome oxidase I and II) and one nuclear gene (18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA)) for all host species using primers listed in Table 1. PCR was performed in a total reaction volume of 12.5 μl, containing 1 μl of template DNA, 1 × PCR buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 16 mM (NH4)2SO4 and 0.01% Tween 20), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 240 μM dNTPs, 0.8 μM of each primer and 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (VWR International GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). Cycle parameters were as follows: 3 min at 94 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 40 s, 55 °C for 40 s and 72 °C for 40 s, and a final extension step of 4 min at 72 °C. PCR products were then sequenced bidirectionally on an ABI 3730xl capillary DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Protein-coding sequences (COI and COII) were curated and then aligned based on their amino-acid translation in Geneious Pro 5.4 (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand), whereas partial 18S rRNA sequences were aligned using the SINA aligner (Pruesse et al., 2012). The individual alignments were concatenated and used for phylogenetic reconstruction with maximum likelihood algorithms (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI), respectively. An ML tree was computed with FastTree 2.1 using the GTR model, and local support values were estimated with the Shimodaira–Hasegawa test based on 1000 resamplings without reoptimizing the branch lengths for the resampled alignments (Price et al., 2010). For BI (computed using MrBayes 3.1.2; Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001), the data set was partitioned into the three genes, with six substitution types for the CO genes (GTR model), and one for the ribosomal gene (F81 model). Owing to saturation in substitutions, third codon positions were excluded from the analysis for the two mitochondrial genes (COI and COII). The analysis was performed with four chains and a temperature of 0.2 for 10 000 000 generations, and we confirmed that the standard deviation of split frequencies was consistently below 0.01. Trees were sampled every 1000 generations, and a ‘burn-in’ of 1000 was used (=10%). We computed a 50% majority rule consensus tree with posterior probabilities for every node.

Dating of the host phylogeny

Divergence time estimations for the Pyrrhocoroidea superfamily were inferred using BEAST v1.8.0 (Drummond and Rambaut, 2007), by testing various substitution models and parameter settings (see Supplementary Table S2 and S3) on a fixed input tree (the BI tree, see above). Two fossil calibration points were used: (i) two Dysdercus fossils from Florissant beds in Colorado (37.0–33.1 million years ago (mya)) (Scudder, 1890), and (ii) a Pyrrhocoris tibialis fossil from Rott-am-Siebengebirge in Germany (28.5–23.8 mya) (Statz and Wagner, 1950). A hard upper boundary for the age of the root was set to 160 mya, based on to the age of the oldest Pentatomomorpha fossil, as well as the estimated age of the Pentatomomorpha infraorder (~152.9 mya, Upper Jurassic) (Li et al., 2012; Misof et al., 2014). Evaluation and comparison of model parameters were performed using Tracer v1.5 (Drummond and Rambaut, 2007). The maximum clade credibility (consensus) tree was inferred with TreeAnnotator using a burn-in of 5,000 and a posterior probability limit of 0.5 (Drummond and Rambaut, 2007). The consensus tree was visualized with FigTree v1.3.1 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/), including highest posterior density (HPD) intervals.

Characterization of microbial community profiles

Bacterial tag-encoded FLX amplicon pyroseqencing (bTEFAP) was performed to characterize the microbial community composition of members belonging to Pyrrhocoridae, Largidae and outgroup taxa. DNA was sent to external service providers (Research & Testing Laboratories, Lubbock, TX, USA, or MR DNA Lab, Shallowater, TX, USA), and amplification was achieved using the 16S rRNA primers Gray28F and Gray519R (Table 1) (Ishak et al., 2011, Sun et al., 2011). Sequencing libraries were generated through one-step PCR with 30 cycles, using a mixture of Hot Start and HotStar high-fidelity Taq polymerases (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Sequencing extended from Gray28F, using a Roche 454 FLX instrument (Branford, CT, USA) with Titanium reagents and procedures. All low-quality reads (quality cut-off =25) and sequences <200 bp were removed following sequencing, which left between 1990 and 30361 sequences per sample for subsequent analysis.

Processing of the high-quality reads was performed using QIIME (Caporaso et al., 2010b). Sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using multiple OTU picking in combination with chimera checking using usearch (Edgar, 2010) followed by cdhit (Fu et al., 2012) with 97% similarity cut-offs. For each OTU, one representative sequence was extracted (the most abundant) and aligned to the Greengenes core set (available from http://greengenes.lbl.gov/) using PyNast (Caporaso et al., 2010a), with the minimum sequence identity set to 75%. Taxonomy was assigned using the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) classifier (Wang et al., 2007), with a minimum confidence to record an assignment set to 0.80. An OTU table was generated describing the abundance of bacterial phylotypes within each sample (Supplementary Table S4). The table was then manually curated by removing low-abundance OTUs (<0.1% in each of the samples) and through BLASTn of the representative sequences (see Supplementary Data S1) against the NCBI and RDP databases. To visualize the results, OTUs with the same genus-level assignments were combined based on the BLASTn results. The genus-level table was used to construct heatmaps using the R package ‘gplots (heatmap.2)’. For beta-diversity analysis and UPGMA clustering, the raw OTU table was subsampled to the depth of 1500 sequences per sample, and distance matrices were calculated using Bray–Curtis and Jaccard metrics. For visualization, two-dimensional principal coordinate analysis plots and dendrograms based on UPGMA clustering were constructed based on the beta diversity distance matrices.

Quantification of core microbes

qPCRs were performed for the four dominant bacterial symbionts in Pyrrhocoridae (Coriobacterium glomerans, Gordonibacter sp., Clostridium sp. and Klebsiella sp.), using specific 16S rRNA primers (Table 1) on a RotorgeneQ cycler (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in final reaction volumes of 25 μl, containing 1 μl of template DNA (usually a 1:10 dilution of the original DNA extract), 2.5 μl of each primer (10 μm) and 12.5 μl of SYBR Green Mix (Rotor-Gene SYBR Green kit, Qiagen). Standard curves were established using 10−8–10−2 ng of specific PCR product as templates for the qPCR. A NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Peqlab Biotechnology Limited, Erlangen, Germany) was used to measure DNA concentrations for the templates of the standard curve. PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 20 s and 95 °C for 15 s; then a melting curve analysis was performed by increasing the temperature from 60 °C to 95 °C within 20 min. The efficiencies of all four quantitative PCR assays were confirmed to be >99%. Based on the standard curves, the 16S copy numbers of the four dominant symbionts could be calculated for each individual bug from the qPCR threshold values (Ct) by the absolute quantification method (Lee et al., 2006, 2008), taking the dilution factor and the absolute volume of DNA extract into account. The absolute 16S copy numbers were log transformed and then used to visualize the quantitative differences of the bacterial symbionts across different host genera using box plots.

Symbiont (Coriobacteriaceae) strain-level phylogenies

In order to reconstruct strain-level phylogenies for the two actinobacterial symbionts Coriobacterium and Gordonibacter, we followed two different strategies, based on (i) the bTEFAP sequencing data alone, and (ii) a combination of bTEFAP sequences and Sanger sequencing of cloned 16S rRNA amplicons. For the first approach, OTUs were picked individually for each host species, using the parameters as described above. This was necessary to conserve differences among symbiont strains that were below 3% sequence divergence, which would be lost in the combined OTU picking strategy used for assessing the general microbial community composition in Pyrrhocoridae. For each OTU, the longest representative sequence was extracted, and sequences affiliated with the family Coriobacteriaceae were extracted after RDP and BLAST classification (see Supplementary Data S2). The resulting representative sequences were aligned to reference sequences of all Coriobacteriaceae type strains obtained from the RDP (Cole et al., 2014) using the SINA aligner (Pruesse et al., 2012), and phylogenetic relationships were computed using ML as described for the reconstruction of the host phylogeny.

