Abstract

Little is known about the biogeography or stability of sediment-associated microbial community membership because these environments are biologically complex and generally difficult to sample. High-throughput-sequencing methods provide new opportunities to simultaneously genomically sample and track microbial community members across a large number of sampling sites or times, with higher taxonomic resolution than is associated with 16 S ribosomal RNA gene surveys, and without the disadvantages of primer bias and gene copy number uncertainty. We characterized a sediment community at 5 m depth in an aquifer adjacent to the Colorado River and tracked its most abundant 133 organisms across 36 different sediment and groundwater samples. We sampled sites separated by centimeters, meters and tens of meters, collected on seven occasions over 6 years. Analysis of 1.4 terabase pairs of DNA sequence showed that these 133 organisms were more consistently detected in saturated sediments than in samples from the vadose zone, from distant locations or from groundwater filtrates. Abundance profiles across aquifer locations and from different sampling times identified organism cohorts that comprised subsets of the 133 organisms that were consistently associated. The data suggest that cohorts are partly selected for by shared environmental adaptation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microbial biogeographic patterns describe the distribution, diversity and abundance of microorganisms within and across environments. They are influenced by a wide variety of microbially driven processes, including biogeochemical cycling (Wilms et al., 2006). Microorganisms have been shown to exhibit biogeography, that is, everything is not everywhere. Rather, the observed spatial and temporal community variations are based on both historical occurrences and environmental factors (Whitaker et al., 2003; Martiny et al., 2006). The rates of processes underlying biogeography are expected to vary more widely for microorganisms compared with larger organisms, with fewer reproductive and dispersal constraints related to body size (Martiny et al., 2006).

Sediments harbor a large fraction of the microbial life on earth (Paul, 2006; Kallmeyer et al., 2012). These large, contiguous regions sometimes exhibit high geochemical variability, making them important test cases for examinations of the impact of chemical environment on microbial biogeography. Subsurface sediments can be difficult and costly to access, limiting explorations of microbial diversity and causing many studies to rely solely on pumped groundwater as representative samples of the microbial community in a given aquifer. Early examinations of microbial biogeography using cell-staining methods identified consistent enrichment of microbial numbers in sediment fractions compared with groundwater from pristine and contaminated aquifers alike, often with orders of magnitude more cells detected in sediment samples (Harvey et al., 1984; Hazen et al., 1991; Holm et al., 1992; Alfreider et al., 1997). Later T-RFLP and 16 S ribosomal (RNA) gene clone library-based studies confirmed higher bacterial community density and, in addition, higher diversity of sediment communities compared with groundwater (Flynn et al., 2008, 2013). There is some evidence for a reverse trend for archaea, which exhibited higher abundance and diversity in groundwater compared with sediment in one study (Flynn et al., 2013). In studies that directly compared sediment and groundwater communities from the same site, a trend of no more than 30% overlap in the bacterial communities was determined (Reardon et al., 2004; Flynn et al., 2008, 2013). Gene surveys of 16 S rRNA provide, at best, species-level resolution, but most studies have focused on higher taxonomic levels, or, alternatively, tracked a few specific lineages of interest across samples (Reardon et al., 2004; Flynn et al., 2013; Longnecker & Kujawinski, 2013). As an example, Flynn et al. (2008) examined distributions of the metal-respiring microbes Geothrix and Geobacter, showing Geobacter sp. made up 20% of sediment communities, but <1% of the accompanying groundwater community. The remaining organisms cataloged through T-RFLP were not identified, but were useful for a general description of the community diversities and overlap. The trends in geographical distribution of specific organisms from sediment environments as well as how those distributions can be leveraged to infer biological interrelationships within communities remain open questions.

The field site at Rifle, CO borders the Colorado River, and is an unconfined aquifer system with low-level contamination by uranium and other heavy metals, a legacy of its time as a mining refinery site. The aquifer has been heavily studied from the perspective of fluid flow modeling, reactive transport of contaminants and microbial community response to acetate injection to stimulate bioremediation through uranium reduction (for example, Chang et al., 2005; Yabusaki et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009; Wilkins et al., 2009). Recent metagenomic characterization of the sediment and groundwater-associated communities identified diverse assemblages of low-abundance organisms, many of which represent previously unsequenced lineages on the tree of life (Wrighton et al., 2012; Castelle et al., 2013). The wealth of geochemical data and metagenomic sampling available from the Rifle site make it an excellent location for examining microbial community structure in sediment over space and time.

Here we conducted deep metagenomic sequencing of two new sediment cores and filtered groundwater from a site within the Rifle, CO aquifer. This, in combination with previously sequenced metagenomic data sets from locations 10–50 meters away, resulted in 36 data sets for spatial and temporal analysis. We identified the abundant organisms in a sample from below the water table, at 5 m depth, and tracked their abundances across the 36 data sets. We focused on this community to enable comparative analyses with the community present at 5 m depth at another site in the aquifer (Castelle et al., 2013; Hug et al., 2013). This approach allowed an investigation into the abundance and persistence of a given microbial community across vertical and lateral transects in the subsurface.

Materials and methods

CSP core and groundwater sampling

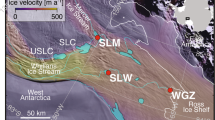

Two sediment cores were drilled at location FP-101 at the Rifle research site, adjacent to the Colorado River (Latitude 39.52927920, Longitude -107.77162320, altitude 1618.31 m above sea level). The first core was drilled on 20 July 2011 and the second on 28 March 2013, with the drill sites separated by ∼1 m. For both cores, sediment was sampled at depths 3, 4, 5 and 6 m below ground surface with all drilling-recovered sediments processed within N2-flushed glove bags for subsequent microbial analysis. Sediment was placed in gas-impermeable bags, stored at −80 °C and kept frozen for transport and storage before DNA extraction. For each depth, the frozen sediment was split into 2–4 pieces, generating replicate samples for extraction. Each sample comprised ∼100 g of sediment, extracted with 10 independent DNA extractions of ∼10 g of sediment. Extractions were conducted per sample using the PowerMax Soil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) with the following modifications to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sediment was vortexed at maximum speed for an additional 3 min in the sodium dodecyl sulphate reagent, and then incubated for 30 min at 60 °C, with intermittent shaking in place of extended bead beating. The 10 DNA extractions were concentrated using a sodium acetate/ethanol/glycogen precipitation and then pooled. A total of 24 sediment-associated pooled DNA samples were generated from the two cores (Figure 1).

Sample site locations. Top panel: map view. The CSP sampling sites fall within the yellow circle; prior metagenomic sampling sites are marked with green circles: (A) RBG site (Castelle et al., 2013; Hug et al., 2013, B) AAC site (Kantor et al., 2013, C) GW2011 site. Middle panel: sampling schematic for the sediment cores drilled and groundwater filtered from the CSP location; boxes indicate replicate samples. The CSP-I_5m_4 sample selected for assembly is outlined in bold. Bottom panel: sampling schematic for the previous metagenomic datasets. (A) RBG samples from three depths (Castelle et al., 2013; Hug et al., 2013). (B) AAC site: sediment incubated in a groundwater well prior to an acetate amendment experiment (Kantor et al., 2013; Handley et al., 2014). (C) GW2011 site: groundwater filtrate (‘A’) obtained prior to an acetate amendment experiment (Luef et al., 2015).

The groundwater monitoring well installed at FP-101 was used to collect the two large volume-filtered groundwater samples (GW_1 and GW_2). Approximately 36 000 l of groundwater was pumped from well FP-101 for each sampling event through serially connected polyethersulfone membrane filter cartridges having pore sizes of 1.2, 0.2 and 0.1 μm (Graver Technologies, Glasgow, DE, USA). Filtration of the two samples was completed on 3 June 2013 (GW_1; pump rate ca. 5 l h−1) and 7 July 2013 (GW_2; pump rate ca. 2.5 l h−1). To dislodge biomass from the filters, the 1.2, 0.2 and 0.1 μm filters were back-flushed (that is, reverse flow) with ∼3000 ml of distilled, deionized water containing 0.5% Tween 80, 0.01% Sodium Pyrophosphate and 0.001% Antifoam Y-30 emulsion (all reagents, Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA). The back-flushed solution from each filter size was collected into 250 ml centrifuge bottles, centrifuged at 15 300 g (10 000 r.p.m.), and the supernatant removed and biomass pooled and kept frozen at −80 °C for transport and storage prior to DNA extraction. DNA extractions were conducted as above for sediment samples with one-third of the back-flushed biomass added directly to the lysis step of the protocol. Each filter size was extracted independently, generating six DNA samples.

All of the samples from the FP-101 well, including sediment and groundwater, together comprise the Community Science Project (CSP) samples. Each of the 30 CSP DNA samples (Figure 1) was used to construct an Illumina sequencing library with a target insert size of 500 bp (using Sage Sciences Pippin Prep) and sequenced on a full lane of Illumina HiSeq 2000 using paired 150 bp reads.

Assembly and annotation of the CSP-I_5m_4 sample

Reads from the CSP-I_5m_4 sample were trimmed with Sickle (https://github.com/najoshi/sickle) using default settings. Paired-end reads were assembled using idba_ud under default settings (Peng et al., 2012). For scaffolds >5000 bp, open-reading frames were predicted with Prodigal (Hyatt et al., 2010) and functional predictions determined through similarity searches against the UniRef90 (Suzek et al., 2007) and KEGG (Ogata et al., 1999; Kanehisa et al., 2012) databases as described previously (Hug et al., 2013), but without the additional InterproScan search.