For the second approach, the bTEFAP data were complemented by a cloning/sequencing approach in order to obtain longer and hence more informative reads for phylogenetic analysis. For this purpose, PCR amplifications of the 3′-region of the 16S rRNA of both Coriobacteriaceae symbionts (that is, Coriobacterium glomerans and Gordonibacter sp.) were carried out with the primers Cor-2F and rP2 using a Biometra thermocycler (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany) in total reaction volumes of 12.5 μl containing 1 μl of template DNA, 1 × PCR buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 16 mM (NH4)2SO4 and 0.01% Tween 20), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 240 μM dNTPs, 0.8 μM of each primer and 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (VWR International GmbH). Cycle parameters were as follows: 3 min at 94 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 40 s, 68 °C for 40 s and 72 °C for 40 s, and a final extension step of 4 min at 72 °C. PCR products were cloned into Escherichia coli using the StrataClone PCR Cloning Kit (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transformed E. coli cells were grown on LB agar containing 10 mg ml–1 ampicillin and 2% 5-bromo-4-chloro-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal) (Sigma-Aldrich) for blue/white screening. Colony PCR was performed on eight randomly selected transformants for each insect host with vector primers M13F and M13R (Table 1) using the above-mentioned reaction mix and cycling conditions, except that an annealing temperature of 55 °C was used. PCR products were checked for the expected size on a 1.5% agarose gel (130 V, 30 min) and purified using the peqGOLD MicroSpin Cycle Pure Kit (Peqlab Biotechnologies GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) before sequencing with M13 primers. Nearly full-length Coriobacterium glomerans and Gordonibacter sp. 16S rRNA sequences from different Pyrrhocoridae were obtained by combining the short sequences from OTUs picked for each individual species with bTEFAP and the sequences obtained by PCR/cloning for the respective OTUs. In cases with multiple Coriobacterium (for Scanthius aegypticus, Scanthius obscurus, Pyrrhocoris apterus, Pyrrhocoris sibiricus and Dysdercus fasciatus) or Gordonibacter OTUs (for Scanthius aegypticus and Dysdercus fasciatus) per host species, the most abundant OTU was chosen, and the identity of bTEFAP and cloned sequences was confirmed in the overlapping region to reduce the risk of chimera formation. Sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree reconstruction using ML and BI were done as described above.

Cophylogenetic analysis of host and symbiont

To test for codiversification between hosts and their Coriobacteriaceae symbionts, the phylogenies of the two Coriobacteriaceae symbionts (based on the bTEFAP data alone or the combination with cloning/sequencing data) were compared with the host phylogeny using Treemap 3 (Page RDM, 1995) and Parafit (Legendre et al., 2002). In Treemap, the positions of taxa were randomized on the host and symbiont trees (1000 replicates), and the number of observed codiversification events was compared with the resulting distribution of codiversification events in the randomized data set. For Parafit analysis, a host distance matrix was computed using the R package ‘Ape (cophenetic.phylo)’ based on the phylogenetic tree, and symbiont distance matrices were computed in BioEdit 7.0.5.3 (Hall, 1999) based on the concatenated alignments. Permutation tests (1000 replicates) were run as implemented in ParaFit (Legendre et al., 2002). In order to assess the possible obscuring effect of interspecific predation on co-phylogenetic patterns, we repeated the analyses after omission of known carnivorous host taxa (Antilochus spp., Dindymus lanius) that may have acquired the Coriobacteriaceae symbionts horizontally via feeding on heterospeficic pyrrhocorid bugs.

Results

Host phylogeny and divergence time estimates

To elucidate the evolutionary origin of the Pyrrhocoridae–microbiota association, the phylogenetic relationships across bugs of the Pyrrhocoroidea superfamily were reconstructed. The combination of partial 18S rRNA, COI and COII gene sequences resolved most of the taxonomic relationships within the Pyrrhocoroidea (Figure 1b and Supplementary Figure S1), and divergence time estimations based on two fossil calibration points and a hard lower boundary for the root age yielded consistent age estimates for selected nodes of interest across a range of different substitution models (GTR+I+G, HKY+G, HKY+I+G, TN93+G, TN93+I+G) and parameter settings (Supplementary Table S2 and S3). Omitting the Pyrrhocoris tibialis fossil calibration point did not affect age estimates, whereas omitting either the Dysdercus fossil calibration or the root boundary resulted in significantly increased age estimates (Supplementary Table S3). Based on the tracer analysis of effective sample sizes and marginal likelihood values, the TN93+I+G model with two codon partitions for the protein-coding genes (1+2, and 3), estimated base frequencies, and a relaxed uncorrelated lognormal clock model yielded the most robust results.

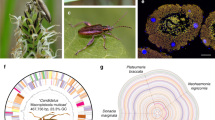

Dated host phylogeny and microbiota profile of 22 species within the family Pyrrhocoridae as well as outgroups (Largidae, Lygaeidae, Oxycarenidae and Rhopalidae). (a) Photographs of selected Pyrrhocoridae host species: adult and fifth instar nymph of Pyrrhocoris apterus, adult Dysdercus cingulatus, adult and nymphs of Dysdercus fasciatus, and a mating pair of Probergrothius sanguinolens (from left to right). (b) Phylogenetic relationships of the hosts (Pyrrhocoridae n=22, Largidae n=3, Lygaeidae n=2, Oxycarenidae n=1, Rhopalidae n=1 species), reconstructed using partial 18S rRNA, cytochrome oxidase I and cytochrome oxidase II gene sequences. Divergence time estimates were derived using BEAST analyses (TN93+I+G model). Selected node ages are shown in mya with 95% HPD interval bars. Dashed branches represent pyrrhocorid taxa without the characteristic core microbiota. The green colored bar indicates the estimated origin of the host plant order Malvales (72–96 mya) (Wang et al., 2009). (c) 2D Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) showing the clustering of host species based on their microbial community profiles using Bray–Curtis (left) and Jaccard (right) distance matrices, respectively. Colors for individual samples correspond to the coloring of taxa in b. (d) Relative abundance of microbial taxa as obtained from 454 pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA amplicons (305,179 reads in total), represented as a heatmap based on log-transformed values. OTUs were combined on the genus level for better visualization, and only genera that amount to >1% of the microbial community in at least one of the host species are displayed. The dendrogram above the heatmap represents the clustering of microbial taxa according to their distribution and abundance across host species. Note the distinct clustering of the four core microbial taxa associated with Pyrrhocoridae.

The phylogenetic analyses revealed an estimated age of 135.7 mya for the superfamily Pyrrhocoroidea (95% HPD interval: 104.4–159.9 mya, Figure 1b). The families Pyrrhocoridae and Largidae formed monophyletic sister taxa that split about 125.4 mya (95% HPD interval: 92.9–154.6 mya; Figure 1b). Within the Pyrrhocoridae family, the genus Probergrothius diverged from the common ancestor of all other taxa about 86.5 mya (95% HPD interval: 63.1–109.3 mya). Around 81.2 mya (95% HPD interval: 58.4–102.2 mya), the clade Dindymus+Antilochus split from the group comprising Dysdercus, Dermatinus, Scanthius, Pyrrhocoris, the unknown pyrrhocorid taxon, and Cenaeus.

Microbial community composition of pyrrhocorid bugs

The microbiota of several species of Pyrrhocoridae (n=22) and Largidae (n=3), as well as outgroup taxa (n=4) were characterized using 454 amplicon pyrosequencing of bacterial 16S rRNA (bTEFAP), which yielded a total of 305 179 sequences. After removing singletons, chimeric sequences and OTUs below 0.1% abundance, the sequences were clustered into 356 OTUs. Bray–Curtis and Jaccard clustering of the host species based on their bacterial community profiles revealed a well-defined cluster containing the genera Dysdercus, Scanthius, Pyrrhocoris, Dindymus, Antilochus and the unknown Pyrrhocoridae species, a second cluster with Probergrothius, Dermatinus and Cenaeus, and separate clusters for members of the Largidae family and the outgroup composed of other Pentatomomorphan bugs (Oxycarenus hyalinipennis, Leptocoris augur, Lygaeus equestris and Spilostethus hospes), respectively (Figure 1c). UPGMA dendrograms of the bacterial communities associated with the host species computed using the beta diversity matrices (Bray–Curtis and Jaccard) yielded qualitatively similar topologies with the major groupings being largely identical (Supplementary Figure S2).