Identification and taxonomic placement of CSP-I_5m_4 abundant organisms

All scaffolds containing ribosomal proteins of interest (RpL2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 14, 15, 16, 18, 22, 24 and RpS3, 8, 10, 17, 19) were identified in the annotated CSP-I_5m_4 metagenome using similarity and keyword searches. Each scaffold was considered representative of a single taxon for further analyses. Individual ribosomal protein data sets were constructed, each containing a reference set of 997 bacterial and archaeal proteins from the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) and JGI-IMG (Joint Genome Institute Integrated Microbial Genomes) databases, the 160 organisms identified from the RBG_5m metagenome (RBG, Rifle BackGround; Castelle et al., 2013; Hug et al., 2013), and all CSP-I_5m_4 proteins with the correct annotation. Protein data sets were aligned using Muscle v. 3.8.31 (Edgar, 2004a, 2004b). Alignments were manually curated to remove end gaps and ambiguously aligned regions, then concatenated to form a 16-protein alignment. Taxa were filtered to exclude organisms represented by fewer than 8 of the 16 proteins, leaving a final alignment of 1319 organisms and 2304 positions. A maximum likelihood phylogeny was conducted using RAxML under the PROTGAMMALG model of evolution and with 100 bootstrap replicates (Stamatakis, 2006). CSP-I_5m_4 organisms were assigned a phylum based on bootstrap-supported phylogenetic affiliation with reference genomes.

Ribosomal protein S3 genes were used to compare the microbial communities in the RBG_5m and CSP-I_5m_4 samples, as a single copy marker gene representative of the syntenic ribosomal protein block described above. All rpS3 genes were identified from the CSP-I_5m_4, and reciprocally Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (Altschul et al., 1990) searched against all rpS3 genes identified from the previously published RBG_5m metagenome (Castelle et al., 2013). Matches were considered if they were reciprocal best-hits with a minimum alignment of 100 bp. Sequence similarity was calculated for each match based on both pair-wise alignments of the rpS3 genes, and a global alignment of the scaffolds encoding each rpS3 gene. Pairwise gene alignments were generated using Muscle (Edgar, 2004b, 2004a), and global scaffold alignments were conducted with Mauve (Darling et al., 2010).

Read mapping for heterogeneity examination

A total of 162 scaffolds containing a minimum of eight ribosomal proteins for taxonomic placement were identified from the CSP-I_5m_4 metagenome (Supplementary Figure S1). Full-length nucleotide reciprocal Basic Local Alignment Search Tool searches were conducted, and 56 scaffolds identified that share ⩾98% nucleotide identity with another scaffold or scaffolds across the length of the shorter scaffold (25 pairs and two sets of three). In each case, the longest scaffold was kept for the mapping analysis, making a final data set of 133 scaffolds. The ribosomal protein-encoding scaffolds were used as proxies for organism genomes for the abundance and heterogeneity analysis. Reads from each of the 36 metagenomes were mapped using Bowtie2 under default, paired-read parameters (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). Read matches were filtered to require ⩾98% identity for both paired reads (if both mapped) or for a given read (if only one of a pair mapped). Coverage was calculated for each scaffold for all 36 metagenomes, and all coverage values normalized by total number of high-quality reads in the data sets (Supplementary Table S1). Relationships among organisms or samples were examined using the normalized coverage values and the heatmap function in R (http://www.r-project.org). For the final visual product, coverage values were converted as follows: <1x=1, 1–10x=2, 10–35x=3, 35–50x=4 and 50x+=5. This allowed for better visual discrimination between lower abundance values, which constitute the majority of the data points.

Sequence availability information

All data sets utilized for read mapping are publicly available through the JGI portal and the IMG-M database, or through the NCBI SRA database (see Table 1 for project IDs/accessions). The ribosomal protein-encoding scaffolds from the 162 CSP-I_5m_4 organisms have been deposited in the NCBI database under Bioproject PRJNA262935 and Biosample SAMN03092877.

Results and discussion

We conducted deep metagenomic sequencing of sediment cores and filtered groundwater from sites within an aquifer adjacent to the Colorado River near Rifle, CO, USA. Recent work identified substantial microbial diversity in the aquifer’s saturated sediment and groundwater, including previously unsequenced phyla (Wrighton et al., 2012, 2014; Castelle et al., 2013; Kantor et al., 2013). For this study, sediment was sampled at 3, 4, 5 and 6 m below ground surface, with two to four replicates per depth, from two sediment cores drilled 20 months apart at sites separated by 1 m (CSP-I and CSP-II; Figure 1). Two groundwater samples were obtained via filtration through serial 1.2, 0.2 and 0.1 μM filters 3 months after the second core was drilled (CSP_GW_1 and CSP_GW_2). Six previously sequenced metagenomic data sets from locations 10–50 meters from the main site were also analyzed (AAC, GW2011 and RBG; Figure 1). The final set of 36 metagenomes from the aquifer comprised 1.4 terabase pairs of DNA sequencing (Table 1), and allowed investigation into the distribution of specific microbial community members across depth, space and time.

Given the previous extensive analysis of the RBG_5m sediment metagenome (Figure 1 site A; Castelle et al., 2013; Hug et al., 2013), we selected a metagenome from the 5 m depth of the CSP-I sediment core (CSP-I_5m_4) for assembly and annotation. Individual organisms were assigned taxonomy through phylogenetic analysis of concatenated ribosomal protein sequence alignments. The CSP-I_5m_4 sediment community was very diverse and no single organism comprised >1% of the total community, as was the case for the RBG_5m sample. The two samples contain similar proportions of Chloroflexi, Proteobacteria and other phyla (for example, Chloroflexi at 16 and 14%, Supplementary Figure S1, Hug et al., 2013). However, in a closer comparison of the communities, only 20 of the 162 CSP-1_5m_4 and 14 of the 160 RBG_5m most abundant organisms are predicted to have species-level relatives in the other sample, a total of 10.6% of the identified organisms. Species predictions were based on a prior analysis of ribosomal protein S3 (rpS3) divergence, which identified 98% and 90% nucleotide identities as thresholds for species and genera, respectively (Sharon et al., 2015). Expanding to genera, only an additional 10 organisms from the two data sets would be considered shared across the communities. The rpS3 identities tally closely with sequence identities between global alignments of scaffolds encoding the ribosomal protein block when identities are >90% (R2=0.82), meaning the rpS3 divergence is indicative of the average orthologous gene identity between relatively closely related genomes (Supplementary Table S2). The majority of organisms in the two communities were less closely related, with 64% of the organisms sharing <70% rpS3 nucleotide identity with any member of the other sample’s community, a threshold delineating family-level divergence or greater (Sharon et al., 2015). The two sites are separated by ∼50 meters and sampling occurred 4 years apart, so the community divergence may be a function of spatial and/or temporal separation, of altered geochemical conditions, or some combination of the three. Key geochemical differences between the two sites are the ferrous iron concentration (CSP-I=0.01 mg l-1, RBG=3.13 mg l-1) and the distribution of nitrogen species, with high nitrate and low ammonium at the CSP site compared with the inverse at the RBG site (Supplementary Table S3), both of which likely factor in the enrichment of different community members at the two sites.

Expanding our analysis to incorporate available metagenomic data, we tracked CSP-I_5m_4 organisms across 36 samples using scaffolds encoding syntenic blocks of single copy ribosomal proteins as proxies for genomes (Supplementary Figure S2). The 162 ribosomal protein scaffolds discussed above were clustered based on ⩾98% DNA identity, resulting in 133 organism populations. The standard for defining microbial species, in practice or as a theoretical concept, is a question of much contention (Konstantinidis et al., 2006; Achtman and Wagner, 2008). Although 16 S rRNA genes have typically been used to determine microbial taxonomy, the 16 S rRNA gene has insufficient genetic information to reliably define microbes into species (Achtman and Wagner, 2008). Species were originally defined from 70% DNA:DNA hybridization tests, which corresponds to ∼95% average nucleotide identity (ANI) (Konstantinidis et al., 2006; Achtman and Wagner, 2008). A more recent examination set the species definition threshold at 98.7% ID for 16 S rRNA genes (Yarza et al., 2014). Our method, relying on ANI across a contiguous stretch of syntenic, non-laterally transferred genes (Sorek et al., 2007; Wu and Eisen, 2008), is closer in nature to the original species definition and provides substantially more informative sites in an alignment for taxonomic placement (∼2300 amino-acid positions representing 6900 nucleotides vs ∼1500 nucleotides for full-length 16 S rRNA gene sequences). A recent study comparing the resolution and accuracy of a prokaryotic 16 S rRNA gene phylogeny, concatenated protein marker gene ‘supertrees’ and protein gene supermatrices concluded that the concatenated marker gene maximum likelihood approach should be the preferred method for phylogenetic placement (Lang et al., 2013). In addition, our ability to track organisms through a series of data sets with stringent read-mapping would be hampered by the universally highly conserved regions in the 16 S rRNA gene, whereas for ribosomal protein-encoding scaffolds, the level of divergence is more consistent across the full span of the sequence used. As for the selection of nucleotide identity to define taxonomic units tracked in this study, Konstantinidis et al. (2006) showed that strains could robustly be defined based on >98% ANI, with species thus bounded by 95–98% ANI, whereas our previous work identified 98% ANI as a species boundary (Sharon et al., 2015). Hence, we have clustered organisms at 98% global sequence identity as a conservative definition of species, and as a threshold allowing robust mapping of reads for abundance estimates. Read mapping was conducted with a requirement for 98% stringency (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) and, after normalization to account for dataset sizes, read depth was used to measure relative species abundance (Supplementary Table S1).

The replicate depth samples from both CSP-I and CSP-II-saturated sediments presented very similar abundance patterns for the 133 tracked organisms. This similarity was interesting given DNA was extracted from ∼100 g of sediment that contained no cobbles larger than ∼1 cm in diameter, a sample of ∼70 cm3. In fact, 129 of the 133 organisms were detected in all 19 saturated-sediment CSP samples, despite separation by one-meter distances and/or 20 months. These findings indicate that, at least for saturated sediments and at the tens of cm3 scale, community members can persist across meter distances, years and seasonal changes.