Combining OTUs on the genus level revealed that the microbiota of Pyrrhocoridae bugs was dominated by four core bacterial taxa: Coriobacterium glomerans, Gordonibacter sp. (Actinobacteria), Clostridium sp. (Firmicutes) and Klebsiella sp. (Proteobacteria) (Figure 1d). These taxa were consistently present across Pyrrhocoridae in abundances ranging from 104 to 108 16S rRNA gene copies per individual (Figure 2), with the exception of the genera Probergrothius, Dermatinus and Cenaeus, which lacked the Coriobacteriaceae symbionts (Figures 1d and 2). Furthermore, although OTUs associated with the genera Clostridium and Klebsiella were present in most species of these three host genera, qPCR assays specific for the Pyrrhocoridae-associated Clostridium and Klebsiella OTUs were negative for all samples except two of the Probergrothius specimens, indicating that the Clostridium and Klebsiella OTUs associated with these three genera differ from those of the other Pyrrhocoridae (Figure 2). Thus, the host genera Probergrothius, Dermatinus and Cenaeus lacked the microbiota that is characteristic for other Pyrrhocoridae, which is also reflected in their separate clustering in the principal coordinate analyses (Figure 1c).

Evolutionary transitions in symbiotic syndromes in Pyrrhocoroidea, and abundance of core microbial taxa. (a) Schematic phylogeny of Pyrrhocoridae and Largidae genera (adapted from Figure 1b). Pyrrhocoridae taxa with core microbiota are given in black, those taxa without the core microbiota are in dark gray, and the Largidae with crypt-associated symbionts are in light gray. Reconstructed evolutionary transitions in symbiotic syndromes are indicated on the phylogeny. Numbers of validly described extant species are given behind each genus name (from Hussey, 1929). (b) Abundance of the four core symbiont taxa (Coriobacterium glomerans, Gordonibacter sp., Clostridium sp. and Klebsiella sp.) across multiple specimens of the nine different genera of Pyrrhocoridae (Dysdercus (n=37), Dermatinus (n=2), Scanthius (n=5), Pyrrhocoris (n=7), u nknown Pyrrhocoridae (n=6), Cenaeus (n=5), Dindymus (n=6), Antilochus (n=7) and Probergrothius (n=23)) and two genera of Largidae (Physopelta (n=4) and Largidae (n=1)). Abundance was assessed as 16S rRNA gene copy numbers using qPCR, based on one to six replicate individuals per host species, which were then combined on the genus level. Lines represent medians, boxes comprise the 25–75 percentiles and whiskers denote the range.

The microbiota of members of the family Largidae (the sister taxon to the Pyrrhocoridae) was dominated by Burkholderia and completely lacked the Pyrrhocoridae-associated core microbes (Figures 1d and 2). Similarly, the core microbiota was absent from other pentatomomorphan outgroup species: the microbiota of both Oxycarenus hyalinipennis (Oxycarenidae) and Leptocoris augur (Rhopalidae) was dominated by Wolbachia sp. and Bartonella sp., whereas the Lygaeidae species Lygaeus equestris and Spilostethus hospes contained consortia of Trabulsiella sp. and Stenotrophomonas sp. (L. equestris), or Wolbachia sp. and Rickettsia sp. (S. hospes), respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis of the Coriobacteriaceae symbionts

The Pyrrhocoridae core microbiota contains two actinobacterial symbionts that were previously shown to be essential for growth and survival in P. apterus and D. fasciatus through the supplementation of B vitamins (Salem et al., 2013, 2014). The phylogeny of both Coriobacteriaceae symbionts was reconstructed based on the set of short read sequences from bTEFAP representing the Coriobacteriaceae symbiont OTUs from each pyrrhocorid species (Figure 3). In addition, we amplified and sequenced the symbionts’ 3’-region of the 16S rRNA gene sequences from 13 different host species, as well as only Coriobacterium glomerans from Dysdercus decussatus, and only Gordonibacter sp. from two Probergrothius species (that is, P. nigricornis and P. sanguinolens). Subsequently these sequences were combined with the bTEFAP representative sequences to enhance the resolution of the phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Figure S3). The phylogenetic analyses revealed that the symbiotic Coriobacterium glomerans and Gordonibacter sp. strains form two distinct monophyletic clades within the family Coriobacteriacae, which is consistent with a single acquisition event for each symbiont and subsequent host–symbiont coevolution (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S3). A possible exception are the Gordonibacter symbionts of the basal pyrrhocorid genus Probergrothius, which group within the monophyletic symbiont cluster in the combined phylogeny (Supplementary Figure S3), yet fall outside when only the bTEFAP sequences are considered (Figure 3). Interestingly, several host species contained two or more dominant OTUs for one or both of the actinobacterial symbionts. Specifically, more than one Coriobacterium OTU was observed for Scanthius aegypticus, Scanthius obscurus, Pyrrhocoris apterus, Pyrrhocoris sibiricus and Dysdercus fasciatus, whereas two or more Gordonibacter OTUs were detected for Scanthius aegypticus and Dysdercus fasciatus. For Pyrrhocoris apterus and Dysdercus fasciatus, the occurrence of two distinct Coriobacterium sequences, respectively, was previously confirmed using cloning and sequencing (Kaltenpoth et al., 2009). Thus, the multiple Coriobacterium and Gordonibacter OTUs observed here for several host species likely reflect true symbiont microdiversity rather than 454 sequencing artifacts. Although at present we cannot exclude the possibility that the multiple Coriobacteriaceae sequences found in individual Pyrrhocoridae species represent divergent 16S rRNA copies within the same symbiont genome, the presence of multiple distinct strains seems much more likely given the high degree of similarity of the two 16S rRNA copies (99.72%) in the sequenced genome of C. glomerans isolated from P. apterus (Stackebrandt et al., 2013).

Cophylogenetic analysis of (a) the dual actinobacterial symbionts (Coriobacterium glomerans and Gordonibacter sp.) and (b) their Pyrrhocoridae hosts. The symbiont phylogeny is based on partial 16S rRNA bTEFAP sequences from OTUs picked for each individual species (see Supplementary Data S2). Colors for individual symbiont strains correspond to the coloring of host taxa in Figure 1b. For each Coriobacteriaceae OTU, the relative abundance (in relation to the respective host’s complete microbial community) is given in brackets behind the strain designation. Host–symbiont associations are shown by connecting lines. Values at the nodes represent local support values from the FastTree analysis (GTR model).

In addition to the occurrence of multiple OTUs within individual host species, the incongruence of the phylogenies of both Coriobacteriaceae symbionts with the Pyrrhocoridae host phylogeny (Coriobacterium glomerans: Parafit: P=0.974, TreeMap: P=0.345; Gordonibacter sp.: Parafit: P=0.978, TreeMap: P=0.449) (Supplementary Figure S3) suggest horizontal exchange of symbionts between host species. Given the symbiont microdiversity observed in the bTEFAP data, we paid special attention to avoid the generation of possible chimeric sequences when combining bTEFAP reads and sequences obtained after cloning of PCR amplicons. Owing to the high similarity of different symbiont strains, however, the possibility of chimera formation for the symbionts of individual host taxa cannot be completely ruled out, which may hinder accurate co-phylogenetic analyses. To exclude the possibility that co-phylogenetic patterns were additionally obscured by interspecific predation among pyrrhocorid bugs resulting in transient Coriobacteriaceae being picked up in the bTEFAP sequences, we repeated the analyses after excluding known predatory taxa (Antilochus spp., Dindymus lanius). Although some symbiont taxa clustered according to their host genera (particularly Pyrrhocoris and Scanthius for Gordonibacter, and Dysdercus for Coriobacterium), the tests for co-cladogenesis remained nonsignificant. Thus, although the Pyrrhocoridae maintain a specific microbiota, horizontal transmission between co-occurring species apparently played an important role during the evolution of this symbiosis. As the Coriobacteriaceae symbionts are localized in the same region of the midgut and can be co-transmitted both vertically and horizontally (Kaltenpoth et al., 2009), we also tested for co-cladogenesis of the two symbiont lineages. Randomization of phylogenetic trees or distance matrices and subsequent statistical evaluation, however, yielded no evidence for co-cladogenesis between Coriobacterium glomerans and Gordonibacter sp. strains across host taxa (Parafit: P=0.898, TreeMap: P=0.251).

Discussion

In this study, we characterized the microbiota associated with bugs of the hemipteran families Pyrrhocoridae and Largidae, and investigated the origin and evolutionary dynamics of the host–microbiota association on both the community and strain level. The results provide insights into an evolutionary transition from individual crypt-associated symbionts to a more complex microbiota that is localized in the insect’s midgut. This transition coincided with the evolution of the hosts’ preferred food plants and preceded the major radiation of pyrrhocorid bugs, highlighting the possible importance of the microbial community in adapting to novel ecological niches.

Nutritional contributions of the core microbiota associated with pyrrhocorid host

Members of the Pyrrhocoridae are predominantly phytophagous, feeding on seeds of the plant order Malvales, with a few notable exceptions such as Probergrothius angolensis, which feeds on seeds of the ancient gymnosperm Welwitschia mirabilis (Wetschnig and Depisch, 1999). Despite being phylogenetically distant, these host plants share similar phytochemical defenses, particularly cylcopropenoic fatty acids (CPFAs) (Allen et al., 1967). These compounds are known to be toxic to insects because of the inhibition of fatty acid desaturation (Allen et al., 1967). Interestingly, the noxious effects of CPFAs are particularly problematic under B vitamin starvation conditions, as artificial supplementation of vitamins partly abolished the adverse effects of CPFAs in rats (Schneider et al., 1968). As the seeds of Malvales plants are known to be deficient in B vitamins (Whitsitt, 1933), the combined effect of vitamin deficiency and CPFAs likely poses severe nutritional challenges to insects attempting to exploit this food source.

In previous studies, we have shown that P. apterus and D. fasciatus, two members of the Pyrrhocoridae family, harbor a stable and specific midgut microbiota that is dominated by four microbial taxa: Actinobacteria (Coriobacterium glomerans, Gordonibacter sp.), Firmicutes (Clostridium sp.) and Proteobacteria (Klebsiella sp.), irrespective of the geographical origin or laboratory diet of the bugs (Sudakaran et al., 2012; Salem et al., 2013). Our present characterization of the microbiota associated with 22 different species belonging to nine genera of Pyrrhocoridae using 16S rRNA amplicon pyrosequencing and quantitative PCR revealed the presence of the same dominant bacterial taxa across six (Dysdercus, Scanthius, Pyrrhocoris, Dindymus, Antilochus and the unidentified specimen) out of the nine investigated genera of Pyrrhocoridae, but absence from the other three genera as well as all of the non-Pyrrhocoridae outgroup taxa, including the sister family Largidae (Figures 1 and 2).

The presence of a consistent core microbiota across most Pyrrhocoridae suggests that the symbionts are likely vital to the hosts’ fitness. Concordantly, experimental removal of the actinobacterial symbionts by egg surface sterilization had a strong negative effect on the fitness of the host as indicated by severely reduced survival during development and strongly impaired fecundity of adult individuals (Salem et al., 2013). Furthermore, a recent study that combined fitness assays of Actinobacteria-deprived and control bugs on an artificial diet with transcriptome sequencing of the host, and genomic analysis of one of the Coriobacteriaceae symbionts (C. glomerans) revealed that these symbionts supplement the nutrition of the host with limiting B vitamins (Salem et al., 2014), which may also mitigate the toxic effects of the plants’ CPFAs in the bugs’ gut (Schneider et al., 1968). Thus, the Coriobacteriaceae symbionts are tightly integrated into the hosts’ metabolism and play an important role for nutrient provisioning and, possibly, detoxification (Salem et al., 2014). The third core microbial taxon, Clostridium sp., is affiliated with the Lachnospiraceae (Firmicutes), whose members are anaerobic fermenters. Their production of butyric acid can serve as a nutrient source to the host (Meehan and Beiko, 2014) and/or reduce the abundance of bacterial pathogens in the insect gut by stimulating mucin and antimicrobial peptide production (Hamer et al., 2008). Given that many Clostridium species have cellulolytic capabilities (Lynd et al., 2002), the symbiont could also contribute to cellulose digestion. However, as Lachnospiraceae have to our knowledge not yet been functionally described as symbionts of insects other than Pyrrhocoridae, their contribution to host fitness remains speculative. The fourth symbiont, Klebsiella sp., belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae (Gamma-Proteobacteria). Klebsiella are facultative anaerobes that are associated with diverse eukaryotic organisms (Bagley 1985; Podschun and Ullmann, 1998). Some strains are capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen to be utilized by plants (Cakmakci et al., 1981), as well as insects (leaf-cutter ants; Pinto-Tomas et al., 2009), so the Pyrrhocoridae-associated Klebsiella may also be involved in the nitrogen metabolism of their hosts. Taken together, the symbiont-provided benefits may enable the pyrrhocorid hosts to successfully exploit a nutritionally inadequate food source (the seeds of Malvales plants) that is unpalatable to many other insects, because of the low concentrations of available B vitamins and the presence of toxic CPFAs.

Evolutionary origin of the Pyrrhocoridae–microbiota association

The M3 core microbiota of the Pyrrhocoridae was distinctly different from that of their closest relatives, the Largidae, which harbored more or less a monoculture of Burkholderia (Figure 1d). Related Burkholderia symbionts have been described from the midgut crypts of several other bug taxa in the superfamilies Coreoidea and Lygaeoidea (Kikuchi et al., 2011a, 2011b). As Largidae also possess well-defined midgut crypts (Glasgow, 1914), a crypt localization seems very likely for their Burkholderia symbionts. The absence of Burkholderia or any other dominant symbiont taxon (Figure 1d), as well as the simple structure of the midgut crypts in the basal pyrrhocorid genus Probergrothius (Rastogi, 1964; Goel and Chatterjee, 2003) suggests that the Pyrrhocoridae lost their crypt-associated symbionts soon after the evolutionary split from the Largidae, which occurred around 125.2 mya ago (Figures 1a and 2). The core microbiota consisting of Coriobacterium glomerans, Gordonibacter sp., Clostridium sp. and Klebsiella sp., however, was not established before Probergrothius split off from the rest of the pyrrhocorids in the late Cretaceous (81.2–86.5 mya) (Figures 1 and 2). Thus, the pyrrhocorid symbiosis with its extracellular core microbiota is younger than most of the known intracellular nutritional mutualisms in insects, such as the aphid—Buchnera (80–150 mya; Von Dohlen and Moran 2000), cockroach—Blattabacterium (135–250 mya; Bandi et al., 1995), planthopper—Vidania (>130 mya; Urban and Cryan, 2012) and Auchenorrhyncha—Sulcia symbioses (260–280 mya; Moran et al., 2005). Importantly, however, the estimated age of the Pyrrhocoridae core microbiota coincides with the inferred origin of their host plant order Malvales (72–96 mya, Wang et al., 2009; Figure 1). Although at present, host and symbiont contributions toward exploitation of the diet cannot be completely disentangled, the increased diversity in pyrrhocorid bugs after the acquisition of the M3-localized anaerobic core microbiota suggests an important contribution of the symbionts toward the adaptation of their hosts to Malvales seeds as a nutritional resource and the subsequent diversification of Pyrrhocoridae (Figure 2).