A previous study tracking nosZ gene divergence as a proxy for nitrifying bacteria surveying cm, m and km-scale microbial community diversity found the nosZ gene variability increased with distance, but that temporal variation could be as high as spatial variation at distances of ∼1 m (Scala and Kerkhof, 2000). In our analysis, temporal separation of 20 months and distance measures of 1 m both influence organism abundances (Figure 2). When clustered based on the 133 organisms’ abundances, the 4 and 5 m depth samples segregate by temporal sampling, whereas the 133 organisms in the 6 m depth samples are more consistent across time compared with shallower samples from either time point. The higher temporal stability of the tracked community in 6 m samples may be due to the deeper aquifer being less impacted by seasonal shifts in the water table and influx of carbon or other nutrients through seasonal run-off events. The segregation of the 4 and 5 m depths by sampling time points is likely thus more a function of both temporal separation and season of sampling rather than the 1 m lateral distance. That the abundance of many community members can remain stable across both 1 m vertical and horizontal transects, and across a span of almost 2 years is reassuring for future microbial biogeography surveys: for sediment environments, it is impossible to sample the precise site a second time owing to the disturbance to the matrix from the initial sampling. Our results suggest that, for this aquifer system at least, but possibly for a broader range of aquifer environments, samples separated by 1 m distances but encompassing similar topographical conditions (water table and so on) can function as replicates in terms of microbial communities, whereas seasonal or temporal variables may drive observed community abundance differences at that sampling scale.

Substantial heterogeneity exists in the subsurface across meter and tens of meter scales. The heat map for 36 metagenomic data sets (columns) is based on reads mapped to ribosomal protein-encoding scaffolds from the CSP-I_5m_4 assembly (rows). Higher depths of coverage correspond to darker blues. Sampling sites and organisms are ordered based on hierarchical clustering of the 133 organisms’ abundance patterns (trees). The phylum-level assignment of each species is designated by the colored squares, with phyla in the legend ordered from highest to lowest community abundance (CP=candidate phylum). Organisms classified as ‘bacteria’ were not affiliated with a currently named phylum. Sample names are colored by environment (same as in Figure 1). The final number in sample names refers to replicate number (sediment) or filter size in μM (groundwater). Red and purple nodes highlight cohorts discussed in the text.

The abundance patterns of the 133 CSP-I_5m_4 organisms separate samples from saturated vs unsaturated sediment and from groundwater (Figure 2). The RBG, AAC, CSP-I and -II vadose zone, GW2011 and CSP groundwater samples contain markedly lower abundances of the 133 organisms (Figure 2). This implies that the majority of the abundant organisms in these samples are not the dominant organisms in the CSP-I_5m_4 sediment. Some of the 133 organisms were not detected (zero reads mapped to ribosomal protein scaffolds), although which organisms were present or absent varied with environment type (Supplementary Table S1).

Groundwater samples have consistently shown lower microbial numbers compared with sediment-associated environments as well as low overlap (∼30%) in community composition (Hazen et al., 1991; Harvey et al., 1984; Holm et al., 1992; Alfreider et al., 1997; Flynn et al., 2008). The extent of overlap of the groundwater and sediment communities from the CSP site can be estimated from the number of sediment-associated organisms detected in the groundwater samples. Of the 133 organisms examined, only 34 were detected in either CSP_GW sample at coverage levels greater than 3x, the lowest coverage for which a ribosomal protein scaffold was assembled in the CSP-1_5m_4 sample. It is thus expected that there would be no more than 26% overlap in organisms between the communities identified in assembled metagenomic sequence from CSP sediment and groundwater samples. Looking strictly at read mapping-based detection, without a sequence assembly coverage threshold, 120 organisms of the 133 are present in at least one CSP groundwater sample (87 with coverage >0.1x). This suggests the actual community overlap is higher, but that these sediment-associated organisms are at much lower abundance in the planktonic communities, and may not be detected using metagenomic or other sequence-based methods. The low abundances of many of the tracked 133 organisms are striking given the differing scales of sample size: each sediment sample comprised ∼70 cm3 compared with the 36 000 l of groundwater filtered (∼144 m3 given a porosity of 0.25 for Rifle site sediment (Yabusaki et al., 2007)). The planktonic community sequenced thus represents the microbial membership from a much larger physical environment than the sediment cores.