Our results indicate that some pyrrhocorid genera apparently lack the characteristic microbiota. As mentioned above, Probergrothius likely diverged from the rest of the Pyrrhocoridae before the acquisition of the core microbiota. Although this genus shows the occurrence of Clostridium sp., the symbiont differs from the taxonomically related OTUs of the other pyrrhocorids, and the two actinobacterial symbionts are entirely lacking in Probergrothius. Despite the absence of these symbionts, some of the Probergrothius species successfully exploit Malvales seeds, whereas others feed on Welwitschia seeds (Wetschnig and Depisch, 1999; Goel and Chatterjee 2003), which contain CPFAs as well (Aitzetmuller and Vosmann, 1998). Assuming that the switch to Malvales host plants already occurred at the base of the Pyrrhocoridae, it likely coincided with the transition from crypt-associated symbionts to an anaerobic midgut community, whereas the acquisition of the characteristic core microbiota only happened secondarily after the split from Probergrothius. The latter transition likely represented a key adaptation to exploit the Malvales ecological niche, as is reflected in the much greater diversity in the pyrrhocorid clade without Probergrothius (see Figure 2). How bugs in the genus Probergrothius fulfill their dietary requirements of B vitamins and prevent the toxic effects of CPFAs is currently unknown. In this context, however, it is noteworthy that one of the Lygaeidae outgroup taxa, Oxycarenus hyalinipennis, co-exists in the same environment as several other Pyrrhocoridae and also feeds on Malvales seeds (Saxena and Bhatnagar, 1958). Despite sharing the same ecological niche, O. hyalinipennis harbors a completely different microbiota comprising mainly Wolbachia sp. and Bartonella sp., suggesting that different adaptations have evolved independently to cope with the nutritional challenges associated with feeding on Malvales seeds.

In contrast to the primary lack of the core microbiota in Probergrothius spp., Cenaeus carnifex and Dermatinus sp. lost the core microbiota secondarily (Figure 1b). Although the Pyrrhocoridae predominantly feed on Malvales seeds, some species including members of the genera Cenaeus, Pyrrhocoris, Antilochus and Dindymus have been reported to predominantly (Antilochus and Dindymus) or occasionally (Cenaeus and Pyrrhocoris) utilize dead insects or other animals as a food source (Ahmad and Schaefer, 1987, Socha, 1993). A carnivorous supplementation of an otherwise phytophagous diet could provide essential nutrients (including B vitamins) and thereby relax the selective pressures to maintain a nutrient-supplementing microbial community. This scenario could explain the loss of symbionts in Cenaeus. However, no information on the feeding biology of Dermatinus is available. Thus, the scenario in which symbionts were lost following a shift to a partially or completely carnivorous diet remains speculative. In this context, however, it is interesting to note that although the genera Antilochus and Dindymus have been characterized as predominantly carnivorous (Ahmad and Schaefer, 1987; Jackson and Barrion, 2002; Kohno et al., 2004; Ari Noriega and Huay Lee, 2010), they retained the core microbiota in qualitatively and quantitatively similar composition as other Pyrrhocoridae genera (Figures 1 and 2). Although it is possible that the core bacteria in Antilochus and Dindymus represent transient associates acquired via feeding on sympatrically occurring pyrrhocorid bugs, their numerical abundance implies a contribution to host fitness. Thus, the link between the carnivorous supplementation of the predominantly phytophagous diet and the secondary loss of symbionts in some Pyrrhocoridae requires further investigation, which should particularly focus on the functional role the gut-associated microbial communities have in different Pyrrhocoridae genera.

Mixed transmission mode and partner specificity

In insect–microbe interactions, functionally relevant and vertically transmitted microbial symbionts are expected to co-evolve and co-diversify with their host, resulting in the congruence of host and symbiont phylogenies. Such patterns are well-documented in several insects harboring primary intracellular endosymbionts (Moran et al., 2008), as well as in some tightly integrated extracellular symbioses (for review, see Salem et al., 2015). More recently, changes in microbial community profiles have also been suggested to mirror the evolutionary relationships among host taxa in symbiotic associations that remain stable over long evolutionary timescales (Sanders et al., 2014). In this study, the gut microbiota of the Pyrrhocoridae family remains both quantitatively and qualitatively stable across most host species. However, multiple discrepancies between the host phylogeny and the symbiont relationships on the community and strain level (C. glomerans and Gordonibacter sp.), with overall no statistical support for co-cladogenesis, strongly imply horizontal transmission of symbionts between heterospecific hosts (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S3). In addition, multiple co-occurring strains of the two actinobacterial symbionts were detected in several host taxa. It is well documented in Pyrrhocoris apterus that although the symbionts are predominantly transmitted vertically from mother to offspring through egg smearing, symbiont-deprived bugs readily acquire the microbes horizontally from conspecifics through coprophagy in the laboratory (Kaltenpoth et al., 2009). A second possible explanation for the horizontal exchange of symbionts could be the tendency among some Pyrrhocorid bugs to occasionally prey on other co-occurring pyrrhocorid species. Similar findings of a predominantly vertical transmission with a low rate of horizontal transmission (that is, mixed transmission mode) in a range of other insects challenge the traditional view of a strict vertical transmission of most insect mutualists and instead highlight the importance of mixed transmission modes across a wide range of host taxa (Ebert, 2013). Examples for this mixed transmission mode include burying beetles (Kaltenpoth and Steiger 2014), fruit flies (Aharon et al., 2013), beewolves (Kaltenpoth et al., 2014), termites (Schauer et al., 2012) and bumblebees (Koch and Schmid-Hempel, 2011).

Major transitions in symbiotic syndromes in the hemipteran infraorder Pentatomomorpha

Symbiotic associations with bacteria have been extensively studied in the hemipteran infraorder Pentatomomorpha, and the diversity of symbiont taxa, localizations and transmission routes provide interesting insights into evolutionary transitions in symbiotic syndromes. Many Pentatomomorpha possess specialized crypts in the posterior midgut M4 region that harbor primary symbionts (Glasgow, 1914) (Figure 4). Given the occurrence of midgut crypts and associated symbionts across four of the five pentatomomorphan superfamilies, they likely represent the ancestral localization of symbionts in the Pentatomomorpha excluding the fungivorous Aradoidea (Figure 4). In the superfamily Pentatomoidea, most crypt-associated symbionts are vertically transmitted Gamma-Proteobacteria that contribute to the nutrition of their hosts (Abe et al., 1995; Hosokawa et al., 2005; Prado et al., 2006; Kikuchi et al., 2009; Kaiwa et al., 2010, Kaiwa et al., 2014) (Figure 4). By contrast, bugs belonging to the Coreoidea superfamily and several families within the Lygaeoidea harbor Burkholderia symbionts in their midgut crypts. In some cases, such as in the bean bug Riptortus pedestris, every host generation acquires these symbionts de novo from the environment (Kikuchi et al., 2007) (Figure 4). Several other families in the Lygaeoidea have secondarily lost the crypt-inhabiting symbionts, and some evolved bacteriomes that house a distinct clade of Gamma-Proteobacteria (Kuechler et al., 2012; Matsuura et al., 2012; Figure 4).

Symbiotic syndromes (i.e., symbiont identity and localization) in bugs of the infraorder Pentatomomorpha. The superfamily-level phylogenetic relationships of the hosts were obtained from earlier studies based on the 18S rRNA (Xie et al., 2005) and whole mitochondrial genomes (Hua et al., 2008). The gray bar indicates the previously hypothesized evolutionary origin of crypt-associated Burkholderia in stinkbugs (Kikuchi et al., 2011a, 2011b), whereas the black bar denotes the revised suspected origin of this association, based on the discovery of Burkholderia symbionts in Largidae (this study).

Based on the occurrence of crypt-associated Burkholderia symbionts in Coreoidea and Lygaeoidea, previous studies hypothesized that the Burkholderia symbiosis originated in the ancestor of these two sister taxa (Figure 4) (Kikuchi et al., 2011a). However, our findings of highly abundant Burkholderia in all three investigated Largidae species, together with previous reports on complex and well-defined midgut crypts in this family (Glasgow, 1914; Miyamoto, 1961), suggest that the association with Burkholderia is more ancient than previously thought, with a likely origin at the base of the clade comprising the Pyrrhocoroidea, Coreoidea and Lygaeoidea (Figure 4). Under this scenario, Burkholderia symbionts that are localized in midgut crypts also constituted the ancestral state for the Pyrrhocoroidea, with a subsequent loss of crypts and Burkholderia in the Pyrrhocoridae. Interestingly, although seed feeding is widespread among pentatomomorphan bugs, the transition to an anaerobic microbiota in the midgut lumen appears to be confined to the Pyrrhocoridae. As discussed above, the specialized nutritional challenges associated with the switch to the Malvales host plants may have favored this evolutionary transition in symbiotic syndromes.

Evolutionary transitions in symbiotic associations have been described repeatedly across different insect taxa (Bennett and Moran, 2013; Hansen and Moran, 2014; Koga et al., 2013). Evidently, extracellularly localized and transmitted symbionts are more flexible than intracellular associations, because they provide more opportunities to replace less beneficial symbionts (Salem et al., 2015). Nevertheless, even replacements of obligate intracellular symbionts have been described in several Auchenorrhynchan lineages (Bennett and Moran, 2013; Koga et al., 2013; Koga and Moran, 2014), as well as in aphids (Koga et al., 2003) and weevils (Toju et al., 2013). In the Pyrrhocoridae, the symbiotic association transitioned from specialized crypt-associated symbionts to a midgut-localized bacterial community. Several transitions between extracellular symbionts harbored in crypts or in the lumen of the midgut and intracellular symbionts housed in bacteriomes have been observed in related hemipteran families (Kikuchi et al., 2011a, 2011b; Kuechler et al., 2012; Matsuura et al., 2012; Bennett and Moran 2013; Hansen and Moran 2014), but their ecological and evolutionary implications remain poorly understood. Our results suggest that changes in the symbionts’ localization and identity can allow for the insect host to invade a novel ecological niche and subsequently diversify. Future studies on the functional relevance of microbial symbionts during such transitions in symbiotic syndromes may reveal general principles in the ecological factors and evolutionary constraints that underlie niche expansions and lineage diversifications.

Conclusions

This study provides the first comprehensive characterization of the microbiota associated with different species of Pyrrhocoridae and yields novel insights into the evolution of this mutualistic symbiosis. The evolution of the specific core microbiota in Pyrrhocoridae during the late Cretaceous followed the origin of their preferred host plants (Malvales), suggesting that the symbionts were instrumental in allowing the host to adapt to and diversify in this ecological niche. Pyrrhocorid bugs represent one of the few established and experimentally amenable systems that can be used to address fundamental questions on the interactions of multiple bacterial symbionts within the gut of an insect host. The exploration of the symbionts’ functional importance and the molecular basis of host–symbiont interactions may shed new light on the role microbial partners had for the evolutionary success of insects.

Data accessibilty

18S rRNA, COI and COII gene sequences of Pyrrhocoridae, Largidae and outgroup taxa along with near full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences of the Coriobacteriaceae symbionts across several species of Pyrrhocoridae were deposited in the NCBI database, and accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The OTU table and corresponding representative sequences describing the occurrence of bacterial phylotypes across different Pyrrhocoroidea and outgroup taxa are given in Supplementary Table S4 and Supplementary Data S1. The Coriobacteriaceae representative OTU sequences from the bTEFAP analysis of individual pyrrhocorid species used for the phylogenetic analyses are given in Supplementary Data S2. The 454 pyrosequencing data (raw sff files) are available from the NCBI SRA database under the accession number SRP050243.

Accession codes

References

Abe Y, Mishiro K, Takanashi M . (1995). Symbiont of brown-winged green bug. Plautia-Stali Scott. Jpn J Appl Entomol Zool 39: 109–115.

Aharon Y, Pasternak Z, Ben Yosef M, Behar A, Lauzon C, Yuval B et al. (2013). Phylogenetic, metabolic, and taxonomic diversities shape mediterranean fruit fly microbiotas during ontogeny. Appl Environ Microbiol 79: 303–313.

Ahmad I, Schaefer CW . (1987). Food plants and feeding biology of the Pyrrhocoroidea (Hemiptera). Phytophaga 1: 75–92.

Aitzetmuller K, Vosmann K . (1998). Cyclopropenoic fatty acids in gymnosperms: the seed oil of Welwitschia. J Am Oil Chem Soc 75: 1761–1765.

Allen E, Johnson AR, Fogerty AC, Pearson JA, Shenstone FS . (1967). Inhibition by cyclopropene fatty acids of the desaturation of stearic acid in hen liver. Lipids 2: 419–423.

Ari Noriega J, Huay Lee JS . (2010). Predation on onthophagus Rutilans sharp (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) by Dindymus albicornis (Fabricius) (Hemiptera: Pyrrhocoridae). Boletin de la SEA 46: 609–610.

Bagley ST . (1985). Habitat association of Klebsiella species. Infect Control 6: 52–58.

Bandi C, Sironi M, Damiani G, Magrassi L, Nalepa CA, Laudani U et al. (1995). The establishment of intracellular symbiosis in an ancestor of cockroaches and termites. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 259: 293–299.

Bennett GM, Moran NA . (2013). Small, smaller, smallest: the origins and evolution of ancient dual symbioses in a phloem-feeding insect. Genome Biol Evol 5: 1675–1688.

Bentz C, Kallenborn HG . (1995). Fine-structure of the gastric ceca of the cotton stainer Dysdercus-Intermedius (Heteroptera, Pyrrhocoridae). Entomol Gen 20: 27–36.

Borkott H, Insam H . (1990). Symbiosis with bacteria enhances the use of chitin by the springtail, Folsomia-Candida (Collembola). Biol Fertil Soils 9: 126–129.

Boutin-Ganache I, Raposo M, Raymond M, Deschepper CF . (2001). M13-tailed primers improve the readability and usability of microsatellite analyses performed with two different allele-sizing methods. BioTechniques 31: 24–28.

Breznak JA, Brune A . (1994). Role of microorganisms in the digestion of lignocellulose by termites. Annu Rev Entomol 39: 453–487.

Buchner P . (1965) Endosymbiosis of Animals with Plant Microorganisms. Interscience publishers: : New York, USA.

Cakmakci ML, Evans HJ, Seidler RJ . (1981). Characteristics of nitrogen-fixing Klebsiella oxytoca isolated from wheat roots. Plant and Soil 61: 53–63.

Caporaso JG, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Knight R . (2010a). PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics 26: 266–267.

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK et al. (2010b). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7: 335–336.

Cole JR, Wang Q, Fish JA, Chai B, McGarrell DM, Sun Y et al. (2014). Ribosomal Database Project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D633–D642.

Dowd PF . (1989). Insitu production of hydrolytic detoxifying enzymes by symbiotic yeasts in the cigarette beetle (Coleoptera, Anobiidae). J Econ Entomol 82: 396–400.

Douglas AE . (2009). The microbial dimension in insect nutritional ecology. Funct Ecol 23: 38–47.

Drummond AJ, Rambaut A . (2007). BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol 7: 214.

Ebert D . (2013). The epidemiology and evolution of symbionts with mixed-mode transmission. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 44: 623–643.

Edgar RC . (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26: 2460–2461.

Ehrlich PR, Raven PH . (1964). Butterflies and plants - a study in coevolution. Evolution 18: 586–608.

Farrell BD, Mitter C . (1994). Adaptive radiation in insects and plants - time and opportunity. Am Zool 34: 57–69.

Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W . (2012). CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28: 3150–3152.

Fukatsu T, Hosokawa T . (2002). Capsule-transmitted gut symbiotic bacterium of the Japanese common plataspid stinkbug, Megacopta punctatissima. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 389–396.

Genta FA, Dillon RJ, Terra WR, Ferreira C . (2006). Potential role for gut microbiota in cell wall digestion and glucoside detoxification in Tenebrio molitor larvae. J Insect Physiol 52: 593–601.

Glasgow H . (1914). The gastric cæca and the cæcal bacteria of the Heteroptera. Biol Bull 26: 101–170.

Goel AP, Chatterjee VC . (2003). On the digestive tract of Odontopus nigricornis Stal (Heteroptera: Pyrrhocoridae) and survival time during starvation. Uttar Pradesh J Zool 23: 97–99.

Haas F, König H . (1987). Characterisation of an anaerobic symbiont and the associated aerobic bacterial flora of Pyrrhocoris apterus (Heteroptera: Pyrrhocoridae). FEMS Microbiol Lett 45: 99–106.

Hall TA . (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 41: 95–98.

Hamer HM, Jonkers D, Venema K, Vanhoutvin S, Troost FJ, Brummer RJ . (2008). The role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 27: 104–119.