Despite the large sample sizes, the two different groundwater sites exhibit spatial/temporal separation effects in regard to the presence and abundance of certain sediment-associated lineages. There are 13 CSP-I_5m_4 organisms undetected (no mapped reads) in the CSP_GW samples, including four Euryarchaeota, two Acidobacteria and two Chloroflexi, and one organism from each of the Gammaproteobacteria, Actinobacteria, CP Zixibacteria and Bacteroidetes, and one organism that could not be classified to an existing phylum. Each of these organisms are also absent in the GW2011 samples (11 of 13 not detected, 2 below threshold for assembly), and there are an additional 18 CSP_5m_4 organisms undetected from the GW2011 samples for a total of 32 absent organisms. Ten of the additional organisms absent from the GW_2011 samples belong to the radiations that are absent from the CSP groundwater samples, including Euryarchaeota (two), Acidobacteria (three), Actinobacteria (two) and Chloroflexi (three). The remaining eight belong to diverse radiations, including the Thaumarchaeota, Proteobacteria and the candidate phyla Microgenomates, PER and GAL15. The CSP-I and GW2011 sites were separated by ∼20 m but sampled within the same month (compared with 2 years later for the CSP_GW samples). This suggests that spatial separation may have greater impact on correlations between groundwater and sediment-associated communities than temporal separation, consistent with the above noted stability of sediment communities over time.

A previous heterogeneity survey found higher overlap for archaeal populations compared with bacteria when comparing sediment with groundwater, as well as a general trend of higher archaeal diversity in groundwater (Flynn et al., 2013). We do not see the same trend of high archaeal overlap in our data. Of the 17 archaea identified from the CSP-I_5m_4 sample, only the two putative nanoarchaea are present at >3x coverage in a groundwater sample, and then only in the GW2011 0.1 μM filter, whereas 13 of 17 are near-absent (<0.1x) or completely undetected in all groundwater filtrates (Supplementary Table S1). This makes the predicted community overlap for archaea substantially lower than that of bacteria for sediment-groundwater comparisons (2–4 of 17 archaea (11.7–23.5%) vs 32–83 of 116 (27.6–71.6%)). In line with previous studies, here we find that groundwater samples do not reflect the community membership of sediment communities, and hence cannot be used to define the organismal diversity or metabolic processes occurring in the subsurface.

Organisms with similar abundance patterns may comprise cohorts that share adaptations to specific geochemical conditions. For example, a cohort of organisms from the CSP-I_5m_4 samples clusters based on shared lower abundance in the CSP-II saturated sediment samples and the CSP-I 6 m depth samples (red node on organism cluster diagram, Figure 2). The cohort can be further subdivided into a group of organisms with higher abundance in the CSP-II 3 m samples, and a group with equally low abundance in those depth samples as for the rest of the CSP-II core. This cohort contains organisms affiliated with several different phyla, including Acidobacteria, Bacteroidetes/Ignavibacteria and various classes of Proteobacteria. The reason for these organisms’ drop in abundance in the CSP-II sediment core is unknown: it may be due to the shifts in the biochemistry of the site based on seasonal changes from July to March, including lower dissolved oxygen and Fe(II) later at the site (Supplementary Table S3). The organisms are consistently at low abundance in the 6 m depth samples, suggesting their presence in the 3, 4 and 5 m depths of the CSP-I sediment core may be due to microaerophilic lifestyles that are expected close to the water table (typically located 3–4 m below the surface). This lifestyle would be restricted in the deeper sediments.

An alternative explanation for why organisms exhibit similar patterns of distribution may relate to their association through syntrophic, symbiotic or parasitic relationships. Organisms at high abundance in groundwater samples from the CSP and GW2011 sites cluster by filter pore size, and hence, cell size (purple nodes, Figure 2). The small-celled candidate phyla organisms enriched on the 0.1 μM filters have restricted metabolisms, lacking many core metabolic and biosynthetic pathways (Wrighton et al., 2012; Luef et al., 2015). The members of these candidate phyla radiations are predicted to rely on their surrounding microbial community for nutrients, cofactors and other compounds, forming syntrophic or even obligate symbiotic relationships (Kantor et al., 2013). The larger-celled organisms abundant on the 0.2 and 1.2 μM ground-water filters thus represent potential hosts, co-occurring with their putative symbionts. The organisms sharing abundance patterns across diverse subsurface environments are interesting targets for investigation of host–symbiont relationships. Future analyses on these organisms’ genomes can leverage the coverage information across samples determined for the ribosomal protein encoding scaffolds to identify other genome fragments from the assembled metagenome (Albertsen et al., 2013; Sharon et al., 2013), allowing genome resolution, metabolic profiling and an examination of the shared characteristics or lifestyles underlying these microbial cohorts.

In an overview examination of microbial biogeography, distance effects based on historical separation were significant only for scales of tens of kilometers, whereas shorter distance differences in community composition were ascribed to environmental effects, despite the relatively high passive diffusion rates of microorganisms (Martiny et al., 2006). On this scale, then, the Rifle, CO aquifer represents a microcosm wherein everything might be expected to be everywhere, with environmental changes driving the diversity observed. We examined the persistence and abundance of a microbial community across the aquifer, and found that for saturated sediments, community members’ abundances are stable at the centimeter and meter scales, across locations with similar geochemical conditions. The community abundances observed for depth sample replicates separated by 20 months indicate that temporal and seasonal effects have a stronger influence on community member persistence than a distance of 1 m. Temporal separation of 4 years with spatial separation of ∼50 m resulted in only 10% overlap between microbial communities at the species level. The substantial differences between the organism abundances from vadose and saturated zones, as well as between sediment-associated and planktonic communities, have implications for design of studies that aim to extend species-resolved microbial investigations to the catchment- and watershed-scales. Some organisms consistently associate with each other, probably because cohorts are selected for by environmental conditions or arise due to organismal interdependence. The use of ribosomal protein-encoding scaffolds as proxies for organism genomes allows definition of species-level groups, robust read-mapping for abundance estimates, and ultimately, the ability to link the microbial biogeographical patterns to metagenome-derived genomes for metabolic prediction.

References

Achtman M, Wagner M . (2008). Microbial diversity and the genetic nature of microbial species. Nat Rev Microbiol 6: 431–440.

Albertsen M, Hugenholtz P, Skarshewski A, Nielsen KL, Tyson GW, Nielsen PH . (2013). Genome sequences of rare, uncultured bacteria obtained by differential coverage binning of multiple metagenomes. Nat Biotechnol 31: 533–538.

Alfreider A, Krössbacher M, Psenner R . (1997). Groundwater samples do not reflect bacterial densities and activity in subsurface systems. Water Res 31: 832–840.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ . (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215: 403–410.

Castelle CJ, Hug LA, Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Williams KH, Wu D et al. (2013). Extraordinary phylogenetic diversity and metabolic versatility in aquifer sediment. Nat Commun 4: 2120.

Chang Y-J, Long PE, Geyer R, Peacock AD, Resch CT, Sublette K et al. (2005). Microbial incorporation of 13C-labeled acetate at the field scale: detection of microbes responsible for reduction of U(VI). Environ Sci Technol 39: 9039–9048.

Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT . (2010). progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One 5: e11147.

Edgar RC . (2004a). MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5: 113.

Edgar RC . (2004b). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1792–1797.

Flynn TM, Sanford RA, Bethke CM . (2008). Attached and suspended microbial communities in a pristine confined aquifer. Water Resour Res 44: W07425.

Flynn TM, Sanford RA, Ryu H, Bethke CM, Levine AD, Ashbolt NJ et al. (2013). Functional microbial diversity explains groundwater chemistry in a pristine aquifer. BMC Microbiol 13: 146.

Handley KM, Wrighton KC, Miller CS, Wilkins MJ, Kantor RS, Thomas BC et al. (2014). Disturbed subsurface microbial communities follow equivalent trajectories despite different structural starting points. Environ Microbiol Online ahead of print.

Harvey RW, Smith RL, George L . (1984). Effect of organic contamination upon microbial distributions and heterotrophic uptake in a Cape Cod, Mass., aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol 48: 1197–1202.

Hazen TC, Jiménez L, López de Victoria G, Fliermans CB . (1991). Comparison of bacteria from deep subsurface sediment and adjacent groundwater. Microb Ecol 22: 293–304.

Holm PE, Nielsen PH, Albrechtsen HJ, Christensen TH . (1992). Importance of unattached bacteria and bacteria attached to sediment in determining potentials for degradation of xenobiotic organic contaminants in an aerobic aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol 58: 3020–3026.

Hug LA, Castelle CJ, Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Frischkorn KR et al. (2013). Community genomic analyses constrain the distribution of metabolic traits across the Chloroflexi phylum and indicate roles in sediment carbon cycling. Microbiome 1: 22.

Hyatt D, Chen G-L, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ . (2010). Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11: 119.

Kallmeyer J, Pockalny R, Adhikari RR, Smith DC, D’Hondt S . (2012). Global distribution of microbial abundance and biomass in subseafloor sediment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 16213–16216.

Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Tanabe M . (2012). KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res 40: D109–D114.

Kantor RS, Wrighton KC, Handley KM, Sharon I, Hug LA, Castelle CJ et al. (2013). Small genomes and sparse metabolisms of sediment-associated bacteria from four candidate phyla. MBio 4: e00708–e00713.

Konstantinidis KT, Ramette A, Tiedje JM . (2006). The bacterial species definition in the genomic era. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 361: 1929–1940.

Lang JM, Darling AE, Eisen JA . (2013). Phylogeny of bacterial and archaeal genomes using conserved genes: supertrees and supermatrices. PLoS One 8: e62510.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL . (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9: 357–359.

Li L, Steefel CI, Williams KH, Wilkins MJ, Hubbard SS . (2009). Mineral transformation and biomass accumulation associated with uranium bioremediation at Rifle, Colorado. Environ Sci Technol 43: 5429–5435.

Longnecker K, Kujawinski EB . (2013). Using stable isotope probing to characterize differences between free-living and sediment-associated microorganisms in the subsurface. Geomicrobiol J 30: 362–370.

Luef B, Frischkorn KR, Wrighton KC, Holman HY, Birarda G, Thomas BC et al. (2015). Diverse uncultivated ultra-small bacterial cells in groundwater. Nat Commun (in press).