Hansen AK, Moran NA . (2014). The impact of microbial symbionts on host plant utilization by herbivorous insects. Mol Ecol 23: 1473–1496.

Henry TJ . (1997). Phylogenetic analysis of family groups within the infraorder Pentatomomorpha (Hemiptera: Heteroptera), with emphasis on the Lygaeoidea. Ann Entomol Soc Am 90: 275–301.

Hosokawa T, Kikuchi Y, Meng X, Fukatsu T . (2005). The making of symbiont capsule in the plataspid stinkbug Megacopta punctatissima. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 54: 471–477.

Hosokawa T, Kikuchi Y, Shimada M, Fukatsu T . (2007). Obligate symbiont involved in pest status of host insect. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 274: 1979–1984.

Hosokawa T, Kikuchi Y, Nikoh N, Meng XY, Hironaka M, Fukatsu T . (2010). Phylogenetic position and peculiar genetic traits of a midgut bacterial symbiont of the stinkbug Parastrachia japonensis. Appl Environ Microbiol 76: 4130–4135.

Hosokawa T, Kikuchi Y, Nikoh N, Fukatsu T . (2012). Polyphyly of gut symbionts in stinkbugs of the family Cydnidae. Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 4758–4761.

Hua J, Li M, Dong P, Cui Y, Xie Q, Bu W . (2008). Comparative and phylogenomic studies on the mitochondrial genomes of Pentatomomorpha (Insecta: Hemiptera: Heteroptera). BMC Genomics 9: 610.

Huber-Schneider L . (1957). Morphologische und physiologische untersuchungen an der wanze Mesocerus marginatus L. und ihren symbionten (Heteroptera). Zoomorphology 46: 433–480.

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F . (2001). MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17: 754–755.

Hussey RF . (1929) General Catalogue of the Hemiptera—Fascicle III: Pyrrhocoridae. Smith College: Northampton, MA, USA, 144 pp.

Ishak H, Plowes R, Sen R, Kellner K, Meyer E, Estrada D et al. (2011). Bacterial diversity in Solenopsis invicta and Solenopsis geminata ant colonies characterized by 16S amplicon 454 pyrosequencing. Microb Ecol 61: 821–852.

Jackson RR, Barrion AT . (2002). Foraging behavior, distribution and predators of Dindymus pulcher Stal (Hemiptera: Pyrrhocoridae), a snail-eating bug from the Philippines. Philippine Entomologist 16: 53–67.

Janson EM, Stireman JO, Singer MS, Abbot P . (2008). Phytophagous insect-microbe mutualisms and adaptive evolutionary diversification. Evolution 62: 997–1012.

Joy JB . (2013). Symbiosis catalyses niche expansion and diversification. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 280: 7.

Kaiwa N, Hosokawa T, Kikuchi Y, Nikoh N, Meng XY, Kimura N et al. (2010). Primary gut symbiont and secondary, Sodalis-allied symbiont of the scutellerid stinkbug Cantao ocellatus. Appl Environ Microbiol 76: 3486–3494.

Kaiwa N, Hosokawa T, Nikoh N, Tanahashi M, Moriyama M, Meng XY et al. (2014). Symbiont-supplemented maternal investment underpinning host's ecological adaptation. Curr Biol 24: 2465–2470.

Kaltenpoth M, Winter SA, Kleinhammer A . (2009). Localization and transmission route of Coriobacterium glomerans, the endosymbiont of pyrrhocorid bugs. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 69: 373–383.

Kaltenpoth M, Roeser-Mueller K, Koehler S, Peterson A, Nechitaylo TY, Stubblefield JW et al. (2014). Partner choice and fidelity stabilize coevolution in a Cretaceous-age defensive symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 6359–6364.

Kaltenpoth M, Steiger S . (2014). Unearthing carrion beetles' microbiome: characterization of bacterial and fungal hindgut communities across the Silphidae. Mol Ecol 23: 1251–1267.

Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T . (2007). Insect-microbe mutualism without vertical transmission: a stinkbug acquires a beneficial gut symbiont from the environment every generation. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 4308–4316.

Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Nikoh N, Meng X-Y, Kamagata Y, Fukatsu T . (2009). Host-symbiont co-speciation and reductive genome evolution in gut symbiotic bacteria of acanthosomatid stinkbugs. BMC Biol 7: 2.

Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T . (2011a). An ancient but promiscuous host-symbiont association between Burkholderia gut symbionts and their heteropteran hosts. ISME J 5: 446–460.

Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T . (2011b). Specific developmental window for establishment of an insect-microbe gut symbiosis. Appl Environ Microbiol 77: 4075–4081.

Koch H, Schmid-Hempel P . (2011). Bacterial communities in central European bumblebees: low diversity and high specificity. Microb Ecol 62: 121–133.

Kodrík D, Vinokurov K, Tomčala A, Socha R . (2012). The effect of adipokinetic hormone on midgut characteristics in Pyrrhocoris apterus L. (Heteroptera). J Insect Physiol 58: 194–204.

Koga R, Tsuchida T, Fukatsu T . (2003). Changing partners in an obligate symbiosis: a facultative endosymbiont can compensate for loss of the essential endosymbiont Buchnera in an aphid. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 270: 2543–2550.

Koga R, Bennett GM, Cryan JR, Moran NA . (2013). Evolutionary replacement of obligate symbionts in an ancient and diverse insect lineage. Environ Microbiol 15: 2073–2081.

Koga R, Moran NA . (2014). Swapping symbionts in spittlebugs: evolutionary replacement of a reduced genome symbiont. ISME J 8: 1237–1246.

Kohno K, Ngan BT, Fujiwara M . (2004). Predation of Dysdercus cingulatus (Heteroptera: Pyrrhocoridae) by the specialist predator Antilochus coqueberti (Heteroptera: Pyrrhocoridae). Appl Entomol Zool 39: 661–667.

Kristenová M, Exnerová A, Štys P . (2011). Seed preferences of Pyrrhocoris apterus (Heteroptera: Pyrrhocoridae): are there specialized trophic populations? Eur J Entomol 108: 581–586.

Kuechler SM, Renz P, Dettner K, Kehl S . (2012). Diversity of symbiotic organs and bacterial endosymbionts of lygaeoid bugs of the families Blissidae and Lygaeidae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Lygaeoidea). Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 2648–2659.

Lee C, Kim J, Shin SG, Hwang S . (2006). Absolute and relative QPCR quantification of plasmid copy number in Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol 123: 273–280.

Lee C, Lee S, Shin SG, Hwang S . (2008). Real-time PCR determination of rRNA gene copy number: Absolute and relative quantification assays with Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biot 78: 371–376.

Legendre P, Desdevises Y, Bazin E . (2002). A statistical test for host-parasite coevolution. Syst Biol 51: 217–234.

Li HM, Deng RQ, Wang JW, Chen ZY, Jia FL, Wang XZ . (2005). A preliminary phylogeny of the Pentatomomorpha (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) based on nuclear 18S rDNA and mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol 37: 313–326.

Li M, Tian Y, Zhao Y, Bu W . (2012). Higher level phylogeny and the first divergence time estimation of Heteroptera (Insecta: Hemiptera) based on multiple genes. PLoS One 7: e32152.

Lundgren JG, Lehman RM . (2010). Bacterial gut symbionts contribute to seed digestion in an omnivorous beetle. PLoS One 5: e10831.

Lynd LR, Weimer PJ, van Zyl WH, Pretorius IS . (2002). Microbial cellulose utilization: fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 66: 506–577.

Matsuura Y, Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Koga R, Meng XY, Kamagata Y et al. (2012). Evolution of symbiotic organs and endosymbionts in lygaeid stinkbugs. ISME J 6: 397–409.

Meehan CJ, Beiko RG . (2014). A phylogenomic view of ecological specialization in the Lachnospiraceae, a family of digestive tract-associated bacteria. Genome Biol Evol 6: 703–713.

Misof B, Liu S, Meusemann K, Peters RS, Donath A, Mayer C et al. (2014). Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science 346: 763–767.

Miyamoto S . (1961). Comparative morphology of alimentary organs of Heteroptera, with the phylogenetic consideration. Sieboldia Fukuoka 2: 197–259.