Martiny JBH, Bohannan BJM, Brown JH, Colwell RK, Fuhrman JA, Green JL et al. (2006). Microbial biogeography: putting microorganisms on the map. Nat Rev Microbiol 4: 102–112.

Ogata H, Goto S, Sato K, Fujibuchi W, Bono H, Kanehisa M . (1999). KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 27: 29–34.

Paul EA . (2006) Soil Microbiology Ecology and Biochemistry. Academic Press: Oxford, UK.

Peng Y, Leung HCM, Yiu SM, Chin FYL . (2012). IDBA-UD: a de novo assembler for single-cell and metagenomic sequencing data with highly uneven depth. Bioinformatics 28: 1420–1428.

Reardon CL, Cummings DE, Petzke LM, Kinsall BL, Watson DB, Peyton BM et al. (2004). Composition and diversity of microbial communities recovered from surrogate minerals incubated in an acidic uranium-contaminated aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 6037–6046.

Scala DJ, Kerkhof LJ . (2000). Horizontal heterogeneity of denitrifying bacterial communities in marine sediments by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 1980–1986.

Sharon I, Kertesz M, Hug LA, Pushkarev D, Blauwkamp T, Castelle CJ et al. (2015). Multi-kb Illumina reads resolve complex populations and detect rare microorganisms. Genome Res (in press).

Sharon I, Morowitz MJ, Thomas BC, Costello EK, Relman DA, Banfield JF . (2013). Time series community genomics analysis reveals rapid shifts in bacterial species, strains, and phage during infant gut colonization. Genome Res 23: 111–120.

Sorek R, Zhu Y, Creevey CJ, Francino MP, Bork P, Rubin EM . (2007). Genome-wide experimental determination of barriers to horizontal gene transfer. Science 318: 1449–1452.

Stamatakis A . (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22: 2688–2690.

Suzek BE, Huang H, McGarvey P, Mazumder R, Wu CH . (2007). UniRef: comprehensive and non-redundant UniProt reference clusters. Bioinformatics 23: 1282–1288.

Whitaker RJ, Grogan DW, Taylor JW . (2003). Geographic barriers isolate endemic populations of hyperthermophilic archaea. Science 301: 976–978.

Wilkins MJ, Verberkmoes NC, Williams KH, Callister SJ, Mouser PJ, Elifantz H et al. (2009). Proteogenomic monitoring of Geobacter physiology during stimulated uranium bioremediation. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 6591–6599.

Wilms R, Sass H, Köpke B, Köster J, Cypionka H, Engelen B . (2006). Specific bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic communities in tidal-flat sediments along a vertical profile of several meters. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 2756–2764.

Wrighton KC, Castelle CJ, Wilkins MJ, Hug LA, Sharon I, Thomas BC et al. (2014). Metabolic interdependencies between phylogenetically novel fermenters and respiratory organisms in an unconfined aquifer. ISME J 8: 1452–1463.

Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Miller CS, Castelle CJ, VerBerkmoes NC et al. (2012). Fermentation, hydrogen, and sulfur metabolism in multiple uncultivated bacterial phyla. Science 337: 1661–1665.

Wu M, Eisen JA . (2008). A simple, fast, and accurate method of phylogenomic inference. Genome Biol 9: R151.

Yabusaki SB, Fang Y, Long PE, Resch CT, Peacock AD, Komlos J et al. (2007). Uranium removal from groundwater via in situ biostimulation: Field-scale modeling of transport and biological processes. J Contam Hydrol 93: 216–235.

Yarza P, Yilmaz P, Pruesse E, Glöckner FO, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H et al. (2014). Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16 S rRNA gene sequences. Nat Rev Microbiol 12: 635–645.

Acknowledgements

Metagenome sequence was generated at the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, via the Community Sequencing Program. Research was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under Award Number DE-AC02-05CH11231 (Sustainable Systems Scientific Focus Area and DOE-JGI) and Award Number DE-SC0004918 (Systems Biology Knowledge Base Focus Area). LAH was partially supported by an NSERC Post-Doctoral Fellowship. We would like to thank Tijana Glavina del Rio and Shweta Deshpande for assistance with the sequencing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hug, L., Thomas, B., Brown, C. et al. Aquifer environment selects for microbial species cohorts in sediment and groundwater. ISME J 9, 1846–1856 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.2

This article is cited by

-

Phylogenetic divergence and adaptation of Nitrososphaeria across lake depths and freshwater ecosystems

The ISME Journal (2022)

-

Spatial variation in bacterial community and dissolved organic matter composition in groundwater near a eutrophic lake

Aquatic Ecology (2022)

-

Distribution of ETBE-degrading microorganisms and functional capability in groundwater, and implications for characterising aquifer ETBE biodegradation potential

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2022)

-

Genomic reconstruction of fossil and living microorganisms in ancient Siberian permafrost

Microbiome (2021)

-

Ecological assessment of groundwater ecosystems disturbed by recharge systems using organic matter quality, biofilm characteristics, and bacterial diversity

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2020)