Moran NA, Tran P, Gerardo NM . (2005). Symbiosis and insect diversification: an ancient symbiont of sap-feeding insects from the bacterial phylum Bacteroidetes. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 8802–8810.

Moran NA . (2007). Symbiosis as an adaptive process and source of phenotypic complexity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 8627–8633.

Moran NA, McCutcheon JP, Nakabachi A . (2008). Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu Rev Genet 42: 165–190.

Muller HJ . (1956). Experimentelle studien an der symbiose von Coptosoma scutellatum Geoffr. (Hem. Heteropt.). Z Morphol Oekol Tiere 44: 459–482.

Page RDM. (1995). TreeMap for Windows version 3. Available from https://sites.google.com/site/cophylogeny/treemap.

Pinto-Tomas AA, Anderson MA, Suen G, Stevenson DM, Chu FS, Cleland WW et al. (2009). Symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the fungus gardens of leaf-cutter ants. Science 326: 1120–1123.

Podschun R, Ullmann U . (1998). Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev 11: 589–603.

Prado SS, Rubinoff D, Almeida RPP . (2006). Vertical transmission of a pentatomid caeca-associated symbiont. Ann Entomol Soc Am 99: 577–585.

Prado SS, Almeida RP . (2009). Phylogenetic placement of pentatomid stink bug gut symbionts. Curr Microbiol 58: 64–69.

Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP . (2010). FastTree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One 5: e9490.

Pruesse E, Peplies J, Glockner FO . (2012). SINA: accurate high-throughput multiple sequence alignment of ribosomal RNA genes. Bioinformatics 28: 1823–1829.

Rastogi SC . (1964). Studies on the digestive system of Odontopus nigricornis Stal (Hemiptera, Pyrrhocoridae). Tijdschr Ent 107: 265–275.

Salem H, Kreutzer E, Sudakaran S, Kaltenpoth M . (2013). Actinobacteria as essential symbionts in firebugs and cotton stainers (Hemiptera, Pyrrhocoridae). Environ Microbiol 15: 1956–1968.

Salem H, Bauer E, Strauss AS, Vogel H, Marz M, Kaltenpoth M . (2014). Vitamin supplementation by gut symbionts ensures metabolic homeostasis in an insect host. P Roy So B-Biol Sci 281: 20141838.

Salem H, Florez L, Gerardo N, Kaltenpoth M . (2015). An out-of-body experience: the extracellular dimension for the transmission of mutualistic bacteria in insects. P Roy So B-Biol Sci 282: 20142957.

Sanders JG, Powell S, Kronauer DJC, Vasconcelos HL, Frederickson ME, Pierce NE . (2014). Stability and phylogenetic correlation in gut microbiota: lessons from ants and apes. Mol Ecol 23: 1268–1283.

Saxena KN, Bhatnagar P . (1958). Physiological adaptations of dusky cotton bug, Oxycarenus hyalinipennis (Costa) (Heteroptera; Lygaeidae) to its host plant, cotton. Pt. I. Digestive enzymes in relation to tissue preference. Proc Natl Inst Sci India B Biol Sci 24: 245–257.

Schaefer CW . (1993). The Pentatomomorpha (Hemiptera, Heteroptera) - an annotated outline of its systematic history. Eur J Entomol 90: 105–122.

Schauer C, Thompson CL, Brune A . (2012). The bacterial community in the gut of the cockroach Shelfordella lateralis reflects the close evolutionary relatedness of cockroaches and termites. Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 2758–2767.

Schneider DL, Sheehan ET, Vavich MG, Kemmerer AR . (1968). Effect of Sterculia foetida oil on weanling rat growth and survival. J Agric Food Chem 16: 1022.

Schorr H . (1957). Zur verhaltensbiologie und symbiose von Brachypelta Aterrima först. (Cydnidae, Heteroptera). Zoomorphology 45: 561–602.

Schuh RT, Slater JA . (1995) True Bugs of the World (Hemiptera: Heteroptera): Classification and Natural History. Cornell University Press: : Ithaca, New York.

Scudder SH . (1890). The fossil insects of North America, with notes on some European species. 2. The tertiary insects. Rep US Geol Survey Territories 13: 1–734.

Silva CP, Terra WR . (1994). Digestive and absorptive sites along the midgut of the cotton seed sucker bug Dysdercus peruvianus (Hemiptera: Pyrrhocoridae). Insect Biochem Mol Biol 24: 493–505.

Simon C, Frati F, Beckenbach A, Crespi B, Liu H, Flook P . (1994). Evolution, weighting, and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial gene sequences and a compilation of conserved polymerase chain reaction primers. Ann Entomol Soc Am 87: 651–701.

Singh R, Singh PP . (2001). Studies of the anatomy and histology of the alimentary canal of Antilochus coqueberti (Heteroptera: Pyrrhocoridae) under fed and starved conditions. Himalayan J Environ Zool 15: 87–100.

Socha R . (1993). Pyrrhocoris apterus (Heteroptera) - an experimental model species: a review. Eur J Entomol 90: 241–286.

Stackebrandt E, Zeytun A, Lapidus A, Nolan M, Lucas S, Hammon N et al. (2013). Complete genome sequence of Coriobacterium glomerans type strain (PW2(T)) from the midgut of Pyrrhocoris apterus L. (red soldier bug). Stand Genomic Sci 8: 15–25.

Statz G, Wagner E . (1950). Geocorisae (Landwanzen) aus den oberoligoca'nen Ablagerungen von Rott. Palaeontographica 98A: 97–136.

Sudakaran S, Salem H, Kost C, Kaltenpoth M . (2012). Geographical and ecological stability of the symbiotic mid-gut microbiota in European firebugs, Pyrrhocoris apterus (Hemiptera, Pyrrhocoridae). Mol Ecol 21: 6134–6151.

Sun Y, Wolcott RD, Dowd SE . (2011). Tag-encoded FLX amplicon pyrosequencing for the elucidation of microbial and functional gene diversity in any environment. Methods Mol Biol 733: 129–141.

Tada A, Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Musolin DL, Fujisaki K, Fukatsu T . (2011). Obligate association with gut bacterial symbiont in Japanese populations of the southern green stinkbug Nezara viridula (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Appl Entomol Zool 46: 483–488.

Takiya DM, Tran PL, Dietrich CH, Moran NA . (2006). Co-cladogenesis spanning three phyla: leafhoppers (Insecta: Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) and their dual bacterial symbionts. Mol Ecol 15: 4175–4191.

Toju H, Tanabe AS, Notsu Y, Sota T, Fukatsu T . (2013). Diversification of endosymbiosis: replacements, co-speciation and promiscuity of bacteriocyte symbionts in weevils. ISME J 7: 1378–1390.

Urban JM, Cryan JR . (2012). Two ancient bacterial endosymbionts have coevolved with the planthoppers (Insecta: Hemiptera: Fulgoroidea). BMC Evol Biol 12: 87.

van Borm S, Buschinger A, Boomsma JJ, Billen J . (2002). Tetraponera ants have gut symbionts related to nitrogen-fixing root-nodule bacteria. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 269: 2023–2027.

Von Dohlen CD, Moran NA . (2000). Molecular data support a rapid radiation of aphids in the Cretaceous and multiple origins of host alternation. Biol J Linnean Soc 71: 689–717.

Wang H, Moore MJ, Soltis PS, Bell CD, Brockington SF, Alexandre R et al. (2009). Rosid radiation and the rapid rise of angiosperm-dominated forests. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 3853–3858.

Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR . (2007). Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 5261–5267.

Warnecke F, Luginbuhl P, Ivanova N, Ghassemian M, Richardson TH, Stege JT et al. (2007). Metagenomic and functional analysis of hindgut microbiota of a wood-feeding higher termite. Nature 450: 560–565.

Weisburg W, Barns S, Pelletier D, Lane D . (1991). 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol 173: 697–1400.

Wetschnig W, Depisch B . (1999). Pollination biology of Welwitschia mirabilis HOOK. f. (Welwitschiaceae, Gnetopsida). Phyton-Annales Rei Botanicae 39: 167–183.